Abstract

As the field of behavior analysis expands internationally, the need for comprehensive and systematic glossaries of behavioral terms in the vernacular languages of professionals and clients becomes crucial. We created a Spanish-language glossary of behavior-analytic terms by developing and employing a systematic set of decision-making rules for the inclusion of terms. We then submitted the preliminary translation to a multi-national advisory committee to evaluate the transnational acceptability of the glossary. This method led to a translated corpus of over 1200 behavioral terms. The end products of this work included the following: (a) a Spanish-language glossary of behavior analytic terms that are publicly available over the Internet through the Behavior Analyst Certification Board and (b) a set of translation guidelines summarized here that may be useful for the development of glossaries of behavioral terms into other vernacular languages.

Keywords: Behavior analysis, Glossary, Spanish, Translation

The growth in the number of behavior analysts worldwide, particularly in terms of those working as applied behavior analysts, is perhaps best evidenced by the growing number of Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB®) certificants. As of October 2014, there are 1388 certificants outside the USA who reside in 61 different countries (BACB 2014a). There are 110 BACB-approved course sequences (university training programs that provide the required coursework for BACB certification) outside the USA at 61 different institutions in 28 different countries (J. E. Carr, personal communication, October 27, 2014). The Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) currently has 42 affiliate chapters outside the USA representing thousands of non-US ABAI members (ABAI 2014). The paucity of academic resources (journals, textbooks, and other media) available in languages other than English, from a purely common sense perspective, is likely to impede the rate of growth of behavior analysis in non-English speaking countries. Indeed, although the numbers of BACB certificants outside the USA is growing, this number represents only 7 % of the total number of certificants in the world, by far the greatest proportion resides and works in the USA (BACB 2014a).

The international development of behavior analysis creates the need for tools to both protect the conceptual integrity of the field and facilitate access to high-quality information in the vernacular languages of professionals and clients. In this regard, the development of comprehensive and systematic glossaries of behavioral terms seems crucial. Glossaries are essential reference material for translators, scholars, students, and professionals. They facilitate effective communication, protect the conceptual heritage of the field, and, if developed property, respect the lexical, orthographic, morphological, and phonetic properties of the receiving language. In this article, we will describe the methodological guidelines used to develop a comprehensive and systematic glossary of a vernacular language, using Spanish as a case example. Spanish is an important target language: it is spoken by over 350 million speakers worldwide, is the official language of 20 countries, and is the most common second language in the USA with 35 million speakers (Instituto Cervantes 2007). Finally, Spanish-speaking countries, such as Spain, Mexico, and Colombia, have a thriving behavioral community.

Process Factors

The initiative to create a glossary developed along with the need to provide reference materials for Spanish-speaking students. The advisory board was comprised of a convenience sample of behavior analysts fluent in both English and Spanish. Most board members had a background of collaboration with the first author (TJCG, MC, CD, EFiB, MSFP, AG, CH-P, SL, RMR, JNG, CNG, LVA, AZS). The first author purposely invited some board members because of their particular positions and reputation in the field (WL, OGL, RHP). For example, Wilson Lopez is the president of ABA Colombia and Rocio Hernández Pozo was at the time the editor of the Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis, the only journal specializing in behavior analysis published in a Spanish-speaking country. We invited scholars and practitioners that had Spanish as the first language and English as the second language and vice versa. We recruited a higher number of primarily Spanish scholars (12 in 16) because Spanish was the language targeted for translation. We also included scholars with applied (10) and basic research (6) backgrounds. Finally, we invited scholars from different Spanish-speaking countries in order to ensure that the glossary would have a degree of transnational acceptability.

As per the development process, the first author conducted a preliminary translation of the initial corpus of behavioral terms. Subsequently, the glossary went to the board for review. Each board member reviewed every term independently and sent comments and suggestions about specific terms. Most of the suggestions were straightforward and were accepted directly. On a few occasions, specific terms required further discussion between the authors or between the first author and a board member. On a few occasions, the first author discussed specific translations with the linguistic service of the Real Academia Española (2014). The resulting preliminary version of the glossary was used during four major translation assignments in order to expand the glossary and check its usability. During the course of these assignments, the first author coordinated the addition of approximately 300 terms that were not present in the original version. After these assignments were completed, the glossary was sent to the advisory board for a new review. All advisory board members reviewed all terms in the glossary. Some of the advisory committee members participated in the second review only (MV, AG, SL, JNG). Approximately, 300 terms required discussion between the board members and one or more of the authors during the two feedback cycles. The final version of the glossary went through a final check by one of the authors with a background in Spanish philology (JAMG). This last step resulted in corrections and modifications in approximately 20 terms.

Assuming that each board member might have used an average of 10 to 30s to review each word during each review cycle, the committee may have invested 100 to 300 h during the process of reviewing the glossary. This estimation does not include the time necessary for (a) creating the initial corpus of words, (b) conducting the initial translation, (c) engaging in discussions after each feedback cycle, and (d) conducting the translation assignments. Computing these additional aspects of the process would result in several thousands of man-hours. The complete process developed intermittently over a period of 5 years (2009–2014).

Development of a Corpus of Behavioral Terms

In order to create a comprehensive corpus, we amalgamated 11 published glossaries and repositories of behavioral terms (Catania 2006; Cooper et al. 2007; Greer and Ross 2007; Johnston and Pennypacker 2009; Mazur 2005; Miltenberger 2012; Newman et al. 2003; Pierce and Cheney 2008; Pierce and Epling 1999; Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 2010). Terms that were not field-specific were not included in the glossary (e.g., depression, thematic research) unless used frequently in the behavior-analytic literature (e.g., self-injury, destructive behavior).

General Translation Guidelines

Our translation guidelines were intended to produce precise translations, protect the lexical, orthographic, morphological, and phonetic integrity of the receiving language, and allow for local variations in the receiving language. Specifically, we sought to minimize terminological redundancy, maximize the use of equivalent lexemic and non-lexemic terms, use periphrases when equivalent terms were not available, minimize the use of Anglicisms, and achieve transnational consensus across Spanish-speaking countries for the translated terms.

Minimize terminological redundancy. Where possible, synonymic English terms (e.g., schedule-induced behavior, adjunctive behavior) were translated to a single Spanish term (e.g., conducta inducida por programa). Among the English variations available, we selected for translation the term that allowed for a direct translation without resorting to loanwords or Anglicisms. For example, we favored the term schedule-induced behavior that, unlike adjunctive behavior, allows for a direct Spanish translation (conducta inducida por programa). In a few cases, the English term allowed for more than one equally correct translation; on such occasions, we provided all correct translations. For example, the term applied behavior analysis can be translated either as análisis aplicado de conducta or análisis de la conducta aplicada because applied qualifies both behavior and analysis. On occasions when redundant terms seem to reflect subtle semantic differences, distinct preferences across authors, or a terminological drift that may have occurred over an extended period of time, we chose to preserve both terms (e.g., post-reinforcement pause and preratio pausing; multi-element design and alternating treatments design).

Maximize lexemic and non-lexemic equivalents. We endeavored to identify Spanish lexemic equivalents of the English terms (e.g., reforzador for reinforcer). A lexemic equivalent is a word already in existence in the receiving language, which is part of the same cognate group that the original English term belongs to. Namely, both the original term in English and the translated term in Spanish share the same stem or lexeme (e.g., Latin prefix re followed by the Latin verb fortiāre). This approach is possible only among languages that either derive from or have been influenced by a common language, in this case Latin. If a lexemic equivalent was not available, we looked for Spanish non-lexemic equivalent terms. A non-lexemic equivalent is a word that exists in the receiving language with the appropriate denotation, but is etymologically unrelated to the original English term. For example, behavior can be accurately translated with conducta,1 yet the terms have unrelated etymologies. In a more unusual example, the term precurrent behavior may be accurately translated as conducta antecesora. Interestingly, although precurrent derives from the Latin occurrĕre, it does not have a lexemic equivalent in Spanish, making the potential Anglicism precurrente less desirable.

-

Use practical periphrases when necessary. When equivalent terms were not available, we entertained multi-word definitions or periphrases. Periphrases, if relatively brief, are still desirable translations. For example, the term self-management lacks equivalents in Spanish (that is if we ignore the integrated Anglicism auto-manejo). Yet, the term could be translated faithfully from the original English with the periphrasis gestión de la autonomía personal (literally, management of personal autonomy). In yet another example, the term ratio run lacks accurate direct translations and may be faithfully translated with the periphrasis incremento de respuesta asociado a programas de razón (literally, increment in responding associated with a ratio schedule). On the few occasions when a non-lexemic equivalent was available but was less accurate or self-explanatory than a short periphrasis we provided both. For example, for parroting (Greer and Ross 2007), we provided both the non-lexemic equivalent cotorrear and the more self-explanatory periphrasis repetición preecoica, literally pre-echoic repetition.

Nonetheless, we should note that a periphrasis might not as easily accommodate the changes in gender, number, and tense as an equivalent single term could. Thus, whenever possible, lexemic and non-lexemic equivalents are preferable to periphrases.

Minimize Anglicisms. The translation of technical terms into a vernacular language is a common gateway for incoming Anglicisms. Several factors suggest that direct use of foreign terms in a vernacular language is an inadvisable practice. First, the phonetics of the English word are unlikely to be preserved in the target language leading to misspelling and mispronunciation. Second, foreign words interjected into a target language are unlikely to adapt to the gender, number, and tense variations of the target word. Third, terms directly translated may be subject to semantic interference if the target words exist in the receiving language with a different meaning. For example, the term bizarre vocalization if translated directly as vocalizaciones bizarras may lose its original meaning for bizarro in Spanish means brave or audacious. Finally, importing terms directly from English gives the wrong impression that science is the product of a single language or culture. Anglicisms may take many forms (see, for example, Haugen 1950). We defaulted to the use of Anglicisms in the very rare cases when lexemic, non-lexemic equivalents, and periphrases were not possible. We first considered integrated Anglicisms, which preserve the lexeme from the original term but adapt its orthography to the receiving language (e.g., autoclítico for autoclitic). We limited this approach to English terms with a Latin stem for which other members of the same cognate group could be identified in Spanish or terms with a Latin stem that were introduced into English as neologisms. An example of the former scenario, tact in English and tacto in Spanish are both derived from the Latin tactus. An example of the latter scenario, codic, introduced as a neologism (Michael 1982) and with a Latin stem (codex or codĭcus), was translated as the integrated Anglicism códico. The least preferable option involved using a non-integrated Anglicism: a word taken directly from the English as is. We limited this approach to Anglicisms already in use by the Spanish behavioral community (e.g., naming). On those occasions we accompanied the non-integrated Anglicism with a more equivalent translation as an alternative (e.g., denominación is a lexemic equivalent of naming).

Achieve transnational consensus. There are 22 academies of the Spanish language all bound to a pan-Hispanic dictionary, orthography, and grammar (Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española 2005, 2010, 2011; Real Academia Española 2000, 2001). We used these as reference material during the process of developing our glossary. In addition, we followed the methodological guidelines of the International Test Commission (2010) on the adaptation of psychological instruments into different languages. Specifically, the guidelines D.1 through D.5 suggest the following: (a) use various strategies to ensure that the translation process takes full account of the linguistic and cultural differences among the populations for whom adapted versions of the translation are intended; (b) provide evidence that the language use is appropriate for all cultural and language populations for whom the translation is intended; and (c) provide systematic evidence, both linguistic and psychological, to improve the accuracy of the adaptation. Transnational consensus was established by way of an advisory committee. Once the initial translation was completed, we appointed an advisory committee to evaluate transnational acceptability. Committee members were bilingual academics or practitioners (12 primarily Spanish, 4 primarily English; Spanish-speaking countries represented: Spain, Mexico, Colombia, Panama, Cuba, Argentina, and the USA) with a background in either applied or experimental behavior analysis. The committee’s feedback resulted in either the selection of two Spanish translations or agreeing to a single translation by consensus. For example, the term reliability is often translated as confiabilidad in Mexico and as fiabilidad in Spain. Both translations are accurate non-lexemic equivalents. Thus, both were included. In another example, the term data path can be translated as sendero de datos in Mexico and as línea de datos in Spain. We selected a third term that would be acceptable in both countries (trayectoria de datos). Finally, the whole process was overseen by a specialist in Spanish philology (JAMG). In addition, the consultation service of the Real Academia Española (2014) was used on a discretionary basis.

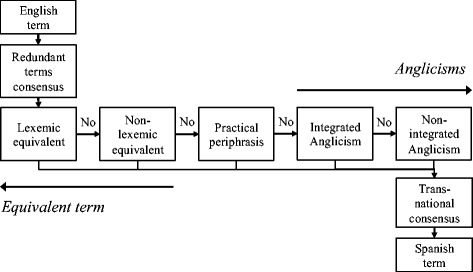

Implementation of Translation Guidelines and Outcome

Figure 1 summarizes the process of implementing our translation guidelines. First, we identified any redundant English words for the target term and selected a single term wherever possible. Subsequently, we endeavored to find a Spanish lexemic equivalent of the English term. If lexemic equivalents were not available, we sought Spanish non-lexemic equivalent terms. Third, when lexemic and non-lexemic equivalents were not identified, we developed a practical periphrasis. When practical periphrases were not attainable, we adapted the English word as an integrated Anglicism. The use of non-integrated Anglicisms was limited to English terms already in use in the Spanish behavioral community. Table 1 presents examples of the five translation approaches used.

Fig. 1.

Translation process

Table 1.

Examples of the five translation methods used

| English | Spanish |

|---|---|

| Lexemic equivalents | |

| Adduction contingency | Contingencia de aducción |

| Antecedent stimulus class | Clase de estímulos antecedentes |

| Behavioral momentum | Momento conductual |

| Mand | Mando |

| Parametric design | Diseño paramétrico |

| Non-lexemic equivalents | |

| Arbitrary matching | Igualación arbitraria |

| Believability | Credibilidad |

| Bizarre vocalizations | Vocalizaciones inapropiadas |

| Overt behavior | Conducta manifiesta |

| Yoked schedules | Programas enyugados |

| Practical periphrases | |

| Overexpectation effect | Efecto de la expectativa elevada |

| Peak shift | Cambio del pico de discriminación |

| Preratio pausing | Pausa previa a la razón de reforzamiento |

| Ratio run | Incremento de respuesta asociado a programas de razón |

| Scalloping | Respuesta con patrón festoneado |

| Integrated anglicisms | |

| Autoclitic | Autoclítico |

| Intraverbal | Intraverbal |

| Negative automaintenance | Automantenimiento negativo |

| Overmatching | Sobreigualación |

| Self-stimulatory behavior | Conducta autoestimulada |

| Non-integrated anglicismsa | |

| Behavioral priming | Imprimación o priming conductual |

| Naming | Denominación o naming |

| Role-play | Ensayo conductual o role-play |

aThere are only three non-integrated Anglicisms in the glossary. They are accompanied with lexemic or non-lexemic equivalents as alternative translations

After the translation of the term by any of these five approaches, we submitted the preliminary translation to a multi-national advisory committee. Subsequently, the glossary was proof-tested and expanded over a period of 5 years while conducting four major translation assignments: translation of BACB exams into Spanish (2011), translation of the Simple Steps® system into Spanish (Keenan et al. 2014), translation of the handbook Behavior Modification (5th ed.) into Spanish (Miltenberger 2013), and translation of new BACB exam forms (2014). Lastly, the pre-final version of the glossary was submitted again to the multi-national advisory committee to check translational acceptability and identify any departures from the translation guidelines.

Through the method described above we have translated a corpus of 1228 English behavioral terms. The glossary is publicly available over the Internet through the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2014b) and ABA España (2014) both in pdf and Apple Dictionary formats. The translation guidelines delineated here may help to preserve conceptual and linguistic integrity. They may also be useful for the development of glossaries of behavioral terms in other vernacular languages.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the members of the advisory board Dr. Tomás Jesús Carrasco Giménez (Spain), Dr. Maricel Cigales (USA), Dr. Carrie Dempsey (USA), Dr. Esteve Frexa i Baque (France), Dr. Maria Xesús Froján Parga (Spain), Dr. Oscar García Leal (Mexico and Spain), Dr. Aníbal Gutiérrez (USA), Dr. Rocío Hernández Pozo (Mexico), Dr. Camilo Hurtado-Parrado (Colombia), Dr. Sarah Lechago (USA and Argentina), Dr. Wilson López (Colombia), Dr. Rafael Moreno Rodríguez (Spain), Dr. Jose Navarro Guzmán (Spain), Dr. Celia Nogales González (Spain), Dr. Luis Valero Aguayo (Spain), and Dr. Alejandra Zaragoza Scherman (Mexico). Also, Dr. Brian Iwata answered terminological questions posed by the first author. This article does not constitute an official position of the BACB. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Javier Virués-Ortega, School of Psychology, The University of Auckland, Tamaki Campus, Private Bag 92019, 261 Morrin Rd, Auckland 1072, New Zealand (E-mail: j.virues-ortega@auckland.ac.nz).

Footnotes

The terms conducta and comportamiento are used interchangeably in Spanish. However, we have favored the term conducta: (a) conducta is defined by the Spanish language academies as “actions of an organism in response to a situation,” while comportamiento has a much wider semantic scope; (b) the adjective for conducta is used widely (i.e. conductual), while the adjective for comportamiento (comportamental) is a low-frequency term; (c) comportamiento is a verbal noun derived from the reflexive verb comportarse, while conducta is derived directly from a Latin noun (conducta); and (d) the reflexive verb comportarse suggests that the action of the organism is caused by an unspecified internal mechanism.

References

- Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española . Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. [Pan-Hispanic dictionary] Madrid: Espasa; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española . Ortografía de la Lengua Española [Orthography of the Spanish language] 2. Madrid: Espasa; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española . Gramática Básica de la Lengua Española [Basic grammar of the Spanish language] Madrid: Espasa; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Behavior Analysis International (2014). Chapter information. Retrieved from: http://www.abainternational.org/constituents/chapters/international-chapters.aspx.

- Behavior Analysis Certification Board (2014a). Certificant Registry. Retrieved from http://bacb.com/index.php?page=100155.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board, Inc. (2014b). International Resources. Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/index.php?page=100199.

- Catania AC. Learning. 4. Cornwall-on-Hundson: Sloan Pubhishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ABA España (2014). Glosario de terminos conductuales. [Glossary of behavioral terms]. Retrieved from http://www.aba-elearning.com/documentos/glosario.pdf.

- Greer RD, Ross DE. Verbal behavior analysis. Boston: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen E. The analysis of linguistic borrowing. Language. 1950;26:210–231. doi: 10.2307/410058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insituto Cervantes (2007). Enciclopedia del español en el mundo. Anuario del Instituto Cervantes 2006-2007 [Encyclopedia of Spanish in the world. Annual report of the Instituto Cervantes 2006-2006]. Madrid, Spain: Author.

- International Test Commission (2010). International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests. Retrieved from http://www.intestcom.org/Guidelines/test+adaptation.php.

- Johnston JM, Pennypacker HS. Strategies and tactics for human behavioral research. 3. Hillside: Erlbaum; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, M. et al. (2014). Simple Steps [Spanish version]. Retrieved from http://www.simplestepsautism.com/?lang=es.

- Mazur JE. Learning and behavior. 6. Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Skinner’s elementary verbal relations: some new categories. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1982;1:1–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03392791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger RG. Behavior modification. 5. New Jersey: Cengage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger RG. Modificación de conducta [Behavior modification] 5. Madrid: Pirámide; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Newman B, Reeve KF, Reeve SA. Behaviorspeak. A glossary of terms in applied behavior analysis. New York: Dove and Orca; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce WD, Cheney CD. Behavior analysis and learning. 4. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce WD, Epling WF. Behavior analysis and learning. 2. Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española (2014). Formulario de consultas lingüísticas [Linguistic consultation service form]. Retrieved from http://www.rae.es/consultas-linguisticas/formulario.

- Real Academia Española . Diccionario de dudas y dificultades de la lengua española de Manuel Seco [Dictionary of special cases of the Spanish language] 10. Madrid: Espasa; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española . Diccionario de la lengua española [Dictionary of the Spanish language] 22. Madrid: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (2000–2010). Author-generated keywords of the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior and the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, period 2000–2010.