Abstract

Understanding who establishes partial home smoking bans, what these bans cover, and whether they are an intermediate step in going smoke-free would help to inform smoke-free home interventions. Participants were recruited from United Way of Greater Atlanta’s 2-1-1 contact center. Data were collected at baseline, 3 and 6 months via telephone interview. Participants (n = 375) were mostly African American (84.2%) and female (84.3%). The majority (58.5%) had annual household incomes <$10 000. At baseline, 61.3% reported a partial smoking ban and 38.7% reported no ban. Existence of a partial ban as compared with no ban was associated with being female, having more than a high school education, being married and younger age. Partial bans most often meant smoking was allowed only in designated rooms (52.6%). Other common rules included: no smoking in the presence of children (18.4%) and smoking allowed only in combination with actions such as opening a window or running a fan (9.8%). A higher percentage of households with partial bans at baseline were smoke-free at 6 months (36.5%) compared with households with no bans at baseline (22.1%). Households with partial smoking bans may have a higher level of readiness to go smoke-free than households with no restrictions.

Introduction

For children and non-smokers, particularly those who live with a smoker, the home is often the primary source of second-hand smoke exposure (SHS) [1–5]. SHS exposure causes a range of adverse health effects in both children and adults [3, 6, 7]. Among adults, it causes strokes, lung cancer and coronary heart disease; in children it exacerbates asthma and causes impaired lung function, middle ear disease, respiratory illness and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome [3, 6–9].

Household smoking bans have been shown to decrease exposure to SHS and, recently, third-hand smoke [2, 10–12]. The latter refers to contamination in the form of nicotine and other chemicals deposited on indoor surfaces by tobacco smoke [13, 14]. Household smoking bans also support smoking cessation and reduced cigarette consumption [15, 16], and may help to de-normalize smoking for youth and prevent adolescents from starting to smoke [17, 18].

Although prevalence of home smoking bans has increased markedly over the past two decades, more than half of households with a smoker still allow smoking in the home [5, 19, 20]. In 2010–2011, 46.1% of adults in households with a smoker reported a smoke-free home in contrast to 91.4% of households with no smokers [21]. Smoke-free households are more likely when no smokers live in the home, when young children are present, in higher socioeconomic households, and when a smaller proportion of friends and family members smoke [5, 19, 22, 23].

Because no level of SHS is considered safe, tobacco control efforts and related research tends to focus on smoke-free homes, which are characterized by no smoking allowed anywhere at any time [7, 19]. A significant proportion of households that still allow smoking have some restrictions either in terms of when smoking is allowed or where it is allowed [10, 24–27]. Whether these rules cover other types of smoke and vapor, such as from little cigars, e-cigarettes and marijuana is unknown. Partial bans, defined as allowing smoking at some times or in some places, are often grouped with no bans in analyses [19]. Yet, studies suggest partial bans can result in less exposure and are fairly common among households with a smoker [10, 12, 23].

Households with partial bans may represent settings with higher levels of readiness to go smoke-free than households that have not attempted to reduce exposure to SHS in any concrete way [27, 28]. Alternatively, these households may not be any closer to establishing a smoke-free policy and the difference between a partial ban and no ban may be a matter of interpretation on the part of an individual household member. A qualitative study in the United Kingdom documented that mothers who smoked ‘everywhere’ in their home agreed that smoking in a child’s bedroom would never occur [29]. Others who reported non-smoking homes described situations (e.g. visitors) when smoking occurred inside. Several US studies have noted discrepant reporting of household smoking restrictions by members of the same household, although these discrepancies have decreased in recent years as smoke-free environments have become the norm [5, 30].

To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have carefully described partial smoking bans and examined whether they indicate a household with increased readiness to implement a full ban. This study uses longitudinal data from an intervention trial to understand similarities and differences in households that allow smoking anywhere inside the home (no ban) and those that allow it in some places or at some times (partial bans). In addition to describing partial bans and their correlates, this article also examines whether households with partial bans are more likely to progress to a total ban over time than are households with no smoking restrictions.

Methods

Participants and procedures

These data were obtained from a randomized-controlled trial (RCT) to promote the creation of a smoke free home [31]. Results from the RCT are reported elsewhere [31]. Participants were callers to the United Way of Greater Atlanta 2-1-1 contact center who were recruited to participate in the study. The mission of 2-1-1 contact centers is to connect community members to social services such as assistance with rent or utility bills [32]. Callers were eligible if they allowed any smoking in the home and if they were 18 years of age or older, were a smoker living with a non-smoker or a non-smoker living with a smoker, and if they spoke English. 2-1-1 line agents screened callers for eligibility, consented interested and eligible participants and conducted a baseline survey over the phone using a web-based tracking tool that provided scripts and allowed for online data entry. Line agents screened 4175 callers; 79.7% were ineligible and 8.4% declined to participate or did not complete the eligibility screening or consent process. The full sample of 498 participants was recruited from June 2012 to October 2012. Data were collected at baseline, 3 and 6 months post baseline. Those who completed data collection at all three time points (75.3%) are included in the analysis reported here (n = 375); 24.7% did not have complete data. Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card for completion of each telephone interview.

All participants were verbally consented to participate in the study. It was not feasible to obtain written consent due to the nature of the recruitment process and study procedures. All verbal consent was documented in the online tracking tool and included the date, time and name of agent conducting the informed consent process. Verbal informed consent and research protocol was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01625468).

Although not the focus of this article per se, the 6-week intervention involved three mailings of educational materials supporting creation of a smoke-free home (e.g. Five Step Guide, Challenges and Solutions booklet, photonovella showing a family overcome barriers to going smoke-free), and a coaching call to help participants set goals related to establishing a smoke-free home [31, 33]. Briefly, prevalence of full smoking bans increased in the intervention group from 0% at baseline to 30.4% at 3 months and to 40.0% at 6 months [31]. Prevalence of full smoking bans also increased in the control group, likely due to a measurement effect, from 0% at baseline to 14.9% at 3 months to 25.4% at 6 months. Intent to treat analyses showed a significant intervention effect.

Measures

Because recruitment and baseline data were collected in the context of a busy call center, the baseline survey was short. Home ban status, smoking behaviors and selected demographic characteristics were collected at all three time points. More detailed questions regarding partial bans were included in the 3- and 6-month surveys. Actions to reduce SHS exposure and beliefs about SHS protection were collected at 3- and 6-month follow-up, respectively.

Household smoking bans

At all three time points, participants were asked: ‘Which statement best describes the rules about smoking inside your home?’ [34]. Response options were: smoking is not allowed anywhere inside your home; smoking is allowed in some places or at some times; smoking is allowed anywhere inside the home, or there are no rules about smoking inside the home.

At 6 month follow-up, those with partial bans were asked: ‘Can you describe the rule for me?’ They were also asked about the different kinds of smoke covered by the partial ban, including cigarette smoke, cigar or little cigar smoke, marijuana smoke, electronic cigarette smoke. The survey also included an open-ended question that asked participants to describe their reason for not having a full smoking ban.

Smoking behaviors

Current smokers were asked how long after waking they have their first cigarette, within 5, 6–30, 31–60 or >60 min [35].

Smoke-free home attempts

On the 3- and 6-month surveys, participants were asked, ‘In the last 3 months, has anyone tried to establish a smoke-free rule in your current home?’

Actions to reduce SHS exposure

At 3 months, participants were asked how often someone in their household did the following to reduce exposure to SHS: reminded smoker to go outside, opened the window, only smoked in certain rooms, smoked near a running fan, only smoked indoors when no one is home, only smoked indoors when the children were gone, used quit smoking medication, left the room to smoke, and left the room when smoker was smoking. They were also asked how often someone used air freshener to get rid of the smoke or smell [36, 37]. Responses ranged from 1 = never to 4 = very often

Beliefs about SHS protection

At 6 months, participants rated their beliefs about whether certain actions could protect non-smokers or children from SHS: Based on what you know or believe, how much each of the following actions protects non-smokers and children from SHS. The list of possible beliefs included: Banning smoking everywhere in your home except for one room, using a humidifier, smoking by an open window or door, smoking near a running fan and only smoking indoors when no one is home [36, 37]. Response options were 1 = not at all to 4 = a great deal.

Friends/relatives that smoke

Participants were asked about the number of smokers living in the home and the proportion of relatives and friends who smoked [38].

Sociodemographics

Participants reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity, employment status, educational level, type of housing and number of children in the home.

Statistical analyses

2-1-1 line agents entered baseline data into a web-based data collection system and research staff entered follow-up data into the same system. We ran univariate and bivariate descriptives for all variables and binary logistic regression analysis with ban status at baseline as the outcome variable and demographic and contextual variables as exposure variables. Key analyses were run for control group and intervention group participants separately and for the full sample. SAS 9.3 was used for all data analysis.

Results

Description of study participants

Of the 375 participants who provided data both at 3 and 6 months follow-up, most were female (84.3%), African American (84.2%), not employed (78.7%), and reported a household income of $10 000 or less (58.5%) (Table I). Most households had children in the home (77.3%). The large majority of participants were smokers (80.3%) and most reported not smoking within 60 min of waking up in the morning (76.3%).

Table I.

Baseline demographic and descriptive characteristics of study participants by ban status

| Total n = 375 |

Partial ban n = 230 |

No ban n = 145 |

P-valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 42.7 | 11.18 | 40.4 | 11.16 | 43.9 | 10.90 | 0.003 |

| Gender | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Male | 59 | 15.7 | 29 | 49.2 | 30 | 50.9 | 0.90 |

| Female | 316 | 84.3 | 201 | 63.6 | 115 | 36.4 | <0.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| African American/Black | 315 | 84.2 | 194 | 61.6 | 121 | 38.4 | <0.0001 |

| White | 42 | 11.2 | 27 | 64.3 | 15 | 35.7 | 0.06 |

| Other | 17 | 4.6 | 8 | 47.1 | 9 | 52.9 | 0.81 |

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed | 80 | 21.3 | 50 | 62.5 | 30 | 37.5 | 0.03 |

| Not employed | 295 | 78.7 | 180 | 61.0 | 115 | 39.0 | 0.0002 |

| Income | |||||||

| $10,000 or less | 216 | 58.5 | 129 | 59.7 | 87 | 40.3 | 0.004 |

| $10 001–$20 000 | 100 | 27.1 | 63 | 63.0 | 37 | 37.0 | 0.01 |

| >$20 000 | 53 | 14.4 | 35 | 66.0 | 18 | 34.0 | 0.02 |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than/some high school | 94 | 25.1 | 49 | 52.1 | 45 | 47.9 | 0.68 |

| High school graduate/GED | 144 | 38.4 | 86 | 59.7 | 58 | 40.3 | 0.02 |

| Higher than High School/GED | 137 | 36.5 | 95 | 69.3 | 42 | 30.7 | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 210 | 56.0 | 124 | 62.6 | 86 | 37.4 | 0.01 |

| Married | 66 | 17.6 | 44 | 66.7 | 22 | 33.3 | 0.01 |

| Not married, living w/ partner | 99 | 26.4 | 62 | 62.6 | 37 | 37.4 | 0.01 |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Smoker | 301 | 80.3 | 180 | 59.8 | 121 | 40.2 | 0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 74 | 19.7 | 50 | 67.6 | 24 | 32.4 | 0.003 |

| Time to first smoke after waking up (Smokers only; n = 300) | |||||||

| 30 min or less | 23 | 7.7 | 16 | 69.6 | 7 | 30.4 | 0.06 |

| 31–60 min | 48 | 16.0 | 31 | 64.6 | 17 | 35.4 | 0.04 |

| >60 min | 229 | 76.3 | 132 | 57.6 | 97 | 42.4 | 0.02 |

| Number of smokers in the home | |||||||

| 1 | 187 | 50.0 | 111 | 59.4 | 76 | 40.6 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 137 | 36.6 | 82 | 59.9 | 55 | 40.2 | 0.02 |

| 3 or more | 50 | 13.4 | 37 | 74.0 | 13 | 26.0 | 0.001 |

| Children in the home | |||||||

| Children under 5 in the home | 143 | 38.1 | 84 | 58.7 | 59 | 41.3 | 0.04 |

| Children between 5 and 18 in the home | 147 | 39.2 | 96 | 65.3 | 51 | 34.7 | 0.0002 |

| No children in the home | 85 | 22.7 | 50 | 58.8 | 35 | 41.2 | 0.10 |

| Number of relatives and friends who smoke | |||||||

| Fewer than half | 129 | 34.4 | 80 | 62.0 | 49 | 38.0 | 0.01 |

| Half | 123 | 32.8 | 80 | 65.0 | 43 | 35.0 | 0.001 |

| More than half | 123 | 32.8 | 70 | 56.9 | 53 | 43.1 | 0.13 |

| Reasons for not having full smoking ban | |||||||

| Participant smokes | 163 | 43.5 | 93 | 57.1 | 70 | 42.9 | 0.07 |

| Participant lives with smoker | 52 | 13.9 | 36 | 69.2 | 16 | 30.8 | 0.01 |

| Didn't think of it | 37 | 9.9 | 17 | 46.0 | 20 | 54.1 | 0.62 |

| Smoker doesn't want a total ban | 28 | 7.5 | 19 | 67.9 | 9 | 32.1 | 0.06 |

| Too hard to comply with a rule | 21 | 5.6 | 17 | 81.0 | 4 | 19.1 | 0.005 |

| Unsafe to smoke outside | 10 | 2.7 | 6 | 60.0 | 4 | 40.0 | — |

| It’s not participant's home/not head of household | 8 | 2.1 | 2 | 25.0 | 6 | 75.0 | — |

| Smoking relieves stress | 5 | 1.3 | 5 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| No good place to smoke outside | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | — |

| Can’t leave children alone to smoke outside | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | — |

| Someone else pays bills | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| Not sure/no reason | 57 | 15.2 | 41 | 71.9 | 16 | 28.1 | 0.001 |

Note: Percentages might not add up to 100% due to rounding or refusal to answer.—No tests were performed due to small numbers. aChi-square tests for categorical variables; independent t-tests for continuous variables.

Socio-demographic differences by ban status

Overall, more participants reported partial bans (61.3%, n = 230) than no ban (38.7%, n = 145) at baseline (p < 0.0001). For most demographic categories, this pattern held with partial bans more common than no bans (Table I). Gender was an exception, with men about equally likely to report a partial ban (49.2%) or no ban (50.9%), in contrast to women who were more likely to report a partial ban. Both smokers and non-smokers were more likely to have partial bans than no bans. In additional, more partial smoking bans were reported across the entire sample independent of the number of smokers in the home.

In terms of household composition, those with children under 5 years of age in the home reported higher rates of having a partial ban (58.7%) than having no ban (41.3%). Those with children ages 5–18 had even higher rates of partial bans (65.3%). However, households without children were equally likely to have a partial ban or no ban. Those for whom half or fewer relatives and friends smoked were more likely to report a partial ban than no ban at all.

Reasons for not having a full ban

When asked why they did not having a full smoking ban, most participants (43.5%) reported it was because they smoked themselves (Table I). Other common reasons were living with a smoker (13.9%), did not think of it (9.9%), smoker does not want a ban (7.5%) and no reason (15.2%). Less common reasons were safety concerns about going outside to smoke, the participant was not the head of household, smoking relieves stress, cannot leave children alone and no good place to smoke outside. Differences in reasons by ban status were observed for living with a smoker, too hard to comply and no reason, with all three more commonly reported by those with partial bans.

Description of partial bans

During the 6-month follow-up survey, participants were asked to describe their partial bans. The majority with a partial ban had set up a rule to allow smoking only in designated rooms (52.6%). Commonly mentioned designated rooms included: the bedroom, bathroom and living/common areas. Some of the partial bans were structured around children rather than designated rooms. Approximately 18.4% did not allow smoking in the presence of children. A few (5.6%) described that smoking was not allowed anywhere in the home when children were home or in the children’s room. Others allowed smoking in the home in conjunction with actions such as running a fan or opening a window or door (9.8%). Other rules focused on smoking being permitted in bad weather, for certain guests and at parties or celebrations.

Participants reported that the partial ban covers smoke from cigarettes (96.5%), cigars or little cigars (75.3%) and marijuana (63.5%). More than half (54.7%) included electronic cigarettes in their partial ban.

Multivariate predictors of partial bans

Logistic regression analysis (Table II) investigating predictors of partial smoking bans in contrast to no ban indicate that women were almost twice as likely as men to report a partial ban (OR = 1.93; CI = 1.13, 3.27). Those with educational attainment beyond high school were more likely to have a partial ban (OR = 2.3; CI = 1.36, 3.92) as were those who were married (1.83; CI = 1.01, 3.30), but older participants were less likely to have a partial ban. Participants classified as other race (e.g. not African American or white or mixed race) were less likely to have a partial ban (OR = 0.41; CI = 0.17, 0.99) than African Americans. There were no significant differences due to smoking status, level of addiction, household composition or smoking habits of friends and relatives.

Table II.

Logistic regression model predicting partial home smoking bans

| Variable | OR | (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 1.93 | 1.13 | 3.27 | 0.02 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| African American/Black | 1.00 | |||

| White | 0.86 | 0.46 | 1.62 | 0.64 |

| Other | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.048 |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 1.00 | |||

| Not employed | 0.84 | 0.52 | 1.36 | 0.48 |

| Income | ||||

| $10 000 or less | 1.00 | |||

| $10 001–$20 000 | 1.18 | 0.74 | 1.89 | 0.49 |

| >$20 000 | 1.33 | 0.72 | 2.47 | 0.37 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than/some high school | 1.00 | |||

| High school graduate/GED | 1.53 | 0.94 | 2.51 | 0.09 |

| Higher than high school/GED | 2.30 | 1.36 | 3.92 | 0.002 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.00 | |||

| Married | 1.83 | 1.01 | 3.30 | 0.047 |

| Not married, living w/ partner | 1.10 | 0.69 | 1.75 | 0.70 |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.004 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Smoker | 1.00 | |||

| Non-smoker | 0.82 | 0.33 | 2.08 | 0.68 |

| Time to first smoke after waking up | ||||

| <30 min | 1.00 | |||

| 30–60 min | 0.87 | 0.33 | 2.32 | 0.78 |

| >60 min | 0.61 | 0.26 | 1.44 | 0.26 |

| Number of smokers in the home | ||||

| 1 | 1.00 | |||

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 1.55 | 0.99 |

| 3 or more | 1.22 | 0.67 | 2.22 | 0.52 |

| Children in the home | ||||

| Children under 5 in the home | 1.00 | |||

| Children between 5 and 18 in the home | 1.24 | 0.79 | 1.93 | 0.35 |

| No children in the home | 0.98 | 0.54 | 1.77 | 0.94 |

| Number of relatives and friends who smoke | ||||

| Fewer than half | 1.00 | |||

| Half | 1.16 | 0.71 | 1.89 | 0.56 |

| More than half | 0.81 | 0.50 | 1.32 | 0.40 |

Actions and beliefs about reducing SHS exposure

Using air fresheners to get rid of the smoke or smell, only smoking when no one else is home, and only smoking in certain rooms were the most common actions to address SHS. Such actions were generally more common in households with partial bans, with one exception. Participants with no ban reported higher frequency of smoking indoors only when no one else was home.

When asked about their beliefs on the effectiveness of potential actions to reduce exposure, the only difference was that those with a partial ban had stronger beliefs that banning smoking in the home except for one room would protect non-smokers and children from SHS than did those with no ban. It should be noted that average scores were not high, suggesting beliefs in the protective effects of these actions were not strong (Table III).

Table III.

Actions to reduce SHS exposure at 3 months post-baseline and beliefs about SHS protection at 6 months-post baseline by ban status at time of data collection

| Home smoking ban status at follow-up | Combined |

Partial ban |

No ban |

P-valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actions to reduce SHS exposure at 3 monthsa |

n = 293 |

n = 187 |

n = 106 |

||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Reminded smoker to go outside | 2.60 | 1.11 | 2.86 | 1.05 | 2.13 | 1.07 | <0.0001 |

| Opened the window | 3.02 | 1.08 | 3.22 | 1.00 | 2.66 | 1.14 | <0.0001 |

| Only smoked in certain rooms | 3.11 | 1.05 | 3.40 | 0.83 | 2.58 | 1.18 | <0.0001 |

| Smoked near running fan | 2.41 | 1.16 | 2.40 | 1.18 | 2.42 | 1.13 | 0.86 |

| Only smoked indoors when no one is home | 3.13 | 1.15 | 3.03 | 1.02 | 3.31 | 1.04 | 0.02 |

| Only smoked indoors when the children were gone | 3.02 | 1.08 | 2.98 | 1.06 | 3.09 | 1.11 | 0.41 |

| Used quit smoking medication | 1.46 | 0.81 | 1.49 | 0.84 | 1.42 | 0.72 | 0.46 |

| Left the room to smoke | 2.88 | 1.13 | 3.18 | 0.98 | 2.32 | 1.08 | <0.0001 |

| Left the room when smoker was smoking | 2.47 | 1.21 | 2.75 | 1.17 | 2.34 | 1.12 | 0.004 |

| Used air freshener | 3.36 | 0.91 | 3.45 | 0.88 | 3.19 | 0.94 | 0.02 |

| n = 259 | n = 170 | n = 89 | |||||

| Beliefs about SHS protection at 6 monthsb | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P-value |

| Banning smoking everywhere in your home except for one room | 2.49 | 1.19 | 2.61 | 1.18 | 2.27 | 1.18 | 0.03 |

| Using a humidifier | 2.25 | 1.19 | 2.33 | 1.19 | 2.10 | 1.18 | 0.14 |

| Smoking by an open window or door | 2.56 | 1.03 | 2.64 | 1.02 | 2.43 | 1.05 | 0.12 |

| Smoking near a running fan | 1.78 | 1.00 | 1.73 | 1.01 | 1.87 | 0.99 | 0.30 |

| Only smoking indoors when no one is home | 2.09 | 1.18 | 2.04 | 1.13 | 2.19 | 1.27 | 0.33 |

aResponse options: 1 = never to 4 = very often. bResponse options: 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat or 4 = a great deal. cIndependent t-tests.

Trajectories to full bans

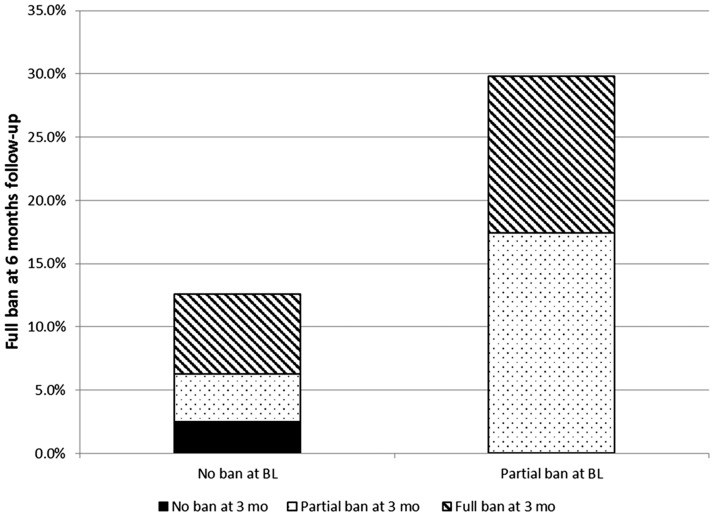

We examined whether households with partial bans at baseline (n = 230) were more likely to have full bans at 3 and 6 months relative to those with no ban at baseline (Table IV). Of the participants who started with a partial ban, 24.0% reported a full ban at 3 months and 36.5% reported a full ban at 6 months. In contrast, of those with no ban at baseline (n = 145), 17.2% reported a full ban at 3 months and 22.1% did so at 6 months. Among control group participants only, of those who started with a partial ban, 17.4% reported a full ban at 3 months and 30.6% reported a full ban at 6 months. Of control participants with no ban at baseline, 7.6% reported a full ban at 3 months and 12.7% did so at 6 months. Overall, at both follow-up time-points, rates for increasingly strict bans were significantly higher for those who had a partial ban at baseline compared with those who had no ban (P < 0.0001).

Table IV.

Home smoking ban status at baseline, 3 and 6 months by baseline ban status

| Baseline home smoking ban status (all participants) |

Baseline home smoking ban status (control group participants) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home smoking ban status | Partial ban |

No ban |

P-value | Partial Ban |

No Ban |

P-value | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Baseline | 230 | 61.3 | 145 | 38.7 | 121 | 60.5 | 79 | 39.5 | ||

| 3 months | ||||||||||

| Full ban | 55 | 24.0 | 25 | 17.2 | 21 | 17.4 | 6 | 7.6 | ||

| Partial ban | 148 | 64.6 | 40 | 27.6 | 81 | 66.9 | 17 | 21.5 | ||

| No ban | 26 | 11.4 | 80 | 55.2 | <0.0001 | 19 | 15.7 | 56 | 70.9 | <0.0001 |

| 6 months | ||||||||||

| Full ban | 84 | 36.5 | 32 | 22.1 | 37 | 30.6 | 10 | 12.7 | ||

| Partial ban | 118 | 51.3 | 52 | 35.9 | 64 | 52.9 | 26 | 32.9 | ||

| No ban | 28 | 12.2 | 61 | 42.1 | <0.0001 | 20 | 16.5 | 43 | 54.4 | <0.001 |

Note: Chi-squared tests

Figure 1 shows trajectories of control group participants who succeeded in making their home smoke-free by 6 months (no participants had a full ban at baseline). Of those with no ban at baseline who reported a full ban at 6 months, half (50.0%) had implemented a full ban already at 3 months, while some implemented a partial ban first (30.2%), and a few still had no restrictions at 3 months. Of those with a partial ban at baseline, 41.6% had a full ban by 6 months, with 58.4% of those already implementing the full ban at 3 months.

Fig. 1.

Trajectories from no or partial ban to full household smoking bans among control group participants.

Discussion

Households with partial bans may be more ready to go smoke-free and/or may signify some level of negotiation among family members to reduce SHS exposure. Our results show that individuals with existing partial bans were more likely than those with no bans to implement full bans over time. These data indicate that those with partial bans may have a greater level of readiness to adopt full bans.

Our data on the trajectories of participants, who succeeded in making their homes smoke free; however do not support the notion that families typically take a stepped approach to implementing full bans. Half of participants who had no ban at baseline and a full ban at 6 months, also had a full ban at 3 months, while a smaller proportion went to partial bans first (at 3 months) prior to implementing full bans at 6 months. These data seem to show that while individuals with partial bans may be more ready to implement full bans than those with no bans, those who are successful at making their home smoke free often go straight from no ban to a full ban.

In the literature, it is uncommon to report progress towards the adoption of full household smoking bans [39]. Often times, households that report partial bans are grouped with those that report no ban in data analyses [5, 40] given the modest effectiveness of partial versus full smoking bans in reducing exposure to SHS and that no level of exposure is considered safe [3, 12, 41]. Unfortunately, this analytical approach makes it difficult to tease out the real-world transitions that households move through on their way to becoming a smoke-free home. Even if lines between no bans and partial bans are blurry when operationalized, those that describe themselves as having a partial ban may be more amenable to a full ban than those saying they allow smoking anywhere at any time. Our study is one of the first to attempt to examine these trajectories.

It is interesting to observe characteristics associated with having or not having a partial smoking ban. In our sample, men and those who had not graduated from high school or a GED program were less likely to have a partial ban. This may be due to lower levels of knowledge about the harmfulness of SHS exposure [42]. Households with children and those with half or fewer friends and relatives who smoked were more likely to have a partial ban. It is likely that those who are exposed to normative smoking behavior infrequently by their peers are more likely to ban smoking in their homes at least at some times or in some parts of the home. Furthermore, parents are likely more concerned than those without children about exposure of the young non-smokers in their home to SHS. These findings are generally consistent with prior research examining correlates of full home bans [5, 19, 22, 23].

In examining multivariate predictors of partial smoking bans, it was most notable that smoking status, time to first cigarette, and friends’ smoking habits did not predict having a partial ban. The characteristics that predicted partial bans versus no bans were all demographic in nature. Participants who were women, married, younger and/or with education beyond high school were more likely to have a partial smoking ban. The findings indicate that people in these demographic categories may be more open to adopting smoke-free home policies. Future interventions should incorporate components that increase their appeal to and effectiveness with single, male and/or low education participants.

The specific nature of partial bans varied across participants. Most who reported partial bans allowed smoking in designated rooms, and about 10% allowed smoking in conjunction with purported SHS reduction behaviors like running a fan, implying that either they incorrectly assumed this would provide adequate protection from SHS or that they acknowledged that this does not provide a safe environment, but may provide other benefits such as reduced smell. Prior research has suggested that the smell of SHS can stimulate rules about smoking in the home [25]. This misinformation and/or harm reduction effort also extends to behaviors aimed specifically at reducing children’s SHS exposure, such as not allowing smoking in children’s presence or in children’s rooms. Further research into households with partial smoking bans should focus on understanding whether they are misinformed (which could be corrected with an informational intervention), or engaging in harm reduction, perhaps because there are barriers to adopting a full ban (in which case interventions could address reducing those barriers). It is of note that more than half of participants stated that e-cigarettes were included in their partial bans, implying that they understand and acknowledge that second-hand vapor may also be harmful.

Not surprisingly, homes with a partial ban status were more likely to report engaging in behaviors to reduce exposure such as reminding smokers to go outside to smoke, opening windows when smoking, and smoking only in certain rooms. Because use of these strategies are conflated with the definition of partial ban it is difficult to tease out whether these are seen as additional attempts to protect household members from SHS or if they represent implementation of the partial ban itself.

The belief that limiting smoking to one room would protect non-smokers and children (a practice carried out by the majority of those with a partial smoking ban) was most strongly held by those with a partial ban while all other beliefs about SHS protection behaviors were similar among those with and without partial bans. These results may indicate a desire on the part of individuals with partial smoking bans to argue that their efforts, while only ‘partial’, can be effective.

Our study had several limitations that should be considered in interpreting results. First our study population was mainly African American and low-income with a lower level of addiction than commonly reported for other groups of smokers. The majority also lived in the Atlanta metropolitan area. Thus, these results may not generalize to other racial/ethnic groups and/or regions and countries. Second, some social desirability bias may have been present given that participants were enrolled in an intervention study to create smoke-free homes. They may also have been more receptive to changing home smoking rules than those choosing not to enroll in the study, thus affecting generalizability. Last, sample size was relatively small for some of the analyses by ban status and study condition.

For public health researchers and practitioners, recognizing partial bans as an intermediate step may facilitate the development of interventions that are tailored to stage of ban adoption. Results from this study show households with partial bans had a greater likelihood of strengthening their ban status. Practitioners may want to target households with partial bans given their possible receptivity to smoke-free home interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank United Way of Greater Atlanta for their help in recruiting study participants and collection of baseline data.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute’s State and Community Tobacco Control Research Initiative, Grant Number U01CA154282.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Homa D, Neff L, King B, et al. Disparities in nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke—United States, 1999–2012. MMWR 2015; 64: 103–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke–United States, 1999–2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59: 1141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wipfli H, Avila-Tang E, Navas-Acien A, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among women and children: evidence from 31 countries. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 672–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Martinez-Donate AP, Kuo D, Jones NR. “How is smoking handled in your home?”: agreement between parental reports on home smoking bans in the United States, 1995–2007. Nicotine Tob Res 2012; 14: 1170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Smoke-Free Policies. In: World Health Organization (ed). Handbooks of Cancer Prevention. Lyon, France: Tobacco Control, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Acute Coronary Events. Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Cardiovascular Effects: Making Sense of the Evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor R, Najafi F, Dobson A. Meta-analysis of studies of passive smoking and lung cancer: effects of study type and continent. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36: 1048–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hood NE, Ferketich AK, Klein EG, et al. Associations between self-reported in-home smoking behaviours and surface nicotine concentrations in multiunit subsidised housing. Tob Control 2014; 23: 27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood NE, Wewers ME, Ferketich AK, et al. Predictors of voluntary home-smoking restrictions and associations with an objective measure of in-home smoking among subsidized housing tenants. Am J Health Promot 2013; 28: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakefield M, Banham D, Martin J, et al. Restrictions on smoking at home and urinary cotinine levels among children with asthma. Am J Prev Med 2000; 19: 188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Destaillats H, et al. Thirdhand tobacco smoke: emerging evidence and arguments for a multidisciplinary research agenda. Environ Health Persp 2011; 119: 1218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winickoff JP, Friebely J, Tanski SE, et al. Beliefs about the health effects of “thirdhand” smoke and home smoking bans. Pediatrics 2009; 123: e74–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills AL, Messer K, Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. The effect of smoke-free homes on adult smoking behavior: a review. Nicotine Tob Res 2009; 11: 1131–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pizacani BA, Martin DP, Stark MJ, et al. A prospective study of household smoking bans and subsequent cessation related behaviour: the role of stage of change. Tob Control 2004; 13: 23–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albers AB, Biener L, Siegel M, et al. Household smoking bans and adolescent antismoking attitudes and smoking initiation: findings from a longitudinal study of a Massachusetts youth cohort. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 1886–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark PI, Schooley MW, Pierce B, et al. Impact of home smoking rules on smoking patterns among adolescents and young adults. Prev Chronic Dis 2006; 3: A41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng KW, Glantz SA, Lightwood JM. Association between smokefree laws and voluntary smokefree-home rules. Am J Prev Med 2011; 41: 566–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills AL, White MM, Pierce JP, Messer K. Home smoking bans among US households with children and smokers opportunities for intervention. Am J Prev Med 2011; 41: 559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King BA, Patel R, Babb SD. Prevalence of smokefree home rules — United States, 1992–1993 and 2010–2011. MMWR 2014; 63: 765–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg CJ, Cox LS, Nazir N, et al. Correlates of home smoking restrictions among rural smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2006; 8: 353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kegler MC, Malcoe LH. Smoking restrictions in the home and car among rural Native American and white families with young children. Prev Med 2002; 35: 334–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Mallya G, Romer D. Beliefs associated with intention to ban smoking in households with smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2013; 16: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kegler MC, Escoffery C, Groff A, et al. A qualitative study of how families decide to adopt household smoking restrictions. Fam Community Health 2007; 30: 328–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulik E, Maroti-Nagy A, Nagymajtenyi L, et al. The role of home smoking bans in limiting exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke in Hungary. Health Educ Res 2013; 28: 130–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei X, Zhang Z, Song X, et al. Household smoking restrictions related to secondhand smoke exposure in Guangdong, China: a Population Representative Survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2013; 16: 390–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friebely J, Rigotti NA, Chang Y, et al. Parent smoker role conflict and planning to quit smoking: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson J, Kirkcaldy A. Disadvantaged mothers, young children and smoking in the home: mothers’ use of space within their homes. Health Place 2007; 13: 894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mumford EA, Levy DT, Romano EO. Home smoking restrictions. Problems in classification. Am J Prev Med 2004; 27: 126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kegler M, Bundy L, Haardoerfer R, et al. A minimal intervention to promote smoke-free homes among 2–1–1 callers: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 530–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreuter MW. Reach, effectiveness, and connections: the case for partnering with 2–1–1 to eliminate health disparities. Am J Prev Med 2012; 43: S420–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kegler M, Escoffery C, Bundy L, et al. Pilot study results from a brief intervention to create smoke-free homes. J Environ Public Health 2012; 2012: 951426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2008brfss.pdf. Accessed: 29 November 2015.

- 35.Fava JL, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. Applying the transtheoretical model to a representative sample of smokers. Addict Behav 1995; 20: 189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sockrider MM. Addressing tobacco smoke exposure: passive and active. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl 2004; 26: 183–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinelli AM. Development and validation of the avoidance of environmental tobacco smoke scale. J Nurs Meas 1998; 6: 75–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norman GJ, Ribisl KM, Howard-Pitney B, Howard KA. Smoking bans in the home and car: do those who really need them have them?. Prev Med 1999; 29: 581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pizacani BA, Martin DP, Stark MJ, et al. Longitudinal study of household smoking ban adoption among households with at least one smoker: associated factors, barriers, and smoker support. Nicotine Tob Res 2008; 10: 533–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binns HJ, O’Neil J, Benuck I, et al. Influences on parents’ decisions for home and automobile smoking bans in households with smokers. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74: 272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackburn C, Spencer N, Bonas S, et al. Effect of strategies to reduce exposure of infants to environmental tobacco smoke in the home: cross sectional survey. BMJ 2003; 327: 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMillen RC, Winickoff JP, Klein JD, Weitzman M. US adult attitudes and practices regarding smoking restrictions and child exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: changes in the social climate from 2000–2001. Pediatr 2003; 112: e55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]