Abstract

Feasibly implemented Web-based smoking media literacy (SML) programs have been associated with improving SML skills among adolescents. However, prior evaluations have generally had weak experimental designs. We aimed to examine program efficacy using a more rigorous crossover design. Seventy-two ninth grade students completed a Web-based SML program based on health behavior theory and implemented using a two-group two-period crossover design. Students were randomly assigned by classroom to receive media literacy or control interventions in different sequences. They were assessed three times, at baseline (T0), an initial follow-up after the first intervention (T1) and a second follow-up after the second intervention (T2). Crossover analysis using analysis of variance demonstrated significant intervention coefficients, indicating that the SML condition was superior to control for the primary outcome of total SML (F = 11.99; P < 0.001) and for seven of the nine individual SML items. Results were consistent in sensitivity analyses conducted using non-parametric methods. There were changes in some exploratory theory-based outcomes including attitudes and normative beliefs but not others. In conclusion, while strength of the design of this study supports and extends prior findings around effectiveness of SML programs, influences on theory-based mediators of smoking should be further explored.

Introduction

Although adolescent smoking has declined overall in the past two decades [1] this decline is now slowing substantially [2, 3]. It is estimated that 41% of US high school students have ever tried cigarette smoking, 15% are current smokers and 9% have smoked a whole cigarette before age 13 [1]. Consequently, tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States [4]. Because 90% of all adult smokers begin smoking by their teens—with two-thirds becoming daily smokers before the age of 19 [4]—feasible and effective prevention programs that target adolescent smoking are urgently needed.

Cigarette smoking initiation and maintenance among young people is multi-factorial. Prior research has identified multiple socio-demographic, intrinsic and environmental risk and protective factors [4–6]. Media exposures have also been associated with adolescent cigarette smoking. An average 8–18-year old in the United States is exposed to 8–10 hours of media—even outside school [7]—which makes adolescents vulnerable to tobacco-related content associated with negative smoking outcomes [8]. For example, viewing more depictions of tobacco use in movies is associated with cigarette smoking initiation [9, 10] and established smoking [11, 12]. Similarly, personal identification with an on-screen smoking protagonist predicts increased intention to smoke among both adolescent non-smokers [13] and established smokers [14]. Exposure to depictions of tobacco use on social media is also associated with adolescent smoking [15, 16]. In sum, the magnitude of media exposure on adolescent cigarette smoking may be equal to or even greater than traditional risk factors, such as sensation seeking and peer smoking [11].

To address this influence of media portrayals on tobacco use, innovative prevention programming has incorporated media literacy, which aims to improve a participant’s ability to analyze and evaluate media messages in a broad range of forms [17]. It provides a framework in which adolescents become discerning consumers of media and feel empowered to make choices from a more informed perspective [18]. Organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Office of National Drug Control Policy endorse the use of media literacy for prevention of harmful health behaviors [8, 19]. However, while media literacy programs are frequently used to address adolescent health risks such as eating disorders and body image [20], there are fewer data regarding smoking-related media literacy (SML). For example, in a comprehensive systematic review of media literacy programming, only 3 of 23 studies related to tobacco use [21], despite its substantial contribution to world morbidity and mortality [4].

Although some studies have suggested SML education improves critical assessment of tobacco-related messages, many of these studies have been limited in terms of methodology. For example, school-based tobacco prevention programs in Washington state and Missouri suggest that SML can be taught [22, 23]. However, evaluations have relied upon a pre–post-test design with no comparison group. When there is no control group, it is unclear whether the participants’ outcome measures improved directly as a result of the intervention—or whether it may have been because of other factors such as the passage of time.

Two studies used a more robust design—a randomized-controlled trial—allowing for intervention versus control comparisons [24, 25]. The first study provided evidence that, in a classroom setting, media literacy programming was effective in decreasing intention to use tobacco and alcohol in the future [25]. The second study indicated that SML was feasible and effectively taught in the classroom setting [24]. However, both of these studies used an intensive multi-modal facilitator-led program. Although these results are valuable, such programs may present barriers to sustainability in terms of cost, training and standardization.

Subsequently, a related Web-based program was developed to alleviate these sustainability issues [26]. Results from this initial study were encouraging in terms of ability of the program to increase SML. However, this study relied upon a simple pre–post-test test design rather than a more rigorous methodology, limiting generalizability and ability to make causal inferences.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine a Web-based SML program using a more rigorous design. Crossover designs, primarily used in pharmacologic research, are a statistically robust and novel approach to this type of research and have several advantages [27]. First, they require fewer participants than other designs such as pre–post-test or randomized-control trials, making them more statistically efficient [27]. Second, each participant serves as his/her own control, reducing within-subject variability [28]. Third, analysis of crossover studies can include a test for period effects, a common source of bias [29, 30].

Our primary aim was to determine if the curriculum was effective in increasing total SML (Aim 1). Our exploratory aims were to determine if exposure to the intervention was associated with changes in mediators of smoking according to an established conceptual framework on which the program was based, including smoking attitudes (Aim 2) and perceived normative beliefs (Aim 3). We hypothesized that after completing the curriculum, students would demonstrate increased total SML scores (Hypothesis 1). We also expected that exposure to the intervention would be associated with reduced positive attitudes about smoking (Hypothesis 2), and a diminished sense of positive smoking normative beliefs (Hypothesis 3).

Methods

Design

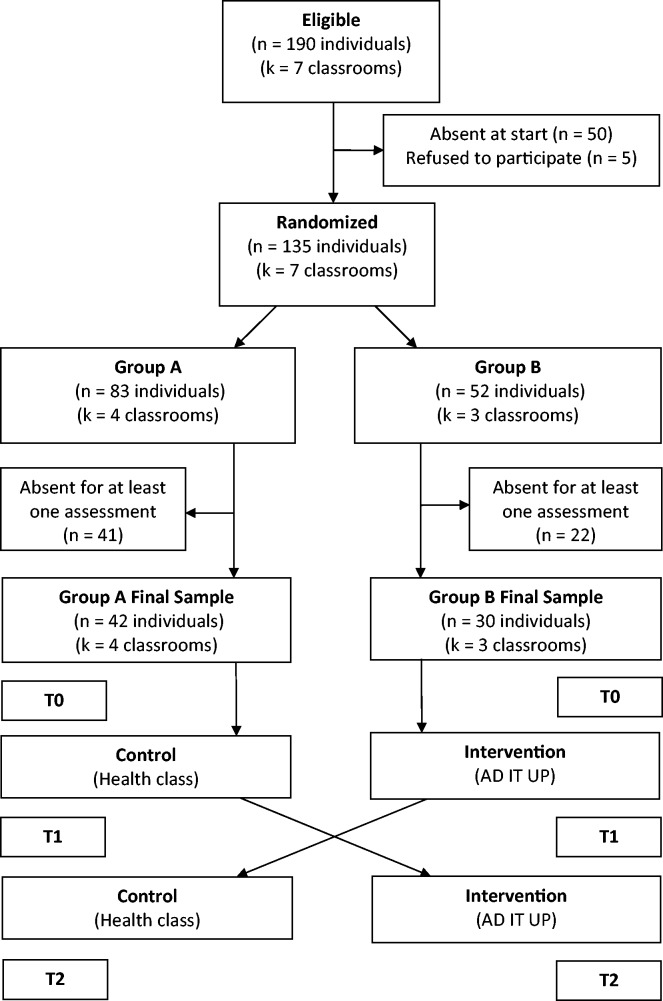

We conducted a crossover study of a Web-based SML program that evolved from a previous pilot version of a similar curriculum [26]. Data collection was implemented in collaboration with high school teachers and research staff in 2012. A two-group two-period crossover design was used to assess the effect of the intervention. All students received the curriculum and were assessed on 3 different occasions (T0, T1 and T2). Students were randomly assigned to one of two groups (A or B). The time between baseline (T0) and T1 was defined as Period 1 and the time between T1 and T2 was defined as Period 2. Students assigned to Group A were given regular coursework (control) during Period 1 and the intervention during Period 2, whereas Group B received the intervention during Period 1 and regular coursework (control) during Period 2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

As is indicated in the flow diagram, 135 from the initially 190 eligible students were randomized to either Group A or Group B. The final sample consisted of 72 individuals, 42 of whom were from Group A in 4 classrooms and 30 of whom were in Group B in 3 classrooms. T0, T1 and T2 represent the baseline, initial follow-up and final follow-up data collections.

Setting and participants

Our study was conducted at an urban public high school just outside of [redacted for blind review]. Approval for the project was granted by the superintendent of the school district and the [redacted for blind review] Institutional Review Board (IRB no. [redacted for blind review]). At the time of data collection the school had an enrollment of about 1380 students in 9th through 12th grades. The student population was 52% Caucasian, and the remaining 48% were predominantly African American or of mixed race. Nearly three-fourths (72%) of students received free or reduced-cost school lunch. Our eligible study population consisted of a convenience sample of seven classrooms that contained a total of 190 enrolled ninth grade students. The seven specific classrooms were selected based purely on convenience of time of day for teachers and research staff; teachers stated that none of the classrooms was different from others in ability level or tracking.

Procedures

Opt-out consent letters were sent via mail to parents and guardians of eligible students. This letter described the study, explained participant rights and provided instructions for withdrawing from the program if parents or students elected not to participate. Of the 190 eligible participants, 135 were randomly assigned to 2 groups: 83 individuals from 4 classrooms to Group A and 52 individuals from 3 classrooms to Group B (Fig. 1). Random assignment was made using a random number generator within Stata statistical software. The implementation occurred over four 45-min class periods, each separated by 1 week. These sessions were embedded within the regular ninth-grade health class curriculum required of all students. Students worked individually in the computer laboratory of the high school. To ensure confidentiality, students created personal logins and passwords to access the Web-based curriculum. Names were not collected, and personal identifiers were not linked to the data. Students were encouraged to work at their own pace. Seventy-two students (53%) were able to complete the entire curriculum and all three assessments. Students who completed the curriculum were given an aluminum water bottle as compensation.

Intervention

AD IT UP is a theory-based anti-smoking media literacy (SML) program developed with foundation grant funding [31, 32]. The Web-based AD IT UP program was derived from the facilitator-led curriculum of the same name [24, 26]. The program is designed to teach youth to think critically about media messages, focusing on messages involving tobacco use. Each letter of AD IT UP represents one of the six key lessons and questions in the curriculum. Each of the lessons also corresponds to a core domain in the conceptual model adapted from the National Association of Media Literacy’s Core Principles of Media Literacy Education document [33]. The Web-based adaptation of the in-person program is described in detail elsewhere [24, 26]. In brief, however, the current intervention expands upon the original programming to include interactive Web-based games designed to enhance in-depth individual learning. For example, the original program included an extended group discussion of different techniques— such as lighting, camera angle, color and props—that are used to alter images in advertisements. In the interactive version, however, participants use an interactive console to manipulate an on-screen image using these various production techniques.

The program was designed for a target audience of ninth grade students for two reasons. First, at this age participants generally have the cognitive skills of abstract thought valuable for understanding and applying the media literacy concepts we wished to impart [34]. Second, because cigarette smoking uptake and maintenance dramatically increase after ninth grade [35], intervening at this time could have strong potential for reducing smoking initiation and/or maintenance. Furthermore, the program was designed to be appealing to African Americans and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) because these populations bear the greatest burden of morbidity and mortality from tobacco use [4]. Previously published work details specific ways in which the curriculum was targeted to these audiences [24, 26, 32], such as featuring African American actors and characters and focusing on tobacco brands commonly marketed to African American and lower SES individuals.

Survey instruments

Demographic data and other relevant student characteristics

We assessed socio-demographic factors including age, sex, race and maternal education as a proxy for SES. Based on the distribution of prior data collected from this population, race was collapsed into three mutually-exclusive categories (Caucasian, African American and Other), and maternal education was grouped as (i) did not graduate from high school, (ii) graduated from high school but not college and (iii) obtained a college degree or higher. We also asked students to self-report grades, and these data were collapsed into two categories: ‘A’s and B’s’ and ‘Lower than B’s’. Finally, students were asked about parents’, siblings’ and friends’ smoking behaviors, which have been shown to be linked to smoking and mediators of smoking [6, 36].

Smoking media literacy

We assessed SML with 9 items modified from a validated 18-item scale [31, 32] with the goal of capturing comprehensive information about SML while decreasing respondent burden. Items were based on the National Association of Media Literacy’s Core Principles of Media Literacy Education [33]. To capture maximal variation, all SML measures were measured with 10-level Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

Attitudes and normative beliefs

We also assessed two important mediators of adolescent smoking according to previous empiric research [36] and the conceptual framework of the Theory of Reasoned Action, which is commonly used in relation to adolescent smoking [37]. Smoking attitudes were measured with 7 items based on a validated scale [36] via a 10-level Likert scale indicating agreement or disagreement with statements such as ‘Smoking cigarettes is not as bad for a person’s health as everyone makes it out to be’. Smoking normative beliefs were measured with three items assessed with 10-level Likert scales ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ with statements such as ‘“Cool” people smoke cigarettes more than “uncool” people’ [6].

Data analysis

We tested for differences in baseline characteristics between participating and drop-out students using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Next, we summarized student characteristic information using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, computed means and SDs for continuous variables and assessed between-group differences (for those randomized to Group A versus Group B) using chi-square and t-tests, respectively.

For outcome variables (media literacy, attitudes and normative beliefs) we calculated Cronbach’s alpha to assess internal consistency reliability at each assessment. To determine the effect of our intervention on these outcomes, we calculated change variables (T1 − T0 and T2 − T1) by group and analysed the difference in change in our outcome variables between Group A and Group B using ANOVA, testing for period, treatment and period by treatment interaction effects. These methods of analysis are adopted from those described by Hills and Armitage for a two-group two-period crossover analysis for continuous outcome variables [27].

We used ANOVA as our primary method of analysis because it is generally considered preferable due to it being reasonably insensitive to deviations from the normality assumption [27]. However, we also conducted sensitivity analyses using non-parametric methods in order to examine the robustness of our results. For these sensitivity analyses, we used the Mann-Whitney U test, which is also referred to as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

The statistician was blinded to which group received the intervention first (A or B) until all analyses were complete and tables were created. For all analyses, we defined statistical significance with a two-tailed alpha of 0.05. Data were analysed in 2014 using Stata version 12 [38].

Results

Comparison of those who did and did not complete the program

Chi-square tests and t-tests indicated that there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics (age, sex, race, maternal education, grades and family and peer smoking) between the 72 participants who completed all three assessments and the 63 who did not.

Comparison of those randomized to Group A versus Group B

Socio-demographic factors and other relevant student characteristics are reported in Table I. Chi-square analyses and T-tests indicated that there were no significant differences between Groups A and B (Table I).

Table I.

Baseline student characteristics by group

| Characteristic | Total Sample | Group A | Group B | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 72) | (n = 42) | (n = 30) | ||

| n (column %) | row % | |||

| Age (years) | 0.58 | |||

| ≤15 | 33 (47) | 61 | 39 | |

| >15 | 37 (53) | 54 | 46 | |

| Sex | 0.28 | |||

| Male | 33 (46) | 52 | 48 | |

| Female | 39 (54) | 64 | 36 | |

| Race | 0.16 | |||

| Caucasian | 34 (47) | 62 | 38 | |

| African American | 23 (32) | 43 | 57 | |

| Other | 15 (21) | 73 | 27 | |

| Maternal Education | 0.67 | |||

| Did not graduate high school | 13 (18) | 69 | 31 | |

| Graduated from high school but not college | 21 (29) | 57 | 43 | |

| College degree or higher | 38 (53) | 55 | 45 | |

| Grades | 0.82 | |||

| A’s & B’s | 38 (54) | 58 | 42 | |

| Lower than B’s | 33 (47) | 61 | 39 | |

| Family and Peer Smoking | ||||

| Parental smoking | 0.83 | |||

| Yes | 47 (65) | 57 | 43 | |

| No | 25 (35) | 60 | 40 | |

| Sibling smoking | 0.07 | |||

| Yes | 36 (53) | 47 | 53 | |

| No | 32 (47) | 69 | 31 | |

| Friend smoking | 0.40 | |||

| Yes | 33 (46) | 64 | 36 | |

| No | 39 (54) | 54 | 46 | |

aP values were determined using chi-square analyses, because all variables were categorical.

Outcome variables

Mean values and standard deviations for SML, pro-smoking attitudes and pro-smoking normative beliefs at each time point are presented in Table II. Cronbach’s alpha values indicated adequate internal consistency at all time points for each scale.

Table II.

Description of outcome scale variables at each data collection time point by assignment group

| Outcomea | T0b | αc | T1 | α | T2 | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total SMLa | 0.87 | 0.95 | 0.95 | |||

| Group A | 6.3 (2.0) | 6.2 (2.3) | 7.8 (2.3) | |||

| Group B | 7.0 (1.6) | 7.8 (2.6) | 7.8 (2.5) | |||

| Total Positive Attitudesa | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.79 | |||

| Group A | 2.6 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.7) | |||

| Group B | 2.3 (1.3) | 3.2 (2.1) | 3.2 (1.9) | |||

| Total Positive Normative Beliefs | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |||

| Group A | 3.6 (2.1) | 3.3 (1.9) | 4.0 (2.5) | |||

| Group B | 3.3 (2.2) | 4.0 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.3) |

aEach outcome variable was assessed on a 10-point Likert scale.

bCell values for T0, T1 and T2 represent mean (SD).

cCronbach’s alpha, a measure of internal consistency reliability.

Interpretation of crossover analyses

To confirm or refute specific hypotheses, we tested patterns of outcomes according to time period and group using analysis of variance. In particular, Table III indicates whether there were significant effects for each outcome variable item corresponding to the period, the treatment or the interaction between the period and treatment. For example, when there was a large F-statistic and corresponding low P-value in the ‘Period’ column, this indicated that participant responses tended to systematically change simply whether the difference was tested during Period 1 (between T0 and T1) or Period 2 (between T1 and T2); thus, these variables changed over time regardless of group assignment. However, when there was a large F-statistic and low P-value in the ‘Treatment’ column, this indicates that there was a systematic change in that item only when the participants received the intervention versus control.

Table III.

Results of two-group two-period crossover analysis for media literacy, attitudes, and normative beliefs

| Item | Period |

Treatment |

Interaction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fa | Pa | F | P | F | P | |

| SML items | ||||||

| To make money, tobacco companies would do anything they could get away with. | 1.11 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 3.41 | 0.07 |

| Certain cigarette brands are specially designed to appeal to young children. | 3.99 | 0.05 | 15.5 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.41 |

| Cigarette ads try to link smoking to things that people want like love, beauty and adventure. | 4.90 | 0.03 | 7.72 | 0.006 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| Wearing a shirt with a cigarette logo on it makes a person into a walking advertisement. | 0.13 | 0.72 | 3.21 | 0.08 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| There are often hidden messages in cigarette ads. | 0.15 | 0.70 | 8.42 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| Movie scenes with smoking in them are constructed very carefully. | 0.66 | 0.42 | 5.46 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.79 |

| Cigarette ads show scenes with a healthy feel to make people forget about the health risks. | 0.20 | 0.66 | 5.75 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.81 |

| Most movies and TV shows that show people smoking make it look more attractive than it really is. | 1.70 | 0.20 | 7.56 | 0.007 | 1.52 | 0.22 |

| When you see a smoking ad, it is very important to think about what was left out of the ad. | 0.24 | 0.62 | 6.72 | 0.01 | 0.59 | 0.44 |

| Total SML | 1.82 | 0.18 | 11.99 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.35 |

| Attitude utems | ||||||

| Smoking cigarettes is not as bad for a person’s health as everyone makes it out to be. | 3.75 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.45 |

| Smoking cigarettes at parties is fun. | 3.37 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.39 |

| Smoking helps people deal with problems of stress. | 0.00 | 0.96 | 2.45 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.83 |

| Smoking helps people stay thin. | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.10 | 0.75 |

| Smokers are more fun to be around than nonsmokers. | 9.96 | 0.002 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.75 | 0.39 |

| If someone starts smoking every day, it is very hard for them to stop.b | 0.26 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| Smoking makes a person look more sexy. | 11.16 | 0.001 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| Total positive attitudes | 8.83 | 0.004 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Normative belief items | ||||||

| ‘Cool’ people smoke cigarettes more than ‘uncool’ people. | 0.36 | 0.55 | 1.49 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.84 |

| A wealthy person is more likely to smoke cigarettes than a poor person. | 0.22 | 0.64 | 2.26 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.82 |

| A successful person is more likely to smoke cigarettes than an unsuccessful person. | 0.02 | 0.88 | 8.78 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Total positive normative beliefs | 0.01 | 0.15 | 5.39 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.96 |

aF and P statistics determined using analysis of variance. Bold values indicate P < 0.05.

bThis item was reversed coded during development of composite scale.

Primary outcome of SML

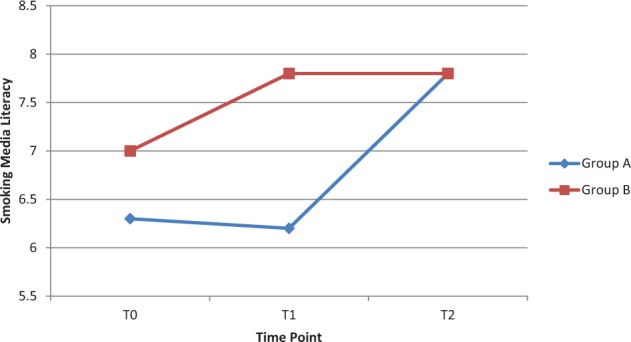

We observed a pattern suggesting increase in total SML scores for Group A during Period 2 and for Group B during Period 1 (Fig. 2). This pattern was significant for a treatment effect, supporting Hypothesis 1. Additionally, there were significant treatment effects for 7 of the 9 media literacy items and slight period effects for two items. However, as indicated by the F and P statistics, the treatment effect for each of these items was stronger than the period effect (Table III).

Fig. 2.

When the blind was lifted, it was revealed that participants in Group A received the control (usual education) between T0 and T1 and the intervention (AD IT UP) between T1 and T2. This figure displays changes in the main outcome of Smoking Media Literacy at each time point by group. Analysis of variance demonstrated that there was a significant effect for intervention (AD IT UP versus control, F = 11.99, P < 0.001).

Exploratory analyses

As reported in Table III, there were no differences between treatment and control with regard to individual attitude items or the total attitude composite score, which refuted Hypothesis 2. However, there were period effects for two items as well as a corresponding period effect for the composite score. Point estimates for these variables indicate that agreement with these items tended to increase over time (regardless of whether intervention or control had just been completed). There was a treatment effect for one normative belief item (Table III). However, importantly, increased agreement with this item tended to be associated with the intervention, which was contrary to Hypothesis 3. Results from non-parametric sensitivity analyses using Mann-Whitney U tests were consistent with ANOVA results for all individual and total outcome variables.

Discussion

Our primary results indicate that the Web-based media literacy program significantly increased SML, supporting Hypothesis 1. However, Hypotheses 2 and 3 were not supported, as the intervention was not associated with a decrease in attitudes or normative beliefs related to cigarette smoking.

This study highlights the value of using a crossover approach in this setting. Some of the methodological rigor of this approach comes from its within- and between-subjects approach, whereby each participant serves as his/ her own control. This enables between-group comparisons while controlling for individual differences that are often an important source of variation. Additionally, this design inherently improves statistical power, requiring fewer participants and making rigorous in-field assessments such as these more feasible [27].

Crossover studies are frequently employed in the pharmacologic milieu. In those studies, it is particularly important to pay attention to possible ‘period effects’ because of the need for a washout period to completely remove the effect of the drug. In our case, however, the use of a model that included period effects enabled us to identify valuable information related to evaluation of health education. For example, participants tended to increasingly agree with certain pro-tobacco sentiments over time, such as ‘Smokers are more fun to be around than nonsmokers’. Because of the study design, we could determine that agreement with such statements increased over time regardless of ordering of intervention and control; this is the type of specificity that a simple pre and post-test study would not be able to achieve.

Another potentially valuable aspect of using the crossover design relates to implementation and evaluation of health education programs in a community-based setting such as a school. In this particular case, we first approached the community partner about conducting a randomized-controlled trial in which only half of the selected classrooms would receive the intervention. Administration was reluctant to offer what they considered a promising intervention to only half of the selected students. Therefore, the crossover design became a compromise in which all students receive the intervention, but we would still be able to obtain rigorous data because of attention to the ordering of intervention and control conditions.

Our findings that exposure to the intervention was associated with measurable and significant improvements in SML were consistent with prior studies which used an in-person intervention [24, 26]. It is valuable to note, however, that this study utilized a Web-based approach, which successfully reduces some of the training, standardization and cost issues involved in facilitator-led programs. Additionally, Web-based programming may be more likely to be replicated in the future and received positively by today’s youth. An intensive process evaluation with qualitative data analysis, outside the scope of this particular study, may be valuable for future similar studies to improve implementations.

Only about 53% of eligible students completed the entire intervention, which required attendance at each of four selected class periods. Because absences are common in urban public schools, a Web-based approach may be valuable so students can complete missed work on their own time. Although for this particular implementation we did not allow for make-up time, it may be valuable to allow for contingency completion plans in future implementations. It is encouraging that all of the drop-out was from absenteeism and not from inability to understand or complete the program.

It is important to note that Hypothesis 2 was not supported, as there were no significant treatment effects for the attitude items. This finding is consistent with both the facilitator-led cluster-randomized trial and pilot pre–post-test studies conducted using AD IT UP [24, 26]. One possible explanation involves a floor effect: positive attitudes regarding smoking were relatively low at baseline and increase in positive attitudes over time could represent regression to the mean or natural developmental change. This could also explain the significant period effect for total attitudes (F = 8.83; P = 0.004).

However, in a broader sense, these results—in conjunction with those of the two studies mentioned earlier—invite reconsideration regarding if and how smoking attitudes are related to SML. In one sense, we should not expect major attitudinal changes, because the media literacy approach specifically tends to avoid strong attitudinal statements or judgments; instead youth are encouraged to develop critical thinking and form their own judgments [17, 18]. However, we do expect that, given increased critical thinking skills, young people will ultimately decrease positive attitudes toward cigarette smoking. Our negative result here could have two possible implications. First, it is possible that our assumption is incorrect, and that media literacy and attitudes may be less related than we believe. Second, it is possible that more time would be required to observe changes in attitudes. It may be that media literacy does not immediately change attitudes, but that experiencing marketing and advertising in the weeks, months or even years following a media literacy experience may translate into reduced positive attitudes toward smoking over time.

Hypothesis 3 was not upheld; in fact, there was a slight paradoxical increase in pro-smoking normative beliefs associated with the intervention. This paradoxical finding is consistent with the pilot pre–post-test study using this media literacy curriculum [24, 26]. The change was very small and driven by only one of the normative beliefs items (‘A successful person is more likely to smoke cigarettes than an unsuccessful person’). One possible explanation for this change may be that the curriculum involves viewing cigarette advertisements. Although this is done with the intention of educating students, it may inadvertently and/or subconsciously alter their beliefs about cigarette smoking in the ways promoters seek. Other possible explanations are similar to those related to the attitude items; in other words, it is possible that normative beliefs toward smoking temporarily and paradoxically improve just after the intervention, but that over time this ‘inoculation’ may actually reduce a participant’s sense of success of smokers.

Limitations

One important limitation of this work is that students were randomized by group but were analyzed as individuals in the ANOVA crossover framework. It is unlikely that this affected results, because individuals worked independently and none of the classrooms was different from others in ability level or tracking. Another limitation is that it is possible there may have been classroom effects on response to the intervention. However, we were unable to assess this due to insufficient power. Additionally, there were no significant differences between those assigned to the two groups (Table I). However, this is still worth noting.

As is common in this type of setting, contamination between randomized groups may have occurred. For example, although students worked individually on computers, they may have discussed classroom materials outside of class. However, it should be noted that contamination would bias the study to the null hypothesis, strengthening the significant results noted.

It is also possible that having different teachers may have influenced students’ experiences with the intervention. However, this is unlikely for two reasons. First, teachers were given identical scripts to read before the intervention, and they had minimal interaction with students during the intervention, which was focused on the Web-based material. Additionally, this is less of a concern in a crossover study, in which participants serve as their own controls instead of being compared with other groups who had different teachers.

It was also an expected limitation that we would not be able to retain all students. Especially in this urban environment with low SES, absenteeism is common. Although we did not find any significant differences between those who completed the programs and those who did not, this does not eliminate the possibility of selection bias.

Finally, the results may not be generalized to other parts of the United States, because the study involved one urban public high school in one region of the country.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study supports prior findings demonstrating effectiveness of SML programs. This study also extends prior findings in that it used a more rigorous methodologic design. The crossover design was valuable in several respects, including that it allowed all students to receive the intervention, which was preferable to the school. Additionally, this was an efficient design that required a relatively small sample size and was still able to isolate effects of the intervention. Future research should further explore potential associations between theory-based mediators of smoking. A more complex analysis such as structural equation modeling may be useful for examining these theory-driven associations.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2014: 1–22. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6dJArgbmk. Accessed: 1 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrazola RA, Dube SR, Engstrom M. Current tobacco use among middle and high school students. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61: 581–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sifferlin A. Teens and tobacco use: why declines in youth have stalled. Time.com 2012. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6dJB5h3hf. Accessed: 1 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking — 50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6dJFmoRUa. Accessed: 1 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, et al. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: an intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics 2009; 123: e274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Primack BA, Switzer GE, Dalton MA. Improving measurement of normative beliefs involving smoking among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161: 434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rideout V, Foehr U, Roberts D. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8–18 Year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6dJDNuqKt. Accessed: 1 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strasburger VC, Hogan MJ. Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 2013; 132: 958–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics 2005; 116: 1183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet 2003; 362: 281–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Primack BA, Longacre MR, Beach ML, et al. Association of established smoking among adolescents with timing of exposure to smoking depicted in movies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 549–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton MA, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Early exposure to movie smoking predicts established smoking by older teens and young adults. Pediatrics 2009; 123: e551–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dal Cin S, Stoolmiller M, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in movies and smoking initiation among black youth. Am J Prev Med 2013; 44: 345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dal Cin S, Gibson B, Zanna MP, et al. Smoking in movies, implicit associations of smoking with the self, and intentions to smoke. Psychol Sci 2007; 18: 559–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, et al. Peer influences: the impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. J Adolesc Heal 2014; 54: 508–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depue JB, Southwell BG, Betzner AE, et al. Encoded exposure to tobacco use in social media predicts subsequent smoking behavior. Am J Heal Promot 2015; 29: 259–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aufderheide P, Firestone C. Media Literacy: A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. Queenstown, MD: Aspen Institute, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobbs R. The seven great debates in the media literacy movement. Am Behav Sci 2004; 48: 42–59. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Designing and Implementing an Effective Tobacco Counter-Marketing Campaign. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2003. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6dJCGMBKb. Accessed: 1 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLean SA, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Mediators of the relationship between media literacy and body dissatisfaction in early adolescent girls: implications for prevention. Body Image 2013; 10: 282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergsma LJ, Carney ME. Effectiveness of health-promoting media literacy education: a systematic review. Health Educ Res 2008; 23: 522–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bier M, Schmidt S, Shields D. School-based smoking prevention with media literacy: a pilot study. J Media Lit Educ 2011; 2: 185–98. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin EW, Pinkleton BE, Hust SJT. Evaluation of an American Legacy Foundation/Washington State Department of Health media literacy pilot study. Health Commun 2005; 18: 75–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Primack BA, Douglas EL, Land SR, et al. Comparison of media literacy and usual education to prevent tobacco use: a cluster randomized trial. J Sch Health 2014; 84: 106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, Austin EW. Media literacy education for elementary school substance use prevention: study of media detective. Pediatrics 2010; 126: 525–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelps-Tschang J, Miller E, Rice KR, et al. Web-based media literacy to prevent tobacco use among high school students. J Media Lit Educ 2015: In press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hills M, Armitage P. The two-period cross-over clinical trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1979; 8: 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland M. Cross-over trials. 2010. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6dJDdOCh7. Accessed: 1 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratkowski D, Evans M, Alldredge J. Cross-over Experiments, Design, Analysis and Application. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones B, Kenward M. Design and Analysis of Cross-Over Trials. London: Chapman and Hall, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Primack BA, Gold MA, Switzer GE, et al. Development and validation of a smoking media literacy scale for adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006; 160: 369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Primack BA, Hobbs R. Association of various components of media literacy and adolescent smoking. Am J Health Behav 2009; 33: 192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Asssociation for Media Literacy Education. Core Principles of Media Literacy Education in the United States. Cherry Hill, NJ: National Asssociation for Media Literacy Education, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York, NY: Norton, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students–United States, 2011 and 2012. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62: 893–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buller DB, Borland R, Woodall WG, et al. Understanding factors that influence smoking uptake. Tob Control 2003; 12: iv16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montaño D, Kasprzyk D. Chapter 4: theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. (eds). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th edn San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2008, 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- 38.StataCorp. Stata: Release 12. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2012. [Google Scholar]