Abstract

Recent model-based phylogenetic approaches have expanded upon the incorporation of extinct lineages and their respective temporal information for calibrating divergence date estimates. Here, model-based methods are explored to estimate divergence dates and ancestral ranges for titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs, an extinct and globally distributed terrestrial clade that existed during the extensive Cretaceous supercontinental break-up. Our models estimate an Early Cretaceous (approx. 135 Ma) South American origin for Titanosauria. The estimated divergence dates are broadly congruent with Cretaceous geophysical models of supercontinental separation and subsequent continental isolation while obviating the invocation of continuous Late Cretaceous continental connections (e.g. ephemeral land bridges). Divergence dates for mid-Cretaceous African and South American sister lineages support semi-isolated subequatorial African faunas in concordance with the gradual northward separation between South America and Africa. Finally, Late Cretaceous Africa may have linked Laurasian lineages with their sister South American lineages, though the current Late Cretaceous African terrestrial fossil record remains meagre.

Keywords: Titanosauria, palaeobiogeography, phylogenetics, Gondwana

1. Introduction

The fossil record provides us a critical context for evolutionary biology; yet, it is notoriously incomplete and riddled with uncertainty. Model-based phylogenetic approaches offer us an explicit framework for addressing uncertainty as well as a likelihood model for morphological character evolution [1–4]. Recent studies [2–5] have incorporated morphological and temporal data (tip-dates) from both modern taxa and fossil specimens in order to co-estimate both phylogenetic relationships and divergence dates under an assumed ‘morphological clock’ that is analogous to a molecular clock. Here, this approach is applied to titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs. Titanosaurians were a globally distributed clade of Cretaceous large-bodied terrestrial herbivores with a partially resolved phylogeny and an obscure origin near the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary based on a deficit of unambiguous fossil specimens [6–11]. Model-based methods are implemented to take advantage of the worldwide distribution of titanosaurians for assessing the influence of Cretaceous supercontinental break-up and its reorganizational impact on the diversification of terrestrial biotas [12–18].

2. Methods

The dataset herein integrates several previous studies and includes autapomorphic characters for estimating terminal branch lengths (45 taxa, 262 variable and 230 autapomorphic characters; see the electronic supplementary material, appendix; [1]). The reported stratigraphic range for each taxon was sampled using a uniform distribution prior (see appendix; [3,5]). Morphology models [1] differed in either equal or variable rates of character evolution within beast v. 2.1.3 [19] and MrBayes v. 3.2 [20]. The beast analyses implemented the birth–death–skyline–serial–sampling tree model, allowing birth and death rates to vary through time [21], under a lognormal relaxed clock model. MrBayes v. 3.2 cannot currently use birth–death models with non-contemporaneous termini; thus, a uniform clock model with the independent gamma rate option drawn from an exponential distribution was implemented [5,20]. All four models ran for 20 million generations, sampling every 1000 generations with a standard 25% burn-in. Models were compared using the Bayes factor [22]. Palaeobiogeographic models DEC [23], the likelihood-interpretations of both DIVA [24] and BayArea [25] and alternative models including long-range dispersal parameter ‘+j’ within the R package BioGeoBEARS [26,27] were used with the best-fit phylogenetic model to reconstruct ancestral ranges.

3. Results

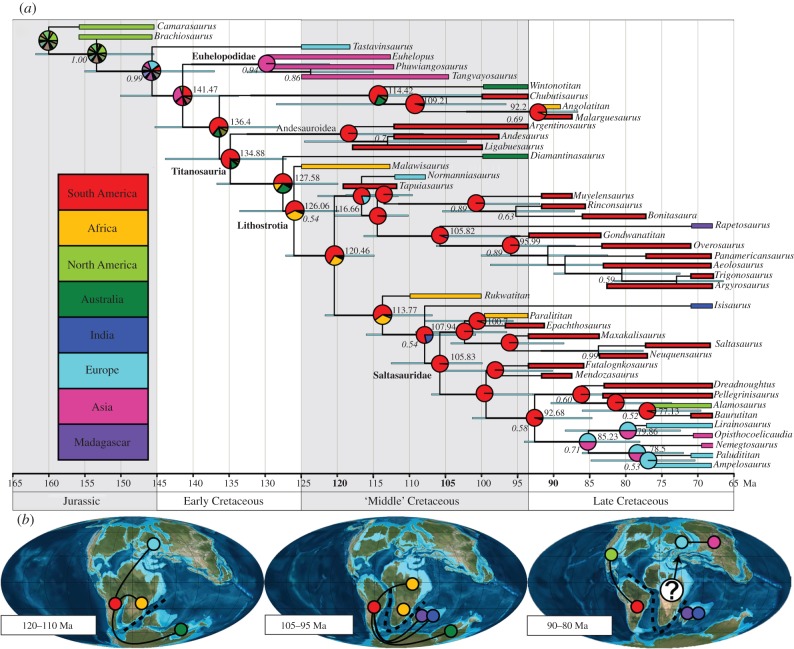

The beast variable-rates model is strongly supported over other models (figure 1 and table 1) and differences among the models include the position of several unstable taxa, orderings within subclades and estimated topological parameters (see appendix). The topology is broadly congruent with recent titanosaurian phylogenies [29,30]. DEC + j is the slightly favoured palaeobiogeographic model (table 1), suggesting occasional dispersal episodes as a factor. Alternatively, the ‘+j’ models may reflect uneven spatial and temporal sampling as distributional ranges are likely incomplete; the majority of established titanosaurian taxa are known exclusively from Mid–Late Cretaceous South American deposits [31].

Figure 1.

beast variable-rates and DEC+j model results for titanosaurian interrelationships and biogeographic reconstruction. (a) Select divergence dates (bold) and posterior probabilities (>50%, italics) located at respective nodes; blue nodal bar represents 95% highest posterior density (HPD) age estimates; pie charts indicate relative support for ancestral area reconstruction; branch tips represent the taxon 95% HPD age range (length) and area distribution (colour). (b) Cretaceous titanosaurian palaeogeographic reconstructions hypothesizing the development for both subequatorial African and global faunas [28].

Table 1.

Model log-likelihood (lnl) scores with Akaike information criterion (AIC) scores for BioGeoBEARS models.

| program | character model | tree model | clock model | lnl | Bayes factor | posterior probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| phylogenetic analyses | ||||||

| beast 2.1.3 | gamma | Skyline BDSS | relaxed; lognormal | −3781.12 | — | >0.99 |

| MrBayes 3.2 | gamma | height prior | relaxed; IGR | −3837.67 | 113.092 | <0.01 |

| beast 2.1.3 | equal | Skyline BDSS | relaxed; lognormal | −3866.12 | 170.008 | <0.01 |

| MrBayes 3.2 | equal | height prior | relaxed; IGR | −3883.17 | 204.094 | <0.01 |

| model | lnl | AIC | ΔAIC | d.f. | D-statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| palaeobiogeographic analyses from BioGeoBEARS | ||||||

| DEC | −89.61 | 183.2 | — | 2 | — | — |

| DEC + j | −65.99 | 138 | 45.2 | 3 | 47.23 | 6.30 × 10−12 |

| DIVALIKE | −86.86 | 177.7 | — | 2 | — | — |

| DIVALIKE + j | −66.42 | 138.9 | 38.8 | 3 | 40.88 | 1.60 × 10−10 |

| BAYAREALIKE | −109.29 | 222.6 | — | 2 | — | — |

| BAYAREALIKE + j | −67.76 | 141.5 | 81.1 | 3 | 83.05 | 8.00 × 10−20 |

4. Discussion

(a). Early Cretaceous (Berriasian–Barremian)

A titanosaurian origin is estimated at 134.88 million years ago (Ma; 95% highest posterior density: 143.88–127.12 Ma) and is compatible with the earliest unambiguous titanosaurian fossils that are known from the Barremian (130–125 Ma; [10,11]). Titanosauria is likely to have a Gondwanan origination in South America; however, the worldwide lack of an earliest Cretaceous (Berriasian–Barremian, approx. 145–125 Ma) titanosauriform fossil record renders our understanding of the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition incomplete, though increased sampling efforts targeting this interval will certainly assist with better characterization of palaeobiogeographic patterns.

(b). Mid-Cretaceous (Aptian–Cenomanian)

Recovered divergence dates for South American and African titanosaurian sister lineages follow the gradual northward ‘unzipping’ of these two continents and may have promoted the semi-isolation of subequatorial African faunas [32,33] prior to final separation (approx. 100 Ma; [34–38]). Subequatorial African titanosaurians are estimated to have diverged from their respective South American sister lineages earlier than the representative supra-equatorial African lineage, Paralititan. Within the aeolosaur lineage (here, taxa more closely related to Aeolosaurus than Saltasaurus), the predominately South American clade includes early-branching Malagasy and European lineages, suggesting a more widespread distribution than previously considered. Rapetosaurus (Madagascar) and Isisaurus (India) lineages are estimated to have diverged from their respective South American sister lineages around 105 and 108 Ma, respectively, which generally corresponds to the isolation of Indo-Madagascar [15,37,39]. Overall, most Late Cretaceous titanosaurian lineages likely originated earlier within the mid-Cretaceous.

(c). Late Cretaceous (Turonian–Maastrichtian)

Post-Cenomanian titanosaurian lineages support regionally isolated faunas [35,36] with a dispersal episode into North America from South America (Alamosaurus lineage). An ancestral supra-equatorial African stock may have bridged the recovered Eurasian clade with lineages from South America; however, Late Cretaceous African faunas remain poorly known [40,41]. Additional mid- and Late Cretaceous African fossils are required to rigorously evaluate and expand upon current palaeobiogeographic models (e.g. reticulated faunal associations). The estimated branch lengths obviate the invocation of ephemeral Late Cretaceous land bridges or other ad hoc explanations that have been proposed for other terrestrial taxa (e.g. theropod dinosaurs [42]).

5. Conclusion

Stratigraphically calibrated topologies via ad hoc minimal distances or arbitrary branch lengths may lead to overestimates of continuous continental connectivity when it may not have existed [13,15,34]. Co-estimating divergence dates and phylogenetic relationships facilitates direct comparisons between phylogenetic branching patterns and geophysical models of landmass separation. The models herein suggest that titanosaurians had attained a near-global distribution prior to the isolation of the continents with limited dispersals rather than invoke poorly constrained and chronic Late Cretaceous global connections [34,35,42,43]. The study of palaeobiogeographic patterns may not be as straightforward as previously thought, but instead these patterns are likely to be more variable depending on the clade under examination [16–18,34,35,42,43]. In summary, our models estimate that the global distribution of titanosaurians, and the regionalization of their constituent subclades predominantly follow geophysical patterns of continental separation and isolation throughout the Cretaceous.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Specimen access: E. Gomani, J. Banda and J. Chilachila (Malawi Department of Antiquities); K. Lacovara and P. Ullman (Drexel University); M. Carrano and A. Millhouse (National Museum of Natural History). A. Wright, N. Matzke and G. Lloyd for organizing ‘Putting Fossils in Trees’ symposium. Two anonymous reviewers provided invaluable perspectives on an earlier draft.

Data accessibility

Data available as electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

E.G. conceived the study, collected data, conducted analyses, and drafted the manuscript. P.M.O. coordinated the study, and helped draft the manuscript. Both authors are accountable and approve publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

E.G. was supported by Jurassic Foundation, Paleontological Society, Ohio University Student Enhancement Award and Original Work Grant. Both authors were supported by National Science Foundation, EAR_1349825.

References

- 1.Lewis PO. 2001. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 50, 913–925. ( 10.1080/106351501753462876) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pyron RA. 2011. Divergence time estimation using fossils as terminal taxa and the origins of Lissamphibia. Syst. Biol. 60, 466–481. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syr047) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronquist F, Klopfstein S, Vilhelmsen L, Schulmeister S, Murray DL, Rasnitsyn AP. 2012. A total-evidence approach to dating with fossils, applied to the early radiation of the Hymenoptera. Syst. Biol. 61, 973–999. ( 10.1093/sysbio/sys058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood HM, Matzke NJ, Gillespie RG, Griswold CE. 2013. Treating fossils as terminal taxa in divergence time estimation reveals ancient vicariance patterns in the palpimanoid spiders. Syst. Biol. 62, 264–284. ( 10.1093/sysbio/sys092) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MSY, Cau A, Naish D, Dyke GJ. 2014. Morphological clocks in paleontology, and a mid-Cretaceous origin of crown Aves. Syst. Biol. 63, 442–449. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syt110) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett PM, Upchurch P. 2005. Sauropodomorph diversity through time. In The sauropods: evolution and paleobiology (eds Curry Rogers K, Wilson J), pp. 125–156. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curry Rogers K, Wilson JA. 2005. Titanosauria: phylogenetic overview. In The sauropods: evolution and paleobiology (eds Curry K Rogers, Wilson J), pp. 50–103. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson JA. 2006. An overview of titanosaur evolution and phylogeny. In Actas de las III jornadas sobre dinosaurios y su entorno burgos [Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on the Paleontology of Dinosaurs and their Environment], pp. 169–190. Salas de los Infantes, Spain: Colectivo Arqueológico-Paleontológico de Salas. [In Spanish.] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salgado L, Coria RA, Calvo JO. 1997. Evolution of titanosaurid sauropods: phylogenetic analysis based on the postcranial evidence. Ameghiniana 34, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Emic MD. 2012. The early evolution of titanosauriform sauropod dinosaurs. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 166, 624–671. ( 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00853.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannion PD, Upchurch P, Barnes RN, Mateus O. 2013. Osteology of the Late Jurassic Portuguese sauropod dinosaur Lusotitan atalaiensis (Macronaria) and the evolutionary history of basal titanosauriforms. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 168, 98–206. ( 10.1111/zoj.12029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster C. 1999. Gondwanan dinosaur evolution and biogeographic analysis. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 28, 169–185. ( 10.1016/S0899-5362(99)00023-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sereno PC. 1999. The evolution of dinosaurs. Science 284, 2137–2147. ( 10.1126/science.284.5423.2137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upchurch P. 2008. Gondwanan break-up: legacies of a lost world? Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 229–236. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2007.11.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali JR, Krause DW. 2011. Late Cretaceous bioconnections between Indo-Madagascar and Antarctica: refutation of the Gunnerus Ridge causeway hypothesis. J. Biogeogr. 38, 1855–1872. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02546.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mannion PD, Upchurch P. 2011. A re-evaluation of the mid-Cretaceous sauropod hiatus and the impact of uneven sampling of the fossil record on patterns of regional dinosaur extinction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 299, 529–540. ( 10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.12.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fanti F. 2012. Cretaceous continental bridges, insularity, and vicariance in the southern hemisphere: which route did dinosaurs take? In Earth and Life: global diversity, extinction intervals and biogeographic perturbations through time (ed. Talent JA.), pp. 883–911. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upchurch P, Hunn CA, Norman DB. 2002. An analysis of dinosaurian biogeography: evidence for the existence of vicariance and dispersal patterns caused by geological events. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 613–621. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1921) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, Wu C-H, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. 2014. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003537 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronquist F, et al. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. ( 10.1093/sysbio/sys029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stadler T, Kühnert D, Bonhoeffer S, Drummond AJ. 2013. Birth–death skyline plot reveals temporal changes of epidemic spread in HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 228–233. ( 10.1073/pnas.1207965110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kass RE, Raftery AE. 1995. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 773–795. ( 10.1080/01621459.1995.10476572) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ree RH, Smith SA. 2008. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst. Biol. 57, 4–14. ( 10.1080/10635150701883881) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronquist F. 1997. Dispersal-vicariance analysis: a new approach to the quantification of historical biogeography. Syst. Biol. 46, 195–203. ( 10.1093/sysbio/46.1.195) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landis MJ, Matzke NJ, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP. 2013. Bayesian analysis of biogeography when the number of areas is large. Syst. Biol. 62, 789–804. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syt040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matzke NJ. 2014. Model selection in historical biogeography reveals that founder-event speciation is a crucial process in island clades. Syst. Biol. 63, 951–970. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syu056) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matzke NJ. 2013. Probabilistic historical biogeography: new models for founder-event speciation, imperfect detection, and fossils allow improved accuracy and model-testing. Front. Biogeogr. 5, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blakey RC. 2006. Global paleogeographic views of earth history–late Precambrian to recent. See http://cpgeosystems.com/index.html (accessed 9/1/15).

- 29.Santucci RM, De Arruda-Campos AC. 2011. A new sauropod (Macronaria, Titanosauria) from the Adamantina Formation, Bauru Group, Upper Cretaceous of Brazil and the phylogenetic relationships of Aeolosaurini. Zootaxa 3085, 1–33. ( 10.11646/%x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salgado L, Gallina P, Carabajal A. 2015. Redescription of Bonatitan reigi (Sauropoda: Titanosauria), from the Campanian–Maastrichtian of the Río Negro Province (Argentina). Hist. Biol. 27, 525–548. ( 10.1080/08912963.2014.894038) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner AH, Smith ND, Callery JA, Ebach M. 2009. Gauging the effects of sampling failure in biogeographical analysis. J. Biogeogr. 36, 612–625. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02020.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorscak E, O'Connor PM, Stevens NJ, Roberts EM. 2014. The basal titanosaurian Rukwatitan bisepultus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the middle Cretaceous Galula Formation, Rukwa Rift Basin, southwestern Tanzania. J. Vert. Paleontol. 34, 1133–1154. ( 10.1080/02724634.2014.845568) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connor PM, Gottfried M, Stevens N, Roberts E, Ngasala S, Kapilima S. 2006. A new vertebrate fauna from the Cretaceous Red Sandstone Group, Rukwa Rift Basin, Southwestern Tanzania. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 44, 277–288. ( 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.11.022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krause DW, O'Connor PM, Rogers KC, Sampson SD, Buckley GA, Rogers RR. 2006. Late Cretaceous terrestrial vertebrates from Madagascar: implications for Latin American biogeography. Ann. Mol. Bot. Gard. 93, 178–208. ( 10.3417/0026-6493(2006)93[178:LCTVFM]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sereno PC, Brusatte SL. 2008. Basal abelisaurid and carcharodontosaurid theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation of Niger. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 53, 15–46. ( 10.4202/app.2008.0102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezcurra MD, Agnolin FL. 2012. A new global palaeobiogeographical model for the Late Mesozoic and Early Tertiary. Syst. Biol. 61, 553–566. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syr115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seton M, et al. 2012. Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200 Ma. Earth-Sci. Rev. 113, 212–270. ( 10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.03.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heine C, Zoethout J, Müller RD. 2013. Kinematics of the South Atlantic rift. Solid Earth 42, 15–53. ( 10.5194/se-4-215-2013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaina C, Müller RD, Brown B, Ishihara T, Ivanov S. 2007. Breakup and early seafloor spreading between India and Antarctica. Geophys. J. Int. 170, 151–169. ( 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03450.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Connor PM, Sertich JJW, Manthi FK. 2011. A pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Lapurr sandstone, West Turkana, Kenya. Ann. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 83, 309–315. ( 10.1590/S0001-37652011000100019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mannion PD, Barrett PM. 2013. Additions to the sauropod dinosaur fauna of the Cenomanian (early Late Cretaceous) Kem Kem beds of Morocco: palaeobiogeographical implications of the mid-Cretaceous African sauropod fossil record. Cretaceous Res. 45, 49–59. ( 10.1016/j.cretres.2013.07.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sampson SD, Witmer LM, Forster CA, Krause DW, O'Connor PM, Dodson P, Ravoavy F. 1998. Predatory dinosaur remains from Madagascar: implications for the Cretaceous biogeography of Gondwana. Science 280, 1048–1051. ( 10.1126/science.280.5366.1048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sereno PC, Wilson JA, Conrad JL. 2004. New dinosaurs link southern landmasses in the Mid-Cretaceous. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 1325–1330. ( 10.1098/rspb.2004.2692) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available as electronic supplementary material.