Abstract

Background/Objectives

For-profit agencies comprise the majority of all United States hospice agencies, prompting concerns about aggressive enrollment practices and deficient care. Using detailed administrative data from 2005–2011, we sought to assess differences in patient populations and service use by hospice ownership, chain status, and agency size.

Design/Participants

Retrospective cohort study of 5,405,526 Medicare beneficiaries age 65+ enrolled in hospice during 2005–2011. Hospice use by ownership category (for-profit non-chain and chain, not-for-profit non-chain and chain, government) and agency size (0–50 patients, 51–200, 201–400, 401+). Mean length-of-use, stays ≤3 days, stays ending with live discharge, and decedents receiving no general inpatient care (GIP) or continuous home care (CHC) level hospice in the last 7 days of life.

Results

After adjusting for patient and geographic differences, for-profit non-chain and chain agencies had longer mean lengths-of-use (84.5 and 91.2 days, respectively) than other agency types (66.3–72.5 days); higher rates of live discharge (21.0% and 20.2% versus 14.6%–15.9%); and lower proportions of stays of ≤3 days (13.9% and 14.7% versus 16.6%–17.5%) (all p-values<0.001). The proportion of decedents not receiving GIP/CHC level care before death was highest among for-profit chains (75.9%) and lowest among not-for-profit non-chains (63.2%). Across ownership categories, smaller agencies had longer mean lengths-of-use, higher live discharge rates, lower rates of stays ≤3 days, and higher rates of patients receiving no GIP/CHC level care. Considerable variation in patient traits and unadjusted service use existed among the nation’s largest chains.

Conclusion

Although for-profit and not-for-profit hospice agencies differ along key dimensions, our results convey substantial heterogeneity within these categories, highlighting the need to consider factors such as agency size and chain affiliation in understanding variations in Medicare beneficiaries’ hospice care.

INTRODUCTION

The recent Institute of Medicine report Dying in America concluded that the provision of end-of-life care in the United States requires substantial changes.(1) Although the report looks well beyond the Medicare hospice benefit in identifying levers to effect positive change, it outlines several challenges that face hospice and threaten its long-run viability, including the substantial transformation in Medicare’s hospice patients and providers over the benefit’s three-decade history and shortcomings of its static approach to eligibility and payment.

One of the biggest flashpoints in recent hospice policy discussions is the increasing role of for-profit providers. Hospice in the United States began almost exclusively as a not-for-profit enterprise, but for-profit agencies have played a more prominent role over the past decade and now comprise the majority of all hospice agencies.(2) Spurred by media reports alleging aggressive enrollment practices and deficient care, President Obama recently signed into law bipartisan legislation (the IMPACT Act of 2014) that included provisions to bolster hospice oversight.(3)

An emerging research literature has explored the role of ownership in hospice, primarily focusing on aggregate differences in patient populations and service use between for-profit and not-for-profit agencies. These studies generally have found that, relative to not-for-profit, for-profit agencies disproportionately enroll nursing home residents and patients with non-cancer diagnoses and that their patients tend to have longer lengths-of-use.(2, 4–7) Studies have found that for-profit agencies have higher rates of live discharge, utilize fewer skilled staff, and provide a narrower range of clinical services relative to not-for-profits.(8–11) A recent survey-based study reported that for-profit agencies provide less charity care and fewer training opportunities than not-for-profits, while also engaging in greater outreach to minority and low-income communities.(12)

Comparing hospice agencies on profit status alone is a useful starting point to consider the role of ownership, but it conveys little about the impact of other structural and organizational dimensions in the delivery of care. In particular, the distinctions of for-profit and not-for-profit encompass diverse organizations within each category. To investigate factors that could drive differences beyond profit status alone, prior studies have analyzed the impact of agency size and tenure in the marketplace, for instance finding that smaller and newer for-profit agencies have higher rates of live discharge and longer lengths of stay than other agencies.(11, 13, 14) Few analyses of hospice care have explored the role of the agencies’ parent companies. Analyses based on a national survey of hospice agencies included chain status as a control variable in examining for-profit vs. not-for-profit differences in enrollment practices and the provision of community benefits; (4, 15) another article using the same dataset examined the influence of chain status on self-reported care practices, finding that chain agencies (the article did not distinguish between for-profit and not-for-profit chains) generally offered higher quality of care relative to non-chains. (12) To date, the literature has not comprehensively studied the patients and actual service provision of the diverse for-profit and not-for-profit chains that now serve around half of all United States hospice enrollees.(16)

In this paper, we assess differences in patient populations and service use by hospice ownership categories, not only to compare for-profit and not-for-profit agencies but to examine care provided by the diverse companies operating in the hospice sector, which differ in size and in whether they are part of a chain. Although detailed hospice quality measures are not available from administrative data, we examined service use outcomes with potential relevance to quality of care. Our goal is to advance knowledge about whether and how ownership influences hospice provision and to offer insights about how this information is relevant to quality of care.

METHODS

Design Overview

The analyses focus on hospice use by Medicare beneficiaries age 65+ ending between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2011 and examine hospice enrollment and use trends for five broad ownership categories (For-profit non-chain and chain agencies, Not-for-profit non-chain and chain agencies, and government-owned agencies) and hospice agency size. The study links hospice agency ownership information from Medicare Cost Reports, beneficiary hospice use and agency identification from Medicare hospice claims, beneficiary demographic information from Master Beneficiary Summary files, and dates of nursing home residence from the Minimum Data Set.

Data and Variables

We use Medicare Cost Reports to obtain ownership information for all Medicare-certified hospice agencies. In addition to freestanding agencies, we capture ownership information for hospice agencies listed as sub-providers in cost reports for hospitals, home health agencies, and skilled nursing facilities. We code each hospice agency as for-profit, not-for-profit, or government-owned and as non-chain or chain (i.e., part of a company owning more than 1 agency). For chain-owned agencies, we code the individual chains to which they belong to track their role over time. We calculated hospice size based on the number of discharged patients served in each calendar year.

We use the Master Beneficiary Summary file to obtain a hospice user’s gender, age, race, and date of death. We use Medicare hospice claims to determine the dates of service use, the geographic region in which services are received, a hospice user’s terminal diagnosis, and the payment category into which each day of hospice falls (i.e., routine home care (RHC), continuous home care (CHC), inpatient respite care (IRC), and general inpatient care (GIP)). For hospice stays that begin in 2004 and end in a later study year, we incorporate the 2004 start date. We use the Minimum Data Set to identify dates of nursing home residence for hospice users, where applicable.

The key service use outcomes are: i) mean and median length-of-use, to convey differences in patient populations and the extent to which hospice agencies may target longer-stay patients, who are generally more profitable in the context of per-diem hospice payments(17); ii) percent of stays ≤3 days, to convey the prevalence of very short stays where patients may be unable to benefit clinically from the transition to hospice(18, 19); iii) percent of stays that end with live discharge, to convey the extent to which individuals disenroll from hospice before death, high rates of which could indicate problems in assessing eligibility and delivering high-quality patient care(11); and iv) percent of decedents who have no GIP or CHC level hospice care in the last 7 days of life, to convey the extent to which agencies did not provide care in the two most staff-intensive payment categories at the end of patients’ lives, possibly reflecting deficiencies in care.(20) Recognizing the skewed distribution of hospice length of use,(17) we also examined the percent of stays ≥ 180 days; the direction and magnitude of these differences were similar to mean and median length of use results and are not presented.

Statistical Analysis

We examine information on patient characteristics, including demographic traits (gender, age, and race); geographic region of service use; hospice diagnosis (cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), dementia, debility, and failure to thrive); nursing home residence, defined as having a hospice claim at any point during a nursing home stay; and the service use variables described above.

We present unadjusted service use information from for-profit and not-for-profit non-chain and chain agencies, by hospice agency size (number of discharged patients served per calendar year, categorized in four groups: 0–50 patients, 51–200, 201–400, and ≥401). Within ownership-size categories, we present information on the number of agencies and discharged patients and on the service use outcomes of interest. We also present patient traits and service use for the largest for-profit and not-for-profit chains in the United States marketplace in 2011, by enrollment.

We estimate regression models to assess the association between ownership type and service use outcomes. Although descriptive analyses include all hospice discharges, the regression models include the first hospice stay per patient only. Because we focus on service use across ownership types, it was important to exclude individuals recently discharged from hospice, as their inclusion could introduce bias if these patients were disproportionately cared for by certain ownership types. The models include as covariates age, gender, race/ethnicity, terminal diagnosis category, Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) enrollment status, region and urban/rural status of the area of service use, a discharge-year dummy variable, and the ownership type of the hospice agency. We model the dichotomous outcomes (having a stay ≤3 days, ending in live discharge, and having no GIP or CHC claims in the last 7 days of life) using logistic regression; we model mean length-of-use using ordinary least squares regression. We present adjusted values for outcomes across the ownership categories of interest. As a sensitivity analysis, we estimate models that also adjust for agency size category; these analyses produced similar results to the main findings and are not shown.

Finally, we estimate regression models for service use outcomes stratifying the results by agency size. Within each size category, we present adjusted results for each outcome across the ownership types using the specifications described above.

RESULTS

Hospice patient characteristics and unadjusted service use differed considerably across ownership categories over the 2005–2011 study period (Table 1). Compared to patients in other ownership categories, slightly higher proportions of patients served by for-profit non-chain and chain hospices were female and in the oldest age category (age 85+). Higher proportions of hospice patients served by for-profit non-chain and chain agencies were non-white; based in the South, especially for the for-profit chains; had non-cancer diagnoses, especially dementia; and lived in nursing homes. For-profit non-chain and chain hospice users had considerably longer lengths-of-use and higher rates of live discharge, on average.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics by Hospice Ownership Type, 2005–2011

| FP STAND ALONE | FP CHAIN | NFP STAND ALONE | NFP CHAIN | GOVT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| PATIENTS | 818,396 | 1,573,833 | 2,324,923 | 630,957 | 171,740 | |

| (%) | 15% | 29% | 43% | 12% | 3% | |

|

| ||||||

| SEX | Female | 60% | 61% | 58% | 58% | 57% |

| Male | 40% | 39% | 42% | 42% | 43% | |

| Mean | 83.1 | 83.3 | 82.7 | 82.7 | 82.4 | |

|

| ||||||

| AGE | 65–74 | 19% | 18% | 20% | 21% | 22% |

| 75–84 | 37% | 36% | 38% | 37% | 38% | |

| 85+ | 44% | 45% | 42% | 42% | 41% | |

|

| ||||||

| RACE | White | 88% | 85% | 91% | 91% | 91% |

| Black | 8% | 10% | 6% | 6% | 6% | |

| Other | 4% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 2% | |

|

| ||||||

| REGION | Northeast | 13% | 13% | 23% | 7% | 3% |

| Midwest | 20% | 20% | 28% | 24% | 28% | |

| South | 39% | 49% | 36% | 31% | 47% | |

| West | 27% | 18% | 14% | 37% | 22% | |

|

| ||||||

| HOSPICE DIAGNOSIS | Cancer | 29% | 26% | 37% | 36% | 36% |

| Dementia | 16% | 19% | 11% | 9% | 8% | |

| Debility | 11% | 11% | 9% | 11% | 9% | |

| Chf | 9% | 9% | 8% | 8% | 9% | |

| Copd | 7% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 7% | |

| Failure To Thrive | 6% | 8% | 5% | 5% | 6% | |

| Other | 22% | 20% | 24% | 24% | 26% | |

|

| ||||||

| SERVICE USE | LENGTH OF USE (Mean) | 92.7 | 104.1 | 67.6 | 72.0 | 66.4 |

| LENGTH OF USE (Median) | 24 | 23 | 15 | 17 | 17 | |

| Stays ≤ 3 Days | 14% | 15% | 18% | 17% | 17% | |

| Stays With Live Discharge | 24% | 23% | 15% | 16% | 16% | |

| No Gip/Chc In Last 7 Days | 77% | 66% | 64% | 73% | 74% | |

|

| ||||||

| NH RESIDENTS (%) | 32% | 38% | 25% | 24% | 26% | |

Includes all hospice stays for Medicare beneficiaries aged 65+ ending in death or discharge during the 2005–2011 study period. If an individual with multiple hospice stays receives care from more than one hospice ownership type, she is counted for each ownership type. Nursing home residents are defined as having a hospice claim at any point during a nursing home stay. Certain categories may not add to 100% due to rounding. All traits were significantly different across hospice ownership types (p<0.0001).

Table 2 illustrates the heterogeneity within the for-profit and not-for-profit categories. In stratifying the results by agency size, the findings convey the importance of considering agency size in addition to non-chain or chain status to explain differences among for-profit and, to a lesser extent, not-for-profit hospice agencies (all service use outcomes were significantly different across hospice ownership types within agency size categories (p<0.0001)). Among for-profit agencies, for instance, relative to larger agencies of the same ownership type, smaller for-profit non-chain and chain agencies generally had longer mean and median lengths-of-use; a lower proportion of stays ≤3 days; a higher proportion of stays with live discharge; and a higher proportion of decedents who do not receive any GIP or CHC level care during the last 7 days of life. Live discharge rates were especially different between the smallest and largest for-profit agencies (38% vs. 19% for for-profit non-chain agencies and 39% vs. 19% for for-profit chains). Differences existed between small and large not-for-profit non-chain and chain agencies, but they were smaller in magnitude than for for-profit agencies for length-of-use and the proportion of stays with live discharge. For instance, live discharge rates for the smallest and largest not-for-profit non-chain agencies were 20% and 14%, respectively, for non-chain not-for-profit agencies and 24% and 16%, respectively, for not-for-profit chains.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Hospice Use by Patients of FP and NFP Agencies, by Agency Size, 2005–2011

| Agencies | Patients | Mean Length Use (days) | Median Length of Use (days) | Stays ≤ 3 Days (%) | Stays with Live Discharge (%) | No GIP or CHC in Last 7 Days (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOR-PROFIT | |||||||

| FP STAND-ALONE | |||||||

| 0–50 | 851 | 49,435 | 107.2 | 35 | 10% | 38% | 89% |

| 51–200 | 769 | 232,606 | 107.3 | 31 | 11% | 30% | 87% |

| 201–400 | 249 | 179,370 | 90.3 | 23 | 14% | 23% | 80% |

| 401+ | 134 | 370,265 | 79.4 | 19 | 16% | 19% | 69% |

| FP CHAIN | |||||||

| 0–50 | 527 | 26,510 | 104.6 | 34 | 10% | 39% | 90% |

| 51–200 | 827 | 303,643 | 114.3 | 33 | 11% | 31% | 86% |

| 201–400 | 451 | 371,853 | 108.8 | 28 | 13% | 26% | 79% |

| 401+ | 260 | 910,350 | 94.4 | 18 | 17% | 19% | 55% |

| NOT-FOR-PROFIT | |||||||

| NFP STAND-ALONE | |||||||

| 0–50 | 303 | 28,821 | 70.0 | 21 | 13% | 20% | 92% |

| 51–200 | 622 | 295,869 | 69.7 | 19 | 15% | 17% | 88% |

| 201–400 | 391 | 409,502 | 64.7 | 16 | 17% | 15% | 78% |

| 401+ | 345 | 1,606,130 | 67.3 | 14 | 20% | 14% | 55% |

| NFP CHAIN | |||||||

| 0–50 | 105 | 7,871 | 76.4 | 21 | 14% | 24% | 89% |

| 51–200 | 192 | 70,570 | 71.3 | 19 | 15% | 18% | 89% |

| 201–400 | 116 | 111,975 | 68.2 | 19 | 15% | 17% | 81% |

| 401+ | 124 | 443,601 | 72.6 | 16 | 18% | 16% | 68% |

Includes all hospice stays for Medicare beneficiaries aged 65+ ending in death or discharge during 2005–2011 study period. Hospice agencies categorized into one size category for each study year (2005–2011), based on number of discharged patients in that year. Agencies may fall into different size categories in different years, as their patient populations change. All service use outcomes were significantly different i) across agency size categories within ownership type and ii) across ownership types within agency size categories (p<0.0001).

Among the largest national hospice chains, considerable variation existed in patient populations and unadjusted service use from 2011 (Table 3). The largest for-profit chains had considerably greater enrollment relative to the not-for-profit chains, with Vitas and Gentiva each serving more patients than the top 5 not-for-profit chains combined. The largest for-profit chains generally had lower proportions of patients with cancer diagnoses, higher proportions with dementia, and considerably higher proportions living in nursing homes. Substantial variation existed among the largest for-profit and not-for-profit companies. For instance, the percent of the chain’s hospice patients living in nursing homes varied from 25% at Vitas to 48% and 64% for Heartland and Aseracare, respectively. Similar variation existed in service use outcomes. Relative to the largest not-for-profit chains, the largest for-profit chains generally had longer mean and median lengths of stay and higher rates of live discharge. As with patient traits, considerable variation existed in service use outcomes among the for-profit and not-for-profit companies. For instance, the proportion of decedents who did not receive GIP or CHC level care in their last 7 days of life varied from 26%–97% among the five largest not-for-profit chains alone.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Patient Traits and Hospice Use by Patients of the Five Largest FP and NFP Chains, 2011

| Hospice Dx and Residence | Use Characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agencies | Patients | Cancer (%) | Dementia (%) | NH Residence (%) | Mean Length Use (days) | Length of Use (days) | Stays ≤3 Days (%) | Stays with Live Discharge (%) | No GIP/CHC in Last 7 Days (%) | |

| FOR-PROFIT | ||||||||||

| Largest 5 Chains | ||||||||||

| Vitas | 37 | 46,494 | 27% | 20% | 25% | 88.7 | 16 | 18% | 17% | 26% |

| Gentiva | 103 | 41,693 | 24% | 18% | 35% | 102.9 | 20 | 16% | 19% | 61% |

| Heartland | 74 | 19,541 | 22% | 22% | 48% | 106.7 | 31 | 12% | 23% | 88% |

| Amedisys | 53 | 14,075 | 22% | 17% | 34% | 99.1 | 29 | 12% | 24% | 85% |

| Aseracare | 45 | 9,973 | 18% | 22% | 64% | 98.6 | 25 | 14% | 19% | 87% |

| NOT-FOR-PROFIT | ||||||||||

| Largest 5 Chains | ||||||||||

| Hospice of the Valley | 4 | 9,086 | 29% | 4% | 14% | 95.0 | 20 | 17% | 19% | 42% |

| Providence Health and Services | 7 | 6,424 | 29% | 11% | 18% | 65.8 | 22 | 14% | 16% | 92% |

| Chapters Health Hospice | 2 | 6,407 | 30% | 16% | 22% | 87.3 | 20% | 22% | 26% | |

| Kaiser Permanente | 13 | 4,530 | 49% | 4% | 8% | 57.7 | 27 | 7% | 18% | 97% |

| Covenant Hospice | 2 | 3,734 | 30% | 13% | 30% | 96.2 | 17 | 15% | 16% | 50% |

Largest 5 chains based on number of discharged patients, 2011. Unadjusted results include all hospice stays for Medicare beneficiaries aged 65+ ending in death or discharge during the 2005–2011 study period.

Table 4 presents adjusted values for the four service use outcomes. For-profit non-chain and chain hospice agencies had longer lengths-of-use (84.5 days and 91.2 days, respectively) relative to other hospice ownership types (66.3–72.5 days), even after adjusting for patient and market characteristics. For-profit non-chain and for-profit chain agencies also had considerably higher adjusted rates of live discharge (21.0% and 20.2%, respectively), compared to other types of hospices (14.6%–15.9%). For-profit non-chain and for-profit chain agencies had lower adjusted proportions of stays of three days or less (13.9% and 14.7%, respectively), compared to other types of agencies (16.6%–17.5%). Finally, we found significant variation across ownership types in the proportion of decedents who did not receive GIP or CHC level care, but these were not consistently associated with profit status.

TABLE 4.

Adjusted Hospice Use Outcomes by Ownership Type, 2005–2011

| SERVICE USE OUTCOME | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOSPICE OWNERSHIP Type | LENGTH OF USE (DAYS) | STAYS ≤3 DAYS (%) | STAYS WITH LIVE DISCHARGE (%) | NO GIP OR CHC IN LAST 7 DAYS OF LIFE (%) |

|

FOR-PROFIT STAND ALONE |

84.5 | 13.9% | 21.0% | 75.9% |

| FOR-PROFIT CHAIN | 91.2 | 14.7% | 20.2% | 67.7% |

|

NOT-FOR-PROFIT STAND ALONE |

70.3 | 17.5% | 14.6% | 63.2% |

| NOT-FOR-PROFIT CHAIN | 72.5 | 16.6% | 15.9% | 71.6% |

| GOVERNMENT | 66.3 | 17.0% | 14.8% | 70.5% |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Includes first hospice stay only for Medicare beneficiaries aged 65+ ending in death or discharge during the 2005–2011 study period. Adjusted models focus on the associations between ownership type and each service use outcome and include as covariates: age, gender, race/ethnicity, terminal diagnosis category, HMO enrollment status, region of service use, urban/rural status, and year. Length of use modeled using ordinary least squares regression; other outcomes modeled using logistic regression. P-value associated with tests that outcomes were significantly different across all hospice ownership types.

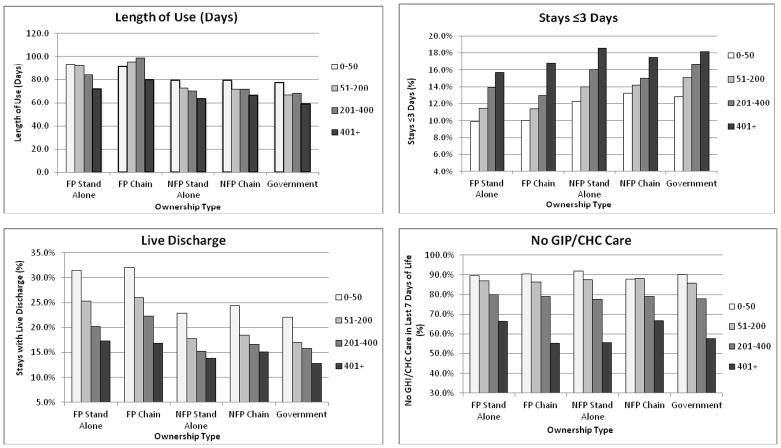

Figure 1, panels A–D show adjusted service use across ownership types, stratified by agency size categories (0–50; 51–200; 201–400; 401+). With the exception of for-profit chains, which had the highest length-of-use in 3-of-4 agency size categories, mean length-of-use generally declined as agencies grew in size. Live discharge rates generally increased as agency size decreased, and they were especially high for smaller for-profit non-chain and for-profit chain agencies. The rate of hospice stays ≤3 days generally increased as agency size increased, and for-profit non-chain and for-profit chain agencies had slightly lower rates in each agency size category. We found no clear pattern of difference in the proportion of decedents who did not receive GIP or CHC level care in their last 7 days of life, but these rates generally declined as agencies grew larger, especially when agencies served ≥400 patients.

FIGURE 1. Adjusted Hospice Use Outcomes by Ownership Type and Agency Size, 2005–2011.

Adjusted Hospice Use Outcomes by Ownership Type and Agency Size, 2005–2011. Figure 1 shows adjusted service use results across ownership types, stratified by agency size categories (0–50; 51–200; 201–400; 401+).

Includes first hospice stay only for Medicare beneficiaries aged 65+ ending in death or discharge during the 2005–2011 study period. Figures are based on adjusted regression models that include: age, gender, race/ethnicity, terminal diagnosis category, HMO enrollment status, region of service use, urban/rural status, year, and ownership status of hospice agency. Hospice agencies categorized into one of the size categories for each study year (2005–2011), based on the number of discharged patients in that particular year. Comparisons are made within size categories, across ownership types. Length of use modeled using ordinary least squares regression; other outcomes modeled using logistic regression. All outcomes were significantly different across hospice ownership types (p<0.0001). FP stands for “for-profit”; NFP stands for “not-for-profit”.

DISCUSSION

Our findings reaffirm previously identified differences in patient populations and service use between for-profit and not-for-profit hospice agencies while conveying considerable heterogeneity within the for-profit and not-for-profit hospice sectors. Similar to prior research,(2, 6, 9, 21, 22) we find that for-profit hospices have a greater focus on patients with non-cancer diagnoses and on nursing home residents than other types of agencies, and this is true for both for-profit non-chain and for-profit chain agencies. In addition, patients served by these for-profit agencies have longer lengths-of-use and higher rates of live discharge, even after adjusting for patient and market level characteristics.

Yet our results also add greater detail about the care provided by the diverse organizations operating in the U.S. hospice sector. Somewhat surprisingly, the aggregate category of “chain” appears to convey limited information on its own. Although we identify statistically significant differences, for-profit chain and non-chain agencies, in aggregate, care for roughly similar populations and have roughly similar service use outcomes to each other, and the same could be written of not-for-profit chain and non-chain agencies. This is not to say that all for-profit (or not-for-profit) hospices are alike along these dimensions. Rather, the more substantial differences we identify are found when one examines the care provided at larger and smaller agencies and across different hospice chains.

Studies of hospice ownership and the evolving hospice marketplace are most relevant to policymakers as they consider approaches to hospice oversight, quality measurement and reporting, and payment reform.(16) The differences we identify show the limitations of looking only to aggregate comparisons and the value of considering agency structure, size, and chain affiliation. In other words, ownership status alone offers a useful, but somewhat limited window through which to evaluate challenges facing the hospice industry. Our analyses take these dimensions into account to generate insights about the role of ownership in the provision of hospice.

Length-of-use and live discharge

Over the last decade, MedPAC and others have documented substantially longer lengths-of-use in for-profit relative to not-for-profit hospice agencies, additionally finding that for-profit agencies generally care for a less medically complex population.(2, 22, 23) Comparing the two most prominent hospice ownership types in our study, together serving almost three-quarters of hospice enrollees, we find that for-profit chain agencies have an adjusted mean length-of-use that is 30% higher than not-for-profit non-chain agencies. Despite these differences, it is important to note that mean length-of-use across ownership categories is well below the 180-day prognosis standard for the hospice benefit, something that reflects the continuing challenge of very short hospice stays (discussed below).

Although these results, in part, reflect market segmentation (e.g., because of distinct referral networks), the differences that remain after adjusting for patient and market traits suggest a more robust for-profit response to hospice’s per-diem payment structure, relative to not-for-profits. Although length-of-use differences are important for fiscal reasons, a related, and perhaps more troubling difference clinically is that for-profit non-chain and chain agencies had adjusted live discharge rates that were substantially higher than other types of hospice agencies. Live discharge rates were especially high for smaller for-profit non-chain and chain affiliated agencies. Disenrollment from hospice can occur for a variety of patient- and family-centered reasons, including changed patient prognoses and preferences for hospice care; however, studies have increasingly pointed to agency traits as influential.(11, 13) A related factor is that live discharge rates are especially high for individuals with very long hospice stays,(11) pointing to the potential value of considering these two factors jointly. Importantly, studies have not detailed the clinical impact of relatively high (or low) live discharge rates on patients; yet, the potentially negative impact on continuity of care from agency—rather than patient—driven discharge factors merits continued study.

Very short hospice stays

An issue of clinical importance that has received relatively little policy or regulatory attention is the persistence of very short hospice stays. Around one-in-six hospice stays are three days or less in duration, a period of time too brief to offer substantial benefits for many patients. Because the current per-diem hospice payment incentivizes longer–rather than shorter–stays, factors such as hospice eligibility policies and other barriers to referral and enrollment likely play a more prominent role. Although these factors might be expected to impact all agencies equally since they are ostensibly outside hospice agencies’ control, Not-for-profits hospices and large agencies generally had higher rates of very short stays. These trends may relate, in part, to these agencies’ referral networks. Not-for-profits agencies, for instance, are more likely than for-profits to be hospital-based,(16) potentially increasing their likelihood of receiving very late referrals from hospitals.

No CHC or GIP level care at the end of life

Hospice stays generally have the most intensive service use at their beginning, when clinicians work to develop a care plan and to stabilize patients and bring their pain and other symptoms under control, and at their end, when hospice works to support patients during the dying process. Although the current payment approach does not adjust payments across a patient’s stay, it does include two categories that reimburse brief and intensive periods of care–continuous home care and general inpatient care.

With the expectation that hospice agencies should have capacity to provide beneficiaries these intensive levels of care when needed, we examined the percent of decedents who did not receive care in either payment category in their last seven days of life. Rather than being strongly associated with profit or chain status, agency size appeared to be the factor most strongly associated with whether beneficiaries receive care in either of these categories, with the largest agencies providing this type of care to decedents at around four times the rate of the smallest agencies. Our unadjusted results also point to strong company-specific effects. Together, these results suggest either limited staffing capacity at smaller agencies and some of the larger hospice chains or different models of care for hospice provision at the end of life compared to other agencies.

Limitations

Our analyses offer a more detailed window into the role of ownership in U.S. hospice care than has been presented; however, our focus is limited to differences that can be explored using administrative data. Although our analyses adjust for patients’ terminal diagnoses and demographic traits, we do not have detailed information on comorbidities and previous service use, including hospitalizations. Nor do we have information on hospice agencies’ tenure in the marketplace across study years or on hospice companies’ strategic priorities. Some service use differences we identify highlight issues for further investigation, but they are not necessarily indicative of poor quality care. Information such as clinical records and patient and family assessments are needed to draw these types of conclusions. Although not yet available, agencies began reporting a limited set of hospice quality measures in FY 2014.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study identifies important differences across and within hospice ownership categories. Consistent with prior work, for-profit hospice generally differs from not-for-profit hospice along several key dimensions. However, our results point to the value of further refining analyses of ownership to offer a more nuanced assessment concerning the role of other structural and organizational dimensions. Such a focus will help ensure that clinicians, policymakers, and patients have the tools necessary to assess care provided by particular companies and to spur greater transparency in the hospice marketplace more generally.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the work was provided by the Hospice of the Valley Foundation to Harvard Medical School. The Foundation played no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript. Dr. Stevenson’s was supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health (NIA K01 AG038481). Dr. Keating was supported by K24CA181510 from the National Cancer Institute. Drs. Stevenson and Huskamp had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: DGS, DCG, NLK, HAH

Acquisition of subjects and/or data: DGS, HAH

Analysis and interpretation of data: DGS, DCG, NLK, HAH

Preparation of manuscript: DGS, DCG, NLK, HAH

Sponsor’s Role: HoV Foundation played no role in the design and execution of the study.

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MedPAC. Hospice Services. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (March 2014) Washington, D.C: The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2014. pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Span P. The New Old Age: Caring and Coping [Internet] [Accessed October 12, 2014];New York Times. 2014 Oct 6; Available at: http://newoldage.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/10/06/extra-scrutiny-for-hospices/

- 4.Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry CL, Cherlin EJ, et al. Hospices' enrollment policies may contribute to underuse of hospice care in the United States. Health Aff. 2012;31:2690–2698. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindrooth RC, Weisbrod BA. Do religious nonprofit and for-profit organizations respond differently to financial incentives? The hospice industry. J Health Econ. 2007;26:342–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Association of hospice agency profit status with patient diagnosis, location of care, and length of stay. JAMA. 2011;305:472–479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz KA, Ettner SL, Rosenfeld KE, et al. Cash and compassion: Profit status and the delivery of hospice services. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:507–514. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherlin EJ, Carlson MD, Herrin J, et al. Interdisciplinary staffing patterns: Do for-profit and nonprofit hospices differ? J Palliat Med. 2010;13:389–394. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandhi SO. Differences between non-profit and for-profit hospices: Patient selection and quality. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2012;12:107–127. doi: 10.1007/s10754-012-9109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canavan ME, Aldridge Carlson MD, Sipsma HL, et al. Hospice for nursing home residents: Does ownership type matter? J Palliat Med. 2013;16:1221–1226. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Plotzke M, Gozalo P, et al. A national study of live discharges from hospice. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1121–1127. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldridge MD, Schlesinger M, Barry CL, et al. National hospice survey results: For-profit status, community engagement, and service. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:500–506. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Hospice characteristics and the disenrollment of patients with cancer. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:2004–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCue MJ, Thompson JM. Operational and financial performance of publicly traded hospice companies. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1196–1206. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson MD, Barry C, Schlesinger M, et al. Quality of palliative care at U.S. hospices: Results of a national survey. Med Care. 2011;49:803–809. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822395b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson DG, Dalton JB, Grabowski DC, et al. Nearly half of all Medicare hospice enrollees received care from agencies owned by regional or national chains. Health Aff. 2015;34:30–38. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MedPAC. Hospice Services. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (March 2013) Washington, D.C: The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2013. pp. 259–284. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005 and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309:470–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, et al. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: Length of stay and bereaved family members' perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whoriskey P, Keating D. Wasington Post. May 3, 2014. Terminal neglect? How some hospices decline to treat the dying. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MedPAC. Report to Congress: Increasing the value of Medicare. Washington, D.C: MedPAC; 2006. Hospice in Medicare: Recent trends and a review of the issues; pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MedPAC. Report to Congress: New approaches in Medicare. Washington, D.C: MedPAC; 2004. Hospice in Medicare: Recent trends and a review of the issues; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MedPAC. Report to Congress: Reforming the delivery system. Washington, D.C: MedPAC; 2008. Evaluating Medicare's Hospice Benefit; pp. 201–249. [Google Scholar]