Case Report

A wheelchair-dependent 12-year-old girl with underlying ataxia telangiectasia (A-T) presented with a 1-month history of headache and decline in mobility and was diagnosed with a malignant glioneuronal tumor of the right parietal lobe. A-T was confirmed by genetic testing when the girl was 7 years old. Laboratory testing showed increased chromosomal breakage after in vitro exposure to irradiation (3.02 chromatid abnormalities per cell; normal, 0.06 to 0.4 chromatid abnormalities per cell) and two deleterious sequence variations in the ATM gene (Nt 6934 ins T and Nt 7630-2 A>C). Clinical manifestations of A-T included sluggish ocular tracking, proprioception difficulties, bilateral dysmetria, dysarthric speech, and ataxia.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a right parietal mass that measured 6.4 × 6.0 × 5.6 cm (Fig 1A). A subtotal resection was performed, and the pathologic diagnosis was a malignant glioneuronal tumor. Although not listed in the World Health Organization classification (2007), a malignant glioneuronal tumor has the morphology and behavior of a high-grade astrocytoma (in this case, World Health Organization grade 4) but with a mixed glial/neuronal immunophenotype.1,2 Within the posterior surgical cavity, a residual nodule increased by 30% in size over a 1-month period (Fig 1B). Subsequently, a second subtotal resection was performed, and 10 days postoperatively, additional tumor nodules developed (Fig 1C). As a result of dire clinical circumstances, and on the basis of available scientific data, a therapeutic plan was implemented to include radiotherapy. In vitro colony-survival assay data suggested that approximately one third of the conventional radiotherapy fractionation might yield in vivo efficacy.3 Thus, radiotherapy was titrated by fraction size (and cumulative dose) according to evidence of anatomic and functional MRI response followed by adjuvant therapy including bevacizumab and everolimus.

Fig 1.

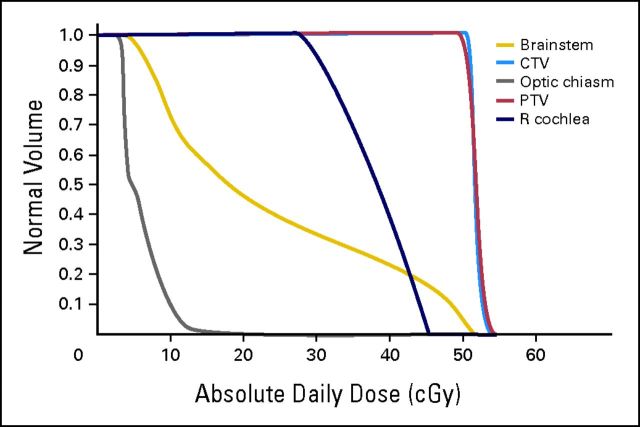

Radiation therapy was divided into two phases. Initially, in vitro data suggested that A-T–deficient tissues may have had an α of 1.6 and β of 0, whereas, in a patients without A-T, α and β would be approximately 0.3 and 0.03, respectively.4 The latter set of α and β values have been ascribed to pediatric glioma cells with an α of 0.3 ± 0.2 and β of 0.03 ± 0.018.5 The dose-volume histogram for phase I of radiotherapy is represented in Figure 2 (CTV, clinical target volume; PTV, planning target volume; R cochlea. right cochlea). Because of these parameters, we initiated a daily radiation regimen of 0.5 Gy for 26 fractions, which led to a tumor control probability of 99.1% (equation 1).

Fig 2.

|

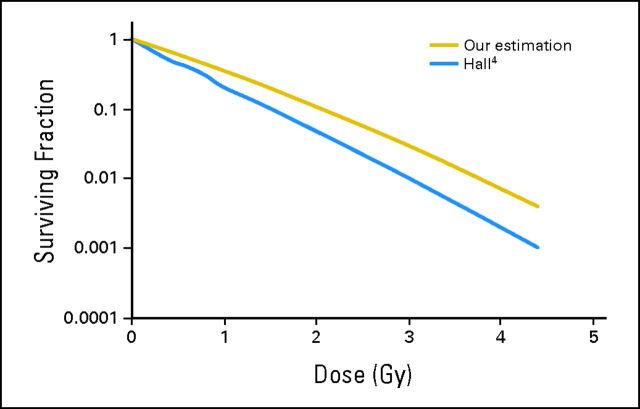

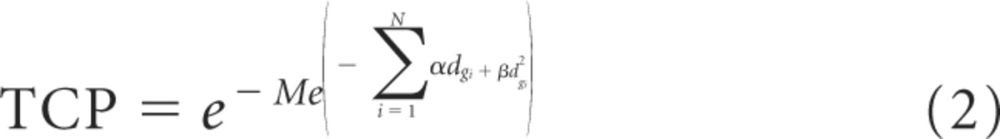

TCP is the tumor control probability; M is the number of clonogens (10 million), and d is the total dose.6 In this model, we assumed little or no repair between the 26 fractions and, thus, a good therapeutic tumor response was expected; however, this probability may not always translate into durable local control. Because α and β were derived from in vitro measurements, weekly MRIs were planned to assess the tumor response throughout radiotherapy. On completion of 10 fractions, a functional/anatomic MRI that included spectroscopy, T2*, and arterial spin labeling revealed a 2-mm increase in the largest transverse residual tumor dimension (Fig 1D). As a result of the minimal acute toxicity, which was noted as alopecia within treatment portals accompanied by erythema and hyperpigmentation without evidence of desquamation, and increased tumor size at this dose/fractionation, a dose increase was warranted. Given the clinical results within the in vivo environment, α was assumed to be smaller than the initial estimation, and β was assumed to be nonzero. An α of 1, which was midway between the A-T in vitro finding and non–A-T, and β of 0.06, which was twice as large as the β value for a non–A-T pediatric glioma, was used as our estimation for this patient (Fig 3). On the basis of these values and equation 1, a dose of 0.75 Gy/fraction for 27 fractions gave a TCP of 99.4%. Because 12 fractions of 0.5 Gy had already been delivered, equation 2, which was a modification of equation 1, was used to calculate the total dose needed for a reasonable TCP.

Fig 3.

|

Here, N id the number of fractions, and dgi was the dose given per fraction. By using equation 2, 12 fractions of 0.5 Gy and 20 fractions of 0.75 Gy, for a total dose of 21 Gy, provided a calculated TCP of 99.7%. Therefore, the second phase of radiation treatment was delivered to similar volumes and included 0.75 Gy/fraction for 20 fractions for a cumulative dose of 21 Gy, which is a dose not that is usually associated with a tumor response in a patient without A-T. Subsequent imaging supported this approach by revealing a rapid response of the tumor to the 0.75 Gy/fraction (Fig 1E). Notably, clinical evaluation revealed a minimal increase in skin reaction to the cumulative dose and modified fractionation.

In the setting of A-T, alkylating agents further increase genomic instability7; therefore, we administered molecular targeted therapy. As a result of the high-grade component of this tumor and possibility of increased telangiectasia or radiation necrosis, bevacizumab was administered as adjuvant chemotherapy.8 Additional therapy included everolimus because of in vitro and in vivo studies that reported activity with everolimus in primitive neuroectodermal tumor/medulloblastoma and glioma models.9 Recently, an institutional phase I study of everolimus combined with bevacizumab was completed in pediatric patients, and the dose combinations administered were documented as safe; however, the maximum tolerated dose remains under investigation (L. McGregor, personal communication, May 2011). Four weeks after completion of irradiation, the patient developed grade 3 skin toxicity in the radiation field. Symptoms improved with topical management (biafine and silvadene). She developed grade 2 mucositis within 1 week of the initiation of everolimus therapy. Medication was withheld for 1 week, and the mucositis resolved. Previous everolimus dosing was resumed without additional complications. The disease remained stable for 6 months and then progressed on imaging. On progression, therapy was changed to cilengitide.10 New symptoms included choreoathetosis of the tongue and increased tremors of questionable etiology (drug versus underlying A-T). After 12 weeks of adjuvant targeted therapy, the patient developed multifocal progressive disease on imaging, with minimal growth at the primary site, and clinically declined, including failure to thrive, short-term memory loss, and fatigue (Fig 1F). She succumbed to disease 14 months after diagnosis.

Discussion

A-T is a multifaceted disease characterized by sensitivity to ionizing radiation and cytotoxic agents and a predisposition to malignancy.7 Although hematopoietic malignancies are more common, a few brain tumors have been reported, and the literature does not support many long-term survivors. Two of the eight reported cases received radiation therapy, and one patient who was followed for 9 months was documented as a survivor in 198711–18; however, long-term follow-up was not reported.

Therapeutic options for brain tumors are limited because conventional dosing of radiation therapy is usually fatal in the setting of severe phenotypic A-T; moreover, the therapeutic window between normal tissue relative to tumor tissue in the CNS of a patient with A-T is unknown.19,20 Clonogenic lymphoblasts have been reported to be up to four-fold more sensitive to irradiation via colony survival assays in tissues from patients with A-T compared with healthy controls.21 However, a lack of radiation-induced cell death in the CNS has been reported in ATM-deficient murine models.22 The paradox of the CNS response in murine models and the aggressive course of the tumor in this patient led to a treatment plan that included radiation therapy with a three-fold reduction from standard radiation dosing for high-grade gliomas (60 Gy).23

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the A-T literature to have received this treatment regimen with minimal acute toxicities. The length of survival was insufficient to assess the full development of late toxicities. Although the patient succumbed to the disease, which was consistent with the course of a high-grade glioma, radiation therapy safely provided prolonged local control within the radiation field. Adjuvant therapy was well tolerated; however, conclusions that address the benefit could not be determined. However, in the event of a patient diagnosed with a brain tumor in the setting of severe phenotypic A-T, clinicians should be aware that an altered fractionation radiotherapy regimen is feasible and may yield local control comparable with malignant high-grade brain tumors in patients without A-T.24,25

Acknowledgment

We thank Julie Groff, BA, for preparation of figures.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varlet P, Soni D, Miquel C, et al. New variants of malignant glioneuronal tumors: A clinicopathological study of 40 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1377–1391. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000143033.36582.40. discussion 1391-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun X, Becker-Catania SG, Chun HH, et al. Early diagnosis of ataxia-telangiectasia using radiosensitivity testing. J Pediatr. 2002;140:724–731. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.123879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall EJ, et al. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. Radiobiology for the Radiologist (ed 5) pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wigg DR, et al. Madison, WI: Medical Physics Publishing; 2001. Applied Radiobiology and Bioeffect Planning; p. 247. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niemierko A, Goitein M. Implementation of a model for estimating tumor control probability for an inhomogeneously irradiated tumor. Radiother Oncol. 1993;29:140–147. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavin MF. Ataxia-telangiectasia: From a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:759–769. doi: 10.1038/nrm2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benesch M, Windelberg M, Sauseng W, et al. Compassionate use of bevacizumab (Avastin) in children and young adults with refractory or recurrent solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:807–813. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guba M, von Breitenbuch P, Steinbauer M, et al. Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth by antiangiogenesis: Involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:128–135. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDonald TJ, Taga T, Shimada H, et al. Preferential susceptibility of brain tumors to the antiangiogenic effects of an α(v) integrin antagonist. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:151–157. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200101000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amariglio N, Hirshberg A, Scheithauer BW, et al. Donor-derived brain tumor following neural stem cell transplantation in an ataxia telangiectasia patient. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masri AT, Bakri FG, Al-Hadidy AM, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia complicated by craniopharyngioma–A new observation. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35:287–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagi K, Mukawa J, Kinjo N, et al. Astrocytoma linked to familial ataxia-telangiectasia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995;135:87–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02307420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamoudi AB, Ertel I, Newton WA JR, et al. Multiple neoplasms in an adolescent child associated with IGA deficiency. Cancer. 1974;33:1134–1144. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197404)33:4<1134::aid-cncr2820330437>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart RM, Kimler BF, Evans RG, et al. Radiotherapeutic management of medulloblastoma in a pediatric patient with ataxia telangiectasia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1237–1240. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groot-Loonen JJ, Slater R, Taminiau J, et al. Three consecutive primary malignancies in one patient during childhood. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1988;5:287–292. doi: 10.3109/08880018809037368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuster J, Hart Z, Stimson CW, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia with cerebellar tumor. Pediatrics. 1966;37:776–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young RR, Austen KF, Moser HW. Abnormalities of serum γ-1-a globulin and ataxia telangiectasia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1964;43:423–433. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196405000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiloh Y. The ATM-mediated DNA-damage response: Taking shape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinnon PJ. ATM and ataxia telangiectasia. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:772–776. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huo YK, Wang Z, Hong JH, et al. Radiosensitivity of ataxia-telangiectasia, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, and related syndromes using a modified colony survival assay. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2544–2547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog KH, Chong MJ, Kapsetaki M, et al. Requirement for Atm in ionizing radiation-induced cell death in the developing central nervous system. Science. 1998;280:1089–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker MD, Green SB, Byar DP, et al. Randomized comparisons of radiotherapy and nitrosoureas for the treatment of malignant glioma after surgery. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1323–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012043032303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Neyns B, et al. Phase I/IIa study of cilengitide and temozolomide with concomitant radiotherapy followed by cilengitide and temozolomide maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2712–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polley MY, Lamborn KR, Chang SM, et al. Six-month progression-free survival as an alternative primary efficacy endpoint to overall survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients receiving temozolomide. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:274–282. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]