Abstract

Context:

Intraoperative cytology and frozen section play an important role in the diagnosis of neurosurgical specimens. There are limitations in both these procedures but understanding the errors and pitfalls may help in increasing the diagnostic yield.

Aims:

To find the diagnostic accuracy of intraoperative cytology and frozen section for central and peripheral nervous system (PNS) lesions and analyze the errors, pitfalls, and limitations in these procedures.

Settings and Design:

Eighty cases were included in this prospective study in a span of 1.5 years.

Materials and Methods:

The crush preparations and the frozen sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin method. The diagnosis of crush smears and the frozen sections were compared with the diagnosis in the paraffin section, which was considered as the gold standard.

Statistical Analyses Used:

Diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

Results:

The diagnostic accuracy of crush smears was 91.25% with a sensitivity of 95.5% and specificity of 100%. In the frozen sections, the overall diagnostic accuracy was 95%, sensitivity was 96.8%, and specificity was 100%. The categories of pitfalls noted in this study were categorization of spindle cell lesions, differentiation of oligodendroglioma from astrocytoma in frozen sections, differentiation of coagulative tumor necrosis of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) from the caseous necrosis of tuberculosis, grading of gliomas in frozen section, and differentiation of the normal granular cells of the cerebellum from the lymphocytes in cytological smears.

Conclusions:

Crush smear and frozen section are complimentary procedures. When both are used together, the diagnostic yield is substantially increased.

Keywords: Central nervous system (CNS) tumors, crush smear, frozen section, intraoperative diagnosis, pitfalls

Introduction

The role of intraoperative pathological diagnosis is crucial in neurosurgery. The goal of the pathologist is to guide the neurosurgeon in making clinically relevant intraoperative decisions, which enable the surgeon to plan the extent of surgery and modify it accordingly. The pathologist tries to give the maximum possible intraoperative information keeping in mind the clinical symptoms and radiological features; still, there are various limiting factors.[1]

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of crush smear and frozen section in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) lesions and to analyze the possible errors, pitfalls, and limitations of these procedures keeping histopathology as the gold standard.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted on 90 neurosurgical specimens that included biopsies from both the brain and spinal cord lesions received in our department over a period of 1.5 years (January 2010 to September 2011). A total of 80 cases were studied while 10 cases were excluded due to the inadequacy of samples. Samples for crush smears and frozen sections were received in normal saline. A tiny portion of the sample from the representative site was crushed between two glass slides to prepare smears. The smears were stained with hematoxylin and eosin method.[2] A part or whole of the residual sample was submitted for frozen sections and stained similarly. The remaining sample was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and submitted for paraffin sections. Immunohistochemistry and special stains were performed wherever needed for the diagnosis. All the cases were evaluated by history, clinical examinations, and radiological investigations. A rapid opinion about the benign or malignant nature of the lesion and the type of tumor was given, which were later correlated with the histological observations of the paraffin-embedded section, later being taken as the gold standard. The discordant cases were identified and the possible reasons for the fallacies were analyzed.

Results

Of the total 80 cases, 87.5% (70/80) of the lesions were from the CNS and 12.5% (10/80) were PNS lesions. Gliomas were the predominant lesion among brain tumors (34.2%, 24/70) while meningiomas were the most common spinal tumors (30%, 3/10). The brain tumors were mostly crushable [77.1% (54/70)] while the spinal tumors, especially fibroblastic meningiomas and schwannomas, posed a considerable problem in making a good smear [70% (7/10)].

The overall diagnostic accuracy of crush smears in the present study was 91.25% with a sensitivity of 95.5% and specificity of 100%. In the frozen sections, the overall diagnostic accuracy was 95%, while sensitivity and specificity were 96.8% and 100%, respectively.

Assessment of crush smears yielded five discordant cases and in four cases there was a problem in the grading of astrocytic neoplasms. In contrast, the evaluation of frozen section also had five cases with discordant diagnosis and in two cases there were problems in the grading of astrocytomas.

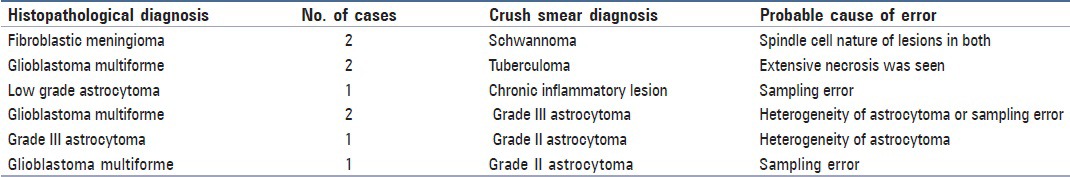

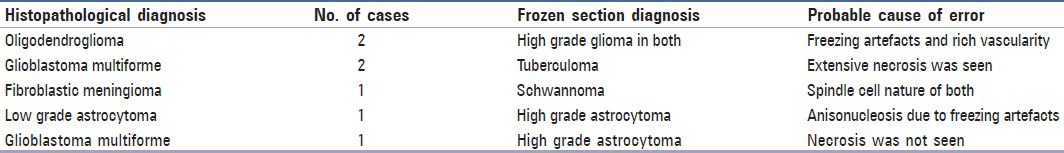

The discrepancies encountered during the process of reporting crush smears and frozen sections, along with the final histological diagnosis and the probable causes of error, are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Discrepancies in crush smear diagnosis

Table 2.

Discrepancies in frozen section diagnosis

Various technical errors were noted in the frozen sections, the predominant being freezing artefacts followed by sampling and interpretative errors. In the crush smears, there was discordance in diagnosis mainly due to sampling and interpretative errors.

Discussion

Intraoperative diagnosis of CNS and PNS lesions is an important preliminary diagnostic tool to distinguish neoplastic from nonneoplastic lesions, which helps the neurosurgeon to plan further management of the patient. An accurate intraoperative diagnosis rests on good correlation of clinical, radiological, and microscopic findings. The careful and judicious interpretation of the above details leads to a good diagnostic yield.

In this study, it was noted that brain tumors were predominantly crushable while spinal tumors were difficult to crush and make smears. Due to the soft and friable nature of brain tumors, a majority of these could be smeared easily and hence, yielded good cytomorphological details. The above findings were in accordance with the previous studies.[1,3,4] This might have also been due to the fact that most of the brain tumors were gliomas, which are soft and easily crushable while most of the spinal tumors were meningiomas and schwannomas, which are firm in nature and thus, are difficult to crush and prepare a good smear.

Crush smears yielded good cytomorphological details in cases of astrocytoma, meningothelial variant of meningioma, oligodendroglioma, ependymoblastoma, metastatic carcinoma, and pituitary adenoma while frozen sections fared well in inflammatory lesions, fibroblastic meningioma, schwannoma, and ependymoma.

Various limitations were noted in both the procedures. Due to the soft and friable nature of brain tumors, these were difficult to section in frozen section and the sections showed marked freezing artefacts due to ice crystal formation resulting in anisonucleosis and nuclear hyperchromasia. Thicker sections led to folding of sections and loss of sections from the surface of the slides due to poor adherence during staining procedures. In contrast, lesions that were firm in consistency such as fibroblastic meningioma, schwannoma, inflammatory lesions, ependymoma, and metastatic carcinomas yielded good quality frozen sections. Other authors have also reported frozen section to be better than crush smear in diagnosing inflammatory lesions.[1,4]

Categories of discrepancies noted in the present study are:

-

Typing of spindle cell lesions both in crush smear and frozen section

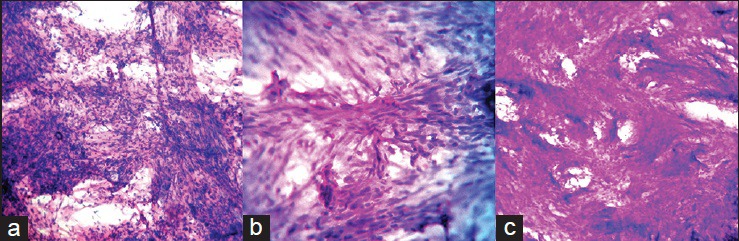

Two cases of fibroblastic meningioma in crush smears were misinterpreted as schwannoma since the spindle cells of fibroblastic meningioma formed fascicles in smears without any prominent meningothelial whorls [Figure 1a and b]. Similar discrepancies were also noted in the study by Mitra et al.[5]

One case of fibroblastic meningioma in frozen section was misdiagnosed as schwannoma because of the spindle cell nature of both [Figure 1c]. Distinguishing fibroblastic meningiomas, peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and other spindle cell proliferations can be challenging in frozen section and crush smear because of the limited tissue available for diagnosis and the thick sections that make it difficult to assess these spindle cell tumors.

It is well-comprehended that cerebellopontine angle meningiomas can show a predominantly benign spindle cell appearance with thick-walled blood vessels and abundant collagen, which can often be misinterpreted as schwannoma.[6]

The interpretative errors in frozen sections are mainly due to the freezing process that distorts the architecture. Variable section thickness and uneven staining obscure the cytologic details and influence subjective judgement. A thorough knowledge of surgical anatomy and expertise in the interpretation of neural tissues is essential to reduce interpretative errors.[7]

-

Differentiating oligodendroglioma from astrocytoma in frozen sections

In the present study, there was a problem in assessing oligodendroglioma in frozen section, which was misdiagnosed as high grade astrocytoma. First, this was since the oligodendroglial cells were seen angulated similar to astrocytes due to freezing artefacts. Second, high vascularity, which is a feature of oligodendroglioma, was misinterpreted as vascular proliferation of high grade astrocytoma. However, crush smear in both the cases yielded correct diagnosis. Mitra et al. and Plesac and Prayson have also reported similar problems. It is pertinent to mention that the perinuclear halo that is seen in paraffin sections due to fixation artefacts, which give a clue to the oligodendroglial nature of cells, are absent in frozen section.[5,6]

-

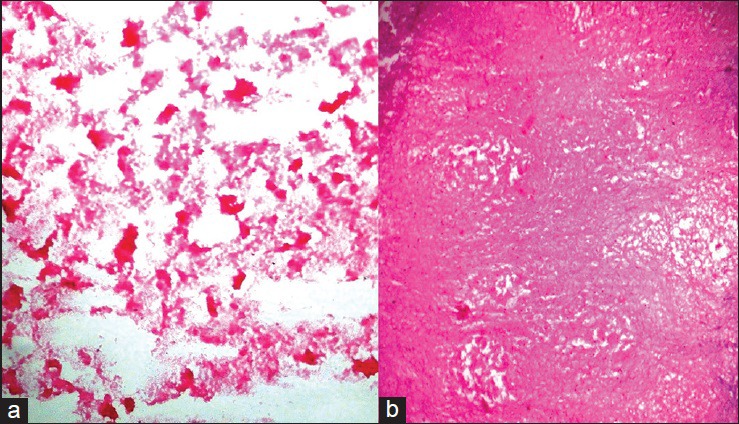

Differentiating the coagulative tumor necrosis of glioblastoma multiforme from the caseous necrosis of tuberculoma

Two cases of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) were misdiagnosed as tuberculoma due to sampling error. In both the cases, the necrotic areas were sampled and both the crush smears and frozen section yielded only necrotic tissue with very few viable cells [Figures 2a and b]. These cases were diagnosed as GBM in subsequent paraffin sections where extensive areas of coagulative necrosis was seen, along with viable malignant cells. Mitra et al. and Plesec and Prayson also reported similar findings in their studies.[5,6] Sampling error (gross or microscopic) is one of the most common causes of discrepancy. Thorough sampling and technically adequate sections are recommended to reduce intraoperative frozen section discrepancies.[7]

-

Problem in tumor grading in astrocytoma

Although it is not essential to accurately grade CNS tumors during intraoperative diagnosis, an attempt was made in the present study, and results were compared with final histopathological grade.

Incorrect assessment of grading of astrocytomas was seen in four cases in crush smear and two cases in frozen section. The most commonly faced problem was with glioblastoma consisting of three cases and one case each of anaplastic astrocytoma and grade II astrocytoma.

The first case of GBM was misreported as grade II astrocytoma in cytological smears probably due to sampling error from the peritumoral areas. It was correctly diagnosed in frozen section, which revealed the pseudopalisading necrosis, along with high grade cytological features.

The second case of GBM was misinterpreted as grade III astrocytoma in cytology while it was correctly interpreted in frozen section for the reason cited above in the first case. This shows the advantage of frozen section over crush smears, in which a study of the entire tissue architecture becomes indispensible.

The third case of GBM was also assessed as grade III astrocytoma, both in cytology and in frozen section. In this case, necrosis could not be appreciated either in the smear or in the tissue sections although cytological features of high grade glioma were apparent.

A case of grade III astrocytoma was diagnosed as grade II in smears, which may have been due to heterogeneity of the tumoral lesion. This fallacy could have been avoided by taking samples from the multiple areas of the specimen.

Finally, there was a case of grade II astrocytoma that was erroneously diagnosed as grade III in frozen section as it showed enhanced anisonucleosis, which was possibly a result of freezing artefact. However, it was correctly interpreted in crush smear.

This problem in the grading of astrocytomas, either overgrading or undergrading, was also reported by other authors.[8,9,10,11] Most of the available studies have attributed this to the heterogeneity of astrocytomas. In case of frozen section, this problem is encountered due to freezing artefacts, which enhances nuclear anisonucleosis and incorrectly resembles a higher grade of tumor. Improper grading of astrocytic neoplasms in cytologic preparations has also been documented by other authors.[12,13,14] According to some, it is inappropriate to attempt to grade CNS neoplasms on small biopsy material whether by smear or frozen technique as astrocytomas are known for their heterogeneity. Paraffin sections showed that in undergraded cases, there were areas of both high and low grade types and cytological sampling might have failed to show the anaplastic areas.[13,14]

-

Problem in differentiating normal granular cells of the cerebellum from the lymphocytes

In the present study, we encountered one case of grade II astrocytoma of the cerebellum, which was misdiagnosed as chronic inflammatory lesion. This was due to sampling error from the normal areas of the cerebellum, in which normal granular cells were mimicked as lymphocytes on cytological preparation. Iqbal et al.[15] have also noted that during assessment of smears from lesions of the cerebellum, granular cells of the cerebellum are often confused with inflammatory cells, tumor cells of primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), lymphoma, other small round cell tumors, or medulloblastoma. They stressed that a careful search for Purkinje cells among these small blue round cells may possibly help to identify them as normal granular cells. However, in our case Purkinje cells were not seen among the granular cells, which led to the misinterpretation. However, in the frozen section the correct diagnosis of low grade astrocytoma was made as the total tissue architecture could be seen, i.e., the tumoral area was surrounded by the normal cerebellar tissue. This case outlines the advantage of frozen section over cytological preparations.

Overall, the results of the present study were comparable with most studies, in terms of achieving more than 90% accuracy in both the techniques. The diagnostic accuracy of crush smears in this study was 91.25%, which was equivalent to other studies.[1,5,10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] The diagnostic accuracy of frozen section was 95%, which was comparable to other studies.[5,14,16]

It was found that frozen section technique was superior to crush smear in all cases, especially in lesions that were difficult to smear during the process of intraoperative diagnosis. Savargoankar and Farmer, Mitra et al. and Reyes et al.[4,5,16] have also found that frozen sections were better than crush smear for intraoperative diagnosis. Iqbal et al.[15] had reported a sensitivity of 95.36% in crush smear and Pawar et al.[11] obtained a sensitivity of 91.6% and specificity of 100% in crush smear, which is equivalent to that in the present study.

In this study, it was found that both crush smear and frozen section were complementary procedures. When both were used together, the diagnostic yield was markedly increased. Other studies such as that of Rao et al.[1] and Di Steffano et al.[9] also favored this. They reported that the diagnostic accuracy increased to 95.29% when both these procedures were used. Other authors[8,16] also advocated the same thing and recommended the use of both frozen section and crush preparation for intraoperative diagnosis as these complement each other — cytomorphology is preserved in crush smears while frozen sections lack the cytological detail but preserve tissue architecture.

Figure 1.

(a) Crush smear showing spindle cells of fibroblastic meningioma arranged in fascicles without meningothelial whorls, which was misinterpreted as schwannoma (H and E, ×200) (b) Crush smear of the same case showing the fascicular arrangement of spindle cells (H and E, ×400) (c) Frozen section of fibroblastic meningioma misinterpreted as schwannoma showing the spindle cell nature of the lesion due to thick sections (H and E, ×200)

Figure 2.

(a) Crush smear showing coagulative necrosis of glioblastoma multiforme, which was misinterpreted as caseous necrosis of tuberculoma (H and E, ×200) (b) Frozen section showing only coagulative necrosis of glioblastoma multiforme with no malignant cells, which was misinterpreted as tuberculoma (H and E, ×200)

Conclusion

To conclude, cytology has emerged as the preferred method for intraoperative diagnosis, given the advantage of enhanced cellular morphology and lack of artifacts encountered in frozen sections. Hence, it is recommended that intraoperative cytology be used for rapid diagnosis of CNS and PNS lesions, especially in developing countries such as India where the supply of electricity is irregular and the cost of cryostat and availability of technicians are prohibitive. The knowledge of the artefacts encountered in frozen section and the distinctive cytological features in smear will help in reaching a correct diagnosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rao S, Rajkumar A, Ehtesham MD, Duvuru P. Challenges in neurosurgical intraoperative consultation. Neurol India. 2009;57:464–8. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.55598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2008. pp. 126–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shukla K, Parikh B, Shukla J, Trivedi P, Shah B. Accuracy of cytological diagnosis of central nervous system tumours in crush preparation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:483–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savargoankar P, Farmer PM. Utility of intra-operative consultations for the diagnosis of central nervous system lesions. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2001;31:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitra S, Mohan K, Sharma V, Mukhopadhya D. Squash preparation: A reliable diagnostic tool in the intraoperative diagnosis of central nervous system tumors. J Cytol. 2010;27:81–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.71870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plesec TP, Prayson RA. Frozen section discrepancy in the evaluation of central nervous system tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1532–40. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1532-FSDITE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandour-Edwards RF, Donald PJ, Boggan JE. Intraoperative frozen section diagnosis in skull base surgery. Skull Base Surg. 1993;3:159–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1060580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folkerth RD. Smears and frozen sections in the intraoperative diagnosis of central nervous system lesions. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1994;5:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Stefano D, Scucchi LF, Cosentino L, Bosman C, Vecchione A. Intraoperative diagnosis of nervous system lesions. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:346–56. doi: 10.1159/000331614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slowiński J, Harabin-Slowińska M, Mrówka R. Smear technique in the intra-operative brain tumor diagnosis: Its advantages and limitations. Neurol Res. 1999;21:121–4. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1999.11740907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawar N, Deshpande K, Surase S, D’costa G, Balgi S, Goel A. Evaluation of the squash smear technique in the rapid diagnosis of central nervous system tumors: A cytomorphological study. ISPUB. 2010;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kini JR, Jeyraj V, Jayaprakash CS, Indira S, Naik CN. Intraoperative consultation and smear cytology in the diagnosis of brain tumours. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2008;6:453–7. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v6i4.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asha T, Shankar SK, Rao TV, Das S. Role of squash-smear technique for rapid diagnosis of neurosurgical biopsies: A Cytomorphological evaluation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1989;32:152–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah AB, Muzumdar GA, Chitale AR, Bhagwati SN. Squash preparation and frozen section in intraoperative diagnosis of central nervous system tumors. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:1149–54. doi: 10.1159/000332104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iqbal M, Shah A, Wani MA, Kirmani A, Ramzan A. Cytopathology of the central nervous system. Part 1. Utility of crush smear cytology in intraoperative diagnosis of central nervous system lesions. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:608–16. doi: 10.1159/000326028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reyes MG, Homsi MF, McDonald LW, Glick RP. Imprints, smears and frozen sections of brain tumors. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:575–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199110000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkeley BB, Adams JH, Doyle D, Graham DI, Harper GG. The smear technique in the diagnosis of neurosurgical biopsies. N Z Med J. 1978;87:12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liwnicz BH, Henderson KS, Masukawa T, Smith RD. Needle aspiration cytology of intracranial lesions: A review of 84 cases. Acta Cytol. 1982;26:779–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall LF, Adams H, Doyle D, Graham DI. The histological accuracy of the smear technique for neurosurgical biopsies. J Neurosurg. 1973;39:82–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.39.1.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostertag CB, Mennel HD, Kiessling M. Stereotaxic cytology of brain tumors. Surg Neurol. 1980;14:275–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qureshi IA, Jamal S, Mamoon N, Mushtaq S, Luqman M, Sharif MA. Cytomorphological spectrum of neurosurgical lesions by crush smears cytology. PAFMJ. 2009;2:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chimelli L, Campos Ide S. Value of the smear in the preoperative diagnosis of tumors removed in neurosurgeries. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1993;51:190–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1993000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]