Abstract

The stimulus pairing observation procedure (SPOP) combined with multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) has been shown to be effective with typically developing preschoolers in establishing the joint stimulus control required for the development of naming. The purpose of the current investigation was to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of the SPOP in establishing speaker and listener responses in children with autism. Participants were presented with pairings of auditory and visual stimuli during instruction. Participants’ tacting and listener responses of the visual stimuli were then evaluated during a test phase. MEI with novel pairs of auditory and visual stimuli was conducted if participants did not demonstrate criterion performance on tact and listener probes. SPOP in conjunction with MEI was shown to be effective in establishing some of the tact and listener relations for the three participants. However, accuracy on tact probes was always lower than listener probes. The participant who responded with the highest accuracy on untaught tact and listener probes also displayed echoic responding on the lowest proportion of SPOP instruction and listener test trials.

Keywords: Stimulus pairing observation procedure, Multiple exemplar instruction, Verbal behavior, Autism

Typically developing children readily acquire tact and listener repertoires without formal instruction at a young age. Following the establishment of certain prerequisite skills, only one response topography (e.g., a tact) needs to be directly taught for the other response topography to emerge (e.g., a listener response). In their identification of naming as a higher order operant, Horne and Lowe (1996) provide a detailed account of how this may occur naturalistically. Specifically, Horne and Lowe (1996) describe naming as involving “the establishment of bidirectional or closed loop relations between a class of objects and events and the speaker-listener behavior they occasion” (p. 200). Naming thus occurs when a child responds to classes of stimuli as both a speaker and a listener. Necessary components of the name relation include listener responding, echoic behavior, and tacting. For example, in the presence of a dog, a caregiver may instruct a child to “look at the dog,” which may occasion the child’s orienting to, pointing to, or even selecting a stuffed toy dog from an array of other stimuli. As the child’s echoic repertoire develops, she may begin echoing the caregiver’s dictation of the name “dog,” such that the child’s own utterance comes to occasion his or her own orienting to, pointing to, or selection of, the stimulus dog. Finally, various exemplars of dogs may then come to be discriminative for the child’s tacting of dogs, responses which are likely to facilitate further listener behavior on part of the child (Horne and Lowe 1996).

Several basic laboratory studies conducted with young children have focused on the role of naming and stimulus categorization (e.g., Lowe et al. 2002; Horne et al. 2004). Lowe et al. (2002), for example, taught typically developing children to tact arbitrary stimuli. Categorization and corresponding listener skills were shown to emerge in the absence of explicit reinforcement following tact instruction. Contrarily, Horne et al. (2004) evaluated the effects of teaching listener responses only on children’s tacts and categorization, and found that teaching listener responding did not result in the emergence of categorization or the corresponding tact repertoire. These results are consistent with the notion of echoic, tact, and listener responding as the basic components of the name relation.

Children with language delays or developmental disorders may be missing some of the prerequisite components of naming, making it necessary to directly teach each repertoire and program explicitly for naming. Research by Greer and colleagues has focused on doing just this, often utilizing multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) to directly establish the necessary speaker and listener repertoires by providing instruction with multiple stimulus sets. For example, Fiorile and Greer (2007) reported that listener responding did not emerge following tact instruction in children with autism until participants received MEI for both speaker and listener components with various novel stimuli. Following MEI, participants showed untaught listener responses with the initial instructional stimuli, and listener responding with novel stimulus sets was also shown to emerge following tact instruction alone. The authors underscore the valuable role MEI may play in promoting the development of the requisite skills constituting the name relation. Likewise, Greer et al. (2007) compared the efficacy of instruction with single, versus multiple, exemplars in promoting the necessary components of naming and found that only participants who received MEI displayed a naming repertoire upon conclusion of the study.

Interestingly, many incidental learning opportunities involve the simple pairing of visual stimuli and their corresponding names dictated by caregivers. Movies, television, computer games, and sound-activated toys are just a few examples of how such stimulus pairing may be presented. Additionally, everyday discourse by caregivers undoubtedly contains many learning opportunities of this kind. Although there is little doubt that caregivers differentially reinforce a child’s listener, echoic, and tacting responses in certain circumstances, it seems plausible that at times children may simply need to see visual stimuli and hear their accompanying names in order to display some of the untaught skills Horne and Lowe (1996) discuss. In other words, simply hearing the pairing of a caregiver’s dictation of “dog” along with several exemplars of dogs may be sufficient for the child to be able to tact and identify dogs. This possibility has been investigated by a group of researchers using a procedure known as the stimulus pairing observation procedure, or SPOP (e.g., Smyth et al. 2006), who have found that exposing participants to repeated pairings of auditory and visual stimuli can promote the emergence of untaught responses. With these procedures, the presentations of auditory and visual stimuli are typically separated by an intertrial interval (ITI) between the presentations of pairs of stimuli. Leader and Barnes-Holmes (2001a and b) showed that SPOP was effective in promoting visual-visual derived relations (fraction-decimal) in typically developing children. SPOP may be a good laboratory model of how language develops naturalistically, because it mirrors learning opportunities that children encounter as they watch adults and other children tact and interact with stimuli.

Rosales et al. (2012) implemented the SPOP with preschool-age typically developing children who were learning English as a second language. If untaught tact and listener responses did not emerge following initial SPOP, MEI, which involved SPOP and tact instruction with novel stimuli, was conducted. The authors found that MEI resulted in the emergence of untaught listener and tact responses with the original instructional stimuli, but the tact relations were not always at criterion levels for all of the participants. These results suggest that explicit reinforcement for an overt selection response is not always necessary for the establishment of listener and tact relations.

The purpose of the present study was to extend previous research on the SPOP by evaluating its effectiveness and efficiency in promoting untaught tact and listener responses. We also used MEI in the instances where participants did not display criterion performance on untaught tact and listener probes. Unlike Rosales et al. (2012), however, in this study, MEI only consisted of SPOP instruction with novel stimuli; we eliminated tact instruction to further isolate any facilitative effects of the SPOP instruction alone. We also examined participants’ echoic behavior throughout specific phases of the study to explore any facilitative role that echoing the experimenter’s names for stimuli may have had on emergent untaught tact and listener relations, a premise consistent with Horne and Lowe (1996). Finally, the participants were children with autism and severe language delays, allowing for the exploration of the potential curricular benefits of the SPOP with this population.

Methods

Participants

Three 7-year-old children diagnosed with autism and severe language delays participated in the study. All three participants attended a communication disorders program within a special education cooperative, and were referred by their teacher for one-to-one language instruction. The participants all displayed tact, mand, and listener skills consistent with those specified in level 1 (developmental level of 1–48 months) of the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP) (Sundberg 2008). Jackson fell in the 22-month developmental range on the Battelle Developmental Inventory, where he was shown to have 45 % and 23 % delays, respectively, in communication and cognition. Scores for the Preschool Language Scale 4th Edition (PLS-4) showed Jackson to be at the age equivalent of 3 years and 4 months for auditory comprehension, and 2 years and 7 months for expressive communication. Jackson echoed 2–3 word phrases. He tacted a few common objects found around the classroom, but his tact repertoire was limited to objects that were directly taught using discrete trials. Jackson correctly selected an item when given the name if the object had been mastered previously through discrete trials.

Jenna was shown to have a 55 and 62 % delay in receptive and expressive communication, respectively, on the Battelle Developmental Inventory. Jenna echoed 2–3 word phrases. She tacted a few food items and common objects found around the classroom, but her repertoire was limited to objects that were directly taught using discrete trials. Jenna correctly selected items when given the name if the object had been mastered previously through discrete trials.

Sophia had been scored in the 5- and 6-month range in receptive and expressive communication, respectively, on the Battelle Developmental Inventory. Her age equivalence on the PLS-4 was reported to be 2 years and 6 months for auditory comprehension and 2 years for expressive comprehension. Sophia echoed 1–2 word phrases. She reliably tacted a few preferred items, but her tacting repertoire was limited to items that were directly taught using discrete trials. Sophia correctly selected the correct item when given the name if the object had been mastered previously through discrete trials.

Setting and Stimulus Materials

Prior to beginning each session, participants were allowed to choose a small toy or sticker from a prize bag, or pick from an assortment of activities, including computer games, iPad time, or watching a movie. Participants exchanged tokens earned over the course of the session for items from a prize bag or 4 min with a selected activity. All sessions were conducted in a partitioned-off area of the participants’ classroom, containing a small table and two chairs. As described in Table 1, three stimulus sets, each containing three 5.1 cm by 6.4 cm. picture cards, were used as instructional stimuli. The target words were one to three syllables in length, similar to those used by Rosales et al. (2012). Three cards were designated as the original instructional stimuli, while the remaining six were designated for MEI. The experimenter used a timer to keep track of stimulus-stimulus intervals during SPOP instructional sessions as well as the schedule of token deliveries.

Table 1.

Stimulus sets for each participant

| Participants | Original set | MEI set 1 | MEI set 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jackson | Ladle | Tambourine | Clarinet |

| Vase | Kiwi | Valve | |

| Bush | Parachute | Pastry | |

| Jenna | Rice | Taxi | Pepper |

| Paint | Kiwi | Fountain | |

| Gum | Ax | Globe | |

| Sophia | Cucumber | Washer | Pliers |

| Colt | Freckles | Wreath | |

| Canoe | Ground | Plantain |

Response Measurement

The two dependent variables were the percentage of correct responses on pretest and posttest tact and listener probes. A correct tact response was recorded if the participant emitted the correct name of a stimulus after the picture card was presented along with the instruction, “What is it?” An incorrect response was recorded if the participant failed to respond within 5 s of the presentation of the instruction, or the participant emitted an incorrect name. A correct listener response was recorded if the participant selected the correct item from an array of three when presented with an instruction such as “Give me the _____” or “Where the _____ is?” An incorrect response was recorded if the participant did not respond within 5 s or the participant selected an incorrect stimulus from the array. We also collected data on the percentage of trials on which participants emitted echoic responses during pretests, posttests, SPOP, and MEI sessions. An echoic response was defined as the participant’s vocal repetition of the experimenter’s dictation of the name of the target visual stimulus (e.g., the experimenter asks, “Where is the ball?” and the participant selects a picture while saying “ball”).

Interobserver agreement was calculated for 35 % of sessions within each condition for all three participants. Secondary observers collected reliability data for each of the participants. A trial- by- trial method was used to calculate reliability in each phase by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of agreements and disagreements and multiplying the result by 100 to obtain a percentage. The mean interobserver agreement for Jackson’s sessions was 100 %, 98.5 % for Jenna’s sessions (range 93.3 to 100 %), and 99.9 % for Sophia’s sessions (range 99.7 to 100 %).

We also collected treatment integrity data for 35 % of all sessions. Treatment integrity was evaluated using specific checklists that were designed by the authors for each phase of the experiment. The purpose of evaluating treatment integrity was to ensure that the experimenter was performing the steps for each phase of the experiment correctly (e.g., delivering a token on a VI 30-s schedule and presenting stimuli in random order). Treatment integrity was calculated by dividing the number of steps that the experimenter performed correctly by the total number of steps and multiplying by 100 to obtain a percentage. The mean treatment integrity for Jackson’s sessions was 99.9 % (range 99.6 to 100 %), 99.5 % for Jenna’s sessions (range 97.3 to 100 %), and 99.9 % for Sophia’s sessions (range 99.8 to 100 %).

Experimental Design

We employed a concurrent multiple probe design across participants (Horner and Baer 1978). Tact probes were presented prior to listener probes. SPOP instructional sessions were implemented following pretest probes, after which tact and listener posttest probes were presented. If a participant did not perform with at least 8/9 (89 %) accuracy per 9-trial block on tact and listener posttest probes, MEI, consisting of SPOP sessions with novel instructional stimuli, was implemented. Following MEI, tact and listener posttest probes were repeated using the original instructional stimuli. If the targeted skills with the original instructional stimuli did not emerge, we conducted remedial SPOP instruction with the original instructional stimuli, followed by tact and listener posttest probes. If a participant did not demonstrate criterion performance on posttest probes, we conducted a second round of remedial SPOP instruction with the original set of stimuli.

Procedure

Pretests

Two 9-trial blocks of tact and listener probes were conducted during each pretest session. The experimenter explained the following: “I am going to ask you some questions, but I won’t be able to tell you if you are right or wrong. You can earn tokens for sitting with your feet on the floor, looking at the pictures, and listening. Are you ready?” After the participant indicated that he or she was ready by having feet on the floor and looking at the experimenter, one 9-trial block of tact probes was conducted. Tact pretest probes consisted of the experimenter presenting the stimuli one at a time directly in front of the participant along with the instruction “What is it?” Participants were given 5 s to respond before the stimulus was removed from view. A 9-trial block of listener probes was presented following tact probes. During listener trials, a linear array of three stimuli was presented on the table in front of the participant. The experimenter gave the instruction, “Point to the _____” or “Where is the _____.” Participants were given 5 s to respond before the stimuli were cleared from the table. Each stimulus was presented three times in random order during tact and listener 9-trial blocks (i.e., 18 trials per session). No feedback, prompting, or error correction was provided during listener or tact probes. Tokens were delivered on a variable interval schedule of 30 s (VI 30) for appropriate attending and sitting. The participant was able to access the prize or activity that he or she had chosen prior to the session in exchange for ten tokens.

SPOP Instruction

Prior to each session of SPOP instruction, participants were given the following instructions: “I will be showing you some pictures. Look at the pictures and listen. You can earn tokens for sitting with your feet on the floor, looking at the pictures, and listening. Are you ready to start?” Before presenting each trial, the experimenter obtained the participant’s attention and ensured that his or her eyes were directed toward the stimulus. The experimenter presented each stimulus while dictating the name of the item (e.g., stating “pencil” while presenting a picture of a pencil). Each trial consisted of an approximately 2-s presentation of the stimulus along with its dictated name. Five 9 trial-blocks were conducted per instructional session, for a total of 45 trials total throughout one instructional session. Each of the three stimuli in the set was presented three times per 9-trial block. Thus, there were 15 instructional trials per stimulus within a single session. The order of presentation of stimuli within each 9-trial block was randomized. An ITI of 2–3 s separated each trial. Appropriate sitting and attending was reinforced using the same procedure as during test sessions. If the participant was not attending, the experimenter said “look at the picture” while pointing to the stimulus and moving the stimulus into the participant’s line of vision. If the participant was not sitting appropriately, the experimenter stated: “Sit up with your feet on the floor.” One SPOP session was conducted with the original set of stimuli for each participant to evaluate if the listener and tact responses would emerge with this procedure alone.

Posttests

Posttest probe sessions were conducted following each SPOP session and were identical to pretests. For the original set of stimuli multiple posttest sessions were conducted following one SPOP session. Posttests were conducted until stable responding was observed across posttest sessions before moving on to the MEI phase. If the participant correctly responded to 8/9 listener probes and correctly responded to 8/9 tact probes across three consecutive sessions for the original set of stimuli, the participant met mastery criteria and the study was considered complete for that participant. If participants did not meet the mastery criteria, and an upward trend for both listener and tact responses was absent following 3–4 sessions, MEI was conducted first with the MEI set 1 stimuli and then with the MEI set 2 stimuli.

MEI

MEI consisted of the implementation of SPOP with two novel sets of stimuli consisting of three stimuli each. One set of stimuli was introduced at a time. Probe sessions were conducted following each SPOP session until mastery criteria were met. Participants were required to demonstrate 8/9 correct responses (89 % correct) per 9-trial block for tact and listener probes across three consecutive sessions for both sets of stimuli for MEI to be completed. Therefore, unlike the original SPOP training, multiple SPOP MEI sessions were conducted with each respective set of stimuli. Otherwise, sessions were identical to the previous SPOP sessions.

Remedial SPOP Instruction

Remedial SPOP instruction was conducted with the original set of stimuli and in the same manner as the original SPOP instruction sessions. This phase was implemented if the participant did not show the emergence of tact and listener responses with the original instructional stimuli following the completion of MEI with both MEI stimulus sets.

Results

Emergent Tacts

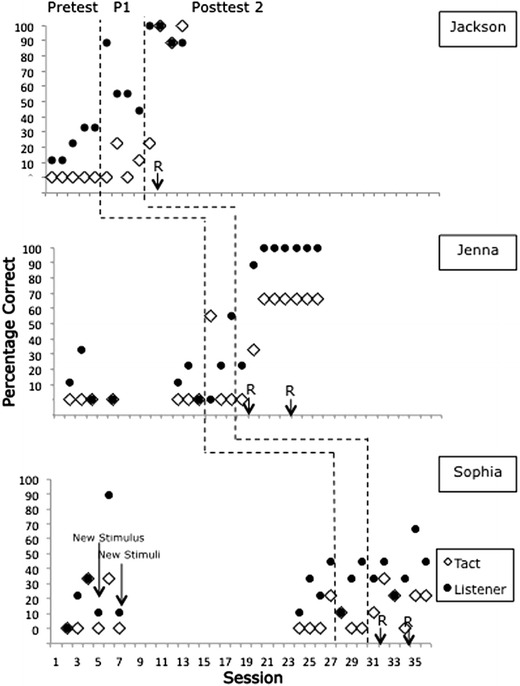

The percentage of correct tact responses on pre- and posttest probes for each participant is shown in Fig. 1. Jackson performed with 0 % accuracy during pretest probes, and scores increased within a range of 0 to 22 % correct during posttests following initial SPOP instruction. Following two rounds of MEI, Jackson displayed only 22 % correct responding on tact test probes during the posttest before remedial instruction. Following remedial SPOP instruction with the original stimuli (depicted by an R on the graph), Jackson’s tact responses increased to 96.3 % correct on average over the next three probe sessions (range 89 to 100 %).

Fig. 1.

The percentage of correct tact and listener responses with the original set of stimuli for Jackson, Jenna, and Sophia. Remedial instruction is depicted by the “R” along the x-axis. Posttest 1 with the original set of stimuli is depicted by the “P1” condition label

Jenna performed with 0 % accuracy during pretest probes, and her scores increased to 56 % in the initial posttest probe following initial SPOP instruction. However, her accuracy on next two tact posttest probes decreased to 0 %. Following MEI, her tact responses remained at 0 % correct. After a remedial SPOP session was implemented with the original stimuli, Jenna’s tact responding increased to 33 % correct for the initial test probe and 66 % correct for the remaining test probes. Following another round of remedial SPOP between posttests five and six, tact accuracy remained consistent at 66 % correct.

Sophia performed with 0 % accuracy during pretests; however, her accuracy increased to 33 % correct during the third pretest session. A new, unknown stimulus was identified to replace the stimulus that Sophia tacted correctly. During the fifth session, Sophia’s correct responding increased to 33 %. Following the fifth session, three new stimuli were identified and introduced. Sophia’s pretest scores with the new stimulus set remained at 0 % correct for the remainder of the pretest probes. After the initial SPOP instruction, her posttest tact scores increased to 22 %; however, her scores deteriorated during the remaining two sessions with a mean score of 5.5 % correct (range 0 to 11 %). Following MEI, her tact responses remained at 0 % correct throughout her posttest 2 sessions. After a remedial SPOP session was implemented with the original stimuli, Sophia’s mean tact score was 22.2 % correct (range 11 to 33 %). Following a second remedial instruction, her scores continued to vary with a mean of 15 % correct (range of 0 to 22 %).

Emergent Listener Responses

In addition to the percentage of correct tact responses, Fig. 1 shows the percentage of correct listener responses for each participant. During pretests, Jackson’s mean accuracy for listener responding was 22.2 % correct (range 0 to 33 %). Following initial instruction, Jackson’s listener responding scores immediately increased to 89 % correct, but deteriorated to a mean of 51 % correct (range 44 to 55 %) for the following three posttest sessions. After MEI was completed, Jackson’s listener responses for the original set of stimuli increased to 100 % correct. Remedial instruction was implemented to evaluate whether the tact responses would emerge. Following the remedial instruction, Jackson’s listener responding scores continued to meet criterion with a mean of 92 % correct (range 89 to 100 %).

During pretests, Jenna’s mean listener responding score was 13 % correct (range 0 to 33 %). After initial SPOP instruction, a slight increase in responding was observed, with a mean score of 37 % correct (range 0 to 56 %). In the first posttest session following MEI, Jenna responded correctly on 22 % of the listener trials. After a remedial SPOP instructional session was implemented, Jenna’s listener responding increased to criterion with a mean of 98 % correct (range 89 to 100 %).

Sophia’s listener responses during the first four pretest sessions varied, with a mean of 16.5 % correct (range 0 to 33 %). However, in the fifth session her accuracy increased to 89 % correct. Following the third and fifth session, new stimuli were identified due to increases in her percentage of correct responses (see Table 1). Listener responses with stimuli from the original set remained at or below chance levels for the remainder of the pretest sessions with a mean of 22.2 % correct (range 11 to 33 %). After the initial SPOP instruction, accuracy on listener trials varied with a mean of 29.3 % correct (range 11 to 44 %). Sophia’s accuracy on listener test probes increased to 55 % correct in her first posttest session after MEI. After remedial SPOP was implemented, Sophia’s listener scores ranged from 22 to 44 % accuracy, with a mean of 33 % correct. After a second remedial instructional session was implemented, her scores remained variable with a mean of 48 % (range 33 to 67 %).

SPOP Instruction

Table 2 shows the number of SPOP instructional blocks required for participants to demonstrate criterion performance on posttests with the original and two MEI stimulus sets. Only Jackson reached criterion on emergent listener and tact skills during posttests with the original stimuli. The table also shows the number of instructional trial blocks needed to reach mastery criteria for each MEI stimulus set across the three participants. The participants required a number of instructional sets before displaying criterion performance (if at all). All three participants required more exposures to the auditory stimulus and visual stimulus pairings for the second MEI set.

Table 2.

Number of trial blocks necessary to demonstrate criterion performance on posttests

| Participants | Original set | MEI set 1 | MEI set 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jackson | 10 | 15 | 40 |

| Jenna | – | 30 | 85 |

| Sophia | – | 15 | 70 |

Echoic Responding

Table 3 shows the mean percentage of trials during which each participant engaged in echoic responding when the experimenter dictated the names of the stimuli during listener probes and SPOP sessions. The table shows that for all three participants, the highest mean numbers of echoics occurred for SPOP instructional sessions with the three stimulus sets, compared to the listener pretest probes. Both Jenna and Sophia engaged in more echoic responding during listener posttest probes than Jackson. Jackson, the only participant who displayed criterion performance on listener and tact probes with the original set of stimuli, also had the lowest mean percentage of echoic responses for the listener posttests.

Table 3.

Mean percentage of trials on which participants echoed the experimenter’s dictation of stimulus names

| Jackson | Jenna | Sophia | Total mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original set | Listener pretest | 25.9 % | 63.5 % | 83.3% | 57.6 % |

| SPOP | 96.7 % | 96.3 % | 97 % | 96.7 % | |

| Listener posttest | 34.7 % | 81.8 % | 97. 8 % | 71.4 % | |

| MEI set 1 | Listener pretest | 18.5 % | 33.3 % | 100 % | 50.6 % |

| SPOP | 94.1 % | 91.1 % | 94.1 % | 93.1 % | |

| Listener posttest | 66.7 % | 73.6 % | 93.7 % | 78 % | |

| MEI set 2 | Listener pretest | 66.7 % | 22.2 % | 0 % | 29.6 % |

| SPOP | 92.8 % | 98.3 % | 92.5 % | 94.5 % | |

| Listener posttest | 44.4 % | 93 % | 79.1 % | 72.3 % | |

Discussion

The goal of the current investigation was to determine if SPOP instruction and MEI consisting of SPOP instruction with additional stimuli were effective and efficient in establishing emergent listener and tact relations in children with autism and severe language delays. We found that multiple exposures to SPOP instructional sessions resulted in increases in both listener and tact responding for all participants. All three participants demonstrated criterion performance for both the listener and tact responses with two MEI sets of stimuli, and one participant demonstrated criterion performance for both the listener and tact responses with the original set of stimuli. These results are consistent with those of Rosales et al. (2012), who reported the use of this procedure with typically developing preschoolers learning English vocabulary words, and lend further support for the notion that the simple pairings of auditory and visual stimuli may be effective for the development of listener and tact responses (Leader et al. 2000; Leader and Barnes-Holmes 2001a; Leader and Barnes-Holmes 2001b).

Horne and Lowe (1996) suggest that a repertoire of naming develops following a history of reinforcement for listener, echoic, and speaker behaviors. MEI seems to facilitate the establishment of joint stimulus control of visual stimuli, so that both listener and speaker responses associated with naming may occur (Fiorile and Greer 2007; Greer et al. 2005). For example, consider the case of a child whose attending and orienting to a puppy when she hears the spoken word “puppy” is reinforced, as is saying “puppy” in the presence of a puppy. After joint stimulus control of this sort is established with multiple stimuli, new untaught responses may emerge without being directly taught. The current investigation offers additional support for the use of MEI with children with autism. Following two sets of MEI and remedial SPOP instruction, some listener and tact responses emerged for both Jackson and Jenna (i.e., at least two out of three tacts) with the original stimulus set. The effects for Sophia were relatively less pronounced, but her accuracy improved somewhat following MEI and remedial SPOP instruction.

The results for participants’ echoic responding during specific portions of the experiment were somewhat surprising, because the results did not necessarily support a facilitative role for echoic behavior. The three participants engaged in echoic behavior most substantially during SPOP instructional sessions, but Jackson, the only participant to have demonstrated criterion performance on emergent listener and tact probes, displayed echoic responding on the lowest proportion of trials. According to the naming account, as the bidirectional name relation develops, an individual may echo the utterances of caregivers, such that his or her own echoic behavior may control subsequent listener responding (Horne and Lowe 1996; Greer and Keohane 2005; Hawkins et al. 2009). We might, therefore, have expected Jackson to have shown the most, not least, echoic behavior throughout the experiment. Horne and Lowe (1996) do acknowledge that such echoic behavior can recede to the covert level. Indeed, Skinner’s (1957) analysis of verbal behavior suggests the same. A possibility that was not empirically evaluated in the present study is that Jackson engaged in echoic responding covertly, and these responses may have facilitated tact and listener responding. Future research could explore the use of indirect measures to evaluate covert verbal behavior (Aguirre and Rehfeldt in press).

There are several limitations to the current study that warrant mention. Although SPOP appeared to be effective in establishing untaught listener and tact relations, it may not have been efficient. Numerous MEI trial blocks were necessary before criterion levels of performance were observed. However, it is not clear whether the same result would have occurred had we simply conducted more SPOP sessions with the original instructional stimuli rather than the MEI stimuli. We note that Rosales et al. (2012) implemented remedial SPOP instruction (i.e., additional sessions with the original stimuli) following initial training, but still found it necessary to conduct MEI. Thus, the evidence from these two studies suggests that MEI facilitates the emergence of untrained responses, although it is not known whether it is necessary. However, unlike in Rosales et al. (2012), tact instruction was not a component of MEI in the current study. On a related note, Hawkins et al. (2009) explicitly taught either the listener or tact response for multiple stimuli and then assessed whether the untaught response emerged. They found that naming was not established until an echoic component was added to the protocol. Although Hawkins et al. (2009) did not use the SPOP, the results of this study suggest the importance of establishing echoic responses to enable the emergence of listener or tact responses. Along those lines, it is possible that directly teaching tacts or echoics during MEI in the current study would have led to more efficient training. Such instruction may well have produced increases in tact and listener responding with the original instructional stimuli.

Our results are also consistent with those of Rosales et al. (2012) in that participants performed with higher accuracy on listener test probes than tact test probes. Both studies, however, showed increases in tacts with original stimuli following MEI. Similar to the Rosales et al. study, we found that listener responses emerged to a greater extent than tact responses after SPOP and MEI sessions. However, both studies showed increases in tact responses with the original stimulus set after SPOP and MEI sessions (although in the current study, the effects for Sophia were small). SPOP may only be effective with participants who have already acquired specific prerequisite listener responses, such as discriminating between the speech sounds of others and perceptually orienting toward environmental stimuli (Horne and Lowe 1996). Further investigation is needed to examine what prerequisite skills are necessary for the SPOP to be an effective instructional procedure. The VB-MAPP Barriers Assessment (Sundberg 2008) may be one avenue for identifying the prerequisite skills for effective SPOP instruction. Sophia may have simply needed additional instruction on such potential prerequisite skills.

It is also not clear to what extent a well-developed echoic repertoire may increase the instructional effectiveness of SPOP for individuals. Horne and Lowe (1996) suggest that an echoic repertoire is an important component of the name relation. Jackson and Jenna echoed 2–3 word phrases prior to the study, but Sophia echoed 1–2 word phrases. Sophia’s echoic repertoire may not have been sufficiently sophisticated for the development of the name relation. Unfortunately, information on echoics, listener responses, and tacts mastered to date was not available to the authors. This information might have provided additional insight regarding the discrepant performances observed across the three participants. Prior research has reported increases in tact responses after echoic instruction in combination with tact or mand instruction in children with autism (Barbera and Kubina 2005; Kodak and Clements 2009). More studies are needed to examine the role that explicit echoic instruction may play in the emergence of naming.

Another limitation experienced during this study was challenging behavior by Sophia during the posttest probes. This included lying on the floor, looking away from the stimuli, and refusing to respond. It seems likely that this problem behavior may have led to increased variability and lower posttest scores than otherwise might have been the case. SPOP, particularly when conducted across multiple stimulus sets, may potentially result in extinction of participants’ responses, given the lack of feedback for an overt response. Examples observed with Sophia in this study that may suggest a potential extinction burst included selecting multiple picture cards during a single listener trial as well as providing incorrect tact responses in the form of repeating the same response for each trial. All of the participants required a greater number of SPOP instructional blocks to attain mastery criterion on emergent tact and listener posttests for their second set of MEI stimuli, possibly for this reason. Instructional conditions such as these may produce undesirable collateral responses that may interfere with the participants’ responding. Although tokens and praise were delivered independent of participants’ performance on test trials, the sheer number of test trials presented without feedback may help explain why performance was not at criterion levels for all of the participants. To reduce this risk, it might be beneficial to intersperse maintenance tasks during test probes, and reinforce correct responses to these tasks on a dense schedule. Also, it is possible that the experimenters may have adventitiously reinforced correct listener, tact, and echoic responding when delivering tokens for attending and sitting behavior. In future studies, researchers might be able to determine whether accuracy improves immediately following the delivery of such reinforcers. Reducing the density of reinforcement for good attending, sitting, and working over the course of the experiment may reduce the chances of adventitiously reinforcing correct responses.

Future studies should focus efforts on establishing the efficiency of SPOP instruction, particularly in comparison to direct instruction of tact and listener skills. Examining the long-term maintenance of such skills also seems in order. Our results contribute to the meager body of literature illustrating the educational benefits of SPOP instruction, as this is the first study reported to evaluate the use of the SPOP with young children with autism. The need for effective and efficient teaching methods is imperative for this population. Even children with severe language delays may acquire these skills incidentally by observing others naming and interacting with environmental stimuli. The SPOP required numerous pairings of the auditory and visual stimuli during MEI; however, the response effort required of participants was minimal and the procedure was easy for the experimenter to implement. These findings have implications for small group instructions in both typical and special education classrooms, because they may shed light on how children are able to learn from the relatively informal and less structured experiences (compared with behavioral instruction) that frequently occur in these contexts. In addition, the SPOP provides a laboratory parallel of certain types of language interactions as they occur between young children and their caregivers or peers, making it a relevant procedure for investigations of rudimentary language acquisition. Future research might also investigate if participants learn more effectively naturalistically or incidentally after experience with SPOP instruction.

Acknowledgments

Author Note

This project constituted a master’s thesis completed by the first author under supervision of the second author in the Behavior Analysis and Therapy program at Southern Illinois University.

References

- Aguirre, A. A., & Rehfeldt, R.A. (in press). An evaluation of the effects of visual imagining and instruction on the spelling performance of adolescents with learning disabilities. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barbera ML, Kubina RM., Jr Using transfer procedures to teach tacts to a child with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:155–161. doi: 10.1007/BF03393017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorile CA, Greer RD. The induction of naming in children with no prior tact responses as a function of multiple exemplar histories of instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2007;23:71–87. doi: 10.1007/BF03393048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Keohane DD. The evolution of verbal development in young children. Behavior Development Bulletin. 2005;1:31–48. doi: 10.1037/h0100559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Stolfi L, Chavez-Brown M, Rivera-Valdez C. The emergence of the listener to speaker component of Naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:123–134. doi: 10.1007/BF03393014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Stolfi L, Chavez-Brown M, Pistoljevic N. Emergence of naming in preschoolers: a comparison of multiple and single exemplar instruction. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2007;8(2):109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins E, Kingsdorf S, Charnock J, Szabo M, Gautreaux G. Effects of multiple exemplar instruction on naming. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2009;10:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behaviors. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:185–241. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF, Randle VRL. Naming and categorization in young children: II. Listener behavior training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;81:267–288. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.81-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RD, Baer DM. Multiple-probe technique: a variation of the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:189–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Clements A. Acquisition of mands and tacts with concurrent echoic training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42(4):839–843. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Barnes-Holmes D. Establishing fraction-decimal equivalence using a respondent-type training procedure. The Psychological Record. 2001;51:151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Barnes-Holmes D. Matching to sample and respondent-type training as methods for producing equivalence relations: isolating the critical variable. The Psychological Record. 2001;51:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets PM. Establishing equivalence relations using a respondent-type training procedure III. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe CF, Horne PJ, Harris FDA, Randle VRL. Naming and the categorization in young children: vocal tact training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:527–549. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, Rehfeldt R, Huffman N. Examining the utility of the stimulus pairing observation procedure with preschool children learning a second language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:173–177. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth S, Barnes-Holmes D, Forsyth JP. A derived transfer of simple discrimination and self-reported arousal functions in spider fearful and non-spider-fearful participants. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85:223–246. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.02-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML. Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program. Concord, CA: AVB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]