Abstract

Using a conditional discrimination procedure, pigeons were exposed to a nonverbal analogue of qualifying autoclitics such as definitely and maybe. It has been suggested that these autoclitics are similar to tacts except that they are under the control of private discriminative stimuli. Instead of the conventional assumption of privacy, which precludes direct manipulation of the controlling variable, the autoclitic was here identified as a response that is jointly determined by its function as a modifier for the consequence of the tact and by some variable that modifies stimulus control of the tact. Following this modified conceptualization, a novel conditional discrimination procedure was developed as an analogue for establishing autoclitic-like behavior in pigeons. Under some conditions, autoclitic-like behavior was established. Methodological challenges in developing an autoclitic analogue in nonhumans are discussed, followed by a consideration of the implications of such analogues for the understanding of verbal and, more broadly, human behavior.

Keywords: Autoclitics, Verbal behavior, Conditional stimulus control, Uncertain response, Metacognition, Pigeons

Verbal behavior has been considered as operant behavior, established and maintained by reinforcement that is mediated by the listener (Skinner 1957/1992). Similar to key pecking in pigeons or lever pressing in rats in an operant chamber, verbal behavior functions as an operant, except that the reinforcer is arranged by the verbal community instead of a mechanical device. Skinner focused on the function of verbal behavior in a given environment, unlike many other scholars in his time who studied more structural aspects of language (e.g., Chomsky 1957, 1959). Skinner proposed several functions for verbal operants depending on factors such as the topography of the response and its controlling stimulus.

A tact is a class of verbal operants that is under the discriminative control of nonverbal stimuli in the physical environment (Skinner 1957/1992). For example, in teaching verbal color discrimination to a child (e.g., “green”), the parents reinforce the child’s vocalizations that resemble the sound green in the presence of the color green. If the child emits the vocal sound green in the presence of other colors, then reinforcers are withheld. As a result of reinforcement in the presence of the appropriate discriminative stimulus, the child learns to emit the correct verbal response. Analogous to the tact, nonhuman animals can be trained to discriminate colors under a conditional discrimination procedure (e.g., Berryman et al. 1963). These responses are not vocal, but functionally, they may be considered as an analogue of the tact.

An issue arises when teaching another class of verbal operant called an autoclitic, which is a verbal response “that is based on or depends upon other verbal behavior” (Skinner 1957/1992 p. 315). Several types of autoclitic were proposed by Skinner, with subtypes in each. Of interest in the present analysis is the qualifying autoclitic, which qualifies other verbal response “in such a way that the intensity or direction of the listener’s behavior is modified” (p. 322), in particular, the subtype that implies “certainty,” such as definitely and maybe (hereafter, the term autoclitic refers only to these qualifying autoclitics). These autoclitics usually occur with other verbal operants including tacts (e.g., “maybe green”). It remains unclear, however, how they are acquired, because private events such as “certainty” have been suggested to be involved. Autoclitics have been considered to be similar to tacts except that autoclitics are under the stimulus control of private rather than public events (Catania 1980, 1998; Skinner 1957/1992). Skinner (1957/1992), for example, noted that the autoclitic indicates “the speaker’s inclination… with respect to the subject under consideration” (p. 328) and Catania, in a speculation about how to develop a procedure for the study of autoclitic-like behavior with animals, observed:

[S]uppose we arrange a series of discrimination trials ranging from easy to hard for a pigeon’s key pecks and then try teaching the pigeon to report its certainty after each trial. We could add two new keys to the chamber, designating one as the certain key and the other as the uncertain key. …The trouble is that we have to know whether the pigeon is certain or uncertain in each discrimination trial before we can reinforce pecks on one or the other of the new keys appropriately. This is again the problem of teaching a tact of a private event. (Catania 1998, p. 259; italics were in the original text)

The assumed role of private events in controlling autoclitics poses both conceptual and practical issues. On the practical side, such a role precludes establishing precise discriminations because, unlike the above example of the tact, the verbal community does not have access to the variable controlling the autoclitics (i.e., the discriminative stimuli). It has been suggested that the community instead may rely on some public event (e.g., facial expression or behavioral history, if it is known [e.g., “expertise”]) assumed to be similar to or correlated with a given private event (Skinner 1945, 1992/1957). Yet such a correlation is not guaranteed. On the conceptual side, the assumed role of private events in their development and occurrence precludes empirical analyses of autoclitics. Unless the controlling variable is accessible to the researcher, such an analysis is impossible. Thus, the behavioral processes related to the development and occurrence of autoclitics remain elusive. If private events of whatever character are assumed to control the production of autoclitics, then also precluded is the study of nonverbal analogues of the autoclitic with nonhuman animals, leaving unclear whether the difference between verbal and nonverbal responses is merely structural or fundamental. More broadly, the nature of the difference between the two types of behavior relates to the issue of the principles governing human and animal behavior (e.g., Horne and Lowe 1993; Lowe et al. 1983; Madden and Perone 1999). The assumed role of private events in controlling autoclitics leaves these important questions unanswered and, indeed, empirically unanswerable.

Experimental analyses of autoclitics and their nonverbal analogues may be possible with a different conceptualization of the variables controlling them. A promising approach is to focus on their function in the context where they occur, regardless of whether that context is internal or external to the organism. The function of autoclitics, as noted above, is to modify “the intensity or direction of the listener’s behavior” (Skinner 1957/1992, p. 322). This function can be interpreted to mean that the magnitude, immediacy, or quality of the consequence of a verbal operant (e.g., a tact) are conditional relative to the autoclitic in question. Table 1 shows an example of such a conditional relation in which the consequence of the tact varies depending both on whether the tact is correct or incorrect and on what autoclitic occurs with the tact: A reinforcer is presented upon a correct tact but its magnitude may be large or small, respectively, depending on whether definitely or maybe accompanies the tact; a punisher is presented upon an incorrect tact but its magnitude may be large or small, respectively, with definitely and maybe.

Table 1.

An example of a conditional relation between the autoclitic and the consequence of tact

| Tact | Autoclitic | |

| Definitely | Maybe | |

| Correct | Large reinforcer | Small reinforcer |

| Incorrect | Large punisher | Small punisher |

In the actual experiment, four different durations of reinforcement were set for the cells in the matrix: 9- and 3-s access to food for the correct tact upon a definitely and a maybe response, respectively; 0- and 1.5-s access to food for the incorrect tact upon the respective responses

Conditional relations similar to the preceding example may be present when autoclitics are acquired. Faced with such a complex contingency, humans might emit the autoclitic definitely when they are more likely to make a correct tact (i.e., stronger stimulus control) because its emission increases the magnitude of the reinforcer. Likewise, they might emit the autoclitic maybe when they are more likely to make an incorrect tact (i.e., weaker stimulus control) because its emission reduces the magnitude of the punisher. Conceptualized this way, these autoclitics are identified with observable responses occurring in a conditional contingency, not with tacts of private events, like “certainty” (cf. Baum 1993, 2011; Zuriff 1975). Specifically, they are determined jointly by how they modify or modulate the consequence of the tact and some variable that affects stimulus control of the tact (e.g., delays to the opportunity to make a choice response). Unlike private discriminative stimuli, these variables are subject to manipulation, making it possible to study autoclitics empirically.

The goal of the present study was to examine an experimental analogue of the “externalized autoclitic” by attempting to establish autoclitic-like responses (labeled here as definitely and maybe) in pigeons under a delayed conditional discrimination procedure based on the analysis shown in Table 1. Instead of imposing a punishment contingency on incorrect tacts, however, only reinforcement contingencies were in effect for both correct and incorrect tacts, although the reinforcer magnitude was relatively smaller for the latter. Within incorrect tacts, the reinforcer magnitude was smaller with the definitely than with the maybe response. Three criteria had to be met for a particular response to qualify in this study as an autoclitic. First, autoclitics are sensitive to reinforcer magnitude. Second, the autoclitic varies as a function of the strength of stimulus control of the tact. Third, the maybe response occurs when the stimulus control of the tact is weak because its occurrence prevents the smallest reinforcer magnitude (0-s access to food). The first criterion was tested by manipulating reinforcement duration, the second by varying the delay interval in the conditional discrimination task, and the third by removing the opportunity to prevent the shortest reinforcement duration. Upon meeting all the three criteria, a response was considered to qualify as a nonverbal analogue of the autoclitic.

Method

Subjects

Four White Carneau pigeons served. The pigeons had previously been exposed to a number of different contingencies. Each was maintained at 80 % of its ad libitum body weight by feedings, when necessary, at least 30 min after a session ended. The pigeons were housed individually in the home cage with continuous access to water and health grit in a vivarium maintained under a 12 h light: 12 h dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m.).

Apparatus

Two almost identical operant conditioning chambers, each with a work area 30 cm long by 38 cm high by 32 cm wide, were used. The front wall of the chamber was an aluminum work panel containing three 2-cm diameter response keys, each operated by a minimal force of 0.15 N. The keys were mounted horizontally 9 cm apart from each other, 27 cm above the floor, and each could be transilluminated by a red, green, and white 28-vdc bulb. A white houselight was located at the lower right corner of the work panel. Reinforcement was access to mixed grain from a hopper, which was located behind a 4.5-cm-high by 5.5-cm-wide aperture mounted in the midline of the front wall, with its lower edge 9 cm above the floor. During reinforcement, all the lights were extinguished, and the hopper was raised into the aperture, which was illuminated by a white light during feeder operation. White noise masked extraneous noise. A Dell® computer, located in the adjacent room, operated MED-PC® software (version IV) which in turn controlled the experiment and recorded the data.

Procedure

General Procedure

Three features were common across all conditions. First, each session commenced with a 60-s blackout; thereafter, the houselight remained on throughout the session except during reinforcement and intertrial intervals (ITIs). Second, programmed ITIs were 15, 20, or 25 s at random without replacement. When reinforcement occurred, however, the ITI was shortened by subtracting the reinforcement duration from a programmed ITI. For example, when a programmed ITI was 15 s and reinforcement duration was 3 s in a given trial, the actual ITI was 12 s. Third, sessions occurred approximately at the same time of the day, 7 days a week, with only rare exceptions.

Preliminary Training 1

Color discrimination (the tact) first was trained in a conventional delayed conditional discrimination procedure incorporating sample, delay, and choice components. During the sample component, the center key was either red or green with p = 0.5. A fixed number of responses (five for Pigeons 007, 840, and 4141; ten for Pigeon 999) on the key turned off the key light, initiating a delay component. The delay was set at 0 s in the first preliminary training condition so that the sample component was immediately followed by a choice component during which the left key was either red or green, with p = 0.5, while the right key was the opposite color. A correct tact was operationally defined as three consecutive pecks on a side key illuminated the same color as the sample stimulus; a switch from one choice key to another during a response run on one of the keys reset the response requirement. A correct tact resulted in 3-s access to food. This was followed by an ITI and then by the next new trial. An incorrect tact led directly to an ITI and, subsequently, to a correction trial during which the previous noncorrection trial was replayed in all aspects until a correct tact was made. Each session ended when 60 noncorrection trials were completed. This training lasted until the percentage of correct tacts (i.e., the number of correct tacts divided by the number of noncorrection trials) was consistently above 80.

Preliminary Training 2

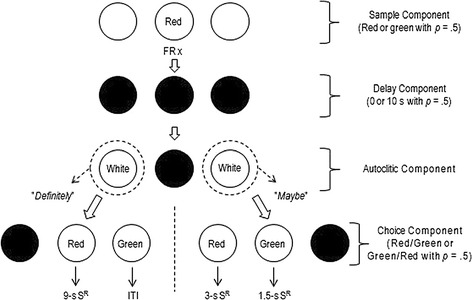

The delayed conditional discrimination procedure shown in Fig. 1 was in effect in the second preliminary training condition. The sample and delay components remained as in the first. A component (hereafter described as the “autoclitic component”) was added between the delay and choice components. A forced-choice procedure was in effect during the autoclitic component throughout this training: One of the side keys was white with p = 0.5 while the other side key was dark and inoperative. A single response on the lit key turned off the key light, initiating the choice component.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the present procedure. FR identifies a fixed-ratio schedule of x responses (which varied across pigeons), S R indicates a reinforcer, and ITI identifies an intertrial interval

On a left autoclitic-component response, only the center and right keys were operative during the choice component. The center key was either red or green with p = 0.5 while the right key was the opposite color. Likewise, upon a right autoclitic-component response, only the center and left keys were operative during the choice component, and the center key was either red or green with p = 0.5 while the left key was the opposite color. Regardless of the side of the autoclitic-component response, a correct tact resulted in 3-s food access, which was then followed by an ITI. An incorrect tact led directly to an ITI and then to a correction trial during which the preceding noncorrection trial was replayed in all aspects until a correct tact was emitted. Each session consisted of 48 noncorrection trials. This condition lasted until percent correct tacts remained above 80 for two consecutive sessions with each side of the autoclitic-component response.

Preliminary Training 3

The third preliminary training condition was similar to the second except as follows. First, each session consisted of eight blocks of six trials (48 trials total). Second, the forced-choice procedure used in the autoclitic component described above was in effect only in the first two trials of each block; the subsequent four trials were free-choice trials where both side keys were white. Third, when a tact was incorrect during the free-choice trial, a correction trial after an ITI repeated the preceding noncorrection trial in all but one aspect: In the autoclitic component, only the side key that was pecked in the preceding noncorrection trial was illuminated and operative; thus, effectively, the choice was forced. This third training condition lasted until the frequency of autoclitic-component responses stabilized on each side, as assessed by visual inspection. Table 2 shows a sequence of conditions subsequent to the third preliminary training condition for each pigeon, along with the set of parameters used in each condition.

Table 2.

Sequence of conditions for each pigeon with the value in parentheses indicating the number of sessions (top) and a set of the parameter of variables used in each condition (bottom)

| Pigeon | ||||||

| Sequence | 4141 | 007 | 840 | 999 | ||

| Test for sensitivity to reinforcement duration | ||||||

| 1. | Type 1 (4) | Type 2a (3) | Type 3 (7) | Type 2 (4) | ||

| 2. | Type 2 (7) | Type 3a (3) | Type 3 (11) | |||

| 3. | Type 3 (12) | Type 3 (6) | ||||

| Experimental conditions | ||||||

| 1. | Baseline (33) | Baseline (12) | Baseline (13) | Baseline (16) | ||

| 2. | Delay (14) | Delay (12) | Delay (30) | Delay (22) | ||

| 3. | Control (26) | Control (25) | Control (48) | Control (16) | ||

| 4. | Delay (29) | Delay (43) | Delay (24) | |||

| 5. | Control (17) | |||||

| 6. | Delay (35) | |||||

| Side of maybe response | Left | Right | Left | Left | ||

| Reinforcement duration | ||||||

| Definitely response | Maybe response | Correction procedure | ||||

| Condition | Delay | Correct | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | |

| Test for sensitivity to reinforcement duration | ||||||

| Type 1 | 0 s | 6 s | 0 s | 0 s | 0 s | Present |

| Type 2 | 0 s | 6 s | 0 s | 3 s | 0 s | Present |

| Type 3 | 0 s | 9 s | 0 s | 3 s | 0 s | Present |

| Experimental conditions | ||||||

| Baseline | 0 s | 9 s | 0 s | 3 s | 1.5 s | Absent |

| Delay | 0 and 10 s | 9 s | 0 s | 3 s | 1.5 s | Absent |

| Control | 0 and 10 s | 9 s | 0 s | 3 s | 0 s | Absent |

aThe side of the “maybe” response was the opposite to the one shown in the table

Test for Sensitivity to Reinforcement Duration

This condition was a test for the first criterion for an autoclitic noted in the introduction—that the autoclitic is sensitive to reinforcer magnitude. As in the third preliminary training condition, each session consisted of eight blocks of six trials; the forced-choice procedure used in the autoclitic component was in effect during the first two trials of each block; and the correction procedure for incorrect tacts was in effect. Unlike the preceding condition, depending on the side of the autoclitic-component response, a correct tact resulted in longer or shorter access to food. These responses hereafter are described as definitely and maybe responses. The reinforcement duration for correct tacts was varied, as shown in Table 2, between 0 and 9 s in different conditions (labeled “Type 1,” “Type 2,” and “Type 3”) to determine if the autoclitic-component response would track the longer reinforcement duration during free-choice trials. This condition remained in effect until the frequency of maybe responses during free-choice trials was stable by visual inspection or until their frequency had a clear trend to either direction.

Baseline

This condition was similar to the previous one in which sensitivity to reinforcement duration was tested except the correction procedure was no longer in effect, and a correct or incorrect tact, respectively, resulted in 9- or 0-s food access upon a definitely response and in 3- or 1.5-s food access upon a maybe response. This condition was included to assess the effect of having the 1.5-s reinforcement contingency on the autoclitic-component response. It also served as a baseline prior to the manipulation of the duration of delay to the onset of choice component. This condition was in effect until the frequency of maybe responses during the free-choice trials was considered stable by visual inspection.

Delay Condition

This condition was a test for the second criterion for an autoclitic noted in the introduction—that the autoclitic varies as a function of the strength of stimulus control of the tact. The procedure was similar to that in the baseline condition except that the delay interval was either 0 or 10 s with p = 0.5 in a given trial. The number of trials with these two delay intervals was equated within a session such that there were 8 forced-choice and 16 free-choice trials for each delay interval in a session. During the 10-s delay, only the houselight remained on. This condition was in effect until the frequency of maybe responses stabilized for each delay interval during the free-choice trials, as assessed by visual inspection.

Control Condition

This condition was a test for the third criterion for an autoclitic noted in the introduction—that the maybe response occurs when stimulus control of the tact is weak because its emission prevents the smallest reinforcer magnitude. The procedure was similar to that in the delay condition except that, upon a maybe response, an incorrect tact resulted in 0-s, not 1.5-s, access to food. The stability criterion was as in the third condition.

Results

The analysis reported here was based on the data from noncorrection trials. Figure 2 shows the frequency of maybe responses of each pigeon during free-choice trials over the last six sessions of successive conditions. Data are presented separately for the 0- and 10-s delay trials. In the test condition for sensitivity to reinforcement duration and the baseline condition, where the delay was 0 s, data were still collected as if there were 0- and 10-s delay trials in a session (i.e., a half of the trials were randomly designated as “10-s delay trials” only for purposes of data collection although they actually were 0-s delays). When the reinforcement duration for a correct tact was varied during the test condition, autoclitic-component responses generally were sensitive to this variable. For example, when the definitely and maybe response could result, respectively, in 6- and 0-s access to food (the Type 1 reinforcer duration combination), Pigeon 4141 showed few maybe responses by the end of the condition. After the reinforcement duration for a correct tact upon a maybe response was changed from 0 to 3 s (the Type 2 reinforcer duration combination), this pigeon was more likely to emit the maybe response. This suggests a bias toward the (left) key for the maybe response if there was no difference in the reinforcement durations between the definitely and maybe responses. After the duration associated with a definitely response was changed from 6 to 9 s (the Type 3 reinforcer duration combination), there again were few maybe responses. Pigeon 4141’s autoclitic-component responses thus were sensitive to the reinforcement duration. This sensitivity also was evident in the autoclitic-component responses of the other pigeons, with the possible exception of Pigeon 840. (This latter observation is the case even though a pilot study, conducted in between the third preliminary training and the Type 3 reinforcer duration test condition, revealed sensitivity of the autoclitic-component responses of Pigeon 840 to reinforcement duration. Data from the pilot study are not presented in Fig. 2 because they are not directly comparable to that from the Type 3 reinforcer duration test condition given differences in the parameter of more than one variable.) Overall, a threefold difference in reinforcement duration (9 and 3 s) was necessary between the definitely and maybe response to establish that the autoclitic-component response was sensitive to this variable.

Fig. 2.

The frequency of maybe responses during free-choice trials over the last six sessions of successive conditions (some conditions had less than six sessions). Empty and filled circles represent 0- and 10-s delay trials, respectively, although the delay duration was kept at 0 s in the test condition for sensitivity to reinforcement duration and the baseline condition. Type 1 is the condition where a correct tact resulted in a 6- and 0-s food access upon a definitely and maybe response, respectively; Type 2 is the condition where a correct tact resulted in a 6- and 3-s food access upon the respective responses; Type 3 is the condition where a correct tact resulted in a 9- and 3-s food access upon the respective responses; and asterisks indicate that, in these conditions, the side of maybe response was the opposite to that in the rest of the conditions. See Table 1 for other parameters

Figure 2 shows that, during the baseline condition, where an incorrect tact upon on a maybe response led to 1.5 s of food access, maybe responses increased either slightly or not at all relative to the last session or two of Type 3 reinforcer duration test condition. When a delay condition was in effect for the first time, the maybe response was more likely in the 10-s than 0-s delay trials in each pigeon. Moreover, as described in more detail below, the higher frequency of maybe responses with 10-s delays was associated with lower accuracy of tacting relative to the tacting that occurred with 0-s delays. Thus, the behavior of all four pigeons during the delay condition confirmed the second criterion for an autoclitic, that is, that the autoclitic response varies as a function of the strength of stimulus control of the tact. When a control condition was in effect for the first time, in which an incorrect tact upon a maybe response resulted in 0-s food access, maybe responses following the 10-s delay decreased relative to the preceding delay condition for Pigeons 4141, 007, and 840. The behavior of these pigeons thus confirmed the third criterion for an autoclitic that the maybe response occurs when the stimulus control of the tact is weak because its occurrence prevents the smallest reinforcer magnitude.

To this point in the experiment, three of the four pigeons met each of the three criteria for autoclitics. Thus, it is concluded that they showed autoclitic-like behavior. Yet, when the second delay condition followed the (first) control condition, only Pigeon 4141 showed an increase in maybe responses (see Fig. 2). Subsequently, this pigeon showed a decrease in these responses when the second control condition was in effect. Pigeon 4141, however, failed to increase maybe responses during the third delay condition.

Figure 3 shows the mean percentage of correct tacts across successive conditions averaged over the last six sessions of each condition. Data are presented separately for the free- and forced-choice trials (left and right panels) and for the definitely and maybe response (dashed and solid lines). The data also are presented separately for the 0-s and 10-s delay trials (empty and filled circles). Some data points are missing from the left panel—when the autoclitic-component response was exclusive to one of the side keys during free-choice trials. Accuracy generally was highest upon the definitely response following 0-s delays in both free- and forced-choice trials. When the 10-s delay was introduced during the transition from the baseline to the first delay condition, accuracy associated with the definitely response decreased in both free- and forced-choice trials in each pigeon and generally remained low in the subsequent control and delay conditions. Likewise, upon the maybe response, accuracy generally was higher in the 0-s than in the 10-s delay trials when a delay condition was in effect for the first time. In the subsequent conditions, however, the accuracy difference between the two delay durations was less systematic (e.g., Pigeon 007). Overall, the results suggest that the strength of stimulus control of the tact varied as a function of delay durations, indicating a successful manipulation of its strength with the delay duration.

Fig. 3.

The mean percentage, averaged over the last six sessions at each condition, of correct tacts during free-choice trials (left panel) and during forced-choice trials (right panel) across successive conditions. For the test condition for sensitivity to reinforcement duration, only the data from Type 3 are presented. Some data points are missing from the left panel because the autoclitic-component response was exclusive on one of the side keys in some conditions so that no data were available. Dashed and solid lines represent trials in which a definitely and maybe response was emitted, respectively. Empty and filled circles represent trials in which the delay duration was 0 and 10 s, respectively

Discussion

The present study was an attempt to establish behavior in pigeons using a conditional discrimination procedure that is analogous to the human verbal autoclitic. Unlike the conventional view that private events serve as the discriminative stimulus for the autoclitic (Catania 1980, 1998; Skinner 1957/1992), it was here considered to be a response that was jointly determined by two observable variables, namely, its function as a modifier for the consequence for tact and the delay between a sample and the opportunity to tact that sample. In this study, a key peck would be considered to qualify as a nonverbal analogue of an autoclitic if three criteria were met: that the key peck (a) was sensitive to reinforcement duration; (b) varied as a function of the strength of stimulus control of the tact; and (c) varied as such only when the maybe response prevented the shortest reinforcement duration. Among the four pigeons, three met each of these criteria at least once. Only one of the three, however, met the third criterion across several replications, and even this pigeon failed to meet it in the last condition. The result is, thus, suggestive rather than conclusive that autoclitic-like behavior can be established in pigeons. The fact that there was control of autoclitic-like responding for some of the pigeons during at least some of the conditions suggests the utility of the logic of the general analogue outlined to “objectifying” the study of autoclitic-like behavior in nonhuman species.

Further refinement of the procedure through modifying some of its parameters might yield greater control and, thus, more systematic evidence for the autoclitic analogue. A criticism can arise, for example, from the experimental result that accuracy of color discrimination often was around a chance level (i.e., 50 %) in the 10-s delay trial during the delay and control conditions. This chance-level accuracy indicates that responses in the choice component were not under the discriminative control of sample stimulus in these trials, which suggests that pigeons were not really tacting anything, but rather were emitting definitely and maybe responses independently of the antecedent stimuli. In the absence of the tact, these autoclitic responses cannot modify its consequence and the logic of the present procedure breaks down. This issue may be resolved, however, by using shorter delay intervals than 10 s. In a conventional delayed conditional discrimination procedure, accuracy is often at a chance level with such a long delay as 10 s but can be maintained at a higher level with a relatively short, nonzero delay interval (e.g., Berryman et al. 1963). Similarly in the present procedure, there could have been some level of discriminative control by the sample stimulus if relatively short delays were used, providing evidence for the copresence of tact and autoclitic analogues. The challenge, thus, is to find an appropriate parameter for the delay that increases the frequency of maybe responses and also decreases discrimination accuracy.

Greater control also may be achieved by modifying the parameter of the consequence of color discrimination. The response in the autoclitic component was sensitive to reinforcement duration, consistent with previous research on reinforcer magnitude using conventional concurrent and concurrent-chain schedules (e.g., Bonem and Crossman 1988; Catania 1963; Grace 1995). Even so, a threefold difference (i.e., 9 vs. 3 s) was necessary between the definitely and maybe responses; otherwise, the autoclitic-component response did not track the larger reinforcer in the test condition for sensitivity to reinforcement duration. The necessity of the threefold difference, in turn, restricted the range of reinforcement durations that could be used for an incorrect tact upon a maybe response. The duration was set at 1.5 s to differentiate from that for correct tact upon a maybe response (i.e., 3 s) and also from that for incorrect tact upon a definitely response (i.e., 0 s). But their functional differences were unclear and, if the differences were small, that could have contributed to the failure of some pigeons in meeting the third criterion regarding the qualification for autoclitics. It was possible to conduct an independent assessment of their reinforcing effects, for example, by examining the choice between 0- and 1.5-s food accesses. Yet it may be inappropriate to extrapolate such an assessment result to the present procedure.

It also is possible that the set of parameters for the reinforcement duration was less than optimal. If the pigeon randomly pecked choice keys in the choice component and made correct tacts in half of the trials, it would earn a mean of 4.5- and 2.25-s access to food following the definitely and maybe response, respectively. This mean difference could have favored the emission of definitely over maybe responses, regardless of the strength of stimulus control of color discrimination, which may explain low frequencies of maybe responses in some of the pigeons. Yet such an analysis needs to take into account the probability of reinforcement. Some probability-discounting research reveals that an alternative resulting in a smaller reinforcer magnitude at a higher probability can be preferred over the alternative that leads to a larger reinforcer magnitude at a lower probability depending on the parameter of the variables (e.g., Rachlin et al. 1991). This does not necessarily mean that the parameter of reinforcement duration was selected appropriately in the present study; rather, it suggests caution in the parameter selection. Alternatively, a punishment contingency could be arranged for incorrect tacts as depicted in Table 1. In this case, the probability of either reinforcement or punishment for color discrimination is fixed at 100 %, controlling one of the variables possibly relevant for autoclitics. Moreover, arranging such a punishment contingency for an incorrect tact introduces potentially stronger aversive consequences than 0-s food access, thereby allowing a wider range in the parameter of the consequence for an incorrect tact.

Despite the above methodological issues, the present study was, to the knowledge of the authors, the first attempt to empirically study autoclitic-like behavior with nonhuman animals. Previous analyses of autoclitics have been predominantly theoretical, presumably due to the assumed role of private events (see Howard and Rice 1988, who trained preschool children a different subtype of qualifying autoclitic like using public stimuli that they assumed were correlated with private stimuli). Although different from the original conceptualization of the autoclitic proposed by Skinner (1957/1992) in that it bypasses private events as the basis for autoclitics, the present reconceptualization seems to have value because it allows the possibility of the experimental analysis of the contingencies operating on this type of verbal behavior.

The establishment of procedures for studying verbal and nonverbal behavior on a common ground is a necessary step for determining the nature of differences between the two types of behavior. Some researchers have assigned a special role to verbal behavior in human behavior, arguing that there is a fundamental difference in the principles governing human and animal behavior (Horne and Lowe 1993; Lowe et al. 1983). For example, when placed in a fixed-interval (FI) schedule, human infants, prior to the appearance of verbal behavior, showed a scalloped pattern of responding as typically observed in nonhuman animals (Lowe et al. 1983) but adult humans showed either a high rate of responding with brief postreinforcement pauses or a very low response rate (e.g., Weiner 1969). Such a difference in the schedule-controlled behavior across different ages has been attributed to the development of verbal behavior (Lowe 1979). Instructions can affect operant behavior (e.g., Catania et al. 1982; Galizio 1979; Matthews et al. 1977), but this is not direct evidence that verbal behavior is fundamentally different from nonverbal behavior in terms of the process governing them. A common ground is necessary for verbal and nonverbal behavior to determine if the two are affected similarly by a set of the same variables. The present study proposes one method for establishing such common ground.

The autoclitic as defined here is conceptually related to the notion of an “uncertain” response studied in other contexts (e.g., Inman and Shettleworth 1999; Smith et al. 1995). Inman and Shettleworth, for example, presented a choice key in a delayed conditional discrimination procedure in addition to other choice keys, each associated with a sample stimulus. A response on the additional choice key always produced a reinforcer but its magnitude was smaller than that for correct choice. The response on this key increased as a function of the delay duration, thereby serving as an “I don’t know” or uncertain response effectively. The autoclitic—the maybe response in particular—may be considered as an uncertain response that is followed by a tact. It is worth noting that the uncertain response has been interpreted as metamemory or, more broadly, metacognition, and autoclitics can also be viewed as such. From the perspective of an operant analysis of autoclitics, metacognition may be identified with observable behavior that occurs under a complex contingency. Using procedures like the ones described in this experiment, it then seems feasible to bring into the realm of behavior analysis a rather general construct of some importance in the worldview of cognitive psychology.

In summary, the present study provides suggestive evidence for autoclitic-like behavior in pigeons. A major advantage of the present conceptualization of autoclitics is to render the analysis of private events unnecessary, thereby allowing the possibility of experimental analysis. Although refinement is necessary, the present procedure could be applied with both human and nonhuman animals. The study of autoclitics across different species may contribute not only to a better understanding of human verbal behavior, but also to an understanding of how verbal functions have evolved.

Footnotes

The research was conducted under a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at West Virginia University and was supported by a Student Research Grant from Verbal Behavior SIG to Toshikazu Kuroda. Portions of these data were presented at the 37th annual meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, 2011, Denver, CO.

References

- Baum WM. The status of private events in behavior analysis. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1993;16:644. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00032064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baum WM. Behaviorism, private events, and the molar view of behavior. Behavior Analyst. 2011;34:185–200. doi: 10.1007/BF03392249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman R, Cumming WW, Nevin JA. Acquisition of delayed matching in the pigeon. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:101–107. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonem M, Crossman EK. Elucidating the effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.104.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Concurrent performances: a baseline for the study of reinforcement magnitude. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:299–300. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Autoclitic processes and the structure of behavior. Behaviorism. 1980;8:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Learning. 4. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC, Matthews BA, Shimoff E. Instructed versus shaped human verbal behavior: interactions with nonverbal responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1982;38:233–248. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1982.38-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. A review of B.F. Skinner’s verbal behavior. Language. 1959;35:26–58. doi: 10.2307/411334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galizio M. Contingency-shaped and rule-governed behavior: instructional control of human loss avoidance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1979;31:53–70. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1979.31-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace RC. Independence of reinforcement delay and magnitude in concurrent chains. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995;63:255–276. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.63-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF. Determinants of human performance on concurrent schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1993;59:29–60. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.59-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JS, Rice DE. Establishing a generalized autoclitic repertoire in preschool children. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1988;6:45–59. doi: 10.1007/BF03392828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman A, Shettleworth SJ. Detecting metamemory in nonverbal subjects: a test with pigeons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1999;25:389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe CF. Determinants of human operant behaviour. In: Zeiler MD, Harzem P, editors. Advances in analysis of behaviour (Vol. 1). Reinforcement and the organisation of behavior. Chichester: Wiley; 1979. pp. 159–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe CF, Beasty A, Bentall RP. The role of verbal behavior in human learning: infant performance on fixed-interval schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1983;39:157–164. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1983.39-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Perone M. Human sensitivity to concurrent schedules of reinforcement: effects of observing schedule-correlated stimuli. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1999;71:303–318. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BA, Shimoff E, Catania CA, Sagvolden T. Uninstructed human responding: sensitivity to ratio and interval contingencies. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1977;27:453–467. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.27-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Raineri A, Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;55:233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. The operational analysis of psychological terms. Psychological Review. 1945;52:270–277. doi: 10.1037/h0062535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Cambridge: B. F. Skinner Foundation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Schull J, Strote J, McGee K, Egnor R, Erb L. The uncertain response in the bottlenosed dolphin (Tursiops truncates) Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1995;124:391–408. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.124.4.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner H. Controlling human fixed-interval performance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1969;12:349–373. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuriff GE. Where is the agent in behavior? Behaviorism. 1975;3:1–21. [Google Scholar]