Abstract

Throughout history, individuals have changed the world in significant ways, forging new paths; demonstrating remarkable capacity to inspire others to follow; and repeatedly showing independence, resilience, consistency, and commitment to principle. However, significant cultural change is rarely accomplished single-handedly; instead, it results from the complex and dynamic interaction of groups of individuals. To illustrate how leaders participate in cultural phenomena, I describe how a few individuals helped to establish the Cold War. In this analysis, I distinguish two types of cultural phenomena: metacontingencies, involving lineages of interlocking behavioral contingencies, and cultural cusps, involving complicated, unique, and nonreplicable interrelations between individuals and circumstances. I conclude that by analyzing leaders’ actions and their results, we can appreciate that cultural and behavioral phenomena are different, and although cultural phenomena are inherently complex and in many cases do not lend themselves to replication, not only should the science of behavior account for them, cultural phenomena should also constitute a major area of behavior analysis study and application.

Keywords: Behavior analysis, Cultural analysis, Cultural contingencies, Cultural cusps, Culturant, Metacontingencies

In studying leadership, rather than beginning with our current understanding of behavior and extrapolating to leaders’ actions and accomplishments, I assumed that the field of behavior analysis has much to learn. Instead of presuming we have answers, I began by inquiring how known leaders behaved and participated in significant cultural phenomena. Therefore, I titled this paper, “What Studying Leadership Can Teach Us About the Science of Behavior.” I studied the lives of known leaders to determine if they displayed similar repertoires and learned how their legacies came to be. I tried to answer three questions: (1) do effective leaders possess common repertoires?, (2) what is the role of the leader within complex cultural phenomena?, and (3) does the science of behavior analysis account for leadership within cultural phenomena?

Do Effective Leaders Show Common Repertoires?

In thinking about leadership, I first explored how leaders behave. To avoid the immediate challenge of how to identify true leaders, I opted to study biographies of individuals from the present and past who have been credited with significant accomplishments and who were widely known, so readers might easily relate to them through personal knowledge and experience. I introduced my own bias in the selection, as the individuals I chose interest me. In examining these biographies, I found that four characteristics consistently stood out across all: (1) commitment to principle, (2) independence, (3) resilience, and (4) consistency.

Principle Driven: Governed by a Set of Beliefs

On June 12, 1964, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (1918–2013) was sentenced to life imprisonment for sabotage against the South African apartheid regime. During his trial, on April 20, 1964, Mandela stood up in his own defense and concluded:

I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die. (Mandela 1995, chap. 56)

Those were Mandela’s final words before going to prison for 27 years. On the day of his release, February 11, 1990, at age 71, he gave his first speech as a free man to crowds in Cape Town’s City Hall. He said, “I wish to quote my own words during my trial in 1964. They are as true today as they were then” (Mandela 1995, chap. 100).

During his imprisonment, Mandela was offered freedom in exchange for renouncing his cause but his commitment to pursue equal opportunities for all South Africans was nonnegotiable. Like Mandela, many others dedicated their lives to their missions: Martin Luther King’s (1929–1968) well-known speech of August 28, 1963, describes his life’s cause: “I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.” He fought for equality of blacks in the USA until his assassination in 1968. In The Souls of Black Folk, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868–1963) said, “To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships” (Du Bois 1994, para. 5). He spent his life forcefully working for full civil rights and increased political representation for African Americans (Du Bois 1897). Édouard Manet (1832–1883) did not compromise on the artistic value of a new style of painting in late 1800s France. In the face of tremendous rejection, he helped to transition painting from realism to impressionism (King 2006).

Others dedicated their lives to causes that had tremendous adverse impact. For instance, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) led the French Revolution and seized control of most of continental Europe in pursuit of a unified Europe under French control (Fisher 2010). Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) believed the world would be better by preserving the purity of a “master race”—the Aryans. Joseph Stalin (1878–1953) was convinced that the proletariat must build the socialist society. Pol Pot (1925–1998) attempted to create a purely agrarian-based communist society. As leader of the Khmer Rouge (1963–1999) and prime minister of Democratic Kampuchea (today’s Kingdom of Cambodia), Pol Pot justified genocide; under his regime, approximately 20,000 mass graves known as the “killing fields” were created and filled between 1975 and 1979.

These individuals were all leaders who lived by their beliefs, regardless of whether their causes were noble. They persuaded, influenced, and directed others to follow—they were driven by principles, whether positive or negative.

Independence: Defy Status Quo

In 1997, Apple launched the “Think Different” campaign:

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. . . .They create. They inspire. They push the human race forward. . . .the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do (Isaacson 2013, p. 439).

Steve Jobs (1955–2011) put his heart and soul in each word and image of this advertisement. He was a living example of challenging the status quo with his contributions. As Isaacson (2013) put it, Jobs “passion for perfection and ferocious drive revolutionized six industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing, and digital publishing” (p. 3). He transformed the computer industry by marrying elegance of design and functionality at Apple like no one had done. He demonstrated his genius and ability to depart from current thinking at the end of Apple product launches with his famous “and one more thing,” which preceded the unveiling of the most innovative features. He directed the creation of unprecedented animated movies like Toy Story, at Pixar. He persuaded the music industry of something thought inconceivable—to allow customers to buy songs singly rather than being forced to buy a whole album, one of the features of the iPod and iTunes that forever changed the music industry. He made magic over and over again until his death in 2010, innovating portable phones with the iPhone, tablet computing with the iPad, and digital publishing with the iBook (Isaacson 2013).

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) defied all conventions. Although later considered the personification of genius, as a child, he was a slow learner. As an adult, he was unable to find a job or get recommendations until age 22, when, with the help of a family friend, he was hired as a clerk in a Swiss patent office, processing paperwork for inventions. While there, he wrote four papers—based purely on thought experiments—in his spare time regarding the composition of light, the existence of atoms and molecules, the true size of atoms, and a modification of the theory of space and time—all of transcendent scientific value. His last paper defied Isaac Newton’s (1643–1727) unchallenged concept of “absolute space and time,” which later “would become known as the Special Theory of Relativity. Out of it would arise the best-known equation in all of physics: E = mc2” (Isaacson 2008, p. 2).

A letter from Einstein to Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) warned FDR that the Germans might have the atomic bomb. This letter provided the impetus to contract the physicist Julius Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967) as the scientific director of Los Alamos National Laboratory of the Manhattan Project. Between 1942 and 1946, Oppenheimer directed Nobel Prize-winning scientists in the development of atomic bombs and their deployment in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, putting an end to World War II. Afterward, Oppenheimer spent the rest of his life pursuing nuclear disarmament (Bird and Sherwin 2006). Einstein, FDR, and Oppenheimer in different ways moved away from conventional understanding of their fields and made significant developments in physics, politics, and military strategy.

Marie Skłodowska-Curie (1867–1934) became the most famous female scientist of the twentieth century. She challenged the status quo throughout her life. Raised in Russian-dominated Poland, she studied Polish history, language, and literature in clandestine schools throughout Warsaw. After much struggle, she entered the Sorbonne 8 years after her graduation from high school, at a time when women did not have the right to vote. She excelled in a male-dominated field and graduated first in her class for her masters in science and second in her class for her second masters, in mathematics. Later she worked with Pierre Curie, laboratory chief at the Paris School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry, who she married in 1895. She pursued an unconventional career and research, earning two Nobel Prizes in two disciplines: in physics, codiscovering the theory of radioactivity, and in chemistry, discovering polonium and radium (Steward 2013).

A more contemporary example of the ability to defy the status quo is Elon Musk (1971–present). He is making reality of what is commonly thought to be science fiction: electric cars, humanoid robots, hyperloops in airspace to travel between cities, and spaceship voyages to other planets. He is revolutionizing space exploration, with the stated goal of preserving the human race: He hopes to be able to send humans to Mars in 10 to 20 years with Space Exploration Technologies (2002), known as SpaceX. He is helping to accelerate the production of electric cars, the manufacture of compact and innovative automotive batteries, and expanding the network of supercharger stations with Tesla Motors (2003). And he is contributing to the development of solar power systems with SolarCity (2006).

Many other leaders in history across different domains were nonconformist, like Pablo Ruiz y Picasso (1881–1973) who defied the standards of the twentieth century painting with Cubism and a wide variety of styles, and Burrhus Frederic Skinner (1904–1990) who in essence created the science of behavior analysis. Successful leaders surpass conventional standards and stand up for what they believe (Isaacson 2011, 2014).

Resilience: Able to Bear Hardship

Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu, Mother Teresa (1910–1997), was a small, sickly nun, who dedicated her life to help the “poorest of the poor” and lived among them in one of the most impoverish cities in the world—Calcutta, India. There she created the Missionaries of Charity, a Catholic congregation where nuns provide assistance to the needy, the dying, and the sick, those with HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, leprosy, and other deadly diseases. Her congregation established orphanages and schools and encompassed 4000 sisters, 610 missions, 123 countries, and over one million volunteers. She earned the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 and was beatified in 2003 as “Blessed Teresa of Calcutta” (Seba 1997; Spink 2001).

It is hard to conceive that Mother Theresa would inspire much criticism. However, she has been called a demagogue for accepting donations from leaders who abused human rights and accused of not providing quality medical care in spite of receiving substantial donations. She has been critiqued for not using pain relievers and for employing high-risk practices, such as reusing needles and failing to impose medical protection to caregivers (Afi and Morgan 1994; Hitchens 1995). The most consistent criticism of her regarded her campaign against abortion: At her Nobel Peace prize acceptance speech, she said, “the greatest destroyer of peace today is abortion, because it is a direct war, a direct killing, direct murder by the mother herself” (Mother Teresa 1979). But no criticism ever stopped her.

As First Lady, Hillary Rodham Clinton (1947–present) failed to gain approval from Congress on health-care reform (1994)—a major government initiative. She survived the Whitewater investigation (1996) by an independent counsel, Travelgate, the scandal of Bill Clinton’s (1946–present) extramarital affairs, and his impeachment hearings during his second term (1998). She is the only First Lady subpoenaed to testify before a federal grand jury. Most of us would have quit, but not Clinton. She went on to become the only US First Lady to run for public office and became the first female senator from New York (2001); she was reelected (2006), became a Democratic presidential primary candidate (2008), and is 67th secretary of state under President Barack Obama (1961–present). Currently, she is the leading Democratic candidate for the 2016 presidential elections. She has been called many names, but one well deserved is “resilient” (Bernstein 2007; Clinton 2003, 2014).

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945–present), also known as the “Lady of No Fear” (Ulsteen and Bonne 2010), was detained in Burma in 1990, right before the elections in which the party she lead, the National League for Democracy, won with 59 % of the vote. She remained under house arrest for 15 of the next 21 years for her firm political stand on freedom and human rights, first articulated in her speech in August 26, 1988. In 1971, while living in Oxford, she married Michael Aris, a scholar of Tibetan culture. When her mother had a stroke, she went back to Burma and never left, not even in 1997 to be with her dying husband. (She would most likely not have been granted reentry to the country.) She is certainly an example of resilience, as pointed out in the article “Test of Wills: The Burmese Captive Who Will Not Budge” (Mydans 2005). It seems that her fight will never be over: Most recently, a parliamentary committee voted against changing a clause in Myanmar’s Constitution that bars her from becoming president or vice president because she was married to and had children with a foreigner (Bengtsson 2012; Wintle 2007).

I briefly met Benazir Bhutto (1953–2007) in San Francisco at a women’s leadership conference in the early 1990s, while she was living in exile and advocating for human rights and democracy in Pakistan. Dressed with a traditional shalwar kameez, she related her story. She was the first woman elected head of an Islamic state’s government, the 11th prime minister of Pakistan, and had served two nonconsecutive terms in 1988–1990 and in 1993–1996. She survived an attempted coup d’état in 1995, was removed from power, imprisoned, separated from her young children and family, and put in solitary confinement for years (Bhutto 2008). She returned to Pakistan after President Pervez Musharraf (1943–present) granted her amnesty and withdrew corruption charges. There on December 27, 2007, 2 weeks before the 2008 election in which she was the leading candidate, she was killed in a bombing. In short, great leaders do not quit when things get tough. Mother Teresa, Hilary Clinton, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benazir Bhutto, and all leaders mentioned so far lived through major struggles and did not give up.

Consistency: Practice What You Preach

In June 26, 2006, Warren Buffett (1930–present), chairman, CEO, and the largest shareholder of the world-renowned Berkshire Hathaway investment company, donated $37 billion to the Gates Foundation—the largest philanthropic donation ever made. In addition, he gave $6 billion to the foundations of his three children and late wife. Buffett, by 2008 the wealthiest man in the world, believes in value investing and frugality. He said that he used the same strategy for outsourcing philanthropy and for making money, “finding good organizations with talented managers and backing them” (“The new powers in giving” 2006). By supporting his friend Bill Gates (1955–present), he used his wealth to have a significant impact worldwide. Buffett, well known for his frugality, lives in the house he bought in 1958 for $33,000, drives a regular car, and has reasonably modest offices. Here is a man who, at an early age, personified frugality, even washing his car when it rained to save water (Schroeder 2009). He practices what he preaches.

Born and raised in the Russian nobility, Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) had a tumultuous early life: he was a heavy gambler, an excessive partygoer, and a failure at his university education. After unsuccessful attempts at farming and soldiering and after experiencing an existential crisis, he adopted fervent Christian beliefs, although he remained opposed to organized religion. Ousted by the Russian Orthodox Church, and consistent with his newfound principles in the last 30 years of his life, he followed a spiritual path, took positions of pacifism and nonviolent resistance, and renounced material possessions and desires of the will. His burial site is consistent with his beliefs—a mound in the shape of a coffin with no marker in the woods of Yasnaya Polyana is, as he requested, simply a reminder of the place where he played as a child, as opposed to a monument to one of the greatest writers of all times. He lived and died practicing what he advocated.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), who dressed with a traditional Indian dhoti and a handwoven shawl, was the embodiment of simplicity and defiance with nonviolence. However, he also said, “where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence” (Borman 1986, p. 253). In August 1947, he led India’s independence from Britain, but in January 1948, he was assassinated during the battles that ended with the separation of Pakistan. His preaching was consistent with his actions. Nonviolent civil disobedience and humility dominated his life’s arduous work for an independent and united India (Gandhi 1983).

Buffett, Tolstoy, and Gandhi lived in manners consistent with their beliefs. Mother Teresa lived among the poor and shared the conditions of their lives. Nelson Mandela treated all with the same respect that he hoped for himself and so inspired respect from authorities and his fellow prisoners. “Actions speak louder than words.”

The leaders I studied inspired and influenced others through their commitment to their principles, independence, resilience, and consistency. They have been credited with extraordinary contributions, as diverse as the independence of South Africa from Britain, the establishment of Apple, and the development of the Catholic congregation Missionaries of Charity. However, as I explored their lives, I learned that rarely, if ever, does any individual single handedly change the course of history or have a substantial cultural impact. Even in the case of the extraordinary women and men I explored, I found that there are always others who also participated to shape the course of events and the accomplishments.

As Gladwell illustrated in his book Outliers (2008): not “Robert Oppenheimer, not rock stars, not professional athletes, not software billionaires and not even geniuses—ever makes it alone” (p. 115). He argued that culture, circumstances, and the timing of events have a heavier impact on legacies than individual leaders. The leaders I studied found themselves in unique circumstances, interacted with others who contributed in significant ways, and without whom, their presumed accomplishments would not have come into being. We tend to aggrandize individuals, giving them more credit than perhaps is warranted.

How Do Leaders Affect Cultural Phenomena?

In this section, I attempt to illustrate that leaders are, as a group, not single handily responsible for significant achievements through complicated, unique, and nonreplicable interrelations, influenced by exceptional circumstances. As a matter of illustration, and at the risk of appearing either oversimplifying or overelaborating, I use a concrete example familiar to most—the beginnings of the Cold War that let to 45 years of direct and indirect political and military confrontations around the world between the Western Block led by the USA and the Eastern Block led by the Soviet Union.

The Cold War began with the perceived threat of the Soviet Union expansion as a world power after World War II and the conviction that the USA had the responsibility to contain its expansion and protect freedom and democracy around the globe. Between 1945 and 1952, three strategic initiatives helped to codify these goals in US foreign policy, giving birth to the Cold War: (1) the Truman Doctrine (1947), through which the USA provided unprecedented military and economic assistance to Greece and Turkey to prevent control by the Soviet Union; (2) the Marshall Plan (1949–1952), also known as the European Recovery Plan (ERP), through which Europeans and the USA collectively helped rebuild Europe after World War II and support democratic regimes; and (3) the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a coalition committed to military cooperation against attacks on any member nation (1949–present) when economic and political power did not suffice.

Leaders

In their book, The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made, Isaacson and Thomas (1986) argued that six leaders were the concealed architects of the three initiatives that launched the Cold War: two lawyers, Dean Gooderham Acheson (1893–1971) and John Jay McCloy (1895–1989); two bankers, William Averell Harriman (1891–1986) and Robert Abercrombie Lovett (1895–1986), and two diplomats, George Frost Kennan (1904–2005) and Charles Eustis Bohlen (1904–1974). These men all became government advisers after they retired from public life. In approximately 850 pages, the authors masterfully described the unfolding of events and how the actions of these six men shaped the establishment of the Cold War (Isaacson 1986). I examined the authors’ work, and that of others, in an effort to understand the development of the three initiatives from a behavioral cultural perspective, thinking that many cultural phenomena present similar characteristics.

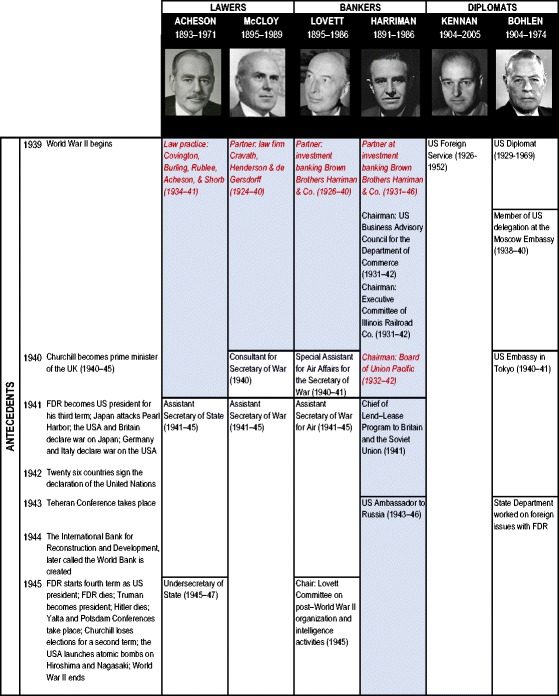

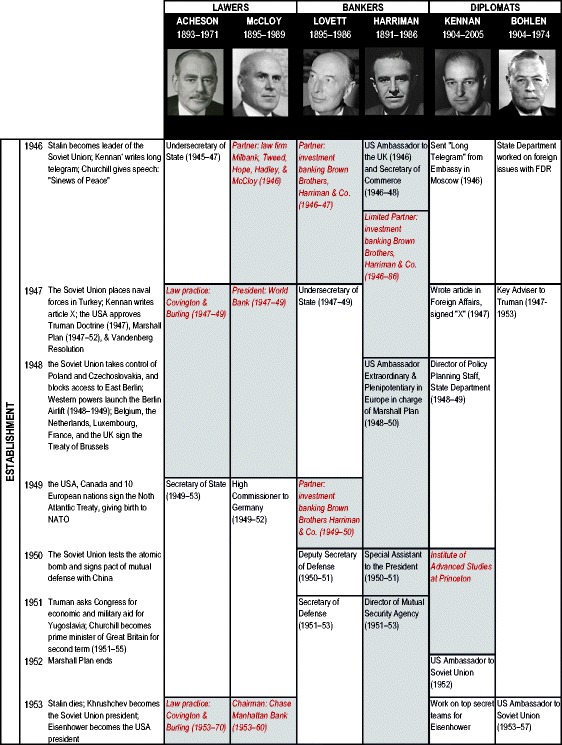

Table 1 shows the role these men played both in and outside of the US government during critical events preceding the Cold War between 1939 and 1945. Table 2 shows their roles during the establishment of the Cold War between 1946 and 1953, including the creation of the Truman Doctrine (1947), the conception and implementation of the Marshal Plan (1947–1952), the formation of NATO (1949), and the transition of power in the Soviet Union with Stalin’s death and the beginning of Dwight D. Eisenhower's (1890-1969) term as president of the USA in 1953.

Table 1.

Role of the six wise men during antecedent events to the Cold War (1939–1945)

Shaded cells and colored italics in Table 1 and Table 2 indicates positions outside of the US government, mainly in private businesses. The sources of the six wise men photographs of Table 1, Table 2, and Figure 2 are as follows: Dean G. Acheson. Photograph cropped from https://www.flickr.com/photos/9364837@N06/2378493712/. In the public domain. Example reference: Dean G. Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State. Retrieved October 5, 2015 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/9364837@N06/2378493712/; John J. McCloy. Photograph cropped from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=30023. In the public domain. Example reference: Formal portrait of John J. McCloy in front of a world map. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=30023; Robert A. Lovett. Photograph cropped from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=21315. In the public domain. Example reference: Portrait of Secretary of Defense Robert A. Lovett at his desk at the Pentagon. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=2131; W. Averell Harriman. Photograph cropped from http://moscow.usembassy.gov/w_averell_harriman.html. In the public domain. Example reference: U. S. Ambassadors to Russia: W. Averell Harriman (1943-1946). Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://moscow.usembassy.gov/w_averell_harriman.html; George F. Kennan. Photograph cropped from http://moscow.usembassy.gov/george_kennan.html. In the public domain. Example reference: U. S. Ambassadors to Russia: George F. Kennan (1952). Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://moscow.usembassy.gov/george_kennan.html; George F. Kennan. Photograph cropped from http://moscow.usembassy.gov/charles_bohlen.html. In the public domain. Example reference: U. S. Ambassadors to Russia: Charles E. Bohlen (1953-1957). Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://moscow.usembassy.gov/charles_bohlen.html.

Table 2.

Role of the six wise men during the establishment of the Cold War (1939–1953)

Two Lawyers

Acheson and McCloy had worked in some of the most prestigious law firms involved in international trade. Acheson was a partner at Covington, Burling, Rublee, Acheson, & Shorb from 1934 to 1941. Later, he worked at Covington & Burling between government appointments (1947–1949) and returned to his private practice there after leaving office (1953–1970). McCloy worked at Cravath, Henderson, & de Gersdorff in 1924 to 1940 and in Milbank, Tweed, Hope, Hadley, & McCloy in 1946. He became president of the World Bank (1947–1949) initially established as the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development in 1944 and chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank (1953–1960).

In government, Acheson had a career at the State Department, where he served as an assistant secretary of state (1941–1945) and undersecretary of state (1945–1947). In 1949, he became secretary of state and served in this capacity until the end of Truman’s presidency, in 1953 (Beisner 2006). McCloy started as a consultant in the War Department in 1940. Later, he served as an assistant secretary of war (1941–1945) and US high commissioner for Germany (1949–1952).

Two Bankers

Lovett and Harriman were experts on investments and trade between the USA and Europe. Lovett joined the then largest private investment banking firm in the USA, Brown Brothers Harriman & Company in 1926 to 1940 (Isaacson and Thomas 1986, p. 112) where he eventually became partner in 1946. There, he managed the bank’s lending operations in Europe and imports of metals, raw materials, and foodstuffs. Harriman established Brown Brothers Harriman & Company in 1922 through a merger and was a partner from 1931 to 1946 and limited partner from 1946 to 1986. He had inherited the Union Pacific Railroad built by his father, Edward Henry Harriman (1848–1909), and served as chairman of the board from 1932 to 1942. Harriman also owned several other important private businesses.

In government, Lovett became an assistant secretary of war for air affairs for the secretary of war (1940–1941) and assistant secretary of war for air (1941–1945). He chaired the Lovett Committee on post-World War II organization and intelligence activities (1945), served as an undersecretary of state (1947–1949), deputy secretary of defense (1950–1951), and secretary of defense (1951–1953). While Harriman maintained his private businesses, he served as chairman of the Committee of Illinois Railroad Company (1931–1942), chairman of the US Business Advisory Council for the Department of Commerce (1937–1939), chief of lend-lease program to Britain and the Soviet Union (1941), US ambassador to the Soviet Union (1943–1946), US ambassador to the UK. (1946), and secretary of commerce (1946–1948). He was in charge of the Marshall Plan in Europe (1948–50). He became special assistant from the president (1950–1951) and director of the Mutual Security Agency (1951–1953).

Two Diplomats

Kennan and Bohlen were Soviet experts and spent most of their lives in the US Foreign Service. In addition to Harriman, Kennan and Bohlen became ambassadors to the Soviet Union: Kennan in 1952 and Bohlen from 1953 to 1957. From 1926 to 1952, Kennan served as US Foreign Service officer in Geneva, Hamburg, Berlin, Estonia, Latvia, Moscow, Vienna, Prague, Lisbon, and London. Bohlen served as US diplomat in the State Department from 1929 to 1969, including an assignment to the US Embassy in Tokyo (1940–1941) and Moscow (1943–1944). He became counselor of foreign issues to FDR and key advisor of Soviet affairs to Truman (1938–1940 and 1947–1953). He also served as US ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1957.

These six men also had personal ties. For instance, Harriman and Acheson attended Groton Boarding School and Yale, where Harriman recruited Acheson to row in the freshman crew. Harriman and Lovett were childhood friends. Lovett’s father worked for Harriman’s father, who had built the Union Pacific Railroad where Lovett’s father eventually became chairman. Both Harriman and Lovett went to Yale, worked at the railroad, and were business partners. Kennan and Bohlen were close intellectual colleagues and friends. These men worked and socialized together (Herken 2014). They influenced one another and persuaded others on what they believed to be the best course of action for US foreign policy (Isaacson and Thomas 1986).

Cold War Antecedents

A series of critical events starting at the beginning of World War II in 1939 set the occasion for the establishment of the Cold War, without which the six wise men’s actions would not have had lasting impact. In 1940, Winston Churchill (1874–1965) became prime minister of the UK. Events began to unfold quickly on December 7, 1941, when the USA entered World War II as a result of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The USA had maintained a politics of isolationism, but when forced into the war, it became immediately engaged in diplomatic and trading efforts with Britain and the Soviet Union and other allies against Nazi’s Germany. In 1942, the Declaration of the United Nations was signed by 26 countries that bound them in war efforts.

In 1943, Churchill and Joseph Stalin (1878–1953) met in person for the first time at the Teheran Conference to strategize steps against Germany. In 1945, a major turn of events took place. In February, Churchill, FDR, and Stalin met for the second time at the Yalta Conference to plan Europe’s post-war reorganization. In April, FDR died and Harry S. Truman (1884–1972) became president (“A Sudden Collapse” 1945). In the same month, Hitler dies. In May, Germany declared unconditional surrender. In July, Truman joined Churchill and Stalin at the Potsdam Conference to discuss the division and reconstruction of Europe. During the Conference, it became known that Churchill had lost the elections for a second term as prime minister of the UK. In August, the USA dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II (Dobbs 2012).

Cold War Establishment

Soon after the War, Stalin engaged in aggressive efforts for expansionism in Eastern Europe, becoming increasingly clear that he would not honor the commitments agreed in the previous conferences with the leaders of the UK and the USA. Kennan articulated the Soviet intent to expand its sphere of influence and weaken the West in his famous “Long Telegram” (of more than 5000 words), which he sent on February 22, 1946, from the Soviet Embassy to the State Department. Kennan said, “USSR still lives in antagonistic ‘capitalist encirclement’ with which in the long run there can be no permanent peaceful coexistence” (Kennan 1946, p. 3). Until that point, Kennan’s warnings had been mostly ignored at the State Department, but Harriman, who fully agreed with Kennan’s assessment widely distributed the telegram, and with others’ influence, their position became broadly accepted. On March 5, 1946, Churchill described the problem facing the world in his speech, “Sinews of Peace.” Churchill said:

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. . . . subject. . . . to a very high and, in some cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow. (Churchill 1946)

The speech describes the circumstances that gave rise to the Cold War. Moving forward, the USA would make every effort to contain the expansion of the Soviet Union totalitarian regime in pursue of freedom and democracy throughout the world. Within the next 3 years, the three initiatives that institutionalized the Cold War were approved by the US Congress: the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and the formation of NATO.

The Truman Doctrine

Truman had only served 3 months as vice president when FDR died and had met with him only twice, on topics of no consequence. He had no experience in foreign policy and had travelled outside of the USA only two times. He was unaware of the Manhattan Project and the development of the atomic bomb, as well as the early agreements between FDR, Churchill, and Stalin. Nevertheless, Truman learnt fast. He listened, trusted, and delegated responsibility to those with knowledge and skill. He was decisive and led the country during one of the most difficult periods of contemporary history (McCullough 1992, 2003; Truman 1947; Truman Library Institute 2010).

Within days of his appointment as president, he became aware of the tensions with the Soviet Union through Bohlen and Harriman, who had hurried back from his ambassador appointment in Moscow to alert Truman, Acheson, and others. Lovett became instrumental in creating the strategy for post-World War II organization. Acheson would become very influential in Truman’s administration. Under Secretary of State George Catlett Marshall (1880–1959) from 1947 to 1949, Acheson practically served as an acting secretary (Beisner 2006). He ran the department’s day-to-day happenings, communicating issues in writing and consulting Marshall only for major decisions (Isaacson and Thomas 1986). He supported Truman with tremendous loyalty, following his direction even if he disagreed, and defended him and his strategies in public and behind the scenes (Beisner 2006; Chace 1998). Truman thought that Acheson was one of the best secretaries of states the USA had ever had, and they became friends after they left office.

In 1947, Kennan published a private report titled “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” in Foreign Affairs. The author was identified as “X,” and the piece became known as the “X-Article,” an account for the policy of containment addressed to the general public (“X” [Kennan] 1947). Kennan became known as “the father of containment” but spent most of his life arguing that his points had been misinterpreted, as he meant to consider political, not military strategy (Gaddis 2006, 2011; Sullivan 2015; Thompson 2009). Nevertheless, Bohlen, Acheson, and Harriman persuaded Truman about “basic and irreconcilable differences of objective between the Soviet Union and the United States” (Isaacson and Thomas 1986, p. 19) and of the need to help rebuild Europe after the war. They interpreted the placement of Soviet naval forces in Turkey as Moscow’s strategy of military advancement toward the control of Europe and the eastern Mediterranean and expansion to the Middle East.

With input from Bohlen, Lovett, Harriman, Kennan, McCloy, and others, Acheson conceived the strategy that would lead Congress to approve a request for economic aid to Turkey and Greece, serving as an example of how the USA would move to prevent Soviet expansion and aid “free peoples” around the world. Acheson oversaw the preparation of Truman’s speech to a joint session of Congress (Beisner 2006) of March 12, 1947, when Truman declared, “it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures” (Truman 1947, p. 34), and requested $400 million in assistance for Greece and Turkey. This policy became known as the Truman Doctrine and was approved by Congress in just 2 months, on May 22, 1947.

The Marshall Plan

First in social and private gatherings, the notion evolved that, rather than combating communism directly with military force, the USA would provide vast financial aid to support an economic recovery plan laid out by allied European countries ravaged at the end of the war. The assistance to Europe’s economic recovery was planned to contain the expansion of Stalin’s control on the continent and develop loyalty to the USA. Truman suggested that the plan be named for Marshall, who was esteemed by both parties and was one of the most respected generals of World War II, US Army chief of staff, and FDR’s chief military adviser. Again, with Acheson’s ability to get congressional support and the input of others, Marshall introduced the European Recovery Plan (ERP), later known as the Marshall Plan at the commencement address at Harvard University in June 1947. He said that the USA “should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace” (Marshall 1947). “He warned Congress that if the USA was unable or unwilling to effectively assist in the reconstruction of Western Europe, the continent would fall to the Soviet Union dictatorship” (Isaacson and Thomas 1986, p. 432). Harriman provided Congress a 3-in.-thick report depicting the details of the plan. The plan was drafted in June 1947 and signed 10 months later on April 3, 1948.

In 1947, McCloy became president of the then only 8-month-old International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, later called the World Bank. Convinced that Europe needed private investments to help with its recovery, McCloy sought out businessmen and investors, many of whom were his friends, making the case for the creation of a market for US trade in Europe that would address the dollar surplus in the USA and combat communism for the sake of freedom and democracy. He was successful, and private investments made possible the first loan to France for $250 million (Isaacson and Thomas 1986, pp. 428–429).

Truman appointed Harriman to administer the Marshall Plan in Europe. Harriman was given enormous power and made things happen without much red tape (Isaacson and Thomas 1986, p. 442). From 1947 to 1952, the USA provided $13 billion to aid countries with reconstruction and needed resources, including thousands of tons of coal, tractors, fishing nets, and bread.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The Marshall Plan was not enough to obstruct Stalin’s expansionism efforts. Between 1947 and 1948, the Soviet Union took control of Poland and Czechoslovakia and blocked access to East Berlin. In spite of the “Berlin Blockade,” the USA kept its commitment to economic expansion described in the Marshall Plan, but at the same time prepared for military intervention. As tensions intensified, the possibility of war between the USA and the Soviet Union became a widespread concern.

In March 1948, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and the UK signed the Treaty of Brussels to ally against Soviet domination in Europe. Lovett worked with his close friend and colleague Senator Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg (1884–1951), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1947, to produce what was called the Vandenberg Resolution. This resolution specified circumstances under which armed forces would be used in the interest of international peace and security through the United Nations (Vandenberg Resolution 1947). A year later, the North Atlantic Treaty was signed joining the Brussels’ alliance with the USA, along with Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland (North Atlantic Treaty 1949). Acheson was the signer of the treaty on behalf of the USA, which gave birth to NATO. The goal was “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down” (Reynolds 1994, p. 13), as stated by NATO’s first secretary general, Hastings Lionel “Pug” Ismay (1887–1965). NATO has grown today to be an organized military organization of 28 nations with headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. In 1950, the Soviet Union tested the atomic bomb and signed a pact of mutual defense with China. In 1951, Truman asked the Congress for economic and military aid for Yugoslavia, and Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain for a second term (1951–1955). In 1952, the Marshall Plan ended. In 1953, Stalin died, Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) became president of the Soviet Union, and Eisenhower became president of the USA (Miller 2012).

Isaacson and Thomas (1986) concluded that these six wise men were behind the scenes designers of the containment of Soviet expansion. As Acheson put it, “The growth of Soviet power requires the growth of counter-power among those nations which are not willing to concede Soviet hegemony” (Acheson 1958, p. 17). None of these men could have single handedly accomplished the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, or NATO, but collectively and with others’ help, they made these developments happen. Kennan articulated the position of containment. Bohlen, Kennan, and Harriman, through their work in Moscow, became convinced that the Soviets would do anything to expand their sphere of influence with oppressive regimes. They persuaded Acheson, McCloy, Lovett, and others who in turn swayed the president and the US State, War, and Treasury departments. They ignored public opinion and perhaps exaggerated the facts in order to win over others. Kennan and Bohlen brought inside knowledge of Soviet conduct; Harriman and Lovett brought trade, banking, and investment expertise; Acheson and McCloy brought knowledge of international legal transactions. Lovett and McCloy contributed with the assessment of military power. Acheson contributed with his ability to pass policy through Congress and operationalize the containment strategy (Acheson 1969).

Does Behavioral Science Account for Leadership Within Cultural Phenomena?

It could easily be assumed that those who specialize in the science of behavioral change could address the role of leaders in significant cultural phenomenon, such as the influence of these six wise men’s actions in the establishment of the Cold War. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case. We are limited by our emphasis on behavioral contingencies and failure to acknowledge that cultural contingencies are of a different nature. Behavioral and cultural phenomena involve different units of analysis. In this section, I delineate the difference.

Behavioral Contingencies vs. Metacontingencies

Behavioral Contingencies

Behavioral contingencies focus on behavior of single individuals over time. Skinner argued that to understand the culture “we must turn to the contingencies that generate them” (Skinner 1971, p. 127). Behavior analysts have followed Skinner’s advice and focused on the behavioral contingencies that affect individuals. We identify critical behaviors, perform functional analyses, manipulate environmental variables, and measure behavior change. Based on the notion that consequences determine the “future probability” of responses that will produce them, behavioral interventions consist of evaluating the effects of environmental manipulations on repetitions of behavioral contingencies over time (Malott 2008; Malott and Glenn 2006; Skinner 1953, 1974). The locus of change in behavior analysis is lineages of behavioral contingencies of single organisms (Glenn 1991, 2003, 2004). Most behavior analytic research includes this type of intervention, which indeed produces successful results across many types of behaviors, populations, and settings (Cooper et al. 2007; Martin and Pear 1999; Miltenberger 2001).

The issues involved in the establishment of the Cold War are complex: dynamic systems are part of the environment where individuals behave, aggregate products affect individuals and systems in different ways, and unpredictable events impact the whole scheme of interrelations. Reducing this complexity to the study of individual operant behavior is simply unattainable and impractical.

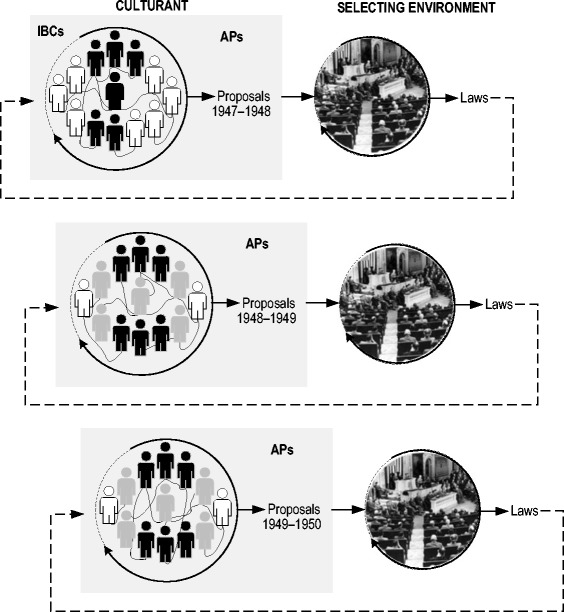

Metacontingencies

Glenn introduced the concept of metacontingency (Glenn 1988, 1991, 2003; Glenn and Malagodi 1991). The term is defined as “a contingent relation between (1) recurring interlocking behavioral contingencies having an aggregate product and (2) a selecting environment.1” This concept is helpful to understand a specific type of cultural phenomena involving lineages of relations. As a matter of illustration, Fig. 1 represents an entity that was instrumental in the establishment of the Cold War—the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The figure includes the elements of metacontingencies: (1) aggregate products (APs), (2) interlocking behavioral contingencies (IBCs), (3) culturant, (4) selecting environment, and (5) lineages of culturants and their selecting environments.

Fig. 1.

Metacontingency depicting selection of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee (1947–1950) culturant by the US Congress-approved laws. The photograph of the US Congress included in Fig. 1 was cropped from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=4476. In the public domain. Example reference: President Harry S. Truman addressing a Joint Session of Congress on the threat to the freedom of Europe, March 17, 1948. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=4476

Aggregate Products

Most complex cultural phenomena involve products generated by the actions of multiple individuals. For example, the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee (FRC) generates proposals of treaties, bills, and resolutions pertaining to the foreign policy of the USA. Those recommendations are the FRC’s aggregate products. During World War II, this committee was particularly influential in persuading the US Congress to transition from an isolationist to an internationalist foreign policy, which encouraged political and military cooperation of the USA with other countries.

Interlocking Behavioral Contingencies

The 1947–1948 committee was formed by 13 senators, and their IBCs resulted in bipartisan foreign policy proposals. No single senator could have generated recommendations to the US Congress on behalf of the committee; the interaction of all of the committee’s members was required. They needed to act as a group. The behavioral contingencies involved in the actions of the committee’s members were interlocking in that elements of contingencies or their products of one senator’s actions served as elements of the contingencies or products for the another senator’s actions. For instance, a report generated by one senator might have served as a prompt for another senator’s request of support from an influential individual in the US Congress.

Culturant

The actions of each individual in the committee are maintained by operant behavior. But as mentioned earlier, given the complexity of the interactions, it would not be practical to focus on the study of each operant contingency because many behaviors are not relevant to the generation of the aggregate product. The focus is on the IBCs that generated specific proposals. The AP/IBCs relations constitute a culturant (Hunter 2012).

Selecting Environment

The recommendations of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee eventually go to the US Congress for approval, and with the US President’s endorsement, the recommended bills, treaties, or resolutions become law. In Fig. 1, the selecting environment refers to the actions of the US Congress regarding the committee’s recommendations and its results. The US Congress either rejects, modifies, or endorses proposals and eventually proposes laws to the US President. The US Congress serves as a selector, and its approval of laws recommended by the FRC constitutes the selecting environment of the committee’s culturants—that is, the relations between the IBCs and their resulting proposals. If the committee’s recommendations are never approved, its dynamics would change and eventually the committee would cease to exist.

Lineages of Culturants and Their Selecting Environments

Nowadays, the Senate FRC Committee reviews about 50 treaties a year. The process the committee follows to make recommendations recurs 50 times in a year. In Fig. 1, the recurrence of IBCs is illustrated with a circle and arrow. The US Congress, which in this example serves as the selector, could also be studied as a more complex metacontingency than the FRC culturant selection. For instance, in 1947, the US Congress, formed by 96 senators, 435 representatives, and 3 non-voting members, passed 395 bills into law. The dynamics of IBCs and Congress resolutions also involve lineages of interrelations. In contrast, the Senate FRC had only 13 members in 1947 and made fewer recommendations; one of them was the Truman Doctrine, introduced on March 12, 1947, and passed 2 months later; another proposal was the Marshall Plan, introduced on June 5, 1947, and passed into law 10 months later.

As with operant lineages, in metacontingencies there is variation in the recurrences of the culturants, (both in the IBCs and their correspondent APs) and their selecting environments. Although the process is similar, variations do take place, such as in the length of the approval process and the participants. Figure 1 shows variations in the senators that formed the FRC of the 80th (1947–1948), 81st (1948–1949), and 82nd (1949–1950) US Congresses. Figures in black represent the senators that remained in the committee for 3 years, from 1947 to 1950; figures in gray represent senators who remained for 2 years, from 1948 to 1950; and figures in white represent senators who remained for 1 year. The lines between senators vary by year to illustrate that with members’ turnover, there is also change in the committee’s dynamics. However, despite the rotation of some senators, core members remained on the committee for three consecutive congresses, allowing for lineages of relations between the committee’s culturants and their selection by Congress resolutions. If all of the senators on the committee were replaced each year, there would not be lineages of relations. In such a case, the FRC would not be described as part of a metacontingency.

Behavioral vs. Cultural Cusps

Behavioral Cusp

Rosales-Ruiz and Baer (1997) defined “behavioral cusp” as a special instance of behavior change. According to the authors, a cusp refers to “any behavior change that brings the organism’s behavior into contact with new contingencies that have even more far-reaching consequences” (p. 533). As a matter of example, they identified crawling as a cusp because the behavior exposes the baby to new environments with a wealth of numerous and various types of contingencies that have a far-reaching impact in the development of the behavioral repertory of the baby. To classify something as a cusp is tricky, as it depends on how important the behavior is in developing new repertoires. Bosh and Fuqua (2001) argued that the concept of behavioral cusp is helpful in identifying target behaviors of significance.

Cultural Cusp

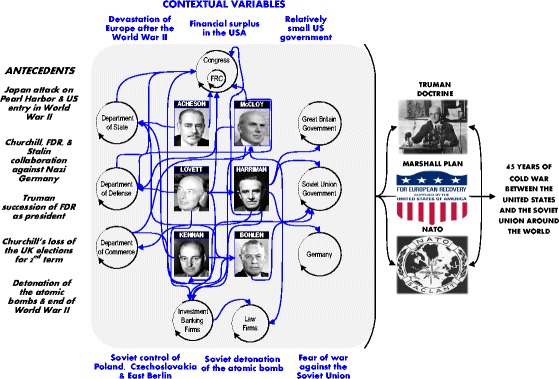

An analog to behavioral cusp in the cultural realm can be identified as “cultural cusp.” A cultural cusp refers “to nonrecurring interlocking behaviors of multiple individuals that produce an aggregate product that gives rise to significant and far-reaching cultural change.”2

Figure 2 illustrates the concept of the cultural cusp that generated the Truman Doctrine, the Marshal Plan, and NATO, three initiatives that instituted the Cold War.3 The six leaders, the “hidden architects,” are shown at the center of the figure. The connections between them represent their complex professional and personal relations. They also played multiple and influential roles in relevant metacontingencies imbedded in the US government: Congress (with its constituent Senate FRC), and several departments of the executive branch, specifically, the Departments of State, Commerce, and Defense (previously Department of War). They maintained influential relationships in investment banking firms, such Brown Brothers Harriman & Company, and law firms, such as Covington & Burling. In addition, they executed vital assignments in the governments of the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and Germany (see Table 1).

Fig. 2.

The Establishment of the Cold War, with the Truman Doctrine, The Marshall Plan and the formation of NATO as a cultural cusp. The sources of photographs included in Figure 2 are as follows: Image of Harry S. Truman. Photograph from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=14687. In public domain. Example reference: President Harry S. Truman addressing a joint session of Congress asking for $400 million in aid to Greece and Turkey. This speech became known as the "Truman Doctrine" speech, March 12, 1947. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=14687; Image of the Marshall Plan. Photograph from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Plan#/media/File:US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo.svg. In public domain. Example reference: Logo used on aid delivered to European countries during the Marshall Plan. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Plan#/media/File:US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo.svg;_Image_of_NATO; Image of NATO. Photograph from http://trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=29893. In public domain. Example reference: The official insignia of NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 07, 1952. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=29893.

Antecedent and contextual developments set the occasion for the ability of the six wise men to exert influence. Crucial antecedents were Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and the consequent US entry in World War II; Churchill, FDR, and Stalin collaboration against Nazi Germany; the appointment of Truman as US president after the sudden death of FDR; Churchill’s loss of the elections for a second term as prime minister of the UK; and the detonation of the atomic bombs in Japan that ended the war. Other contextual variables were conducive to shape the course of events for the establishment of the Cold War: the devastation of Europe after the World War II; the financial surplus in the USA; the relatively smaller size of the US government than today’s where decisions could be made faster; the Soviet control of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and East Berlin; the Soviet detonation of the atomic bomb in 1949; and the generalized fear in the USA of war against the Soviet Union (Isaacson and Thomas 1986).

The aggregate products, the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and NATO, in turn gave rise to 45 years of unprecedented and significant confrontations around the world between the USA in defense of democracy and the Soviet Union in defense of communism: in Korea with the resulting division between North and South; in Vietnam, with the war (1954–1968); in Germany, with the division between East and West and with the building of the Berlin Wall (1958–1963); in China, with its initial alliance to the Soviet Union (1945); in Israel with the confrontation of Egypt tied to the Soviet Union after the Six-Day War (June 5–10, 1967); and in Afghanistan, with the USA secretly arming Mujahedeen insurgents against the Soviet invasion (1979–1989).

The confrontations between democracy and communism expanded throughout Latin America: in Cuba, with the failed CIA-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, the beginning of over 50 years of economic blockade of the island, as well as the CIA involvement in the assassination of Che Guevara in Bolivia (1967); in Guatemala, with the ouster of Jacobo Árbenz (1954); in the Dominican Republic, with the support of troops (1965); in Chile, with the work against Salvador Allende, who was ultimately removed from power by his own government (1973); in Granada, also with military presence (1983); in El Salvador, with training and support of a ruthless regime (1979–1992); and in Nicaragua, with the support of the Contras against the leftist Sandinista government (1984).

Eventually, Mikhail Gorbachev (1981–1988) agreed to free Eastern European countries so they could determine their own destinies, remove Soviet troops from Europe, and commit to an intermediate-range nuclear forces treaty. Germany reunified and the Berlin Wall came down (1989); Lithuania obtained independence from Russia (1990). Disarmament commenced, under the maxim of trust but verify. Not surprising, after much pressure, Gorbachev resigned. And at 9 p.m. on Christmas Day, 1991, President George H. W. Bush (1924–present) addressed the nation. His speech was broadcast in 150 countries, while the Soviet flag was replaced with a new Russian flag in the Kremlin:

For over 40 years, the United States led the West in the struggle against communism and the threat it posed to our most precious values. . . .The Soviet Union itself is no more. This is a victory for democracy and freedom. . . . New, independent nations have emerged out of the wreckage of the Soviet empire. Last weekend, these former Republics formed a Commonwealth of Independent States. This act marks the end of the old Soviet Union, signified today by Mikhail Gorbachev’s decision to resign as President. (Bush 1991)

No doubt the establishment and development of the Cold War was more complex than described here, and this account might be seen as an oversimplification. As well, it could be debated who deserved more or less credit in the turn of events. However, further elaboration goes beyond the scope of this article, as the point was to illustrate how leaders impacted cultural phenomena and how their interactions and their aggregate products ended up having a tremendous impact on the world history that follows. The establishment of the Cold War constituted a cultural cusp—unique, non-reoccurring, interlocking behaviors of multiple individuals that had significant impact and brought the possibility of further and transcendent cultural change.

Conclusion

In this article, I reflected on three questions: (1) do effective leaders possess common repertoires?, (2) what is the role of the leader within complex cultural phenomena?, and (3) does the science of behavior analysis account for leadership of cultural phenomena? As part of the process of investigating these questions, I studied known leaders whose presumed accomplishments, at least on the surface, have been considerable. In examining their biographies, I found that effective leaders seem to possess common repertoires: They were all mission driven, independent thinkers, resilient, and consistent in their actions and preaching. I found that the “hidden architects” of the Cold War showed these characteristics as well. Their actions were driven by their belief that the Soviet Union’s totalitarian regime and ambitions to become a world power threatened democracy in the world and that the USA had the responsibility to contain Soviet expansion and defend liberty everywhere. They defied an isolationist foreign policy and encouraged economic trade even with countries in conflict with the USA. They were resilient in pursuing what they thought to be right for the USA and demonstrated over and over again consistency between their beliefs and their actions in government, private businesses, and social spheres. My approach and conclusions are compatible with other scholars’ (Chua and Rubenfeld 2014; Gardner and Laskin 2011; Isaacson 2009; McCain and Salter 2005; Steward 2013).

The role of leaders in complex cultural phenomena is always partial, circumstantial, and affected by the individuals’ repertoires and the behavior of others. People tend to idolize individuals and attribute to them more credit than perhaps deserved, due to a lack of consideration of existing complexity. Rest assured that there is always more to the story. Even undisputable leaders like Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela found themselves in circumstances that facilitated their accomplishments, and others helped them along the way, without whom they might not be as well known today. Margaret Mead said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” (The Insitute for Intercultural Studies 1944–2009) It is always difficult to assess if it is the leader who impacts circumstances or circumstances that make the leader. Likely, both are true. Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) said,

If there is not a war, you do not get a great general, if there is not a great occasion, you do not get the great statement, if Lincoln would have lived in times of peace, no one would have known his name now. (as cited in Brinkley 2010, chap. 10, p. 1)

It is my belief that the science of behavior analysis currently does “not” account for the leadership of cultural phenomena of large social impact like the ones illustrated in this article. Our field mainly focuses on studies and interventions involving lineages of single operant contingencies. Even interventions including many individuals affected by the same type of contingency (i.e., macrocontingencies) do not take us very far tackling complex social phenomena. This would be like trying to understand ocean currents by analyzing water molecules. Although water molecules are important, oceanographers focus on a bigger picture, taking into account the wind, water density, temperatures, gravity, salinity, earthquakes, and other variables. Studies of water molecules in the lab and the ocean currents in the natural environment are different type of phenomena. If we sit comfortably behind the notion that operant contingencies can explain everything, without attempting to understand the context, the impact of individual repertoires, and the convoluted interrelations that take place, we will be left with uninformed and superficial interpretations and recommendations.

In their outstanding work, Isaacson and Thomas (1986), like me, were simply trying to figure out how the Cold War initially came to be established with the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and the formation of NATO: “we had no ideological ax to grind, no theses to prove. Nor was it our goal to apportion responsibility for the Cold War. Instead, we sought to understand why a group of important players came to act as they did” (Isaacson and Thomas 1986, p. 32). My interest spurred from the realization that a few men engineered these initiatives that ended up leading to 45 years of some of the most significant political and military confrontations of the twentieth century. Yet, the interlocking behavior of these individuals that generated the three critical founding initiatives of the Cold War was unique, non-recurring, and nonreplicable. They had no lineage. They constituted a cultural cusp. Many cultural phenomena of far-reaching impact in society present similar characteristics and can also be studied as cultural cusps, such as the abolition of apartheid in South Africa; the independence of India from Britain; the desegregation of the bus system in Montgomery, Alabama; the formation of the Catholic congregation of Missionaries of Charity in India; the Nazi’s domination of Europe; and the creation of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

The presumed architects of the Cold War interrelated with cultural entities involved in metacontingencies, such as the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the US Congress, and the Departments of State, Commerce, and Defense (then War Department). These entities’ main aggregate products were generated by recurring interlocking behavioral contingencies of multiple individuals (i.e., culturants). They involved lineages of contingent relations between their culturants and their selecting environments. There were variations in the recurrences, such as changes in the integral interlocking behavior contingencies and/or some of the participants, due to requirements from the selecting environment. For instance, based on feedback from the US Congress, the Foreign Relations Committee might have changed some of its internal processes to increase the chances of approval of its proposals. The US Congress was the selector affecting the recurrences of the committee’s culturants. These types of cultural phenomena involving metacontingencies are abundant in society. Examples are entities that generate aggregate products through recurrent processes, such as departments or an entire companies like Apple and Berkshire Hathaway, or recurring processes across multiple entities, such federal tax collection and implementation of specific environmental regulations.

The complex nature of these types of social phenomena, involving metacontingencies and cultural cusps, raises the challenging question of whether experimental interventions are possible, leaving the possibility for prediction and control. In Beyond Freedom and Dignity, Skinner (1971) said, “Behavioral technology comparable in power and precision to physical and biological technology is lacking” (p. 5), and he also mentioned “the role of the environment has only begun to be understood, and the social environment which is a culture is often hard to identify” (p. 132). I concur. As a field, we have much to do to address complexity, in spite of the valuable work of many behavior analysts trying to advance cultural studies from a behavioral perspective (e.g., Baker, et al. 2015; Foxall 2015; Houmanfar, et al. 2015; Houmanfar, Rodrigues, and Smith 2009; Houmanfar, Rodrigues, and Ward 2010; Malagodi and Jackson 1989; Mattaini 2003a, 2003b, 2004; Pennypacker 2004; Sandaker 2009; Smith, Houmanfar, and Louis 2011; Todorov 2013; Todorov, Moreira, and Moreira 2004; Ulman 2004).

We need to figure out ways to systematically deconstruct complexity without losing sight of aggregate products and their impact. Cultural phenomena require appreciating the particulars: the interrelated behavior of the participants, the levels of decision-making, and the contextual factors affecting the complex dynamics of the events as they occur (Glenn and Malott 2004). Behavior system analysts are more likely to engage in studies of complex phenomena, as they are more like cultural engineers than pure behavior scientists (Brethower 2000; Gilbert 1996; Malott 2003; Rummler and Brache 1995). Phenomena involving metacontingencies lend to measure and control because they involve lineages of culturants. Behavior system analysts study culturants in detail through cross-functional maps and measure the impact on the selecting entity. Altering components of the culturants and measuring the impact afterwards allow for comparisons before and after interventions.

Prediction and influence are more challenging in the case of cultural cusps because the interlocking behaviors are unique and have no lineage, like the example of the establishment of the values of foreign policy at the beginning of the Cold War. In developing foreign policy, Henry Kissinger (1923–present) said, “We have to begin with an assessment of the situation as it is. If one cannot do that, one cannot make any predictions about the future” (2013, January). Later he said: “In many ways, history is the only laboratory for foreign policy. . . . By studying history, you can look at comparable situations that other societies have faced, and learn from their experience” (2013, Spring). The challenge, he argued, is to figure out comparable situations, because the players and the circumstances are always unique.

Our lack of understanding of complex phenomena as a field is perhaps why behavior analysts are rarely brought to the table to explain or intervene in events of great social importance. Instead, members of other social disciplines, including economists, political scientists, historians, psychologists, and sociologists, are sought for help (Mattaini and Luke 2014; Rumph, Ninness, McCuller, and Ninness 2005). Perhaps we could enrich our approach by collaborating with others’ disciplines that offer complementary perspectives to the study of complex systems.

Leaders’ interlocking behaviors and their aggregate products should not only be a subject of concern of behavior analysis, but the field has the responsibility to address it. If behavior analysts cannot speak about leadership and its accomplishments, what is the field’s relevance to sociocultural, political, and economic matters that affect so many? To address these issues would take many years, if not a lifetime, of study. I am comforted by the belief that our field has much to offer by bringing behavior science to cultural analysis. I am encouraged to continue in this endeavor, and it is my hope that this article stimulates others to further study and reflection on the important subject of leadership.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ramona Houmanfar for encouraging me to elaborate on leadership through various initiatives and for her feedback and support during the process. These efforts have helped me to better understand complex cultural phenomena and inspired me to continue learning. Also, I am appreciative of the participants of a 2015 think tank on cultural analysis conducted in Brazil (Todorov et al. 2015) for helping to name the type of non-replicable cultural phenomena described in this article as cultural cusp. I am indebted to Sigrid Glenn for discussions about cultural analysis concepts and interpretations. Finally, I am grateful to Majda Seuss and Thomas Breznau for early revisions of this manuscript.

Early versions of this manuscript were presented by the author as invited presentations titled Leadership and the science of behavior change, at the 40th annual convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, Chicago, IL (2014, May), and at the annual conference of the Missouri Association for Behavior Analysis, St. Louis, MO (2014, November).

Footnotes

The definition of metacontingency was discussed and agreed by a group of behavior analysts participating in a think tank on cultural analysis held in April 2015 in São Paulo, Brazil (Todorov et al. 2015, August).

The definition of cultural cusp was discussed and agreed by a group of behavior analysts participating in a think tank on cultural analysis held in April 2015 in São Paulo, Brazil (Todorov et al. 2015, August).

The sources of photographs included in Fig. 2 are as follows: Image of Harry S. Truman. Photograph from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=14687. In public domain. Example reference: President Harry S. Truman addressing a joint session of Congress asking for $400 million in aid to Greece and Turkey. This speech became known as the “Truman Doctrine” speech, March 12, 1947. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=14687; Image of the Marshall Plan. Photograph from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Plan#/media/File:US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo.svg. In public domain. Example reference: logo used on aid delivered to European countries during the Marshall Plan. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Plan#/media/File:US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo.svg; Image of NATO. Photograph from http://trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=29893. In public domain. Example reference: The official insignia of NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 07, 1952. Retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=29893.

References

- A sudden collapse: Seizure on holiday at Warm Springs. (1945, April 13). The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/1945/apr/13/secondworldwar.usa

- Acheson D. Power and diplomacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson D. Present at the creation: my years in the state department. New York: Double Day; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Afi, T. (Producer), & Morgan, J. (Director). (1994, November 8). Hell’s angel: Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Channel Four, Art series Without walls. Documentary retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJG-lgmPvYA

- Baker T, Schwenk T, Piasecki M, Smith GS, Reimer D, Jacobs N, Shonkwiler G, Hagen J, Houmanfar RA. Change in a medical school: a data-driven management of entropy. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2015;35:95–122. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2015.1035826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beisner, R. L. (2006). Dean Acheson: A life in the Cold War [Kindle DX version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com

- Bengtsson J. Aung San Suu Kyi: a biography. Dulles: Potomac Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein C. A woman in charge. New York: Random House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutto B. Daughter of destiny: an autobiography. New York: HarperCollins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bird K, Sherwin MJ. American Prometheus: the triumph and tragedy of. J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Random House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Borman W. Gandhi and nonviolence. Albany: SUNY Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bosh S, Fuqua RW. Behavioral cusps: a model for selecting target behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:123–125. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brethower DM. A systemic view of enterprise: adding value to performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2000;20(3/4):165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley A. The qualities of leadership: Dwight D. Eisenhower as warrior and president. In: Isaacson W, editor. Profiles in leadership: historians on the elusive quality of greatness [Kindle DX version] New York: W. W. Norton; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, G. (1991, December 25). Address to the nation on the commonwealth of independent states. American presidency project. Retrieved from http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=20388

- Chace J. Acheson. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chua A, Rubenfeld J. The triple package: how three unlikely traits explain the rise and fall of cultural groups in America. New York: Penguin; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, W. (1946, March 5). The sinews of peace. Speech presented at Westminster College. Fulton, MO. Retrieved from http://historyguide.org/europe/churchill.html

- Clinton HR. Living history. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton HR. Hard choices. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs M. Six months in 1945: FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman—from World War to Cold War. New York: Random House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1897, August 1). Striving of the Negro people. Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1897/08/strivings-of-the-negro-people/305446/

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1994). The souls of black folk. [Kindle DX version]. New York, NY: Dover Thrift Editions. (Originally published in 1903 by McClurg and Co. in Chicago.)

- Fisher HAL. Napoleon. Charleston: Nabu Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foxall GR. Consumer behavior analysis and the marketing firm: bilateral contingency in the context of environmental concern. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2015;35:44–69. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2015.1031426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddis JL. Cold War: New history. New York: Penguin Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddis JL. George F. Kennan: an American life. New York: Penguin Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi MK. An autobiography: the story of my experiments with truth. Mineola: Dover Publications; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner HE, Laskin E. Leading minds: an anatomy of leadership [Kindle DX version] New York: Basic Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert TF. Human competence: engineering worthy performance. Amherst: HRD Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell M. Outliers: the story of success. New York: Little, Brown and Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS. Contingencies and metacontingencies: toward a synthesis of behavior analysis and cultural materialism. The Behavior Analyst. 1988;11:161–179. doi: 10.1007/BF03392470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS. Contingencies and metacontingencies: relations among behavioral, cultural, and biological evolution. In: Lamal PA, editor. Behavioral analysis of societies and cultural practices. New York: Hemisphere Press; 1991. pp. 39–73. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS. Operant contingencies and the origin of cultures. In: Lattal KA, Chase PN, editors. Behavior theory and philosophy. New York: Klewer Academic/Plenum; 2003. pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS. Individual behavior, culture, and social change. The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:133–151. doi: 10.1007/BF03393175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS, Malagodi EF. Process and content in behavioral and cultural phenomena. Behavior and Social Issues. 1991;1(2):1–14. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v1i2.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SS, Malott ME. Complexity and selection: implications for organizational change. Behavior and Social Issues. 2004;13:89–106. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v13i2.378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herken G. The Georgetown Set: friends and rivals in Cold War Washington. New York: Random House; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchens C. The missionary position: Mother Teresa in theory and practice. New York: Verso; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Houmanfar R, Rodrigues NJ, Smith GS. Role of communication networks in behavioral systems analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2009;29(3):257–275. doi: 10.1080/01608060903092102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houmanfar RA, Rodrigues NJ, Ward TA. Emergence and metacontingency: points of contact and departure. Behavior and Social Issues. 2010;19:78–103. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v19i0.3065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]