Abstract

Aims

Dual therapy comprising G-CSF for mobilization of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells (BMPCs), with simultaneous pharmacological inhibition of dipeptidylpeptidase-IV for enhanced myocardial recruitment of circulating BMPC via the SDF-1α/CXCR4-axis, has been shown to improve survival after acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Using an innovative method to provide non-invasive serial in vivo measurements and information on metabolic processes, we aimed to substantiate the possible effects of this therapeutic concept on cardiac remodelling after AMI using 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET).

Methods and results

AMI was induced in C57BL/6 mice by performing surgical ligation of the left anterior descending artery in these mice. Animals were then treated with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor + Sitagliptin (GS) or placebo for a duration of 5 days following AMI. From serial PET scans, we verified that the infarct size in GS-treated mice (n = 13) was significantly reduced at Day 30 after AMI when compared with the mice receiving placebo (n = 10). Analyses showed a normalized FDG uptake on Day 6 in GS-treated mice, indicating an attenuation of the cardiac inflammatory response to AMI in treated animals. Furthermore, flow cytometry showed a significant increase in the anti-inflammatory M2-macrophages subpopulation in GS-treated animals. In comparing GS treated with placebo animals, those receiving GS-therapy showed a reduction in myocardial hypertrophy and left ventricular dilatation, which indicates the beneficial effect of GS treatment on cardiac remodelling. Remarkably, flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry showed an increase of myocardial c-kit positive cells in treated mice (n = 12 in both groups).

Conclusion

Using the innovative method of micro-PET for non-invasive serial in vivo measurements of metabolic myocardial processes in mice, we were able to provide mechanistic evidence that GS therapy improves cardiac regeneration and reduces adverse remodelling after AMI.

Keywords: cardiac remodelling, acute myocardial infarction, Sitagliptin, G-CSF, positron emission tomography, C-kit

Introduction

Ischaemic cardiomyopathy is one of the main causes of death in the Western world. Given the irreversible loss of cardiomyocytes that follows myocardial ischaemia, together with a global shortage of donor organs for transplantation, new cell-based strategies such as the stimulation of cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction are urgently needed. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells can contribute to efficient cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction, mainly through paracrine repair mechanisms such as neovascularization, the prevention of apoptosis and the stimulation of resident progenitor cells in cardiac tissue.1–4 Recently, our group has introduced a new therapeutic concept for the prevention of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction (AMI). That is, dual therapy comprising granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) for the mobilization of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells (BMPCs) to peripheral blood in conjunction with pharmacological dipeptidylpeptidase-IV (DPP-IV) inhibition by Sitagliptin for enhanced myocardial recruitment of circulating BMPC via the SDF-1α/CXCR4-axis.5–7 The underlying mechanism of DPP-IV inhibition is the reduction of local SDF-1α cleavage, which thus promotes enhanced recruitment of circulating CXCR4-positive progenitor cells to the ischaemic myocardium. This dual treatment approach has previously been proved to significantly enhance survival rates after myocardial infarction.7 As the experimental techniques commonly used in the field, such as flow cytometry, millar tip catheterization, and histology are highly invasive and thus lethal to the animals, we currently lack serial in vivo investigations focusing on the process of cardiac regeneration and adverse remodelling.

Thus, we aimed to analyse the effect of GS therapy on cardiac remodelling and regeneration after AMI by using small-animal functional 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) as a method that uniquely allows for reliable non-invasive, serial, high-resolution in vivo studies. Beyond that, FDG-PET provides standardized in vivo information on metabolic processes, which we hypothesized will provide important mechanistic insights into the mode of action of GS therapy.

Material and methods

Animal model

Male C57/BL6 mice were purchased from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). AMI was induced in 10-week-old male C57BL/6 mice by surgical occlusion of the left anterior descending artery, as described previously.8 Animal care and all experimental procedures were performed in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). All animals received humane care. Study protocols comply with the institution's guidelines and were approved by the Government's animal ethics committee.

Administration of Sitagliptin and G-CSF

After the surgical procedure, mice were randomly assigned to the treatment group (Sitagliptin + G-CSF) and the control group (saline). To ensure continuous and adequate drug ingestion, Sitagliptin (500 mg/kg/day) was administered orally via Sitagliptin-loaded feed pellets for a period of 6 days (Day 0–Day 5 after AMI). These feed pellets were obtained from ssniff Spezialdiaeten GmbH (Soest, Germany). The dosage had been titrated for significant DPP-IV-inhibition previously, taking into account average amount of food intake after AMI and body weight of animals.9 G-CSF (100 µg/kg/day) and saline (0.9% NaCl) were administered intraperitoneally for a period of 6 days (Day 0–Day 5). Treatment was commenced immediately after the surgical procedure.

In vivo cardiac PET imaging

PET scans were performed on Day 6 and Day 30 after AMI, using a dedicated small-animal PET scanner (Inveon Dedicated PET, Preclinical Solutions, Siemens Healthcare Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN, USA; n = 13 for the treatment group, n = 10 for the control group). The animals had free access to food and water until just prior to the scan. Anaesthesia was induced (2.5%) and maintained (1.5%) with isoflurane delivered in pure oxygen at a rate of 1.2 L/min via a face mask. After placing an intravenous catheter into a tail vein, 23 ± 3 MBq of FDG was injected in a volume of ∼100 µL. The catheter was immediately flushed with 50 µL of saline solution. Animals remained anaesthetized during the entire scan and were placed within the aperture of the tomograph in a prone position.

A three-dimensional PET recording was obtained in list mode during the interval of 30–45 min after tracer injection. For attenuation and scatter correction, a 7-min transmission scan was performed with a rotating [57Co] source immediately after each PET scan, as described previously.10 Recovery from anaesthesia and the PET scan was monitored closely in the home cage with monitoring by a veterinarian.

All data were processed with the Inveon Acquisition Workplace (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA). FDG list-mode acquisitions were reconstructed as static images using an OSEM 3D algorithm with four iterations and an MAP 3D algorithm with 32 iterations. The final images consisted of a 128 × 128 matrix with a zoom value of 211%, as described previously.10 All data were normalized and corrected for random, decay, and dead time as well as scatter and attenuation.

PET image analysis

Infarct sizes were determined from static FDG-PET images using commercially available software (QPS 2012®, Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, CA, USA) that created polar maps of the left ventricle. The extent of the non-viable myocardium was calculated as a percentage of the total left ventricle surface area using a normative database, which comprised information on left ventricle surface area for strain, gender, and age-matched animals, as described previously.11–13 In order to adapt small-animal PET data for software designed for human studies, the voxel size had to be magnified by a factor of 10, as described previously.14,15

PET images were analysed using the Inveon Research Workplace (Siemens Medical Solutions) for calculation of the percentage of the injected dose per gram (%ID/g) in the myocardium and the normal muscle. Inveon Research Workplace was also used for assessing the left ventricular metabolic volume (LVMV) for measurement of myocardial hypertrophy. Therefore, a cubic volume of interest (VOI) was drawn around the left ventricle and a threshold value of 30% of the hottest voxels was applied. The threshold of 30% was selected since it provided the best visual representation of the left ventricular tracer uptake. For calculating the %ID/g of the skeletal muscle, a standardized VOI of 22 µL was placed in the left thigh. Correct VOI placement was always verified in axial, sagittal, and coronal projections.

The authors have validated this technique for evaluation of myocardial hypertrophy in detail in a separate study, which is in preparation for publication at the moment and which proves that this method is valid and accurate for measuring LV hypertrophy. In a mouse model of myocardial hypertrophy (transverse-aortic-constriction model), the LVMV, obtained by PET imaging, was correlated to the left ventricular weight in milligram. Right after the PET imaging, mice were sacrificed and the left ventricle was excised. LV weight was measured using a special accuracy-weighing machine under standardized conditions. There was a very strong correlation between PET LVMV in microlitre and LV weight in milligram (R = 0.915, P < 0.001, unpublished data).

Histology

At Day 30, hearts were excised (n = 13 for the treatment group, n = 10 for the control group). After fixation in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin, hearts were cut into 2 mm thick slices and embedded in paraffin. Five micrometre thick sections were cut and mounted on positively charged glass slides. Standard histological procedures (haematoxylin/eosin and Masson's trichrome) were performed. Infarct size was determined as area of infarction correlated to the area of the left ventricle (including LV septum) in four different slices from the base to the apex of a heart. Total infarct size was calculated by multiplication of the mean percent value of the circular infarct area with the quotient: vertical extension of the infarct area/total ventricular extension, as described before.8 The histopathological inflammatory cells score was evaluated from 10 high power fields within the remote myocardium and classified based on the ratio between the number of inflammatory cells and the number of cardiomyocytes.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was done on 5 µm thick sections. CD117 (c-Kit) polyclonal rabbit antibody (Cat.No. A4502, Dako, Hamburg, Germany) was used as primary antibody at 1:300 dilution for 60 min. Pre-treatment for antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving for 2 × 15 min at 750 W in Target Retrieval Solution (Cat.No. S1699, Dako). Detection was performed using ImmPress Reagent Kit Anti-Rabbit Ig (Cat. No MP-7401, Vector Laboratories, Bulingame, CA, USA). DAB+ (Cat.No. K3468, Dako) was used as a chromogen. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin (Cat. No. H-3401, Vector). Analyses were performed as previously described.5

Flow cytometry of non-myocyte cardiac cells

Ten-week-old infarcted C57BL/6 mice were treated with either G-CSF (100 µg/kg/day) and Sitagliptin (500 mg/kg/day) or saline (0.9% NaCl) for 6 days. Cells were separated as previously described.8 The following monoclonal antibodies were used: c-kit-FITC, CD31-PE, Flk-PE, F4/80-PerCP, CD206-PE, Gr-1-PE (all from BD Pharmingen). Matching isotype antibodies (BD Pharmingen) served as controls. Cells were analysed by three-colour flow cytometry using a Coulter Epics XL-MCLTM flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

Cardiac cells from infarcted hearts of C56BL/6 mice treated with G-CSF and Sitagliptin (treatment group, n = 12) or saline (control group, n = 12) were analysed at Day 6 after myocardial infarction. Therefore, a ‘myocyte-depleted’ cardiac cell population was prepared by incubating minced myocardium in 0.1% collagenase IV (GIBCO BrL) at 37°C for 30 min, which is lethal to most adult mouse cardiomyocytes.16 Cells were then filtered through a 70 µm mesh. Cells were labelled with c-kit-FITC, CD31-PE, Flk-PE F4/80-PerCP, CD206-PE, Gr-1-PE (all from BD Pharmingen), and subjected to flow cytometry using EPICS XLMCL flow cytometer and Expo32 ADC Xa software (Beckman Coulter). Each analysis included 50 000 events.

Statistical analyses

All results were expressed as means with standard error of the mean. The paired and unpaired Student's t-tests were used where appropriate. For groups without normal distribution, the Wilcoxon signed-rank or the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. The differences were considered statistically significant at a P-value of <0.05.

Results

Sitagliptin + G-CSF reduces infarct size

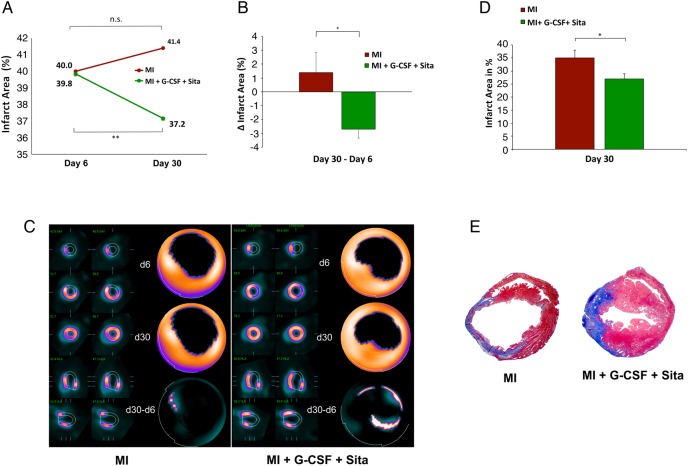

As shown by FDG-PET, treatment and control group had similar infarct sizes on Day 6 after AMI (40.0 ± 9.3 vs. 39.8 ± 9.3%; P = n.s.; Figure 1A). However, GS-treated animals showed a significant reduction in infarct size on Day 30 after AMI (37.4 ± 4.7%; P = 0.002; Figure 1A). On the contrary, there was a small, non-significant increase in infarct size from Day 6 to Day 30 in placebo-treated animals (Figure 1A). Representative static FDG-PET images are depicted in Figure 1C. As is shown in Figure 1C, infarct size alterations over time (Δ infarct area; d30–d6) significantly favours GS-treated animals compared with placebo (−2.7 ± 0.7 vs. +1.4 ± 1.4%, P = 0.015; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Sitagliptin + G-CSF reduces infarct size after AMI. (A) Small-animal FDG-PET. Comparable infarct sizes for GS-treated and placebo animals on Day 6 after AMI. Significant infarct size reduction in GS-treated animals on Day 30 after AMI compared with placebo (P = 0.002). (B) Small-animal FDG-PET. Infarct size alterations over time (Δ infarct area; d30–d6) are significantly in favour of GS-treated animals compared with placebo animals (P = 0.015). (C) Representative static FDG-PET images. (D) GS therapy leads to a significant reduction in infarct size on Day 30 after AMI in histological analyses. (E) Representative Masson's trichrome stainings for GS-treated and placebo animals on Day 30 after AMI. Control group n = 10, treatment group n = 13. All data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s. = not significant.

By analysing the histology, we confirmed significant infarct size reduction on Day 30 after AMI in GS-treated vs. placebo animals (P = 0.03, Figure 1D). Figure 1E shows representative Masson's trichrome stainings illustrating the smaller infarct extent as well as the enhanced wall thickness of the infarct area in GS-treated animals.

Sitagliptin + G-CSF attenuates the cardiac inflammatory response to myocardial infarction

FDG-PET imaging provided serial in vivo information on metabolic processes after AMI. The FDG uptake in ‘percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g)’ is the ratio between the tracer activity detected in the tissue and the total one injected for the PET scan. It provides a semi-quantitative and reliable estimate of glucose uptake. Elevated values of %ID/g are detectable during phases of high metabolic activity, e.g. during inflammatory and growth processes.

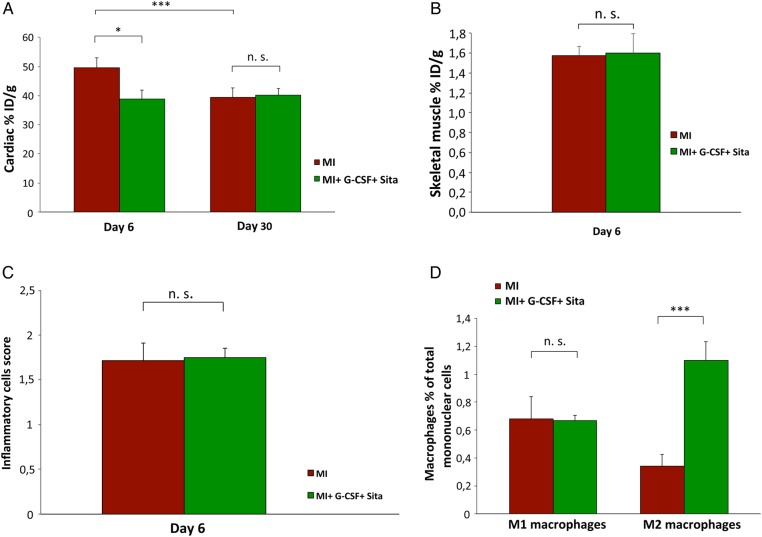

FDG-PET imaging revealed significantly lower cardiac %ID/g values for GS-treated animals on Day 6 after AMI when compared with placebo (39 ± 3 vs. 50 ± 3%, P = 0.037, Figure 2A). Thus, for GS-treated animals, cardiac FDG uptake was significantly lower when compared with placebo animals as early as on Day 6 after AMI. Remarkably, on Day 6 after AMI cardiac FDG uptake in the GS-treated group was already as low as the FDG uptake that placebo animals only showed in the late PET scan on Day 30 after AMI (40 ± 2 and 39 ± 3%, Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Sitagliptin + G-CSF attenuates the cardiac inflammatory response to myocardial infarction. (A) Serial in vivo small-animal FDG-PET scans. The cardiac FDG uptake is significantly lower in GS-treated animals on Day 6 after AMI (P = 0.037). Control group n = 10, treatment group n = 13. ID, injected dose. (B) Skeletal muscle %ID/g values do not differ between GS-treatment and control group on Day 6 after AMI (P = 0.918). Control group n = 10, treatment group n = 13. ID, injected dose. (C) No difference in the histopathological inflammatory cells score between GS-treatment and placebo group (P = 0.90). Both groups n = 12. (D) Cardiac flow cytometry on Day 6 after AMI showing a significant increase in anti-inflammatory M2- (F4-80+/CD206+) macrophage subpopulations within the hearts of GS-treated animals (P < 0.001). No difference in M1-(F4-80+/Gr-1+) macrophage subpopulations (P = 0.96). Both groups n = 9. All data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s. = not significant.

We aimed to confirm that these findings are actually driven by GS-induced differences in the cardiac inflammatory response to AMI between the groups instead of by merely Sitagliptin-induced general alterations in tracer uptake for the treatment group.

Skeletal muscle %ID/g values were determined as well for treatment and placebo groups. In contrast to the cardiac values, skeletal muscle %ID/g values did not differ between the two groups (P = 0.918, Figure 2B). These results verify that there is no general Sitagliptin-induced alteration in tracer uptake in treated mice, but that the detected cardiac %ID/g differences between the groups indeed represent a GS treatment induced significant attenuation of cardiac metabolic activity in treated animals.

To further substantiate the impact of GS-treatment on the cardiac inflammatory response to myocardial infarction, histology for inflammatory cells was performed and the histopathological inflammatory cells score was subsequently calculated. As expected, there was no difference in the general inflammatory cells score between the groups (1.71 ± 0.14 vs. 1.75 ± 0.22; P = 0.90; Figure 2C). Recent findings from a study of diabetic patients,17 and the latest results from our atherosclerosis mouse model study18 found that DPP-IV inhibition by Sitagliptin exerts a substantial anti-inflammatory effect, which is not based on numerical differences between inflammatory cells migrating into the tissue but is largely based on priming monocytes from pro-inflammatory (M1, F4-80+/Gr-1+) to anti-inflammatory (M2, F4-80+/CD206+) macrophage phenotypes.17,18 To further investigate the protective effect of GS treatment on the inflammatory response to AMI in infarcted mice with regard to the possible mode of action, we performed cardiac flow cytometry for F4-80, Gr-1, and CD206. Remarkably, cardiac flow cytometry revealed a significant increase in anti-inflammatory M2- (F4-80+/CD206+) macrophage subpopulations within the hearts of GS-treated animals (1.1 ± 0.1 vs. 0.3 ± 0.1, P < 0.001; Figure 2D). This finding most likely represents a key mechanism for the suggested protective attenuation of post-infarct inflammatory processes in GS-treated mice seen in this study.

Sitagliptin + G-CSF reduces adverse cardiac remodelling

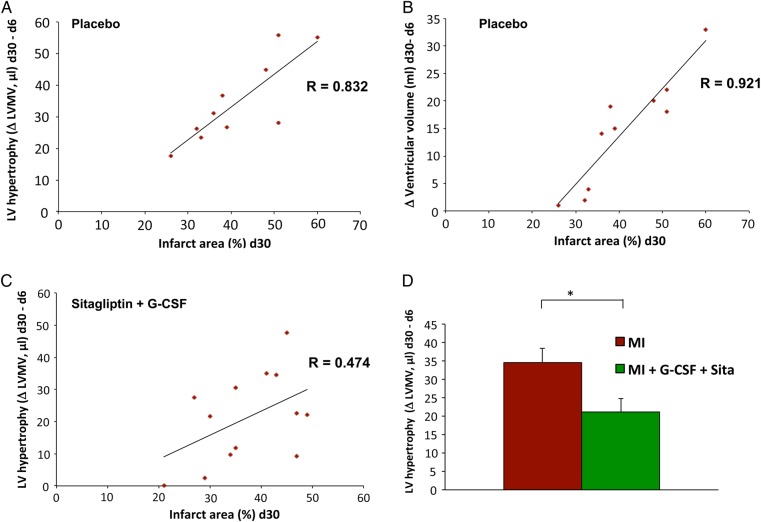

In order to evaluate the impact of GS treatment on adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI, we measured the myocardial hypertrophy (PET LVMV) of the non-infarcted myocardium at different stages following AMI. For placebo-treated animals, there was a strong positive correlation between infarct size and left ventricular hypertrophy from Day 6 to Day 30, illustrating that there is normally a compensatory response of myocardial hypertrophy as part of the adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI (R = 0.832; Figure 3A). In addition, the left ventricular volume was serially measured to detect left ventricular dilatation during adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI. There is also a highly positive correlation between infarct size and an increase in left ventricular volume from Day 6 to Day 30 in placebo animals, illustrating left ventricular dilatation as a critical component of adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI (R = 0.921; Figure 3B). On the other hand, in GS-treated mice, the correlation between infarct size and left ventricular hypertrophy is much weaker (R = 0.474; Figure 3C). That is to say, the unfavourable myocardial hypertrophy is significantly reduced in GS-treated animals when compared with placebo animals (P = 0.030, Figure 3D). We found similar protective impacts on left ventricular dilatation among GS-treated animals (data not shown). These findings strongly indicate that GS treatment significantly attenuates adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI.

Figure 3.

Sitagliptin + G-CSF reduces adverse cardiac remodelling. (A) Strong positive correlation between infarct size and left ventricular hypertrophy from Day 6 to Day 30 after AMI in placebo animals illustrating the normal compensatory myocardial hypertrophy as part of adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI (R = 0.832). (B) Strong positive correlation between infarct size and left ventricular volume increase from Day 6 to Day 30 in placebo animals, depicting left ventricular dilatation as an important part of adverse cardiac remodelling after AMI (R = 0.921). (C) Weaker correlation between infarct size and left ventricular hypertrophy from Day 6 to Day 30 in GS-treated animals (R = 0.474). (D) In GS-treated mice, myocardial hypertrophy related to adverse remodelling is significantly reduced when compared with placebo animals (P = 0.030). Treatment group n = 13, control group n = 12. All data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s. = not significant.

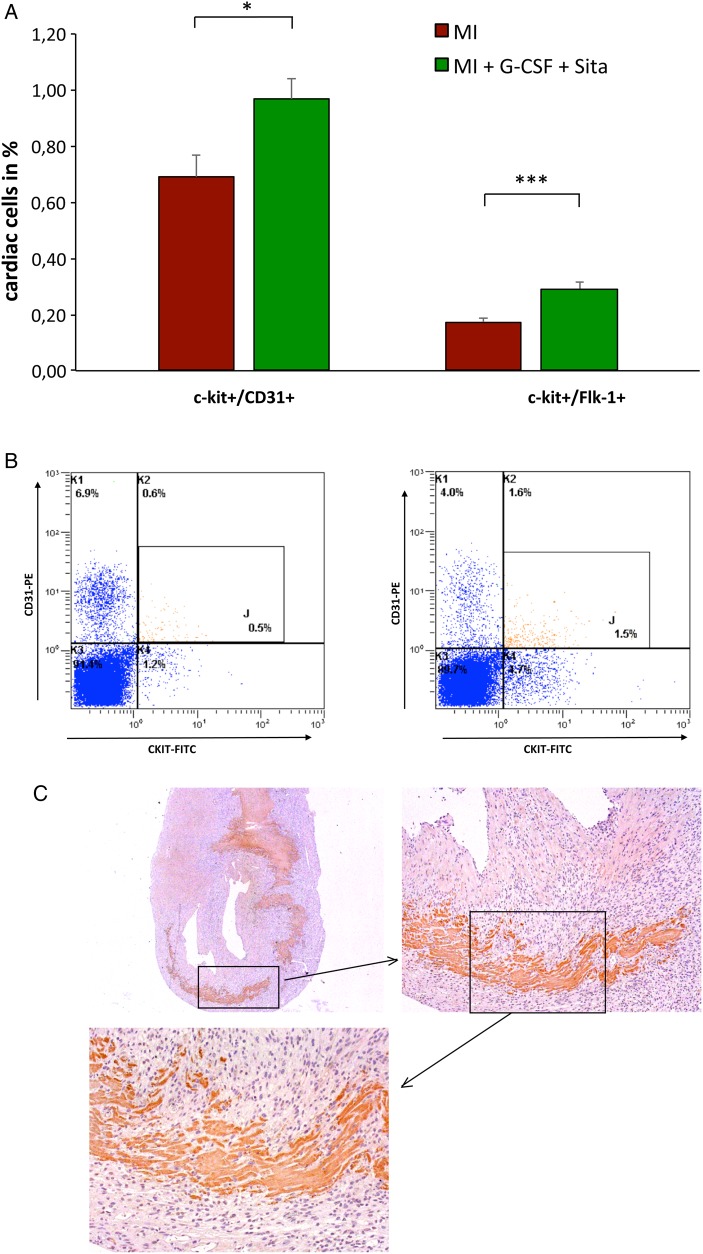

Increase in cardiac c-kit positive cells

Flow cytometry of non-myocyte cardiac cells showed a significant increase in c-kit positive cells following therapy with G-CSF and Sitagliptin. GS treatment triggered significant augmentation of both c-kit+/CD31+ (P = 0.02, Figure 4A and B) and c-kit+/Flk-1+ cardiac subpopulations (P = 0.0004, Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Increase in cardiac c-kit positive cells. (A) Significant increase in both c-kit+/CD31+ (P = 0.02) and c-kit+/Flk-1+ (P = 0.0004) cardiac subpopulations following GS treatment in cardiac flow cytometry on Day 6 after AMI; n = 12 in both groups. (B) Representative FACS images of c-kit+/CD31+ cells for control group (left) and GS-treatment group (right). (C) Representative immunohistochemistry for c-kit+ in GS-treated animals. All data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s. = not significant.

Immunohistochemistry for c-kit in GS-treated animals revealed an induction of c-kit expression in endogenous heart cells including cardiomyocytes and an increase of c-kit positive progenitor cells within the myocardium (Figure 4C).

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence on the mechanisms through which treatment with G-CSF and Sitagliptin improves cardiac regeneration and reduces adverse remodelling after AMI.

This innovative design using small-animal functional FDG-PET—rather than the experimental techniques commonly used in the field—allowed for reliable non-invasive, high-resolution, serial in vivo studies, which enabled us to investigate the therapeutic effects of GS treatment on cardiac regeneration. Furthermore, using FDG-PET provided us with standardized in vivo information on metabolic processes, which in turn provided important insights on the mechanisms and mode of action of this new therapeutic approach. Our results suggest that GS treatment significantly reduces the cardiac inflammatory response to myocardial infarction and attenuates adverse cardiac remodelling. In addition, GS treatment reduces the infarct size after AMI compared with placebo treatment. Furthermore, our results indicate that GS treatment following AMI enhances myocardial recovery after AMI via an increased recruitment of circulating c-kit expressing cells as well as via induction of myocardial c-kit expression. In-depth mechanistic analyses performed recently have shown that after myocardial injury cardiac c-kit is highly expressed by local endogenous cardiac stem cells that further contribute to myocardial regeneration.19

This study shows that GS treatment leads to a modest, but significant reduction in infarct size after AMI. Serial PET scans performed on the same animal revealed that this reduction takes place between Day 6 and Day 30 after AMI. Histology on Day 30 after AMI confirmed a significant reduction in infarct size for GS-treated animals compared with placebo animals. Similarly, GS therapy leads to a significant improvement in left ventricular function, cardiac output, and survival rates, a result that has been previously demonstrated by our group.7

Myocardial infarction causes an inflammatory response with associated secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the injured myocardium. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that accentuation, prolongation, or expansion of the post-infarction inflammatory response results in worse outcome and cardiac dysfunction following myocardial infarction.20 Even myocardium that is remote to the infarct area is affected by inflammatory processes to a great extent, providing the basis for adverse left ventricular remodelling.21 In PET imaging, the cardiac FDG uptake as %ID/g provides a semi-quantitative and reliable estimate of glucose uptake and thereby is a possible indicator of inflammatory processes within particular organs or tissue types.

FDG uptake to the myocardium is glucose mediated. Of note, DPP-IV-inhibition by Sitagliptin not only stabilizes SDF-1α but also GLP-1. Therefore, it is fundamental to rule out the possibility that Sitagliptin-induced general alterations in glucose metabolism and transportation may be the real triggers of any detected differences in %ID/g values between treated and untreated animals instead of differences in the cardiac metabolic activity between the groups. 18F-FDG is a glucose analogue, which is transported into cells through glucose membrane transporters and subsequently phosphorylated by hexokinase to 18F-FDG-6-phosphate. Cardiac and skeletal muscle feature the same set of glucose transporters: the main insulin-regulated glucose transporter expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle and adipose tissue is GLUT 422,23; GLUT 12 is an additional transporter expressed in both cardiac and skeletal muscle.24 To rule out that any detected differences regarding cardiac %ID/g could be due to general Sitagliptin-induced alterations in tracer uptake instead of GS-induced differences in cardiac metabolic activity, skeletal muscle %ID/g values were determined for treatment and placebo group. There was no difference regarding skeletal muscle %ID/g values between the two groups. On the contrary, cardiac FDG uptake was significantly lower for GS-treated mice when compared with placebo mice as early as on Day 6 after AMI.

GS- and placebo-treated animals both recovered to the same level of cardiac %ID/g values within a time span of 30 days after AMI. Remarkably, on Day 6, after AMI cardiac FDG uptake in the GS-treated group was already as low as the FDG uptake that placebo animals only showed in the late PET scan on Day 30 after AMI, whereas placebo animals displayed significantly elevated values on Day 6 after AMI (Figure 2A). These findings further substantiate that for GS-treated animals inflammatory processes in myocardial infarction21,25,26 seem to be significantly attenuated.

There is extensive evidence demonstrating the abundance of macrophages in the infarcted heart and their potential to regulate the inflammatory response. In the environment of the healing heart, upregulation of macrophage-colony stimulating factor induces monocyte to macrophage differentiation.27 The key for the role of macrophages in cardiac repair lies in alterations in phenotype and function of macrophage subpopulations. In general, two distinct macrophage subsets have been recognized: the classically activated M1 macrophages that exhibit enhanced microbicidal capacity and secrete large amounts of pro-inflammatory mediators and the alternatively activated anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages that show increased phagocytic activity.20,28,29

Two years ago, evidence first emerged that DPP-IV inhibition by Sitagliptin leads to a favourable shift from pro-inflammatory M1- to anti-inflammatory M2-macrophage subpopulations in diabetic patients and also reduces inflammatory cytokines.17 Just very recently, our group provided evidence using an atherosclerosis mouse model that DPP-4 inhibition primes monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages via the SDF-1/CXCR4 signalling pathway and that this effect most likely leads to the protective impact of DPP-IV inhibition on atherosclerosis.18 Of note, Satomi et al. investigated intracellular FDG accumulation in M1 and M2 polarized macrophages. The authors differentiated THP-1 macrophages into M1 and M2 polarized macrophages and investigated their 3H-labelled FDG uptake under optimal glucose conditions. Remarkably and in line with our findings, the authors found that M2 polarization, compared with M1 polarization, results in decreased intracellular accumulation of FDG.30 The mechanisms include up/downregulation of GLUT-1, GLUT-3, hexokinase 1, hexokinase 2, and G6Pase. In our actual work, we provide evidence in a mouse model of myocardial infarction that there is a significant increase in anti-inflammatory M2-macrophages in the hearts of GS-treated animals after AMI, most likely representing a key mechanism for the lower cardiac FDG uptake in GS-treated mice when compared with the control group, suggesting attenuated inflammatory response after AMI following GS treatment.

Supporting our findings, a recent study by Lee et al. revealed a high FDG uptake in mice on Day 5 after AMI. Cell depletion and isolation data, fluorescence-activated cell sorting, polymerase chain reaction, and histology, confirmed that this elevated FDG uptake mostly reflected inflammation, and it was suggested that post-AMI myocardial inflammation represents the main trigger for post-ischaemic adverse cardiac remodelling.26 In line with the results of Lee et al., recent data suggest that DPP-IV inhibitors play an effective role in the suppression of pro-inflammatory states: Sitagliptin leads to a significant reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, endotoxin receptor, TLR-4, TLR-2, nuclear factor-kB of C-reactive protein, and IL-6 concentrations.31

There is growing evidence suggesting that prolongation and accentuation of the post-infarction inflammatory response results in marked adverse remodelling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Thus, strategies for enhancing inhibitory and pro-resolving signals in the infarcted heart are of high therapeutic relevance. Defective suppression and impaired resolution of inflammation may be important mechanisms in the pathogenesis of adverse remodelling and in progression to heart failure.20

The molecular and cellular changes in the remodelling heart after AMI affect both the area of necrosis and the non-infarcted segments of the ventricle and these changes manifest clinically as increased chamber dilation and myocardial hypertrophy.32 The extent of post-infarction remodelling is dependent on the size of infarction and on the quality of cardiac repair.33,34 For placebo-treated animals, a strong positive correlation between infarct size and unfavourable compensatory myocardial hypertrophy as a part of post-infarct adverse remodelling exists in our study. In parallel with this result, there is also a strong correlation between infarct size and left ventricular dilatation for control mice. Remarkably, both myocardial hypertrophy and chamber dilatation as the cornerstones of adverse cardiac remodelling are reduced in GS-treated animals. Suppression of inflammatory processes after myocardial infarction by DPP-IV inhibition on the one hand and reduction of infarct size by effective BMPC-induced repair mechanisms on the other hand most likely lead to the significant attenuation of adverse cardiac remodelling shown in our study.

Regarding the therapeutic effect of GS therapy on a cellular basis, our study reveals that GS treatment leads to a significant increase in myocardial c-kit expressing cells. There is evidence that the adult myocardium harbours endogenous c-kit positive cardiac stem cells, which are necessary and sufficient for the regeneration and repair of myocardial damage.35,36 Recently, van Berlo et al.37 demonstrated that endogenous c-kit positive cells contribute cardiomyocytes to the heart though this effect is minimal. Several studies suggest that while there is an activation of c-kit expression within resident cells of the heart following infarction, this induction is overwhelmingly associated with neovasculogenesis.38 In line with this, GS treatment leads to significantly enhanced neovasculogenesis, as we have shown before by CD 31+ immunostaining.7 In the actual study, we revealed a significant increase in c-kit+/Flk-1+ and c-kit+/CD31+ cells within the hearts of treated animals, consistent with endogenous resident cardiac stem cells. Thus, besides effective BMPC-induced repair mechanisms, as we have shown before,5–7 and the probable reduction of the inflammatory response after AMI shown above, GS therapy on a cellular basis also significantly increases the fraction of endogenous myocardial c-kit expressing cells, which is known to be necessary and sufficient for the regeneration and repair of myocardial damage.

Conclusion

Featuring small-animal FDG-PET as an innovative method that allows reliable non-invasive, high-resolution, serial in vivo studies and uniquely provides information on metabolic processes in mice, this study provides mechanistic evidence that dual therapy comprising G-CSF and Sitagliptin improves cardiac regeneration after AMI and significantly reduces post-infarct adverse remodelling. Furthermore, our results suggest that GS-treatment significantly reduces the cardiac inflammatory response associated with myocardial infarction. Of note, our study shows that there is a significant increase in anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage subpopulations following GS therapy. Furthermore, this study provides evidence that GS treatment significantly increases the fraction of myocardial c-kit expressing cells, which is known to be necessary and sufficient for the regeneration and repair of myocardial damage.

Study limitations

Sitagliptin was adapted to mouse metabolism as proved by previous mass spectrometry analyses and applied in higher dosages than they are used in humans.7

In this study, we obtained three-dimensional PET recordings in list mode during the interval of 30–45 min after tracer injection. Future studies might consider dynamic PET acquisitions to provide additional interesting information on myocardial glucose metabolism by means of Patlak analysis. Furthermore, applying suppression techniques to reduce the remote myocardial signal to allow visualization of the infarct territory FDG uptake might add interesting insights into the topic of post-infarct inflammatory processes and should be investigated in future studies. Also, adding additional scanning timepoints within the first 5 days after AMI might contribute useful information on peak inflammation in future studies.

As a limitation, the authors cannot fully preclude the possibility that the differences in cardiac %ID/g values between the groups may also be influenced by differences in the level of cardiomyocyte metabolism. Nevertheless, reduced myocardial FDG uptake due to less strain-influenced glucose uptake in GS-treated animals would be another aspect in favour of the positive impact of GS therapy on cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction.

Funding

This work was supported by the FoeFoLe-programme of the Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich.

Conflict of interest: The Ludwig Maximilian University has filed the patent ‘Use of G-CSF for Treating Ischemia’ (EP 03 02 4526.0 and US 60/514,474). W.-M.F. receives a speaker honorarium from MSD. All other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

A part of this work originated from the doctoral thesis of Lisa Paintmayer. We are grateful to Judith Arcifa for her excellent technical assistance. The authors would like to thank Jenaleen Law for proof reading the manuscript.

References

- 1.Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature 2004;428:668–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazel S, Cimini M, Chen L, Li S, Angoulvant D, Fedak P, et al. Cardioprotective c-kit+ cells are from the bone marrow and regulate the myocardial balance of angiogenic cytokines. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1865–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Rubart M, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature 2004;428:664–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaruba MM, Huber BC, Brunner S, Deindl E, David R, Fischer R, et al. Parathyroid hormone treatment after myocardial infarction promotes cardiac repair by enhanced neovascularization and cell survival. Cardiovasc Res 2008;77:722–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaruba MM, Theiss HD, Vallaster M, Mehl U, Brunner S, David R, et al. Synergy between CD26/DPP-IV inhibition and G-CSF improves cardiac function after acute myocardial infarction. Cell Stem Cell 2009;4:313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theiss HD, Vallaster M, Rischpler C, Krieg L, Zaruba MM, Brunner S, et al. Dual stem cell therapy after myocardial infarction acts specifically by enhanced homing via the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Stem Cell Res 2011;7:244–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theiss HD, Gross L, Vallaster M, David R, Brunner S, Brenner C, et al. Antidiabetic gliptins in combination with G-CSF enhances myocardial function and survival after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:3359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deindl E, Zaruba MM, Brunner S, Huber B, Mehl U, Assmann G, et al. G-CSF administration after myocardial infarction in mice attenuates late ischemic cardiomyopathy by enhanced arteriogenesis. FASEB J 2006;20:956–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theiss HD, Gross L, Vallaster M, David R, Brunner S, Brenner C, et al. Antidiabetic gliptins in combination with G-CSF enhances myocardial function and survival after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:3359–3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunner S, Todica A, Boning G, Nekolla SG, Wildgruber M, Lehner S, et al. Left ventricular functional assessment in murine models of ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy using [18 F]FDG-PET: comparison with cardiac MRI and monitoring erythropoietin therapy. EJNMMI Res 2012;2:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Todica A, Zacherl MJ, Wang H, Boning G, Jansen NL, Wangler C, et al. In-vivo monitoring of erythropoietin treatment after myocardial infarction in mice with [(6)(8)Ga]Annexin A5 and [(1)(8)F]FDG PET. J Nucl Cardiol 2014;21:1191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slomka PJ, Dey D, Przetak C, Aladl UE, Baum RP. Automated 3-dimensional registration of stand-alone (18)F-FDG whole-body PET with CT. J Nucl Med 2003;44:1156–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehner S, Sussebach C, Todica A, Uebleis C, Brunner S, Bartenstein P, et al. Influence of SPECT attenuation correction on the quantification of hibernating myocardium as derived from combined myocardial perfusion SPECT and (1)(8)F-FDG PET. J Nucl Cardiol 2014;21:578–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croteau E, Benard F, Cadorette J, Gauthier ME, Aliaga A, Bentourkia M, et al. Quantitative gated PET for the assessment of left ventricular function in small animals. J Nucl Med 2003;44:1655–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todica A, Brunner S, Boning G, Lehner S, Nekolla SG, Wildgruber M, et al. [68Ga]-albumin-PET in the monitoring of left ventricular function in murine models of ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy: comparison with cardiac MRI. Mol Imaging Biol 2013;15:441–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou YY, Wang SQ, Zhu WZ, Chruscinski A, Kobilka BK, Ziman B, et al. Culture and adenoviral infection of adult mouse cardiac myocytes: methods for cellular genetic physiology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000;279:H429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satoh-Asahara N, Sasaki Y, Wada H, Tochiya M, Iguchi A, Nakagawachi R, et al. A dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, exerts anti-inflammatory effects in type 2 diabetic patients. Metabolism 2013;62:347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner C, Franz W, Kühlenthal S, Kuschnerus K, Remm F, Gross L, et al. DPP-4 inhibition ameliorates atherosclerosis by priming monocytes into M2 macrophages. Int J Cardiol 2015;199:163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadal-Ginard B, Ellison GM, Torella D. The cardiac stem cell compartment is indispensable for myocardial cell homeostasis, repair and regeneration in the adult. Stem Cell Res 2014;13(3 Pt B):615–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res 2012;110:159–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruparelia N, Digby JE, Jefferson A, Medway DJ, Neubauer S, Lygate CA, et al. Myocardial infarction causes inflammation and leukocyte recruitment at remote sites in the myocardium and in the renal glomerulus. Inflamm Res 2013;62:515–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheepers A, Joost HG, Schurmann A. The glucose transporter families SGLT and GLUT: molecular basis of normal and aberrant function. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2004;28:364–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brosius FC, III, Liu Y, Nguyen N, Sun D, Bartlett J, Schwaiger M. Persistent myocardial ischemia increases GLUT1 glucose transporter expression in both ischemic and non-ischemic heart regions. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1997;29:1675–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimenez-Amilburu V, Jong-Raadsen S, Bakkers J, Spaink HP, Marin-Juez R. GLUT12 deficiency during early development results in heart failure and a diabetic phenotype in zebrafish. J Endocrinol 2015;224:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frantz S, Nahrendorf M. Cardiac macrophages and their role in ischaemic heart disease. Cardiovasc Res 2014;102:240–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WW, Marinelli B, van der Laan AM, Sena BF, Gorbatov R, Leuschner F, et al. PET/MRI of inflammation in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frangogiannis NG, Mendoza LH, Ren G, Akrivakis S, Jackson PL, Michael LH, et al. MCSF expression is induced in healing myocardial infarcts and may regulate monocyte and endothelial cell phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003;285:H483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol 2002;23:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol 2010;11:889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satomi T, Ogawa M, Mori I, Ishino S, Kubo K, Magata Y, et al. Comparison of contrast agents for atherosclerosis imaging using cultured macrophages: FDG versus ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide. J Nucl Med 2013;54:999–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makdissi A, Ghanim H, Vora M, Green K, Abuaysheh S, Chaudhuri A, et al. Sitagliptin exerts an antinflammatory action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:3333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:569–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frangogiannis NG. The immune system and cardiac repair. Pharmacol Res 2008;58:88–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan W, Duffy SJ, White DA, Gao XM, Du XJ, Ellims AH, et al. Acute left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: coupling of regional healing with remote extracellular matrix expansion. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:884–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellison GM, Vicinanza C, Smith AJ, Aquila I, Leone A, Waring CD, et al. Adult c-kit(pos) cardiac stem cells are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair. Cell 2013;154:827–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbanek K, Torella D, Sheikh F, De Angelis A, Nurzynska D, Silvestri F, et al. Myocardial regeneration by activation of multipotent cardiac stem cells in ischemic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:8692–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Berlo JH, Kanisicak O, Maillet M, Vagnozzi RJ, Karch J, Lin SC, et al. c-kit+ cells minimally contribute cardiomyocytes to the heart. Nature 2014;509:337–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jesty SA, Steffey MA, Lee FK, Breitbach M, Hesse M, Reining S, et al. c-kit+ precursors support postinfarction myogenesis in the neonatal, but not adult, heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:13380–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]