Abstract

Abstract—Activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) leads to cell growth and survival. We tested the hypothesis that inhibition of mTOR would increase infarct size and decrease microregional O2 supply/consumption balance after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion. This was tested in isoflurane-anesthetized rats with middle cerebral artery blockade for 1 h and reperfusion for 2 h with and without rapamycin (20 mg/kg once daily for two days prior to ischemia). Regional cerebral blood flow was determined using a C14-iodoantipyrine autoradiographic technique. Regional small-vessel arterial and venous oxygen saturations were determined microspectrophotometrically. The control ischemic-reperfused cortex had a similar blood flow and O2 consumption to the contralateral cortex. However, microregional O2 supply/consumption balance was significantly reduced in the ischemic-reperfused cortex. Rapamycin significantly increased cerebral O2 consumption and further reduced O2 supply/consumption balance in the reperfused area. This was associated with an increased cortical infarct size (13.5 ± 0.8% control vs. 21.5 ± 0.9% rapamycin). We also found that ischemia–reperfusion increased AKT and S6K1 phosphorylation, while rapamycin decreased this phosphorylation in both the control and ischemic-reperfused cortex. This suggests that mTOR is important for not only cell survival, but also for the control of oxygen balance after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion.

Keywords: mammalian target of rapamycin, rapamycin, cerebral ischemia–reperfusion, oxygen supply/consumption, cerebral blood flow

INTRODUCTION

In focal cerebral ischemia, early restoration of regional cerebral blood flow is the primary means of treatment. It is usually beneficial and reduces ischemic brain injury (Alexandrov, 2010; Gomis and Davalos, 2014). However, restoration of blood flow may not always improve neurologic outcome because restoration of blood flow to an ischemic area may lead to some pathophysiologic changes in that region (Shi and Liu, 2007). In addition, cerebral blood flow, glucose utilization and O2 consumption may or may not be fully restored after reperfusion (Martin et al., 2009; Tichauer et al., 2009; Weiss et al., 2013). Microregional O2 supply/consumption balance is heterogeneous and reperfusion shifts this balance lower and increases its heterogeneity (Weiss et al., 2013). New agents that increase cell survival and improve oxygen supply/consumption balance could act to further reduce the degree of stroke damage (Kaur et al., 2013).

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a protein kinase that promotes cell growth and survival that might prove to be a viable target for treatment of the damaged or ischemic brain (Hwang and Kim, 2011; Don et al., 2012). It is part of two protein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, and more recently has been shown to play a central role in the control of cellular metabolism (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). The best known rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 target is S6K1, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ribosomal subunit S6 to control translation initiation. Activation of mTORC1 increases protein synthesis and metabolism (Morita et al., 2015) whereas inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin downregulates S6K activation, S6 phosphorylation and protein synthesis. Prolonged rapamycin treatment can indirectly inhibit mTORC2 and Akt activation by preventing the association of mTOR with mTORC2 components rictor and SIN1 (Sarbassov et al., 2006). There is also evidence that mTOR can activate hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (Chen et al., 2012b). This could enhance glycolytic flux and alter vascular growth or the degree of vasodilation. Some of these changes could protect the injured brain (Don et al., 2012).

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin would worsen the damage after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion and also adversely affect microregional O2 supply/consumption balance in the reperfused region. This was tested in isoflurane-anesthetized rats subjected to middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion and reperfusion with and without rapamycin treatment. We found that mTOR inhibition with rapamycin increased the damage after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion, increased cerebral metabolism and reduced microregional oxygen balance in the injured rat brain. This suggests that activation of mTOR might reverse these effects in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

This investigation was conducted in accordance to US Public Health Service Guidelines using the Guide for the Care of Laboratory Animals (DHHS Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and was approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Sixteen male Fischer 344 rats (3 months) were randomly divided into a cerebral ischemic-reperfused (n = 8) and rapamycin-treated ischemic-reperfused (n = 8) group. In the rapamycin-treated animals, 20 mg/kg of rapamycin (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA) dissolved in normal saline and 10% DMSO was injected ip once a day for two days. Experiments were conducted 48 h after the first injection. In the control group, vehicle was injected. Each rat was used to measure regional cerebral blood flow and microscopic arterial and venous oxygen saturations (SvO2). The rats were initially anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in an air and oxygen mixture through a tracheal tube to maintain the arterial pO2 at about 100 mmHg. A femoral artery and vein were cannulated. The venous catheter was used to administer radioactive tracer. The artery catheter was connected to a pressure transducer and an Iworx data acquisition system to monitor heart rate and blood pressure. This catheter was also used to obtain arterial blood samples for analysis of hemoglobin, blood gases and pH using a Radiometer blood gas analyzer. The isoflurane concentration was decreased to 1.4%. Body temperature was monitored and maintained at 37 °C with a servo-controlled rectal thermistor probe and a heating lamp.

We used the transient occlusion of the MCA using an intraluminal thread as our technique to study cerebral ischemia–reperfusion (Longa et al., 1989; Lipsanen and Jolkkonen, 2011; Weiss et al., 2013). The common carotid artery was exposed through a midline ventral cervical incision and carefully separated from the adjacent nerve. Then a 4.0 monofilament thread with its tip rounded was inserted into the stump of the external carotid artery and advanced approximately 1.7 cm into the internal carotid artery until resistance was felt. The filament was held in place for 60 min blocking the MCA and then it was removed, allowing reperfusion, and the external carotid artery was closed. Measurements were performed after 120 min of reperfusion. Regional cerebral blood flow and microscopic O2 saturations of small veins and arteries were determined in several brain regions in both groups of animals.

Regional cerebral blood flow was measured by the 14C-iodoantipyrine quantitative autoradiographic technique. Briefly, 40 lCi of 14C-iodoantipyrine was infused intravenously. When the isotope entered the venous circulation, the arterial catheter was cut to 20 mm to minimize smearing. Twenty μl blood samples were obtained from the arterial catheter approximately every 3 s during next 60 s. At the moment when the last sample was obtained the animal was decapitated and the head was frozen in liquid nitrogen. While frozen, the brain was sampled from three regions: ischemic cortex, contralateral cortex and pons. The brain samples were sectioned (20 μm) on a microtome-cryostat and the sections were exposed to X-ray film to obtain an autoradiogram. The cerebral 14C-iodoantipyrine concentrations were determined by reference to precalibrated standards using the NIH imageJ program. For each brain region examined, a minimum of eight optical density measurements were made, each on different sections. Blood samples were placed in a tissue solubilizer and 24 h later put in a counting liquid. These samples were counted on a liquid scintillation counter and were quench corrected. Regional cerebral blood flows were then calculated.

Alternate sections from regions of the same brain (ischemic cortex, contralateral cortex and pons) were used for the determination of arterial and venous O2 saturation. The cortical regions were from a ~5 mm plug from the parietal cortex over the MCA. Details of this technique have been published previously (Buchweitz-Milton and Weiss, 1987; Zhu and Weiss, 1991). Briefly, the brain sections were cut into wafers at −20 °C. Twenty-micron-thick sections were obtained at −35 °C under a N2 atmosphere. The sections were transferred to precooled glass slides and covered with degassed silicone oil and a coverslip. These slides were placed on a microspectrophotometer fitted with an N2-flushed cold stage to obtain readings of optical density at 568, 523 and 560 nm. This three-wavelength method corrects for the light scattering in the frozen blood. Only vessels cut in transverse section were studied so that the path of light traversed only the blood. The size of the measuring spot was 8 lm in diameter. Readings were obtained to determine O2 saturation in five arteries and 10 veins (20–60 μm in diameter) in each region. The O2 content of blood was determined by multiplying the percent O2 saturation by the hemoglobin concentration times 1.36, the maximal binding capacity of hemoglobin for O2 per gram. The difference between the average arterial and venous O2 contents (regional O2 extraction) was then obtained. Using the Fick principle, we calculated the O2 consumption for each region as the product of average flow and O2 extraction. This method has been validated in the brain (Buchweitz-Milton and Weiss, 1987).

An additional four rats in each group were used to determine the size of the infarct. The brain was removed and was sliced in coronal sections. There were typically 3–4 slices of approximately 2–3 mm thickness of brain tissue each. For tetrazolium staining, a 0.05% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma) solution in PBS was prepared and warmed to 37 °C. The brain slices were placed in the solution and were incubated for 30 min. The tetrazolium chloride solution was then poured off and the slices were washed three times in PBS, 1 min per wash. To keep the slices from drying out, each slice was placed in a small weighing boat with PBS. The slides were then scanned and the scanned images were measured for total and infarcted areas in the cortex using NIH ImageJ. Cortical infarcted areas were reported as percent of total cortical area.

In three additional control and rapamycin-treated animals, brain tissue was lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3PO4, 1 mM NaF, and protease inhibitor cocktail). The lysates were centrifuged at 16000g for 30 min at 4 °C. Total extracts were resolved by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Antibodies to S6, p-S6 (Ser240/244) and Akt, p-Akt (Ser473) were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Western blot analysis was then performed.

Analysis of variance using a repeated measure design was performed for the various measurements to assess the difference between the different regions and treatments examined for hemodynamic, blood gases, cerebral blood flow, O2 extraction and O2 consumption values. Post hoc testing of multiple comparisons was performed using Tukey’s procedure. The coefficient of variation (CV) of SvO2 was used to compare changes in heterogeneity. The CV was calculated as 100 × SD/mean. A χ2 test was used to assess differences in the distribution of SvO2 and differences in the number of low O2 saturated veins between groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Hemodynamic and blood gas parameters in the ischemic-reperfused (1 h MCA occlusion + 2 h reperfusion) and rapamycin-treated ischemia–reperfusion groups of rats were within the normal ranges for anesthetized rats (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in arterial blood pressures between groups. Heart rates were also similar between the two groups of rats. Arterial blood gases and pH were controlled and also were not significantly different between the two experimental groups.

Table 1.

Hemodynamic and blood gas values for the ischemic-reperfusion and rapamycin ischemic-reperfusion groups

| Ischemic- reperfused |

Rapamycin ischemic- reperfused |

|

|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

127 ± 11 | 138 ± 9 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

91 ± 10 | 96 ± 8 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) |

103 ± 10 | 111 ± 8 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 284 ± 21 | 263 ± 18 |

| Arterial PO2 (mmHg) | 115 ± 11 | 121 ± 6 |

| Arterial PCO2 (mmHg) | 30 ± 3 | 33± 3 |

| pH | 7.35 ± 0.03 | 7.37 ± 0.02 |

Values are mean ± S.E.M. (N = 8 per group).

Cerebral blood flow in the ischemic-reperfused cortex was not significantly different compared to the contralateral cortex in the control group, Table 2. In the rapamycin group, flow in the ischemic-reperfused region was also similar to the value in the contralateral cortex. The differences in flow between the control and rapamycin groups were not statistically significant in either the ischemic-reperfused and contralateral cortical regions.

Table 2.

Regional cerebral blood flow (ml/min/100 g), cerebral O2 extraction (ml O2/100 ml) and O2 supply/consumption in control and rapamycin-treated rats

| Control | Rapamycin | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood flow | ||

| IC | 85.6 ± 6.8 | 102.1 ± 6.6 |

| CC | 96.7 ± 8.4 | 106.4 ± 9.5 |

| O2 extraction | ||

| IC | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 6.7 ± 0.4† |

| CC | 4.7 ± 0.3* | 4.9 ± 0.3* |

| O2 supply/consumption | ||

| IC | 2.48 ± 0.06 | 2.22 ± 0.02† |

| CC | 2.92 ± 0.05* | 3.00 ± 0.04* |

Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (N = 8 per group), IC = ischemic-reperfused cortex, CC = contralateral cortex.

Significantly different from IC.

Significantly different from Control group.

The oxygen extraction of the ischemic-reperfused cortex was significantly elevated (+17%) compared the contralateral cortex in the control group, Table 2. Similarly, the oxygen extraction was also significantly elevated in the rapamycin group in the ischemic-reperfused region (+37%) compared to the contralateral cortex. The O2 extraction in the ischemic-reperfused cortical region of the rapamycin group was significantly higher in comparison to the same region in the control group.

Arterial O2 saturations were similar in all regions and groups (data not shown). However venous O2 saturation was significantly lower in the ischemic-reperfused region compared to the contralateral cortex in both groups. The distribution of small-vein (20–60 lm diameter) O2 saturations was heterogeneous in all cortical regions, Fig. 1. There was a shift to lower values in the ischemic-reperfused cortex compared to the contralateral cortex of both experimental groups. The number of vessels with O2 saturations below 55% was significantly greater in the ischemic-reperfused cortex compared to the contralateral cortex of both groups. However, the number of low saturation veins was significantly greater in the rapamycin group (74 of 80) compared to the control group of rats (34 of 80). The coefficient of variation (CV = 100 * SD/mean, a measure of heterogeneity) increased (12.5 vs. 5.5) in the ischemic-reperfused cortex compared to contralateral cortex in the control group. However, the CV did not increase in the ischemic-reperfused region of the rapamycin group (5.1 vs. 4.9). The ischemic-reperfused cortex of the rapamycin had less very low saturation veins and a narrower but lower distribution of O2 saturations compared to the control group.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of O2 saturations (%) of small veins in the ischemic-reperfused and the contralateral cortex of the control (top) and the rapamycin-treated group (bottom). Note the shift to lower values in the ischemic-reperfused cortex compared to the contralateral cortex in both groups.

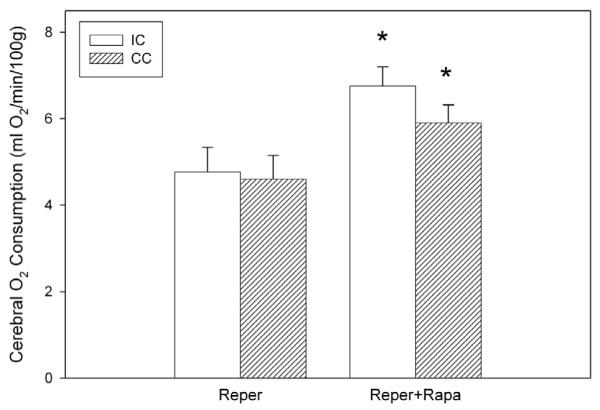

Cerebral O2 consumption in the ischemic-reperfused cortex was similar to the contralateral cortex in both the control and rapamycin-treated groups, Fig. 2. However, cerebral oxygen consumption was significantly higher in the rapamycin-treated group compared to that observed in the control group. This was found in both the rapamycin-treated ischemic-reperfused cortex (+23%) as well as the contralateral cortex (+28%).

Fig. 2.

Cerebral O2 consumption in the ischemic-reperfused cortex (IC) and contralateral cortex (CC) of the control (Reper, n = 8) and rapamycin (Rapa, n = 8) groups subjected to 1 h of MCA occlusion and 2 h of reperfusion. *significantly different from comparable control region.

The ratio of O2 supply to O2 consumption was lower in the ischemic-reperfused cortex compared to the contralateral cortex in both the control and rapamycin-treated groups, Table 2. This ratio was significantly lower in the ischemic-reperfused cortex of the rapamycin group compared to the same region in the control group. The size of cortical infarct measured as the percentage of total cortical area determined at the end of the two hour reperfusion period was significantly greater in the rapamycin-treated group compared to the control group (control 13.5 ± 0.8% vs. rapamycin 21.5 ± 0.9%).

We also examined the effects of ischemia–reperfusion with and without rapamycin on the phosphorylation of the mTOR targets, Akt and S6K1, Fig. 3. Neither total Akt nor S6K1 levels were affected by ischemia–reperfusion or rapamycin treatment. The level of phosphorylation in the cortex of both Akt and S6 increased with ischemia– reperfusion. Prolonged rapamycin treatment decreased these levels of phosphorylation of Akt and S6 in both the ischemic-reperfused and contralateral cortex below control levels.

Fig. 3.

Protein levels and signaling for Akt and S6 in ischemia–reperfusion (control) and ischemia–reperfusion plus rapamycin (Rapa) in the contralateral (N) and ischemic-reperfused (I) cortex (top). Note the increase in signaling in the ischemic reperfused cortex and the decrease after rapamycin treatment. The fold increase or decrease in phosphorylation normalized to the control-non-ischemic region is shown. The quantitation of these changes is also shown (bottom).

We also compared the effects of rapamycin on brain O2 supply/consumption balance in a remote cerebral region, the pons. Blood flow (control: 119 ± 10 vs. rapamycin 152 ± 13 ml/min/100 g) in the pons was significantly higher in the rapamycin group. The oxygen extraction (control: 4.6 ± 0.2 vs. rapamycin 4.9 ± 0.3 ml O2/100 ml) was similar between the two groups in the pons. However, the oxygen consumption of the pons was significantly higher in the rapamycin group (control 5.4 ± 0.5 vs. rapamycin 7.5 ± 0.8 ml O2/min/100 g). The ratio of O2 supply to O2 consumption was not significantly altered in the rapamycin-treated group (control 2.96 ± 0.05 vs. rapamycin 3.07 ± 0.03).

DISCUSSION

Despite reperfusion of the MCA, there was a significant area of cell death even though local oxygen consumption and blood flow were largely restored. The ratio of O2 supply to consumption was significantly reduced and the number of low-saturation small veins was increased in this area. This was similar to our previous report (Weiss et al., 2013). The major new finding of this study was that rapamycin increased both infarct size and cerebral oxygen consumption. In addition, the number of low O2 saturation small veins was significantly increased despite a reduction in the variance (reduced numbers of both very low and high saturation veins). This might imply that activation of mTOR may play a protective role after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion.

With blockage of a cerebral artery, blood flow and O2 consumption decline (Buchweitz-Milton and Weiss, 1987; Dirnagl, 2012). Glucose utilization was also depressed in cerebral ischemia (Martin et al., 2009). Cerebral oxygen extraction was also increased and venous O2 saturations declined in the affected region. This has been observed in both cats and rats (Buchweitz-Milton and Weiss, 1987; Chi et al., 2010). Tissue PO2 also significantly declined (Shi and Liu, 2007). Deoxyhemoglobin levels may be increased in humans with stroke (Sakatani et al., 2007). Without further treatment, large parts of this area will suffer both loss of function and irreversible damage (Lipsanen and Jolkkonen, 2011; Dirnagl, 2012). With reperfusion, blood flow was partially restored and O2 consumption returned to the value found in the contralateral cortex (Weiss et al., 2013). However, the local O2 supply/-consumption ratio remained significantly depressed. Small cerebral vein O2 saturations were lowered and their heterogeneity increased compared to the contralateral cortex, see Fig. 1. This indicated many small regions of low oxygenation within the reperfused cortical region in the control group. In addition, we found significant cell damage within the ischemic-reperfused cortex.

The administration of rapamycin prior to ischemia– reperfusion significantly increased the size of the damaged cortical area compared to the control group (+59%) in our study. It has been suggested that activation of mTOR should be neuroprotective after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion (Pastor et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2012a; Chong et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). However, other investigators have suggested that treatment with rapamycin, and therefore inhibition of mTOR, is neuroprotective (Guo et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2014). These differences may depend on the time or route of administration or the relative importance of the various multifaceted effects (discussed below) of mTOR activation.

We found that cerebral oxygen consumption was increased in all examined regions after rapamycin treatment, which leads to inhibition of mTOR, Fig. 2. This is somewhat surprising in that activation of mTOR usually leads to increased protein synthesis, cell growth and metabolism (Morita et al., 2015). In certain cases, a negative feedback loop for rapamycin treatment acting through PI3K activation could occur, which could lead to an increased level of cerebral metabolism and protein synthesis (Harrington et al., 2005). Rapamycin has also been reported to protect mitochondrial function (Li et al., 2014), which could be associated with increased cerebral metabolism.

The mTOR is part of two protein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, and is involved in the control of cell growth and metabolism (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Among the two complexes, mTORC1 is better understood largely due to the inhibitory effects of rapamycin on this complex. The most well-characterized rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 target is S6K1, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ribosomal subunit S6 to control translation initiation. We saw a decreased activation of S6K1 with rapamycin, Fig. 3. There is good evidence that activation of mTOR increases protein synthesis and metabolism (Morita et al., 2015). Inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin downregulates S6K activation and S6 phosphorylation. These effects should reduce metabolism and protein synthesis. This may explain the reported beneficial effects of short-term rapamycin (Guo et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2014). Our chronic rapamycin treatment regime appeared to inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2.

The mTORC2 complex, which is not acutely rapamycin-sensitive, responds to growth factors and promotes the activation of Akt via phosphorylation (Oh and Jacinto, 2011). Prolonged rapamycin treatment can indirectly inhibit mTORC2 and Akt activation by preventing association of mTOR with mTORC2 components rictor and SIN1 (Sarbassov et al., 2006). We observed a decreased Akt signaling after rapamycin. Active Akt impinges on mTORC1 signaling via negative regulation of TSC1/2 and consequently relieves suppression of mTORC1 by TSC1/2 (Huang and Manning, 2008). This could also affect brain metabolism. Further work is necessary to determine which of these pathways are responsible for the rapamycin-induced increases in cerebral metabolism. Activation of some of these mTOR pathways has been reported to be neuroprotective after cerebral ischemia (Papadakis et al., 2013). We observed an increased level of signaling of both Akt and S6K1 after ischemia–reperfusion. The effects of mTOR signaling during ischemia are controversial, but activation has been suggested to be protective (Hwang and Kim, 2011; Chen et al., 2012a; Chong et al., 2013).

Our biochemical analysis revealed that both mTORC1 and mTORC2 were inhibited under our conditions. Recent studies indicate that activation of Akt via phosphorylation at the mTORC2-targeted site is required for cell adaptation and survival during metabolic stress (Shin et al., 2015). Thus, defining the optimal dosage, time and/or route of administration would be crucial to prevent mTORC2/Akt inactivation and thus obtain beneficial effects of mTOR inhibition during ischemia.

We found that the ischemic-reperfused brain had significantly reduced small-vein O2 saturations and increased O2 extraction. Tissue PO2 was reported to be significantly reduced by cerebral ischemia, but only partially restored by reperfusion (Shi and Liu, 2007). Both venous O2 saturation and tissue PO2 are very heterogeneously distributed in the ischemic-reperfused brain (Shi and Liu, 2007; Weiss et al., 2013). Treatment with rapamycin led to increased oxygen consumption in the ischemic-reperfused region, with no significant change in cerebral blood flow. Blood flow maintenance may be regulated by rapamycin’s effect in increasing nitric oxide production (Lin et al., 2013). This increase in metabolism after rapamycin treatment was associated with reduced average small-vein O2 saturation and elevated regional O2 extraction in the ischemic-reperfused region below that of the contralateral cortex as well as control group values.

Rapamycin significantly reduced average venous O2 saturation in the ischemic-reperfused cortex. However the heterogeneity of this distribution was also reduced as noted by the reduced CV of venous O2 saturations. This was associated with lack of very low or high small-vein O2 saturations, Fig. 1. The reduced low values may be linked to the increased cell death we and others have reported with chronic rapamycin (Chong et al., 2013). While the reduced high values of venous O2 saturations may be associated with areas of increased nitric oxide production (Lin et al., 2013). Other agents, such as anesthetics, can also affect the heterogeneity of small-vein O2 saturation in the ischemic-reperfused cortex (Chi et al., 2015).

In summary, there was significant cell death even though local oxygen consumption and blood flow were largely restored in the ischemic-reperfused region. The ratio of O2 supply to consumption was significantly reduced and the number of low saturation veins was increased in this area (Weiss et al., 2013). The major finding of this study was that rapamycin increased both infarct size and cerebral oxygen consumption. In addition, the number of low-O2 saturation veins was increased despite a reduction in the variance (reduced numbers of both very low and high saturation veins). This might imply that mTOR activation may play a protective role after cerebral ischemia–reperfusion.

Abbreviations

- CV

coefficient of variation

- MCA

middle cerebralartery

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- SvO2

venous oxygen saturations

REFERENCES

- Alexandrov AV. Current and future recanalization strategies for acute ischemic stroke. J Intern Med. 2010;267:209–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchweitz-Milton E, Weiss HR. effect of MCA occlusion on brain O2 supply and consumption determined microspectrophotometrically. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H454–H460. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.2.H454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Qu Y, Tang B, Xiong T, Mu D. Role of mammalian target of rapamycin in hypoxic or ischemic brain injury: potential neuroprotection and limitations. Rev Neurosci. 2012a;23:279–287. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2012-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Xiong T, Qu Y, Zhao F, Ferriero D, Mu D. MTOR activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and inhibits neuronal apoptosis in the developing rat brain during the early phase after hypoxia-ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2012b;507:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi OZ, Hunter C, Liu X, Weiss HR. The effects of isoflurane pretreatment on cerebral blood flow, capillary permeability, and oxygen consumption in focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1412–1418. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d6c0ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi OZ, Grayson J, Barsoum S, Liu X, Dinani A, Weiss HR. effects of dexmedetomidine on microregional O2 balance during reperfusion after focal cerebral ischemia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Yao Q, Li HH. The rationale of targeting mammalian target of rapamycin for ischemic stroke. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1598–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U. Pathobiology of injury after stroke: the neurovascular unit and beyond. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1268:21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Don AS, Tsang CK, Kazdoba TM, D’Arcangelo G, Young W, Zheng XF. Targeting mTOR as a novel therapeutic strategy for traumatic CNS injuries. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis M, Davalos A. Recanalization and reperfusion therapies of acute ischemic stroke: what have we learned, what are the major research questions, and where are we headed? Front Neurol. 2014;5:226. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Feng G, Miao Y, Liu G, Xu C. Rapamycin alleviates brain edema after focal cerebral ischemia reperfusion in rats. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2014;36:211–223. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2014.913616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington LS, Findlay GM, Lamb RF. Restraining PI3K: mTOR signalling goes back to the membrane. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008;412:179–190. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SK, Kim HH. The functions of mTOR in ischemic diseases. BMB Rep. 2011;44:506–511. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2011.44.8.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H, Prakash A, Medhi B. Drug therapy in stroke: from preclinical to clinical studies. Pharmacology. 2013;92:324–334. doi: 10.1159/000356320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. MTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhang T, Wang J, Zhang Z, Zhai Y, Yang GY, Sun X. Rapamycin attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction via activation of mitophagy in experimental ischemic stroke. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;444:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AL, Zheng W, Halloran JJ, Burbank RR, Hussong SA, Hart MJ, Javors M, Shih YY, Muir E, Solano Fonseca R, Strong R, Richardson AG, Lechleiter JD, Fox PT, Galvan V. Chronic rapamycin restores brain vascular integrity and function through NO synthase activation and improves memory in symptomatic mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1412–1421. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsanen A, Jolkkonen J. Experimental approaches to study functional recovery following cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3007–3017. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0733-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Rojas S, Pareto D, Santalucia T, Millan O, Abasolo I, Gomez V, Llop J, Gispert JD, Falcon C, Bargallo N, Planas AM. Depressed glucose consumption at reperfusion following brain ischemia does not correlate with mitochondrial dysfunction and development of infarction: an in vivo positron emission tomography study. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2009;6:82–88. doi: 10.2174/156720209788185650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M, Gravel SP, Hulea L, Larsson O, Pollak M, St-Pierre J, Topisirovic I. MTOR coordinates protein synthesis, mitochondrial activity and proliferation. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(4):473–480. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.991572. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/15384101.2014.991572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh WJ, Jacinto E. MTOR complex 2 signaling and functions. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2305–2316. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.14.16586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis M, Hadley G, Xilouri M, Hoyte LC, Nagel S, McMenamin MM, Tsaknakis G, Watt SM, Drakesmith CW, Chen R, Wood MJ, Zhao Z, Kessler B, Vekrellis K, Buchan AM. Tsc1 (hamartin) confers neuroprotection against ischemia by inducing autophagy. Nat Med. 2013;19:351–357. doi: 10.1038/nm.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor MD, Garcia-Yebenes I, Fradejas N, Perez-Ortiz JM, Mora-Lee S, Tranque P, Moro MA, Pende M, Calvo S. MTOR/S6 kinase pathway contributes to astrocyte survival during ischemia. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22067–22078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H, Su FY, Wan S, Chen Y, Cheng YQ, Liu AJ. The antiaging activity and cerebral protection of rapamycin at micro-doses. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20:991–998. doi: 10.1111/cns.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakatani K, Murata Y, Fujiwara N, Hoshino T, Nakamura S, Kano T, Katayama Y. Comparison of blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging and near-infrared spectroscopy recording during functional brain activation in patients with stroke and brain tumors. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:062110. doi: 10.1117/1.2823036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Liu KJ. Cerebral tissue oxygenation and oxidative brain injury during ischemia and reperfusion. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1318–1328. doi: 10.2741/2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Buel GR, Wolgamott L, Plas DR, Asara JM, Blenis J, Yoon SO. ERK2 mediates metabolic stress response to regulate cell fate. Mol Cell. 2015;59:382–398. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichauer KM, Elliott JT, Hadway JA, Lee TY, St Lawrence K. Cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen and amplitude-integrated electroencephalography during early reperfusion after hypoxia-ischemia in piglets. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1506–1512. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91156.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HR, Grayson J, Liu X, Barsoum S, Shah H, Chi OZ. Cerebral ischemia and reperfusion increases the heterogeneity of local oxygen supply/consumption balance. Stroke. 2013;44:2553–2558. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Sun F, Wang J, Mao X, Xie L, Yang SH, Su DM, Simpkins JW, Greenberg DA, Jin K. MTOR signaling inhibition modulates macrophage/microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and secondary injury via regulatory T cells after focal ischemia. J Immunol. 2014;192:6009–6019. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Wang H, Li Q, Huang J, Sun X. Modulating autophagy affects neuroamyloidogenesis in an in vitro ischemic stroke model. Neuroscience. 2014;263:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu NH, Weiss HR. Oxy- and carboxyhemoglobin saturation determination in frozen small vessels. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H626–H631. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.2.H626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]