Abstract

Objective

Accelerated atherosclerosis associated with an enhanced inflammatory state, which characterizes ankylosing spondylitis (AS), is the leading cause of increased cardiovascular risk. The objective of this study was to assess carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a surrogate for subclinical atherosclerosis in AS patients and its possible correlation with disease-related clinical parameters.

Methods

We performed a prospective study of 30 consecutive patients meeting modified New York criteria for AS compared to 25 controls matched for age and sex. Patients with traditional CV risk factors were excluded. Disease-specific measures and inflammatory measures (ESR, CRP, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1) were determined. CIMT was measured in the right common carotid artery using high-resolution B-mode ultrasound.

Results

AS patients exhibited increased CIMT compared to matched healthy controls (0.62 ± 0.12 vs. 0.53 ± 0.09 mm). CIMT was positively correlated with age, disease duration, disease activity (BASDAI and ASDAS) and the inflammatory measures ESR (r = 0.45, P = 0.11) and TNF-α (r = 0.62, P < 0.001). CIMT did not correlate with the BMI, BASFI, IL-6, IL-1 or cholesterol levels.

Conclusions

This study shows increased CIMT in AS patients without traditional cardiovascular risk factors compared to healthy controls. An increase in age, disease duration, disease activity (BASDAI and ASDAS), biomarkers of inflammation (ESR and CRP) and TNF-α may predict the occurrence of accelerated atherosclerosis in AS.

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, Atherosclerosis, Carotid intima-media thickness, Inflammatory cytokines

Introduction

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) have an increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Accelerated atherosclerosis caused by a systemic inflammatory response has been reported to be an important risk factor for increased cardiovascular risk for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [3]. The risk of myocardial infarction increases in younger patients and those with more severe disease (defined by disease activity) even after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking and body mass index) in AS patients [4]. Among the various screening methods, carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) according to high-resolution ultrasonography has been established as a clinically useful index for identifying early stage atherosclerosis predicting future cardiovascular events [5].

In the present study, we assessed carotid intima-media thickness in AS patients with matched healthy controls who did not have traditional cardiovascular risk factors. We also studied the possible correlation between CIMT and disease activity and disease ability indices.

Methods

Study Subjects

This was a cross-sectional study in which 55 participants were recruited and divided into two groups. Thirty AS patients (9 females and 21 males, aged 19–49 years) who fulfilled the 1984 modified New York diagnostic criteria for diagnosising ankylosing spondylitis were recruited [6] and 25 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (7 females and 18 males, age 23–48 years) recruited from our clinic staff. Detailed patient and healthy control characteristics are depicted in Table 1. All patients were on a combination of NSAIDs (mostly etoricoxib or piroxicam) and a stable dose of sulfasalazine 1–3 g/day for at least 3 months prior to study enrollment.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the study subjects

| Variable | Ankylosing spondylitis | Healthy controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 30 | 25 | – |

| Age (years) | 34.2 ± 8.7 | 36.9 ± 6.6 | 0.21 |

| Gender: M/F (n) | 21/9 | 18/7 | – |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 3.0 | 22.6 ± 2.7 | 0.57 |

| Smoking (n) | 0 | 0 | – |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 121.5 ± 6.9 | 118.6 ± 6.5 | 0.13 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 83.4 ± 6.0 | 80.9 ± 7.9 | 0.19 |

| Disease duration (years) | 8.7 ± 5.8 | – | – |

| HbA1c (%) | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 4.06 ± 0.7 | 0.23 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 0.81 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.1 | 0.21 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 181.8 ± 17.0 | 179.92 ± 12.5 | 0.29 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 44.6 ± 5.2 | 49.2 ± 4.6 | 0.09 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 103.7 ± 17.9 | 99.4 ± 19.5 | 0.12 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 120.2 ± 17.1 | 125.4 ± 26.2 | 0.16 |

| ESR (mm 1st h) | 29.03 ± 10.29 | 16.64 ± 4.53 | <0.001* |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 14.92 ± 12.71 | 3.78 ± 1.05 | <0.001* |

| BASDAI | 4.89 ± 0.61 | – | – |

| ASDAS | 2.86 ± 0.71 | – | – |

| BASFI | 2.73 ± 1.30 | – | – |

| CIMT (mm) | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.006* |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 9.92 ± 3.74 | 3.26 ± 1.13 | <0.001* |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 18.22 ± 8.44 | 4.0 ± 0.80 | 0.001* |

| IL-1 (pg/ml) | 177.3 ± 88.6 | 90.0 ± 18.9 | <0.001* |

Values are mean ± SD

BMI body mass index, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP C-reactive protein, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, CIMT carotid intima-media thickness, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-a, IL-6 interleukin-6, IL−1 interleukin−1

* P < 0.05

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Clinical Ethics Committee (ICEC), and written informed consent was taken from all the participants. The study subjects with a history of hyperlipidemia [total cholesterol >240 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) >160 mg/dl; prevalence of dyslipidemia defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) criteria] [7], diabetes, smokers and obesity (BMI > 30), coronary artery disease or patients on antihypertensive treatment (blood pressure: systolic >140 mmHg, diastolic >90 mmHg) were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they had a history of alcoholic liver disease, renal insufficiency, stroke, thyroid disorder, multiple sclerosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease or psychiatric disorders. Patients taking medication likely to affect endothelial function (TNF-α inhibitors, steroids, beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, statins and aldosterone antagonist, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor). Patients were also excluded if they had rheumatic disorders other than ankylosing spondylitis.

Clinical and Biochemical Assessment

Patients underwent clinical evaluation at the time of recruitment. Disease activities were calculated and recorded using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [8] and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) including the CRP [9]. The functional status of the patients in our study was evaluated with the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) [10]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the ratio of weight (kg) to height (m) squared (kg/m2). Blood pressure was recorded with a mercury column sphygmomanometer.

Biochemical assessment including a complete blood count, liver function tests, renal function test, vitamin B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, blood sugar and HbA1c were determined using standard commercial kits and urine analysis to detect proteinuria, hematuria and cellular casts. Inflammatory markers, i.e., the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), were measured using the Westergren method and C-reactive protein (CRP) level using standard commercial kits. Inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1 values were also assessed in all subjects by the ELISA method. All patients underwent clinical and biochemical assessment at the time of recruitment. Clinical, biochemical and CIMT assessments were carried out on the same day of recruitment after overnight fasting.

Assessment of Carotid Intima-Media Thickness

All subjects were examined using a high-resolution Doppler ultrasound (HD 11 XE ultrasound machine, Philips Medical System) using a 13–5-MHz linear array transducer in the supine position. The CCA intima-media thickness (IMT) was defined as the average of the maximum IMT of the near and far wall measurements in the distal CCA (1 cm proximal to the carotid bulb). Intima-media thickness was measured at three points on the far walls of both the left and right common carotid arteries (CCA). The three locations were then averaged to produce the mean IMT for each side. All images of the carotid arteries were recorded on the hard disk of the ultrasound system for subsequent analysis and evaluated by a well-experienced radiologist who was blinded to the clinical characteristics of the participants [11]. The subjects had fasted overnight, and they were studied in the morning between 9 and 11 a.m. The intra- and interobserver variability had coefficient of variations is 2.11–2.45%, respectively, for measurements of CIMT.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Patients and healthy control subjects were compared using unpaired Student’s t test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for AS patients to study the relationship between CIMT and clinical and biochemical disease variables. Two-sided P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was carried out using Sigmastat 5.5 for Windows 7.

Results

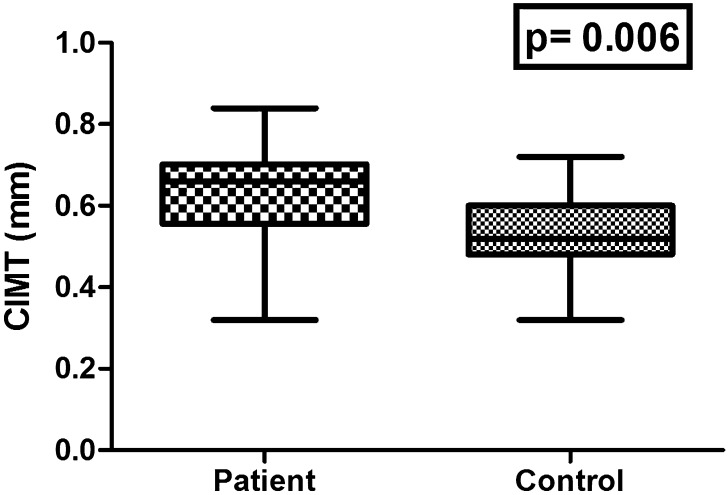

The demographics, clinical and biochemical characteristics of study subjects are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, sex and mean BMI values between AS patients and healthy controls. All study subjects were free from any traditional cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disorders. The clinical index of disease activity (BASDAI and ASDAS) was 4.89 ± 0.61 and 2.86 ± 0.71, respectively, and the functional status (BASFI) 2.73 ± 1.30 at the time of the study (Table 1). There were significant differences in the ESR and CRP levels between the AS patients and controls (both P < 0.001). Total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and HbA1c levels were similar in both groups (P > 0.005). The mean serum level of proinflammatory cytokines, i.e., TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1, in AS patients was higher than that in healthy controls (P < 0.001, 0.001 and <0.001, respectively, Table 1). Compared to healthy controls, AS patients exhibited increased CIMT (0.62 ± 0.12 vs. 0.53 ± 0.09 mm, P = 0.006) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison between mean carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) of both patients and controls

Correlation Analysis of CIMT with Clinical Characteristics and Biomarkers of Inflammation in AS Patients

CIMT was positively correlated with age, disease duration, disease activity measures (BASDAI and ASDAS) and inflammatory markers such as ESR, CRP and TNF-α (Table 2). No significant correlation was observed between CIMT and BMI, BASFI, IL-6 and IL-1 (Table 2). Also no significant correlation was observed between CIMT and total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and TG (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations analysis of CIMT with clinical characteristics and biomarkers of inflammation

| Variables | CIMT | |

|---|---|---|

| r value | P value | |

| Age | 0.39 | 0.04* |

| BMI | 0.33 | 0.07 |

| DD | 0.63 | 0.001* |

| ESR | 0.45 | 0.01* |

| CRP | 0.48 | 0.006* |

| BASDAI | 0.39 | 0.03* |

| ASDAS | 0.46 | 0.009* |

| TNF-α | 0.62 | <0.001* |

| IL-6 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| IL-1 | 0.33 | 0.06 |

| TC | 0.17 | 0.36 |

| HDL | 0.14 | 0.60 |

| LDL | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| TG | 0.12 | 0.52 |

Values were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient

* P < 0.05

Discussion

Results of the present study demonstrate that AS patients without any known traditional cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, obesity and smoking) and CV disorders have a high prevalence of atherosclerosis exhibited by increased carotid intima-media thickness compared to matched controls. Age, disease duration, high disease activity and inflammatory response expressed by the ESR, CRP and TNF-α level emerged as the predictors of subclinical atherosclerotic disease manifested by the increased CIMT using high-resolution B-mode ultrasound. This is the first study to report a significant correlation between TNF-α (inflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of AS) and CIMT in AS. These results may help to explain the increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality observed in AS patients.

AS and another autoimmune rheumatic diseases such as RA and PsA have been known to be associated with accelerated atherogenesis and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [12–14]. Assessment of CIMT is an accepted and established marker to detect early atherosclerosis in asymptomatic subjects; it is considered a strong biomarker of cardiovascular risk [15] and has been extensively used as a surrogate end point in primary intervention studies of cardiovascular risk reduction [16].

The prevalence of increased subclinical atherosclerosis has been studied previously in AS through the assessment of CIMT and FMD, but the partial exclusion of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular events or concomitant medications has led to ambiguous results [17–24]. Hence, we excluded AS patients with traditional cardiovascular risk factors, manifested cardiovascular disease or AS patients on medications (TNF-α inhibitors, steroids, beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, statins, aldosterone antagonist and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) likely to influence atherosclerosis.

In the present study, we demonstrated an increased CIMT in AS patients compared to matched controls. Other studies have also shown a similar increase in CIMT in AS patients in the absence or presence of cardiovascular risk factors. The mean CIMT (0.62 mm) discovered in the present study is comparable to that in reported studies [18, 21, 23]. However, Choe et al. did not find a statistically significant difference between 28 young AS patients with low disease activity and short disease duration (5.0 years) compared to 27 matched healthy controls [25]. This is not surprising given the result of the present study. In a 2008 study by Mathieu et al. that encompassed a series of 60 AS patients with long-standing disease (mean, 11 year) compared to 60 controls, no differences in the CIMT were observed. Almost 50% of the participating AS patients in the Mathieu et al. study had been treated with TNF inhibitors [26].

To date, any relationship among AS variables, inflammatory cytokines and atherosclerosis is merely speculative. On univariate analysis, CIMT was positively correlated with patient age and disease duration, suggesting that patient age and disease duration are associated with increased risk of developing atherosclerosis in AS. Other authors have also reported this association between CIMT and age and disease duration [17, 19, 20, 22–24]. CIMT was positively correlated with increased disease activity, measured using BASDAI scores and ASDAS, in support of the hypothesis that disease activity may influence atherosclerosis in AS patients. A similar, result was confirmed by Hamdi et al. [24], but different findings have been reported by other authors [17, 19, 20, 22, 23].

In addition, we also found that increased CIMT was significantly correlated with inflammatory measures (ESR and CRP), suggesting that systemic inflammation in AS may accelerate the atherosclerotic process. The correlation between CIMT and ESR has been demonstrated by other authors as well [17, 21, 23, 24], while others did not find a significant correlation [19, 20, 22]. An elevated CRP, one of the best surrogate markers of systemic inflammation, is known to promote endothelial cell activation and atherosclerotic processes [27, 28]. CRP has been a particularly consistent predictor of increased risk for atherosclerosis in the general population. Our study is consistent with this observation; higher CRP levels were correlated with increased CIMT in AS. This finding is also supported by Hamdi and coworkers, who reported that CIMT was correlated with the CRP level [24]. The mean CRP (18.9 ± 22.9) reported by Hamid et al. was comparable to the results of our study. This suggests that higher levels of CRP may contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis in AS. In the general population, epidemiologic studies have shown that the CRP level is an independent predictor of CV events [29]. However, no correlation has been observed between CIMT and CRP in AS studies with relatively lower CRP levels [20–26].

We also found that increased CIMT was significantly correlated with TNF-α, suggesting a contribution to progression of increased CIMT in AS. The correlation between CIMT and IL-1 was not significantly correlated in the present study, but it showed a trend toward a positive correlation (P = 0.06). In our study, no correlation was observed between CIMT and IL-6. TNF-α is an important proinflammatory cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of AS and a potential risk factor of cardiovascular risk. High levels of circulating cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1 are in a position to alter the function of distant tissues, including adipose, skeletal muscle, liver and vascular endothelium, to generate a spectrum of proatherogenic changes that includes insulin resistance, a characteristic dyslipidemia, prothrombotic effects, prooxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [30]. Previously, proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1) had not been measured in any of these studies [17, 20–24, 26]. However, Choe et al. estimated the serum level of IL-6 and TNF-α and demonstrated that the serum levels of IL-6 in AS patients was significantly different compared to controls, but not in serum levels of TNF- α. Choe et al. did not find any correlation between CIMT and the serum level of IL-6 and TNF-α in AS. This might be due to the shorter disease duration and low disease activity in the patients included in the study [25]. To the best of our knowledge, the impact of TNF-α blockade on CIMT has not been investigated in AS. However, TNF-α blockade has been shown to improve endothelial dysfunction in AS [31, 32]. A study by Porto et al. in 287 consecutive RA patients demonstrated TNF-α blockade is associated with CIMT reduction, probably by lowering inflammation [33]. Another recent study also demonstrated that TNF- α blockade significantly reduced CIMT as compared to DMARDs in PsA patients [34].

In the present study, we did not find a significant correlation of CMIT with BASFI, BMI and cholesterol levels. BASFI is an index of functionality. Functional disability may occur over a relatively short period of time depending on disease severity. Moreover, BASFI can vary day to day or week to week. Hence, it is not surprising that BASFI did not correlate with CIMT. In keeping with our results, many investigators have not found a correlation between CIMT and BASFI [17, 21–23, 25]. In our study, BMI and total cholesterol, HDL, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides were similar in both groups, as reported in some other studies [22, 23, 25]. Thus, the atherogenic lipid profile cannot completely explain the higher CIMT levels in patients when compared to healthy controls.

Study strength and limitations: This study design had several strengths, notably analyses of a well-characterized patient population and measurement of many inflammatory mediators reported to be associated with accelerated atherosclerosis. A potential limitation of the current study was the small sample size, and the potential confounding effect of synthetic DMARDs (sulfasalazine) on CIMT could not be accounted for in this study. However, this study has identified risk factors for the development of atherosclerosis in AS. These risk factors can serve as potential therapeutic targets to prevent atherosclerosis and hence CV disease in AS patients.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that patients with ankylosing spondylitis without traditional cardiovascular risk factors have increased carotid intima-media thickness compared to matched healthy controls. Age, longer disease duration, increased disease activity (BASDAI and ASDAS), biomarkers of inflammation (ESR and CRP) and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α) are incriminating factors for CIMT surrogate markers of accelerated atherosclerosis in AS. Further studies with larger sample sizes of patients are required to investigate the risk factors and consequences of subclinical atherosclerosis in AS.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the University Grant Commission, New Delhi (Government of India) for providing the research fellowship [no. F.10-15/2007 (SA-I)]. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

I. Verma, P. Krishan and A. Syngle declare no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Clinical Ethics Committee (ICEC), and written informed consent was taken from all the participants.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

References

- 1.Berg IJ, van der Heijde D, Dagfinrud H, et al. Disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis and associations to markers of vascular pathology and traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors: a cross sectional study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:645–653. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters MJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Dijkmans BA, Nurmohamed MT. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with spondyl arthropathies, particularly ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John H, Kitas G. Inflammatory arthritis as a novel risk factor for cardiovascular risk. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:575–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathieu S, Gossec L, Dougados M, Soubrier M. Cardiovascular profile in ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:557–563. doi: 10.1002/acr.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wofford JL, Kahl FR, Howard GR, McKinney WM, Toole JF, Crouse JR., III Relation of extent of extracranialarotid artery atherosclerosis as measured by B-mode ultrasound to the extent of coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:1786–1794. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.11.6.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, Sieper J, Van den Bosch F, Listing J, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1811–1818. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy LG, O”Hea J, Mallorie P, Jenkinson T. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang K, Zou CC, Yang XZ, et al. Carotid intima media thickness and serum endothelial marker levels in obese children with metabolic syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:846–851. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Martin J. Rheumatoid arthritis: a disease associated with accelerated atherogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Llorca J, Amigo-Diaz E, Dierssen T, Martin J, Gonzalez-Gay MA. High prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis in psoriatic arthritis patients without clinically evident cardiovascular disease or classic atherosclerosis risk factors. Arthrtis Rheum. 2007;1557:1074–1080. doi: 10.1002/art.22884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn BH, Grossman J, Chen W, McMahon M. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in autoimmune rheumatic diseases: roles of inflammation and dyslipidemia. J Autoimmun. 2007;28:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bots ML, Grobbee DE. Intima media thickness as a surrogate marker for generalized atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2002;16:341–351. doi: 10.1023/A:1021738111273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bots ML, Evans GW, Riley WA, Grobbee DE. Carotid intima media thickness measurements in intervention studies design options, progression rates, and sample size considerations: a point of view. Stroke. 2003;34:2985–2994. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000102044.27905.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Miranda-Filloy JA, et al. The high prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:358–365. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181c10773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters MJ, van Eijk IC, Smulders YM, et al. Signs of accelerated preclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:161–166. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cece H, Yazgan P, Karakas E, Karakas O, Demirkol A, Toru I, Aksoy N. Carotid intima-media thickness and paraoxonase activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Invest Med. 2011;1(34):E225. doi: 10.25011/cim.v34i4.15364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skare TL, Verceze GC, Oliveira AA, Perreto S. Carotid intima-media thickness in spondyloarthritis patients. Sao Paulo Med J. 2013;131:100–105. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802013000100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrotta FM, Scarno A, Carboni A, Bernardo V, Montepaone M, Lubrano E. Assessment of subclinical atherosclerosis in ankylosing spondylitis: correlations with disease activity indices. Rheumatismo. 2013;23:105–112. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozsahin M, Buyukkaya R, Besir FH, et al. Assessment of carotid intima-media thickness in ankylosing spondylitis patients. Acta Med Mediterr. 2013;29:687–692. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta N, Saigal R, Goyal L, Agarwal A, Bhargava R, Agarwal A. Carotid intima media thickness as a marker of atherosclerosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheumatol. 2014;2014:839135. doi: 10.1155/2014/839135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamdi W, ChelliBouaziz M, Zouch I, et al. Assessment of preclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:322–326. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choe JY, Lee MY, Rheem I, Rhee MY, Park SH, Kim SK. No difference of carotid intima-media thickness between young patients with ankylosing spondylitis and healthy controls. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:548–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathieu S, Joly H, Baron G, et al. Trend towards increased arterial stiffness or intima-media thickness in ankylosing spondylitis patients without clinically evident cardiovascular diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1203–1207. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verma S, Wang CH, Li SH, et al. A self-fulfilling prophecy: C-reactive protein attenuates nitric oxide production and inhibits angiogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000029802.88087.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckley DI, Fu R, Freeman M, Rogers K, Helfand M. C-reactive protein as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:483–495. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattar N, Mc Carey DW, Capell H, McInnes IB. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;108:2957–2963. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Eijk IC, Peters MJ, Serne EH, et al. Microvascular function is impaired in ankylosing spondylitis and improves after tumor necrosis factor α blockade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:362–366. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.086777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syngle A, Vohra K, Sharma A, Kaur L. Endothelial dysfunction in ankylosing spondylitis improves after tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:763–770. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Del Porto F, Lagana B, Lai S, et al. Response to anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha blockade is associated with reduction of carotid intima-media thickness in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1111–1115. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Minno MN, Lervolino S, Peluso R, Scarpa R, Di Minno G, CaRRDs study Group Carotid intima-media thickness in psoriatic arthritis differences between tumor necrosis factor-α blockers and traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:705–712. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.214585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]