Abstract

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) indirectly stimulates bone formation, but little is known about its direct effect on bone formation. In this study, we observed that 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances adipocyte differentiation, but inhibits osteoblast differentiation during osteogenesis. The positive role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in adipocyte differentiation was confirmed when murine osteoblasts were cultured in adipogenic medium. Additionally, 1,25(OH)2D3 enhanced the expression of adipocyte marker genes, but inhibited the expression of osteoblast marker genes in osteoblasts. The inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and promotion of adipocyte differentiation mediated by 1,25(OH)2D3 were compensated by Runx2 overexpression. Our results suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 induces the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes via Runx2 downregulation in osteoblasts.

Keywords: 1,25(OH)2D3; transdifferentiation; osteoblast; adipocyte

1. Introduction

Bone is an important organ for supporting the body and regulating mineral homeostasis. Bone is continuously remodeled by two cell types: osteoclasts and osteoblasts [1]. Osteoclasts resorb old bone and osteoblasts produce the bone matrix [2,3]. Various factors, such as the paratyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), regulate bone homeostasis by modulating bone cells [2,4].

The steroid hormone 1,25(OH)2D3 is a key regulator of calcium homeostasis and skeletal health [5]. In bone, 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates mineralization both in an indirect and a direct manner. 1,25(OH)2D3 increases calcium absorption from the intestines, which indirectly stimulates bone formation [6]. It can also directly influence bone formation via the regulation of osteoblast differentiation and function. Various studies have demonstrated the direct effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on osteoblast differentiation and function in vitro. However, the results of these studies are highly controversial. Several studies have shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates osteoblast differentiation by increasing alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and osteocalcin expression in human primary osteoblast-like cells [7,8,9]. However, several lines of evidence suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation. For example, 1,25(OH)2D3 downregulates osteocalcin expression in mouse calvaria 3T3 (MC3T3)-E1 osteoblasts [10]. Lieben et al. [11] have also reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 impairs mineralization by upregulating the expression of mineralization inhibitors in mouse primary osteoblasts.

Osteoblasts, which are responsible for bone formation, are derived from mesenchymal stem cells by the action of several transcription factors, including Runx2, osterix, and β-catenin [12]. In particular, Runx2, a cell-specific member of the Runt family of transcription factors, is essential for mesenchymal cell differentiation into osteoblasts. Runx2 promotes the acquisition of an osteoblastic phenotype by mesenchymal stem cells by inducing the expression of genes encoding major bone matrix proteins, e.g., Col1a1, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein (BSP), and osteocalcin [11,12]. Runx2−/− mice exhibit a complete lack of intramembranous and endochondral ossification in vivo and Runx2−/− calvarial cells cannot differentiate into osteoblasts, even in the presence of osteogenic factors in vitro [12,13,14]. Multiple factors that play an important role in osteoblast differentiation via the regulation of Runx2 expression or activation have been identified.

Adipocytes as well as osteoblasts are derived from mesenchymal stem cells. Various transcription factors, such as CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α (CEBP-α), CEBP-β, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), are essential for mesenchymal cell differentiation into adipocytes [15]. Increased adipose tissue in the bone marrow of osteoporotic patients and individuals with age-dependent bone loss may be associated with the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes [16]. While the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the transdifferentiation of skeletal muscle cells to adipose cells is known, it is not clear if 1,25(OH)2D3 is involved in the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes in the bone marrow [17].

To elucidate the direct effect of locally produced 1,25(OH)2D3 on bone formation, we investigated the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on osteoblast differentiation, Runx2 expression, and the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes.

2. Results

2.1. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) Inhibits Osteoblast Differentiation and Runx2 Expression in Primary Osteoblasts

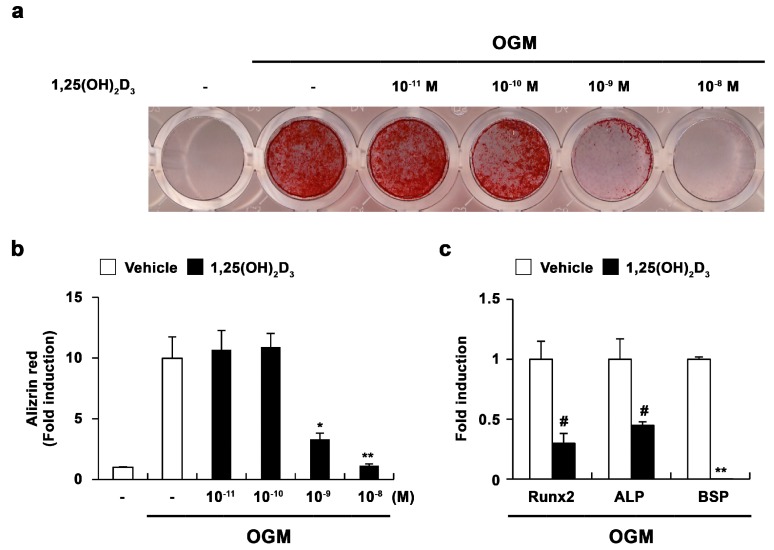

To elucidate the direct effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on bone formation, we examined its role in osteoblast differentiation. When mouse primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium including bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2), ascorbic acid, and β-glycerophosphate, bone nodule formation was dramatically induced (Figure 1a,b). However, supplementation with 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly inhibited osteoblast differentiation induced by the osteogenic medium in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1a,b). The negative effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on osteogenesis was confirmed by the expression of osteoblast differentiation-related genes. As shown in Figure 1c, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the expression of osteoblastic genes, such as Runx2, ALP, and BSP. Therefore, 1,25(OH)2D3 may negatively regulate osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting the expression of Runx2 and its downstream targets ALP and BSP.

Figure 1.

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) inhibits osteoblast differentiation. (a–c) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM) with vehicle or increasing concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. (a) Cultured cells were fixed and stained with Alizarin red; (b) Alizarin red staining was quantified by densitometry at 562 nm; (c) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM) containing either vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M). The mRNA levels of Runx2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and bone sialoprotein (BSP) were analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). # p < 0.05; * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001 as compared with controls.

2.2. 1,25(OH)2D3 Induces the Transdifferentiation of Osteoblasts to Adipocytes

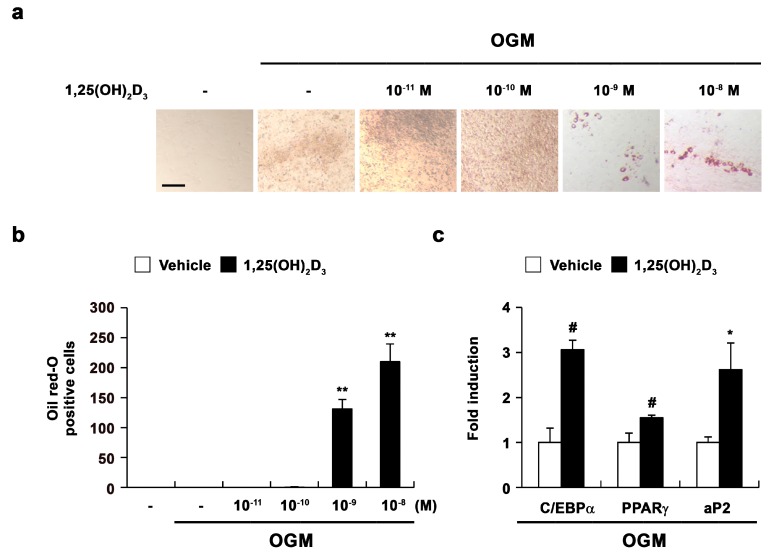

Intriguingly, 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment during osteoblast differentiation resulted in lipid droplet formation with the inhibition of bone nodule formation. Therefore, we examined the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on adipocyte differentiation during osteoblast differentiation. Osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium either without or with 1,25(OH)2D3. Positive Oil Red-O staining confirmed the presence of lipid droplets, which were primarily observed in osteoblasts treated with high concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 2a,b). Additionally, 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly increased the expression of adipocyte marker genes, including CEBP-α, PPAR-γ, and adipocyte protein 2 (aP2), compared with control cells. These results indicated that 1,25(OH)2D3 can induce the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes during osteoblast differentiation.

Figure 2.

1,25(OH)2D3 induces transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. (a–c) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM) with vehicle or increasing concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. (a) Cultured cells were fixed and stained with Oil Red-O, Bar: 50 µm; (b) The number of Oil Red-O—positive cells was counted; (c) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM) containing either vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M). The mRNA levels of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α (CEBP-α), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), and adipocyte protein 2 (aP) were analyzed by real-time PCR. # p < 0.05; * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001 as compared with controls.

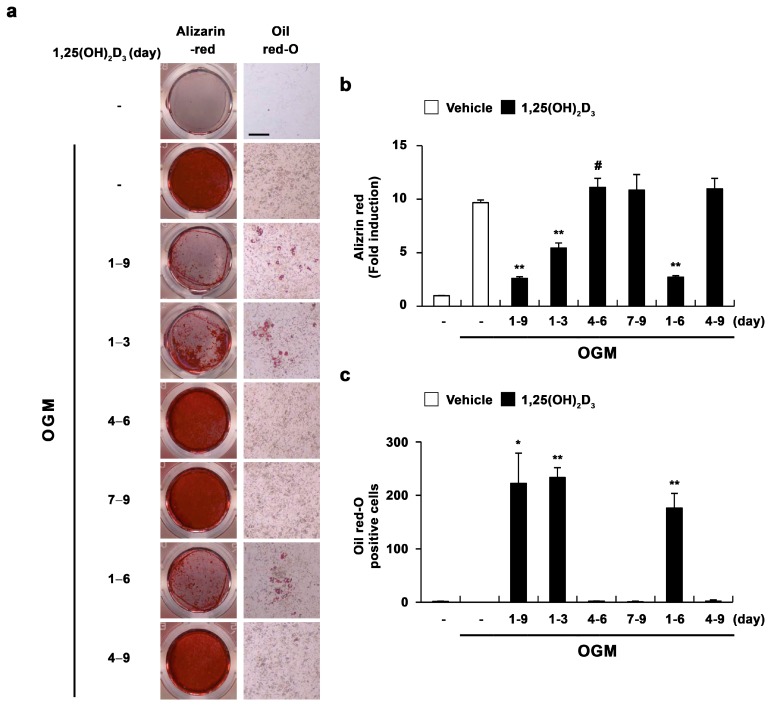

Next, we assessed the time course of the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. When 1,25(OH)2D3 was added continuously from the start of osteoblast differentiation (days 1–9), adipocyte differentiation was dramatically enhanced, while osteoblast differentiation was significantly reduced (Figure 3). Only the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 added from day 1 to day 6 was comparable to that of 1,25(OH)2D3 added continuously from the start of osteoblast differentiation (i.e., days 1–9) (Figure 3). However, the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 during the late stage of osteoblast differentiation (days 7–9) did not affect the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. Interestingly, the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes was dependent on the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 during the initial three days of osteoblast differentiation (Figure 3). Taken together, these results demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 primarily acts at the early stage of osteoblast differentiation to induce the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes.

Figure 3.

1,25(OH)2D3 induces the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes at the early stage of osteoblast differentiation. (a–c) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM). Cells were treated with either vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M) during the indicated time periods. (a) Cultured cells were fixed and stained with Alizarin red or Oil Red-O, Bar: 50 µm; (b) Alizarin red staining was quantified by densitometry at 562 nm; (c) The number of Oil Red-O—positive cells was counted. # p < 0.05; * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001 as compared with controls.

2.3. 1,25(OH)2D3 Induces Adipocyte Differentiation in Osteoblasts

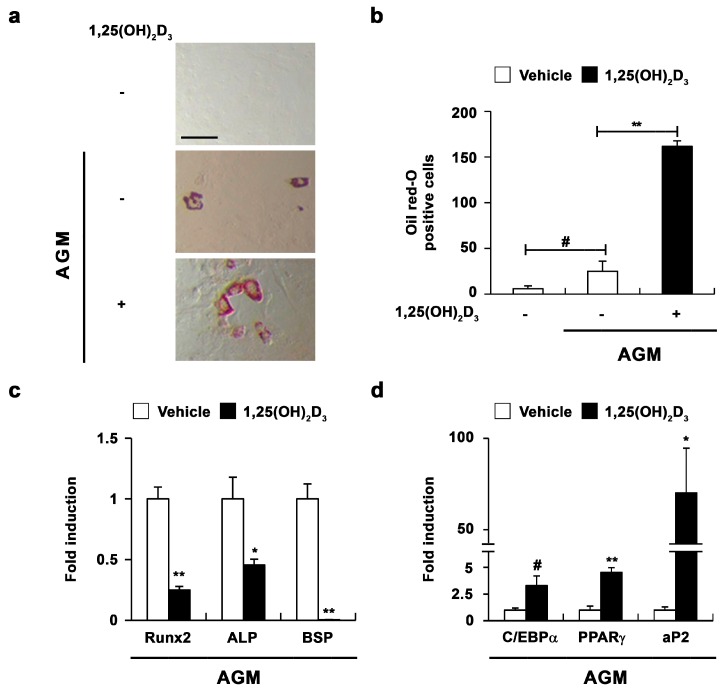

To confirm the role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in osteoblasts, we investigated the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 during adipocyte differentiation of osteoblasts. When mouse primary osteoblasts were cultured in adipogenic medium including insulin, dexamethasone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), and rosiglitazone, the formation of lipid droplets was slightly induced (Figure 4a,b). As shown in Figure 4, 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly enhanced lipid droplet formation induced by adipogenic medium (Figure 4a,b). Additionally, 1,25(OH)2D3 increased the expression of adipocyte marker genes, but decreased the expression of osteoblast marker genes (Figure 4c,d). These results suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates not only osteoblast differentiation, but also adipocyte differentiation in osteoblasts.

Figure 4.

1,25(OH)2D3 induces adipocyte differentiation in primary osteoblasts. (a–d) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in adipogenic medium (AGM) containing either vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M). (a) Cultured cells were fixed and stained with Oil Red-O, Bar: 50 µm; (b) The number of Oil Red-O—positive cells was counted; (c) The mRNA levels of Runx2, ALP, and BSP were analyzed by real-time PCR; (d) The mRNA levels of CEBP-α, PPAR-γ, and aP2 were analyzed by real-time PCR. # p < 0.05; * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001 as compared with controls.

2.4. 1,25(OH)2D3 Induces the Transdifferentiation of Osteoblasts to Adipocytes via the Regulation of Runx2 Expression

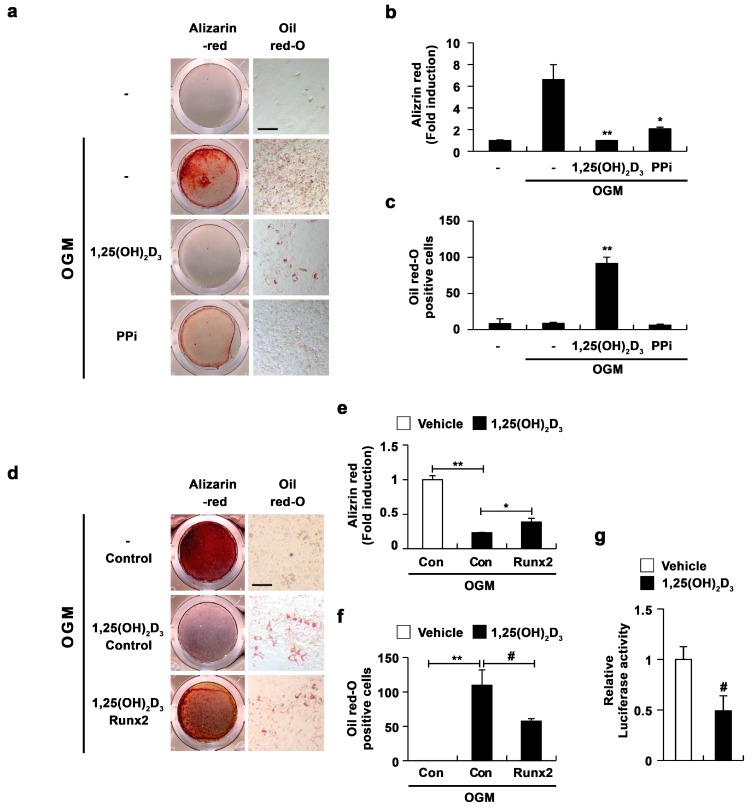

It has recently been reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 mediates the suppression of mineral incorporation via the upregulation of pyrophosphate (PPi) levels [11]; accordingly, we analyzed whether increased PPi levels due to 1,25(OH)2D3 are involved in the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. The addition of PPi to cultured osteoblasts suppressed osteoblast differentiation, similar to treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 5a,b). However, PPi did not induce the formation of lipid droplets during osteoblastogenesis (Figure 5a,c). Therefore, these results indicated that increased PPi levels in response to 1,25(OH)2D3 are involved in the inhibitory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on mineralization, but not in the stimulatory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the formation of lipid droplets.

Figure 5.

1,25(OH)2D3 induces transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes by inhibiting Runx2 expression. (a–c) Primary osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM) with vehicle, 1,25(OH)2D3, or PPi as indicated. (a) Cultured cells were fixed and stained with Alizarin red or Oil Red-O, Bar: 50 µm; (b) Alizarin red staining was quantified by densitometry at 562 nm; (c) The number of Oil Red-O–positive cells was counted; (d–f) Osteoblasts were transduced with pMX-IRES-EGFP (control) or Runx2 retrovirus. Transduced osteoblasts were cultured in osteogenic medium (OGM) with vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3. (d) Cultured cells were fixed and stained with Alizarin red or Oil Red-O, Bar: 50 µm; (e) Alizarin red staining was quantified by densitometry at 562 nm; (f) The number of Oil Red-O—positive cells was counted; (g) C2C12 cells were transfected with a Runx2 reporter construct. Transfected cells were treated with vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 h. Luciferase activity was measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The data represent means and SD of triplicate samples. # p < 0.05; * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001 as compared with controls.

Since 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the expression of Runx2 (Figure 1c), we next analyzed whether the inhibitory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on Runx2 expression regulates adipocyte differentiation during osteoblast differentiation. The overexpression of Runx2 restored the decrease in osteoblast differentiation as well as the increase in adipocyte differentiation regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 5d,f). Moreover, the inhibitory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on Runx2 expression was confirmed by the 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated suppression of Runx2 promoter activity (Figure 5g). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the downregulation of Runx2 by 1,25(OH)2D3 in osteoblasts results in the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation accompanied by the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. However, because Runx2 overexpression did not completely reverse the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation, there remains a possibility that 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes through unknown pathways other than Runx2 regulation.

3. Discussion

It is generally accepted that 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates bone formation by increasing calcium absorption from the intestines [6]. However, the role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in bone formation mediated by osteoblasts is still largely unclear. Here, we showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 directly suppressed osteoblast differentiation, potentially as a result of Runx2 inhibition.

Runx2 is a key transcription factor that initiates and regulates the early stage of osteoblast differentiation. An inhibitory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on osteoblast differentiation was observed when 1,25(OH)2D3 was added at the early stage, rather than the late stage of osteoblast differentiation. Furthermore, 1,25(OH)2D3 suppressed the expression of Runx2 during osteoblast differentiation, which in turn inhibited the expression of downstream genes, such as ALP and BSP. Similarly, it has been reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 suppresses Runx2 expression within 24 h in MC3T3 and rat osteosarcoma (ROS) 17/2.8 cells via the binding of vitamin D receptor (VDR) to vitamin D response element (VDRE) and Runx2 autonomously suppresses its own expression [18]. In contrast, Han et al. [19] reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 increases Runx2 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells and induces vascular calcification. These findings suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits bone formation by suppressing Runx2 expression in osteoblasts, but the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on bone mineralization may be dependent on the cell-type specificity of Runx2 expression regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3.

The direct effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on adipocyte differentiation is not yet clear. Several studies have reported a negative role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in adipogenesis [20,21,22]. However, it has also been reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes the maturation of human subcutaneous preadipocytes via a PPAR-γ-independent pathway [23]. Previous studies have indicated that 1,25(OH)2D3 does not directly induce critical early factors for adipocyte differentiation. 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated inhibition of osteoblast differentiation accompanied by an increase in lipid droplet formation suggests an important role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. Previous results have also shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 can induce the formation of lipid droplets in osteoblasts [24]. Similarly, we observed that 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulated the formation of lipid droplets, even in osteogenic medium that lacked adipogenic stimulators. The formation of lipid droplets in osteoblasts was more highly stimulated in 1,25(OH)2D3-containing osteogenic medium than in adipogenic medium including insulin, dexamethasone, IBMX, and rosiglitazone. Therefore, the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 is involved in the regulation of osteoblastic genes, rather than the induction of adipogenic genes. Runx2 inhibits the late adipocyte maturation of human bone marrow precursor cells and Runx2-deficient osteoblasts spontaneously undergo adipocyte differentiation with the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation [25,26,27]. In our study, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited Runx2 expression and the overexpression of Runx2 suppressed the formation of lipid droplets induced by 1,25(OH)2D3, suggesting that Runx2 downregulation mediated by 1,25(OH)2D3 induces the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes. Recently, it has been reported that adipocytes support osteoclast differentiation and function via receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) production [28]. It is also well known that 1,25(OH)2D3 indirectly induces osteoclast differentiation via RANKL upregulation in osteoblasts [29,30]. 1,25(OH)2D3 may primarily enhance RANKL in osteoblasts and secondarily enhance RANKL by increasing adipocyte differentiation. Although vitamin D supplementation indirectly increases bone mass by improving intestinal calcium absorption, the administration of high-dose vitamin D to older woman results in an increased fracture risk [31,32]. Vitamin D might have several roles in osteoblasts, including the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation, promotion of adipocyte differentiation, and the support of osteoclast differentiation, and these functions may result in unexpected deleterious effects of vitamin D on the skeleton.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Recombinant human BMP2 was purchased from Cowellmedi (Busan, Korea). Alizarin red, β-glycerophosphate, insulin, dexamethasone, 3-isobytyl-1-methylxanthine, Oil Red-O, rosiglitazone, and 1,25(OH)2D3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ascorbic acid was purchased from Junsei Chemical (Tokyo, Japan).

4.2. Osteoblast Differentiation

Primary osteoblast precursor cells were isolated from neonatal mouse calvaria by digestion with 0.1% collagenase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 0.2% dispase II (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Isolated osteoblast precursor cells were cultured in α-Minimal Essential Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. For osteoblast differentiation, primary osteoblast precursor cells were cultured in osteogenic medium containing BMP2 (100 ng/mL), ascorbic acid (50 µg/mL), and β-glycerophosphate (100 mM) for six to nine days. Cultured cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 40 mM alizarin red (pH 4.2). After nonspecific staining was removed with phosphate-buffered saline, alizarin red staining was visualized with a CanoScan 4400F (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Alizarin red-stained cells were dissolved with 10% cetylpyridinium (Sigma-Aldrich), and absorbance of the extracted solution was measured at 562 nm for quantification.

4.3. Adipocyte Differentiation

Primary osteoblast precursor cells were cultured in adipogenic medium containing insulin (1 µg/mL), dexamethasone (0.1 µM), rosiglitazone (1 µM), and 3-isobytyl-1-methylxanthine (0.5 mM) for two days. Cells were further cultured in adipogenic medium containing insulin (1 µg/mL) for six to nine days. Cultured cells were fixed with 3.7% formalin and stained with Oil Red-O solution.

4.4. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed as previously described [33,34]. Each analysis was performed in triplicate with a Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using SYBR green mixture (Qiagen). Target gene expression was normalized to the levels of an endogenous control, i.e., glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh). The relative quantitative value of each target gene compared to the calibrator for that target was expressed as 2−(Ct−Cc), wherein Ct and Cc represent the mean threshold cycle differences after normalization to Gapdh. The relative expression levels of samples are presented on a semi-log scale. The following oligonucleotide primers were used for real-time PCR: Gapdh, 5′-TGACCACAGTCCATGCCATCACTG-3′ and 5′-CAGGAGACAACCTGGTCCTCAGTG-3′; Runx2, 5′-CCCAGCCACCTTTACCTACA-3′ and 5′-CAGCGTCAACACCATCATTC-3′; Alp, 5′-CAAGGATATCGACGTGATCATG-3′ and 5′-GTCAGTCAGGTTGTTCCGATTC-3′; BSP, 5′-GGAAGAGGAGACTTCAAACGAAG-3′ and 5′-CATCCACTTCTGCTTCTTCGTTC-3′; C/EBPα, 5′-AAGAAGTCGGTGGACAAGAACAG-3′ and 5′-TGCGCACCGCGATGT-3′; PPARγ, 5′-TCCAGCATTTCTGCTCCACA-3′ and 5′-ACAGACTCGGCACTCAATGG-3′; aP2, 5′-AAATCACCGCAGACGACA-3′ and 5′-CACATTCCACCACCAGCT-3′.

4.5. Luciferase Assay

Mouse myoblasts C2C12 cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well one day before transfection. The Runx2 reporter plasmid was transfected into C2C12 cells using Attractene according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were treated with vehicle or 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M) for two days. Luciferase activity was measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.6. Retroviral Gene Transduction

The retrovirus packaging cell line Plat-E was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, puromycin (1 µg/mL), and blasticidin (10 µg/mL). To obtain viral supernatants, retroviral vectors were transfected into Plat-E using FuGENE 6 (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Viral supernatants were collected from culture medium at 48 h after transfection. Osteoblasts were infected with the retroviruses in the presence of 10 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 h.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

The downregulation of Runx2 mediated by 1,25(OH)2D3 in osteoblasts stimulates the transdifferentiation of osteoblasts to adipocytes, and this may partially contribute to decreased bone mass by decreasing bone formation and increasing bone resorption.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Program (NRF-2014R1A2A2A01003966, NRF-2014R1A1A2009740, NRF-2015R1C1A1A02037671) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning.

Abbreviations

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| BSP | Bone sialoprotein |

| CEBP-α | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ |

| PPi | Pyrophosphate |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

| VDRE | Vitamin D response element |

Author Contributions

Jung Ha Kim and Nacksung Kim conceived and designed the experiments; Semun Seong and Byung-Chul Jeong performed the experiments; Kabsun Kim and Inyoung Kim analyzed the data; Jung Ha Kim and Nacksung Kim wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Walsh M.C., Kim N., Kadono Y., Rho J., Lee S.Y., Lorenzo J., Choi Y. Osteoimmunology: Interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:33–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappariello A., Maurizi A., Veeriah V., Teti A. The great beauty of the osteoclast. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;558:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J.H., Kim N. Signaling pathways in osteoclast differentiation. Chonnam Med. J. 2016;52:12–17. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2016.52.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouillon R., Suda T. Vitamin D: Calcium and bone homeostasis during evolution. BoneKEy Rep. 2014;3:480. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lips P., van Schoor N.M. The effect of vitamin D on bone and osteoporosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;25:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lips P. Vitamin D physiology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006;92:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beresford J.N., Gallagher J.A., Russell R.G. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and human bone-derived cells in vitro: Effects on alkaline phosphatase, type I collagen and proliferation. Endocrinology. 1986;119:1776–1785. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-4-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F.P., Lee N., Wang K.C., Soong Y.K., Huang K.E. Effect of estrogen and 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 on the activity and growth of human primary osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Fertil. Steril. 2002;77:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Driel M., Koedam M., Buurman C.J., Hewison M., Chiba H., Uitterlinden A.G., Pols H.A., van Leeuwen J.P. Evidence for auto/paracrine actions of vitamin D in bone: 1α-Hydroxylase expression and activity in human bone cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:2417–2419. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6374fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R., Ducy P., Karsenty G. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits osteocalcin expression in mouse through an indirect mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:110–116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieben L., Masuyama R., Torrekens S., Van Looveren R., Schrooten J., Baatsen P., Lafage-Proust M.H., Dresselaers T., Feng J.Q., Bonewald L.F., et al. Normocalcemia is maintained in mice under conditions of calcium malabsorption by vitamin D-induced inhibition of bone mineralization. J. Clin. Investig. 2012;122:1803–1815. doi: 10.1172/JCI45890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komori T. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by transcription factors. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;99:1233–1239. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komori T., Yagi H., Nomura S., Yamaguchi A., Sasaki K., Deguchi K., Shimizu Y., Bronson R.T., Gao Y.H., Inada M., et al. Targeted disruption of CBFA1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otto F., Thornell A.P., Crompton T., Denzel A., Gilmour K.C., Rosewell I.R., Stamp G.W., Beddington R.S., Mundlos S., Olsen B.R., et al. CBFA1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell. 1997;89:765–771. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Z., Rosen E.D., Brun R., Hauser S., Adelmant G., Troy A.E., McKeon C., Darlington G.J., Spiegelman B.M. Cross-regulation of C/EBP α and PPAR γ controls the transcriptional pathway of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:151–158. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savopoulos C., Dokos C., Kaiafa G., Hatzitolios A. Adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis: Trans-differentiation in the pathophysiology of bone disorders. Hippokratia. 2011;15:18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan K.J., Daniel Z.C., Craggs L.J., Parr T., Brameld J.M. Dose-dependent effects of vitamin D on transdifferentiation of skeletal muscle cells to adipose cells. J. Endocrinol. 2013;217:45–58. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drissi H., Pouliot A., Koolloos C., Stein J.L., Lian J.B., Stein G.S., van Wijnen A.J. 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 suppresses the bone-related Runx2/CBFA1 gene promoter. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;274:323–333. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han M.S., Che X., Cho G.H., Park H.R., Lim K.E., Park N.R., Jin J.S., Jung Y.K., Jeong J.H., Lee I.K., et al. Functional cooperation between vitamin D receptor and Runx2 in vitamin D-induced vascular calcification. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamei Y., Kawada T., Kazuki R., Ono T., Kato S., Sugimoto E. Vitamin D receptor gene expression is up-regulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;193:948–955. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawada T., Kamei Y., Sugimoto E. The possibility of active form of vitamins A and D as suppressors on adipocyte development via ligand-dependent transcriptional regulators. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1996;20:S52–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato M., Hiragun A. Demonstration of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor-like molecule in ST 13 and 3T3 L1 preadipocytes and its inhibitory effects on preadipocyte differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 1988;135:545–550. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041350326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nimitphong H., Holick M.F., Fried S.K., Lee M.J. 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 promote the differentiation of human subcutaneous preadipocytes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellows C.G., Wang Y.H., Heersche J.N., Aubin J.E. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates adipocyte differentiation in cultures of fetal rat calvaria cells: Comparison with the effects of dexamethasone. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2221–2229. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.5.8156925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komori T. Requisite roles of Runx2 and CBFB in skeletal development. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2003;21:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00774-002-0408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enomoto H., Furuichi T., Zanma A., Yamana K., Yoshida C., Sumitani S., Yamamoto H., Enomoto-Iwamoto M., Iwamoto M., Komori T. Runx2 deficiency in chondrocytes causes adipogenic changes in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:417–425. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gori F., Thomas T., Hicok K.C., Spelsberg T.C., Riggs B.L. Differentiation of human marrow stromal precursor cells: Bone morphogenetic protein-2 increases OSF2/CBFA1, enhances osteoblast commitment, and inhibits late adipocyte maturation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999;14:1522–1535. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.9.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori K., Suzuki K., Hozumi A., Goto H., Tomita M., Koseki H., Yamashita S., Osaki M. Potentiation of osteoclastogenesis by adipogenic conversion of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed. Res. 2014;35:153–159. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.35.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda S., Yoshizawa T., Nagai Y., Yamato H., Fukumoto S., Sekine K., Kato S., Matsumoto T., Fujita T. Stimulation of osteoclast formation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D requires its binding to vitamin D receptor (VDR) in osteoblastic cells: Studies using vdr knockout mice. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1005–1008. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitazawa R., Kitazawa S. Vitamin D3 augments osteoclastogenesis via vitamin D-responsive element of mouse rankl gene promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;290:650–655. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang B.M., Eslick G.D., Nowson C., Smith C., Bensoussan A. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders K.M., Stuart A.L., Williamson E.J., Simpson J.A., Kotowicz M.A., Young D., Nicholson G.C. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1815–1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J.H., Kim K., Kim I., Seong S., Kim N. NRROS negatively regulates osteoclast differentiation by inhibiting RANKL-mediated NF-κB and reactive oxygen species pathways. Mol. Cell. 2015;38:904–910. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim K., Kim J.H., Kim I., Lee J., Seong S., Park Y.W., Kim N. MicroRNA-26a regulates RANKL-induced osteoclast formation. Mol. Cell. 2015;38:75–80. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]