Abstract

The present study replicated and extended the Pelaez et al. (Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 44:33–40, 2011) study, which examined the reinforcing effects of mothers’ contingent imitation of their infants’ vocalizations. Three infants aged 7–12 months who could vocalize sounds but not words participated with two caregivers for each infant (i.e., triads). During the intervention phase, the caregivers were asked to immediately imitate all vocalizations emitted by the child for a 3-min period. During the yoked control phase, the caregivers listened to an audio recording from the preceding condition and provided vocalizations non-contingently on the infants’ responses. The procedures yielded different results across participants; one infant emitted a higher frequency of vocalizations during the contingent imitation phases over the control phases, and the other two infants showed higher rates of responding during the control phases. However, all infants emitted more imitative return vocalizations during contingent reinforcement conditions compared with the yoked control condition.

Keywords: Infant vocalizations, Language acquisition, Maternal imitation, Echoics, Vocal conditioning, Differential reinforcement of other behavior

A significant amount of research has been conducted on the relation between the development of preverbal skills in infants and later language development and academic achievement (see Pelaez et al. 2011). For example, Hart and Risley (1995) examined the differences in vocabulary development over time among children of varying socioeconomic backgrounds. At age 3, larger vocal repertoires in children were correlated with higher socioeconomic status of the family. These findings were thought to be a function of differences in the frequency and richness of words addressed to the children, as well as parents providing additional prompting for the children to participate in reciprocal interactions. Positive correlations were found between children’s early language repertoire and academic success at 9 and 10 years of age. Given the results of Hart and Risley’s (1995) study and the implications for influencing later academic skills and success, consideration of behavioral mechanisms responsible for larger verbal repertoires of infants is critical. The increase in reciprocal interactions that occurred with parents of higher socioeconomic status suggests the role of imitation as one possible mechanism for the increase in infant vocal verbal behavior.

A behavioral analysis of imitation was proposed in Skinner’s (1957) analysis of verbal behavior. The echoic was defined as behavior under the functional control of a verbal stimulus in which both the stimulus and response share point-to-point correspondence. The foundations for echoic behavior begin when infants make sounds and caregivers then reinforce the imitative vocal behavior successively through physical contact, smiling, and making sounds in response.

Research on the effects of contingent caregiver responses to infant behavior has been a prevalent topic across psychological literature. A review by Dunst et al. (2010) identified 22 studies, conducted between 1959 and 2008, which examined the effects of adult verbal and vocal contingent responses with respect to changes in infant vocalizations. In relation to promoting larger vocal verbal repertoires, researchers have found maternal responsiveness to be a more reliable indicator of the onset of infant’s future language milestones than any specific infant behavior (Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2001). Prior research has also found that infants around 10 months of age who emitted return vocalizations following caregiver vocalizations had greater vocal verbal repertoires during late infancy and early toddlerhood (Masur and Olson 2008) indicating that infant responsiveness is also a predictor of language milestones.

A more recent study by Pelaez et al. (2011) investigated the effects of contingent maternal imitation of infant vocalizations in order to determine whether the contingent response functioned as a reinforcer for longer-term behavior change, as opposed to simply having a temporary evocative effect on the infant’s behavior. A BAB reversal design was used in which the caregiver provided either contingent imitation or non-contingent vocalization following their infant’s vocalizations. This design included a control condition in which mothers provided non-contingent social attention using differential reinforcement of other (DRO) behavior (a potential buffer against emotional responding). Within only a few sessions, the frequency of vocalizations decreased during the DRO condition and increased in the contingent imitation condition for 10 out of the 11 infants.

The purpose of the current study was to replicate and extend the methodology of Pelaez et al. (2011) to infants and multiple caregivers, to reveal whether findings would generalize to caregivers other than mothers. Because little research has analyzed the effects of infant–caregiver interactions with caregivers other than a child’s mother, this extension sought to make conclusions regarding any differences in infant behavior that occurred with mothers versus other caregivers, as well as differences occurring between caregivers who spent similar versus different amounts of time interacting with their infant. Much as Hart and Risley (1995) found that the quality and quantity of vocalizations emitted across families resulted in differing vocal repertoires, it is possible that the quality and quantity of words spoken between specific caregivers may evoke different vocal repertoires in the infant.

Other extensions to the Pelaez et al. (2011) study involved conducting additional conditions across multiple days, in an attempt to achieve more reliable results. In order to better assess the reinforcing effect of contingent imitation, within-session data as opposed to aggregate data are presented. The current study also examined infant participants outside of the 3- to 8-month range used in the original study to evaluate whether slightly older children, especially one with a speech delay, would show the same results; the age range extension was also necessary to study the occurrence of return vocalizations emitted by infants during each condition.

Method

Participants

Three participant triads were recruited, each made up of an infant, mother, and one other caregiver. Infant participants were three Caucasian males with a mean age of 9.5 months, none of whom had been diagnosed with any disability or serious medical condition, although the mother of participant 2, Liam, reported a slight speech delay. All infant participants were observed to make simple vocalizations and/or babbling sounds but no words. Participants were recruited by sending a letter to friends, family, and acquaintances who in turn contacted other acquaintances with children who fit the participation criteria.

Participant 1, Max, was a 7-month-old male who lived with his mother and father. Participant 2, Liam, was a 12-month-old male who lived with his mother and his grandmother who was temporarily residing with the family. Participant 3, George, was a 9.5-month-old male who lived with his mother and father. For all participant triads, sessions were scheduled to accommodate the child’s typical daily eating and sleeping patterns.

Materials and Setting

All sessions took place in the homes of the participants in a room where noises and distractions were minimized. One to two video cameras were set up a few feet away to record the occurrence of infant and caregiver vocalizations. A digital recorder, tie-clip microphone, and pair of over-the-ear headphones were also used so that the caregivers’ vocalizations could be digitally recorded and played back later for the caregiver to imitate during the subsequent yoked control condition. Questionnaires were created and distributed to caregivers prior to the start of the first experimental session that asked pertinent questions regarding their relationship with the child, including the nature of the relationship and amount of interaction time that occurred per day and per week.

Experimental Design

Manipulation of the independent variable (caregiver vocalization) and its effects on the dependent variable (rate of infant vocalizations) were assessed using a BABA-BA, BABA, or BA-BA reversal for both caregivers. In this notation, “B” indicates a contingent imitation session, “A” indicates a control session, and a dash indicates a separation of days. In all participant triads, the mother completed the first set of conditions on the first day and the other caregiver completed the next session. Each contingent imitation condition and control condition lasted 3 min with a short break between.

Dependent Variables, Response Measurement, and Interobserver Agreement

The primary dependent variable was infant vocalization, defined as one or more vocal utterances consisting of vowel sounds or consonant-vowel sound combinations that occurred without a break of more than 1 s. Thus, a vocalization such as “bababa” was counted as one vocalization if no more than 1 s separated each phoneme or syllable. Non-examples of vocalization included coughing, crying, belching, hiccupping, sneezing, whining, or any other vocalizations that appeared to be a precursor to crying based on corresponding facial expressions (based on Pelaez et al 2011).

The experimenter also tracked the number of return vocalizations the infant made in response to the caregiver’s imitative vocalization. A return vocalization was defined as an exact or partial imitation of a caregiver’s contingent vocalization made within 2 s of the caregiver’s vocalization. Exact and partial vocalizations were coded separately; an exact return vocalization had the same consonant and vowel sounds as the caregiver sound and the same number of phonemes (e.g., caregiver says “ba,” then infant says “ba”). A partial return vocalization had at least one of the same characteristics of the caregiver’s vocalization, such as the same consonant or vowel sounds or the same number of phonemes, but at least one syllable was different (e.g., caregiver says “ba,” infant says “ma”; or caregiver says “baba,” infant says “ba”).

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated for 28 % of sessions for both the number of infant and caregiver vocalizations that occurred per 15-s interval. Observer agreement values were 100 % for caregiver vocalizations; agreement values for infant vocalizations ranged between 83 and 100 % across sessions, with a mean of 88 %.

Procedures

Procedures for contingent imitation (B condition) and yoked DRO Control (A condition) were replicated from Pelaez et al. (2011). In order to ensure that frequency of caregiver vocalizations could not account for differences in infant vocalizations between sessions, the audiotape was used to yoke the number of vocalizations from the contingent imitation condition to the control condition. A DRO schedule was utilized to prevent reinforcement of infant vocalizations during the control condition while still providing some form of reinforcement for other emitted behavior; prior research has demonstrated this to be an effective control procedure in place of extinction-based control conditions that would likely evoke emotional responding in young children (Poulson 1983; Thompson and Iwata 2005).

Contingent Imitation (B Condition)

Prior to the start of each contingent imitation condition, the caregiver was instructed to maintain eye contact with the infant, smile, and use a normal speaking voice to deliver the contingent imitations regardless of the magnitude of the infant responses. The infant was placed in a high chair or baby seat an arm’s length away from the caregiver who sat directly across from the child. During the sessions, the experimenter monitored the participants from several feet away to minimize observer reactivity.

The caregivers’ vocalizations were audio-recorded during this condition for the purpose of playback during the subsequent yoked DRO control conditions. When not emitting a vocalization, the caregiver was instructed to maintain eye contact, remain silent until the occurrence of the next infant vocalization, and refrain from physical contact with the infant.

Yoked DRO Control (A Condition)

At the start of the control condition, the 3-min recording from the previous intervention session was played through headphones in the caregiver’s ears. The caregiver was instructed to imitate the vocalization immediately upon hearing it. However, to ensure that caregiver vocalizations did not occur contingent on infant vocalizations, the experimenter watched and listened to the session as it occurred, pausing the tape each time the infant vocalized. The experimenter started the tape again 4 s after the end of the infant’s vocalization.

During the first set of sessions with Max, the control condition involved a simultaneous start of the session and the entire recording from the previous contingent imitation session. However, since vocalizations did not occur on the recording for close to 1 min, the caregiver did not emit any vocalizations for a long period. The infant then engaged in distressed and attention-seeking behavior that interfered with the session. The procedure was then changed for all remaining conditions and participants such that the tape was cued up to just before the first vocalization during the previous B condition. While there were some minor discrepancies in yoking the frequency of reinforcement between conditions, the number of caregiver vocalizations typically did not vary greatly from contingent to control conditions (with the exception of George, in which there was a differentiation of 18 vocalizations from one contingent imitation condition to control condition; the largest differentiation for Max and Liam was six vocalizations). In cases in which the number of caregiver vocalizations in the contingent and the control condition was not equal, the number of caregiver vocalizations during the contingent condition always exceeded the number of caregiver vocalizations in the subsequent control condition.

Treatment Integrity

Prior to the start of each contingent imitation condition, the experimenter provided training and feedback to the caregiver on how to deliver vocalizations and specific guidelines regarding eye contact, smiling, and physical contact. Delivery of the contingent imitations during intervention phases and non-contingent vocalizations during the control phases was monitored by the experimenter during sessions and by the experimenter and research assistant during video re-play. The experimenter conducted assessments of treatment integrity using a checklist for 100 % of sessions. All participants had high treatment integrity; the mother and father of Max scored an average of 100 and 97 % across sessions, respectively. The mother and grandmother of Liam scored an average of 100 and 97 % across sessions, respectively. The mother and father of George scored an average of 97 and 100 % across sessions, respectively.

Results

Questionnaires given to the caregivers of each participant revealed differences in the amount of hours spent at home. For Max, there was a large difference in the number of hours spent at home with the child between the mother (around 42.5 waking hours per week) and father (between 20 and 24 waking hours a week). Liam’s caregivers appeared to spend about equal amounts of time and participated in similar activities with the child. For George, there was also a large difference in the amount of time spent with the mother and father. George’s mother spent the majority of the day with the child (around 8 waking hours per day), while the father typically spent around 1 h with the child on weekdays, and 4 h a day on weekends; activities with the child were similar between the mother and father.

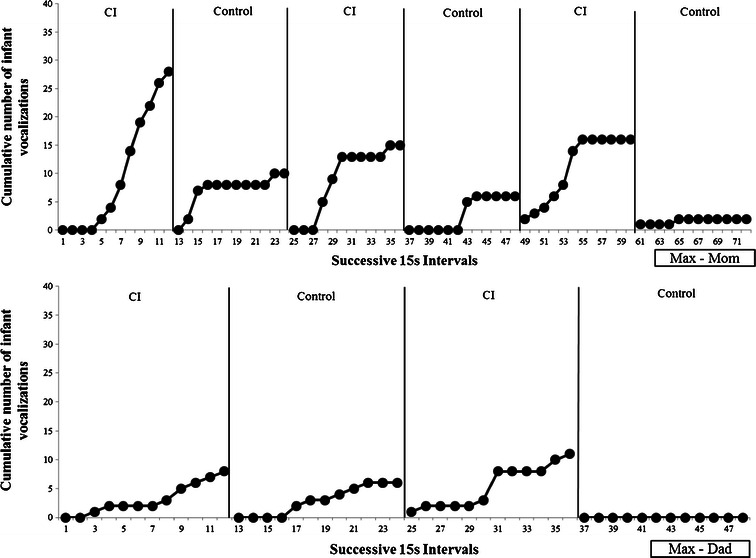

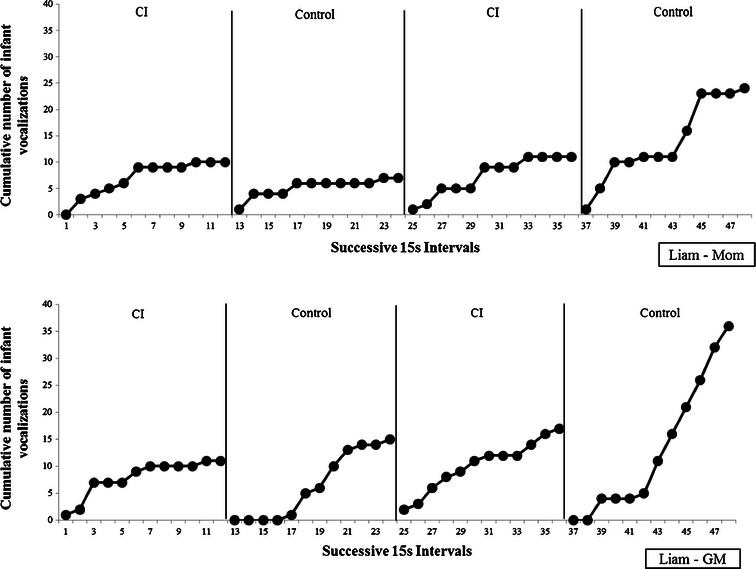

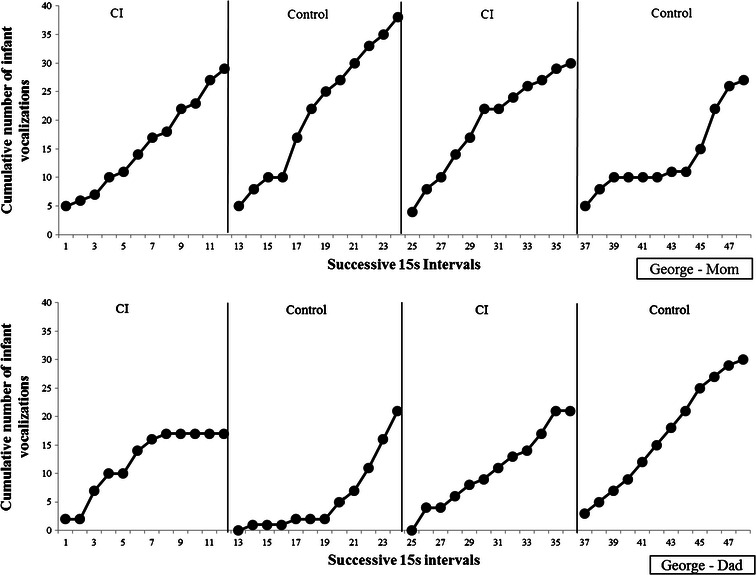

Figures 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 1 representing data for Max, Fig. 2 for Liam, and Fig. 3 for George) show cumulative vocalizations across sessions for all participants. While the Pelaez et al. (2011) study depicted only aggregate data, cumulative data are shown to portray both within- and between-session frequencies. If vocalizations function as a reinforcer, cumulative data should depict increases in infant vocalizations across contingent imitation sessions over time and higher rates of vocalizations should occur across the span of the 3-min session. Max showed a higher rate of vocalizations during sessions with his mother than his father. During sessions with his mother, Max emitted higher rates of vocalizations during contingent imitation sessions compared to control sessions. During sessions with his father, Max emitted more vocalizations during contingent sessions as well. In sessions with his mother, Liam had overall higher rates of responding and an increase across control sessions. During sessions with Liam’s grandmother, vocalizations increased over time. George emitted a high rate of vocalizations during all sessions with both his mother and father, though the within-session patterns of responding differed. Sessions with George’s mother yielded high rates of responding across all conditions. Patterns of vocal responding with George’s father showed similar cumulative values during the initial BAB sessions and the highest rate during the final control condition.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative number of within-session infant vocalizations across conditions and caregivers for Max. CI denotes contingent imitation sessions

Fig. 2.

Cumulative number of within-session infant vocalizations across conditions and caregivers for Liam

Fig. 3.

Cumulative number of within-session infant vocalizations across conditions and caregivers for George

Figure 4 displays the frequency of exact and partial return vocalizations made by the infant following a caregiver’s imitative response of the infant’s initial vocalization (during the contingent reinforcement conditions) or following a caregiver vocalization (during the control conditions). The return vocalizations occurred at higher overall rates in the contingent reinforcement conditions and with mothers for all participants, indicating some reinforcing imitation function.

Fig. 4.

Frequency of return vocalizations across sessions and caregivers. B denotes contingent imitation conditions; A denotes control conditions

Discussion

Only the first participant, Max, demonstrated a pattern of behavior similar to the aggregate data of the infants in the Pelaez et al. (2011) study. While Max was the only participant with a similar age to those in the Pelaez et al. study, age may not be the most likely explanation for the differentiation in findings between Max and the other two participants who were older. In typical environments, babbling gains strength at around 6 months and becomes more refined and indicative of the child’s language learning environment between 8 and 10 months (Oller and Eilers 1988; Schlinger 1995). Other similar studies (see Dunst et al. 2010 for a review) on maternal contingent responses have used participants between 2 and 12 months of age with findings similar to those of Pelaez et al. demonstrated for children between 9 and 10 months (Goldstein and Schwade 2008).

The high rates of responding shown by Liam and George during control conditions could have occurred as a result of extinction, assuming that caregiver contingent imitation functions as a reinforcer, and that the withholding of the direct contingency is responsible for extinction-induced behavior. During the control conditions, all infant participants emitted some crying and distressed vocalizations. However, Liam and George also displayed response variability during these sessions, perhaps indicative of extinction. Both children engaged in overt, attention-seeking behaviors, such as flailing arms, leaning forward, banging on the high chair, and other vocal behavior, such as making blubbering sounds and increasing the volume and tone of non-distressed vocalizations (e.g., an emphatic “ba!”). While no formal baseline measures were collected, all caregivers stated to the experimenter that prior to the start of the study, they occasionally imitated the child’s vocalizations; this reinforcement history may have contributed to emotional responding and extinction-induced behavior since it likely differed greatly from typical interactions between the caregiver and child. Thus, the fact that extinction-induced behavior did not result in an increase in vocalizations during control conditions for Max, but instead increased other adjunctive behaviors, may have been due to a shorter reinforcement history with respect to vocal exchanges (which could be related to the age difference, though this is not necessarily true) or due to other idiosyncratic or individual differences.

Despite these differences in the rate of overall vocalizations between sessions with Liam and George, it is important to note that rate of return vocalizations followed patterns consistent with the rate of overall vocalizations in the original study with no comparison possible on return vocalizations (i.e., not counted in Pelaez et al.). That is, when return vocalizations occurred, they occurred at a higher rate during contingent imitation conditions than during the control conditions. While this finding was not as pronounced with Liam, who only emitted return vocalizations during the initial two sessions with his mother, this may have been due to Liam’s slight delay in speech and difficulties with replicating specific sounds. These findings may lend additional support to the suggestion that caregiver contingent vocalizations function as a reinforcer for infant vocalizations.

One limitation of the current study was the lack of a uniform, highly controlled environment in which sessions occurred. However, conducting naturalistic research that mimics the day-to-day interactions of caregivers and their children may create stimulus properties in the environment that evoke behavior more representative of the behavior the child engages in under conditions where the contingency may occur. This is important because such behavior is likely representative of the behavior emitted during the course of a child’s natural development, whereas behavior in an extremely controlled laboratory setting is apt to be far from what occurs in typical child development (although such settings are necessary for discovering and testing behavioral processes). Another limitation of the current study was the similarity in backgrounds of the three infant participants. These participants were all male, from middle-class households, and lived in suburban areas of Chicago. If reinforcement history is a critical mechanism related to the quantity and quality of emitted infant vocalizations, it is possible that results might have varied if families of differing cultural backgrounds or differing socioeconomic statuses had been included in the study. Given the prevalence of cultural differences, recruitment of families of differing backgrounds may help to strengthen the findings.

In addition, some minor discrepancies in the yoked schedule existed due to stopping the audio recording when infant vocalizations occurred in the control condition, which prevented the caregiver from vocalizing. Nonetheless, as stated above, the number of caregiver vocalizations in control conditions closely approximated the number of caregiver vocalizations during the previous condition for most caregivers in most sessions.

Future research would benefit from conducting baseline measures prior to the start of the experimental sessions. Such a procedural addition would provide the experimenter with baseline rates of infant vocalizations during different day-to-day interactions, as well as the frequency with which the caregiver provides social responses contingent upon the infant’s vocalization. Researchers could also conduct sessions across a longer period of time. As indicated by the amount of distress witnessed in up to six 3-min sessions each day, it may be beneficial to spread out the number of sessions; for example, conducting a full demonstration (i.e., B phase, A phase) with one caregiver and then another with the other caregiver and switching the order of occurrence across days to account for sequence effects. Researchers should also consider including a more diverse participant base, with families from different areas, socio-economic classes, and education levels. It would also be worthwhile to conduct studies on the differences in infant vocalization between caregivers, especially in families where the non-mother caregiver spends much more time with the infant than the mother.

Footnotes

Author note

Jamie L. Hirsh is now a doctoral student in the Department of Psychology, Western Michigan University. This paper is adapted from Jamie Hirsh’s Master’s thesis.

References

- Dunst CJ, Gorman E, Hamby DW. Effects of adult verbal and vocal contingent responsiveness on increases in infant vocalizations. CELLReviews. 2010;3:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein MH, Schwade JA. Social feedback to infants’ babbling facilitates rapid phonological learning. Psychological Science. 2008;19:515–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF, Olson J. Mothers’ and infants’ responses to their partners’ spontaneous action and vocal/verbal imitation. Infant Behavior & Development. 2008;31:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers RE. The role of audition in infant babbling. Child Development. 1988;59:441–449. doi: 10.2307/1130323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez M, Virues-Ortega J, Gewirtz JL. Reinforcement of vocalizations through contingent vocal imitation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:33–40. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulson CL. Differential reinforcement of other-than-vocalization as a control procedure in the conditioning of infant vocalization rate. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1983;36:471–489. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(83)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger HD., Jr . A behavior analytic view of child development. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH, Baumwell L. Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development. 2001;72:748–767. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RH, Iwata BA. A review of reinforcement control procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:257–278. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.176-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]