Abstract

Objectives

We investigated the demographic characteristics, clinical and laboratory findings, treatment strategies and clinical outcomes of patients presenting at emergency department (ED) with digoxin levels at or above 1.2 ng/ml.

Materials and methods

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with serum digoxin levels at or above 1.2 ng/ml admitted to an ED between January 2010 and July 2011 were investigated in this cross-sectional descriptive study. Patients with ECG and clinical findings consistent with digoxin toxicity and no additional explanation of their symptoms were evaluated for digoxin toxicity.

Results

In this study 137 patients were included, and 68.6% of patients were women with mean age 76.1 ± 12.2. There was no significant difference between gender and digoxin intoxication. The mean age of intoxicated group was significantly higher than the non-intoxicated group (P = 0.03). The most common comorbidities were congestive heart failure (n = 91) and atrial fibrillation (n = 74). The most common symptoms were nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. The levels of hospitalization and mortality in this group were significantly higher.

Conclusion

Digoxin intoxication must be suspected in patients present in the ED, particularly those with complaints that include nausea and vomiting, as well as new ECG changes; serum digoxin levels must be determined.

Keywords: Digoxin, Digoxin level, Intoxication, Emergency department

1. Introduction

Despite the introduction of new drug classes for managing congestive heart failure (CHF) and atrial fibrillation (AF), many patients admitted to emergency departments (EDs) continue to be managed with cardiac glycosides. Cardiotoxicity from cardiac glycosides may present obvious symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and hypotension, or may be more subtle with nonspecific symptoms.1 The difficulty in diagnosing patients with digitalis intoxication can be attributed to several factors: 1) the signs, symptoms and electrocardiogram (ECG) manifestations can be attributed to the underlying disease process for which the drug is prescribed; 2) the narrow therapeutic window of digoxin, which causes great variability in the sensitivity of individuals toward the drug; 3) the lack of any dysrhythmia diagnostic of toxicity.2, 3 Chronic toxicity occurs in 4–10% of the patients taking digitalis but is suspected in only 0.25% of all cases4, 5

Few studies have probed the incidence of toxicity and the factors that affect the toxicity observed among patients presenting to ED, despite the clinical importance of digoxin toxicity. We enacted this cross-sectional retrospective study to investigate the demographic characteristics, clinical and laboratory findings, treatment strategies and clinical outcome of patients presenting at our ED whose digoxin levels were 1.2 ng/ml or above. The threshold 1.2 ng/ml is adopted because of the reported increased mortality above 1.2 ng/ml in the study of Rathore et al.6

2. Materials and methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive review included the cases with digoxin levels at or above 1.2 ng/ml at an ED between January 2010 and July 2011. The study population was selected from the hospital information system according to their digoxin levels regardless of the presenting clinical symptoms or findings. Patients with missing data were excluded from the study.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The day of admittance (day/month/year), as well as the ages, genders, states of acute or chronic drug intake, comorbidities, clinical findings, test results (ECG, as well as laboratory findings for glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, sodium, potassium, chlorine, complete blood count, CK-MB, troponin), treatment information, blood digoxin levels and clinical outcomes, of the patients were recorded using standard data forms.

Patients with ECG and clinical findings consistent with digoxin toxicity and for whom there was no additional explanation of symptoms were evaluated as suffering from digoxin toxicity. Digoxin toxicity was studied based on acute or chronic usage, as listed below.

Acute toxicity is indicated by the following:

-

1.

The presence of dysrhythmias, dysrhythmias with decreased AV conduction or/and increased automaticity (e.g., AF with AV block, accelerated junctional rhythm), premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) (particularly bigeminy or trigeminy) or supraventricular tachyarrhythmias with rapid ventricular rates.7

-

2.

Hyperkalemia (≥5.5 mEq/L).8

-

3.

Probable clinical findings other than cardiac findings.3

Chronic toxicity is indicated by the following:

-

1.

Bradyarrhythmias (may be ventricular tachyarrhythmias)

-

2.

Normal to low serum potassium levels (may be high)8

-

3.

Increased serum digoxin levels (expected therapeutic level <1.2 ng/ml)6

-

4.Probable clinical findings other than the cardiac findings include the following;

-

a.Weakness

-

b.Gastrointestinal system: anorexia, nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain

-

c.Central nervous system: headache, thoughtfulness, hallucinations, delirium or photophobia, visual disturbances (yellow-green dyschromatopsia)3

-

a.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The data recorded in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 16 for Windows statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The qualitative variables are expressed as a % and the estimation of 95% confidence interval (CI). The quantitative variables are expressed as the mean ± S.D. The means were compared using Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test as applicable after verifying normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The association of qualitative variables was made using the Chi-square test. Test results with p values <0.05 were determined to be statistically significant.

3. Results

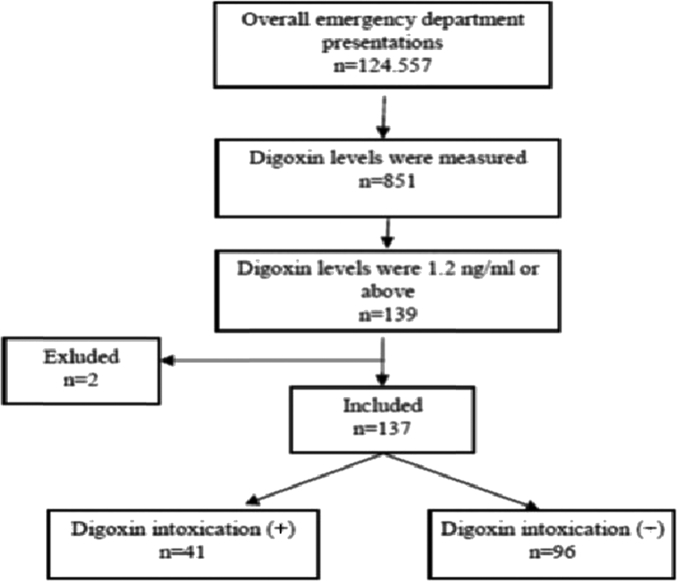

During the study period, 124.557 patients arrived at the ED; 139 patients had digoxin levels 1.2 ng/ml or higher. Two of the patients were excluded from the study due to a lack of data, and 137 patients were included. The patients included in the study accounted for 0.11% of the patients who arrived at the ED during the study period (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for the study population.

Among the patients included in the study, 43 (31.4%) were male, and 94 (68.6%) were female; the mean age was 76.1 ± 12.2. The youngest patient was 20, and the oldest patient was 104 years old. Two (1.5%) patients arrived after acute oral intake, one patient (0.7%) had with acute exposure during chronic intake and 134 (97.8%) patients were chronic users. The mean ages of the patients with acute and chronic intake were 57.5 ± 50.2 and 76.3 ± 11.3, respectively. There was no significant difference between the age groups (P > 0.05). Digoxin was the only drug taken by 135 (98.5%) of the patients. The exposures occurred with oral intake.

When evaluated using the clinical, laboratory and ECG findings, 29.9% (n = 41) of patients were considered to have digoxin toxicity, and 70.1% (n = 96) of the patients only had high blood digoxin levels but were not intoxicated. In the intoxicated group, one patient presented with acute toxicity, and 39 presented with chronic toxicity. There was no significant difference between the intoxicated and non-intoxicated groups in the context of gender (P > 0.05). The mean age of intoxicated group was significantly higher than that of the non-intoxicated group (79.8 ± 11.8 and 74.6 ± 12.1, respectively, P = 0.03). No significant differences were found between the comorbid diseases of the patients and digoxin toxicity (Table 1).

Table 1.

The relationship between elevated digoxin levels and comorbid diseases.

| Comorbid disease | Digoxin toxicity |

p | X2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | % | No | % | |||

| CHF | 27 | 65.9 | 64 | 66.7 | >0.05 | 0.03 |

| AF | 26 | 63.4 | 48 | 50 | >0.05 | 2.75 |

| HT | 23 | 56.1 | 48 | 50 | >0.05 | 0.73 |

| CAD | 13 | 31.7 | 27 | 28.1 | >0.05 | 0.29 |

| Other | 10 | 24.4 | 37 | 37.5 | >0.05 | 2.17 |

| DM | 9 | 21.9 | 22 | 22.9 | >0.05 | 0.01 |

| Cardiac valve disease | 4 | 0.9 | 14 | 14.6 | >0.05 | 0.49 |

We found that the most common final diagnoses other than digoxin intoxication were CHF (n = 24, 17.5%) and acute renal failure (n = 13, 9.4%). Sixteen (11.6%) patients had more than one diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

The final diagnoses of patients other than that of digoxin intoxication by system.

| System | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 31 | 22.6 |

| Pulmonary | 18 | 13.1 |

| Genitourinary | 16 | 11.6 |

| Gastrointestinal | 12 | 8.7 |

| Neurological | 7 | 5.1 |

| Other | 34 | 24.8 |

The potassium level is significantly higher in the intoxicated group when the biochemical markers are evaluated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Laboratory values in both intoxicated and non-intoxicated patients.

| Digoxin intoxication | Yes |

No |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | N | Mean | P | |

| Blood digoxin (ng/ml) | 41 | 3.35 | 96 | 1.7 | 0.00 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 41 | 43.5 | 95 | 35 | >0.05 |

| creatinine (mg/dl) | 41 | 1.8 | 95 | 1.5 | >0.05 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 41 | 135.5 | 95 | 135.5 | >0.05 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 41 | 5.0 | 95 | 4.5 | <0.05 |

| Chloride (mmol//L) | 41 | 103.9 | 95 | 102.7 | >0.05 |

| White blood cell (10X103/L) | 41 | 10.8 | 95 | 11.2 | >0.05 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 40 | 138.8 | 92 | 156.9 | >0.05 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 41 | 11.8 | 94 | 11.8 | >0.05 |

| CKMB (ng/ml) | 35 | 2.4 | 78 | 2.8 | >0.05 |

| Troponin (ng/ml) | 35 | 0.3 | 78 | 0.3 | >0.05 |

In the intoxicated group, the most common diagnoses included cardiac symptoms and the most common symptoms included nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, altered mental status and visual disturbances, respectively (35%; 27.5%; 20%; 7.5%).

Moreover, of the 41 patients with digoxin intoxication, 11 (26.8%) displayed no ECG changes, and 17 (41.5%) had new ECG findings. Past ECGs could not be found for 13 (31.7%) patients. Of the 96 non-intoxicated patients, 73 (76.1%) displayed no ECG changes, and 7 (7.3%) patients had new ECG findings. Past ECGs could not be found for 16 (16.6%) patients. AF with slow ventricular rates, sinus bradycardia and PVCs were significantly more common in intoxicated patients, while AF with a rapid ventricular rate was significantly more common in non-intoxicated patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

ECG findings for intoxicated and non-intoxicated patients.

| ECG finding | Digoxin intoxication |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | % | No | % | P | X2 | |

| AF with slow ventricular rate | 19 | 46.3 | 3 | 3.1 | <0.01 | 41.43 |

| AF with normal ventricular rate | 11 | 26.8 | 37 | 37.5 | >0.05 | 1.73 |

| Left bundle branch block | 6 | 14.6 | 12 | 12.5 | >0.05 | 0.17 |

| PVCs | 5 | 12.2 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.03 | 8.90 |

| Normal | 4 | 9.8 | 14 | 14.6 | >0.05 | 0.59 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 3 | 7.3 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.04 | 4.18 |

| Right bundle branch block | 2 | 4.8 | 2 | 2.2 | >0.05 | 0.86 |

| Sinus tachycardia | 1 | 2.4 | 9 | 9.4 | >0.05 | 2.04 |

| Atrial premature beat | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.1 | >0.05 | 0.43 |

| First degree AV block | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | >0.05 | 2.43 |

| Second-third degree AV block | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | >0.05 | 0.41 |

| AF with rapid ventricular rate | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20.8 | <0.01 | 9.65 |

| Atrial flutter | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | >0.05 | 0.42 |

Bold: Statistically significant values (p<0.05).

In the intoxicated group, the treatment modalities were assessed. Coexisting diseases were treated in 18 patients (43.9%). Supportive treatment was administered to 15 patients (36.6%). Eleven patients (26.8%) were treated by pacemaker. Gastric lavage and active charcoal was administered to one patient (2.4%).

During our study, 10.2% of patients died in the ED, while 21.9% were admitted to intensive care units (Table 5). There were significant differences in the hospitalization, discharge and death of the intoxicated versus the non-intoxicated patients (p < 0.001). Hospitalization was significantly more common among intoxicated patient. However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the context of the final clinical courses (p = 0.82).

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes of the patients in the ED.

| Clinical outcomes | Digoxin intoxication (+) |

Digoxin intoxication (−) |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Discharged | 12 | 29.3 | 56 | 58.3 | 68 | 49.6 |

| Admitted to intensive care unit | 20 | 48.8 | 10 | 10.4 | 30 | 21.9 |

| Admitted to others services | 4 | 9.8 | 15 | 15.6 | 19 | 13.9 |

| Death | 4 | 9.8 | 10 | 10.4 | 14 | 10.2 |

| Self-discharge/refused the treatment | 1 | 2.3 | 5 | 5.3 | 6 | 4.4 |

Among the hospitalized patients in the intoxicated group; two of them died, and 20 of them were discharged. The clinical courses of 3 patients could not be found. Among the hospitalized patients in the non-intoxicated group, 19 were discharged, 5 patients died and the clinical courses of 6 patients could not be found. There were significant differences in the hospitalizations, discharges and deaths between the intoxicated and non-intoxicated patients (p < 0.001). Hospitalization was significantly more common among the intoxicated patients. However, there was no significant difference between two groups relative to the final clinical courses (Chi-square:0.39; p = 0.82).

Regarding the final clinical outcomes of the patients, 107 (78.1%) were discharged from the hospital, and 21 (15.3%) died. Among the patients who died, 14 patients died in the ED, and 7 patients died during hospitalization. All patients who died were chronic digoxin users. The outcomes of 9 (6.6%) patients could not be found.

4. Discussion

The incidence of digoxin toxicity has declined recently due to the decreased use of digoxin while treating heart failure and arrhythmias, fast and accurate detection of drug levels and increased awareness of the interactions between digoxin and other drugs. Haynes et al reported a decrease in digoxin intoxication related to the decreased use of digoxin between 1994 and 2004 in the USA.5 The American Association of Poison Control Centers reported 2610 toxic digoxin exposures in 2006, and this number was 2550 in 2009.9 Budnitz et al found that every arrival to the ED was drug related among patients more than 65 years old. Moreover, 3.1% of the patients were using digoxin, and 0.024% were diagnosed with digoxin intoxication in the same study.10 Aarnoudse et al reported in a study in which all presentations to the hospital were evaluated that 0.04% of all presentations were attributed to digoxin intoxication.11 In our study, the patients for whom digoxin levels had been obtained accounted for 0.068% of all presentations to the ED. Similarly, patients who were diagnosed with digoxin intoxication accounted for 0.032% of the patients who arrived at the ED at the same time. This ratio was similar to that in the other studies.

Digoxin related emergency admissions are significant causes of drug-related presentations to the ED, particularly among the elderly. Budnitz et al reported that the probability of hospitalizations related to drugs was 7-fold higher in patients above 65 years of age.10 In another study, Butnitz et al evaluated drug related ED presentations in patients older than 65, finding that the most common drug related presentations were attributed to warfarin, insulin and digoxin; these three drugs were 35-fold more common among ED presentations because they are frequently prescribed.12 Miura et al found an increased sensitivity toward digoxin with increasing age.13 During our study, the mean age of the patients was 76.1 ± 12.2. Because digoxin use is more common among the elderly, this result was expected. The mean ages of the digoxin-intoxicated and non-intoxicated groups were 79.8 ± 11.8 and 74.6 ± 12.1, respectively. The mean age of the intoxicated group was significantly higher (p = 0.03). This result supports other studies showing that digoxin toxicity increases with age.10, 12, 13, 14

Response toward digoxin treatment differs between genders. Digoxin-related deaths are more common in females.15 Aarnoudse et al reported that digoxin intoxication was 1.4-fold higher among women while studying patients hospitalized related to digoxin intoxication.11 In our study, 73.2% of the intoxicated group was female. No significant difference was found between digoxin intoxication and gender. However, we believe that the risk of digoxin intoxication must be considered for every woman using digoxin. Studies using a sex-separated genotype might elucidate the sensitivity toward intoxication before use.

The majority of digoxin intoxications occurred in chronic digoxin users. Pita-Fernandez et al found that most exposures were due to taking an inappropriate dose of the drug; and only 4.8% of the cases arose from accidentally intake.16 Suicidal drug ingestion is commonly reported in the literature.17, 18 According to Antman and al, among 150 life-threatening digoxin intoxications, 50% of the patients were long-term users, 10% of the patients took digoxin accidentally, while 39% of patients took digoxin with suicidal intent.19 In our study, 1.5% of the patients presented with acute intake, 0.7% with acute exposure during chronic intake and 97.8% were chronic users. In the intoxicated group, 95% were chronic users, 2.4% presented with acute intake and 2.4% presented with acute exposure during chronic intake. These results were similar to those of Pita-Fernandez et al but the rate of acute intake was much lower compared to the study of Antman et al. Unsurprisingly, Antman et al reported more acute intakes because they investigated life-threatening digoxin intoxications. The ages of the patients with acute intake ranged from 22 to 93, and the digoxin levels were 12.2 ng/ml and 1.42 ng/l, respectively. Only one of their results was consistent with digoxin intoxication. We found that type of exposures had a significant effect on blood digoxin levels but had no effect on any other laboratory parameters.

Digoxin is usually used to control AF and CHF. Digoxin is safe, particularly in males with decreased left ventricle function.15, 18 Cardiac valvulopathy was detected in 81% of patients, HT was found in 68.3% and ischemic heart disease was found in 46.3% in the study by Pita-Fernandez et al; these researchers evaluated digoxin intoxications in the elderly in EDs.16 We found that 66% of patients had CHF, and 63% had AF among the digoxin intoxicated patients. This was an expected result because CHF and AF are the most common indications for digoxin use. We could not detect the prevalence of valvulopathy possibly because our study was retrospective, precluding further examinations.

Mahdyoon et al reported that 43 patients had definite diagnoses of digoxin intoxication, while 52% of patients had nausea, while 48% suffered from vomiting in a study including 219 patients discharged from a hospital with a diagnosis of digital intoxication.20 Nausea and vomiting were the most common complaints in the study by Pita-Fernandez et al.16 In our study, the most common symptoms among the 41 digoxin intoxicated patients were nausea and vomiting (35%), as well as abdominal pain (27.5%), similar to the literature.

ECG findings are critical for diagnosing and treating digoxin toxicity. There are differences between the ECG findings in various studies. Ma et al reported that the most common ECG finding was PVCs.7 Mahdyoon et al found the most common ECG findings were AV block (66%) and sinus bradycardia (26%).20 Pita-Fernandez et al found that, among 42 digoxin intoxicated patients, the most common ECG finding was AF (85%), and 45% of the patients had a the heart rate below 60/min.16 In our study the most common ECG findings were AF with a slow ventricular rate (46.3%), AF with normal ventricular rate (26.8%) and left bundle branch block (14.6%), respectively. PVCs were detected in 12.2% of the patients. Compared to non-intoxicated patients, sinus bradycardia, AF with a slow ventricular rate and PVCs were significantly more common in the digoxin intoxicated group. Ordog et al found that among 5100 patients using digoxin, 65 patients had new ECG changes consistent with digoxin toxicity.21 In our study, 41.5% of patients had new ECG changes. ECG changes were more common in our study because we only investigated patients with elevated digoxin levels.

Digoxin is a safe antiarrhythmic agent in patients with AF according to the current literature. However, in many studies regarding the safety profile of digoxin, the observation period is short, and patients with CHF were excluded from the study.22 However, long-term studies are needed to evaluate the effects of the ECG changes on mortality and morbidity. We believe that digoxin levels must be observed in patients who use digoxin and who have sinus bradycardia after they arrive at the ED for any reason, AF with a slow ventricular rate or ventricular extra beats on the ECG and digoxin intoxication must be considered in the light of the laboratory and clinical findings.

The mean BUN levels were significantly higher in the intoxicated group, but there was no significant difference in the potassium levels of the intoxicated and non-intoxicated groups, as observed by Smith et al.23 Renal failure was more common in the intoxicated group, according to Beller et al.24 However, we did not find any significant difference regarding the BUN and creatinine levels between the two groups (Table 3).

The most common precipitating factor for digoxin intoxication was usually the decrease in potassium stores due to diuretic treatment and secondary hyperaldosteronism in patients with heart failure.25 Therefore, hypokalemia is more common in intoxication related to chronic digoxin treatment.2 The blood potassium levels were significantly higher in the intoxicated group during our study. Hyperkalemia is not expected during chronic digoxin intoxication unless there is simultaneous renal failure.2 However, most of the patients had chronic digoxin intoxication most likely due to the frequent use of thiazide diuretics in patients with CHF and HT; it is impossible to comment on the relationship between drugs and high potassium levels because these drugs were not assessed in our study.

Active charcoal administration and gastric lavage are the gastrointestinal decontamination methods used to counter many types of intoxications. The decontamination rates are lower in the poison papers by AACT and EAPCCT after 1997 because the guidelines for administering a gastric lavage and active charcoal were published after this date.26, 27 Active charcoal may be useful during the early stages of acute digoxin intake.28 Gastric lavage and active charcoal were administered to one patient in our study; this patient presented with acute digoxin toxicity. Most of the patients had chronic digoxin intoxication, and this result is consistent with the recent literature. One patient (0.7%) underwent hemodialysis for hyperkalemia. Because of their comorbid diseases or ongoing metabolic situations, 64.2% of patients (n = 88) received other therapies.

Different results have been reported in the literature regarding the prognosis of digoxin intoxication. No deaths were reported by Pita-Fernandez et al.16 However, 16% of the patients with digoxin intoxication observed by Pap et al and 41% of patients with digoxin intoxication observed by Mahdyoon et al died.14, 20 In our study, in-hospital mortality occurred for 15% of the digoxin intoxicated group. The different mortality rates in these studies can be attributed to the heterogeneity of the patients with digoxin intoxication and the lack of standardized digoxin intoxication criteria. However, in our study there was a significant difference between two groups regarding the admission to care units or services, as well as discharge or death. Predicting the cause of mortality was difficult because digoxin intoxicated patients were often elderly and had co-existing diseases.

Pita-Fernandez et al reported that 78.6% of the patients with digoxin toxicity were hospitalized, while 85.7% of patients received only symptomatic treatment; there were no deaths in the ED.16 Ordog et al reported that 24% of the patients were evaluated and treated in the ED, and the others were hospitalized.21 In our study, 29.3% of patients were treated in the ED, 9.8% of patients died in the ED and 58.6% of the patients were admitted to the hospital. In addition, 48.8% of the hospitalized patients were admitted to intensive care units. The rate of patients treated in the ED was similar to that of Ordog et al, but the rate of hospitalization was lower, indicating that a number of patients who should have been hospitalized were treated in the ED.

5. Conclusions

We concluded that digoxin intoxication must be suspected in patients presenting to the ED, particularly those complaining of nausea and vomiting and exhibiting new electrocardiographic changes. In these cases, the serum digoxin levels must be assessed.

Acknowledgments

GL made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition and interpretation of data. GE made substantial contributions to the conception and design, was involved in drafting the manuscript. NCO made substantial contributions to the design, the analysis and interpretation of data, and was involved in drafting the manuscript. BB made substantial contributions to the conception and design, and the analysis and interpretation of data. OL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and was involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey.

References

- 1.Gheorghiade M., van Veldhuisen D.J., Colucci W.S. Contemporary use of digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation. 2006;113:2556–2564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.560110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle JS, Kirk MA. Digitalis glycosides. In: Tintinalli JE, Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine, a Comprehensive Study Guide, 7th ed., New York, McGraw Hill. pp 1260–1264.

- 3.Kardiyak glikozidlerle zehirlenmeler. In; T.C. Saglık Bakanlıgı Birinci Basamaga Yonelik Zehirlenmeler Tanı ve Tedavi Rehberleri 2007 (The ministry of Health of Turkey, Guidelines of diagnosis and treatment of intoxication for primary care hospitals 2007). Editor in chief; Tuncok Y, Kalyoncu NI. pp 73–77.

- 4.Roberts JD. Cardiovascular drugs. In: Marx AJ, Rosen's Emergency Medicine, Concepts and Clinical Practice, 7th ed., Philadelphia, Mosby Elsevier, pp 1978–1982.

- 5.Haynes K., Heitjan D., Kanetsky P. Declining public health burden of digoxin toxicity from 1991 to 2004. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:90–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rathore S.S., Curtis J.P., Wang Y. Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2003;289:871–878. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma G., Brady W.J., Pollack M. Electrocardiographic manifestations: digitalis toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(00)00312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manini A.F., Nelson L.S., Hoffman R.S. Prognostic utility of serum potassium in chronic digoxin toxicity: a case-control study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2011;11:173–178. doi: 10.2165/11590340-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronstein A.C., Spyker D.A., Cantilena L.R. 2009 Annual report of the the American Association of Poison Control Centers' national poison data system (NPDS): 27th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:979–1178. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.543906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budnitz D.S., Pollock D.A., Weidenbach K.N. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296:1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarnoudse A.L., Dieleman J.P., Stricker B.H. Age- and gender-specific incidence of hospitalisation for digoxin intoxication. Drug Saf. 2007;30:431–436. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budnitz D.S., Shehab N., Kegler S.R. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:755–765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura T., Kojima R., Sugiura Y. Effect of aging on the incidence of digoxin toxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:427–432. doi: 10.1345/aph.19103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pap C., Zacher G., Karteszi M. Prognosis in acute digitalis poisoning. Orv Hetil. 2005;146:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathore S.S., Wang Y., Krumholz H.M. Sex-based differences in the effect of digoxin for the treatment of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1403–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pita-Fernandez S., Lombardia-Cortina M., Orozco-Veltran D. Clinical manifestations of elderly patients with digitalis intoxication in the emergency department. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53:e106–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Calvo M.S., Rico R., Lo pez-Rivadulla M. Report of suicidal digoxin intoxication: a case report. Med Sci Law. 2002;42:265–268. doi: 10.1177/002580240204200313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranquin R., Parizel G. Massive digoxin intoxication. Report of a case with serum digoxin level correlation. Acta Cardiol. 1975;30:375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antman E.M., Wenger T.L., Butler V.P., Jr. Treatment of 150 cases of life-threatening digitalis intoxication with digoxin-specific Fab antibody fragments. Final report of a multicenter study. Circulation. 1990;81:1744–1752. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.6.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahdyoon H., Battilana G., Rosman H. The evolving pattern of digoxin intoxication: observations at a large urban hospital from 1980 to 1988. Am Heart J. 1990;120:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90135-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ordog G.J., Benaron S., Bhasin V. Serum digoxin levels and mortality in 5100 patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:32–39. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(87)80281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamargo J., Delpon E., Caballero R. The safety of digoxin as a pharmacological treatment of atrial fibrillation. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5:453–467. doi: 10.1517/14740338.5.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith T.W., Haber E. Digoxin intoxication: the relationship of clinical presentation to serum digoxin concentration. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:2377–2386. doi: 10.1172/JCI106457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beller G.A., Smith T.W., Abelmann W.H. Digitalis intoxication. A prospective clinical study with serum level correlations. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:989–997. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197105062841801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V. Digitalis toxicity. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/154336 (achieved at 05.01.2012).

- 26.AACT and EAPCCT Position paper: single dose activated charcoal. Clin Toxicol. 2005;43:61–87. doi: 10.1081/clt-200051867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.AACT and EAPCCT Position paper: gastric lavage. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:933–943. doi: 10.1081/clt-200045006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts D.M., Buckley N.A. Antidotes for acute cardenolide (cardiac glycoside) poisoning. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:18. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005490.pub2. CD005490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]