Abstract

Camelid-derived single domain VHH antibodies are highly heat resistant, and the mechanism of heat-induced VHH denaturation predominantly relies on the chemical modification of amino acids. Although chemical modification of disulfide bonds has been recognized as a cause for heat-induced denaturation of many proteins, there have been no mutagenesis studies, in which the number of disulfide bonds was controlled. In this article, we examined a series of mutants of two different VHHs with single, double or no disulfide bonds, and scrutinized the effects of these disulfide bond modifications on VHH denaturation. With the exception of one mutant, the heat resistance of VHHs decreased when the number of disulfide bonds increased. The effect of disulfide bonds on heat denaturation was more striking if the VHH had a second disulfide bond, suggesting that the contribution of disulfide shuffling is significant in proteins with multiple disulfide bonds. Furthermore, our results directly indicate that removal of a disulfide bond can indeed increase the heat resistance of a protein, irrespective of the negative impact on equilibrium thermodynamic stability.

Keywords: antibody engineering, disulfide bonds, protein chemical modification, protein engineering, protein stability

The variable domain of the camelid heavy chain antibody (VHH) is known to be highly heat resistant. VHHs remain active even after incubation at high temperatures (>80°C) because of their ability to refold to their native structure from a heat-induced unfolded state (1–6). However, even for VHHs, a long incubation finally leads to denaturation: e.g. the half-life of VHH at 90°C (t1/290°C) was 3 h at neutral pH (7). Residual activity of VHH depends only on the incubation time at 90°C, and not on the number of heating (90°C)—cooling (20°C) cycles, indicating that folding and unfolding intermediates are irrelevant to the loss of activity. Heat denaturation of VHHs is independent of protein concentration; therefore, VHHs lose their activity in a unimolecular manner, not by aggregation. This strongly suggests that chemical modifications play an important role during VHH denaturation. Indeed, replacing the Asn residues, which are prone to chemical modification, increase the heat resistance of VHHs (7).

VHHs typically have only one intramolecular disulfide bond. The introduction of a second non-canonical artificial disulfide bond connecting the amino acids at positions 49 and 69, with numbering according to Kabat et al. (8), results in a significantly higher mid-point temperature of equilibrium thermal unfolding (Tm) in comparison to wild-type protein (9–13). In spite of its superior equilibrium thermodynamic stability, the mutant with a second disulfide bond exhibited lower residual activity after 40 cycles of repetitive heating (90°C for 5 min)—cooling (20°C for 5 min) than wild-type VHH (7). On the other hand, the anti-hCG VHH mutant, which lacks the native disulfide bond but has an artificial disulfide bond, showed both lower Tm and lower heat resistance.

In addition to Asn modifications, disulfide bonds have been recognized as a major factor in the heat resistance of proteins (14–19). The relationship between equilibrium thermodynamic stability and heat resistance, in wild-type and disulfide mutants of VHHs, can be explained by the modification of disulfide bonds. Although the importance of chemical modification of disulfide bonds for heat denaturation of proteins has been suggested already a few decades ago, previous studies provided only indirect evidence by simply showing that chemical modification of cystine was accompanied by heat-induced denaturation. Controlling the number of disulfide bonds by site-specific mutagenesis will provide direct evidence that heat-induced chemical modification of disulfide bonds affects the heat resistance of proteins.

Here, we report the effect of disulfide bonds on the heat resistance of two different VHHs, anti-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) VHH (VHH-H14) and anti-Bacillus cereus β lactamase (βLA) VHH (cAbBCII10) (10, 20–23). Molecular weights of anti-hCG and anti-βLA VHHs are 12 509 and 13 828, and the isoelectric points are 9.10 and 9.13, respectively. Wild-type and disulfide mutant forms, with or without disulfide bonds, were prepared for these two VHHs, and their residual activities were measured in different conditions to elucidate how the number of disulfide bonds regulates the heat resistance of VHHs.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The antigens hCG and βLA (penicillinase) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Purchased βLA was further purified by HiTrap SP HP (GE Healthcare) equilibrated by 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7) and 1 mM ZnCl2 (24).

Preparation of VHHs

Construction of the expression vectors of wild-type and disulfide mutants of anti-hCG VHHs and wild-type anti-βLA VHH were previously described (7, 9, 25). Cys residues at positions 22 and 92 in anti-βLA VHH were replaced by Ala and Ala, or by Ala and Val through PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. The resulting mutants were cloned into pAED4 (26). VHHs were produced according to previously described methods (7, 9, 25). In brief, anti-hCG VHH mutants with double disulfide bonds were expressed in Pichia pastoris in a secreted form and purified by SP-Sepharose FF and Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Using Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain BL21(DE3) pLysS (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), the other VHHs were expressed in inclusion bodies, except for wild-type anti-βLA VHH that was soluble. Inclusion bodies were solubilized with 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) and solid guanidine hydrochloride (Gdn-HCl) at a final concentration of ∼6 M. If the protein had Cys residues, we added dithiothreitol at a final concentration of 20 mM. Anti-hCG VHHs were then purified on a Superdex 75 column in 6 M urea and 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5). Single disulfide bonds were formed by overnight air oxidation at 4°C. The samples were then dialyzed against 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.7) and further purified on a Resource S cation-exchange column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.7). Anti-βLA VHHs with a C-terminal Ala-Gly-Gly-His-His-His-His-His-His sequence were subjected to purification on 5 ml HisTrap HP columns (GE Healthcare) and eluted by a gradient of imidazole in 0.5 M NaCl and 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer at pH 8.0. Wild-type anti-βLA VHH was reduced in 6 M Gdn-HCl and 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) overnight at room temperature, extensively dialyzed against 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) to re-oxidize the disulfide bond and further purified on a Superdex 75 column. A MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer Microflex AI (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA, USA) was used to confirm that the molecular weight of the purified proteins was identical to the expected values calculated based on their amino acid sequences (with an error of ±0.025%). The concentration of VHH in the stock solution was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm (27) using a UV-2500PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan).

Heat treatment of VHHs and measurement of residual activities

The residual activities after continuous and repetitive heat treatment were analysed according to the methods described in our previous report (7). In brief, samples in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA and 0.005% surfactant P20 (HBS) were placed in 0.2 ml microtubes and incubated at high-temperature for various period of time, or subjected to a given number of heating–cooling cycles (90°C for 5 min—90°C for 5 min). Antigen hCG (0.05 mg/ml) and β-lactamase (0.025 mg/ml) were coupled to a CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) at pH 4.7 by amine coupling, and analysed on a Biacore 2000 instrument (GE Healthcare) in HBS buffer at 20°C. The standard curves were plotted using the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) values at 350 s of four to five untreated intact samples with known protein concentrations between 0.1 and 2 µg/ml. The residual activities of the heat-treated samples were determined using SPR values at 350 s and the standard curves. When the sample concentration was higher than 2 µg/ml, the sample was diluted with HBS buffer before SPR measurement. Unless noted otherwise, the residual activity of VHH was measured at a protein concentration of 100 nM. The measurements were performed at least in duplicate using a multiple-channel flow cell and averaged. Errors were calculated as standard deviations. We confirmed that the estimated residual activity of VHH using the SPR values of controls and samples at 150, 200, 250, 300 and 350 s were not significantly different (7).

Assays for thiol modification

The amount of free thiol was determined using 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) using Ellman’s method (28). Heat-treated samples were denatured by 4 M Gdn-HCl and mixed with 2 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in 4 M Gdn-HCl and 0.2 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.0). We used 13 600 as extinction coefficient of 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate. The dimer formation of hCG-VHH was examined by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS-PAGE) using 10–20% gradient gels (Oriental Instruments Co., LTD., Kanagawa, Japan). Heat-treated samples were mixed with 4 mM iodoacetamide to block reduced Cys residues, or with 10 mM dithiothreitol to reduce the disulfide bonds immediately after heating. To obtain mass spectra of heat-treated VHHs, wild-type and mutant anti-hCG VHHs (5 µM) were subjected to a continuous 1600-min incubation at 90°C in HBS buffer. The samples were mixed with the same volume of 10 mg/ml synaptic acid (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) in 80% acetonitrile with 0.1% 2,2,2-trifluoroacetic acid. MALDI-TOF mass spectra were collected using a Microflex AI instrument.

Determination of Tm of anti-βLA VHH by circular dichroism (CD)

Equilibrium thermal unfolding of anti-βLA VHH was monitored as the change in ellipticity at 222 nm using a J-820 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) and a 1-mm cell at a protein concentration of 20 µM. The heating rate was 1°C/min. The measurements were carried out in 10 mM Na-acetate (pH 5.4), as we observed aggregation after performing CD thermal unfolding experiments at neutral pH. The Tm was estimated on the basis of the two-state unfolding transition mechanism by curve fitting using Igor Pro software (WaveMetrics Inc., Lake Oswego, OR, USA) (29).

Results

A series of VHHs with various numbers of disulfide bonds

VHHs typically have one canonical intramolecular disulfide bond between Cys22 and Cys92 defined in the Kabat numbering scheme. To remove this disulfide bond, Cys residues at position 22 and 92 of wild-type anti-hCG VHH were replaced by either Trp and Ala (0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH), Ala and Ala (0-SS (AA) anti-hCG VHH), Ala and Ile (0-SS (AI) anti-hCG VHH) or Trp and Gly (0-SS (WG) anti-hCG VHH), of which the Tm at neutral pH is 46, 42, 39 and 40°C, respectively (9, 25) (Fig. 1 and Table I). Anti-hCG VHH with an additional disulfide bond at the positions of Ala49 and Ile69 in the Kabat numbering scheme (2-SS anti-hCG VHH) exhibited a Tm of 74°C, which is 10°C higher than that of wild-type anti-hCG VHH (9). The same artificial disulfide bond was introduced on the 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH sequence, resulting in 1-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH (9). We also prepared anti-βLA VHH mutants lacking disulfide bonds, by replacing the Cys residues at positions 22 and 92 by Ala and Ala (0-SS (AA) anti-βLA VHH), or Ala and Val (0-SS (AV) anti-βLA VHH). The Tm of wild-type, 0-SS (AV) and 0-SS (AA) anti-βLA VHHs at pH 5.3 is 73, 63 and 63°C, respectively (Table I). All mutants exhibited antigen binding activity equivalent to that of wild-type VHH at 20°C. In the previous paper, we carried out the screening of stable anti-hCG VHH mutants lacking disulfide bond and found that 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH exhibited the highest stability among the mutants examined (25). Thus, we select 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH as a representative VHH lacking disulfide bond; 0-SS (AA) and 0-SS (WG) anti-hCG VHHs were used to investigate the role of first Trp and second Ala in 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH. For the addition of artificial disulfide bond, Ala and Ile were replaced to cystine resulting 1-SS (WA) and 2-SS anti-hCG VHHs. To compare the effect of substitution of Ala and Ile to cystine, we prepared 0-SS (AI) anti-hCG VHH. Since it was unclear which amino acid substitutions were optimal to replace the disulfide bond without affecting the structure and function of anti-βLA VHH, we used two out of four possible Ala and Val combinations, which were sufficient to obtain natively folded Ig fold domains without disulfide bonds (25).

Fig. 1.

Wild-type and mutant anti-hCG and anti-βLA VHHs used to examine the effect of disulfide bonds on heat-induced denaturation. Amino acid sequences of wild-type anti-hCG (A) and anti-βLA (B) VHHs are shown in upper case, and the amino acids in bold and underlined are the mutation positions. The residual Met of both VHHs expressed in E. coli, and linker and His-tag anti-βLA VHH are shown in lower case. The broken lines in the schematic representation of sequences indicate the disulfide bonds, and the bold and underlined characters are the introduced mutations.

Table I.

Equilibrium thermodynamic stability and heat resistance of VHHs

| VHH | Number of disulfide bonds | Tm (°C) | t1/290°C (min) | ktime90°C (×10−3/min) | kcycles90°C (×10−3/cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-hCG | |||||

| 2-SS | 2 | 74a | 100 ± 3 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | |

| Wild-type | 1 | 64a | 174 ± 11 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | |

| 1-SS | 1 | 56a | 154 ± 6 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | |

| 0-SS (WA) | 0 | 46a | 216 ± 17 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | |

| 0-SS (AA) | 0 | 42b | 158 ± 12 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | |

| 0-SS (AI) | 0 | 39b | 201 ± 19 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | |

| 0-SS (WG) | 0 | 40b | 179 ± 15 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | |

| Anti-βLA | |||||

| Wild-type | 1 | 78c | 213 ± 15 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | |

| 0-SS (AA) | 0 | 63c | 262 ± 17 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.4 |

| 0-SS (AV) | 0 | 63c | 272 ± 20 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.4 |

disulfide bonds affect the heat resistance of VHHs

Removal of one of the two disulfide bonds of 2-SS VHH significantly increased its heat resistance. To quantitatively estimate the heat resistance of 1-SS and 2-SS anti-hCG VHHs, these VHH disulfide mutants were subjected to continuous and repetitive heat-treatments at 90°C (Fig. 2). As 1 cycle of a repetitive experiment included a 5-min incubation at high temperature, the horizontal axis for these experiments (upper) is adjusted to 1/5 of the horizontal axis for continuous experiments (lower). For the two VHHs, the denaturation curves induced by repetitive and continuous heat treatments were well matched. This suggested that the incubation time at high temperature, and not the number of the refolding process, is an important factor for denaturation, as was previously observed for wild-type VHH (7).

Fig. 2.

Heat-induced irreversible denaturation of 2-SS (A) and 1-SS (B) anti-hCG VHHs by repetitive heating–cooling cycles or continuous incubation at 90°C. Anti-hCG VHH (100 nM) was subjected to repetitive (open circle) or continuous (closed circle) incubation at 90°C. The experiments were carried out at pH 7.4 in HBS buffer. In heating–cooling cycles, a given number of reaction segments, which consisted of heating at 90°C for 5 min and cooling at 20°C for 5 min, were repeated. Thus, one cycle corresponded to 5 min of continuous incubation. The solid and broken lines represent a single exponential curve fitted to the time-dependent denaturation of wild-type and mutant VHHs, respectively. In all panels, error bars represent standard deviations.

Denaturation of anti-hCG VHHs can be simulated by a single exponential equation (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). In continuous experiments, the fraction of residual activity, fcont, can be approximated as

where ktime and t are the first-order kinetic constants of denaturation and heating time, respectively. The parameter A, which corresponds to the initial fraction of activity, should be 1 in our experimental system. However, residual activities of some VHHs increased (<6%) after a short period of incubation and A took the value between 1 and 1.06 in each experiment. In addition, we assumed that denaturation by single refolding and/or unfolding is negligible. Thus, we fitted the denaturation curves using two parameters, A and ktime. The t1/290°C of wild-type (t1/290°C = 173 min) and 1-SS (t1/290°C = 154 min) anti-hCG VHHs is about 73 and 54% longer than that of 2-SS anti-hCG VHH (t1/290°C = 100 min) (Table I).

It is unclear if the removal of the native disulfide bond between positions 22 and 92 affects the heat resistance of wild-type VHH. The four anti-hCG VHH mutants lacking the native disulfide bond were subjected to heat treatment at 90°C (Fig. 3). Denaturation curves by repetitive and continuous heat treatments were similar for 0-SS (WA) and 0-SS (AA) anti-hCG VHHs. First-order kinetic analysis revealed that the t1/290°C of 0-SS (WA), (AA), (AI) and (WG) anti-hCG VHHs is 216, 158, 201 and 179 min, respectively (Table I), and the average was 189 ± 25 min. The t1/290°C of 0-SS (WA), (AI) and (WG) anti-hCG VHHs was 25, 3 and 16% longer, but that of 0-SS (AA) anti-hCG VHH was 9% shorter than that of wild-type anti-hCG VHH. The effect of removal of the last disulfide bond is less significant than that of removal of one out of two disulfide bonds.

Fig. 3.

Heat-induced irreversible denaturation of anti-hCG VHHs lacking disulfide bonds at 90°C. 0-SS (WA) (A) and (AA) (B) anti-hCG VHHs (100 nM) were subjected to repetitive (open circle) or continuous (closed circle) incubation at 90°C. The denaturation of 0-SS (AI) (C) and 0-SS (WG) (D) anti-hCG VHHs by continuous heat treatment was also measured in HBS buffer. The solid and broken lines represent a single exponential curve fitted to the time-dependent denaturation of wild-type and mutant VHHs, respectively. In all panels, error bars represent standard deviations.

We also evaluated the effect of the removal of the native disulfide bond between the amino acids at positions 22 and 92 in anti-βLA VHH using its 0-SS (AV) and (AA) mutants (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S1B). We previously reported that the inactivation curves of wild-type anti-βLA VHH by repetitive and continuous heat treatments were almost identical, indicating that the refolding process only has a minor contribution to heat-induced irreversible denaturation (7). The t1/290°C of wild-type, 0-SS (AV) and (AA) anti-βLA VHH was estimated as 213, 272 and 262 min, respectively. The removal of a disulfide bond extended t1/290°C with 28% in 0-SS (AV) anti-βLA VHH and with 23% in 0-SS (AA) anti-βLA VHH.

Fig. 4.

Heat-induced irreversible denaturation of anti-βLA VHHs lacking disulfide bonds at 90°C. Anti-βLA hCG mutants (100 nM), 0-SS (AA) (A) and 0-SS (AV) (B) were subjected to repetitive (open circle) or continuous (closed circle) incubation at 90°C at pH 7.4 in HBS buffer. The solid and broken lines represent a single exponential curve fitted to the time-dependent denaturation of wild-type and mutant VHHs, respectively. The insets show the ratio of residual activities in repetitive and continuous experiments at the same total incubation time, and the broken line represents the theoretical curve fitted by a single exponential equation. Error bars represent standard deviations.

The denaturation of the disulfide mutants of anti-βLA VHH by repetitive heat treatment was faster than that by continuous treatment. This suggested that aggregation of folding intermediates and/or misfolding from the unfolded state may be involved in the heat-induced denaturation process. At high protein concentrations (20 µM), we observed aggregation after heat denaturation. In the repetitive experiment, the fraction of residual activity, frep, can be approximated as

where kcycle and n are the kinetic constant related to the refolding and/or unfolding process and number of heating-cooling cycles, respectively. In the continuous experiment, n is one, and thus the ratio of residual activity in two experiments with the same total incubation time (Fig. 4, insets) can be described as

where we assumed that parameter A is identical in the two experiments. The estimated kcycle of 0-SS (AV) and (AA) anti-βLA VHH is 5.2 and 4.9 × 10−3/cycles, respectively. In brief, 0.5% of antigen binding activity is lost in the first heating-cooling cycle in both VHH mutants.

The effect of protein concentration on residual activity after continuous heat treatment was measured to evaluate the aggregation of VHHs in a heat-induced unfolded state (Fig. 5). Denaturation of 2-SS, 1-SS and 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHHs was dependent on the protein concentration when it was higher than 1, 10 and 100 µM, respectively. At lower protein concentrations, we observed no marked changes in denaturation, and aggregation of these anti-hCG VHHs in a heat-induced unfolded state was not a major origin of denaturation. We used 100 nM of anti-hCG VHH mutants in all experiments, except when testing the protein concentration dependency of denaturation. Heat-induced denaturation of wild-type VHH was not significantly affected by the protein concentration, not even when it was higher than 100 µM (7).

Fig. 5.

The effect of protein concentration on VHH denaturation. Wild-type, 1-SS and 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHHs at different concentrations in HBS buffer (pH 7.4) were subjected to 400 min continuous heat treatment at 90°C. As the residual activity of 2-SS anti-hCG VHH was <10% after 400 min heat treatment, the concentration dependency of residual activity of 2-SS anti-hCG VHH was estimated based on 200 min incubation at 90°C. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Heat resistance is irrelevant to equilibrium thermodynamic stability

It is evident that heat resistance against 90°C was not positively correlated with the equilibrium thermodynamic stability, represented by the Tm value (Fig. 6 and Table I). The removal of the native disulfide bond from wild-type anti-hCG and anti-βLA VHHs significantly reduced Tm (−15 to −25°C) (9, 25). The changes in t1/290°C of mutants lacking disulfide bonds were dependent on the amino acid pair used to replace the disulfide bond, and ranged from −9 to 27% (−15 to 59 min) as compared with wild-type VHH. On average, t1/290°C deviation between wild-type and 0-SS mutants was 14 ± 14% (28 ± 28 min). The changes of Tm and t1/290°C for 2-SS anti-hCG VHH were −10°C and 73% (compared with wild-type) and −18°C and 54% (compared with 1-SS). Introduction of disulfide bonds resulted in an increase of Tm and a decrease of t1/290°C, however both parameters were apparently dependent on the position of the mutation, the introduced amino acid pair and the VHH species.

Fig. 6.

The relationship between equilibrium thermodynamic stability and heat resistance of VHHs. The t1/290°C of wild-type and mutant anti-hCG and anti-βLA VHHs are plotted against the difference in Tm with wild-type VHH. VHHs with a different number of disulfide bonds were grouped by broken lines. Error bars represent standard deviations in the curve fitting analysis of the denaturation curves.

The half-life of VHHs at temperatures <90°C was also unrelated to the Tm. The measurements of residual activities after incubation for 200 min at a series of different temperatures showed that the orders of heat resistance of each VHH between 75 and 85°C were identical to the order at 90°C (Fig. 7). It should be noted that half of the 2-SS anti-hCG VHH molecules form the native structure at 75°C, although most of 0-SS (WA), 1-SS and wild-type anti-hCG VHHs were unfolded at the same temperature, suggesting that heat-induced denaturation proceeds even in the equilibrium condition where the native and unfolded states coexist. This result was somehow surprising for us, as we considered that the tightly packed native structure might significantly hamper the formation of chemical modifications. At temperatures below 65°C, the folded fraction of each VHH is largely different. For example, at 65°C, the fraction of unfolded 0-SS (WA), 1-SS, wild-type and 2-SS anti-hCG VHH molecules was 100, 100, 50 and 0%, respectively (9). Regardless of the ratio of molecules in the native state, the antigen binding ability of all VHHs was almost fully conserved after incubation at temperatures below 65°C for 200 min, indicating that the accumulation of chemical modifications was negligible under these conditions.

Fig. 7.

Temperature dependency of denaturation of wild-type and disulfide mutants of VHHs. Wild-type, 2-SS, 1-SS and 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHHs (100 nM) were subjected to continuous incubation for 200 min at different temperatures in HBS buffer (pH 7.4). Error bars represent standard deviations.

Analysis of the chemical modifications caused by heat treatment at 90°C

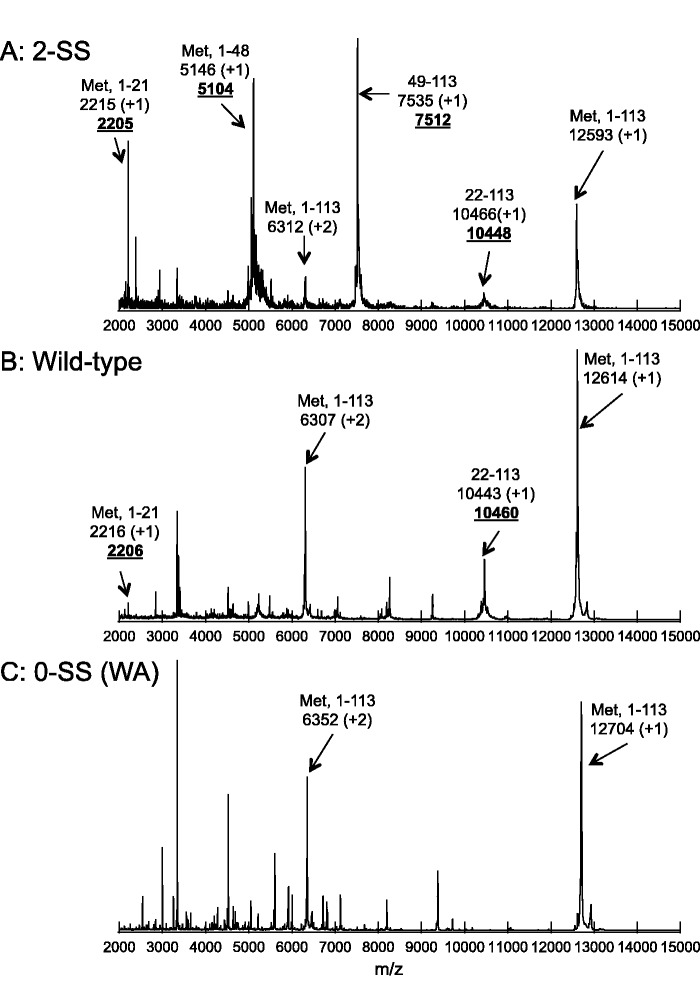

Long-term incubation of VHHs at 90°C causes fragmentation into polypeptide chains as observed in mass spectrometry. A part of these fragmentations originate at chemical modifications of Asn residues, and, as a result, mutation of Asn reduced the number of fragments (7). However, a few fragments remained even in the Asn mutant (7). Two of the remaining fragments can be identified as peptides cleaved at the N-terminus of Cys22. To assess this possibility, the fragmentation of 0-SS (WA) and 2-SS anti-hCG VHH was examined after heat treatment at 90°C. As expected, a few of the fragments observed for wild-type VHH were absent for 0-SS (WA) anti-hCG VHH (Fig. 8). On the other hand, introduction of an additional disulfide bond resulted in new fragments (Fig. 8), which may correspond to a cleavage at the N-terminus of Cys49. These results suggested that heat treatment of VHHs causes fragmentation of polypeptide around the position of the disulfide bond as previously reported (30, 31).

Fig. 8.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of 2-SS (A), wild-type (B) and 0-SS (WA) (C) anti-hCG VHHs after heat treatment. The samples (5 µM) were incubated for 1600 min at 90°C in HBS buffer (pH 7.4). The arrows indicate full length VHH and hypothetical fragments resulting from digestion occurring at the cystines. The numbers at second line show the calculated molecular weight of hypothetical fragments with protonation states in parenthesis. The bold and underlined numbers at third line are measured m/z.

Heat treatment affects the side chain structure of Cys in VHH. First the amount of total thiol groups in wild-type anti-hCG VHH was quantified by Ellman’s method (28). After reduction in the presence of denaturant, the molar ratio between reactive thiol groups and VHH was 2.0 ± 0.1 without heat treatment. Continuous exposure of wild-type anti-hCG VHH to 90°C for 200 min reduced the molar ratio to 1.7 ± 0.1, indicating that the chemical structure of cystine was destroyed. This result indicated that 15 (both thiols of cystine modified) to 30 (single thiol of cystine modified)% of the VHH molecule had aberrant Cys. On the other hand, the incubation at 90°C for 200 min caused a reduction in antigen binding of ∼60%, suggesting that denaturation is influenced by other factors than the modification of the disulfide bond. Indeed, we have shown that Asn modification is one of the key factors for denaturation of VHHs (7).

We observed the dimer formation of wild-type anti-hCG VHH through the connection of free reactive thiol groups on Cys caused by heat-induced chemical modification (Fig. 9). Without heat treatment, there are no bands corresponding to the dimer detected in an SDS-PAGE experiment. After incubation at 90°C for 200 min, a VHH species with a larger molecular weight was visible, suggesting that reactive groups had formed an intermolecular covalent bond upon heat treatment. It should be noted that only one of the two bands whose migration pattern corresponded to the expected size of the dimer was sensitive to treatment with a reducing reagent, suggesting that a dimer can be formed by covalent bonding other than a disulfide bond.

Fig. 9.

Heat-induced dimer formation of wild-type VHH. (A) Different concentrations of wild-type anti-hCG VHH, with and without heat treatment (90°C for 200 min in HBS buffer at pH 7.4), were analysed by SDS-PAGE. Different concentrations of untreated and heated samples were run on lanes 3–7, and lanes 9–13, respectively, under non-reducing condition. (B) After incubation at 90°C for 200 min, 50 and 100 µM of wild-type anti-hCG VHH were alkylated by iodoacetamide (lanes 4 and 5) and reduced by dithiothreitol (lanes 6 and 7). As a control, samples without heat treatment were run on lanes 2 and 3. Molecular weight markers were subjected to lane 1 and the numbers on the left of the panels indicate the molecular weights of marker proteins. The lane numbers are shown at the top of the panels.

Discussion

By using disulfide mutants of VHH, we showed that removal of disulfide bonds can increase the heat resistance of VHHs, contrary to the their negative effect on the equilibrium thermodynamic stability. It is well known that disulfide bonds are a major factor in the heat resistance of proteins. In prior studies, experiments were carried out using proteins with multiple disulfide bonds, such as lysozymes, or with disulfide bonds with free thiols, such as β-lactoglobulin (14–19). Thus, it was still unclear how chemical modification affects the heat resistance of proteins with a single disulfide bond without free Cys, in which the intramolecular disulfide bond exchange cannot occur. Our results suggested that even a single disulfide bond influences the heat resistance of a protein. The t1/290°C of the mutants lacking the native disulfide bond was maximum 28% longer than that of wild-type VHH. On average, removal of the native disulfide from wild-type anti-hCG and anti-βLA resulted in a 14 ± 14% increase in t1/290°C. It should be noted that removal of the artificial disulfide bond between Cys49 and Cys69 of 1-SS VHH increased t1/290°C by 40%. Only a small amount of covalently linked dimers was observed by SDS-PAGE analysis of heat-treated samples, and the denaturation depended a little on the protein concentration, suggesting that the denaturation was not caused by the intermolecular disulfide exchange, but by the change of chemical structure of Cys. The equilibrium thermodynamic stability of immunoglobulin fold domains lacking the native disulfide bond depends largely on the substituting amino acid pair (25). Therefore, the heat-induced change of Cys side-chain structure affects the equilibrium thermodynamic stability and may induce the destruction or unfolding of VHH. It was also reported that VHHs lacking the disulfide bond formed non-covalently connected homodimers (32). Heat-induced chemical modification of disulfide bonds may make VHHs prone to be aberrant dimerization, and thus results in the loss of antigen binding ability.

Reducing the number of disulfide bonds from 2 to 1 had a larger effect than a reduction from 1 to 0. We found that the anti-hCG VHH with double disulfide bonds was short-lived at 90°C, whereas the t1/290°C of wild-type and 1-SS anti-hCG VHHs was 73 and 54% longer than that of 2-SS anti-hCG VHH, respectively. Replacement of the native disulfide bond between amino acids 22 and 92 in wild-type VHH resulted in a 14% t1/290°C increase on average, and 28% t1/290°C increase at maximum. Removal of the second disulfide bond also leads to the disappearance of disulfide exchange, which may explain the different effect of disulfide replacement from VHHs with single and double disulfide bonds. This is consistent with previous reports showing that heat-induced denaturation at neutral pH was mainly caused by intra- and intermolecular disulfide exchange in a protein with multiple disulfide bonds (14, 15, 17, 19).

Reactive-free thiol can be formed either by attack of a hydroxyl anion on a sulfur atom, or by α-elimination and β-elimination reactions on disulfide bonds (33–37). Thus, all three reactions may contribute to the disulfide exchange in a protein with multiple disulfide bonds, causing heat-induced denaturation by incorrect disulfide linkage. An α-elimination reaction of a disulfide bond forms chemically modified species, such as thiol-aldehyde species. β-elimination reaction introduces unnatural chemical structures, such as thioethers, into VHH molecules or leads to cleavage of the peptide bonds. A covalent bond between a residual Cys and an adjacent amino group can be formed by both reactions. These modifications are irrelevant to the disulfide exchange and thus may be a source of denaturation of VHHs with a single disulfide bond. A decreased amount of thiol groups on wild-type anti-hCG VHH after heat treatment and fragmentation around Cys residues suggested the occurrence of α-elimination and β-elimination. In addition, the presence of dimers, even after reduction, strongly supports that α-elimination and/or β-elimination reactions have taken place.

The effect of heat-induced modification of cystine in wild-type VHH is less striking than that of Asn. We previously reported that replacement of all of three Asn residues in anti-hCG VHH increased the t1/290°C by more than 50% (7). On the other hand, the increase of t1/290°C by removal of cystine from wild-type anti-hCG VHH was only 25% at best. The disulfide modification, excluding disulfide exchange, may be slower and less frequent than modifications of three Asn residues. Alternatively, the effect of the chemical modifications itself on VHH structure, thermodynamic stability and antigen binding function could be more severe in the case of Asn than in the case of cystine. In contrast, the effect of cystine removal from 2-SS anti-hCG VHH on t1/290°C is comparable to or larger than that of replacement of Asn. It was reported that heat-induced denaturation of lysozyme at pH 8 at 100°C is controlled by heat-induced disulfide exchange, and that deamidation plays only a minor role (14, 15). Lysozyme has four disulfide bonds, and the occurrence of reactive free thiol groups and subsequent disulfide exchange should be more critical in lysozyme than in 2-SS anti-hCG VHH. Thus, the contribution of Asn modification could be relatively small for lysozyme at neutral pH.

The consistency in denaturation curves for continuous and repetitive heat treatments indicated that refolding and/or unfolding processes play a minor role in the denaturation of wild-type anti-hCG and βLA VHHs (7). Although this is also true for a series of anti-hCG VHH mutants, the 0-SS (AA) and (AV) anti-βLA VHH mutants exhibited different denaturation profiles for continuous and repetitive heat treatments. Based on the differences between the two experiments, we estimated that a single process of heating at 90°C and cooling at 20°C reduces the activity of these anti-βLA VHHs by 0.5% at a protein concentration of 100 nM and neutral pH. The recovery from heat treatment is still highly efficient in anti-βLA VHH mutants; however, it is clear that the mutation negatively affects the biophysical characteristics of anti-βLA VHH. In addition, in contrast to the wild-type anti-hCG VHH, protein concentration dependencies of heat denaturation were observed in 2-SS, 1-SS and 0-SS (WA) mutants at >1 µM of protein concentration. Recently, Turner et al. (38) reported the heat resistance of three different VHHs and their mutants with different charge distribution. Although the heat resistance of these VHHs was generally high, one of the wild-type VHHs was only marginally heat tolerant at 72°C. Mutations introducing more negatively charged amino acids than parental VHH improved the heat resistance. However, the same type of mutations on intrinsically heat resistant VHH decreased the amount of activity of VHH after heat treatment, and thus had the inverse effect. In conclusion, mutations could alter the heat denaturation mechanism and their total effect may vary across VHH species.

The introduction of an additional disulfide bond at Ala49 and Ile69 by protein engineering (9, 10) is becoming a general approach to increase the equilibrium thermodynamic stability of VHHs (11). This mutation also increased resistance against pepsin (12, 39) and was applicable to VH domains from other species than camelid (40, 41). In spite of the efficiency of this mutation to stabilize VHHs and VHs thermodynamically, our data suggest caution when the mutated protein will be used in conditions that accelerate the chemical modification of cystine. This issue was already alerted by Volkin and Klibanov (19) almost 30 years ago, “Since it is likely that a cleavage or reshuffling of –S–S– bonds will inactivate an enzyme, one should conclude that it is unwise to genetically engineer new Cys residues in enzymes that are to work at high temperatures for prolonged periods of time.” This notion is true and apparently raised questions on the power of protein engineering. However, we believe that precise analysis of the effect of each mutation will help find the appropriate engineering approach to match a given objective, such as the strategy presented here showing that reinforcement of VHH against heat-treatment can be achieved by removing disulfide bonds.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data are available at JB Online.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations

- βLA

Bacillus cereus β lactamase

- CD

circular dichroism

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- t1/290°C

half-life of VHH at 90°C

- Tm

mid-point temperature of thermal unfolding

- VHH

variable domain of camelid heavy chain antibody

References

- 1.van der Linden R.H., Frenken L.G., de Geus B., Harmsen M.M., Ruuls R.C., Stok W., de Ron L., Wilson S., Davis P., Verrips C.T. (1999) Comparison of physical chemical properties of llama VHH antibody fragments and mouse monoclonal antibodies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1431, 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez J.M., Renisio J.G., Prompers J.J., van Platerink C.J., Cambillau C., Darbon H., Frenken L.G. (2001) Thermal unfolding of a llama antibody fragment: a two-state reversible process. Biochemistry 40, 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumoulin M., Conrath K., Van Meirhaeghe A., Meersman F., Heremans K., Frenken L.G., Muyldermans S., Wyns L., Matagne A. (2002) Single-domain antibody fragments with high conformational stability. Protein Sci. 11, 500–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladenson R.C., Crimmins D.L., Landt Y., Ladenson J.H. (2006) Isolation and characterization of a thermally stable recombinant anti-caffeine heavy-chain antibody fragment. Anal. Chem. 78, 4501–4508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omidfar K., Rasaee M.J., Kashanian S., Paknejad M., Bathaie Z. (2007) Studies of thermostability in Camelus bactrianus (Bactrian camel) single-domain antibody specific for the mutant epidermal-growth-factor receptor expressed by Pichia. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 46, 41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewert S., Cambillau C., Conrath K., Plückthun A. (2002) Biophysical properties of camelid V(HH) domains compared to those of human V(H)3 domains. Biochemistry 41, 3628–3636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akazawa-Ogawa Y., Takashima M., Lee Y.H., Ikegami T., Goto Y., Uegaki K., Hagihara Y. (2014) Heat-induced irreversible denaturation of the camelid single domain VHH antibody is governed by chemical modifications. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15666–15679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabat, E.A., Wu, T.T., Perry, H.M., Gottsman, K.S., and Foeller, C. (1991) Sequences of Proteins of Immunologic Interest, 5th edn. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

- 9.Hagihara Y., Mine S., Uegaki K. (2007) Stabilization of an immunoglobulin fold domain by an engineered disulfide bond at the buried hydrophobic region. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36489–36495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saerens D., Conrath K., Govaert J., Muyldermans S. (2008) Disulfide bond introduction for general stabilization of immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable domains. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagihara Y., Saerens D. (2014) Engineering disulfide bonds within an antibody. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1844, 2016–2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussack G., Hirama T., Ding W., Mackenzie R., Tanha J. (2011) Engineered single-domain antibodies with high protease resistance and thermal stability. PLoS One 6, e28218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walper S.A., Liu J.L., Zabetakis D., Anderson G.P., Goldman E.R. (2014) Development and evaluation of single domain antibodies for vaccinia and the L1 antigen. PLoS One 9, e106263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomizawa H., Yamada H., Tanigawa K., Imoto T. (1995) Effects of additives on irreversible inactivation of lysozyme at neutral pH and 100 degrees C. J. Biochem. 117, 369–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahern T.J., Klibanov A.M. (1985) The mechanisms of irreversible enzyme inactivation at 100°C. Science 228, 1280–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimada K., Cheftel J.C. (1989) Sulfhydryl-group disulfide bond interchange reactions during heat-induced gelation of whey-protein isolate. J. Agrc. Food Chem. 37, 161–168 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko R., Kitabatake N. (1999) Heat-induced formation of intermolecular disulfide linkages between thaumatin molecules that do not contain cysteine residues. J. Agrc. Food Chem. 47, 4950–4955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu I., Heel T., Arnold F.H. (2013) Role of cysteine residues in thermal inactivation of fungal Cel6A cellobiohydrolases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1834, 1539–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volkin D.B., Klibanov A.M. (1987) Thermal destruction processes in proteins involving cystine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 2945–2950 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renisio J.G., Perez J., Czisch M., Guenneugues M., Bornet O., Frenken L., Cambillau C., Darbon H. (2002) Solution structure and backbone dynamics of an antigen-free heavy chain variable domain (VHH) from llama. Proteins 47, 546–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conrath K.E., Lauwereys M., Galleni M., Matagne A., Frere J.M., Kinne J., Wyns L., Muyldermans S. (2001) β-lactamase inhibitors derived from single-domain antibody fragments elicited in the camelidae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2807–2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagihara Y., Saerens D. (2012) Improvement of single domain antibody stability by disulfide bond introduction. Methods Mol. Biol. 911, 399–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saerens D., Pellis M., Loris R., Pardon E., Dumoulin M., Matagne A., Wyns L., Muyldermans S., Conrath K. (2005) Identification of a universal VHH framework to graft non-canonical antigen-binding loops of camel single-domain antibodies. J. Mol. Biol. 352, 597–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies R.B., Abraham E.P. (1974) Separation, purification and properties of β-lactamase I and β-lactamase II from Bacillus cereus 569/H/9. Biochem. J. 143, 115–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagihara Y., Matsuda T., Yumoto N. (2005) Cellular quality control screening to identify amino acid pairs for substituting the disulfide bonds in immunoglobulin fold domains. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24752–24758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doering D.S., Matsudaira P. (1996) Cysteine scanning mutagenesis at 40 of 76 positions in villin headpiece maps the F-actin binding site and structural features of the domain. Biochemistry 35, 12677–12685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edelhoch H. (1967) Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry 6, 1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellman G.L. (1958) A colorimetric method for determining low concentrations of mercaptans. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 74, 443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Privalov P.L., Gill S.J. (1988) Stability of protein structure and hydrophobic interaction. Adv. Protein Chem. 39, 191–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vlasak J., Ionescu R. (2011) Fragmentation of monoclonal antibodies. MAbs 3, 253–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S.L., Price C., Vlasak J. (2007) β-elimination and peptide bond hydrolysis: two distinct mechanisms of human IgG1 hinge fragmentation upon storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6976–6977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George J., Compton J.R., Leary D.H., Olson M.A., Legler P.M. (2014) Structural and mutational analysis of a monomeric and dimeric form of a single domain antibody with implications for protein misfolding. Proteins 82, 3101–3116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nashef A.S., Osuga D.T., Lee H.S., Ahmed A.I., Whitaker J.R., Feeney R.E. (1977) Effects of alkali on proteins–disulfides and their products. J. Agrc. Food Chem. 25, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Florence T. M. (1980) Degradation of protein disulfide bonds in dilute alkali. Biochem. J. 189, 507–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trivedi M.V., Laurence J.S., Siahaan T.J. (2009) The role of thiols and disulfides on protein stability. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 10, 614–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He H.T., Gursoy R.N., Kupczyk-Subotkowska L., Tian J., Williams T., Siahaan T.J. (2006) Synthesis and chemical stability of a disulfide bond in a model cyclic pentapeptide: cyclo(1,4)-Cys-Gly-Phe-Cys-Gly-OH. J. Pharm. Sci. 95, 2222–2234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helmerhorst E., Stokes G.B. (1983) Generation of an acid-stable and protein-bound persulfide-like residue in alkali- or sulfhydryl-treated insulin by a mechanism consonant with the β-elimination hypothesis of disulfide bond lysis. Biochemistry 22, 69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner K.B., Liu J.L., Zabetakis D., Lee A.B., Anderson G.P., Goldman E.R. (2015) Improving the biophysical properties of anti-ricin single-domain antibodies. Biotechnol. Rep. 6, 27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hussack G., Riazi A., Ryan S., van Faassen H., Mackenzie R., Tanha J., Arbabi-Ghahroudi M. (2014) Protease-resistant single-domain antibodies inhibit Campylobacter jejuni motility. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 27, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D.Y., Kandalaft H., Ding W., Ryan S., van Faassen H., Hirama T., Foote S.J., MacKenzie R., Tanha J. (2012) Disulfide linkage engineering for improving biophysical properties of human VH domains. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 25, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McConnell A.D., Spasojevich V., Macomber J.L., Krapf I.P., Chen A., Sheffer J.C., Berkebile A., Horlick R.A., Neben S., King D.J., Bowers P.M. (2013) An integrated approach to extreme thermostabilization and affinity maturation of an antibody. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 26, 151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.