Abstract

♦ Background:

Health-care systems must attempt to provide appropriate, high-quality, and economically sustainable care that meets the needs and choices of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). France offers 9 different modalities of dialysis, each characterized by dialysis technique, the extent of professional assistance, and the treatment site. The aim of this study was 1) to describe the various dialysis modalities in France and the patient characteristics associated with each of them, and 2) to analyze their regional patterns to identify possible unexpected associations between case-mixes and dialysis modalities.

♦ Methods:

The clinical characteristics of the 37,421 adult patients treated by dialysis were described according to their treatment modality. Agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis was used to aggregate the regions into clusters according to their use of these modalities and the characteristics of their patients.

♦ Result:

The gradient of patient characteristics was similar from home hemodialyis (HD) to in-center HD and from non-assisted automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) to assisted continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). Analyzing their spatial distribution, we found differences in the patient case-mix on dialysis across regions but also differences in the health-care provided for them. The classification of the regions into 6 different clusters allowed us to detect some unexpected associations between case-mixes and treatment modalities.

♦ Conclusions:

The 9 modalities of treatment available make it theoretically possible to adapt treatment to patients' clinical characteristics and abilities. However, although we found an overall appropriate association of dialysis modalities to the case-mix, major inter-region heterogeneity and the low rate of peritoneal dialysis (PD) and home HD suggest that factors besides patients' clinical conditions impact the choice of dialysis modality. The French organization should now be evaluated in terms of patients' quality of life, satisfaction, survival, and global efficiency.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, health-care planning, case mix, agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis

Health-care systems must seek to provide appropriate, high-quality, and economically sustainable care that meets the needs and desires of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). It should be designed to improve quality of care and patient well-being. Renal replacement therapy can be provided by renal transplantation or by 1 of the 2 main dialysis techniques (peritoneal dialysis [PD] and hemodialysis [HD]). End-stage renal disease care in France takes place in 1,003 dialysis units in 839 different locations owned by 341 different health-care providers (9% public university hospitals, 29% public non-university hospitals, 29% private non-profits, and 33% private for-profit units), and 34 university hospital centers that perform transplantation. The prevalence of treated ESRD in France in 2012 was 1,127 per million inhabitants, among the highest rates in Europe, close to those observed in Belgium, Austria, and Spain (1). Overall, 44% of these patients live with a renal graft, 52% are treated by HD, and 4% by PD. Dialysis activity is organized and regulated regionally (22 metropolitan regions and 5 overseas territories), and transplantation activities at a supraregional level (7 areas). Regional health organization schemes set targets for 5 years and determine the distribution of care between the different treatment modalities, taking into account the needs, available resources, and the conditions for access to these modalities within the territories.

In 2002, in France, both legislative and regulatory policies were developed in a broad consultation with professionals to monitor the practice of dialysis. These brought breakthroughs for patients, by improving the quality and safety of care and maximizing choices, for professionals by clarifying the previously undefined modalities of treatment, and for the government and health agencies, by developing an innovative authorization regime and tools to map supply as closely as possible to patient demand. The aim of these regulations was to meet the following requirements: to guarantee free choice for patients, provide appropriate and high-quality care, preserve local health services and individualized care, and ensure continuity of care.

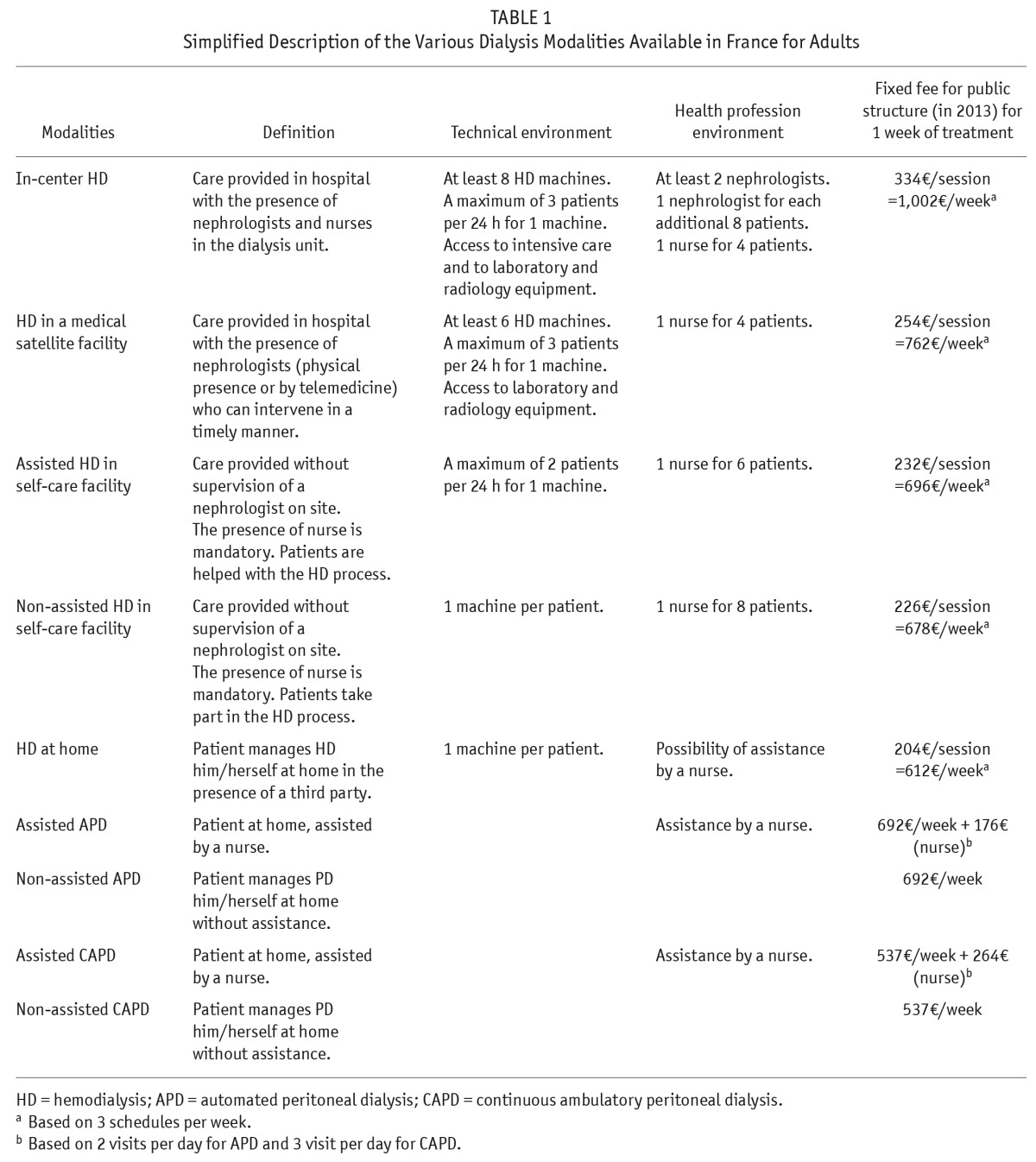

Consequently, 9 different modalities are offered in France, each characterized by dialysis technique, the extent of professional assistance, and the treatment site (Table 1). Regardless of the environment of the dialysis unit (hospital-based, satellite or self-care facilities, home dialysis) or the type of provider (university, public, private not for profit, private for-profit), each dialysis facility is required to provide medical services 24 hours a day and to have back-up available at an in-center dialysis unit. In fact, patients can be divided into 2 main categories: those who want to be in a professional environment during the procedure, and others who prefer the attendance of family members, at home. Patients preferring dialysis in medical institutions have 3 choices: in-center, medical satellite facilities, and self-care facilities. The final decision is based on the patient's stability, potential risk of complications, and capacity and willingness to be involved in the treatment process. For patients preferring home treatment, several treatment options are also available: HD or PD (including continuous ambulatory PD [CAPD] and automated PD [APD]), with or without a nurse's assistance, depending on their capacity for involvement in the treatment process. However, despite this wide range of choices, in-center HD is still the preferred modality of treatment, and PD and non-assisted HD modalities are not close to adequately used yet (1).

TABLE 1.

Simplified Description of the Various Dialysis Modalities Available in France for Adults

The case-mix is quite heterogeneous across French regions (2) as is the use of dialysis modalities, in particular the use of PD (3,4) and non-assisted HD modalities. The aim of this study was 1) to describe the various dialysis modalities in France and the patient characteristics associated with each of them, and 2) to analyze their regional patterns to identify possible unexpected associations of case-mixes and dialysis modalities.

Methods

The Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (REIN) registry includes all ESRD patients on renal replacement therapy—either dialysis or transplantation—in France. Patients with a diagnosis of acute kidney failure are excluded, i.e., those who recover all or some renal function within 45 days or are diagnosed as such by experts when they die before 45 days. The details of its organizational principles and quality control are described elsewhere (5). This study included all patients aged 18 years or older treated with dialysis on December 31, 2012, in the 22 metropolitan regions of France. The 5 overseas regions and Corsica were excluded because of their specific case-mixes and particularities. Patients under the age of 18 years were excluded because they are mainly treated in specific pediatric in-center units.

Baseline information included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), mobility status (walks without help, needs assistance for transfers, or totally dependent for transfers), and the following comorbidities: diabetes (type 1 or 2), congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association stages I – IV), peripheral vascular disease (Leriche classification stages I – IV), coronary heart disease with or without history of myocardial infarction, stroke or transient ischemic attack, chronic respiratory disease, dysrhythmia, active malignancy, cirrhosis, and viral hepatitis. Patients were grouped according to their treatment modality on December 31, 2012, into the 9 categories described above, defined identically in each region.

The clinical characteristics of the patients receiving each of these 9 different dialysis modalities were described and compared by logistic regression, after adjustment for age and gender and comorbidities when appropriate. Heterogeneity of the regions concerning case-mix and treatment modalities was analyzed by comparing the distribution of some items across regions and expressed as medians and their interquartile ranges (IQR).

We used agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis (AHCA) to aggregate the 22 metropolitan regions into clusters according to their use of the different modalities and their patients' characteristics (median age, percentage of patients with diabetes, cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities, and mobility) (6). Agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis is a rigorous methodological tool that can be used to highlight multidimensional relations and has been used extensively in other research fields (7–9). A Euclidian metric and Ward's minimum variance criterion were used as data parameters for the AHCA. In Ward's minimum-variance method, the distance between 2 clusters is the ANOVA sum of squares between the 2 clusters added up over all the variables. At each generation, the within-cluster sum of squares is minimized over all partitions obtainable by merging 2 clusters from the previous generation. Ward's method tends to join clusters with a small number of observations, and it is strongly biased toward producing clusters with roughly the same number of observations. To strengthen the results by Ward's method, we compared them with the average linkage cluster analysis method. In average linkage, the distance between 2 clusters is the average distance between pairs of observations, 1 in each cluster. Average linkage tends to join clusters with small variances, and it is slightly biased toward producing clusters with the same variance. We also compared the results of the clustering after changing the order of the regions in the data set. The number of clusters was determined to maximize the inter-class variance and minimize the intra-class variance and to obtain a small value of the pseudo t2 statistic and a larger pseudo t2 for the next cluster fusion. All statistics were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA), and results are presented in maps produced by Philcarto 5.69 (http://philgeo.free.fr) and Adobe Illustrator CS5 (Adobe Systems Incorporated, CA, USA).

Results

Study of Patient Characteristics by Dialysis Modality

On December 31, 2012, 40,752 adults (age ≥ 18 years) were being treated by dialysis in France. Missing data for treatment modality resulted in the exclusion of 360 patients; another 293 were excluded because they were in training units before transfer to home PD or self-care facility HD (and thus unclassifiable), and 2,676 lived in overseas regions. Overall, 37,421 patients were analyzed, 35,116 of them on HD (94%) and 2,305 on PD (6%).

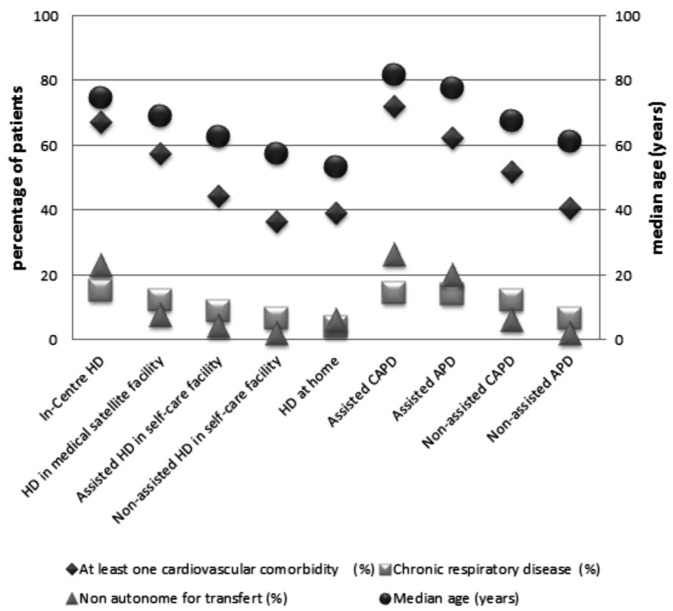

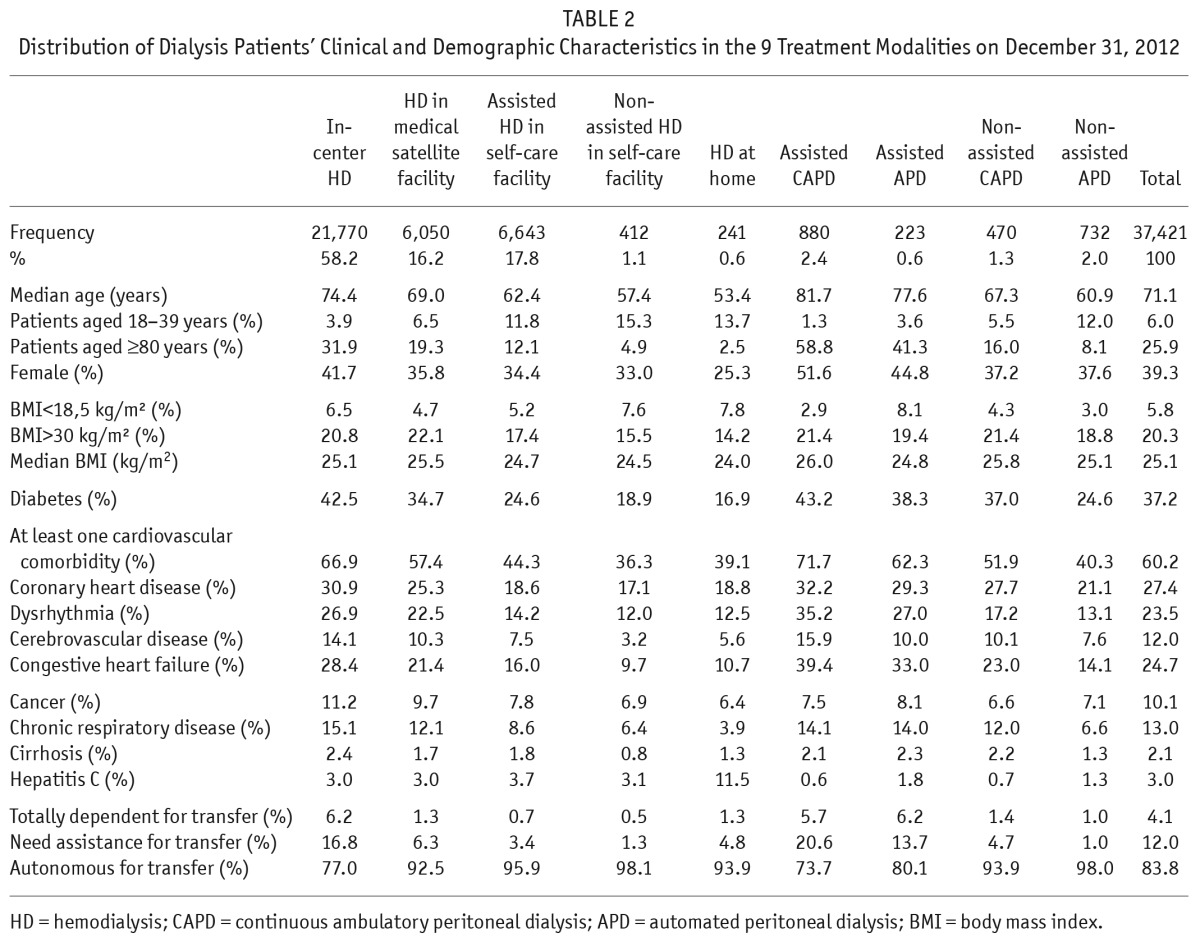

Table 2 and Figure 1 report the distribution of patients' characteristics by modality. In-center HD was the most frequent modality (58%). Non-assisted modalities accounted for less than 2% of the HD patients and half the PD patients, and home dialysis for 6.7% of all patients, 10% with HD, 90% with PD. Only 6% of all patients used any modality of PD. The median age was high in assisted PD patients and highest for assisted CAPD patients (81.7 years); overall it was 70.8 years for men and 71.9 for women. Women had fewer comorbidities: 54% had at least 1 cardiovascular comorbidity, compared with 63% of men. Nonetheless, the percentage of women in each modality increased along the continuum from the autonomous to the more assisted modalities, for both HD and PD. The probability of treatment by assisted or supervised (compared with autonomous) modalities (PD or HD) remained higher for women, even after adjustment for age, comorbidity, and mobility status.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Dialysis Patients' Clinical and Demographic Characteristics in the 9 Treatment Modalities on December 31, 2012

Figure 1 —

Median age and percentage of patients with cardiovascular and respiratory comorbidities or mobility problems, according to the 9 treatment modalities, for patients on dialysis on December 31, 2012. HD = hemodialysis; CAPD = continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; APD = automated peritoneal dialysis.

As expected, severely ill patients with the poorest mobility scores (totally dependent for transfer) were treated mainly by in-center HD and assisted PD and account for less than 2% of patients in the other modalities. Obesity was not associated with treatment modality, even morbid obesity (BMI > 45 kg/m2). The percentage of patients with comorbidities increased from autonomous to supervised or assisted modalities, along the following continuum of severity: home HD and non-assisted HD in self-care facilities, non-assisted APD, assisted HD in self-care facilities, non-assisted CAPD, HD in medical satellite facilities, assisted APD, in-center HD, and assisted CAPD. The youngest population was that using home HD (median age 53.4 years), and its comorbidity level was slightly higher than that of the population using non-assisted HD in self-care facilities. Even after taking age, gender, comorbidities, and mobility into account, hepatitis C-positive patients were more likely to be receiving HD at home than in a self-care facility.

Regional Variations in Case-Mix and Dialysis Modality Use

The percentage of diabetic patients and patients with at least 1 cardiovascular comorbidity varied from 27% to 48% (median 37%, IQR 34% – 39%) and from 48% to 72% (median 62%, IQR 60% – 66%) respectively, across regions. Median age varied from 67 years to 74 years (median 71.9 years, IQR 70.5 – 73.4). Regional patterns of those clinical characteristics are presented in the supplemental data (Figure S1).

Assisted PD is mainly used in northeastern France; the percentage of patients treated with this modality varied from 0.4% to 10.9% (median 3%, IQR 2% – 4.5%) across regions. Non-assisted PD is more widely used, at higher levels from 1% to 7.7% (median 3.7%, IQR 2.2% – 5.4%). Self-care HD facilities are mainly used in southwestern France and in the North; the percentage of patients treated with this modality varies from 2.9% to 37.5% (median 17.8%, IQR 15% – 21.8%). The regional patterns of those modalities are presented in the supplemental data (Figure S2).

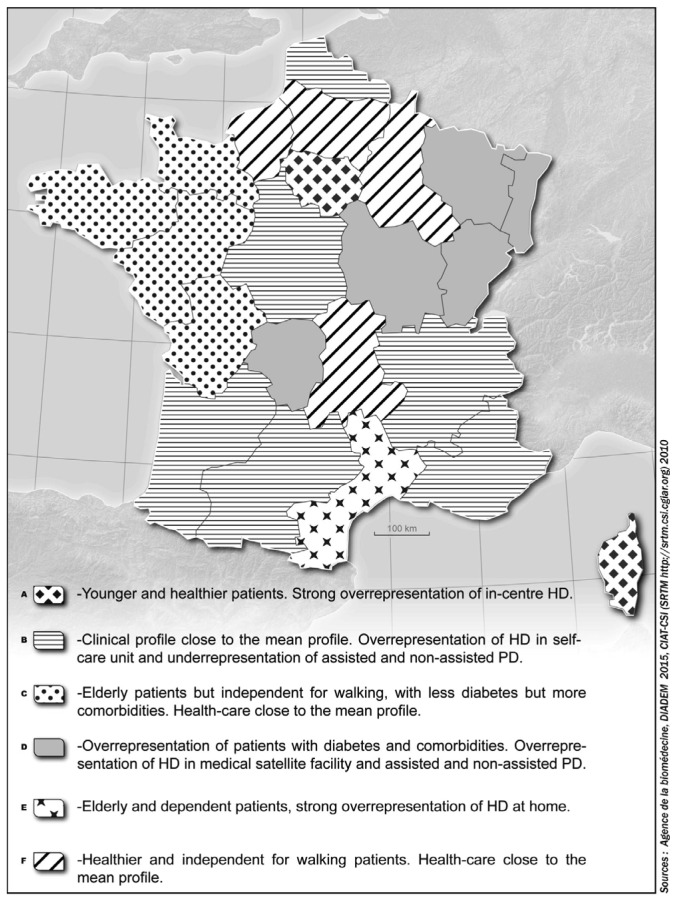

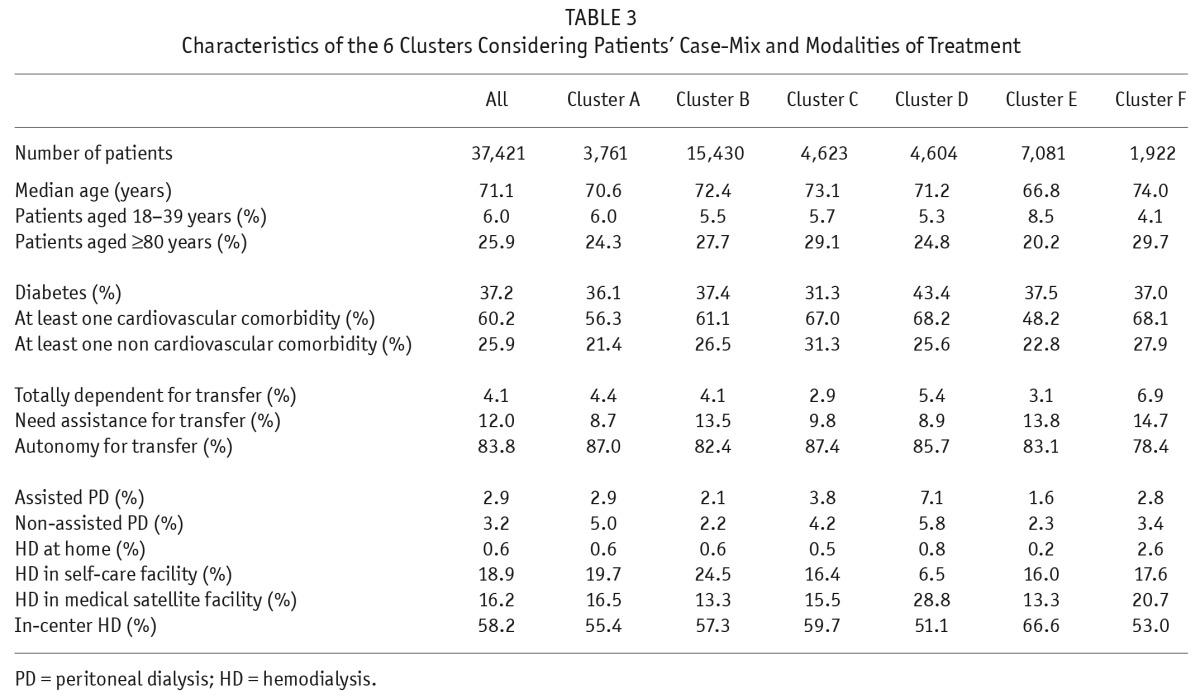

The geographic regions were classified in 6 different clusters according to case-mixes and treatment modalities (the dendogram is presented in the Supplemental data Figure S3). Average linkage yielded the same clusters as Ward's method, with 57% of the total variance inter-group. Table 3 describes the mean characteristics of each cluster considering case-mix and treatment modality, and Figure 2 combines those data on a map to show the spatial patterns of the 6 clusters. Cluster F, including northern regions, and cluster C, including eastern regions, have similar profiles around the mean for the distribution of treatment modalities, but in cluster F patients have fewer comorbidities, while in cluster C patients are older with higher comorbidity rates. Cluster B, including mainly regions in the south, has a profile around the mean for case-mix and a high percentage of patients in self-care facilities (24.5%). Northeastern France, cluster D, is characterized by a higher number of patients on PD (13%) and in medical satellite facilities (29%) and also by more patients with diabetes and cardiovascular comorbidities. Cluster A is mainly represented by the Paris metropolitan region (Ile de France) where patients are younger and have fewer cardiovascular comorbidities, but it nonetheless has a high percentage of patients in in-center HD. Cluster E is characterized by a higher percentage of patients using HD at home than other regions (although only 2.6%) and by elderly patients with cardiovascular comorbidities.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the 6 Clusters Considering Patients' Case-Mix and Modalities of Treatment

Figure 2 —

Representation of the clusters of regions according to the hierarchical classification including case-mix and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) treatment modality. HD = hemodialysis; PD = peritoneal dialysis.

Discussion

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ESRD patients in France at the end of 2012, their dialysis modalities, and the relation between these modalities and the case mix. It also illustrates the underuse of home dialysis (PD and HD) and confirms major regional heterogeneity in modality use in France, not explained by the regional case-mix differences.

Patient Profiles and Treatment Modalities

Despite the low overall use of PD, each PD modality was successfully used, with non-assisted APD reserved for the most mobile patients with few comorbidities, and assisted CAPD for the most severely ill, least mobile patients (10). The same case-mix gradient was seen for HD from home to in-center HD at a globally lower level of severity.

This study shows that comorbidity and age are not the main determinants of the choice of dialysis technique but rather that they affect the choice of modality of treatment. Assistance by nurses makes treatment at home possible for very old patients (10–12). Home HD patients had slightly more cardiovascular comorbidities than patients in non-assisted self-care facilities; this may explain why 30% of the patients at home have daily HD (i.e., more than 4 sessions per week). The optimal dialysis modality for ESRD patients with diabetes or obesity remains controversial (3,13–17). We found here that the frequency of obesity was similar among PD and HD patients, as was the percentage of diabetes. A previous study of 10,815 incident patients who started dialysis from 2002 through 2005 in 13 French regions showed that PD was chosen significantly less often for obese and diabetic patients (3). This discrepancy between incident and prevalent patients might be explained by the transfer to transplantation of the healthiest patients, while prevalent patients with diabetes and obesity tend to remain on dialysis. The higher frequency of congestive heart failure in patients on assisted PD may be explained by the lower hemodynamic variation of PD (18,19), although higher mortality on PD for those patients has been suggested (20). The frequency of chronic respiratory disease was similar for both techniques, although PD may not be considered an appropriate first-line treatment (21).

Neither comorbidities nor frailty explained why our analyses showed that women are treated more frequently with assisted or supervised modalities. Further studies are needed to explore non-medical factors that influence women's choices. These factors may include social support (22) or women's wishes to minimize the intrusiveness of dialysis on quality of life, or their perception of autonomy, values, and sense of self (23).

Regional Heterogeneity

Although we found an overall appropriate association of dialysis modalities to the case-mix, major inter-regional heterogeneity and the low rate of PD and home HD suggest that factors besides patients' clinical condition affect the choice of the dialysis modality. Although all 9 modalities are widely available in all regions (Figure S2), the choice of dialysis modality appears to be guided not only by patients' characteristics, but also by regional specificities. Regions can accordingly be classified by how their use of dialysis modalities matches their case-mix. For example, in this study we were able to identify regions that favor highly assisted and thus more expensive modalities, although they have younger patients with fewer comorbidities (cluster A). On the other hand, regions in cluster B have patients with a closer-to-average profile but have a higher percentage of patients in self-care facilities. In cluster D, the percentage of patients treated by in-center HD is the lowest, yet the prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients in those regions is the highest of the 6 clusters.

Several non-medical factors may play a role in this regional heterogeneity. In France in 2012, the median travel time from home to a dialysis center for patients not treated at home was 20 minutes; 7.5% of the patients had trips longer than 45 minutes. The geographical configuration of some regions may have resulted in the organization of renal care designed to avoid long trips to a HD center and to reduce transportation costs. Until recently, only small self-care facilities were developed in those less accessible areas, available only for relatively healthy and autonomous patients. Medical satellite facilities combined with telemedicine are now allowed and are gradually spreading. Therefore, nearby HD centers should also be accessible to more frail patients. This new organization may affect renal care organization and recommendations for patients. Nonetheless, the financial viability of this organization remains to be demonstrated.

This relatively good territorial coverage may be one explanation for the low use of PD in France, where the issue of transport may be less crucial than in some other countries. Two previous French studies have already shown that PD utilization across France is heterogeneous (3,4). The lack of nurses available for patient care, low reimbursement of PD, limited training, and hospital care facilities providing HD were the main barriers limiting PD utilization in the survey by Bouvier et al. (4). They concluded, however, that the regional discrepancies regarding PD utilization seem to be linked mainly to nephrologists' opinions about PD. Such a survey might usefully be extended to the 9 modalities of treatment used in France. As well, the decreasing number of nephrologists in some regions may be incompatible with the regulatory requirements of quality and safety of care and may limit the development of some modalities. Although the reimbursement level of the different modalities of dialysis is defined according to production costs, the fixed fee for in-center HD may be more attractive for the dialysis units (24). Therefore, this modality may be recommended by providers to ensure the financial viability of the facilities.

The French Model: Limitations and Advantages

In France, patients with similar clinical characteristics are offered several treatment modalities, depending on their wishes and their ability to manage part or all of their treatment. This diversified supply theoretically allows patients and professionals to adapt dialysis treatment to circumstances over time. A major goal is to take into account patients' wishes as much as possible in the decision process. Patients have high expectations for accurate information about their options when choosing dialysis treatment (25). When they have the opportunity to make choices before starting renal replacement treatment, they tend to favor unassisted and home dialysis (26–28). The analysis of the variability of practices raises questions on the effectiveness, equity, and quality of the care provided. The very low rate of PD and the very high rate of in-center HD raise concerns about the reality of the choice left to the patients and the quality of the information given by the professionals. The absence of consensus and the lack of guidelines based on patient characteristics result in different interpretations and diverse medical practices in the French regions, especially in view of the wide range of choices. The aim and the point of analyzing the variability of ESRD care is to understand what differences are justified by patients' clinical and other needs and which practices are inappropriate or inefficient.

Another concern is the cost of the French model, especially because in-center HD, the most widely used modality, is also the most expensive and because the maintenance of all 9 dialysis modalities in every region can be expensive. Specific analyses are needed to assess the budgetary impact of this diversity. Comparative assessments of the effectiveness and cost of different dialysis treatments have been published (29–35). But those studies compared techniques only pairwise, and they do not take into account the potential for treatment changes over a lifetime. They are certainly not designed to evaluate the effectiveness of an organization that provides 9 modalities of treatment among which patients can transfer. We therefore propose promoting studies based on patients' trajectories (36,37). Such a study is now needed in France to evaluate the current organization and the ways of optimizing it.

A wide choice to enable close matching of treatment modalities to patients' needs may offer better care. On the other hand individualizing 9 separate modalities may strongly complicate the management of dialysis facilities and the reimbursement process as well as fragment competences (38). The continuous flow of patients from one modality to another according to their clinical course may also be confusing, not only for patients and health professionals, but also for the agencies responsible for documentation and reimbursement.

The principal limitation of this study is that it describes practices without information about the decision process, in particular, the role of patients' choices and non-medical factors. A major strength of this study is that it is based on a large unselected population including all prevalent dialysis patients from the 22 regions of metropolitan France. Secondly, we used an interesting tool that allowed us to detect some unexpected associations between case-mixes and treatment modalities that require further investigation.

In conclusion, France has made the choice to provide 9 individualized modalities of treatment. This makes it theoretically possible to adapt treatment to patients' clinical characteristics and abilities. However, although we found an overall appropriate association of dialysis modalities to case-mix, major inter-region heterogeneity and the low rate of PD and home HD suggest that factors besides patients' clinical conditions affect the choice of dialysis modality. This French organization should now be evaluated in terms of its global efficiency and patients' quality of life, satisfaction, and survival.

Disclosures

Tamar Phirtskhalaishvili received a grant from the ERA-EDTA Research Initiatives Department (ERA STF 154-2013).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all registry participants, especially the nephrologists and professionals who collected the data and conducted the quality control. The dialysis centers participating in the registry are listed in the annual report: http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/Le-programme-REIN.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at www.pdiconnect.com

REFERENCES

- 1. ERA EDTA registry ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report 2011. Academic Medical Center, Department of Medical Informatics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. REIN registry Rapport annuel REIN 2012. http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/Le-programme-REIN; 2014.

- 3. Couchoud C, Savoye E, Frimat L, Ryckelynck JP, Chalem Y, Verger C. Variability in case mix and peritoneal dialysis selection in fifty-nine French districts. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28(5):509–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouvier N, Durand PY, Testa A, Albert C, Planquois V, Ryckelynck JP, et al. Regional discrepancies in peritoneal dialysis utilization in France: the role of the nephrologist's opinion about peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24(4):1293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Couchoud C, Stengel B, Landais P, Aldigier JC, de Cornelissen F, Dabot C, et al. The renal epidemiology and information network (REIN): a new registry for end-stage renal disease in France. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21(2):411–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benzécri JP. Correspondence analysis handbook. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moran WP, Zhang J, Gebregziabher M, Brownfield EL, Davis KS, Schreiner AD, et al. Chaos to complexity: leveling the playing field for measuring value in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract 2015. [epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clatworthy J, Buick D, Hankins M, Weinman J, Horne R. The use and reporting of cluster analysis in health psychology: a review. Br J Health Psychol 2005; 10(Pt 3):329–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alonso-Moran E, Orueta JF, Esteban JI, Axpe JM, Gonzalez ML, Polanco NT, et al. Multimorbidity in people with type 2 diabetes in the Basque Country (Spain): Prevalence, comorbidity clusters and comparison with other chronic patients. Eur J Intern Med 2015; 26(3):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lobbedez T, Moldovan R, Lecame M, Hurault de LB, El Haggan W, Ryckelynck JP. Assisted peritoneal dialysis. Experience in a French renal department. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26(6):671–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castrale C, Evans D, Verger C, Fabre E, Aguilera D, Ryckelynck JP, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in elderly patients: report from the French Peritoneal Dialysis Registry (RDPLF). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25(1):255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Genestier S, Meyer N, Chantrel F, Alenabi F, Brignon P, Maaz M, et al. Prognostic survival factors in elderly renal failure patients treated with peritoneal dialysis: a nine-year retrospective study. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30(2):218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biesenbach G, Pohanka E. Dialysis in diabetic patients: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Pros and cons. Minerva Urol Nefrol 2012; 64(3):173–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Locatelli F, Pozzoni P, Del Vecchio L. Renal replacement therapy in patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15(Suppl 1):S25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van LS, Veys N, Verbeke F, Vanholder R, Van BW. The fate of older diabetic patients on peritoneal dialysis: myths and mysteries and suggestions for further research. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27(6):611–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Unal A, Hayri SM, Kocyigit I, Elmali F, Tokgoz B, Oymak O. Does body mass index affect survival and technique failure in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis? Pak J Med Sci 2014; 30(1):41–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Couchoud C, Bolignano D, Nistor I, Jager KJ, Heaf J, Heimburger O, et al. Dialysis modality choice in diabetic patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review of the available evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 30(2):310–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nunez J, Gonzalez M, Minana G, Garcia-Ramon R, Sanchis J, Bodi V, et al. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and clinical outcomes in patients with refractory congestive heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2012; 65(11):986–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gotloib L, Fudin R, Yakubovich M, Vienken J. Peritoneal dialysis in refractory end-stage congestive heart failure: a challenge facing a no-win situation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20(Suppl 7):vii32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sens F, Schott-Pethelaz AM, Labeeuw M, Colin C, Villar E. Survival advantage of hemodialysis relative to peritoneal dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease and congestive heart failure. Kidney Int 2011; 80(9):970–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miskulin DC, Meyer KB, Athienites NV, Martin AA, Terrin N, Marsh JV, et al. Comorbidity and other factors associated with modality selection in incident dialysis patients: the CHOICE Study. Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39(2):324–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chanouzas D, Ng KP, Fallouh B, Baharani J. What influences patient choice of treatment modality at the pre-dialysis stage? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27(4):1542–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harwood L, Clark AM. Understanding pre-dialysis modality decision-making: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50(1):109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Just PM, de Charro FT, Tschosik EA, Noe LL, Bhattacharyya SK, Riella MC. Reimbursement and economic factors influencing dialysis modality choice around the world. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23(7):2365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Palmer SC, de BG, Craig JC, Tong A, Tonelli M, Pellegrini F, et al. Patient satisfaction with in-centre haemodialysis care: an international survey. BMJ Open 2014; 4(5):e005020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maaroufi A, Fafin C, Mougel S, Favre G, Seitz-Polski B, Jeribi A, et al. Patients' preference regarding choice of end-stage renal disease treatment options. Am J Nephrol 2013; 37(4):359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goovaerts T, Jadoul M, Goffin E. Influence of a pre-dialysis education programme (PDEP) on the mode of renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20(9):1842–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ribitsch W, Haditsch B, Otto R, Schilcher G, Quehenberger F, Roob JM, et al. Effects of a pre-dialysis patient education program on the relative frequencies of dialysis modalities. Perit Dial Int 2013; 33(4):367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Just PM, Riella MC, Tschosik EA, Noe LL, Bhattacharyya SK, de Charro F. Economic evaluations of dialysis treatment modalities. Health Policy 2008; 86(2-3):163–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blotiere PO, Tuppin P, Weill A, Ricordeau P, Allemand H. The cost of dialysis and kidney transplantation in France in 2007, impact of an increase of peritoneal dialysis and transplantation. Nephrol Ther 2010; 6(4):240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. U S Renal Data System USRDS 2012 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States; 2012.

- 32. Cleemput I, Beguin Cl, De la Kethulle Y, Gerkens S, Jadoul M, Verpooten G, et al. Organisation et financement de la dialyse chronique en Belgique. KCE reports 124B. Bruxelles: Centre fédéral d'expertise des soins de santé; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. McFarlane PA. Reducing hemodialysis costs: conventional and quotidian home hemodialysis in Canada. Semin Dial 2004; 17(2):118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mowatt G, Vale L, Perez J, Wyness L, Fraser C, Macleod A, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and economic evaluation, of home versus hospital or satellite unit haemodialysis for people with end-stage renal failure. Health Technol Assess 2003; 7(2):1–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winkelmayer WC, Weinstein MC, Mittleman MA, Glynn RJ, Pliskin JS. Health economic evaluations: the special case of end-stage renal disease treatment. Med Decis Making 2002; 22(5):417–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Couchoud C, Dantony E, Elsensohn MH, Villar E, Ecochard R, REIN Registry Modelling treatment trajectories to optimize the organization of renal replacement therapy and public health decision-making. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28(9):2372–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Couchoud C, Couillerot AL, Dantony E, Elsensohn MH, Labeeuw M, Villar E, et al. Economic impact of a modification of the treatment trajectories of patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015. [epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Plantinga LC, Fink NE, Finkelstein FO, Powe NR, Jaar BG. Association of peritoneal dialysis clinic size with clinical outcomes. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29(3):285–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.