Abstract

Background

Proper management of small bowel obstruction (SBO) requires a methodology to prevent nontherapeutic laparotomy while minimizing the chance of overlooking strangulation obstruction causing intestinal ischemia. Our aim was to identify preoperative risk factors associated with strangulating SBO and to develop a model to predict the need for operative intervention in the presence of an SBO. Our hypothesis was that free intraperitoneal fluid on computed tomography (CT) is associated with the presence of bowel ischemia and need for exploration.

Methods

We reviewed 100 consecutive patients with SBO, all of whom had undergone CT that was reviewed by a radiologist blinded to outcome. The need for operative management was confirmed retrospectively by four surgeons based on operative findings and the patient’s clinical course.

Results

Patients were divided into two groups: group 1, who required operative management on retrospective review, and group 2 who did not. Four patients who were treated nonoperatively had ischemia or died of malignant SBO and were then included in group 1; two patients who had a nontherapeutic exploration were included in group 2. On univariate analysis, the need for exploration (n = 48) was associated (p < 0.05) with a history of malignancy (29% vs. 12%), vomiting (85% vs. 63%), and CT findings of either free intraperitoneal fluid (67% vs. 31%), mesenteric edema (67% vs. 37%), mesenteric vascular engorgement (85% vs. 67%), small bowel wall thickening (44% vs. 25%) or absence of the “small bowel feces sign” (so-called fecalization) (10% vs. 29%). Ischemia (n = 11) was associated (p < 0.05 each) with peritonitis (36% vs. 1%), free intraperitoneal fluid (82% vs. 44%), serum lactate concentration (2.7 ± 1.6 vs. 1.3 ± 0.6 mmol/l), mesenteric edema (91% vs. 46%), closed loop obstruction (27% vs. 2%), pneumatosis intestinalis (18% vs. 0%), and portal venous gas (18% vs. 0%). On multivariate analysis, free intraperitoneal fluid [odds ratio (OR) 3.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.5–9.9], mesenteric edema (OR 3.59, 95% CI 1.3–9.6), lack of the “small bowel feces sign” (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.05–0.68), and a history of vomiting (OR 4.67, 95% CI 1.5–14.4) were independent predictors of the need for operative exploration (p < 0.05 each). The combination of vomiting, no “small bowel feces sign,” free intraperitoneal fluid, and mesenteric edema had a sensitivity of 96%, and a positive predictive value of 90% (OR 16.4, 95% CI 3.6–75.4) for requiring exploration.

Conclusion

Clinical, laboratory, and radiographic factors should all be considered when making a decision about treatment of SBO. The four clinical features—intraperitoneal free fluid, mesenteric edema, lack of the “small bowel feces sign,” history of vomiting—are predictive of requiring operative intervention during the patient’s hospital stay and should be factored strongly into the decision-making algorithm for operative versus nonoperative treatment.

Introduction

Appropriate management of acute small bowel obstruction (SBO) has been and continues to be a common clinical challenge [1, 2]. The goal of treatment is to recognize both promptly and precisely the presence of intestinal ischemia to establish an appropriate clinical plan. The traditional surgical dictum in patients with a complete SBO has been to operate within 12–24 h in proper scenarios—that is, “The sun should never rise and set on a complete SBO.” Traditional management, however, can lead to nontherapeutic laparotomy along with the associated morbidities and further adhesion and its potential sequelae [3, 4]. Therefore, nonoperative management, using nasogastric decompression and fluid resuscitation with close and frequent clinical reassessment, has proven to be successful in a substantial percentage of selected patients with SBO. Unfortunately, a nonselective, nonoperative plan can be dangerous [5, 6]. When embarking on an initial nonoperative approach, surgeons must be flexible to manage those patients properly with persistence or progression of their symptoms because late recognition of a strangulation obstruction is associated with markedly increased morbidity and mortality [7, 8].

Clinical parameters included in the history and physical examination, laboratory analysis, and imaging modalities can be used as clues to provide a better assessment of the risk of underlying strangulation and an appropriate plan of treatment [4, 8, 9]. Our hypothesis was that the presence of a recognizable amount of free intraperitoneal fluid on abdominal/pelvic computed tomography (CT) is associated with the need for exploration and with the presence of underlying intestinal ischemia. Therefore, our aim was to identify retrospectively selected clinical factors, such as free peritoneal fluid, using both univariate and multivariate analyses to predict successfully which patients will at some point require operative intervention during their hospitalization for either strangulation obstruction or nonresolving SBO.

Materials and methods

Institutional review board authorization was obtained to review retrospectively 100 consecutive adult patients from January through May 2006 with signs and symptoms consistent with SBO who had undergone concurrent CT. Patients with a known history of ascites, laparotomy, or laparoscopy within 6 weeks were excluded. All CT scans were available for review by an experienced staff radiologist (P.W.E.) who was blinded to the clinical course. The appropriateness of the operative or nonoperative approach to management was determined by consensus of the four contributing surgeons (M.D.Z., M.P.B., S.F.H., M.G.S.) based on findings at exploration (either laparotomy or laparoscopy) and the ultimate clinical course of each patient. Patients with an SBO and no prior abdominal operation underwent exploration.

Recorded features of the patients’ histories included age, sex, and the presence of obstipation or vomiting, number and type of prior abdominal procedures, history of prior SBO, hernia, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular co-morbidities, abdominal irradiation, Crohn’s disease, and malignancy. Chart review for duration of obstipation data was inconsistent, and therefore this feature was not included in the analysis. Features of interest on the physical examination included fever, tachycardia, abdominal distension, and peritonitis. The laboratory factors evaluated included serum lactate concentration (mmol/l) and white blood cell count (× 109/l).

CT: methodology and interpretation

A total of 92 of 100 CT examinations were performed at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Contiguous images of ≤5 mm thickness were obtained through the abdomen and pelvis using a variety of multidetector row CT scanners (Siemens Sensation 64, Sensation Open, and Sensation 16: Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA, USA; and GE LightSpeed Pro 16, LightSpeed 16, and LightSpeed Ultra: GE Medical Systems, Carrollton, TX, USA). Intravenous contrast material was administered to 66 of 92 patients; a standard dose of 140 ml of iohexol (Omnipaque 300; Amersham Health, Princeton, NJ, USA) with an iodine concentration of 300 mg/ml was used. The volume was decreased in patients with compromised renal function (serum creatinine > 1.4 g/dl) according to a standard protocol. Gastrografin contrast was administered to 30 of 92 patients. Eight CT examinations were performed at outside institutions using a variety of CT scanners and scan techniques; all were deemed to be of acceptable quality.

The specific findings on CT that we postulated might be important clinical determinants of outcome were evaluated. Features of interest in the small intestine included the presence of dilation, air-fluid levels, “small bowel feces sign” (gas bubbles and debris within the obstructed small bowel lumen, often referred to as “fecalization”), thickened wall, pneumatosis intestinalis, a definite transition point (decompressed small bowel distal to dilated small bowel), and findings suggestive of a closed loop obstruction (single, isolated segment of dilated small intestine) [10, 11]. Features of interest in the small bowel mesentery included edema, defined by hazy fluid attenuation in the mesentery of the involved intestinal segment and vascular engorgement or vascular “swirling.” Other findings of interest on CT included the presence of free intraperitoneal fluid, portal venous gas, and free intraperitoneal air.

Analysis of data

There were 52 women and 48 men with an average age of 64 years (range 18–96 years). Patients were grouped according to whether they needed operative treatment (group 1, with 48 patients) or whether they could have initially been managed nonoperatively (group 2, with 52 patients). Four patients who were treated nonoperatively but who had small bowel ischemia or died in hospice of nonresolving malignant SBO were included in group 1 because they died of complications of SBO. Two patients underwent operative exploration and were included subsequently in group 2 (Table 1), one who underwent non-therapeutic laparotomy and another who underwent feeding jejunostomy revision unrelated to obstruction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients placed in the opposite group

| Patient no. | Group | SBO procedure | SBO etiology | Morbidity | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | None | Malignancy | None | Yes |

| 2 | 1 | None | Malignancy | None | Yes |

| 3 | 1 | None | Malignancy | None | Yes |

| 4 | 1 | None | Adhesions | Stroke | Yes |

| 5 | 2 | Nontherapeutic | None | Hernia | No |

| 6 | 2 | J-Tube revision | None | Dehiscence | No |

SBO small bowel obstruction

Associations of morbidity, hospital mortality, time from admission to exploration, and duration of hospital stay were compared between groups using the chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The magnitude of the association of each feature studied with both small bowel ischemia and the need for operative management was evaluated using univariate logistic regression models and summarized with an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The features that were significantly associated with the need for operative management in a multivariable setting were determined using stepwise logistic regression models with a 0.05 significance level and a model-free classification procedure called random forests. This approach ranks each feature by its ability to discriminate between patients who did and did not need operative treatment while controlling for interactions among features. The predictive ability of this multivariable model was evaluated using a c index, which in the setting of a logistic regression model is equivalent to the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The c index ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, with values of 0.5 indicating no predictive ability and 1.0 indicating perfect predictive ability. All tests were two-sided with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

The etiology and management of SBO are summarized in Table 2. The most common etiology in group 1 was an obstructing neoplasm, with adhesive disease as the second most common cause. Adhesive disease was the most common (presumed) etiology in group 2. About half of the patients in group 1 underwent bowel resection with primary anastomosis. Lysis of adhesions, herniorrhaphy, palliative intestinal bypass, and stoma formation accounted for the remaining portion of the group.

Table 2.

Etiology and treatment of patients with SBO

| Parameter | Group 1 (n = 48) | Group 2 (n = 52) |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | ||

| Adhesive disease | 13 (27%) | 33 (63%) |

| Cancer/tumor | 17 (35%) | 5 (10%) |

| Unknown | 0 | 5 (10%) |

| Hernia | 6 (13%) | 3 (6%) |

| Constipation | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Stricture/stenosis | 0 | 3 (6%) |

| Radiation enteropathy | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Internal hernia | 5 (10%) | 0 |

| Volvulus | 3 (6%) | 0 |

| Intussusception | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Phlegmon/abscess | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Meckel’s band | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Procedure | ||

| Nontherapeutic exploration | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| Bowel resection, anastomosis | 23 (52%) | 1 (50%) |

| Lysis of adhesions only | 10 (23%) | 0 |

| Hernia repair | 6 (14%) | 0 |

| Intestinal bypass/diversion | 2 (5%) | 0 |

| Bowel resection, stoma(s) | 3 (7%) | 0 |

Group 1 had greater morbidity (52% vs. 21%, p = 0.001) and in-house mortality (19% vs. 0%, p < 0.001) rates than group 2. The presence of strangulation obstruction conferred greater morbidity (82% vs. 30%, p = 0.002), but the difference in hospital mortality was not statistically significant (18% vs. 8%, p = 0.257), albeit the numbers were small. The average time from admission to laparotomy was 1.5 days (median 0 days, range 0–6 days) when strangulation obstruction was present; the time to operative treatment increased to 5.3 days (median 2.5 days, range 0–38 days) in patients without strangulation obstruction (p = 0.042). Group 1 had a longer hospital stay (median 13 vs. 5 days, p < 0.001), and the presence of a strangulation obstruction increased the time until hospital dismissal (median 13 vs. 7 days, p = 0.045)

Univariate analysis

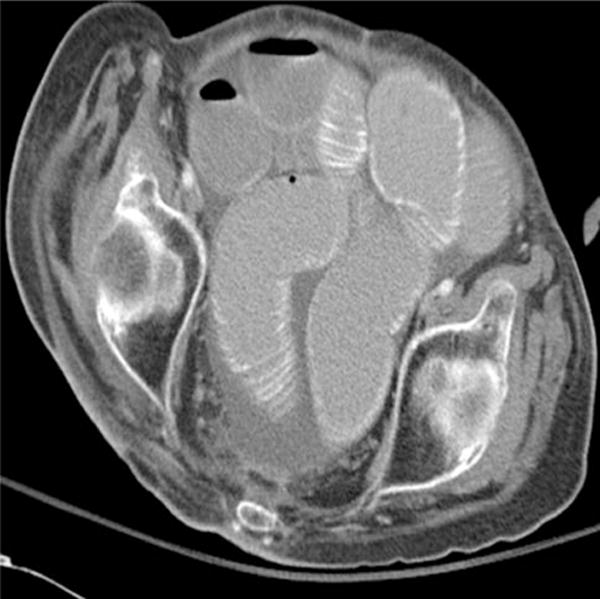

Univariate associations of the clinical and CT findings with the need for operative treatment are summarized in Table 3. On univariate analysis, the need for operative treatment was significantly associated with malignancy, vomiting, and CT findings of free intraperitoneal fluid (Fig. 1), mesenteric edema (Fig. 2), mesenteric vascular engorgement, and thickened small intestinal wall. In contrast, the features associated with successful nonoperative management included a history of prior abdominal operations, prior hospitalization for SBO, and the “small bowel feces sign.”

Table 3.

Univariate associations with the need for operative exploration

| Group 1 (n = 48) |

Group 2 (n = 52) |

OR (95% CI) | p | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History/physical examination | ||||||||

| Male sex | 20 (42%) | 28 (54%) | 0.61 (0.28–1.35) | 0.224 | 42 | 46 | 42 | 46 |

| Age (median years) | 65 | 67 | 1.00 (0.97–1.02)a | 0.828 | ||||

| Prior abdominal procedures (median) | 2 | 2 | 0.88 (0.71–1.08)a | 0.224 | ||||

| Disease history | ||||||||

| SBO | 13 (27%) | 25 (48%) | 0.40 (0.17–0.93) | 0.033 | 27 | 52 | 34 | 44 |

| Prior abdominal procedures | 38 (79%) | 50 (96%) | 0.15 (0.03–0.74) | 0.019 | 79 | 4 | 43 | 17 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (17%) | 10 (19%) | 0.84 (0.30–2.34) | 0.739 | 17 | 81 | 44 | 51 |

| Cardiac disease | 13 (27%) | 18 (35%) | 0.70 (0.30–1.65) | 0.417 | 27 | 65 | 42 | 49 |

| Vascular disease | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0.63 (0.14–2.78) | 0.583 | 6 | 90 | 38 | 51 |

| Abdominal irradiation | 6 (13%) | 3 (6%) | 2.33 (0.55–9.91) | 0.251 | 13 | 94 | 67 | 54 |

| Crohn’s disease | 0 | 4 (8%) | NA** | 0.119 | 0 | 92 | 0 | 50 |

| Malignancy | 14 (29%) | 6 (12%) | 3.16 (1.10–9.06) | 0.033 | 29 | 88 | 70 | 58 |

| Abdominal distension | 36 (75%) | 31 (60%) | 2.03 (0.86–4.79) | 0.105 | 75 | 40 | 54 | 64 |

| Peritonitis | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 4.64 (0.50–43.03) | 0.177 | 8 | 98 | 80 | 54 |

| Vomiting | 41 (85%) | 33 (63%) | 3.37 (1.27–8.99) | 0.015 | 85 | 37 | 55 | 73 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||||||

| Temperature ≥ 38.5°C | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 3.40 (0.34–33.86) | 0.297 | 6 | 98 | 75 | 53 |

| Heart rate ≥ 100 | 13 (27%) | 8 (15%) | 2.04 (0.76–5.48) | 0.156 | 27 | 85 | 62 | 56 |

| Leukocytosis (>10.5 × 109/l) | 19 (40%) | 17 (33%) | 1.31 (0.58–2.98) | 0.519 | 40 | 67 | 53 | 54 |

| Serum lactate (mmol/l) | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.46 (0.86–2.49)* | 0.161 | ||||

| CT parameters | ||||||||

| Small bowel dilatation | 43 (90%) | 44 (85%) | 1.56 (0.47–5.16) | 0.463 | 90 | 15 | 49 | 62 |

| Small bowel feces sign | 5 (10%) | 15 (29%) | 0.29 (0.10–0.87) | 0.027 | 10 | 71 | 25 | 46 |

| Mesenteric edema | 32 (67%) | 19 (37%) | 3.47 (1.52–7.92) | 0.003 | 67 | 63 | 63 | 67 |

| Mesenteric vascular engorgement | 41 (85%) | 35 (67%) | 2.85 (1.06–7.65) | 0.038 | 85 | 33 | 54 | 71 |

| Small bowel wall thickening | 21 (44%) | 13 (25%) | 2.33 (1.00–5.45) | 0.050 | 44 | 75 | 62 | 59 |

| Transition point | 30 (63%) | 33 (63%) | 0.96 (0.43–2.16) | 0.921 | 63 | 37 | 48 | 51 |

| Free intraperitoneal fluid | 32 (67%) | 16 (31%) | 4.50 (1.94–10.43) | <0.001 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 69 |

| Closed loop obstruction | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 4.64 (0.50–43.03) | 0.177 | 8 | 98 | 80 | 54 |

| Small bowel air fluid level | 48 (100%) | 51 (98%) | NA | 1.000 | 100 | 2 | 48 | 100 |

| Pneumatosis intestinalis | 2 (4%) | 0 | NA | 0.228 | 4 | 100 | 100 | 53 |

| Portal venous gas | 2 (4%) | 0 | NA | 0.228 | 4 | 100 | 100 | 53 |

| Extraluminal enteric contrast | 0 | 1 (2%) | NA | 1.000 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 52 |

| Free intraperitoneal air | 1 (2%) | 0 | NA | 0.480 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 53 |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

NA: Odds ratio could not be estimated because either none of the patients with the feature needed an operation (Crohn’s disease), none of the patients lacking the feature needed an operation (small bowel air fluid level), or all of the patients with the feature needed an operation (pneumotosis, PV gas, free air)

Odds ratios represent the increased risk of the need for an operation with each 1-unit increase in the feature

Fig. 1.

Intraperitoneal free fluid

Fig. 2.

Mesenteric edema

There were 11 patients with strangulation obstruction, 1 of whom died in the hospital of unrecognized intestinal necrosis after inappropriate nonoperative management. Significant univariate associations with small bowel ischemia (Table 4) included peritonitis, free intraperitoneal fluid, increased serum lactate concentration, mesenteric edema, closed loop obstruction, pneumatosis intestinalis, and portal venous gas. In contrast, patients with prior abdominal surgery were less likely to have strangulation obstruction compared with patients without prior abdominal surgery. Each increase in the serum lactate concentration of 1 mmol/l was associated with a greater than threefold increased risk of strangulation obstruction, although this feature was measured in only 74 patients, of whom 9 had strangulation obstruction. Only 51% of patients underwent abdominal plain radiograph prior to CT, and therefore these results were not included in the analysis.

Table 4.

Univariate associations with strangulation-obstruction

| Parameter | Ischemic bowel (n = 11) |

Viable bowel (n = 89) |

OR (95% CI) | p | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History/physical examination | ||||||||

| Male sex | 7 (64%) | 41 (46%) | 2.05 (0.56–7.50) | 0.279 | 64 | 54 | 15 | 92 |

| Age (median years) | 66 | 66 | 1.02 (0.98–1.07)a | 0.369 | ||||

| Prior abdominal procedures (median) | 2 | 2 | 0.77 (0.50–1.18)a | 0.228 | ||||

| Disease history | ||||||||

| SBO | 3 (27%) | 35 (39%) | 0.58 (0.14–2.33) | 0.442 | 27 | 61 | 8 | 87 |

| Prior abdominal procedures | 7 (64%) | 81 (91%) | 0.17 (0.04–0.72) | 0.016 | 64 | 9 | 8 | 67 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (27%) | 15 (17%) | 1.85 (0.44–7.80) | 0.402 | 27 | 83 | 17 | 90 |

| Cardiac disease | 6 (55%) | 25 (28%) | 3.07 (0.86–10.98) | 0.084 | 55 | 72 | 19 | 93 |

| Vascular disease | 1 (9%) | 7 (8%) | 1.17 (0.13–10.53) | 0.888 | 9 | 92 | 13 | 89 |

| Abdominal radiation | 1 (9%) | 8 (9%) | 1.01 (0.11–8.96) | 0.991 | 9 | 91 | 11 | 89 |

| Crohn’s disease | 0 | 4 (4%) | NA | 1.000 | 0 | 96 | 0 | 89 |

| Malignancy | 1 (9%) | 19 (21%) | 0.37 (0.04–3.06) | 0.355 | 9 | 79 | 5 | 88 |

| Abdominal distension | 9 (82%) | 58 (65%) | 2.41 (0.49–11.83) | 0.280 | 82 | 35 | 13 | 94 |

| Peritonitis | 4 (36%) | 1 (1%) | 50.29 (4.93–512.99) | < 0.001 | 36 | 99 | 80 | 93 |

| Vomiting | 10 (91%) | 64 (72%) | 3.91 (0.48–32.12) | 0.205 | 91 | 28 | 14 | 96 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||||

| Temperature ≥ 38.5°C | 1 (9%) | 3 (3%) | 2.87 (0.27–30.24) | 0.381 | 9 | 97 | 25 | 90 |

| Heart rate ≥100 | 3 (27%) | 18 (20%) | 1.48 (0.36–6.15) | 0.590 | 27 | 80 | 14 | 90 |

| Leukocytosis (>10.5 × 109/l) | 8 (73%) | 28 (32%) | 5.71 (1.41–23.19) | 0.015 | 73 | 68 | 22 | 95 |

| Serum lactate (mmol/l) | 2.7 ± 1.6 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 3.28 (1.52–7.05)a | 0.002 | ||||

| CT parameter | ||||||||

| Small bowel dilatation | 10 (91%) | 77 (87%) | 1.56 (0.18–13.30) | 0.685 | 91 | 13 | 11 | 92 |

| Small bowel feces sign | 1 (9%) | 19 (21%) | 0.37 (0.04–3.06) | 0.355 | 9 | 79 | 5 | 88 |

| Mesenteric edema | 10 (91%) | 41 (46%) | 11.70 (1.44–95.27) | 0.022 | 91 | 54 | 20 | 98 |

| Mesenteric vascular engorgement | 9 (82%) | 67 (75%) | 1.48 (0.30–7.36) | 0.634 | 82 | 25 | 12 | 92 |

| Small bowel wall thickening | 5 (45%) | 29 (33%) | 1.72 (0.49–6.12) | 0.399 | 45 | 67 | 15 | 91 |

| Transition point | 7 64%) | 56 (63%) | 1.03 (0.28–3.79) | 0.963 | 64 | 37 | 11 | 89 |

| Free intraperitoneal fluid | 9 (82%) | 39 (44%) | 5.77 (1.18–28.24) | 0.031 | 82 | 56 | 19 | 96 |

| Closed loop obstruction | 3 (27%) | 2 (2%) | 16.31 (2.37–112.40) | 0.005 | 27 | 98 | 60 | 92 |

| Small bowel air fluid level | 11 (100%) | 88 (99%) | NA | 1.000 | 100 | 1 | 11 | 100 |

| Pneumatosis intestinalis | 2 (18%) | 0 | NA | 0.011 | 18 | 100 | 100 | 91 |

| Portal venous gas | 2 (18%) | 0 | NA | 0.011 | 18 | 100 | 100 | 91 |

| Extraluminal enteric contrast | 0 | 1 (1%) | NA | 1.000 | 0 | 99 | 0 | 89 |

| Free intraperitoneal air | 1 (9%) | 0 | NA | 0.110 | 9 | 100 | 100 | 90 |

Odds ratios represent the increased risk of small bowel ischemia with each 1-unit increase in the feature

NA: Odds ratio could not be estimated since either none of the patients with the feature had ischemia (Crohn’s disease), none of the patients lacking the feature had ischemia (small bowel air fluid level); or all of the patients with the feature had ischemia (pneumotosis, PV gas, and free air). p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact tests

Multivariate analysis

On multivariate analysis, the clinical findings significantly associated with the need for operative treatment included vomiting, mesenteric edema, free intraperitoneal fluid, and no “small bowel feces sign” (Table 5). The c index from this multivariable model was 0.79. Patients with vomiting were 4.7 times more likely to require eventual operative treatment. The small bowel feces sign was associated with a greater than fivefold decreased risk of the need for an operation. Mesenteric edema and free intraperitoneal fluid were associated with 3.6- and a 3.8-fold increased risk, respectively.

Table 5.

Multivariate associations with the need for operative exploration in SBO

| Feature | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | 4.67 (1.51–14.43) | 0.007 |

| Small bowel feces sign | 0.19 (0.05–0.68) | 0.011 |

| Free intraperitoneal fluid | 3.80 (1.46–9.92) | 0.006 |

| Mesenteric edema | 3.59 (1.34–9.62) | 0.011 |

Altogether, 21 patients had the combination of vomiting, no small bowel feces sign, mesenteric edema, and free intraperitoneal fluid; 19 (90%) of them required operative exploration. This clinical presentation resulted in a sensitivity of 40%, specificity of 96%, and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 90% regarding the need for operative treatment. The patients with this combination of features were more than 16 times more likely to require operative treatment than patients having other combinations of these clinical features. This combination of symptoms and findings is important because of these 21 patients 13 (62%) were treated initially nonoperatively at the time of presentation. The mortality rate related directly to the episode of SBO in these 13 patients was substantially greater when compared to the 8 patients who were treated initially (within the first 12 h) by operative exploration (54% vs. 0%, p = 0.018). These 13 patients, compared to the other 8 patients, had similar morbidity (69% vs. 50%, p = 0.646) and duration of stay (14 vs. 11 days, p = 0.342). When three or more of these predictive factors were present (n = 47), there was a sensitivity of 69%, specificity of 73%, and PPV of 70% for requiring operative exploration. As expected, the predictive value for requiring operative exploration decreased with fewer predictive features. When two or more features were present, the sensitivity was 100%, specificity was 25%, and the PPV was 55% with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 100%. Interestingly, none of the patients with one or fewer predictive features required operative exploration (Table 6). No multivariable modeling was performed for the patients with strangulation obstruction because there were too few patients with small bowel ischemia to support more than one feature in a model (n = 11).

Table 6.

Predicted need for operative intervention based on the number of risk factors present

| Risk factors (no.) | Predicted need for operative intervention (%) | Relative risk for operative intervention | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 90 | 16 | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 70 | 6 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 55 | 0.5 | 0.088 |

| 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| None | 0 | NA | NA |

NA: Risk could not be estimated since there were no patients with less than 2 clinical features that required operative intervention

Discussion

Timely and appropriate operative treatment of SBO should improve morbidity and mortality rates, although accurately determining which patients should undergo operative therapy during the hospitalization can be difficult [5, 7]. No definable learning curve exists because even the most senior surgeons are inaccurate predictors [12]. When the traditional signs of vascular compromise of the bowel (i.e., fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, peritonitis) are present, operative exploration is clearly indicated. When only a few of these features are present, however, the clinical picture and the need for operative intervention may be much less certain. Additionally, CT images contain a multitude of information, but which features on CT predict the need for operative intervention? To address these issues, our aim was to develop a multivariate model that would assist surgeons in predicting which patients with SBO should undergo early exploration in an attempt not only to decrease morbidity and mortality by shortening unsuccessful periods of nonoperative management but also to identify those patients at greatest risk of harboring an underlying strangulation obstruction.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the CT features that correlate with the diagnosis of SBO [13–16]. More recently, authors have attempted to identify risk factors that correlate with strangulation obstruction to predict the need for operative management to prevent delayed recognition of infarcted bowel [9, 17]. Bias is present inherently in these studies, however, because the endpoints are based on operative exploration, which may or may not have been therapeutic or necessary. We maintain that every experienced surgeon can remember patients for whom they wish, in retrospect, that a different plan of care had been undertaken, such as nonoperative management of a strangulation obstruction or perhaps performing a nontherapeutic laparotomy. This is the very reason a predictive model is needed; a surgeon’s judgment is not absolute and can be wrong. Additionally, patient populations such as those with advanced malignant SBO may choose not to undergo operative treatment even if indicated. In the current study, there were six patients who were analyzed in the opposite group after evaluation of their hospital course. After discussion among the surgeon authors, three patients were determined in retrospect to have been treated inappropriately. In addition, there were three patients with SBO secondary to widespread malignancy who met indications for operative management but because of their specific clinical scenario the management team and the patient together decided not to pursue operative treatment. These patients would have been put into what we consider to be the “wrong” group if looked at purely from an operative versus nonoperative standpoint. The correct endpoint for analyzing these patients, therefore, is not whether they had an operation but whether they should or should not have undergone exploration. We maintain that this novel approach strengthens our model.

Consensus exists that a multivariate model would offer the best approach to predict the presence of strangulation obstruction [17]. To this end, several attempts have been made to create a predictive model to help direct appropriate treatment of SBO, but these studies used data from select portions of the entire clinical scenario [9, 18–20]. Instead, our model attempted to identify the relevant features from the entire clinical scenario, including the history, physical examination, laboratory evaluation, and CT imaging.

Multiple randomized, prospective trials have examine the use of water-soluble contrast material—i.e., methylglucamine diatrizoate (Gastrografin) or sodium diatrizoate/meglumine diatrizoate (Urografin)—as a therapeutic intervention in the setting of adhesive SBO [21–28]. The results are mixed as to whether a therapeutic benefit to water-soluble contrast is realized. An implication within these studies, however, is the predictability of the contrast challenge. Whereas some studies suggested that contrast that transits to the colon within a 4- to 72-hour range predicts a lesser chance that operative intervention is required [22–26], the remaining studies showed no evidence of predictability [27–29]. The model we present has several advantages over a water-soluble contrast challenge. Our model predicts the need for exploration at admission and can therefore avoid unnecessary delays of nonoperative management and its associated fluid, electrolyte, and nutrition complications. Additionally, early recognition of those patients who will require operative intervention can avoid nonoperative management of a strangulation obstruction. Lastly, contrast aspiration is a rare but real risk associated with contrast administration in the setting of SBO. This complication is avoided in our model. A head-to-head comparison of these methods may be worth pursuing.

“Complete” bowel obstruction is defined by dilated loops of small bowel without gas in the colon on abdominal plain radiography, whereas with “partial” obstruction gas is demonstrated in the colon [29]. Only half of the cohort underwent abdominal plain radiography preoperatively, leading us to exclude this factor from analysis. As a surrogate for complete (versus partial) obstruction, we looked for the presence of a transition point on CT. There was no association on univariate or multivariate analysis with this sign. Owing to the low sensitivity and specificity of plain abdominal radiography [16], we believe it is a useful first examination if the question of SBO is uncertain but that it consumes too much time and money if a strong pretest probability exists. Most of these patients undergo subsequent CT imaging. If, however, plain abdominal radiography confirms a diagnosis of SBO and operative exploration is planned based on the results combined with the history and physical examination, CT need not be performed.

After multivariate analysis, we found four clinical signs (vomiting, lack of the small bowel feces sign, mesenteric edema, free intraperitoneal fluid) that offered independent predictive value for the need for operative treatment in these 100 patients with SBO. One of our primary interests was whether the presence of any amount of free intra-peritoneal fluid on CT was associated with both the need for operative treatment and the presence of strangulation obstruction. Several studies have demonstrated a correlation of free intraperitoneal fluid with the need for operative intervention and small bowel ischemia, corroborating our findings and correlating with our clinical experience. A recent report was able to show a threefold increase in the need for operative intervention if free intraperitoneal fluid was present on CT [19]. Additionally, “large” amounts of free intraperitoneal fluid (i.e., overflow from the pelvic cavity) has been shown to be associated with strangulation obstruction [20]. A multivariate analysis correlated this finding and also demonstrated that CT is able to differentiate strangulated from nonstrangulated obstructions [30]. Conversely, other studies examining this same finding were unable to find an association of free intraperitoneal fluid and strangulation obstruction [9, 13, 31]. We excluded patients with a known history of ascites or a recent abdominal exploration to eliminate confusion on this feature. Therefore, our model does not apply to these patient populations. Despite the conflicting data in the literature, we believe the presence of free intraperitoneal fluid on CT is predictive of requiring operative intervention and is include in our predictive model. Mesenteric edema on CT also appears to be a marker of potential compromise of the adjacent bowel wall, predictive for the need of operative treatment. The small bowel feces sign has been shown previously to be associated with strangulation obstruction [9]. We were unable to corroborate this finding; and indeed to our initial surprise, we found that the small bowel feces sign in the setting of SBO was actually predictive of the lack of need for operative intervention. Absorptive function of the small bowel in the presence of a complete obstruction is deranged markedly [16]. We hypothesize that the small bowel feces sign is evident when the small bowel is able to resorb fluid, resulting an air–debris mixture; this finding may imply a less severe obstruction owing to functioning small bowel. Further study is needed to verify our result. The presence of vomiting is a common sign in patients with SBO. Vomiting suggests a more proximal or long-standing distal obstruction and potential seriousness and duration than if it is absent. The commonality of this sign between the two groups (i.e., specificity), however, decreases its clinical usefulness when evaluated alone; in combination with the other features, however, it has strong predictive ability.

Patients who were managed nonoperatively during their initial consultation, despite having the four multivariate features identified, had poorer outcomes. In our data set, more than half of these patients were treated “conservatively” at their initial evaluation. Our findings suggest that a more “conservative” approach to the management of these patients may actually be to proceed directly to the operating room because this treatment reduces morbidity and mortality by avoiding delay in treatment of an underlying strangulation obstruction in 62% of these patients. This approach may prevent several unnecessary days of nasogastric decompression and its corresponding fluid, electrolyte, and nutrition derangements in addition to decreasing the duration of stay and the corresponding potential for developing infection or colonization from nosocomial bacteria. Most importantly, this approach minimizes the potential for inappropriately managing a strangulation obstruction inadvertently by a nonoperative approach.

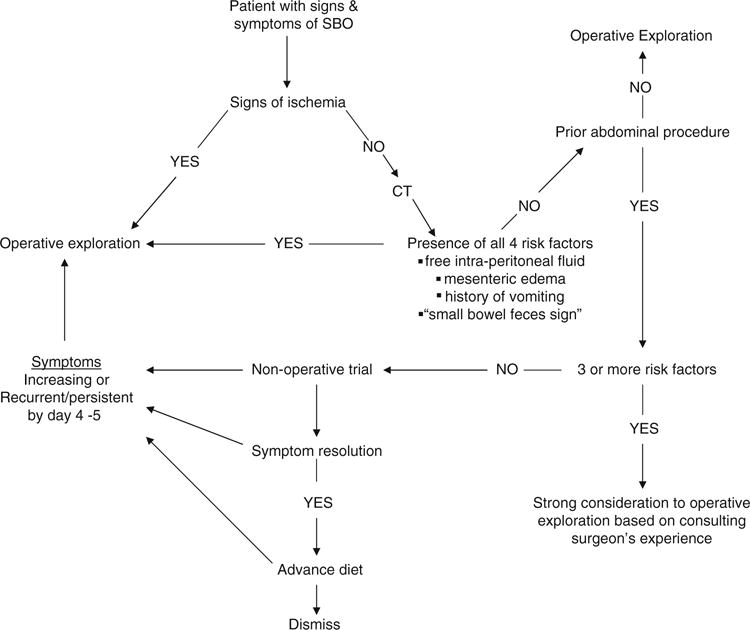

We developed an algorithm (Fig. 3). If a patient with SBO has signs of small bowel ischemia, peritonitis, hypotension, lactic acidosis, and radiologic features of closed loop obstruction, pneumatosis intestinalis, and portal venous gas, immediate operative intervention is indicated. If not, the patient should undergo CT analysis. If all four clinical features are present at this point, continued nonoperative approach is prohibitive and an immediate operative intervention is indicated. Our practice has been to explore patients who have SBO and have never had an abdominal procedure. We undertake CT imaging in this scenario to determine the cause of SBO, as malignancy is more common in this group. When three or more features are present, there is 70% predicted need for operative intervention. We recommend operative intervention for most of these patients. There are, however, clinical scenarios (e.g., malignant obstruction, known dense adhesions) that confer a higher morbidity with operative intervention. These select patients may undergo initial nonoperative management with constant reevaluation. There is a significant chance that nonoperative management could be successful when fewer than two features are present. Therefore, we recommend a strong consideration of initial nonoperative management. Of course, there must be flexibility in the initial plan based on the evolving clinical course.

Fig. 3.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) treatment algorithm. CT, computed tomography

Our algorithm not only predicts those who need an operation but, just as importantly, those who do not. A recent article by Rocha et al. [32] studied retrospectively 145 cases of high-grade SBO detected on CT. Despite the “high grade” nature of the SBO, 46% of these patients were able to be treated nonoperatively. Although specific CT findings, such as intraperitoneal free fluid and mesenteric edema, were not addressed, this study corroborates our finding that a transition point with distal decompression alone is not an indication for operative intervention: The entire clinical picture must to be taken into account.

Conclusions

Our algorithm is a strong predictive model and can be used in everyday clinical practice. Identification of the four clinical features and appropriate reaction based on the algorithm should decrease mortality with the potential of decreasing the number of hospital days and the morbidity in patients presenting with SBO. We believe that future study in another population will confirm these results.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the International Surgical Week, Adelaide, Australia, September 2009.

Contributor Information

Martin D. Zielinski, Email: zielinski.martin@mayo.edu, Division of Trauma, Critical Care, and General Surgery, Mary Brigh 2-810, St. Mary’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic, 1216 Second Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, USA.

Patrick W. Eiken, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55902, USA

Michael P. Bannon, Division of Trauma, Critical Care, and General Surgery, Mary Brigh 2-810, St. Mary’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic, 1216 Second Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, USA

Stephanie F. Heller, Division of Trauma, Critical Care, and General Surgery, Mary Brigh 2-810, St. Mary’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic, 1216 Second Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, USA

Christine M. Lohse, Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55902, USA

Marianne Huebner, Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55902, USA.

Michael G. Sarr, Division of Trauma, Critical Care, and General Surgery, Mary Brigh 2-810, St. Mary’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic, 1216 Second Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, USA

References

- 1.Mucha P. Small intestinal obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 1987;67:597–620. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bizer LS, Liebling RW, Delany HM, et al. Small bowel obstruction. Surgery. 1981;89:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silen W, Hein MF, Goldman L. Strangulation obstruction of the small intestine. Arch Surg. 1962;85:137–145. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1962.01310010125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laws HL, Aldrete JS. Small bowel obstruction: a review of 465 cases. South Med J. 1976;69:733–734. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197606000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bickell NA, Federman AD, Aufses AH. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fevang BT, Jensen D, Svanes K, et al. Early operation or conservative management of patients with small bowel obstruction? Eur J Surg. 2002;168:475–481. doi: 10.1080/110241502321116488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrock TR. Small intestine. In: Way LW, editor. Current surgical diagnosis and treatment. Appleton & Lange; Norwalk, CT: 1988. pp. 561–585. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett WO, Petro AB, Williamson JW. A current appraisal of problems with gangrenous bowel. Ann Surg. 1976;183:653–659. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197606000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheedy SP, Earnest F, IV, Fletcher JG, et al. CT of small-bowel ischemia associated with obstruction in emergency department patients: diagnostic performance evaluation. Radiology. 2006;241:729–736. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2413050965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalano O. The faeces sign: a CT finding in small-bowel obstruction. Radiologe. 1997;37:417–419. doi: 10.1007/s001170050231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayo-Smith WW, Wittenberg J, Bennett GL, et al. The CT small bowel faeces sign: description and clinical significance. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:765–767. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)83216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarr MG, Bulkley GB, Zuidema GD. Preoperative recognition of intestinal strangulation. Am J Surg. 1983;145:176–182. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balthazar EJ, Birnbaum BA, Megibow AJ, et al. Closed-loop and strangulating intestinal obstruction: CT signs. Radiology. 1992;185:769–775. doi: 10.1148/radiology.185.3.1438761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maglinte DD, Gage SN, Harmon BH, et al. Obstruction of the small intestine: accuracy and role of CT in diagnosis. Radiology. 1993;188:61–64. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.1.8511318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frager D, Medwid SW, Baer JW, et al. CT of small-bowel obstruction: value in establishing the diagnosis and determining the degree and cause. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:37–41. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.1.8273686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maglinte DDT, Howard TJ, Lillemoe KD, et al. Small-bowel obstruction: state-of-the-art imaging and its role in clinical management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou CK, Mak CW, Tzeng WS, et al. CT of small bowel ischemia. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:18–22. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argov S, Itzkovitz D, Wiener F. A new method for differentiating simple intra-abdominal from strangulated small-intestinal obstruction. Curr Surg. 1989;46:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Daly BJ, Ridgway PF, Keenan N, et al. Detected peritoneal fluid in small bowel obstruction is associated with the need for surgical intervention. Can J Surg. 2009;52:201–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha HK, Kim JS, Lee MS, et al. Differentiation of simple and strangulated small-bowel obstructions: usefulness of known CT criteria. Radiology. 1997;204:507–512. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assalia A, Schein M, Kopelman D, et al. Therapeutic effect of oral Gastrografin in adhesive, partial small-bowel obstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 1994;115:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biondo S, Pares D, Mora L, et al. Randomized clinical study of Gastrografin® administration in patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2003;90:542–546. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Gao Y, Ma Q, et al. Randomised clinical trial investigating the effects of combined administration of octreotide and methylglucamine diatrizoate in the older persons with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen SC, Chang KJ, Lee PH, et al. Oral urograffin in postoperative small bowel obstruction. World J Surg. 1999;23:1051–1054. doi: 10.1007/s002689900622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen SC, Lin FY, Lee PH, et al. Water-soluble contrast study predicts the need for early surgery in adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1692–1694. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feigin E, Seror D, Szold A, et al. Water-soluble contrast material has no therapeutic effect on postoperative small bowel obstruction: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Surg. 1996;171:227–229. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar P, Kaman L, Singh G, et al. Therapeutic role of oral water soluble iodinated contrast agent in postoperative small bowel obstruction. Singap Med J. 2009;50:360–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fevang BT, Jensen D, Fevang J, et al. Upper gastrointestinal contrast study in the management of small bowel obstruction: a prospective randomised study. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:39–43. doi: 10.1080/110241500750009681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maglinte DDT, Balthazar EJ, Kelvin FM, et al. The role of radiology in the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1171–1180. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.5.9129407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makita O, Ikushima I, Matsumoto N, et al. CT differentiation between necrotic and nonnecrotic small bowel in closed loop and strangulating obstruction. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:120–124. doi: 10.1007/s002619900458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones K, Mangram AJ, Lebron RA, et al. Can a computed tomography scoring system predict the need for surgery in small-bowel obstruction? Am J Surg. 2007;194:780–784. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha FG, Theman TA, Matros E, et al. Nonoperative management of patients with a diagnosis of high-grade small bowel obstruction by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]