Abstract

Herein we describe promising results from the combination of fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) and diffusion reflection (DR) medical imaging techniques. Three different geometries of gold nanoparticles (GNPs) were prepared: spheres of 20nm diameter, rods (GNRs) of aspect ratio (AR) 2.5, and GNRs of AR 3.3. Each GNP geometry was then conjugated using PEG linkers estimated to be 10nm in length to each of 3 different fluorescent dyes: Fluorescein, Rhodamine B, and Sulforhodamine B. DR provided deep-volume measurements (up to 1cm) from within solid, tissue-imitating phantoms, indicating GNR presence corresponding to the light used by recording light scattered from the GNPs with increasing distance to a photodetector. FLIM imaged solutions as well as phantom surfaces, recording both the fluorescence lifetimes as well as the fluorescence intensities. Fluorescence quenching was observed for Fluorescein, while metal-enhanced fluorescence (MEF) was observed in Rhodamine B and Sulforhodamine B – the dyes with an absorption peak at a slightly longer wavelength than the GNP plasmon resonance peak. Our system is highly sensitive due to the increased intensity provided by MEF, and also because of the inherent sensitivity of both FLIM and DR. Together, these two modalities and MEF can provide a lot of meaningful information for molecular and functional imaging of biological samples.

Keywords: Gold nanoparticles, biomolecular imaging, noninvasive detection, diffusion reflection, fluorescence lifetime imaging, metal enhanced fluorescence, gold nanorods, tissue-imitating phantoms

1. INTRODUCTION

Medical imaging today falls into two main categories: structural and functional imaging. Structural imaging, as the name implies, provides information regarding the spatial structure of the imaged sample. However, it is not necessarily able to differentiate between structures of similar composition, and cannot reveal functional activity of the imaged structures. Meanwhile, functional imaging is able to image biological functions as they occur, and so can reveal information that is hidden in the structure alone. Functional imaging is limited in its difficulty at inferring structural information and also in possible confusion between various areas that function in similar manners. In our talk, we describe the initial developments of a system that, when fully optimized, will be able to provide a very sensitive combination of structural and functional imaging. We developed a single, simple, biocompatible probe usable by two imaging modalities meant to provide these two aspects of medical imaging, and we show initial results from measurements of solid tissue-imitating phantoms. The results have been recently published1.

Our probes of choice are based on gold nanoparticles (GNPs), which are known for their biocompatibility2,3 and significant optical properties4,5. Although particles of spherical symmetry are used more extensively in literature, gold nanorods (GNRs) present additional interesting properties, namely 2 different resonance modes and an easily controllable surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak that can be tuned to the more biologically transparent infra-red (IR) range6. Both gold nanospheres and GNRs were considered for this work.

The two imaging modalities we utilized were fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) and diffusion reflection (DR). FLIM is able to image changes in biological properties and biological functions based on both the traditionally considered fluorescence intensity (FI) as well as the less explored fluorescence lifetime (FLT). While the FI can change with fluorophore concentrations in a sample, the FLT is inherent to particular compounds in particular environments, meaning that it can provide meaningful functional information.7,8 Meanwhile, DR is able to detect particular probes within samples to extract information from within sample volumes (up to 1cm) – thus providing a type of structural information. DR reveals GNR presence corresponding to the light used and GNR SPR by recording light scattered from the GNPs with increasing distance to a photodetector.9–14 Both modalities use non-ionizing light sources, are non-invasive, and have the potential for incredible sensitivity.

We designed our probes for increased fluorescence signals using metal enhanced fluorescence (MEF). Through plasmon effects, metal particles of sub-wavelength size are able to strongly affect the electric field in their vicinity. Thus, fluorophores with absorption matching the GNP SPR and within a certain distance can experience enhanced excitation and decay rates, increasing quantum yield (QY) while improving photostability. Factors that can affect MEF include particle size, fluorophore chosen, and the separation distance between the two to overcome quenching effects while maintaining particle field effects.15 By choosing viable combinations of these parameters, we are able to create highly efficient imaging probes.

Our lab has previously shown combined FLIM and DR usage in phantoms, but in conditions where fluorescence was quenched by the GNPs.16 In the current talk, we describe probes we designed that fluoresce brighter than the background, and we present our ability to detect these probes using the highly sensitive systems of FLIM and DR.1

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

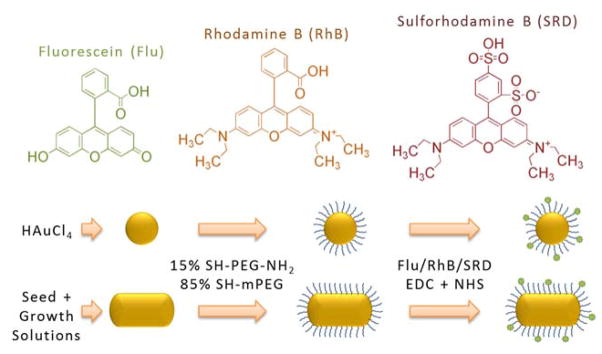

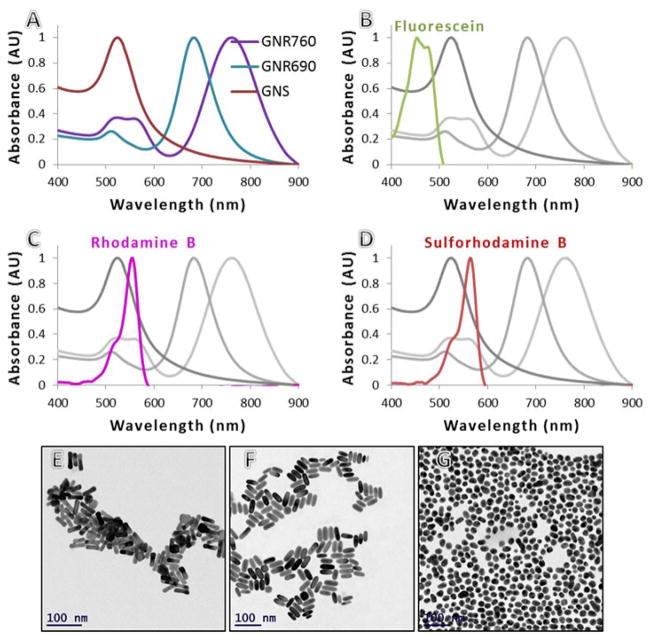

The probes we constructed consisted of GNPs conjugated to fluorescent molecules, and were meant to meet the conditions for MEF. More complete details on the preparation and measurement process can be found in our published work.1 We prepared 3 different geometries of GNPs: spheres of 20nm diameter (GNS), GNRs of aspect ratio (AR) 2.5 (GNR690), and GNRs of AR 3.3 (GNR760). Each GNP type was conjugated using 1kDa PEG linkers, estimated to be 10nm in length on average, to each of 3 fluorophores: Fluorescein (Flu), Rhodamine B (RhB), and Sulforhodamine B (SRB) (see Figure 1). The absorption peaks of Flu, RhB, and SRB are around 470nm, 554nm, and 564nm, respectively, and their QYs are 0.9, 0.3, and 0.8, respectively. Absorption spectra are shown and compared to those of the GNPs in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Scheme depicting the manufacturing process to creating the imaging probe, for both gold nanospheres (GNSs) and gold nanorods (GNRs). Also shown are the chemical structures of the 3 fluorophores used.

Figure 2.

Normalized absorption spectra are shown for the range 400–900 nm, for (A) the 3 GNP geometries, (B) Fluorescein compared to the GNPs, (C) Rhodamine B compared to the GNPs, and (D) Sulforhodamine B compared to the GNPs. TEM images of (E) GNRs with peak at 760nm, (F) GNRs with peak at 690nm, and (G) GNSs.

Using FLIM, we measured the FLT and FI for each combination of GNP and fluorophore, both in solution as well as within solid phantoms. For the FI measurements, the probe solutions were also compared to solutions of the fluorophores alone, not conjugated to GNPs. Solid phantoms were created using Intralipid for scattering, India ink for absorption, and distilled water and/or probe solutions. Agarose was added to solidify the phantoms. Smaller phantoms (~5mm diameter), containing the probe solutions, were placed within larger phantoms (~15mm diameter) of a water or pure fluorophore base to provide contrast. Flu samples were measured using a 473nm laser as an excitation source, while RhB and SRB samples used a 510nm laser excitation source. All FLIM analyses were performed using PQ Symphotime software. The solid phantoms were also measured using the DR system. The DR system consisted of 2 laser diodes of wavelength 650nm and 780nm for excitation sources, and measured scattered light intensities in step sizes of 250μm up to a final light source-detector separation distance of 6mm.

3. RESULTS

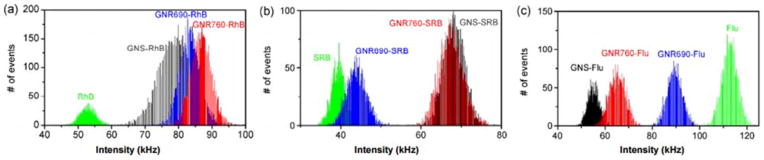

FI results for particle and fluorophore solutions are shown in Figure 3. Solutions were diluted to reach a fluorophore concentration of 1μM, and compared to free fluorophores of the same concentration. In all 3 GNP geometries, fluorescence quenching was observed for Flu, while MEF was observed in RhB and SRB – the dyes with an absorption peak at a slightly longer wavelength than the GNPs’ plasmon resonance peak.

Figure 3.

FI enhancement and quenching due to GNP conjugation in solution. FI is depicted in photon counts per millisecond, or kilohertz. (a) Count rate histograms of GNS, GNR690, and GNR760 conjugated to RhB. FI of RhB solution without GNPs is also included in the panel for comparison. (b) Count rate histograms of GNS, GNR690, and GNR760 conjugated to SRB. FI of SRB is included in the panel for comparison. (c) Count rate histograms of GNS, GNR690, and GNR760 conjugated to Flu. FI of Flu is included in the panel for comparison. All solutions contained a fluorophore concentration of 1 μM. All measurements for a given fluorophore are obtained under identical conditions, set-up, and excitation power. Reprinted from: Nano Research, “An Ultra-Sensitive Dual-Mode Imaging System Using Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence in Solid Phantoms”, Vol. 8(12), 2015, p. 3917, Barnoy EA, Fixler D, Popovtzer R, Nayhoz T, Ray K, with permission of Springer.

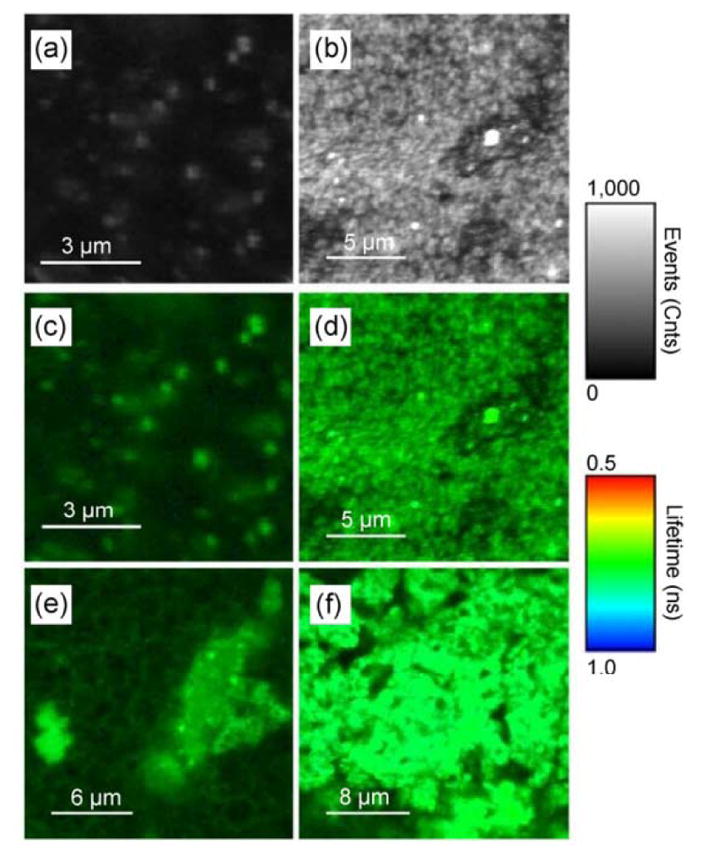

FI results for phantoms containing RhB are shown in Figure 4. The corresponding FLIM images for the other fluorophores can be seen in our work1. Following the same pattern as for the solutions, the phantoms also displayed a fluorophore-dependent MEF signal. Flu constructs resulted in poor fluorescent probes, but in GNP to RhB or SRB constructs, much brighter regions were detected within the phantoms. Such strong signals mean that more sensitive measurements can be performed.

Figure 4.

FLIM images of RhB-based phantoms. Depicting only FI (shown in counts of fluorescence events), the images show phantoms containing (a) RhB only and (b) GNS-RhB. Combining FI (shown as brightness) and FLT (shown as color), the images show phantoms containing (c) RhB only, (d) GNS-RhB, (e) GNR690- RhB, and (f) GNR760-RhB. For all images, the gray (brightness) scale bar represents FI in counts per millisecond. The color scale bar displays the FLT range in ns. All images are obtained under identical conditions, set-up, and excitation power. Reprinted from: Nano Research, “An Ultra-Sensitive Dual-Mode Imaging System Using Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence in Solid Phantoms”, Vol. 8(12), 2015, p. 3918, Barnoy EA, Fixler D, Popovtzer R, Nayhoz T, Ray K, with permission of Springer.

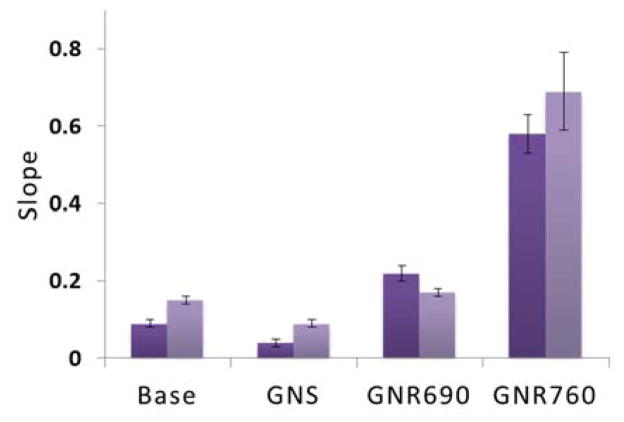

The DR system was used to measure GNP presence in phantoms containing the different GNPs. Following previously discussed procedures, the intensity of light scattered out of the phantoms was measured over varying light source-detector separation distances using excitation light sources of 650nm and 780nm. Also as explained previously, finding the slope of the function relating this light and separation distance, it is possible to easily extract optical properties of the sample. The slopes corresponding to phantoms containing water only and each geometry of GNP as obtained from the 780nm light source are shown in Figure 5. The greater slopes reveal stronger particle absorption, and as can be expected, for this incident light the GNRs of AR 3.3, GNR760, most significantly affected the slope. Note that the incident light’s long wavelengths treat the conjugated fluorophores as transparent.

Figure 5.

Diffusion reflection (DR) results using a 780nm light source, with phantoms measured containing water only (“Base”), and each of the 3 GNP geometries considered. The “Slope” refers to the linear relationship between the intensity of scattered light and the separation distance between light source and detector in the DR system. Each phantom was measured twice, as indicated by the 2 columns.

4. DISCUSSION

We developed simple-to-manufacture and biocompatible probes using GNPs conjugated to fluorescent dyes, which can serve as contrast agents to simple, sensitive, non-invasive, and safe techniques. FLIM provided surface fluorescence information, while DR detected GNP optical properties within phantom volumes. We detected MEF with 2 of the fluorophores, which absorbed at wavelengths corresponding to the GNP plasmon resonances, while the third fluorophore, absorbing at shorter wavelengths, was quenched. Detecting MEF with GNRs in itself is already relatively novel in current literature.

Through the current work, we demonstrate the initial steps of a dual-modal imaging system, where the FLIM and DR systems are able to effectively detect GNP presence in tissue-imitating phantoms. Our system is highly sensitive due to the increased intensity provided by MEF, and also because of the inherent sensitivity of both FLIM and DR. Together, these two modalities and MEF can provide a lot of meaningful information for molecular and functional imaging of biological samples. In the future it will be possible to create probes that not only quench and then unquench to create a signal, but that could start quenched and then advance to enhanced fluorescence in specific biological conditions. Then, the FLIM system would be able to easily detect the ongoing function, while DR would reveal the GNP locations, combining into a sensitive structural-functional imaging pair.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this manuscript was supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Nos. AI087968 and NIGMS R01GM117836 (K.R.)). The authors also thank Dr. J. Lakowicz for the access granted to the FLIM systems in the Center for Fluorescence Spectroscopy.

References

- 1.Barnoy EA, Fixler D, Popovtzer R, Nayhoz T, Ray K. An Ultra-Sensitive Dual-Mode Imaging System Using Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence in Solid Phantoms. Nano Res. 2015;8(12):3912–3921. doi: 10.1007/s12274-015-0891-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eghtedari M, Liopo AV, Copland JA, Oraevsky AA, Motamedi M. Engineering of Hetero-Functional Gold Nanorods for the in Vivo Molecular Targeting of Breast Cancer Cells. Nano Lett. 2009;9:287–291. doi: 10.1021/nl802915q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Maltzahn G, Park J, Agrawal A, Bandaru NK, Das SK, Sailor MJ, Bhatia SN. Computationally Guided Photothermal Tumor Therapy Using Long-Circulating Gold Nanorod Antennas. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):3892–3900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Sayed MA. Some Interesting Properties of Metals Confined in Time and Nanometer Space of Different Shapes. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34(4):257–264. doi: 10.1021/ar960016n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain PK, Lee KS, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Calculated Absorption and Scattering Properties of Gold Nanoparticles of Different Size, Shape, and Composition: Applications in Biological Imaging and Biomedicine. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110(14):7238–7248. doi: 10.1021/jp057170o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Yu J, Birch DJS, Chen Y. Gold Nanorods for Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging in Biology. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(2):020504. doi: 10.1117/1.3366646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker W. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging--Techniques and Applications. J Microsc. 2012;247(2):119–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2012.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subhash N, Mallia JR, Thomas SS, Mathews A, Sebastian P, Madhavan J. Oral Cancer Detection Using Diffuse Reflectance Spectral Ratio R540/R575 of Oxygenated Hemoglobin Bands. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11(1):014018. doi: 10.1117/1.2165184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurdy J, Jay G, Suner S, Crawford G. Photonics-Based in Vivo Total Hemoglobin Monitoring and Clinical Relevance. J Biophotonics. 2009;2(5):277–287. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200910019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ankri R, Taitelbaum H, Fixler D. Reflected Light Intensity Profile of Two-Layer Tissues: Phantom Experiments. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16(8):085001. doi: 10.1117/1.3605694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ankri R, Taitelbaum H, Fixler D. On Phantom Experiment of the Photon Migration Model in Tissues. Open Opt J. 2011;5(2):28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ankri R, Duadi H, Motiei M, Fixler D. In-Vivo Tumor Detection Using Diffusion Reflection Measurements of Targeted Gold Nanorods - a Quantitative Study. J Biophotonics. 2012;5(3):263–273. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201100120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ankri R, Ashkenazy A, Milstein Y, Brami Y, Olshinka A, Goldenberg-Cohen N, Popovtzer A, Fixler D, Hirshberg A. Gold Nanorods Based Air Scanning Electron Microscopy and Diffusion Reflection Imaging for Mapping Tumor Margins in Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. ACS Nano. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakowicz JR. Radiative Decay Engineering 5: Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence and Plasmon Emission. Anal Biochem. 2005;337(2):171–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fixler D, Nayhoz T, Ray K. Diffusion Reflection and Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy Study of Fluorophore-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles or Nanorods in Solid Phantoms. ACS Photonics. 2014;1(9):900–905. doi: 10.1021/ph500214m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]