Abstract

Cold heart protection via cardioplegia administration, limits the amount of oxygen demand. Systemic normothermia with warm cardioplegia was introduced due to the abundance of detrimental effects of hypothermia. A temperature of 32–33°C in combination with tepid blood cardioplegia of the same temperature appears to be protective enough for both; heart and brain. Reduction of nitric oxide (NO) concentration is in part responsible for myocardial injury after the cardioplegic cardiac arrest. Restoration of NO balance with exogenous NO supplementation has been shown useful to prevent inflammation and apoptosis. In this article, we discuss the “deleterious” effects of the oxidative stress of the extracorporeal circulation and the up-to-date theories of “ideal” myocardial protection.

Keywords: Cardioplegia, Free radicals, Ischemia-reperfusion syndrome, Myocardial protection, Oxidative stress, Reperfusion injury

INTRODUCTION

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) triggers deleterious effects that may potentially cause dysfunction in almost every organ such as kidney, liver, lungs, central nervous system, and cardiovascular system.[1] Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is considered as the main etiologic factor causing heart damage.[2] It is usually a result of temporary cross clamping myocardial ischemia and the subsequent reperfusion injury after the restoration of heart perfusion.[1]

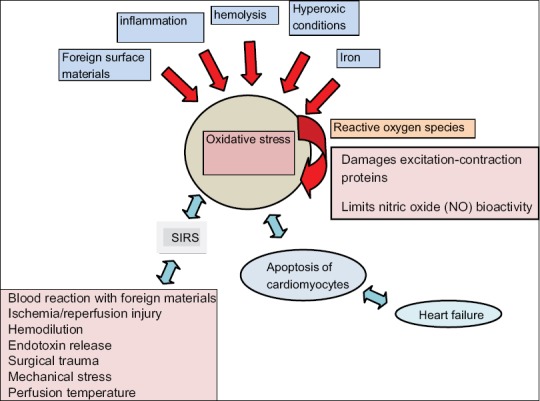

Figure 1 shows the factors implicated in oxidative stress and their mode of action.

Figure 1.

Factors implicated in oxidative stress in cardiopulmonary by-pass. NO: Nitric oxide, SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

These factors induce oxidative stress via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).[3] ROS, detected as radical adducts or lipid peroxides in coronary venous blood after aortic clamp release, can cause reperfusion injury and affect myocardial recovery.[4,5] Cardioplegia used in CPB also participates in cardiac injury via several ways such as damaging excitation-contraction proteins and limits nitric oxide (NO) bioactivity.[6]

Myocardial protection during CPB is mostly consisted of two components: Hypothermia[7] to diminish oxygen demand, and potassium inducing electromechanical cardiac arrest.[8] The combination of the aforementioned methods has given just a few benefits, and it has been long proved that hypothermia has a detrimental impact on enzymatic and biochemical systems. Normothermia, although used by just a few surgical teams, limits the risk of postoperative complications.[9] As a consequence, there is a continuing debate as to which is the most secure method for myocardial protection if any. We will try to address this important issue.

DELETERIOUS CARDIOPULMONARY BYPASS-INDUCED EFFECTS

SIRS is induced by CPB via the activation of neutrophils and endothelial cells,[10] as well as inflammatory mediators, such as Factor XII, kallikrein-kinin, fibrinolytic, and complement systems and cytokines.[11,12] The pro-inflammatory cytokines-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8, and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 are also increased.[13,14]

Characteristic symptoms of SIRS are fever, elevated white blood cells, respiratory insufficiency, elevated heart rate, and a PaCO2 <32 mmHg. Figure 1 shows the main factors responsible for the initiation of the SIRS process.[15] Moreover, inflammation, infarction, and contractile impairment resulting in cardiac dysfunction can be the deleterious effects of reperfusion of the ischemic heart after CPB.[16] Apoptosis of cardiomyocytes can also be induced by ischemia and reperfusion[17,18] leading to ventricular dysfunction and subsequent heart failure[19] due to significant loss of myocardial tissue.[20] Myocardial temperature and flow deprivation time are the major factors that indicate whether CPB related myocardial ischemia-reperfusion results in irreversible (myocardial necrosis) or reversible (myocardial stunning) injury.[21] Cardiac-specific troponin I (cTnI) and creatine kinase MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) are the established markers of myocardial necrosis.[22] Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) have been shown to have elevated cTnI levels as a result of myocardial damage. Handling the myocardium, placing sutures for cannulation and dissecting the myocardium to reveal a coronary vessel also lead to cTnI augmentation.[23,24] cTnI elevation has been correlated with the quality of myocardial protection.[23] Arterial values over 15 μg/l for cTnI and 30 μg/l for CK-MB demonstrates perioperative myocardial infarction (MI),[25] although 25% of post-CABG patients have a CK-MB mass value >35.8 μg/l without experiencing any ischemic complications.[26] Carrier et al.[27] suggested that postoperative MI is characterized by a value of cTnI in the serum over 39 ng/mL at 24 h postoperatively. However, clinical studies doubt if there is any significant correlation between necrosis and contractile function.[28,29,30] Some studies[30,31,32] demonstrate very close correlation among cardiac enzymes release, recovery of oxidative metabolism, and ischemic time while others[25,33] show that there is no such correlation. They conclude that the duration of cardioplegic cardiac arrest (CCA) is not the principal factor of perioperative myocardial damage. An atherosclerosis both quality and route of delivery of cardioplegia and temperature are most likely to be responsible for the myocardial injury. Myocardial stunning seems to be induced by oxidative stress during reperfusion.[31] Activation of neutrophils,[34] poor perfusion of the peripheral tissues and the high oxygen tension used during CPB[35,36] are responsible for both coronary and systemic oxygen free radical generation after cardioplegia administration.[1,31] Moreover, peripheral alkyl- and alkoxyl- radicals appear to be released continuously during the cross-clamp period apart from the reperfusion time of the ischemic heart.[1] The existence of a correlation between the severity of oxidative stress and postoperative recovery of cardiac function is also controversial.[31] During reperfusion, heart constitutes a source of ROS production and is also a target of systemic ROS generated by activated cells.[37,38,39] ROS including alkyl- and alkoxyl- radicals could exacerbate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, as they are able to participate in cellular injury, affecting myocardial contractility.[40,41,42,43,44] Ferrari et al.[45] among other investigators,[46,47] support the existence of a relationship between oxidative stress and myocardial dysfunction. But, others[31,33,48] did not find such correlation. Karua et al.[31] suggest that CPB-related oxidative stress does not influence the postoperative myocardial recovery in CABG patients with good preoperative left ventricular function. Finally, a decrease of endogenous NO generation, catalyzed by inducible NO synthase (iNOS), is possible after CPB due to cardioplegia-induced cardiac arrest.[6] Temporary endothelial cell dysfunction results in a lack of NO sufficiency during the reperfusion period of CPB. Subsequently, vasospasm takes place due to low levels of NO.[49] NO appears to participate in the nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) system,[16] in the evolution of cardiovascular injury[50] and in the anti-inflammatory properties of the vascular endothelium.[51] Lower concentrations of bioavailable NO leads to chronic activation of NF-kB, which is associated with inflammation.[52] NF-kB stimulates the immune system, particularly B cells, and macrophages. Cytokines and oxygen radicals activate the aforementioned cells resulting in NF-kB translocation. Alterations in NF-kB system are determinants for the deleterious effects of CCA during CPB.[6] Yeh et al.[6] proved that CCA under CPB induced a reduction of myocardial NO concentration with a subsequent increase of NF-kB translocation. A similar change was demonstrated concerning the expression of NF-kB-mediated genes.

MYOCARDIAL PROTECTION

The basic role of myocardial protection during cardiac surgery is a balance between a bloodless, motionless operating field and the maintenance of the myocardial function.[9] Hypothermia or normothermia can be both used for CPB.[2] Provided that the myocardium constitutes a source of cytokines,[53,54] both perfusion temperatures of CPB and cardioplegia type are able to affect the generation of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6 and TNF-α.[2] Cardioplegia induces electromechanical arrest. Therefore, myocardial metabolism is reduced, and intermittent ischemia is bearable.[55,56] The optimal choice of cardioplegia, though, is controversial. In the UK, 56% of surgeons performing on-pump CABG prefer cold blood cardioplegia, 14% of them prefer warm blood cardioplegia and 14% use crystalloid cardioplegia, whereas retrograde infusion is the method of choice for 21% of them. The rest 16% of surgeons apply cross-clamp fibrillation, avoiding any type of cardioplegia.[57] A retrospective review[58] studied 22 papers with equal to or over 50 patients each with respect to types of cardioplegia, Guru et al.[59] reported a correlation of blood cardioplegia with significantly lower CK-MB levels and significantly fewer cases of low output syndrome in their meta-analysis of 34 randomized trials. Øvrum et al.[60] demonstrated no clinical differences among 1440 patients undergoing either antegrade cold blood or crystalloid cardioplegia, whereas Martin et al.[61] never completed their 1001 patients study comparing warm blood to cold crystalloid cardioplegia because of a high incidence of neurological complications associated with the former. Ten of the rest 19 studies showed that blood cardioplegia was superior to crystalloid cardioplegia in terms of statistically significant clinical effects. Five of them also demonstrated the superiority of the former with regard to enzyme release.[58] Barra et al.[62] reported a linear correlation of the cold crystalloid antegrade cardioplegia with the perioperative MI risk, elevated by four times. Despite its efficacy in causing electromechanical arrest, hyperkalemic crystalloid cardioplegia is only partially cardioprotective.[63] Ventricular dysfunction after cardioplegia infusion is possible potentially due to postoperative cardiomyocyte apoptosis.[63,64]

Blood has a lot of superior properties that make its substance unique to be compared to crystalloid.[65] Retrograde cardioplegia has been proved to efficiently provide myocardial protection.[66] Nevertheless, it is not protective enough for the interventricular septum and the right ventricle[67] due to anatomical variations of the coronary vascular bed.[68] On the other hand, antegrade hyperkalemic warm blood infusion permits diastolic cardiac arrest and preserves high energy phosphate levels.[69] At the present time, potassium infusion, providing a nonbeating heart due to the electromechanical cardiac arrest caused, and hypothermia, providing low oxygen needs, are the axis of myocardial protection.[9]

Benefits gained by hypothermia

It was in the 1960s that hypothermic cardioplegia was firstly introduced. It showed the result of decreasing myocardial metabolism, which was determinant for myocardial protection against ischemia.[70] Systemic hypothermia leads to hypothermia of the heart, as well as to repression of myocardial oxygen consumption.[71] When the myocardial temperature is low its metabolism tends to be low as well.[72,73,74] In conclusion, the electromechanical arrest is responsible for a 90% reduction in oxygen consumption.[9] Although hypothermia further reduces myocardial oxygen consumption, it offers a minor additional benefit in the order of 7%.[55,75]

DELETERIOUS EFFECTS OF HYPOTHERMIA

Despite reducing metabolic activity, hypothermia induces many detrimental effects.[9,76] It has an adverse impact on the metabolic and functional recovery of the heart as a result of reduced mitochondrial respiration[77,78,79,80] and decreased the production of myocardial high energy phosphates.[79,80,81] It also affects various enzymatic systems, such as sodium, potassium, and calcium adenylpyrophosphatase, altering the ionic composition of the cell and water homeostasis.[9,77,78,79,80] High arterial partial pressures (PaO2) and hypothermia make their control difficult leading to free radical generation damaging cellular membranes during reperfusion.[82] Paralysis of the diaphragm may be also induced by heart cooling methods.[83] Oxygen delivery to tissues is decreased due to an increase in hemoglobin affinity for oxygen[9,84] and due to an hemodilution-related decrease of blood oxygen-carrying capacity.[76] Furthermore, hypothermia leads to metabolic acidosis, increased plasma viscosity, reduced erythrocyte deformability, and subsequently lower flow through the micro-capillaries.[9] Cerebral blood flow is also decreased because of temperature lowering.[76] In addition, systemic vascular resistance, the so-called cardiac afterload, is increased due to elevated serum norepinephrine concentrations caused by hypothermia.[85] Hypothermia-induced vascular spasm also impedes blood supply.[9] According to Lahorra et al.,[86] cold cardioplegia combined with heart cooling leads to increased intracellular calcium, increased energy consumption, raised left intraventricular pressures, and increased coronary resistance. Inflammation is just delayed by hypothermia but not stopped.[87] However, in spite of elevated inflammatory cytokines levels, which are able to induce iNOS activity, hypothermia appears to be associated with decreased NO generation at least until 24 h after the end of CPB.[2,88]

BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF NORMOTHERMIA WITH WARM CARDIOPLEGIA

As a result of the aforementioned mechanisms, continuous normothermic blood cardioplegia has been introduced.[89,90] Lichtenstein et al.,[91] studying 720 patients who underwent CABG under normothermia, showed that normothermic electromechanical arrest was well tolerated for over 15 min by the myocardium. Normothermic myocardial protection is achieved by the continuous administration of hyperkalemic normothermic blood during the aortic cross-clamp time.[92] According to Lichtenstein et al.,[89,90] continuous hyperkalemic blood infusion preserving cardiac arrest and providing oxygen for the normothermic myocardium offers adequate myocardial protection throughout the cardiac surgery. Cardiac arrest is achieved by the infusion of blood cardioplegia containing high levels of potassium and it is preserved by low potassium blood cardioplegia infusion during the rest of the cross-clamp time. The latter is also useful as a continuous source of oxygen for the normothermic myocardium. However, during coronary anastomosis, the infusion of blood cardioplegia must be temporarily stopped, so as for a bloodless operating field to be provided.[92] Active continuous rewarming is also necessary to achieve systemic normothermia, meaning a temperature equal to 37°C, as the body temperature lowers in the operating room. Either retrograde or antegrade warm blood cardioplegia can be used to achieve warm heart protection.[9] Lots of benefits are obtained by normothermia. Firstly, continuous warm blood administration provides a constant oxygen supply preserving aerobic metabolism. Better tissue oxygen transfer is also achieved thanks to the near normal hemoglobin affinity for oxygen, normal enzymatic activity, and normal erythrocyte deformability. Viscosity is also maintained by normothermia.[9] Furthermore, as the skin is warmed under normothermia, the adrenergic response is minimized, thus diminishing the afterload and elevating the cardiac index.[23] Additionally, the complications caused by high PaO2 are prevented using normothermia permitting the control of PaO2. Ischemia-reperfusion injury from free radicals is avoided as aerobic cardioplegic perfusion takes place. Neither intracellular pH nor the acid-basic balance is affected resulting in the better gas transfer. Ionic status and water homeostasis are also preserved thanks to the normal supply of adenosine triphosphate to ion pumps.[9] Moreover, spontaneous defibrillation after cross-clamp release is more possible, and MI tends to be less common when CPB is performed under warm heart protection.[93] Finally, normothermia may decrease the CPB-related inflammatory response.[94] Apart from Lichtenstein et al. who highlighted the clinical benefit of normothermia, particularly in prolonged aortic cross-clamp time (6.5 h).[91] Bert et al.[95] also reported data favouring normothermia against hypothermia with regard to postoperative clinical outcomes. Lots of other studies[96,97,98,99,100,101] demonstrate a superiority of systemic and myocardial temperature preservation. Tavares-Murta et al.[2] compared 10 patients who were submitted to CPB under hypothermia (29-31°C) with crystalloid cardioplegia (HC group) to 10 other patients who received normothermic (36.5-37°C) CPB with blood cardioplegia (NB group). All of them presented elevated cytokine levels, but this change took place earlier and for a longer time in HC group. The same group had significantly higher peak levels of IL-6, which were significantly correlated (P < 0.01) with peak levels of IL-8. NO generation was also decreased in HC group. Moreover, two groups of patients were compared by Bical et al.[102] using warm blood protection in Group I and cold blood protection in Group II with intermittent antegrade cardioplegia in both groups. They reported higher levels of coronary sinus lactate at cross-clamp removal in Group I, while more myoglobin was generated after reperfusion in Group II. Troponin I levels were also higher in Group II. Thus, warm cardioplegia protection was better than cold.

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS OF TEPID (32°C) CARDIOPLEGIA

The safe duration of a cardioplegia break under normothermia is unclear, so tepid cardioplegia constitutes an alternative choice.[101,103] It has the ability to protect the myocardium even during cardioplegia interruptions apart from effectively promoting aerobic metabolism.[70] Comparing this type of cardioplegia with warm blood cardioplegia, the myocardial oxygen consumption is similar, while anaerobic lactate and acid washout is less during the former.[104] Furthermore, during lukewarm (tepid) blood cardioplegia more glucose and oxygen are consumed by the myocardium, whereas less lactate is generated than during cold cardioplegia.[70] Moreover, although warmth protects the heart, it negatively affects the brain.[105] Warm blood cardioplegia is commonly used under systemic normothermia, which raises the hazard of cardiac surgery-associated neurological disorders.[70] Hvass and Depoix[106] demonstrated no increase in neurological disorders at 37°C. In a study published in Lancet in 1994,[107] exanimating 1732 patients operated under lower systemic temperature, found no significant difference neither concerning the myocardium nor the incidence of neurological disorders. Martin et al.[61] and Guyton et al.[108] comparing 493 patients who underwent CABG under warm blood cardioplegia and a systemic temperature of 35°C with a series of 508 patients who were operated under cold cardioplegia (8°C) and a systemic temperature of 28°C found similar results with regard to perioperative infarction, mortality, and intra-aortic counterpulsation requirement, respectively. Nevertheless, as far as neurological complications were concerned, they were significantly more frequent in the normothermic group (4.5%) than in the cold one (1.4%). A systemic temperature of 32–33°C combined with lukewarm blood cardioplegia seems to be more protective for the cerebrum overcoming the hazard of neurologic complications under normothermic conditions.[9,70,109] Apart from not influencing the neurologic system and preserving physiological and enzymatic systems, tepid (32°C) protection is superior to cold protection in terms of reduced ventricular rhythm disorders, spontaneous defibrillation and blood loss.[91,99,102] Moreover, prolongation of the aortic cross-clamp time without worsening operative mortality and morbidity can be achieved via continuous retrograde lukewarm blood cardioplegia under systemic normothermia.[68] Less myocardial injury and better functional recovery of the left ventricle constitute additional benefits gained by tepid cardioplegia.[70] Continuous tepid blood cardioplegia is advantageous in preventing cardiomyocytes from apoptosis and maintaining coronary endothelium integrity. Myocardial injury induced by cardiac arrest and endothelial dysfunction due to reperfusion injury are minimized by this type of cardioplegia thanks to adequate supply of nutrients and oxygen and the concomitant washout of all the metabolic waste.[63] Engelman et al.[110] compared three groups undergoing coronary surgery: Group I - cold (20°C systemic temperature, 8–10°C blood cardioplegia), Group II - tepid (32°C systemic temperature, 32°C blood cardioplegia), and Group III - warm (37°C systemic temperature, 37°C blood cardioplegia). No death was noticed in either of these groups. Group I was associated with a more prolonged hospital stay and a postoperative CK-MB increase. Neurological complications were significantly lower in the tepid group (2%) against the 18.9% percentage of the cold group and 9.3% in one of the warm group. In Badak et al.’s study,[70] comparing tepid with cold blood cardioplegia during CABG, 30 patients were randomized into two groups of 15 patients (a tepid and a cold one). The tepid group was characterized by greater myocardial oxygen extraction, greater oxygen and glucose consumption, and lower lactate generation than the cold one. In the early post-CPB period, the left ventricular stroke work index was also greater in the tepid group and the early postoperative CK-MB levels at 6, 12, and 24 h were significantly lower than in the cold group. Finally, significantly more patients submitted to cold heart protection needed defibrillation compared to those undergone tepid heart protection. In a recent review study conducted by Zeng et al. in 2014,[111] has been showed that cold blood cardioplegia reduces perioperative MI when compared with cold crystalloid cardioplegia. No differences in the overall incidence rates of spontaneous sinus rhythm, mortality (within 30 days), atrial fibrillation, or stroke were observed.

ROLE OF NITRIC OXIDE IN MYOCARDIAL PROTECTION

NO participates in several ways in the vascular bed.[112] It causes vasodilation on vascular smooth muscles via activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase and subsequent cyclic guanosine monophosphate formation. Adhesion, inflammation, and proliferation of endothelial cells are also inhibited by NO. Therefore, exogenous NO supplementation also plays a significant role in myocardial protection by restoring NO concentration diminished by CCA under CPB.[111] Multiple benefits can be obtained by restoration of NO concentration including repression of the NF-kB translocation and reduction of the generation of inflammatory cytokines.[6] NO donor throughout reperfusion limits myocardial injury and the inflammatory response (lower IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α levels).[113] Additionally, NO donor prevents the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and preserves their contractile function.[6] Lower levels of markers of myocardial damage are also noticed after the infusion of blood cardioplegia enriched with the substrate for NO synthesis L-arginine.[111] Experiments have recently been conducted to investigate the cardioprotective role of oxytocin,[113] “h ANP shot” using human atrial natriuretic peptide[114] and the use of statin and angiotensin receptor blocker.[115] Cardioprotection and lung protection is also the “cornerstone” for a successful open heart intervention.[116]

CONCLUSIONS

It is obvious that CPB itself, as well as CCA under CPB have some detrimental impacts on the myocardium. However, which is the ideal myocardial protection? In spite of the cardioprotective properties of cold heart protection thanks to limiting the needs in oxygen, systemic normothermia with warm cardioplegia was introduced due to the abundance of detrimental effects of hypothermia. Nevertheless, although normothermia is the best choice for heart protection, it is not for the brain. A temperature of 32–33°C in combination with tepid blood cardioplegia of the same temperature appears to be protective enough for both of them making the procedure less invasive and permitting cost reduction too. In addition, since the reduction of NO concentration is in part responsible for myocardial injury after CCA under CPB, the restoration of NO balance with exogenous NO supplementation is ultimately useful to prevent inflammation and apoptosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clermont G, Vergely C, Jazayeri S, Lahet JJ, Goudeau JJ, Lecour S, et al. Systemic free radical activation is a major event involved in myocardial oxidative stress related to cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:80–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200201000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavares-Murta BM, Cordeiro AO, Murta EF, Cunha Fde Q, Bisinotto FM. Effect of myocardial protection and perfusion temperature on production of cytokines and nitric oxide during cardiopulmonary bypass. Acta Cir Bras. 2007;22:243–50. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502007000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg K, Haaverstad R, Astudillo R, Bjӧrngaard M, Skarra S, Wiseth R, et al. Oxidative stress during coronary artery bypass operations: Importance of surgical trauma and drug treatment. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2006;40:291–7. doi: 10.1080/14017430600855077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulus AT, Aksoyek A, Ozkan M, Katircioglu SF, Basu S. Cardiopulmonary bypass as a cause of free radical-induced oxidative stress and enhanced blood-borne isoprostanes in humans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:911–7. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goudeau JJ, Clermont G, Guillery O, Lemaire-Ewing S, Musat A, Vernet M, et al. In high-risk patients, combination of antiinflammatory procedures during cardiopulmonary bypass can reduce incidences of inflammation and oxidative stress. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;49:39–45. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31802c0cd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh CH, Chen TP, Lee CH, Wu YC, Lin YM, Lin PJ. Cardioplegia-induced cardiac arrest under cardiopulmonary bypass decreased nitric oxide production which induced cardiomyocytic apoptosis via nuclear factor kappa B activation. Shock. 2007;27:422–8. doi: 10.1097/01.shk0000239761.13206.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigelow WG, Lindsay WK, Greenwood WF. Hypothermia; its possible role in cardiac surgery: An investigation of factors governing survival in dogs at low body temperatures. Ann Surg. 1950;132:849–66. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195011000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melrose DG, Dieger DB, Bentall HH, Belzer FO. Elective cardiac arrest: Preliminary communications. Lancet. 1955;2:21–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaillard D, Bical O, Paumier D, Trivin F. A review of myocardial normothermia: Its theoretical basis and the potential clinical benefits in cardiac surgery. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:198–203. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(00)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faymonville ME, Pincemail J, Duchateau J, Paulus JM, Adam A, Deby-Dupont G, et al. Myeloperoxidase and elastase as markers of leukocyte activation during cardiopulmonary bypass in humans. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;102:309–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chenoweth DE, Cooper SW, Hugli TE, Stewart RW, Blackstone EH, Kirklin JW. Complement activation during cardiopulmonary bypass: Evidence for generation of C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:497–503. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102263040901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller BE, Levy JH. The inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1997;11:355–66. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(97)90106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawamura T, Nara N, Kadosaki M, Inada K, Endo S. Prostaglandin E1 reduces myocardial reperfusion injury by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines production during cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2201–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volk T, Schmutzler M, Engelhardt L, Döcke WD, Volk HD, Konertz W, et al. Influence of aminosteroid and glucocorticoid treatment on inflammation and immune function during cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2137–42. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy JH, Tanaka KA. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:715–20. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Entman ML, Michael L, Rossen RD, Dreyer WJ, Anderson DC, Taylor AA, et al. Inflammation in the course of early myocardial ischemia. FASEB J. 1991;5:2529–37. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.11.1868978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buerke M, Murohara T, Skurk C, Nuss C, Tomaselli K, Lefer AM. Cardioprotective effect of insulin-like growth factor I in myocardial ischemia followed by reperfusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8031–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb RA, Burleson KO, Kloner RA, Babior BM, Engler RL. Reperfusion injury induces apoptosis in rabbit cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1621–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI117504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Didenko VV, Wang X, Yang L, Hornsby PJ. Expression of p21(WAF1/CIP1/SDI1) and p53 in apoptotic cells in the adrenal cortex and induction by ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1723–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI118599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Henriksen K, Parvinen M, Voipio-Pulkki LM. Apoptosis in human acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;95:320–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolli R, Marbán E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial stunning. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:609–34. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benoit MO, Paris M, Silleran J, Fiemeyer A, Moatti N. Cardiac troponin I: Its contribution to the diagnosis of perioperative myocardial infarction and various complications of cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1880–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nesher N, Zisman E, Wolf T, Sharony R, Bolotin G, David M, et al. Strict thermoregulation attenuates myocardial injury during coronary artery bypass graft surgery as reflected by reduced levels of cardiac-specific troponin I. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:328–35. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnefoy E, Filley S, Kirkorian G, Guidollet J, Roriz R, Robin J, et al. Troponin I, troponin T, or creatine kinase-MB to detect perioperative myocardial damage after coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest. 1998;114:482–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alyanakian MA, Dehoux M, Chatel D, Seguret C, Desmonts JM, Durand G, et al. Cardiac troponin I in diagnosis of perioperative myocardial infarction after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998;12:288–94. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(98)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmvang L, Jurlander B, Rasmussen C, Thiis JJ, Grande P, Clemmensen P. Use of biochemical markers of infarction for diagnosing perioperative myocardial infarction and early graft occlusion after coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest. 2002;121:103–11. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrier M, Pellerin M, Perrault LP, Solymoss BC, Pelletier LC. Troponin levels in patients with myocardial infarction after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:435–40. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang PP, Sussman MS, Conte JV, Grega MA, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, et al. Postoperative ventricular function and cardiac enzymes after on-pump versus off-pump CABG surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1107–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwinecki P, Jemielity M, Czepczynski R, Baszko A, Ruchala M, Sowinski J, et al. Nuclear imaging techniques in the assessment of myocardial perfusion and function after CABG: Does it correlate with CK-MB elevation? Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2003;6:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koh TW, Hooper J, Kemp M, Ferdinand FD, Gibson DG, Pepper JR. Intraoperative release of troponin T in coronary venous and arterial blood and its relation to recovery of left ventricular function and oxidative metabolism following coronary artery surgery. Heart. 1998;80:341–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karua I, Loita R, Paapstel A, Kairane C, Zilmer M, Starkopf J. Early postoperative function of the heart after coronary artery bypass grafting is not predicted by myocardial necrosis and glutathione-associated oxidative stress. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;359:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raman JS, Bellomo R, Hayhoe M, Tsamitros M, Buxton BF. Metabolic changes and myocardial injury during cardioplegia: A pilot study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1566–71. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biagioli B, Borrelli E, Maccherini M, Bellomo G, Lisi G, Giomarelli P, et al. Reduction of oxidative stress does not affect recovery of myocardial function: Warm continuous versus cold intermittent blood cardioplegia. Heart. 1997;77:465–73. doi: 10.1136/hrt.77.5.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morse D, Adams D, Maganani B. Platelets and neutrophil activation during cardiac surgical procedures: Impact of cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:691–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ihnken K, Winkler A, Schlensak C, Sarai K, Neidhart G, Unkelbach U, et al. Normoxic cardiopulmonary bypass reduces oxidative myocardial damage and nitric oxide during cardiac operations in the adult. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:327–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(98)70134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight PR, Holm BA. The three components of hyperoxia. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:3–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhote-Burger P, Vuilleminot A, Lecompte T, Pasquier C, Bara L, Julia P, et al. Neutrophil degranulation related to the reperfusion of ischemic human heart during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;25:S124–9. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199500252-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen PR, Stawski G. Neutrophil mediated damage to isolated myocytes after anoxia and reoxygenation. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:565–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen PR. Role of neutrophils in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1995;91:1872–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hearse DJ, Bolli R. Reperfusion induced injury: Manifestations, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:101–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolli R. Mechanism of myocardial “stunning”. Circulation. 1990;82:723–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.3.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Opie LH. Reperfusion injury and its pharmacologic modification. Circulation. 1989;80:1049–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XY, McCay PB, Zughaib M, Jeroudi MO, Triana JF, Bolli R. Demonstration of free radical generation in the “stunned” myocardium in the conscious dog and identification of major differences between conscious and open-chest dogs. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1025–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI116608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradamante S, Monti E, Paracchini L, Lazzarini E, Piccinini F. Protective activity of the spin trap tert-butyl-alpha-phenyl nitrone (PBN) in reperfused rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1992;24:375–86. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)93192-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrari R, Alfieri O, Curello S, Ceconi C, Cargnoni A, Marzollo P, et al. Occurrence of oxidative stress during reperfusion of the human heart. Circulation. 1990;81:201–11. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu ZK, Tarkka MR, Eloranta J, Pehkonen E, Kaukinen L, Honkonen EL, et al. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on myocardial protection in coronary artery bypass graft patients: Can the free radicals act as a trigger for ischemic preconditioning? Chest. 2001;119:1061–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.4.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Vecchi E, Pala MG, Di Credico G, Agape V, Paolini G, Bonini PA, et al. Relation between left ventricular function and oxidative stress in patients undergoing bypass surgery. Heart. 1998;79:242–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inselmann G, Köhler K, Lange V, Silber R, Nellessen U. Lipid peroxidation and cardiac troponin T release during routine cardiac surgery. Cardiology. 1998;89:124–9. doi: 10.1159/000006767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang WZ, Anderson G, Fleming JT, Peter FW, Franken RJ, Acland RD, et al. Lack of nitric oxide contributes to vasospasm during ischemia/reperfusion injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1099–108. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199704000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith EF, 3rd, Egan JW, Bugelski PJ, Hillegass LM, Hill DE, Griswold DE. Temporal relation between neutrophil accumulation and myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol. 1988;255(5 Pt 2):H1060–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.5.H1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kitamoto S, Egashira K, Kataoka C, Koyanagi M, Katoh M, Shimokawa H, et al. Increased activity of nuclear factor-kappaB participates in cardiovascular remodeling induced by chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in rats. Circulation. 2000;102:806–12. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Korn SH, Vos N, Guala AS, Wouters EF, et al. Nitric oxide represses inhibitory kappaB kinase through S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8945–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400588101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liebold A, Langhammer Th, Brünger F, Birnbaum DE. Cardiac interleukin-6 release and myocardial recovery after aortic crossclamping. Crystalloid versus blood cardioplegia. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1999;40:633–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Billia F, Carter K, Rao V, Gorczynski R, Feindel C, Ross HJ. Transforming growth factor-beta expression is significantly lower in hearts preserved with blood/insulin versus crystalloid cardioplegia. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:918–22. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buckberg GD, Brazier JR, Nelson RL, Goldstein SM, McConnell DH, Cooper N. Studies of the effects of hypothermia on regional myocardial blood flow and metabolism during cardiopulmonary bypass. I. The adequately perfused beating, fibrillating, and arrested heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landymore RW, Marble AE. Effect of hypothermia and cardioplegia on intramyocardial voltage and myocardial oxygen consumption. Can J Surg. 1990;33:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karthik S, Grayson AD, Oo AY, Fabri BM. A survey of current myocardial protection practices during coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:413–5. doi: 10.1308/147870804669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacob S, Kallikourdis A, Sellke F, Dunning J. Is blood cardioplegia superior to crystalloid cardioplegia? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:491–8. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.178343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guru V, Omura J, Alghamdi AA, Weisel R, Fremes S. Is blood superior to crystalloid cardioplegia?. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circulation. 2006;114(Suppl I):I. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Øvrum E, Tangen G, Tølløfsrud S, Øystese R, Ringdal MA, Istad R. Cold blood cardioplegia versus cold crystalloid cardioplegia: A prospective randomized study of 1440 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:860–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin TD, Craver JM, Gott JP, Weintraub WS, Ramsay J, Mora CT, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of retrograde warm blood cardioplegia: Myocardial benefit and neurologic threat. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:298–302. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)90987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barra JA, Bezon E, Mondine P, Resk A, Gilard M, Mansourati J, et al. Surgical angioplasty with exclusion of atheromatous plaques in case of diffuse disease of the left anterior descending artery: 2 years’ follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:509–14. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeh CH, Wang YC, Wu YC, Chu JJ, Lin PJ. Continuous tepid blood cardioplegia can preserve coronary endothelium and ameliorate the occurrence of cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Chest. 2003;123:1647–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.López JR, Jahangir R, Jahangir A, Shen WK, Terzic A. Potassium channel openers prevent potassium-induced calcium loading of cardiac cells: Possible implications in cardioplegia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:820–31. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Velez DA, Morris CD, Budde JM, Muraki S, Otto RN, Guyton RA, et al. All-blood (miniplegia) versus dilute cardioplegia in experimental surgical revascularization of evolving infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(12 Suppl 1):I296–302. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Menasché P, Subayi JB, Veyssié L, le Dref O, Chevret S, Piwnica A. Efficacy of coronary sinus cardioplegia in patients with complete coronary artery occlusions. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:418–23. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)90857-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crooke GA, Harris LH, Grossi EA, Baumann FG, Galloway AC, Colvin SB. Biventricular distrubution of cold blood cardioplegic solution administered by different retrograde techniques. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;102:631–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bezon E, Choplain JN, Khalifa AA, Numa H, Salley N, Barra JA. Continuous retrograde blood cardioplegia ensures prolonged aortic cross-clamping time without increasing the operative risk. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2006;5:403–7. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2006.131276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosenkranz ER, Vinten-Johansen J, Buckberg GD, Okamoto F, Edwards H, Bugyi H. Benefits of normothermic induction of blood cardioplegia in energy-depleted hearts, with maintenance of arrest by multidose cold blood cardioplegic infusions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;84:667–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Badak MI, Gurcun U, Discigil B, Boga M, Ozkisacik EA, Alayunt EA. Myocardium utilizes more oxygen and glucose during tepid blood cardioplegic infusion in arrested heart. Int Heart J. 2005;46:219–29. doi: 10.1536/ihj.46.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuniyoshi Y, Koja K, Miyagi K, Shimoji M, Uezu T, Yamashiro S, et al. Myocardial protective effect of hypothermia during extracorporeal circulation – By quantitative measurement of myocardial oxygen consumption. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;9:155–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grover FL, Fewel JG, Ghidoni JJ, Trinkle JK. Does lower systemic temperature enhance cardioplegic myocardial protection? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1981;81:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chitwood WR, Jr, Sink JD, Hill RC, Wechsler AS, Sabiston DC., Jr The effects of hypothermia on myocardial oxygen consumption and transmural coronary blood flow in the potassium-arrested heart. Ann Surg. 1979;190:106–16. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197907000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kao RL, Conti VR, Williams EH. Effect of temperature during potassium arrest on myocardial metabolism and function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;84:243–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hearse DJ, Stewart DA, Braimbridge MV. The additive protective effects of hypothermia and chemical cardioplegia during ischemic cardiac arrest in the rat. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;79:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grigore AM, Mathew J, Grocott HP, Reves JG, Blumenthal JA, White WD, et al. Prospective randomized trial of normothermic versus hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass on cognitive function after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1110–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200111000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bigelow W, Lindsay W, Harrison R, Gordon R, Greenwood W. Oxygen transport and utilization in dogs at low body temperatures. Am J Physiol. 1950;160:125–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1949.160.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dobbs WA, Engelman RM, Rousou JH, Pels MA, Alvarez JM. Residual metabolism of the hypothermic-arrested pig heart. J Surg Res. 1981;31:319–23. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(81)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lyons J, Raison J. A temperature-induced transition in mitochondrial oxidation: Contrasts between cold and warmblooded animals. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1970;37:405–11. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reissmann K, VanCitters R. Oxygen consumption and mechanical efficiency of the hypothermic heart. J Appl Physol. 1956;9:427–32. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1956.9.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teoh KH, Christakis GT, Weisel RD, Fremes SE, Mickle DA, Romaschin AD, et al. Accelerated myocardial metabolic recovery with terminal warm blood cardioplegia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;91:888–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Morita K, Ihnken K, Buckberg GD, Sherman MP, Young HH. Studies of hypoxemic/reoxygenation injury: Without aortic clamping. IX. Importance of avoiding perioperative hyperoxemia in the setting of previous cyanosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(4 Pt 2):1235–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(95)70010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maccherini M, Davoli G, Sani G, Rossi P, Giani S, Lisi G, et al. Warm heart surgery eliminates diaphragmatic paralysis. J Card Surg. 1995;10:257–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1995.tb00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Magovern GJ, Jr, Flaherty JT, Gott VL, Bulkley BH, Gardner TJ. Failure of blood cardioplegia to protect myocardium at lower temperatures. Circulation. 1982;66(2 Pt 2):I60–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frank SM, Higgins MS, Breslow MJ, Fleisher LA, Gorman RB, Sitzmann JV, et al. The catecholamine, cortisol, and hemodynamic responses to mild perioperative hypothermia. A randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:83–93. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199501000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lahorra JA, Torchiana DF, Tolis G Jr, Bashour CA, Hahn C, Titus JS, et al. Rapid cooling contracture with cold cardioplegia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1353–60. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Le Deist F, Menasché P, Kucharski C, Bel A, Piwnica A, Bloch G. Hypothermia during cardiopulmonary bypass delays but does not prevent neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion. A clinical study. Circulation. 1995;92(9 Suppl):II354–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gianetti J, Del Sarto P, Bevilacqua S, Vassalle C, De Filippis R, Kacila M, et al. Supplemental nitric oxide and its effect on myocardial injury and function in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2002.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lichtenstein SV, el Dalati H, Panos A, Slutsky AS. Long cross-clamp time with warm heart surgery. Lancet. 1989;1:1443. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lichtenstein SV, Ashe KA, el Dalati H, Cusimano RJ, Panos A, Slutsky AS. Warm heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101:269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lichtenstein SV, Abel JG, Fremes SE. Normothermic ischemia in coronary revascularization. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;793:328–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb33525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Landymore RW, Marble AE, Eng P, MacAulay MA, Fris J. Myocardial oxygen consumption and lactate production during antegrade warm blood cardioplegia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1992;6:372–6. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(92)90175-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kavanagh BP, Mazer CD, Panos A, Lichtenstein SV. Effect of warm heart surgery on perioperative management of patients undergoing urgent cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1992;6:127–31. doi: 10.1016/1053-0770(92)90185-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Daniel S. Review on the multifactorial aspects of bioincompatibility in CPB. Perfusion. 1996;11:246–55. doi: 10.1177/026765919601100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bert AA, Stearns GT, Feng W, Singh AK. Normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1997;11:91–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(97)90262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Youhana AY. Warm blood cardioplegia. Br Heart J. 1995;73:206–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.3.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chello M, Mastroroberto P, De Amicis V, Pantaleo D, Ascione R, Spampinato N. Intermittent warm blood cardioplegia preserves myocardial beta-adrenergic receptor function. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:683–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Calafiore AM, Teodori G, Bosco G, Di Giammarco G, Vitolla G, Fino C, et al. Intermittent antegrade warm blood cardioplegia in aortic valve replacement. J Card Surg. 1996;11:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1996.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fromes Y, Daghildjian K, Caumartin L, Fischer M, Rouquette I, Deleuze P, et al. A comparison of low vs conventional-dose heparin for minimal cardiopulmonary bypass in coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:488–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lichtenstein SV, Naylor CD, Feindel CM, Sykora K, Abel JG, Slutsky AS, et al. Intermittent warm blood cardioplegia. Warm heart investigators. Circulation. 1995;92(Suppl II):341–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Landymore RW, Marble AE, Fris J. Effect of intermittent delivery of warm blood cardioplegia on myocardial recovery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:1267–72. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)91372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bical OM, Fromes Y, Paumier D, Gaillard D, Foiret JC, Trivin F. Does warm antegrade intermittent blood cardioplegia really protect the heart during coronary surgery? Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;9:188–93. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(00)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Isomura T, Hisatomi K, Sato T, Hayashida N, Ohishi K. Interrupted warm blood cardioplegia for coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1995;9:133–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(05)80059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hayashida N, Isomura T, Sato T, Maruyama H, Higashi T, Arinaga K, et al. Minimally diluted tepid blood cardioplegia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:615–21. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guyton RA, Gott JP, Brown WM, Craver JM. Cold and warm myocardial protection techniques. Adv Card Surg. 1996;7:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hvass U, Depoix JP. Clinical study of normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in 100 patients with coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:46–51. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)00611-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Randomised trial of normothermic versus hypothermic coronary bypass surgery. The Warm Heart Investigators. Lancet. 1994;343:559–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guyton RA, Mellitt RJ, Weintraub WS. A critical assessment of neurological risk during warm heart surgery. J Card Surg. 1995;10(4 Suppl):488–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1995.tb00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hayashida N, Weisel RD, Shirai T, Ikonomidis JS, Ivanov J, Carson SM, et al. Tepid antegrade and retrograde cardioplegia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:723–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)01056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Engelman RM, Pleet AB, Rousou JA, Flack JE, 3rd, Deaton DW, Gregory CA, et al. What is the best perfusion temperature for coronary revascularization? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:1622–32. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zeng J, He W, Qu Z, Tang Y, Zhou Q, Zhang B. Cold blood versus crystalloid cardioplegia for myocardial protection in adult cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:674–81. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Behrendt D, Ganz P. Endothelial function. From vascular biology to clinical applications. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:40L–8L. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02963-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Moghimian M, Faghihi M, Karimian SM, Imani A, Houshmand F, Azizi Y. Role of central oxytocin in stress-induced cardioprotection in ischemic-reperfused heart model. J Cardiol. 2013;61:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Osaka S, Sezai A, Wakui S, Shimura K, Taniguchi Y, Hata M, et al. Experimental investigation of “hANP shot” using human atrial natriuretic peptide for myocardial protection in cardiac surgery. J Cardiol. 2012;60:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sohma R, Inoue T, Abe S, Taguchi I, Kikuchi M, Toyoda S, et al. Cardioprotective effects of low-dose combination therapy with a statin and an angiotensin receptor blocker in a rat myocardial infarction model. J Cardiol. 2012;59:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Apostolakis EE, Koletsis EN, Baikoussis NG, Siminelakis SN, Papadopoulos GS. Strategies to prevent intraoperative lung injury during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]