Abstract

Objective:

Epidural anesthesia is a central neuraxial block technique with many applications. It is a versatile anesthetic technique, with applications in surgery, obstetrics and pain control. Its versatility means it can be used as an anesthetic, as an analgesic adjuvant to general anesthesia, and for postoperative analgesia. Off pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery triggers a systemic stress response as seen in coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA), combined with general anesthesia (GA) attenuates the stress response to CABG. There is Reduction in levels of Plasma epinephrine, Cortisol and catecholamine surge, tumor necrosis factor-Alpha(TNF ά), interleukin-6 and leucocyte count.

Design:

A prospective randomised non blind study.

Setting:

A clinical study in a multi specialty hospital.

Participants:

Eighty six patients.

Material and Methods/intervention:

The study was approved by hospital research ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were randomised to receive either GA plus epidural (study group) or GA only (control group). Inclusion Criteria (for participants) were -Age ≥ 70 years, Patient posted for OPCAB surgery, and patient with comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, renal dysfunction). Serum concentration of Interlukin: – 6, TNF ά, cortisol, Troponin – I, CK-MB, and HsCRP (highly sensitive C reactive protein), was compared for both the group and venous blood samples were collected and compared just after induction, at day 2, and day 5 postoperatively. Time to mobilization, extubation, total intensive care unit stay and hospital stay were noted and compared. Independent t test was used for statistical analysis.

Primary Outcomes:

Postoperative complications, total intensive care unit stay and hospital stay.

Secondary Outcome:

Stress response.

Result:

Study group showed decreased Interlukin – 6 at day 2, TNF ά at day 2 and 5, troponin I at day 5, and decreased total hospital stay (p < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Thoracic epidural anesthesia decreases stress and inflammatory response to surgery and decreases hospital stay. However a large multicentre study may be needed to confirm it.

Keywords: Coronary artery bypass grafting, inflammatory markers, off pump coronary artery bypass, thoracic epidural anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

As a result of increasing life expectancy, the number of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has increased in the elderly. Advanced age is associated with the physiologic process of aging and decreased functional reserve of organs. These patients are often frail and have comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), and renal dysfunction.[1,2,3] These characteristics translate to increased postoperative complications and resource utilization following CABG. Advanced age remains an independent predictor of mortality and morbidity in CABG.[3]

Older patients have delayed extubation prolonged Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and hospital length of stay (HLOS), blood transfusion, respiratory complications, low output syndrome, stroke, hospital mortality, renal insufficiency, perioperative myocardial infarction (PMI), and arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias.[1,3,4,5,6]

Despite on-going advances in endovascular revascularization, CABG is expected to remain an indispensable method of coronary revascularization.[7] Furthermore, patient selection for surgery is not always straightforward as the majority of these patients are operated for symptoms rather than for longevity.[8]

In an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality in elderly patients for CABG, reappraisal of off-pump CAB (OPCAB) has shown promise in reducing the above mentioned postoperative complications in the elderly, compared with conventional CABG (CCABG) on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).[1,3] Several studies have demonstrated that CABG in patients more than 70 years of age can be performed successfully with good late outcomes through morbidity and morbidity remains higher as compared to younger patients.[1,3,5,9,10] Many studies have recommended that these patients should not be turned down for coronary revascularization because of advanced age alone.[1,11,12] Various benefits of thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) in high risk cardiac surgical patient such as earlier tracheal extubation, decreased pulmonary, cardiovascular, or renal complications are described.[13] The surgical treatment of this group of patients nonetheless poses general anesthesia (GA) related and ethical challenges. Nonanalgesic benefits of GA and TEA have not been well studied particularly in the high risk population. We undertook a study to analyze the nonanalgesic benefits of combined GA with TEA in elderly high risk subgroup of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a single center, prospective, randomized, controlled trail. Eligible patients were elderly (age > 70) undergoing primary OPCAB surgery without the use of CPB and cardioplegic arrest. Patient with infection over the spine, coagulation disorders, emergency cases, unstable angina, left main stem disease, patients with dysrhythmias, undergoing combined procedures, patient on intra-aortic balloon counter pulsation (IABP), and patient on antiplatelet agent, low molecular weight heparin or heparin infusion were excluded from the study.

Preoperative demographics age, sex, and clinical profile with regards to: Ejection fraction (EF), comorbid conditions (DM, COPD, cerebrovascular disease, PVD, renal dysfunction), and hypertension were noted. Time to extubation, time to mobilization, ICU, and HLOS were recorded. Postoperative complications such as reintubation, postoperative IABP requirement, blood and blood product transfusion rates, PMI, occurrence of stroke, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, new onset renal dysfunction, gastrointestinal complications, and respiratory complications were noted.

New onset renal dysfunction was defined as rise of serum creatinine to more than 2 mg/dl in patients with normal preoperative serum creatinine values or rise of more than 2 mg/dl from preoperative values if abnormal. PMI was defined as those developing electrocardiogram (ECG) changes-new Q waves on postoperative ECG ≥0.03 s in duration in two or more adjacent leads lasting till discharge, rise in creatine phosphokinase-MB (CPK-MB) and troponin I, new regional wall motion abnormalities. Respiratory complications like ventilator associated pneumonia or atelectasis requiring noninvasive ventilation in the postoperative period were noted. Atrial fibrillation was documented if it lasted more than 24 h. Stroke was documented if diagnosed on computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Blood sampling: CPK-MB, troponin I, interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), highly sensitive C-reactive protein (HsCRP), serum cortisol were measured. Venous blood samples for these were collected at the following time interval: Postanesthesia induction, day 2 and day 5.

HsCRP was measured using latex enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay. Troponin T (Tn-T) was measured using the immunometric method. Creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) was measured using creatine phosphate/GPO/POD – immunoassay method. Cortisol was measured using competitive immunoassay method. IL-6 and TNF-α were measured using ELISA. Serum concentration of IL-6, TNF-α, cortisol, CK-MB, Tn-T, and HsCRP, were compared between both the groups.

Study settings

The study was conducted at our tertiary care hospital. After approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital, written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Interventions

It was a nonblinded study. Patients were randomized to receive either GA plus TEA (study group) or GA (control group) by computer generated numbers in sealed envelopes.

Anesthetic technique

In both groups, the patients were premedicated with lorazepam 2 mg and pantoprazole 40 mg per orally a night before and on the morning of surgery. Anesthesia was induced with thiopentone sodium 2–4 mg/kg combined with fentanyl sulfate (3–5 μ/kg) and midazolam 0.03–0.04 mg/kg intravenously (IV). Neuromuscular blockade was achieved with 0.08–0.12 mg/kg pancuronium or vecuronium bromide and following tracheal intubation, the lungs were ventilated with oxygen and air to normocapnia. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane and intermittent doses of muscle relaxant, fentanyl sulfate, and midazolam. In addition, patients in the study group had a thoracic epidural catheter sited immediately before induction between C7-T1 and T1-T2 intervertebral space. The epidural needle was inserted using the hanging drop technique in the sitting position, and the epidural catheter was inserted 4–5 cm beyond the needle tip. The neuraxial block was established from T1 to T10 with an initial bolus of 6–14 ml ropivacaine 0.75%, followed by infusion of 5–15 ml/h ropivacaine 0.2%. The effect was confirmed by a sensory loss to cold pack and needle prick. If a “bloody tap” was to occur, the operation was postponed for 24 h and excluded from the study. Surgery commenced only if the neurologic examination was normal the next morning. Any focal neurologic abnormality was to be followed by urgent MRI scan to exclude epidural hematoma.

Surgical technique

Heparin (200 units/kg) was administered after harvesting the left internal mammary artery to achieve an activated clotting time of 300–350 s. On completion of all anastomoses, protamine sulfate was administered to reverse the effect of heparin and return the activated clotting time to <150 s.

Postoperative care

In the study group, the epidural infusion was continued for 72 h after surgery. Visual Analog Score for the intensity of pain was assessed on a scale of 1–10 with the maximum intensity of pain being graded as 10. The rate of infusion was titrated by the attending intensivist according to clinical need/pain score. “Top-up” bolus doses up to a maximum of 4 ml ropivacaine, 0.2%, were administered when the patient complained of pain. If more than three increases to the infusion rate or more than three epidural top-up doses were required in any hour, analgesia was considered inadequate, and a rescue analgesic tramadol hydrochloride 100 mg IV was administered. All patients in the control group received tramadol hydrochloride 100 mg IV 8 hourly. All other aspects of postoperative patient management were according to unit protocol.

Statistical methods

All the values are expressed as in terms of means and standard deviation. Qualitative/categorical data are expressed in terms of absolute number and percentages. Comparison between study and control groups was performed using independent Student's t-test. The Chi-square test was used for categorical data. Diagrams and charts are given wherever necessary to substantiate the important findings. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS version 18.0 (IBM, SPSS statistics).

RESULTS

Patient recruitment

Patient recruitment took place between December 2011 and November 2014. Eighty-six patients enrolled in the study were randomly assigned to study and control groups, with 40 assigned to study (five patients excluded from the study group due to protocol violations) and 46 to control group.

Protocol violations

There were five protocol violations in patients allocated to the study group, two epidural catheters were accidentally dislodged during shifting of the patient, one patient developed severe hypotension requiring a bolus of epinephrine during catheter placement without any clinical consequences. One OPCAB was converted to CABG due to hemodynamic instability during surgery. One patient withdrew consent from the trial. None of the patients had “bloody tap” during epidural catheter placement.

Baseline characteristics and operative details

Patient demographics are presented in Table 1. Patients mean age was 74.9 years in the control group (standard deviation [ SD] ± 4.162 years), and 74.2 years in the study group (SD ± 5.138). About 89.1% were males in control group and 88.6% in study group. Patient characteristics such as EF, the prevalence of COPD, DM, PVD, and hypertension were similar in both groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of patient demographics and various postoperative parameters

| Study parameters | Control group (n=46) | Study group (n=35) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic profile | |||

| Male, n (%) | 41 (89.1) | 31 (88.6) | 0.937 |

| Age (mean±SD) | 74.9±4.2 | 74.2±5.1 | 0.492 |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 25.2±4.4 | 26.1±4.2 | 0.386 |

| EF (mean±SD) | 48.2±9.7 | 48.3±7.8 | 0.989 |

| DM, n (%) | 23 (50.0) | 20 (57.1) | 0.523 |

| COPD, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 7 (20.0) | 0.252 |

| Renal dysfunction, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 1 (2.9) | 0.173 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 25 (56.8) | 17 (48.6) | 0.466 |

| PVD, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Postoperative parameters | |||

| Time to extubation (mean±SD) | 15.5±3.9 | 14.2±8.2 | 0.353 |

| Time to mobilization (mean±SD) | 49.4±11.5 | 14.2±8.2 | 0.977 |

| ICU stay (mean±SD) | 69.5±20.5 | 63.9±21.8 | 0.240 |

| Hospital stay (mean±SD) | 155.0±11.7 | 144.6±31.0 | 0.042* |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 23 (50.0) | 12 (34.3) | 0.157 |

| Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (8.6) | 0.188 |

| New onset renal dysfunction, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.212 |

| Gastrointestinal complications, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.380 |

| Respiratory complications, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.249 |

*P<0.05, statistically significant. Demographic profiles of the control group and study group were comparable. In postoperative parameters, only hospital stay is statistically significant. EF: Ejection fraction, ICU: Intensive Care Unit, BMI: Body mass index, DM: Diabetes mellitus, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PVD: Peripheral vascular disease, SD: Standard deviation

Primary outcome

The median time from surgery to discharge from the hospital was shorter by 10.33 h. In the study group, as compared to the control group (155 h in control and 144.6 in study group P = 0.042) [Table 1]. Time to extubation, time to mobilization, and ICU stay were comparable for both the groups (P > 0.05) [Table 1].

Secondary outcomes

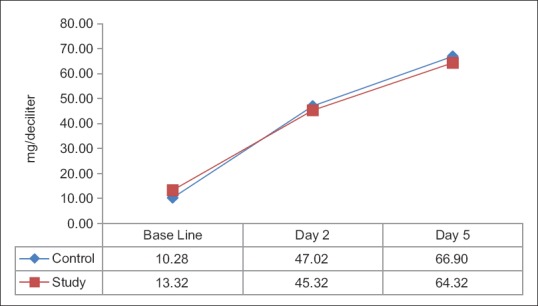

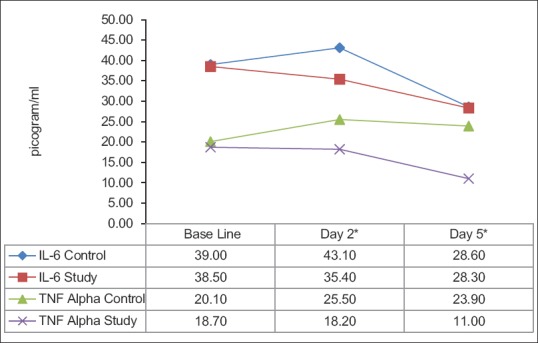

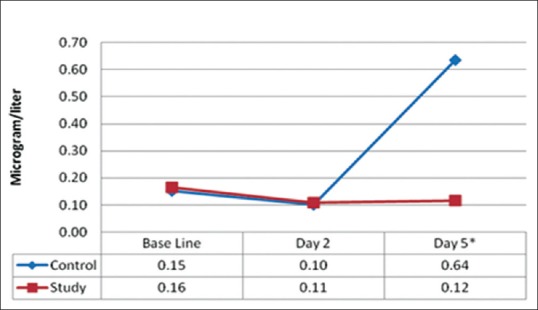

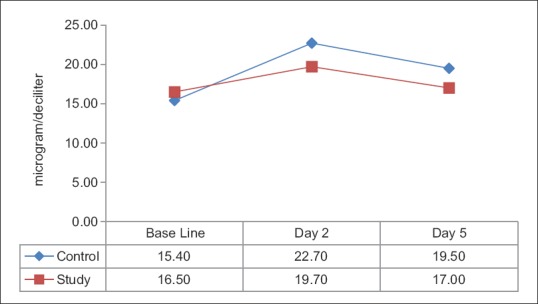

The baseline values of biochemical parameters such as IL-6, TNF-α, troponin I, HsCRP, CPK-MB were comparable between groups at postinduction (P > 0.05) [Figures 1–4]. IL-6 was significantly lower in the study group at day 2 (43.15 pg/ml in control group vs. 35.4 pg/ml in study group) (P < 0.044) [Figure 4]. TNF-α was significantly lower in the study group at day 2 and 5 (25.51 pg/ml in control group vs. 18.28 pg/ml in the study group at day 2 and 23.99 pg/ml in control group vs. 11.04 pg/ml in the study group at day 5) (P < 0.044 and 0.031), respectively [Figure 4]. Furthermore, troponin I was significantly lower in study group at day 5 (P < 0.049) (0.64 μg/L in control group vs. 0.12 μg/L in the study group at day 5) [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Values of highly sensitive C-reactive protein at different time points

Figure 4.

Values of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α at different time points. The values of interleukin-6 are significant at day 1. Values of and tumor necrosis factor-α is significant at day 1 and 2. *P < 0.05, statistically significant

Figure 3.

Values of troponin I at different time points. *P < 0.05, statistically significant

Figure 2.

Values of cortisol at different time points

The patients in the study and control groups had no significant difference in postoperative complication such as atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, new onset renal dysfunction, gastrointestinal, and respiratory complications [Table 1]. None of the patients in either group had a postoperative complication such as reintubation, postoperative IABP requirement, PMI, occurrence of stroke.

DISCUSSION

Old age remains an independent predictor of mortality and morbidity in CABG surgery.[3] Our study has clearly demonstrated that administration of perioperative TEA along with GA reduces the mean length of postoperative hospital stay by 10.33 h. In high risk elderly patient undergoing OPCAB surgery. A study on 300 patients found an average reduction of 1-day of hospital stay by adding TEA to GA with “conventional” postoperative analgesia in adult patients undergoing OPCAB surgery.[14]

The perioperative use of epidural analgesia has profound inhibitory effects on the body's response to surgery, improving a variety of postoperative morbidity parameters, and improves surgical outcome.[15] A meta-analysis on “role of epidural analgesia in surgical practice”[16] observed improvement in the surgical outcome through beneficial effects on perioperative pulmonary function, blunting surgical stress response and improved analgesia. A meta-analysis of 15 trials enrolling 1178 patients who were randomized to either GA or GA combined with TEA in patients undergoing CABG on CPB demonstrate that TEA + GA patients had a reduced incidence of dysrhythmias, pain, pulmonary complications, and ventilation times without any effect on the incidence of PMI or mortality.[17] Another study showed better analgesia, associated with physiotherapy cooperation, earlier extubation, and less psychological disorders.[18] We have also found TEA to be beneficial technique in patients with COPD and obesity (body mass index of more than 30 kg/m2) undergoing OPCAB surgery with better analgesia and pulmonary function test postoperatively.[19] A study on 60 patients undergoing CABG on the pump with TEA versus TEA + GA observed comparable ventilator time, ICU stay, pain, and cardiopulmonary complications in both groups of patients.[20] OPCAB also triggers a systemic stress response as seen in CCABG.[21] TEA combined with GA attenuates the stress response to CPB and CABG. This has been seen in a reduction in levels of plasma epinephrine,[22] cortisol and catecholamine surge,[23] TNF-α, leukocyte count, and procalcitonin.[24] In our study, we found significantly decreased TNF-α on day 2 and 5 and IL-6 on day 2 in the study group. Cystic fibrosis control group. To our knowledge, this is the first report of nonanalgesic benefits of TEA in high risk patients in the age group 70 years and above undergoing OPCAB surgery.

Epidural analgesia has also been seen to reduce the hypercoagualable response to surgery,[25] improve myocardial blood flow,[26] and reduce postoperative MI.[27] The main argument against the use of TEA for CCABG surgery is the fear of an increased risk of epidural hematoma caused by the need to administer a large dose of heparin immediately before CPB. This perceived increased risk cannot be quantified, but the incidence of epidural hematoma after catheter insertion without heparinization is approximately 1 in 10,000.[28] Such a risk must be balanced by important clinical advantages if the technique is to be justified. In OPCAB surgery, the need for heparinization is reduced to half the dose as that used for CCABG, making the use of epidural anesthesia a more attractive approach. There was one conversion to CPB in the study group, without any adverse effect. We had no such complication in this study.

We perform TEA regularly at our center with cumulative experience of more than 1000 without any case of epidural hematoma, but we strictly follow American Society of Regional Anesthesia and European Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines for safety.[29,30]

We did not find any difference in postoperative complications such as reintubation, postoperative IABP requirement, blood and blood product transfusion rates, perioperative MI, occurrence of stroke, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, new onset renal dysfunction, gastrointestinal, and respiratory complications. It may be because these complications have a low incidence in OPCAB, and the numbers were not significant.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study was that it was not blinded. The study was slow in recruiting because large numbers of patients were on intravenous heparin or antiplatelet agents. This may represent a significant limitation to the application of epidural anesthesia. The study was applicable only for patients who were aged above 70 years and undergoing OPCAB surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated that the addition of TEA to conventional GA accounts for a significant reduction in the stress and inflammatory response to surgery and decreases total hospital stay in high risk elderly patients undergoing OPCAB surgery. However, a large multi-centric study may be needed to confirm it.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yim AP, Arifi AA, Wan S. Coronary artery bypass grafting in the elderly: The challenge and the opportunity. Chest. 2000;117:1220–1. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascione R, Rees K, Santo K, Chamberlain MH, Marchetto G, Taylor F, et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting in patients over 70 years old: The influence of age and surgical technique on early and mid-term clinical outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:124–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd WD, Desai ND, Del Rizzo DF, Novick RJ, McKenzie FN, Menkis AH. Off-pump surgery decreases postoperative complications and resource utilization in the elderly. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1490–3. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00951-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demaria RG, Carrier M, Fortier S, Martineau R, Fortier A, Cartier R, et al. Reduced mortality and strokes with off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting surgery in octogenarians. Circulation. 2002;106(12 Suppl 1):I5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura N, Urita R, Watanabe T, Kitano I, Murakami T. Surgical results of coronary artery bypass grafting in patients older than 75 years. Kyobu Geka. 1997;50:656–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christenson JT, Schmuziger M, Maurice J, Simonet F, Velebit V. How safe is coronary bypass surgery in the elderly patient?. Analysis of 111 patients aged 75 years or more and 2939 patients younger than 75 years undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting in a private hospital. Coron Artery Dis. 1994;5:169–74. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamoun NF, Xu M, Leventhal M, Bashour M. A Propensity Matched Comparison of Patients 85 Years and Older with Those 55 to 65 Years on Outcome Following CABG Surgery (Abstract) Anesthesiology. 2005;103:A1465. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weintraub WS. Coronary operations in octogenarians: Can we select the patients? Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:875–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00590-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura Y, Nakano K, Nakatani H, Gomi A, Sato A, Sugimoto K. Hospital and mid-term outcomes in elderly patients under-going off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting – Comparison with younger patients. Circ J. 2004;68:1184–8. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deuse T, Detter C, Samuel V, Boehm DH, Reichenspurner H, Reichart B. Early and midterm results after coronary artery bypass grafting with and without cardiopulmonary bypass: Which patient population benefits the most? Heart Surg Forum. 2003;6:77–83. doi: 10.1532/hsf.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapira I, Isakov A, Heller I, Topilsky M. Elderly patients as candidates for bypass? Chest. 2001;119:318–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirose H, Amano A, Yoshida S, Takahashi A, Nagano N, Kohmoto T. Coronary artery bypass grafting in the elderly. Chest. 2000;117:1262–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta Y, Arora D, Vats M. Epidural analgesia in high risk cardiac surgical patients. HSR Proc Intensive Care Cardiovasc Anesth. 2012;4:11–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caputo M, Alwair H, Rogers CA, Pike K, Cohen A, Monk C, et al. Thoracic epidural anesthesia improves early outcomes in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:380–90. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318201f571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekatodramis G. Regional anesthesia and analgesia: Their role in postoperative outcome. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moraca RJ, Sheldon DG, Thirlby RC. The role of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in surgical practice. Ann Surg. 2003;238:663–73. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094300.36689.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu SS, Block BM, Wu CL. Effects of perioperative central neuraxial analgesia on outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery: A meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:153–61. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royse C, Royse A, Soeding P, Blake D, Pang J. Prospective randomized trial of high thoracic epidural analgesia for coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma M, Mehta Y, Sawhney R, Vats M, Trehan N. Thoracic epidural analgesia in obese patients with body mass index of more than 30 kg/m2 for off pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2010;13:28–33. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.58831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fillinger MP, Yeager MP, Dodds TM, Fillinger MF, Whalen PK, Glass DD. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia: Effects on recovery from cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:15–20. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2002.29639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velissaris T, Tang AT, Murray M, Mehta RL, Wood PJ, Hett DA, et al. A prospective randomized study to evaluate stress response during beating-heart and conventional coronary revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:506–12. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loick HM, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Junker R, Erren M, Berendes E, et al. High thoracic epidural anesthesia, but not clonidine, attenuates the perioperative stress response via sympatholysis and reduces the release of troponin T in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:701–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganapathy S, Murkin JM, Dobkowski W, Boyd D. Stress and inflammatory response after beating heart surgery versus conventional bypass surgery: The role of thoracic epidural anesthesia. Heart Surg Forum. 2001;4:323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bach F, Grundmann U, Bauer M, Buchinger H, Soltész S, Graeter T, et al. Modulation of the inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass by dopexamine and epidural anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:1227–35. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.461010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuman KJ, McCarthy RJ, March RJ, DeLaria GA, Patel RV, Ivankovich AD. Effects of epidural anesthesia and analgesia on coagulation and outcome after major vascular surgery. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:696–704. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nygård E, Kofoed KF, Freiberg J, Holm S, Aldershvile J, Eliasen K, et al. Effects of high thoracic epidural analgesia on myocardial blood flow in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2005;111:2165–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163551.33812.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beattie WS, Badner NH, Choi P. Epidural analgesia reduces postoperative myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:853–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakravarthy M, Nadiminti S, Krishnamurthy J, Thimmannagowda P, Jawali V, Royse CF, et al. Temporary neurologic deficits in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with thoracic epidural supplementation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18:512–20. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, Kopp SL, Benzon HT, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Third Edition) Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:64–101. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181c15c70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gogarten W, Vandermeulen E, Van Aken H, Kozek S, Llau JV, Samama CM, et al. Regional anaesthesia and antithrombotic agents: Recommendations of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:999–1015. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833f6f6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]