Abstract

The human transcription factor DNA replication-related element-binding factor (hDREF) is essential for the transcription of a number of housekeeping genes. The mechanisms underlying constitutively active transcription by hDREF were unclear. Here, we provide evidence that hDREF possesses small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) ligase activity and can specifically SUMOylate Mi2α, an ATP-dependent DNA helicase in the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation complex. Moreover, immunofluorescent staining and biochemical analyses showed that coexpression of hDREF and SUMO-1 resulted in dissociation of Mi2α from chromatin, whereas a SUMOylation-defective Mi2α mutant remained tightly bound to chromatin. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that Mi2α expression diminished transcription of the ribosomal protein genes, which are positively regulated by hDREF. In contrast, coexpression of hDREF and SUMO-1 suppressed the transcriptional repression by Mi2α. These data indicate that hDREF might incite transcriptional activation by SUMOylating Mi2α, resulting in the dissociation of Mi2α from the gene loci. We propose a novel mechanism for maintaining constitutively active states of a number of hDREF target genes through SUMOylation.

Keywords: gene regulation, nucleosome remodeling deacetylase (NuRD), sumoylation, transcription factor, transcription regulation, hDREF, Mi2alpha, E3 SUMO ligase

Introduction

DNA replication-related element binding factor (DREF)2 is a transcription factor that was first isolated in Drosophila (1). The Drosophila DREF (dDREF) homodimer specifically binds to the 8-bp palindromic DREF-binding element (dDRE; TATCGATA) to induce the transcription of genes involved in DNA replication and cell proliferation (2, 3). Recent work has provided clear evidence that DRE sequences are present in many Drosophila housekeeping genes, which require dDREF for their constitutive expression, whereas dDREF is dispensable for the transcription of development-related genes (4, 5). In addition, several studies have suggested a novel function for dDREF in the establishment or regulation of transcriptional insulators found in several hundred regions of the Drosophila genome (6, 7).

We previously identified hDREF as the human homolog of dDREF and determined its DNA-binding motif (hDRE; TGTCG(C/T)GA(C/T)A) (8). The hDRE sequence is similar to that of Drosophila DRE and perfectly matches the M8 motif, one of the most conserved motifs in the promoters of human genes, as determined by systematic comparative human genomics (9). In addition, hDREF was recently identified as one of the major M8-binding proteins by employing a SILAC-based quantitative proteomics approach (10). Interestingly, genes containing M8 motifs exhibited increased expression in actively proliferating cells. Accordingly, we previously demonstrated that hDREF positively regulates the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, including histone H1 and plural ribosomal protein (RP) genes (8, 11). Moreover, knockdown of hDREF resulted in impairments in cell proliferation and G1/S transition, further indicating that hDREF is a functional homolog of dDREF. Despite the importance of these functions (11), the mechanisms underlying the constitutively active transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation and the proteins that interact with DREF are currently unclear.

SUMOylation involves the covalent conjugation of an ∼100-amino acid (aa) small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) to lysine residues in the consensus TΨKXE (where Ψ is any hydrophobic residue; X is any aa residue) aa sequence on target proteins (12). Protein modification by SUMO conjugation has emerged as an important modification sufficient to alter the biochemical features or activities of proteins. A number of transcription factors are regulated by SUMO modification. SUMO-dependent transcriptional stimulation has been reported for GATA4, PAX6, and the glucocorticoid receptor (13–15). However, SUMO modification more frequently results in transcriptional repression, as is the case for c-Jun, C/EBP family members, Sp3, IκBα, KAP-1, PPARγ, and a number of other transcription factors (16–19).

SUMOylation is catalyzed by an enzymatic cascade consisting of three enzymes (12). After large SUMO precursor proteins are converted to a mature form by cleavage at the C-terminal glycine residue by SUMO protease, SUMO is attached to the heterodimeric E1 enzyme Aos1/Uba2. The activated SUMO is then transferred from the E1 enzyme to Ubc9, an E2-conjugating enzyme capable of forming a thioester intermediate between diglycine residues at the C terminus of mature SUMO proteins and the active cysteine residue of Ubc9. Ubc9 has been demonstrated to be sufficient for SUMO conjugation to substrate proteins in vitro. E3 ligases have been reported to act as adaptors between Ubc9 and SUMOylation substrate proteins; thus, the existence of an E3 ligase enhances the recognition of substrate proteins and promotes the SUMOylation conjugation reaction. Several E3 ligase enzymes have been identified, including protein inhibitor of activated STAT (PIAS) family members (20), the nuclear pore complex component RanBP2 (Nup358) (21), histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) (22), and the Polycomb group (PcG) protein Pc2 (23).

The nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation (NuRD) complex was first identified in 1998 (24–26) and contains the histone deacetylases HDAC1/2, the ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelers Mi2α/β (also known as chromodomain helicase DNA-binding proteins 3/4), RBBP4/7 (retinoblastoma-binding proteins 4/7), metastasis-associated factors (MTAs), and methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MBD2/3). Because the NuRD complex contains the dual enzymatic activities of HDAC1/2 and Mi2α/β, this complex has been proposed to mediate transcriptional repression by regulating chromosome structure (27, 28). However, recent studies have indicated that the subunit composition can vary, and thus, NuRD function may be altered by interactions between its individual complex components and other interacting molecules, including transcription factors, histone with epigenetic modifications, and methylated DNA (29–31). Despite the accumulating knowledge on the molecules that recruit NuRD to the local chromatin region, the molecular mechanism underlying the dissociation of NuRD from chromatin remains unknown.

In this study, we found that the transcription factor hDREF exhibits SUMO E3 ligase activity and specifically conjugates SUMO-1 to Lys-1971 of Mi2α. Moreover, we demonstrated that hDREF probably activates transcription by facilitating the dissociation of Mi2α from the transcribed region of hDREF target genes via SUMOylation.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 1 μg/ml streptomycin, and 29.2 μg/ml l-glutamine at 37 °C under 5% CO2. 293FT cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 0.1 mm non-essential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin, 1 μg/ml streptomycin, 29.2 μg/ml l-glutamine, and 100 μg/ml G418 at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-hDREF polyclonal antibody was described earlier (8). A rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody (clone 3F10) was purchased from Roche Applied Science, and a mouse anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (clone M2) and a rabbit anti-human MTA2 antibody (RT-16) were obtained from Sigma. A rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (catalog no. 632460) was purchased from Clontech. Mouse monoclonal anti-His6 tag antibody (ab125262), rabbit polyclonal anti-human Mi2α (CHD3) antibody (ab84528), rabbit polyclonal anti-histone H3 (trimethyl-Lys-4) antibody (ChIP grade, ab8580), rabbit polyclonal anti-histone H3 (trimethyl-Lys-9) antibody (ChIP grade, ab8898), rabbit polyclonal anti-MBD3 (ab16057) antibody, and rabbit polyclonal anti-human HDAC2 (ChIP grade, ab7029) were obtained from Abcam. A mouse monoclonal anti-RNA polymerase II (phospho-CTD) antibody (clone CTD4H8) was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. A mouse polyclonal anti-human RbAp48 antibody was purchased from MBL. Anti-rat, anti-rabbit, and anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) species-specific antibodies linked to horseradish peroxidase (NA935, NA9340, and NA9310, respectively) were obtained from GE Healthcare. Anti-rat, anti-rabbit, and anti-mouse species-specific antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (A-11007, A-11072, and A-11005) and Alexa Fluor 488 (A-11006, A-11070, and A-11001) dyes were from Life Technologies, Inc.

Plasmid Construction

The expression plasmid pcDNA3-HA-hDREF containing a full-length cDNA for hDREF was described previously (8, 32). Plasmids expressing mutant hDREF polypeptides (pcDNA3-HA-ΔhATC, W590A/W591A, and LLVL/AAAA) were described previously (32). Base substitutions (W26A, C47A, C50A, C47A/C50A, H61A, and H71A) and single aa deletions (ΔM360, ΔL401) were made by site-specific mutagenesis employing the overlap extension method using PCR with combinations of appropriate oligonucleotides. Amplified DNA fragments carrying base substitutions or deletions were digested with NheI and ApaI and then inserted between the NheI and ApaI sites of the pcDNA3-HA vector. A series of C-terminally truncated mutants of pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(1–651), -(1–551), and -(1–523) were described previously (32). For constructing pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(227–694), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 227–694, obtained by digesting pcDNA3-HA-hDREF with NcoI, creating blunt ends with Klenow fragment, and cutting with ApaI, was ligated between the blunt-ended NheI and ApaI sites of pcDNA3-HA. For constructing pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(332–694), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 332–694 was amplified by PCR, digested with NheI and XhoI, and inserted between the NheI and XhoI sites of pcDNA3-HA. For constructing pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(415–694), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 415–694, obtained by digesting pcDNA3-HA-hDREF with Asp718, creating blunt ends with Klenow fragment, and cutting with ApaI, was ligated between the blunt-ended NheI and ApaI sites of pcDNA3-HA. For constructing pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(332–524) or -(415–524), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 332–524 or 415–524, obtained by digesting pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(332–694) or pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(415–694) with BglII, creating blunt ends with Klenow fragment, and cutting with EcoRI, was ligated between the EcoRI and blunt-ended XhoI sites of pcDNA3-HA. For constructing pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(332–416), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 332–416, obtained by digesting pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(332–524) with Asp718, creating blunt ends with Klenow fragment, and cutting with EcoRI, was ligated between the EcoRI and blunt-ended XhoI sites of pcDNA3-HA. For constructing phGFP105-hDREF(332–416), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 332–416, obtained by digesting pcDNA3-HA-hDREF(332–416) with NheI, creating blunt ends with Klenow fragment, and cutting with XhoI, was ligated between the SalI and blunt-ended EcoRI sites of phGFP105-C1. For constructing phGFP105-hDREF(361–402), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 361–402, obtained by digesting phGFP105-hDREF(332–416) with PstI, was ligated between the PstI sites of phGFP105-C3. For construction of phGFP105-hDREF(332–362), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 332–362, obtained by digesting phGFP105-hDREF(332–416) with PstI and BglII, was inserted between the PstI and BglII sites of phGFP105-C1. For construction of phGFP105-hDREF(401–416), a cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 401–416, obtained by digesting phGFP105-hDREF(332–416) with PstI and BamHI, was inserted between the PstI and BamHI sites of phGFP105-C3. Expression plasmid pT2GN-FLAG-hDREF was constructed by ligating the full-length cDNA fragment with XhoI-BclI sites, obtained by PCR, with double-stranded oligonucleotides encoding FLAG epitope having compatible staggered ends for SalI into the SalI-BamHI sites of the pT2GN plasmid, a kind gift from Dr. T. Takahashi (Nagoya University) (33). Expression plasmids pECFP-SUMO-1, pECFP-SUMO-2, pECFP-SUMO-3, and pECFP-Ubc9 were described previously (19). To create expression plasmids for Myc-SUMO-1, Myc-SUMO-2, and Myc-SUMO-3, cDNAs encoding SUMO-1, SUMO-2, and SUMO-3 were amplified by PCR using plasmids pECFP-SUMO-1, pECFP-SUMO-2, and pECFP-SUMO-3 as a template, respectively. PCR products were digested with BglII and SalI and then inserted between the BglII and SalI sites of the pCMV5-Myc vector (Invitrogen). To create pGEX-4T-2-SUMO-1(GG), a cDNA fragment encoding SUMO-1 (aa 1–97) was amplified by PCR, digested with BamHI and XhoI and inserted between the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pGEX-4T-2 vector. For construction of pGEX-4T-2-Ubc9, a cDNA fragment encoding Ubc9 was amplified by PCR, digested with BamHI and XhoI, and inserted between the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pGEX-4T-2 vector. pGEX-Uba2 and pGEX-Aos1 were kindly provided by Dr. Saitoh (34). To create expression plasmids for Myc-Ubc9, Myc-PIAS1, and Myc-Pc2, full-length cDNAs for each protein were amplified by PCR using a human fetal liver MATCHMAKER library (Clontech) and inserted into the EcoRI-BglII sites of the pCMV5-Myc plasmid. Full-length cDNA for Mi2α polypeptide was cloned into pBluescript sk(−) plasmid by ligating three cDNA fragments, including a 1.6-kb NheI-MluI cDNA fragment obtained by a 5′-RACE reaction, a 3.5-kb MluI-XhoI cDNA fragment from clone 37-1, and a 0.9-kb XhoI fragment from clone 37-8 (35). The two partial cDNA clones 37-1 and 37-8 were kindly supplied by Dr. F. Aubry. First, both clone 37-1 and 37-8 (pBluescript sk(−)) DNA were digested with XhoI, and the resultant 1.5-kb (a part of cDNA) and 7.0-kb (a part of cDNA and plasmid DNA) fragments from clones 37-1 and 37-8, respectively, were ligated to obtain ΔN-Mi2α/pBluescript. A cDNA fragment corresponding to the 5′-end of Mi2α mRNA was amplified using the 5′-RACE system (Invitrogen) with a cDNA library derived from human brain mRNA (Clontech) and a pair of primers according to the manufacturer's instructions. Full-length Mi2α cDNA/pBluescript was obtained by ligating partial cDNA amplified by 5′-RACE between the EcoRV-MluI sites of ΔN-Mi2α/pBluescript. To create expression plasmid pcDNA3-HA-Mi2α(1–2000), pBluescript carrying full-length Mi2α cDNA was digested with BamHI, treated with Klenow fragment, and digested with NheI. The resulting BamHI (blunt end)-NheI DNA fragment was cloned into NheI-ApaI (blunt end) sites of the pcDNA3-HA vector. Expression plasmid harboring base substitution mutations (pcDNA3-HA-Mi2α (K1674R, K1679R, K1777R, K1876R, and K1971R)) were created as follows. Base substitutions were introduced into the 1.2-kb XbaI fragment encoding aa residues 1617–2000 of Mi2α through site-specific mutagenesis employing the overlap extension method with the appropriate oligonucleotides using pBluescript carrying full-length Mi2α cDNA as a template, and obtained XbaI fragments carrying base substitutions were swapped with the corresponding region of the pcDNA3-HA-Mi2α(1–2000). To construct His-Mi2α(1617–2000), ΔN-Mi2α/pBluescript was digested with XbaI, treated with Klenow fragment, and digested with BamHI. The resultant 1.2-kb cDNA fragment encoding aa residues 1617–2000 was inserted into the EcoRV-BamHI sites of pET47b (Novagen). PCR was performed with KOD-plus DNA polymerase (TOYOBO) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All mutations employed in this study were confirmed by DNA sequencing. All plasmids were purified using a Qiagen Plasmid Midi kit and subjected to DNA transfection.

Oligonucleotides

The primers used for hDREF cDNA amplification were as follows: WT hDREF, 5′-GGACTCGAGATGGAGAATAAAAGCCTGGAGAGC-3′ and 5′-TCCTGATCAGAAGCTGCTGTCCCTAATGCC-3′. Recognition sites for XhoI in hDREF-5′ and BclI in hDREF-3′ are underlined.

For creating base-substitutional mutants of pcDNA3-HA-hDREF, 5′-TACGGTGGGAGGTCTATATA-3′ and 5′-AGTCGAGGCTGATCAGCGAGC-3′ were used as the common forward and reverse primers, respectively. The following oligonucleotides were used as site-specific forward and reverse primers: W26A, 5′-GAGCAAGGTGGCGAAGTATTTC-3′ and 5′-GAAATACTTCGCCACCTTGCTC-3′; C47A, 5′-GAAAATCTACGCCCGCATCTGC-3′ and 5′-GCAGATGCGGGCGTAGATTTTC-3′; C50A, 5′-CTGCGCGATCGCCATGGCCCAG-3′ and 5′-CTGGGCCATGGCGATGCGGCA-3′; C47A/C50A, 5′-CTGGGCCATGGCGATGCGGGCG-3′ and 5′-GCAGATGCGGGCGTAGATTTTC-3′; H61A, 5′-CCTGTCCTACGCCCTGGAGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTCTCCAGGGCGTAGGACAGG-3′; H71A, 5′-GGAGAAGAACGCCCCCGAGGAATTC-3′ and 5′-GAATTCCTCGGGGGCGTTCTTCTCC-3′; ΔM360, 5′-AGCACGCTGGCCCTGCAGCGCCTC-3′ and 5′-GAGGCGCTGCAGGGCCAGCGTGCT-3′; ΔL401, 5′-CTGGTGGAGCTCCAGCCCTTCAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTGAAGGGCTGGAGCTCCACCAG-3′.

The oligonucleotides for the FLAG epitope were as follows: 5′-tcagCATGGACTACAAGGACCACGATGACAAAC-3′ and 5′-tcgaGCTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCCATG-3′. 5′-Overhang ends, which are compatible with staggered ends created by SalI or XhoI digestion, are indicated by lowercase letters.

The primers used in the 5′-RACE reaction for amplification of the 5′-end of Mi2α cDNA were as follows: 5′-CTTCCCGGGCTAGCATGAAGGCGGCAGACACTGTG-3′ and 5′-ATGTGGTAGGAGGAGATGCACGCGTCACAG-3′. Recognition sites for NheI and MluI are underlined.

Oligonucleotides used for base-substitutional mutants of Mi2α cDNA were as follows: K1674R, 5′-GATTTGGGCAGGAGAGAAGAT-3′ and 5′-ATCTTCTCTCCTGCCCAAATC-3′; K1679R, 5′-GAAGATGTAAGAGGTGACCGG-3′ and 5′-CCGGTCACCTCTTACATCTTC-3′; K1777R, 5′-GAGCCATTTAGAAACTGAAGCC-3′ and 5′-GGCTTCAGTTCTAAATGGCTC-3′; K1876R, 5′-AGCGACATGAGGGCGGACGTG-3′ and 5′-CACGTCCGCCCTCATCTCGCT-3′; K1971R, 5′-GTGCTTCTGAGGAAGGAGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTCTCCTTCCTCACAAGCAC-3′.

The primers used for SUMO-1, -2, and -3 cDNA amplification were as follows. 5′-CGTCGCCGTCCAGCTCGACCAG-3′, a sequence derived from ECFP cDNA, was used as the common forward primer. Reverse primers for SUMO-1, -2, and -3 were 5′-TATAGTCGACTATCTGACCAGGAGGCA-3′, 5′-TATAGTCGACTAGCCGACGAAAAGCCC-3′, and 5′-TATAGTCGACTATCCGAGGAGAAGCCC-3′, respectively. Recognition sites for SalI are underlined.

The primers used for Ubc9, PIAS1, and Pc2 (CBX4) cDNA amplification were as follows: Ubc9, 5′-ATAGAATTCATGTCGGGATCGCCCTCAG-3′ and 5′-TATAGATCTCTTCCTTCTGACGATGCCA-3′; PIAS1, 5′-ATAGAATTCATATGGCGGACAGTGCGGAA-3′ and 5′-ATAAGATCTTCAGTCCAATGAAATAATG-3′; Pc2, 5′-ATAGAATTCCCATGGAGCTGCCAGCTGTT-3′ and 5′-GCCAGATCTCTACACCGTCACGTACAC-3′. Recognition sites for EcoRI and BglII are underlined.

Oligonucleotides used for ChIP-qPCR of RPS6 and for qRT-PCR of RPS6, RPS10, RPL12, and GAPDH were described previously (11).

Yeast Two-hybrid Screening

Yeast two-hybrid screens with pretransformed human fetal brain Matchmaker cDNA library (Clontech) were performed using the full-length hDREF cDNA as bait as described previously (36).

hDREF Knockdown

Endogenous hDREF was transiently depleted by transfection with a lentiviral vector expressing shRNA against hDREF as described (11).

DNA Transfection

Plasmid DNA was transfected into cells by the calcium phosphate method as described previously (19). In the case of 293FT cells, DNA transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In Vitro Transcription/Translation

In vitro transcription and translation reactions were carried out in 50 μl of reaction mixture using the TNT-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sizes and amounts of the products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Signals were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software.

In Vitro SUMOylation Assay

Recombinant GST-SUMO-1(GG) lacking the two tandem glycine residues at the C terminus of mature SUMO-1, GST-Ubc9, GST-Uba2, GST-Aos1, and GST-hDREF were expressed in BL21 Escherichia coli (37) and purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinant His-Mi2α containing the C-terminal 384 aa (residues 1617–2000) was expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells and purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In vitro SUMOylation reactions were performed as follows. In vitro synthesized full-length 35S-Mi2α (10 μl of in vitro transcription/translation reaction) or 0.1 μg of His-Mi2α(1617–2000) was mixed with 2 μg of GST-SUMO-1(GG), 1 μg of GST-Ubc9, 0.5 μg of GST-Uba2, 0.5 μg of GST-Aos1 in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATP, and 1 mm dithiothreitol at 37 °C for 30 min. Reactions were terminated by heating the samples in Laemmli's sample buffer at 85 °C for 3 min. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and signals were detected by autoradiography or immunoblotting analysis using anti-His antibody.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Harvested cells were washed with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide, 1 mm Na3VO4, 5 mm NaF, 1 mm sodium pyrophosphate, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) for 5 min on ice prior to sonication at 4 °C and centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and appropriate antibodies were added at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml. After incubation for 3 h at 4 °C, a mixture of protein G- and protein A-Dynabeads (Invitrogen) (1:1, v/v) was added to the supernatant and rotated for 1 h at 4 °C. The Dynabeads were washed with lysis buffer supplemented with 300 mm KCl and boiled in Laemmli's sample buffer for 5 min. After brief centrifugation, the supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore), and incubated with specific antibodies as indicated. Membranes were developed using chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific), and signals were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence and Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells grown on glass coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 20 min, permeabilized in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and then blocked with 2% BSA in PBS. For digitonin permeabilization, cells on glass coverslips were permeabilized in PBS containing 20 μg/ml digitonin for 7 min at room temperature, fixed with 2% PFA in PBS, and then blocked with 2% BSA in PBS. The coverslips were incubated with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies in PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h at 25 °C. Coverslips were mounted onto a glass slide spotted with ProLong Gold or SlowFade Gold Antifade Reagents (Invitrogen), and fluorescence was then visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM 510, Zeiss).

ChIP Assays

ChIP assays were performed using 293FT cells transfected with expression plasmids based on methods described previously (11). Signals were detected by autoradiography and quantified by analyzing the image using ImageJ software. For quantitative analysis, we determined the number of PCR cycles exhibiting exponential amplification for each primer set using 2-fold serial dilutions of input sample.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from HeLa cells with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was subjected to cDNA synthesis with oligo(dT)18 primers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCRs were carried out in a mixture containing [α-32P]dCTP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and AmpliTaq Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and PCR products were separated on 6% acrylamide gels as described previously (11). Signals were detected by autoradiography and quantified by analyzing the image using ImageJ. For quantitative analysis, we determined the number of PCR cycles exhibiting exponential amplification of products for each primer set and cDNA template.

Isolation of Nuclei and Fractionation of Chromatin-bound and -unbound Proteins

Cells were harvested using cell scrapers, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and lysed by Dounce homogenization in hypotonic buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA) supplemented with 1 mm N-ethylmaleimide and protease inhibitor mixture. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min and then suspended in buffer containing 15 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mm EDTA, 0.4 m NaCl, 10% sucrose, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm N-ethylmaleimide, and protease inhibitor mixture. After incubation on ice for 30 min, chromatin-unbound (soluble) proteins were obtained as the supernatant after high speed centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in Laemmli's buffer and subjected to sonication at 4 °C prior to use as the chromatin-bound fraction. Signals were detected by autoradiography and quantified by analyzing the image using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means, and error bars correspond to S.E. unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

hDREF Interacts with Factors Involved in the SUMOylation Pathway and Is SUMOylated Both in Vitro and in Vivo

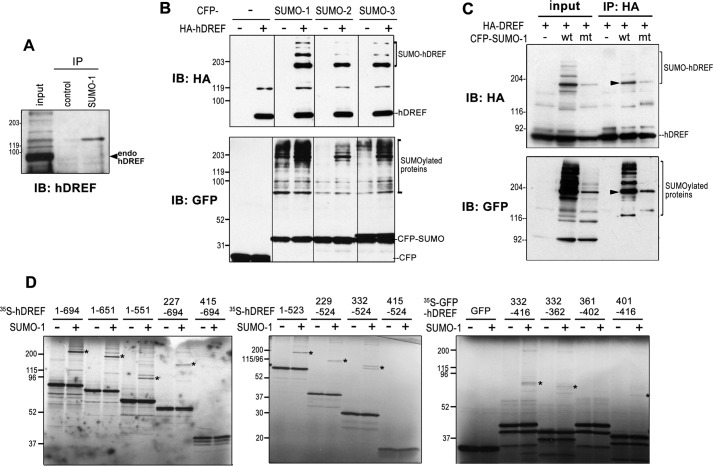

To define the molecular mechanisms by which hDREF activates transcription, we screened for hDREF-interacting proteins using the yeast two-hybrid system with a human brain cDNA library and full-length hDREF as bait. Several proteins related to the SUMO pathway, such as SUMO-1, the E2 enzyme Ubc9, and the E3 enzymes PIAS1 and Pc2 were identified as putative interaction partners in addition to Mi2α (Table 1) (36). This raised the possibility that hDREF might be modified by SUMO or have a novel function in the SUMOylation pathway. Therefore, we first investigated whether endogenous hDREF itself was a target for SUMOylation. HeLa cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-SUMO-1 antibody followed by immunoblotting analysis. Anti-hDREF antibody detected a single slower migrating band with an apparent molecular mass of 160 kDa, suggestive of SUMO-1 modification of endogenous hDREF (Fig. 1A). Next, the preference of SUMO isoforms was investigated using HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged hDREF and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-tagged SUMO-1, -2, or -3 plasmids. Western blots probed with anti-HA antibody revealed a major 180-kDa and minor higher molecular mass species in addition to the 78-kDa hDREF without SUMOylation (Fig. 1B). To confirm that the slower migrating bands were SUMO-conjugated hDREF, the conjugation-defective mutant SUMO-1-G97A (38) was coexpressed with HA-hDREF, and extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, followed by immunoblotting using anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies (Fig. 1C). Both antibodies detected a major 180 kDa band and minor higher migrating bands in samples containing WT SUMO-1, the latter of which were absent in lysates from G97A-expressing cells, indicating that these slower migrating bands corresponded to SUMOylated hDREF. Moreover, the apparent molecular mass of the slow migrating band was equivalent to that of two hDREF molecules and one SUMO protein. The combined results from the in vitro SUMOylation experiments with a series of hDREF deletion mutants (Fig. 1D) and the apparent molecular mass of endogenous hDREF conjugated with SUMO-1 suggested that an hDREF homodimer may be conjugated with a single molecule of SUMO. However, SUMOylated proteins often migrate more slowly on SDS-PAGE than expected by their estimated molecular mass; thus, more studies are required to confirm this notion.

TABLE 1.

Summary of two-hybrid screening results

| Description | Gene name | Accession no. | Protein function | No. of clones | Interaction with SUMO pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 3 | CHD3 | Q12873 | ATP-dependent DNA helicase in NuRD complex | 10 | Interacts with SUMOylated proteins |

| RAN-binding protein 9 | RANBP9 | Q96S59 | RAN-binding protein, adaptor protein | 5 | Interacts with SUMO-Ubc9 complex |

| Zinc finger prortein 451 | ZNF451 | Q9Y4E5 | Coactivator of steroid receptors | 4 | Interacts with SUMO-Ubc9 complex |

| Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 2 | TDP2 | O95551 | DNA repair enzyme | 3 | Interacts with SUMO-1 |

| Zinc fingers and homeoboxes 1 | ZHX1 | Q9UKY1 | Transcriptional repressor, DNMT3B-mediated | 3 | Conjugated with SUMO proteins |

| Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2I | UBE2I | P63279 | SUMO-conjugating enzyme, homologous to yeast Ubc9 | 1 | SUMO E2 enzyme |

| Chromobox homolog 4 | CBX4 | O00257 | Component of a PcG multiprotein PRC1-like complex | 1 | SUMO E3 enzyme |

| Protein inhibitor of activated STAT1 | PIAS1 | O75925 | SUMO E3 ligase | 1 | SUMO E3 enzyme |

FIGURE 1.

hDREF is SUMOylated. A, endogenous hDREF is conjugated with SUMO-1. Proteins in HeLa cell extract were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-SUMO-1 polyclonal antibody and subjected to immunoblotting analysis (IB) with anti-hDREF antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. B, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-hDREF and CFP-SUMO expression plasmids as indicated. HA-hDREF polypeptides with or without SUMO conjugation and SUMOylated endogenous proteins were detected by immunoblotting analysis with anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies, respectively. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. C, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-hDREF plasmid and CFP-SUMO-1 plasmids (wild-type (wt) or G97A mutant (mt) SUMO-1) as indicated. HA-hDREF polypeptides were precipitated with anti-HA antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-HA antibody (top). SUMOylated proteins coimmunoprecipitated with HA-hDREF were also detected using anti-GFP antibody (bottom). The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. Arrowheads, represent HA-hDREF with CFP-SUMO-1 conjugation. D, in vitro SUMOylation assay using a set of hDREF deletion mutants labeled with [35S]methionine. hDREF was synthesized by cell-free coupled in vitro transcription/translation in the presence of [35S]methionine and subjected to an in vitro SUMOylation reaction containing 2 μg of GST-SUMO-1(GG), 1 μg of GST-Ubc9, 0.5 μg of GST-Uba2, 0.5 μg of GST-Aos1 in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATP, and 1 mm dithiothreitol at 37 °C for 30 min. Reactions were terminated by heating the samples in Laemmli's sample buffer at 85 °C for 3 min. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and signals were detected by autoradiography. *, SUMOylated 35S-hDREF. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results.

hDREF Is a SUMO E3 Ligase

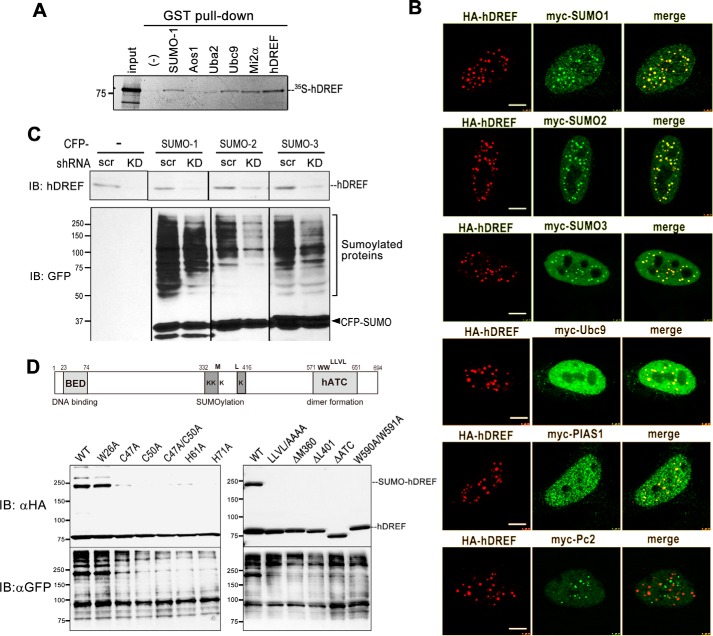

From the previous analyses, we noticed that hDREF expression enhanced the signals of SUMO-conjugated proteins (Fig. 1B). Moreover, anti-GFP antibody detected numerous SUMOylated proteins, which coimmunoprecipitated with HA-hDREF (Fig. 1C). As such, we hypothesized that hDREF is a novel transcription factor possessing SUMO ligase activity. E3 ligases are known to function as adaptors between the E2-SUMO thioester and substrate protein to facilitate SUMOylation. Thus, we examined whether hDREF physically associates with SUMO and Ubc9 (E2) by GST pull-down assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, in vitro-translated hDREF bound GST-SUMO-1 and GST-Ubc9 but was unable to bind the E1 proteins GST-Aos1 and Uba2. The physical association of hDREF with both SUMO-1 and Ubc9 E2 enzyme is compatible with our hypothesis that hDREF may be a SUMO ligase.

FIGURE 2.

hDREF increases the amount of SUMO-conjugated protein in vivo. A, 35S-labeled full-length hDREF was synthesized by a cell-free coupled in vitro transcription/translation reaction in the presence of [35S]methionine and subjected to GST pull-down using GST fusion proteins as indicated. As a positive control, GST-hDREF was used because hDREF forms a homodimer. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. B, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-hDREF plasmid and Myc-SUMO-1, Myc-SUMO-2, Myc-SUMO-3, Myc-Ubc9, Myc-PIAS1, or Myc-Pc2 plasmid as indicated. At 24 h after DNA transfection, the cells were fixed with 3.7% PFA and stained using anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies. Single confocal optical sections (n > 10) are shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. C, HeLa cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing shRNA against hDREF or scramble control. At 72 h after transduction, the cells were transfected with CFP-SUMO-1, CFP-SUMO-2, or CFP-SUMO-3 and cultured for an additional 24 h. Whole cell lysates were prepared, and protein samples (20 μg of protein) were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) using anti-hDREF antibody and anti-GFP antibody. Two independent experiments validated >85% knockdown of hDREF by shRNA. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. D, schematic representation of the hDREF structural domain and amino acid residues required for SUMO conjugation. Mutations resided in the N-terminal BED finger domain (C47A, C50A, C47A/C50A, H61A, and H71A), putative SUMOylation domain (ΔM360 and ΔL401), or the C-terminal hATC (hAT family C-terminal dimerization: pfam05699) domain (ΔATC). HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid expressing WT or mutant HA-hDREF as indicated. Whole cell lysates were prepared at 24 h after DNA transfection, and hDREF and endogenous proteins conjugated with SUMO-1 were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies, respectively. The data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

To investigate the function of hDREF in the SUMOylation further, we sought to determine the subcellular localization of hDREF, SUMO isoforms, and Ubc9. Notably, hDREF colocalized with SUMO isoforms and Ubc9 in discrete nuclear foci (Fig. 2B). The distribution and size of SUMO-hDREF foci resembled those of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) (39) or PcG nuclear bodies (40). Both specialized nuclear bodies are formed by non-covalent interactions between the SUMOylated proteins and SUMO interaction motif (SIM)-containing proteins and are considered to regulate SUMOylation in nuclei (41). Thus, to examine the relationships between hDREF-SUMO foci and PML or PcG nuclear bodies, cells expressing HA-hDREF and Myc-tagged PIAS1 or Pc2, both of which are known to be SUMO E3 ligases, were immunostained with anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies (Fig. 2B). Most of hDREF foci overlapped with PIAS1 foci, suggesting that hDREF might exist in the PML nuclear bodies. On the other hand, hDREF and Pc2 appeared to localize to mutually exclusive areas. Because a number of studies have demonstrated a crucial role of PML nuclear bodies in regulating the SUMOylation of nuclear proteins and sequestrating SUMOylated partners through its SIM sequence (39), the observed association of hDREF with PML bodies is consistent with our hypothesis that hDREF may be a SUMO ligase.

To validate this, we performed in vivo depletion assays with shRNA against hDREF (Fig. 2C) (11). To this end, HeLa cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing hDREF shRNA and then transfected with CFP-SUMO isoforms. The relative amounts of hDREF and SUMOylated proteins were then visualized on immunoblots with anti-hDREF antibody and anti-GFP antibody, respectively. As expected, hDREF knockdown markedly reduced the SUMOylation of a number of proteins, suggesting that hDREF may play a role in promoting endogenous SUMO modification. Finally, we prepared various hDREF mutants to investigate their effect on autoSUMOylation and SUMOylation of endogenous proteins other than hDREF. As shown in Fig. 2D, hDREF with mutations in the BED finger (C47A, C50A, C47A/C50A, C61A, and C71A) yielded insufficient autoSUMOylation, whereas others (LLVL/AAAA, ΔΜ360,ΔL401, ΔATC, and W590A/W591A) could not be conjugated with SUMO-1. Interestingly, expression of these SUMOylation-defective hDREF mutants markedly weakened the SUMOylation of endogenous proteins, confirming hDREF to be a SUMO ligase.

hDREF Stimulates SUMO-1 Conjugation to Mi2α

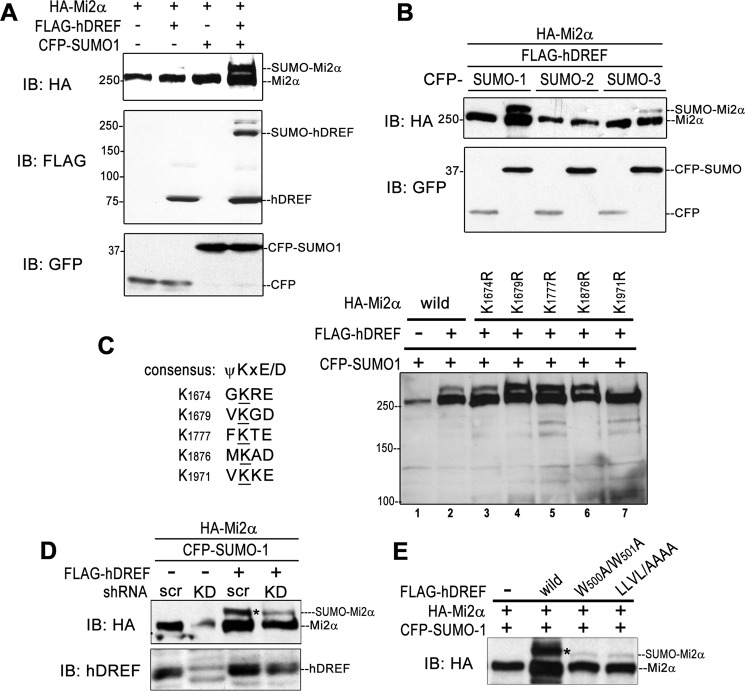

To confirm that hDREF possesses SUMO E3 ligase activity, we needed to show that hDREF can stimulate the SUMOylation of target proteins other than itself. We hypothesized that Mi2α might be a substrate of hDREF for the following reasons: 1) our two-hybrid screen revealed an interaction between hDREF and a 400-aa region at the Mi2α C terminus; 2) SUMO plot analysis showed that human Mi2α possesses five putative consensus sequences for SUMO conjugation in its C terminus (42, 43); and 3) the STRING database annotated a physical interaction between Mi2α and SUMO-1 and Ubc9. To test this hypothesis, HA-tagged Mi2α was transiently expressed with or without FLAG-hDREF and CFP-SUMO-1 in HeLa cells, and its SUMOylation status was examined by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 3A). Anti-HA antibody exhibited a strong slower migrating HA-Mi2α species with an apparent molecular mass of 290 kDa only when HA-Mi2α was co-expressed with FLAG-hDREF and CFP-SUMO-1, indicating that hDREF effectively stimulates Mi2α SUMOylation in vivo. Next, preference of SUMO isoforms was determined. As shown in Fig. 3B, HA-Mi2α polypeptide was effectively conjugated with SUMO-1 but not with SUMO-2 and SUMO-3. Finally, we determined the SUMO acceptor lysine(s) on the Mi2α polypeptide. The Mi2α C terminus contains five putative SUMOylation consensus motifs (Fig. 3C, left). Therefore, we analyzed a set of Lys → Arg mutants for their ability to act as SUMO acceptor sites (44). Significantly, the slower migrating band was nearly undetectable only in the K1971R lysate (Fig. 3C, lane 7), suggesting that Lys-1971 is the SUMO acceptor site of Mi2α. It should be noted that the amount of the wild-type Mi2α protein often tended to be significantly increased by hDREF expression (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 and 2), raising the possibility that Mi2α may be stabilized by hDREF expression.

FIGURE 3.

hDREF directs Mi2α SUMOylation in vivo. A, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-Mi2α with or without of FLAG-hDREF and CFP-SUMO-1 plasmids as indicated. Whole cell lysates were prepared at 24 h after DNA transfection, and HA-Mi2α, FLAG-hDREF, and CFP or CFP-SUMO-1 were detected by immunoblotting analysis (IB) using anti-HA, anti-FLAG, and anti-GFP antibodies, respectively. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. B, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-Mi2α and CFP-SUMO paralogs with or without FLAG-hDREF plasmid as indicated. Whole cell lysates were prepared at 24 h after DNA transfection and HA-Mi2α and CFP or CFP-SUMOs were detected by immunoblotting analysis using anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies, respectively. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. C, Mi2α is SUMOylated at Lys-1971 by hDREF. Left, alignment of putative SUMOylation sites on Mi2α. Right, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-Mi2α WT or KR mutants and CFP-SUMO-1 with or without FLAG-hDREF plasmid. At 24 h after transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared, and HA-Mi2α was detected by immunoblotting analysis using anti-HA antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. D, HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-Mi2α and CFP-SUMO-1 with or without FLAG-hDREF (shRNA-resistant) expression plasmid and plasmid expressing shRNA against hDREF mRNA (KD) or scramble shRNA plasmid as indicated. Whole cell lysates were prepared at 24 h after DNA transfection, and HA-Mi2α was detected by immunoblotting analysis using anti-HA antibody. Knockdown of endogenous hDREF and expression of shRNA-resistant hDREF were evidently detected on an immunoblot by using anti-hDREF antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. E, HeLa cells were expressed with HA-Mi2α, CFP-SUMO-1, and WT or SUMOylation-defective hDREF mutants (W500A/W501A and LLVL/AAAA) as indicated. Whole cell lysates were prepared at 24 h after DNA transfection, and Mi2α polypeptides were detected by immunoblotting analysis using anti-HA antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results.

To find further evidence that hDREF acts as an endogenous SUMO ligase for Mi2α, the effect of hDREF depletion by expressing shRNA against hDREF on HA-Mi2α SUMOylation was examined. As shown in Fig. 3D, the signal of the slower migrating SUMOylated Mi2α was significantly diminished by knocking down hDREF expression, and cotransfection of plasmid expressing shRNA-resistant mRNA for hDREF again accumulated SUMOylated Mi2α. Furthermore, expression of SUMOylation-defective hDREF mutants resulted in a marked decrease of SUMOylated Mi2α (Fig. 3E). These results established that hDREF stimulates Mi2α SUMOylation in vivo.

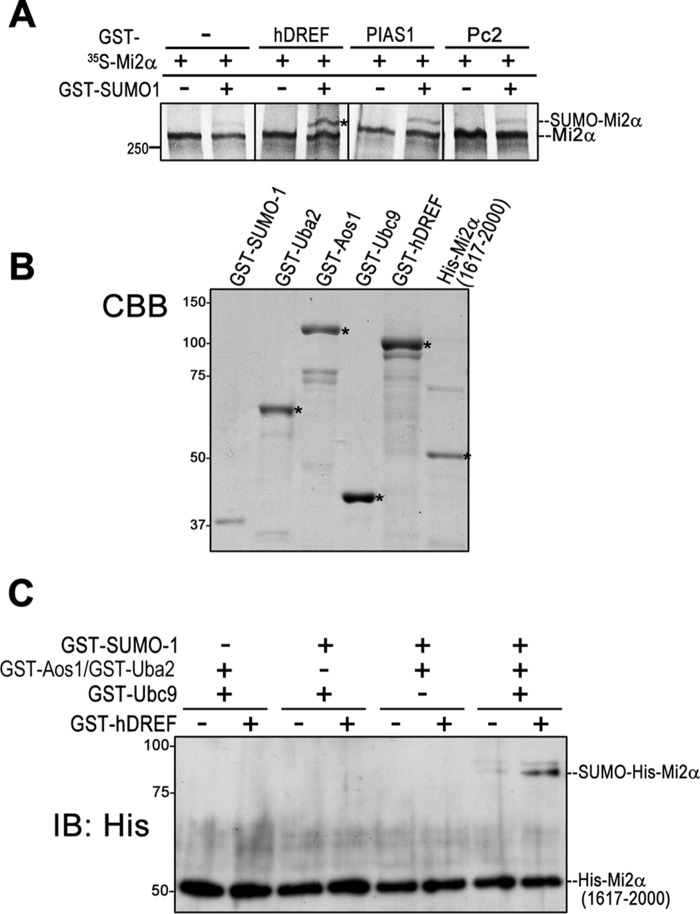

hDREF Is a SUMO Ligase

To verify that hDREF is a SUMO ligase, we next employed in vitro SUMOylation experiments where 35S-labeled 250-kDa Mi2α polypeptides were incubated in SUMOylation reaction mixture with GST-hDREF or known E3 ligases (GST-PIAS1 or GST-Pc2). As shown in Fig. 4A, the addition of GST-hDREF stimulated Mi2α SUMOylation more effectively than PIAS1 (45) and Pc2 (23). To formally prove that hDREF is a SUMO ligase, we finally performed in vitro SUMOylation experiments using purified recombinant GST-SUMO-1, GST-Aos1, GST-Uba2, GST-Ubc9, and GST-hDREF (Fig. 4B). Because E. coli cells did not successfully produce intact full-length His-Mi2α protein, purified recombinant His-tagged C-terminal Mi2α (aa 1617–2000) was used as a substrate (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 4C, an 85-kDa slower migrating form of His-Mi2α, corresponding to attachment of single GST-SUMO-1 to the C-terminal Mi2α, was detected. When either SUMO-1, E1 enzymes (Aos1/Uba2), E2 (Ubc9), or hDREF was absent, no signal of this slower migrating His-Mi2α was observed. Together, these data indicated that hDREF is a SUMO ligase that specifically conjugates SUMO-1 to Mi2α. It should also be noted that hDREF does not bind or catalyze SUMO conjugation to Mi2β, another component of the NuRD complex (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

hDREF is a SUMO E3 ligase. A, 35S-labeled full-length Mi2α was synthesized by cell-free coupled in vitro transcription/translation and subjected to in vitro SUMOylation reaction. The reaction mixture contained GST-hDREF, GST-PIAS1, or GST-Pc2 as an E3 enzyme in addition to GST-SUMO-1, GST-Uba2, GST-Aos1, and GST-Ubc9 and ATP, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Proteins were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and 35S-Mi2α polypeptide was detected by autoradiography. The data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results. B, Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining of purified recombinant proteins used in A and C. C, in vitro SUMOylation using a recombinant His-Mi2α(1617–2000). In vitro SUMOylation in the reaction mixture containing GST-SUMO-1, GST-Aos1 (E1), GST-Uba2 (E1), GST-Ubc9 (E2), GST-hDREF, and His-Mi2α(1617–2000), as indicated, was performed. Proteins were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and His-Mi2α polypeptide was detected by immunoblotting analysis (IB) using anti-His antibody. The data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

Binding of hDREF to Mi2a Depends on the Presence of SUMO-1

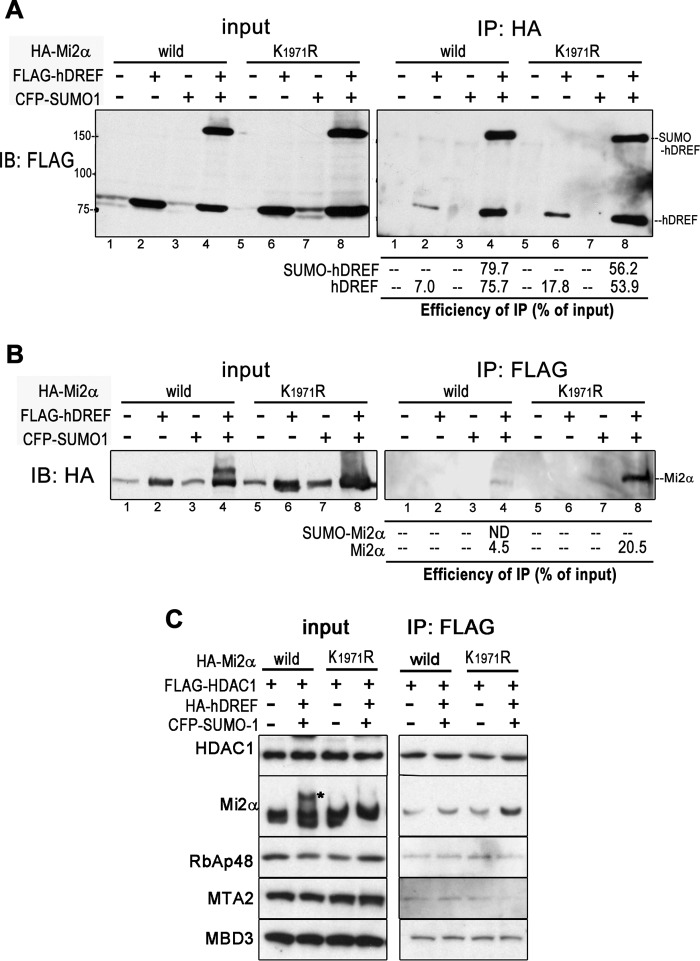

To determine the trigger for Mi2α SUMOylation by hDREF, we first examined whether their physical interaction was modulated by SUMOylation. Interactions between hDREF and Mi2α were investigated by immunoprecipitation using 293FT cells transfected with either WT or K1971R HA-Mi2α in various combinations with FLAG-hDREF and CFP-SUMO-1. Interestingly, both WT and K1971R Mi2α immunoprecipitated a considerable amount of hDREF with or without SUMOylation in the presence of SUMO-1 expression (Fig. 5A, lanes 4 and 8); however, a small amount of hDREF was pulled down in the absence of SUMO-1 expression (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 6). Immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody similarly showed an association between hDREF and Mi2α dependent on SUMO-1 expression (Fig. 5B, lane 4 and 8). Nevertheless, hDREF did pull down WT but not SUMOylated Mi2α (Fig. 5B, lane 4). Surprisingly, hDREF immunoprecipitated with K1971R Mi2α far more effectively than with WT (Fig. 5B, lane 8). Altogether, it is likely that hDREF may bind to non-SUMOylated Mi2α with higher affinity than to SUMOylated Mi2α, and their affinity may be enhanced in the presence of SUMO-1.

FIGURE 5.

SUMO-1 enhances the association between hDREF and Mi2α. A, 293FT cells were cotransfected with HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R mutant) with or without CFP-SUMO-1 and FLAG-hDREF plasmids as indicated. At 24 h after DNA transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-HA antibody. hDREF and its SUMOylated form co-immunoprecipitated with Mi2α were detected by immunoblotting analysis (IB) using anti-FLAG antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. B, 293FT cells were cotransfected with HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R mutant) with and without CFP-SUMO-1 and FLAG-hDREF plasmids as indicated. At 24 h after DNA transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody. Mi2α and its SUMOylated form in the immunoprecipitated material were detected by immunoblotting analysis using anti-HA antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. C, 293FT cells were transfected with FLAG-HDAC1 and HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R mutant) with or without CFP-SUMO-1 and HA-hDREF plasmids as indicated. At 24 h after DNA transfection, cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody. Components of NuRD complex (HDAC1, Mi2α, RbAp48, MTA2, and MBD3) in the immunoprecipitated samples were detected with anti-FLAG, anti-HA antibodies, and specific antibodies against RbAp48, MTA2, and MBD3, respectively. The data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

Mi2α is a component of the NuRD chromatin-remodeling complex (46, 47); therefore, we tested whether Mi2α SUMOylation alters NuRD complex formation. To this end, we transfected FLAG-HDAC1 and HA-Mi2α plasmids with or without HA-hDREF and CFP-SUMO-1 plasmids into 293FT cells and examined the association of Mi2α with NuRD complex by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody. As shown in Fig. 5C, WT and K1971R Mi2α were similarly co-immunoprecipitated with HA-HDAC2 and other members of the NuRD complex, including RbAp48, MTA2, and MBD3, regardless of hDREF and SUMO-1 expression. These data indicate that SUMOylation of Mi2α does not affect NuRD complex formation.

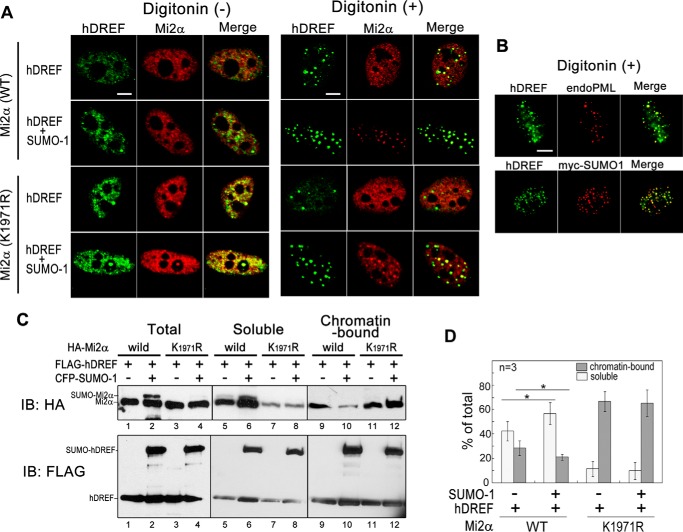

hDREF Dissociates Mi2α from Chromatin in a SUMO-1-dependent Manner

To assess the role of Mi2α SUMOylation, we investigated the effect of hDREF/SUMO-1 coexpression on the subcellular localization of Mi2α. FLAG-hDREF and HA-WT or HA-K1971R Mi2α with or without Myc-SUMO-1 were expressed in HeLa cells, and signals for hDREF and Mi2α were immunofluorescently detected (Fig. 6A, left). Notably, without SUMO-1 expression, hDREF and HA-WT or -K1971R Mi2α were distributed in the nucleoplasm, and significant portions of hDREF and Mi2α were colocalized on diffused foci. However, when Myc-SUMO-1 was coexpressed, hDREF signals were observed as clear foci and colocalized with both WT and K1971R Mi2α, corroborating that the association between hDREF and Mi2α may depend on the presence of SUMO-1. Next, we examined hDREF and Mi2α signals after treatment with digitonin, a detergent that effectively releases the nuclear contents (Fig. 6A, right). Under these conditions, hDREF was detected as strong foci, and the number of foci increased by SUMO-1 expression. Staining of cells simultaneously expressing FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α, and Myc-SUMO-1 using anti-PML, anti-FLAG, and anti-Myc antibodies showed colocalization of hDREF with endogenous PML and Myc-SUMO-1 proteins in these foci, indicating that they corresponded to the PML bodies and that hDREF and Mi2α within the PML nuclear bodies are resistant to digitonin treatment (Fig. 6B). The distribution pattern of WT Mi2α without SUMO-1 expression in digitonin-treated cells was similar to that in non-treated cells. Surprisingly, digitonin treatment of SUMO-1-expressing cells led to the disappearance of the diffuse WT Mi2α signals from the nucleoplasm, whereas the Mi2α signals within the PML nuclear bodies remained with hDREF. In contrast, K1971R Mi2α in the nucleoplasm as well as within the PML nuclear bodies was not diminished by digitonin treatment regardless of the presence or absence of SUMO-1. These results suggested that the solubility of Mi2α from nucleoplasm may be increased by SUMO modification. Therefore, we speculated that SUMOylation at Lys-1971 of Mi2α may weaken the binding affinity of Mi2α to global chromatin. To confirm this possibility, we carried out biochemical experiments to determine whether the chromatin-binding activities of Mi2α and hDREF were altered by SUMO modification (Fig. 6, C and D). To this end, we prepared soluble and chromatin-bound protein fractions from the cell lysates of 293FT cells expressing WT or K1971R Mi2α and hDREF with or without SUMO-1. Both fractions were subjected to Western analysis using anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. Interestingly, WT Mi2α was enriched in the soluble fraction (Fig. 6C, lanes 5 and 6), and the amount of chromatin-bound Mi2α was significantly reduced by coexpression of SUMO-1 (Fig. 6C, lane 10). Notably, SUMOylated Mi2α was detected only in the soluble fraction (Fig. 6C, lane 6). In contrast, a larger portion of K1971R Mi2α was detected in the chromatin-bound fraction regardless of SUMO-1 expression (Fig. 6C, lanes 11 and 12). In summary, the biochemical data were consistent with those of immunofluorescence analysis; thus, we concluded that Mi2α SUMOylation may cause Mi2α dissociation from global chromatin.

FIGURE 6.

SUMOylation by hDREF promotes release of Mi2α from chromatin. A, HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R mutant), or Myc-SUMO-1 as indicated. At 24 h after DNA transfection, cells were treated with or without 40 μm digitonin for 6 min at 20 °C, fixed with 2% PFA, and stained with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies followed by Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibodies. In the case of no treatment with digitonin, cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 after fixation. Signals of FLAG-hDREF and HA-Mi2α were shown in confocal images using Zeiss LSM 510 microscope. Scale bars, 5 μm. The images are representative of cells (n > 50) examined in three independent experiments. B, HeLa cells simultaneously expressing FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α (WT), and Myc-SUMO-1 were treated with 40 μm digitonin for 7 min at 20 °C, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and immunostained with anti-FLAG and anti-PML antibodies (top) or with anti-FLAG and anti-Myc antibodies (bottom) as indicated. Confocal images of signals were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope. Scale bars, 5 μm. The images are representative of cells (n > 50) examined in three independent experiments. C, 293FT cells were transfected with FLAG-hDREF or HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R mutant) with or without CFP-SUMO-1 plasmid as indicated. At 24 h after DNA transfection, soluble and chromatin-bound fractions were prepared by biochemical fractionation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” hDREF and Mi2α in each fraction were detected by immunoblotting analysis (IB) using anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments. D, signals of Mi2α in the soluble and chromatin-bound fractions were quantified by densitometry scanning of immunoblots. Graphs show the percentage of Mi2α in the soluble fraction and in the chromatin-bound fraction recovered from total cell lysates. Error bars, S.E. *, p < 0.05, n = 3.

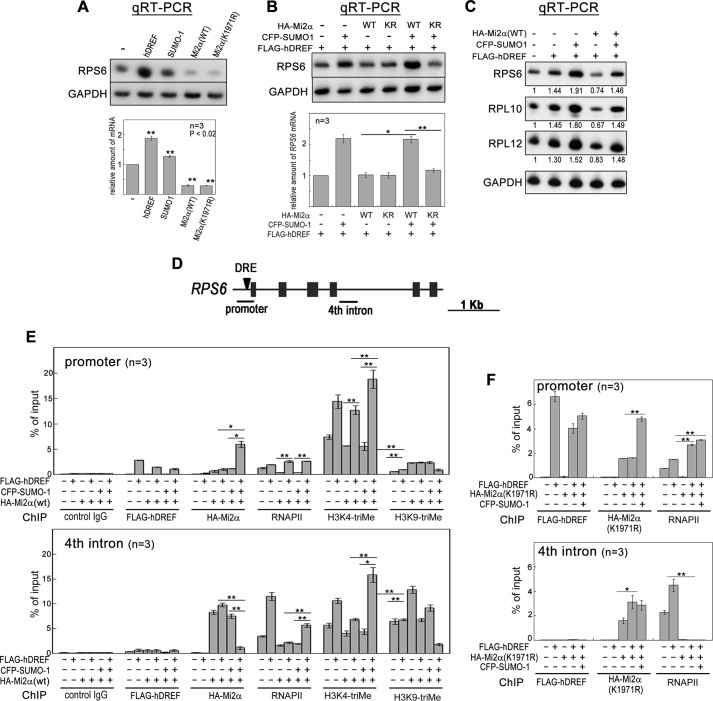

hDREF Stimulates Transcription of the hDREF Target Genes by Dissociating Mi2α from Their Gene Body via SUMOylation

Finally, we examined the effect of Mi2α SUMOylation on the transcriptional activity of hDREF target genes. We first investigated transcription of the RPS6 gene containing an hDRE 51 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS). Sole expression of hDREF, SUMO-1, and WT Mi2α resulted in a 110% increase, a 27% increase, and a 70% decrease in RPS6 mRNA, respectively (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, sole expression of K1971R Mi2α also reduced RPS6 mRNA to the same extent as WT, suggesting that SUMOylation-defective Mi2α may retain transcriptional repressive activity. Next, we investigated whether Mi2α can repress RPS6 transcription upon stimulation by hDREF expression (Fig. 7B). Without SUMO-1 expression, WT or K1971R Mi2α did not apparently reduce RPS6 transcription, suggesting that Mi2α could not substantially repress RPS6 hDREF-stimulated transcription. Additionally, coexpression of SUMO-1 with WT Mi2α significantly increased RPS6 gene transcription in the presence of hDREF. Surprisingly, co-expression of SUMO-1 with K1971R Mi2α did not enhance RPS6 transcription in the cells expressing hDREF. These results indicate that hDREF may suppress the transcriptional repressive activity of Mi2α by SUMOylation at Lys-1971. Supportive evidence was also obtained by qRT-PCR analysis of the hDREF target genes RPL10 and RPL12 (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

hDREF and SUMO-1 coexpression overcomes transcriptional repression by Mi2α. A, HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid expressing FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R), or CFP-SUMO-1 as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, total RNA was extracted, and qRT-PCR was performed for RPS6 and GAPDH. The intensity of individual bands was quantified and expressed relative to the control (no transfection). Amounts of RPS6 mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH as an internal control. Data are the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E. **, p < 0.02; n = 3. B, HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R), or CFP-SUMO-1 in the indicated combinations. At 48 h after transfection, total RNA was extracted, and qRT-PCR was performed for RPS6 and GAPDH. Amounts of RPS6 mRNA were normalized by those of GAPDH as an internal control. Data are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.02; n = 3. C, HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α (WT or K1971R), and CFP-SUMO-1 as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, total RNA was extracted, and qRT-PCR was performed for RPS6, RPL10, RPL12, and GAPDH. Amounts of mRNA of RPS6, RPL10, and RPL12 were normalized by those of GAPDH as an internal control. Data are expressed as the average value relative to a no transfection control. n = 3. D, schematic illustration of the RPS6 gene. Arrowhead, a hDREF binding site. Solid bars, the region amplified by PCR in ChIP analysis. E, 293FT cells were transfected with FLAG-hDREF, HA-Mi2α, and CFP-SUMO-1 as indicated. At 36 h after transfection, cells were cross-linked with 1.1% formaldehyde for 5 min, lysed, and sonicated. After centrifugation, the cleared supernatant containing chromatin was subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies (control IgG, anti-FLAG, anti-HA, anti-RNA polymerase II (phospho-CTD), anti-histone H3 Lys-4-trimethyl, and anti-histone H3 Lys-9-trimethyl). PCR was quantitatively performed in the reaction mixture containing 32P-dCTP using genomic DNA from the input extract and DNA recovered from the immunoprecipitates as indicated. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 6% acrylamide gels and detected by autoradiography. The intensity of individual bands was quantified and expressed as a percentage of input. Data are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.02). F, ChIP assays were performed using antibodies as described. Instead of WT Mi2α, SUMOylation-defective K1971R mutant was expressed in 293FT cells. Data are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.02).

We analyzed the binding status of hDREF and Mi2α, phosphorylated RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) recruitment, and histone modifications in the proximal and distal regions of the RPS6 gene promoter by ChIP analysis (Fig. 7D). Enriched hDREF signals at the promoter showed that hDREF was evidently bound to the DRE 51 bp upstream of the TSS regardless of the simultaneous expression of Mi2α or SUMO-1. Interestingly, a significant amount of RNAPII accumulated at the promoter region dependent on hDREF occupancy, suggesting that hDREF stimulates recruitment of RNAPII at the promoter. Surprisingly, Mi2α was also extremely concentrated at the promoter region when hDREF and SUMO-1 were coexpressed (Fig. 7E, top). The accumulation of Mi2α was consistent with the immunoprecipitation data indicating that affinity between Mi2α and hDREF was enhanced by SUMO-1 expression. Interestingly, there was an overall inverse correlation between the binding status of Mi2α and RNAPII at a 2-kb region downstream from the TSS (corresponding to the fourth intron) (Fig. 7E, bottom). Mi2α expressed solely or together with hDREF or SUMO-1 occupied the fourth intron, but Mi2α signal disappeared when expressed simultaneously with hDREF and SUMO-1. RNAPII signal in the fourth intron, presumably reflecting active transcriptional elongation, was decreased when Mi2α occupied the region but was markedly increased when Mi2α was dissociated from the region. Furthermore, the pattern of histone H3 K4 trimethylation, a marker of active transcription, was mostly similar to that of RNAPII. Moreover, trimethylated histone H3 Lys-9, a marker of inactive transcription, exhibited trimethylation patterns inverse to those of H3 Lys-4. Together, the binding status of Mi2α and RNAPII seems to be mutually exclusive; thus, the absence of Mi2α and the presence of RNAPII in the gene body may be required for active RPS6 transcription. Finally, we performed ChIP with cells expressing K1971R Mi2α (Fig. 7F). Expectedly, SUMOylation-defective Mi2α bound in the fourth intron, even with hDREF and SUMO-1 coexpression. Under this condition, RNAPII was hardly detected in that location. Collectively, these results strongly suggested that hDREF may stimulate RPS6 expression by Mi2α SUMOylation that causes the release Mi2α from the gene body of RPS6.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that the sequence-specific transcription factor hDREF possesses SUMO ligase activity and stimulates transcription of target genes via direct SUMO ligation to Mi2α, an ATP-dependent nucleosome-remodeling enzyme in the NuRD complex. We propose a novel mechanism by which the sequence-specific transcription factor cancels Mi2α-mediated transcriptional repression. Several studies have revealed that the NuRD complex is recruited to chromatin through protein-DNA interactions between MBD2 and methylated DNA and protein-protein interactions between Mi2α/β and histone H3 (27, 28) and between RBBP7/4 and histone H4. In addition, considerable evidence indicates that the NuRD can also be recruited to focal chromatin regions by specific interactions with transcription factors or corepressors (48–50). However, it remains unclear how the repressive NuRD complex dissociates from chromatin when necessary. Thus, our findings provide new insights into SUMOylation-dependent dissociation of the NuRD complex from chromatin.

Immunofluorescence and biochemical analyses clearly showed that hDREF and SUMO-1 coexpression resulted in an increased amount of unbound Mi2α, whereas the SUMOylation-defective K1971R mutant tightly bound to chromatin (Fig. 6, A and C). This result indicated that Mi2α SUMOylation by hDREF is sufficient to dissociate Mi2α from chromatin, directly inhibit Mi2α binding to chromatin, or prevent the incorporation of Mi2α into the NuRD complex. However, immunoprecipitation revealed that Mi2α could associate with the NuRD complex with or without SUMO-1 to a similar extent, suggesting that Mi2α SUMOylation does not affect NuRD complex formation. Thus, it is more likely that the chromatin binding affinity of Mi2α in the NuRD complex (Mi2α-NuRD) may be weakened as a result of Mi2α SUMOylation.

Using ChIP analysis, we examined the binding of Mi2α to the hDREF target gene RPS6, and we observed that Mi2α distribution patterns at the promoter region and the gene body differed depending on the combination of hDREF and SUMO-1 expression. When Mi2α was expressed alone or with hDREF or SUMO-1, Mi2α signal at the promoter region was relatively weak, whereas a more intense signal was detected in the gene body. Inversely, Mi2α was enriched at the promoter and completely absent in the gene body upon coexpression of hDREF and SUMO-1. In contrast, RNAPII and histone modification signals for active gene transcription disappeared with Mi2α expression and were enhanced by the simultaneous expression of hDREF and SUMO-1. Thus, it is evident that signals for active transcription emerged in gene body concurrent with the absence of Mi2α. Thus, the absence of Mi2α (or Mi2α-NuRD) in the gene body, rather than at the promoter, may be important to incite transcription elongation, and RNAPII stalled at the promoter-proximal region may be released, dependent upon the simultaneous expression of hDREF and SUMO-1. This led us to question how Mi2α is dissociated from the gene body in the presence of hDREF and SUMO-1. We developed a model based upon the following lines of evidence: 1) the interaction between hDREF and Mi2α was enhanced in the presence of SUMO-1 (Fig. 5, A and B); 2) Mi2α exhibited a similar affinity to both SUMOylated hDREF and non-SUMOylated hDREF (Fig. 5A); 3) SUMOylation-defective K1971R Mi2α was coimmunoprecipitated with hDREF much more effectively than WT Mi2α (Fig. 5B); 4) even in the presence of hDREF and SUMO-1, K1971R Mi2α existed in the gene body, whereas WT Mi2α disappeared in such situation (Fig. 7, E and F). Thus, we presumed that Mi2α may be locally recruited to the promoter region through a direct protein-protein interaction with SUMOylated hDREF, conjugated with SUMO-1 by hDREF, and subsequently dissociated from chromatin, thereby limiting Mi2α occupancy at the distal promoter region. To confirm this model, further studies on binding and dissociation kinetics between hDREF and Mi2α with or without SUMO modification using an in vitro reconstitution system should be performed. Moreover, it would be of great interest to elucidate the role of PML nuclear bodies, to which a large part of hDREF and Mi2α colocalize dependent on SUMO-1 expression. PML nuclear bodies are proposed to regulate a wide variety of processes through sequestration of PML-interacting proteins via its SUMO-SIM interaction; therefore, we speculate that hDREF may tether unbound Mi2α to PML nuclear bodies through its SUMOylation in order to maintain active transcription. To verify this possibility, future studies are necessary to clarify molecular interactions among hDREF, Mi2α, and PML.

We cannot exclude the possibility that hDREF stimulates transcription by tethering Mi2α-NuRD to the promoter region and switching Mi2α-NuRD function from transcription repression to activation through Mi2α. Several reports support this possibility. For example, the Mi2α-NuRD complex enhances transcription by acting as a c-Myb coactivator (51). More recently, the IKAROS transcription factor has been shown to stimulate transcription elongation in a hematopoietic cell lineage by concurrently recruiting NuRD complex (49) and the positive transcription elongation factor β (P-TEFβ) (49). Moreover, Shimbo et al. demonstrated that the MBD3-containing NuRD complex occupies CpG-rich promoters marked by histone H3 Lys-4 trimethylation; thus, the MBD3-NuRD complex may play multiple roles in fine-tuning the expression of both active and silent genes (31). These findings suggest that the NuRD complex acts as transcription activator depending on its interacting partners. Further studies to analyze the characteristics of SUMOylated Mi2α-NuRD are required to fully understand its molecular functions. For this purpose, reconstitution with a SUMOylation mimic mutant of Mi2α may be of use.

Liu et al. (52) showed that SUMO-1 occupies the proximal promoter regions of numerous human housekeeping genes. They also demonstrated that ribosomal protein genes, which are most actively and constitutively expressed, are remarkably enriched with SUMO-1 at the chromatin surrounding the TSSs and that depletion of SUMO-1 resulted in down-regulation of these genes. Surprisingly, six ribosomal protein genes in their list (RPL5, RPL7A, RPL10A, RPL17, RPL26, and RPS16) commonly contain hDRE at the −41 to −67 positions from their TSSs (11). Thus, it is possible that SUMO-1 enrichment at the proximal promoter regions of these genes may reflect that the SUMOylated hDREF bound to the hDREs exists in the proximal promoter regions and that hDREF may be important for constitutively active transcription of a set of housekeeping genes. Indeed, most dDREF-binding motifs localize proximal to the TSSs of Drosophila housekeeping genes, and dDRE motifs are required and sufficient for enhancer function of housekeeping genes (4). Further research on the distribution of Mi2α, hDREF, SUMO-1, and RNAPII over a wide range of chromatin using ChIP-sequencing and RNA-sequencing analyses will be helpful to reveal whether or not SUMO ligase activity of hDREF is generally involved in active transcription of hDRE-containing housekeeping genes.

Additionally, we speculate that the position of hDRE from the TSS might be critical for hDREF function. The hDRE-binding position of candidate hDREF target genes exhibited a narrow peak at 62 bp upstream of the TSS (9). Considering that RNAPII was definitely recruited to the promoter and that histone modifications reflecting active transcription were concentrated at the promoter-proximal region when hDREF was bound to the hDRE (Fig. 7E) with or without the presence of SUMO-1 and Mi2α, hDREF may solely promote epigenetic changes at the promoter region to facilitate transcription initiation. Our preliminary result obtained by immunoprecipitation using anti-hDREF antibody showed specific interaction between hDREF and CBP or TFIIF. CBP is a well characterized transcriptional coactivator with histone acetyltransferase activity (53). TFIIF is associated with RNAPII and assists RNAPII preinitiation complex formation as well as direct elongation initiation complex formation (54, 55). Future detailed analysis of the interaction between hDREF and histone acetyltransferase or general transcription factors is needed.

In summary, we provided evidence that hDREF acts as a SUMO ligase and may cancel transcription repression by the Mi2α-NuRD complex through specific SUMO conjugation on Mi2α. We speculate that hDREF is kept transcriptionally active in a set of housekeeping genes carrying the hDRE. Further research will be necessary to identify other substrates of hDREF to clarify the possible molecular mechanism for keeping constitutively active states of a number of hDREF target genes.

Author Contributions

F. H. designed the study. D. Y., T. M., and F. H. performed the experiments. F. H. analyzed the data, prepared the figures for publication, and wrote the manuscript. T. O. contributed ideas for the research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. H. Saito (Kumamoto University) for providing plasmids containing GST-Aos1, -Uba2, and -Ubc9. We also thank Dr. H. Miyoshi (RIKEN, BRC) for providing lentiviral vector.

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant KAKENHI 20570188 (to F. H.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- DREF

- DRE-binding factor

- dDREF and hDREF

- Drosophila and human DREF, respectively

- DRE

- DNA replication-related element

- dDRE and hDRE

- Drosophila and human DRE, respectively

- aa

- amino acid(s)

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- NuRD

- nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation

- PFA

- paraformaldehyde

- PML

- promyelocytic leukemia

- qRT

- quantitative reverse transcription

- RNAPII

- RNA polymerase II

- RP

- ribosomal protein

- SIM

- SUMO interaction motif

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-related modifier

- TSS

- transcription start site

- PIAS

- protein inhibitor of activated STAT

- PcG

- Polycomb group.

References

- 1. Hirose F., Yamaguchi M., Kuroda K., Omori A., Hachiya T., Ikeda M., Nishimoto Y., and Matsukage A. (1996) Isolation and characterization of cDNA for DREF, a promoter-activating factor for Drosophila DNA replication-related genes. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 3930–3937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matsukage A., Hirose F., Yoo M. A., and Yamaguchi M. (2008) The DRE/DREF transcriptional regulatory system: a master key for cell proliferation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1779, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hirose F., Ohshima N., Shiraki M., Inoue Y. H., Taguchi O., Nishi Y., Matsukage A., and Yamaguchi M. (2001) Ectopic expression of DREF induces DNA synthesis, apoptosis, and unusual morphogenesis in the Drosophila eye imaginal disc: possible interaction with Polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7231–7242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zabidi M. A., Arnold C. D., Schernhuber K., Pagani M., Rath M., Frank O., and Stark A. (2015) Enhancer-core-promoter specificity separates developmental and housekeeping gene regulation. Nature 518, 556–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jasper H., Benes V., Atzberger A., Sauer S., Ansorge W., and Bohmann D. (2002) A genomic switch at the transition from cell proliferation to terminal differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Dev. Cell 3, 511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lhoumaud P., Hennion M., Gamot A., Cuddapah S., Queille S., Liang J., Micas G., Morillon P., Urbach S., Bouchez O., Severac D., Emberly E., Zhao K., and Cuvier O. (2014) Insulators recruit histone methyltransferase dMes4 to regulate chromatin of flanking genes. EMBO J. 33, 1599–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hart C. M., Cuvier O., and Laemmli U. K. (1999) Evidence for an antagonistic relationship between the boundary element-associated factor BEAF and the transcription factor DREF. Chromosoma 108, 375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohshima N., Takahashi M., and Hirose F. (2003) Identification of a human homologue of the DREF transcription factor with a potential role in regulation of the histone H1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22928–22938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie X., Lu J., Kulbokas E. J., Golub T. R., Mootha V., Lindblad-Toh K., Lander E. S., and Kellis M. (2005) Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3′ UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature 434, 338–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trung N. T., Engelke R., and Mittler G. (2014) SILAC-based quantitative proteomics approach to identify transcription factors interacting with a novel cis-regulatory element. J. Proteomics Bioinform. 10.4172/jpb.1000306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamashita D., Sano Y., Adachi Y., Okamoto Y., Osada H., Takahashi T., Yamaguchi T., Osumi T., and Hirose F. (2007) hDREF regulates cell proliferation and expression of ribosomal protein genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 2003–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gareau J. R., and Lima C. D. (2010) The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yan Q., Gong L., Deng M., Zhang L., Sun S., Liu J., Ma H., Yuan D., Chen P. C., Hu X., Liu J., Qin J., Xiao L., Huang X. Q., Zhang J., and Li D. W. (2010) Sumoylation activates the transcriptional activity of Pax-6, an important transcription factor for eye and brain development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21034–21039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Le Drean Y., Mincheneau N., Le Goff P., and Michel D. (2002) Potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activity by sumoylation. Endocrinology 143, 3482–3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang J., Feng X. H., and Schwartz R. J. (2004) SUMO-1 modification activated GATA4-dependent cardiogenic gene activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49091–49098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bossis G., Malnou C. E., Farras R., Andermarcher E., Hipskind R., Rodriguez M., Schmidt D., Muller S., Jariel-Encontre I., and Piechaczyk M. (2005) Down-regulation of c-Fos/c-Jun AP-1 dimer activity by sumoylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6964–6979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang T. T., Wuerzberger-Davis S. M., Wu Z. H., and Miyamoto S. (2003) Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell 115, 565–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ivanov A. V., Peng H., Yurchenko V., Yap K. L., Negorev D. G., Schultz D. C., Psulkowski E., Fredericks W. J., White D. E., Maul G. G., Sadofsky M. J., Zhou M. M., and Rauscher F. J. 3rd (2007) PHD domain-mediated E3 ligase activity directs intramolecular sumoylation of an adjacent bromodomain required for gene silencing. Mol. Cell 28, 823–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamashita D., Yamaguchi T., Shimizu M., Nakata N., Hirose F., and Osumi T. (2004) The transactivating function of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is negatively regulated by SUMO conjugation in the amino-terminal domain. Genes Cells 9, 1017–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Galanty Y., Belotserkovskaya R., Coates J., Polo S., Miller K. M., and Jackson S. P. (2009) Mammalian SUMO E3-ligases PIAS1 and PIAS4 promote responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 462, 935–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Werner A., Flotho A., and Melchior F. (2012) The RanBP2/RanGAP1*SUMO-1/Ubc9 complex is a multisubunit SUMO E3 ligase. Mol. Cell 46, 287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang Y., Tse A. K., Li P., Ma Q., Xiang S., Nicosia S. V., Seto E., Zhang X., and Bai W. (2011) Inhibition of androgen receptor activity by histone deacetylase 4 through receptor SUMOylation. Oncogene 30, 2207–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kagey M. H., Melhuish T. A., and Wotton D. (2003) The polycomb protein Pc2 is a SUMO E3. Cell 113, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tong J. K., Hassig C. A., Schnitzler G. R., Kingston R. E., and Schreiber S. L. (1998) Chromatin deacetylation by an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling complex. Nature 395, 917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang Y., LeRoy G., Seelig H. P., Lane W. S., and Reinberg D. (1998) The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell 95, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xue Y., Wong J., Moreno G. T., Young M. K., Côté J., and Wang W. (1998) NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol. Cell 2, 851–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Allen H. F., Wade P. A., and Kutateladze T. G. (2013) The NuRD architecture. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3513–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becker P. B., and Workman J. L. (2013) Nucleosome remodeling and epigenetics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10.1101/cshperspect.a017905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Günther K., Rust M., Leers J., Boettger T., Scharfe M., Jarek M., Bartkuhn M., and Renkawitz R. (2013) Differential roles for MBD2 and MBD3 at methylated CpG islands, active promoters and binding to exon sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 3010–3021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Basta J., and Rauchman M. (2015) The nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex in development and disease. Transl. Res. 165, 36–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimbo T., Du Y., Grimm S. A., Dhasarathy A., Mav D., Shah R. R., Shi H., and Wade P. A. (2013) MBD3 localizes at promoters, gene bodies and enhancers of active genes. PLoS Genet. 9, e1004028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamashita D., Komori H., Higuchi Y., Yamaguchi T., Osumi T., and Hirose F. (2007) Human DNA replication-related element binding factor (hDREF) self-association via hATC domain is necessary for its nuclear accumulation and DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7563–7575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ookawa K., Tsuchida S., Adachi J., and Yokota J. (1997) Differentiation induced by RB expression and apoptosis induced by p53 expression in an osteosarcoma cell line. Oncogene 14, 1389–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uchimura Y., Nakamura M., Sugasawa K., Nakao M., and Saitoh H. (2004) Overproduction of eukaryotic SUMO-1- and SUMO-2-conjugated proteins in Escherichia coli. Anal. Biochem. 331, 204–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aubry F., Mattéi M. G., and Galibert F. (1998) Identification of a human 17p-located cDNA encoding a protein of the Snf2-like helicase family. Eur. J. Biochem. 254, 558–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hirose F., Ohshima N., Kwon E. J., Yoshida H., and Yamaguchi M. (2002) Drosophila Mi-2 negatively regulates dDREF by inhibiting its DNA-binding activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5182–5193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vethantham V., and Manley J. L. (2009) In vitro sumoylation of recombinant proteins and subsequent purification for use in enzymatic assays. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 10.1101/pdb.prot5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kamitani T., Nguyen H. P., and Yeh E. T. (1997) Preferential modification of nuclear proteins by a novel ubiquitin-like molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 14001–14004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lallemand-Breitenbach V., and de Thé H. (2010) PML nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2, a000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pirrotta V., and Li H. B. (2012) A view of nuclear Polycomb bodies. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 101–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dundr M. (2012) Nuclear bodies: multifunctional companions of the genome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 415–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ren J., Gao X., Jin C., Zhu M., Wang X., Shaw A., Wen L., Yao X., and Xue Y. (2009) Systematic study of protein sumoylation: development of a site-specific predictor of SUMOsp 2.0. Proteomics 10.1002/pmic.200800646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]