Abstract

Objectives

Salubrious effects of the green coffee bean are purportedly secondary to high concentrations of chlorogenic acid. Chlorogenic acid has a molecular structure similar to bioflavonoids that activate transepithelial Cl- transport in sinonasal epithelia. In contrast to flavonoids, the drug is freely soluble in water. The objective of this study is to evaluate the Cl- secretory capability of chlorogenic acid and its potential as a therapeutic activator of mucus clearance in sinus disease.

Study Design

Basic research

Setting

Laboratory

Subjects and Methods

Chlorogenic acid was tested on primary murine nasal septal epithelial(MNSE)[CFTR+/+ and transgenic CFTR-/-] and human sinonasal epithelial(HSNE)[CFTR+/+ and F508del/F508del] cultures under pharmacologic conditions in Ussing chambers to evaluate effects on transepithelial Cl- transport. Cellular cAMP, phosphorylation of the CFTR regulatory domain(R-D), and CFTR mRNA transcription were also measured.

Results

Chlorogenic acid stimulated transepithelial Cl- secretion [(change in short-circuit current(ΔISC=μA/cm2)] in MNSE(13.1+/-0.9 vs. 0.1+/-0.1, p<0.05) and HSNE(34.3+/-0.9 vs. 0.0+/-0.1, p<0.05). The drug had a long duration until peak effect at 15-30 minutes after application. Significant inhibition with INH-172, as well as absent stimulation in cultures lacking functional CFTR, suggests effects are dependent on CFTR-mediated pathways. However, the absence of elevated cellular cAMP and phosphorylation the CFTR R-D indicates chlorogenic acid does not work through a PKA-dependent mechanism.

Conclusion

Chlorogenic acid is a water soluble agent that promotes CFTR-mediated Cl- transport in mouse and human sinonasal epithelium. Translating activators of mucociliary transport to clinical use provides a new therapeutic approach to sinus disease. Further in vivo evaluation is planned.

Keywords: Transepithelial Ion Transport, Chlorogenic Acid, CFTR, Chronic Sinusitis, Chloride Secretion, Murine Nasal Culture, Sinus Epithelium, Mucociliary Clearance

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) causes significant morbidity and detriment to quality of life for afflicted patients. In the disease cystic fibrosis (CF), CRS is virtually universal. CF is caused by defects in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-regulated anion transporter present on the apical surface of epithelial cells in multiple tissues, including the sinonasal cavities.1 Due to the absence of functional CFTR, airway surface liquid (ASL) depletion results,2 contributing to delayed mucociliary clearance (MCC), bacterial colonization, and severe chronic sinus infections.1 Non-CF patients with CRS have diminished MCC as well, which can be restored once adequate treatment to reestablish healthy mucosa has been provided.3 Recently, a number of laboratories have shown that acquired CFTR dysfunction may cause delayed MCC even in the absence of congenital CFTR mutations and may be a contributing factor in CRS and other disease of MCC such as COPD.4-12 Reduced CFTR function in the nose has also been associated with chronic bronchitis,13 suggesting that CFTR could represent a potential therapeutic target in CRS as well.14-16

Recently, there has been increased interest in bioflavonoids and their derivatives as potential therapeutic activators of CFTR.17,18 Previous findings from our laboratory have demonstrated several flavonoids that enhance Cl- secretion in human sinonasal epithelial cells (HSNE).19-22 One naturally derived molecule that has a similar molecular structure to flavonoids is chlorogenic acid ((3-caffeoylquinic acid)). The widely sought benefits of the green coffee bean are thought to be derived from high concentrations of chlorogenic acid. Salutary effects have been described for a variety of conditions including, diabetes, weight loss, and cancer.23 Whether chlorogenic acid might interact with the CFTR channel in a similar fashion to some flavonoids has not been previously investigated. Furthermore, the water-solubility of chlorogenic acid provides a distinct advantage over flavonoids for in vivo drug delivery that would target acquired defects in CFTR-mediated Cl- secretion. Given the limited treatment options for sinus disease, translating a new class of drugs aimed at restoring the airways primary innate defense against disease (mucociliary transport) represents an exciting therapeutic approach. The objective of this study is to evaluate the Cl- secretory capability of chlorogenic acid and investigate its potential as a therapeutic activator of mucus clearance in sinus disease.

Methods

University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Review Board approval were obtained prior to initiation of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant on a document approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Tissue Culture

Normal sinonasal mucosa was obtained intraoperatively from 5 patients undergoing endoscopic surgery for pituitary tumors, benign sinonasal tumors or cerebrospinal fluid leak repair and 2 cystic fibrosis patients with the F508del/F508del genotype for the establishment of primary cell cultures. Primary sinonasal epithelial cells from humans and nasal septal epithelial cells from CFTR+/+ and CFTR-/- mice were cultured at an air-liquid interface according to previously established protocols.11,12,24-28 All MNSE cells were obtained from congenic C57/BL6 wild type and CFTR-/- mice. Primary nasal epithelial cells were prepared and cultured on collagen coated Costar 6.5-mm-diameter permeable filter supports (Corning, Lowell, MA) submerged in culture media.

Electrophysiology

Short Circuit Current (ISC) Measurements

Transwell inserts (Costar) containing primary monolayers were configured in Ussing chambers (VCC 600; Physiologic Instruments Inc. CA. USA) in order to investigate pharmacologic manipulation of vectorial ion transport. Cell monolayers were continuously analyzed under short circuit conditions following fluid resistance compensation using automatic voltage clamps. Bath solutions for the transwell filters were warmed to 37°C, and each solution continuously gas lifted with 95%O2-5%CO2. Serosal bath solutions contained (in mM): 120 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 3.3 KH2PO4, 0.8 K2HPO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, and 10 glucose that provide a pH of 7.4 under conditions studied here. The solution was adequately buffered to minimize pH change with addition of chlorogenic acid and all experiments performed with a low Cl- gradient. Drugs included amiloride (100 μM) to block sodium transport, chlorogenic acid (1.5 mM), and CFTR(inh)172 (10 μM) to inhibit CFTR-mediated ISC. Forskolin (20 μM) was added after chlorogenic acid to maximally activate CFTR via cAMP/Protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated pathways. Corresponding water (vehicle) control solutions for chlorogenic acid were studied in parallel. The ISC was assessed at one current measurement per second. By convention, a positive deflection in ISC was defined as the net movement of anions in the serosal to mucosal direction. A minimum of 5 wells were tested per condition.

CFTR R-domain phosphorylation and cAMP levels

To evaluate whether chlorogenic acid stimulates CFTR through PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the CFTR regulatory domain (R-D), an ELISA-based detection kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to measure stimulation of cellular cAMP by chlorogenic acid in MNSE cultures, as previously described.18 Direct evaluation of R-D phosphorylation was accomplished using polyclonal NIH-3T3 cells expressing a hemagluttinin (HA)-tagged R-domain. We used the R-domain construct because the large size and glycosylation-sensitive electrophoresis pattern of native CFTR negatively affects the interpretation of mobility shift experiments. Cells were treated with chlorogenic acid (1.5 mM) for 15 minutes, and compared to forskolin (20 μM) as a positive control and water as negative control. Following lysis, equal amounts (50 μg) of total cell lysate were electrophoresed through a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE), and immunoblotted with antibody to the HA tag (Covance, Cumberland, VA). Phosphorylation of the R-domain was visualized as a 2-4 kD shift in migration, as previously described.18

Gene Expression

Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer instructions. To prevent DNA contamination, samples were pretreated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) and column purified. The one-step Applied Biosystems PCR protocol was used to quantify CFTR transcripts with the ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system and six serial dilutions of RNA isolates (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). TaqMan OneStep PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit (ABI) was used for reverse transcription and PCR. Primers for murine CFTR, human CFTR and 18S rRNA were purchased from Assays on Demand (ABI); with assay ID for murine CFTR, Mm00445197_m1; and human CFTR, Hs00357011_m1. The thermocycler conditions were as follows: Stage 1: 48°C for 30 min; Stage 2: 95°C for 10 min; Stage 3: 95°C for 15 sec; Stage 4: 60°C for 1 min; 40 cycles. All CFTR values were normalized to 18S rRNA (from the same sample) according to the Applied Biosystems relative quantification method. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Excel 2010 and GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (La Jolla, Ca) with significance set at P < 0.05. Statistical evaluation utilized unpaired Student t tests for Ussing chamber data and analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test if necessary for cAMP assay and RT-PCR. Data is expressed +/- standard error of the mean.

Results

Chlorogenic acid is a robust Cl- secretagogue

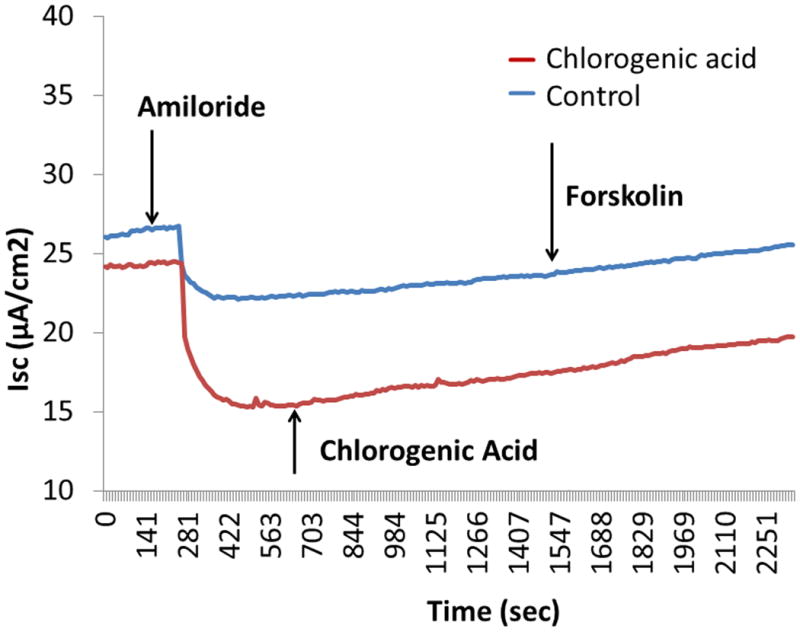

The optimal concentration of chlorogenic acid for stimulating transepithelial Cl- secretion [(change in short-circuit current(ΔISC in μA/cm2)] in MNSE and HSNE was 1.5 mM as determined by dose-response experiments (data not shown). Chlorogenic acid stimulated transepithelial Cl- transport in MNSE (13.1+/-0.9 vs. 0.1+/-0.1 (control), p<0.05) but had a slower onset to peak effect (15 to 30 minutes after application) than usual CFTR activators like forskolin (Figure 1). Interestingly, maximal activation of CFTR with forskolin was significantly greater in cultures incubated with chlorogenic acid than water controls (chlorogenic acid+forskolin; 20.5+/-2.6 vs. control+forskolin; 14.4+/-2.3;p<0.05). Addition of the CFTR blocker INH-172 reduced ISC in a similar fashion [-18.5+/-0.8 vs. -16.1+/-1.5 (control); p<0.05]. Because CFTR-/- MNSE cultures had no response to the drug, stimulation of transepithelial anion secretion is dependent upon intact CFTR-mediated pathways.

Figure 1.

A - Representative Ussing chamber tracings show pharmacologic manipulation of ion transport in murine nasal septal epithelial cultures.

B - Summary data reveals marked activation of Cl− secretion by chlorogenic acid (*p<0.05). Chlorogenic acid-stimulated ΔISC is also greater than water control when CFTR is maximally activated with forskolin in both sets of cultures (*p<0.05). INH-172 also significantly inhibited ΔISC in chlorogenic acid treated monolayers (*p<0.05).

C - CFTR−/− cultures tested with the drug reveal its effects are dependent on CFTR-mediated pathways.

Chlorogenic acid stimulates CFTR-mediated transepithelial Cl- transport in human sinonasal epithelia

Chlorogenic acid significantly increased ΔISC in HSNE cultures (34.1+/-0.3 vs. 0.0+/-0.2 (control), p<0.05) establishing that the agent is a strong Cl− secretagogue in human sinus and nasal epithelium (Figure 2). However, a much larger percentage (>80%) of total ΔISC was stimulated when compared to MNSE indicating the drug may have enhanced activity in human epithelia. The marked increase in total ΔISC with chlorogenic acid + forskolin indicates anion secretion was present in quantities above what would be expected with maximally-activated CFTR in control + forskolin-treated cultures (40.8+/-3.2 vs. 24.5+/-0.8; p<0.05). HSNE cultures derived from patients who lack functional CFTR (F508del/dF508del) exhibited no stimulation of Cl- secretion following treatment with the drug.

Figure 2.

A – Ussing chamber tracings reveal significant ΔISC in human sinonasal epithelium with administration of 1.5 mM chlorogenic acid.

B - Summary data demonstrate increased Cl- transport with forskolin in cultures pre-treated with chlorogenic acid as well as strong inhibition with addition of INH-172 (*p<0.05).

C - Ussing chamber tracings show human (F508del/F508del) monolayers are unresponsive the drug.

Stimulated CFTR-dependent anion transport is independent of cAMP signaling and R-D phosphorylation

PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the CFTR R-D is a critical step in channel activation, but flavonoid compounds (e.g. genistein29) have been shown to act through potentiation of CFTR channel opening rather than activating cAMP-mediated cell signaling pathways. To examine whether chlorogenic acid might activate CFTR via these PKA-dependent pathways, cAMP levels and R-D phosphorylation were assessed. While the cAMP agonist forskolin had markedly increased cAMP levels (p<0.001) and phosphorylation-dependent mobility shift of recombinant CFTR R-D, chlorogenic acid had no detectable effect in either assay (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

MNSE were exposed to forskolin (20 μM), vehicle (water), or 1.5 mM chlorogenic acid for 15 minutes prior to assay. Chlorogenic acid did not increase cAMP compared to vehicle control, while forskolin markedly elevated cAMP.

The drug had no detectable effect on R-domain phosphorylation. A 2–4 kD mobility shift (black arrow) is seen following treatment with forskolin.

Delayed onset of activity is not secondary to increased mRNA transcription

To rule out the possibility that the drug's delayed activity could be attributable to increased mRNA transcription, quantitative RT-PCR for CFTR was performed. CFTR mRNA levels remained unchanged following incubation with the drug (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR shows chlorogenic acid has no significant effect on CFTR gene expression.

Discussion

Bioflavonoids have garnered significant attention over the last decade due to a variety of health benefits and favorable biological activities. Pharmacologic activation of the CFTR channel to potentiate mucociliary clearance in CF patients is an active area of research, with previous findings from our laboratory demonstrating several flavonoid compounds that increase ion transport via the CFTR channel.30-33 However, bioflavonoids are insoluble in water and thus other solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) are required to administer the agents as topical therapeutics. Known side effects of DMSO include headaches, burning and itching, skin contact allergic reactions, and the solvent is thought to augment the effects of steroids, blood thinners, cardiac medicines, sedatives, and other drugs.34 Thus, water soluble potentiators of CFTR that have similar methods of action have valuable potential for both oral and topical delivery.

In the current study, we evaluated the ability of chlorogenic acid to activate CFTR-dependent Cl- transport in primary cell culture models of sinonasal epithelium. Chlorogenic acids have been found to attenuate oxidative stress,35 inhibit enzymes associated with lipid metabolism,36 and ameliorate the tumor promoting activity of phorbol esters.37 Despite similarities to flavonoid structure, no previous studies have investigated the effects of the drug on transepithelial ion transport. Importantly, chlorogenic acid has been shown to modulate ion channels in other cells, specifically, voltage gated potassium channels in sensory neurons.38 Our findings indicate chlorogenic acid (1.5 mM) robustly stimulates CFTR in upper airway cell monolayers, albeit with a longer duration to peak effect than flavonoids and other drugs. Inhibition with INH-172 in CFTR+/+ epithelia and lack of transepithelial Cl- secretion in CFTR-/- MNSE and dF508/dF508 HSNE monolayers suggest the action of chlorogenic acid is dependent upon the presence of functional CFTR. However, stimulation of vectorial anion transport was increased over what was seen with maximally-activating forskolin alone. Thus, the drug may stimulate anion transport by other means as well (e.g. basolateral membrane K+ channel activation) to increase the driving force through CFTR-mediated pathways.

Further exploration of the drug's mechanism of action was performed to determine whether increased CFTR-mediated Cl- secretion could be explained by triggering cellular cAMP signaling and subsequent activation of the CFTR R-D. After exposure to chlorogenic acid, there was no elevation of cellular cAMP or phosphorylation of the R-domain according to gel shift assay. Subsequent investigations regarding the agent's ability to potentiate CFTR channel opening were not successful using excised inside-out patch clamp techniques because of the drug's delayed effect and inability to hold a patch for the duration of the experiments (data not shown). There was also no increase in gene expression with exposure to chlorogenic acid. Additional tests will be required to determine the precise mechanism of action underlying robust stimulation of Cl- secretion conferred by this agent.

Conclusion

In summary, chlorogenic acid activates CFTR-mediated Cl- secretion in murine and human sinonasal epithelium. Using a water soluble activator of transepithelial Cl- transport to enhance MCC could be potentially beneficial in individuals with CRS. Further in vivo evaluation in human subjects is planned.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Bradford A. Woodworth, MD - NIH/NHLBI (1K08HL107142-05); Eric J. Sorscher, MD - NIH/NIDDK (5P30DK072482-04)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Eric Sorscher, MD, and Bradford Woodworth, MD are inventors on a patent pending regarding the use of chloride secretagogues for therapy of sinus disease (35 U.S.C. n111(b) and 37 C.F.R n.53 (c)) in the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

References

- 1.Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ. Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 12;352(19):1992–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsui H, Grubb BR, Tarran R, et al. Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell. 1998 Dec 23;95(7):1005–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asai K, Haruna S, Otori N, Yanagi K, Fukami M, Moriyama H. Saccharin test of maxillary sinus mucociliary function after endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2000 Jan;110(1):117–122. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200001000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreindler JL, Jackson AD, Kemp PA, Bridges RJ, Danahay H. Inhibition of chloride secretion in human bronchial epithelial cells by cigarette smoke extract. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005 May;288(5):L894–902. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00376.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sloane PA, Shastry S, Wilhelm A, et al. A pharmacologic approach to acquired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator dysfunction in smoking related lung disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantin AM, Hanrahan JW, Bilodeau G, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function is suppressed in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 May 15;173(10):1139–1144. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1330OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bomberger JM, Ye S, Maceachran DP, et al. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin that hijacks the host ubiquitin proteolytic system. PLoS Pathog. 2011 Mar;7(3):e1001325. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacEachran DP, Ye S, Bomberger JM, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted protein PA2934 decreases apical membrane expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Infect Immun. 2007 Aug;75(8):3902–3912. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander NS, Blount A, Zhang S, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulation by the tobacco smoke toxin acrolein. Laryngoscope. 2012 Jun;122(6):1193–1197. doi: 10.1002/lary.23278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blount A, Zhang S, Chestnut M, et al. Transepithelial ion transport is suppressed in hypoxic sinonasal epithelium. Laryngoscope. 2011 Sep;121(9):1929–1934. doi: 10.1002/lary.21921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virgin FW, Azbell C, Schuster D, et al. Exposure to cigarette smoke condensate reduces calcium activated chloride channel transport in primary sinonasal epithelial cultures. Laryngoscope. 2010 Jul;120(7):1465–1469. doi: 10.1002/lary.20930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen NA, Zhang S, Sharp DB, et al. Cigarette smoke condensate inhibits transepithelial chloride transport and ciliary beat frequency. Laryngoscope. 2009 Nov;119(11):2269–2274. doi: 10.1002/lary.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dransfield MT, Wilhelm AM, Flanagan B, et al. Acquired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator dysfunction in the lower airways in COPD. Chest. 2013 Aug;144(2):498–506. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Skinner D, Hicks SB, et al. Sinupret Activates CFTR and TMEM16A-Dependent Transepithelial Chloride Transport and Improves Indicators of Mucociliary Clearance. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Blount AC, McNicholas CM, et al. Resveratrol enhances airway surface liquid depth in sinonasal epithelium by increasing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator open probability. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander NS, Hatch N, Zhang S, et al. Resveratrol has salutary effects on mucociliary transport and inflammation in sinonasal epithelium. Laryngoscope. 2011 Jun;121(6):1313–1319. doi: 10.1002/lary.21798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer H, Illek B. Activation of the CFTR Cl- channel by trimethoxyflavone in vitro and in vivo. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22(5-6):685–692. doi: 10.1159/000185552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyle LC, Fulton JC, Sloane PA, et al. Activation of CFTR by the Flavonoid Quercetin: Potential Use as a Biomarker of {Delta}F508 CFTR Rescue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009 Dec 30; doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0281OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conger BT, Zhang S, Skinner D, et al. Comparison of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) and Ciliary Beat Frequency Activation by the CFTR Modulators Genistein, VRT-532, and UCCF-152 in Primary Sinonasal Epithelial Cultures. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2013 Aug 1;139(8):822–827. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Smith N, Schuster D, et al. Quercetin increases cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-mediated chloride transport and ciliary beat frequency: Therapeutic implications for chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011 Sep-Oct;25(5):307–312. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virgin F, Zhang S, Schuster D, et al. The bioflavonoid compound, sinupret, stimulates transepithelial chloride transport in vitro and in vivo. Laryngoscope. 2010 May;120(5):1051–1056. doi: 10.1002/lary.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azbell C, Zhang S, Skinner D, Fortenberry J, Sorscher EJ, Woodworth BA. Hesperidin stimulates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-mediated chloride secretion and ciliary beat frequency in sinonasal epithelium. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Sep;143(3):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng S, Cao J, Feng Q, et al. Roles of chlorogenic acid on regulating glucose and lipid metabolism: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;801457 doi: 10.1155/2013/801457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhargave G, Woodworth BA, Xiong G, Wolfe SG, Antunes MB, Cohen NA. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 channel expression in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2008 Jan-Feb;22(1):7–12. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodworth BA, Antunes MB, Bhargave G, et al. Murine nasal septa for respiratory epithelial air-liquid interface cultures. Biotechniques. 2007;43(2):195–204. doi: 10.2144/000112531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodworth BA, Antunes MB, Bhargave G, Palmer JN, Cohen NA. Murine tracheal and nasal septal epithelium for air-liquid interface cultures: A comparative study. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(5):533–537. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodworth BA, Tamashiro E, Bhargave G, Cohen NA, Palmer JN. An in vitro model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on viable airway epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(3):234–238. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Fortenberry JA, Cohen NA, Sorscher EJ, Woodworth BA. Comparison of vectorial ion transport in primary murine airway and human sinonasal air-liquid interface cultures, models for studies of cystic fibrosis, and other airway diseases. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009 Mar-Apr;23(2):149–152. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran O, Zegarra-Moran O. A quantitative description of the activation and inhibition of CFTR by potentiators: Genistein. FEBS Lett. 2005 Jul 18;579(18):3979–3983. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander N, Hatch, N, Zhang, S, et al. Reveratrol has salutary effects on mucociliary transport and inflammation in sinonasal epithelium. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(6):1313–1319. doi: 10.1002/lary.21798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azbell C, Zhang, S, Skinner, D, et al. Hesperidin stimulates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-mediated chloride secretion and ciliary beat frequency in sinonasal epithelium. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(3):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conger B, Zhang, S, Skinner, D, et al. Comparison of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and ciliary beat frequency activation by the CFTR Modulators Genistein, VRT-532, and UCCF-152 in primary sinonasal epithelial cultures. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(8):822–827. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virgin F, Zhang, S, Schuster, D, et al. The bioflavonoid compound, sinupret, stimulates transepithelial chloride transport in vitro and in vivo. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(5):1051–1056. doi: 10.1002/lary.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. [Accessed Augst 20]; http://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatmentsandsideeffects/complementaryandalternativemedicine/pharmacologicalandbiologicaltreatment/dmso;

- 35.Zhao Z, Shin HS, Satsu H, Totsuka M, Shimizu M. 5-caffeoylquinic acid and caffeic acid down-regulate the oxidative stress- and TNF-alpha-induced secretion of interleukin-8 from Caco-2 cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2008 May 28;56(10):3863–3868. doi: 10.1021/jf073168d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng S, Cao J, Feng Q, Peng J, Hu Y. Roles of chlorogenic Acid on regulating glucose and lipids metabolism: a review. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2013;2013:801457. doi: 10.1155/2013/801457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng CJ, Yen GC. Chemopreventive effects of dietary phytochemicals against cancer invasion and metastasis: phenolic acids, monophenol, polyphenol, and their derivatives. Cancer treatment reviews. 2012 Feb;38(1):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang YJ, Lu XW, Song N, et al. Chlorogenic acid alters the voltage-gated potassium channel currents of trigeminal ganglion neurons. International journal of oral science. 2014 Dec;6(4):233–240. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2014.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]