Abstract

We evaluated the effects of multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) on the relation between listener and intraverbal categorization repertoires of six typically developing preschool-age children using a nonconcurrent multiple-probe design across participants. After failing to emit intraverbal categorization responses following listener categorization training, participants were exposed to MEI in the form of alternating response forms (listener and intraverbal) during categorization training with novel stimulus sets. For two participants for whom there was some evidence of emergent intraverbal responding, responding was variable. For the remaining four participants, 32 to 99 MEI trial blocks produced minimal improvement in responding or no emergent responding at all. The results are discussed in terms of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior and naming theory.

Keywords: Categorization, Intraverbal behavior, Listener behavior, Multiple exemplar instruction, Naming

Curricular targets designed to teach verbal behavior are embedded within early and intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) programs for childhood autism and constitute a large and critically important part of an individual’s curriculum. Some EIBI programs and some clinicians promote and utilize the “verbal behavior approach” to teach language or verbal behavior (Barbera and Rasmussen 2007; Sundberg and Partington 1998). According to the verbal behavior approach, it is not assumed that once an individual learns to emit a word under the influence of one set of controlling variables, she will automatically be able to emit the same word under a different set of controlling variables. This analysis has implications for how language is taught. For example, if an individual is taught to ask for water when she is water deprived (a mand), different manipulations of antecedents and consequences are required to ensure she will be able to emit the same response (water) when shown a picture of a glass of water and asked, “What is this?” (a tact). There is support in the research literature that lends credence to the assertion that the verbal operants are functionally independent from one another and from listener behavior (Gilic and Greer 2011; Lamarre and Holland 1985; Miguel et al. 2005; Petursdottir et al. 2008).

Despite existing evidence demonstrating functional independence across verbal operants, it appears that typically developing individuals eventually learn to respond across verbal operants without explicit training (Skinner 1957; Taylor and Harris 1995). That is, they are able to emit a response under conditions in which they have not received any direct training. However, such emergent responding between verbal operants and between listener and speaker repertoires is notoriously deficient in many individuals with language delays (Guess and Baer 1973; Kelley et al. 2007; Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer 2004). As such, it behooves researchers to develop procedures that generate emergent responding across verbal operants. The result of such research might enhance early intervention curricula such that verbal behavior is taught more comprehensively and efficiently. Multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) represents one way to achieve emergent responding between verbal operants and between listener and speaker repertoires.

One form of MEI consists of alternating instruction between two or more response functions in a subset of exemplars, which results in emergent responding in initially functionally independent verbal operants or response forms (Fiorile and Greer 2007; Greer et al. 2005a, b; Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer 2004). Several studies have examined the effects of this specific form of MEI on emergence across verbal operants or response forms. Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer (2004) tested the effects of MEI on the emergence of untrained mands or tacts of adjective-object pairs in four children with autism. The experimenters presented three sets of adjective-object pairs (e.g., small cup, third box, middle bowl). The participants were taught to either tact or mand for the first or second set of adjective-object pairs. Baseline probes confirmed the absence of the untaught verbal relation (i.e., mands if a tact was taught, and vice versa). MEI was then conducted with a new set of adjective-object pairs. This condition consisted of alternating mand and tact training trials with each adjective-object pair. After MEI, probes were once again conducted with the untrained operant from the original set and a novel set. The authors demonstrated that MEI resulted in high levels of correct responding on the untrained operant from the original and novel sets.

Greer et al. (2005a, b) evaluated the effect of MEI on generating joint control between novel dictation and intraverbal responding with children with language delays.

Using a pre- and post-test similar to the one employed by Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer (2004), the authors observed low levels of the untrained response, vocal or written spelling, in baseline. A subsequent MEI condition resulted in high levels of emergent responding across participants. Greer et al. (2005a, b) replicated these findings with children with language delays targeting vocal and written spelling. It should be noted that the responses targeted in studies that have investigated the effects of the aforementioned iteration of MEI were relatively straightforward (e.g., Greer et al. 2005a, b). In other words, emergent responding was examined across operants in which the target response form was topographically identical (e.g., tacts and mands), across listener responses in the form of pointing and one-word tacts, or across modalities of the same responses (writing and orally spelling a word). Another point to note is that in both the Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer (2004) and Greer et al. (2005a, b) studies, participants were probed only once during baseline before the MEI procedure was introduced, making it challenging to discount maturation as a potential confounding variable. Also, conducting multiple probes during the baseline condition would have helped to control for practice effects. Nevertheless, this line of research provides evidence that MEI may produce functional emergent responding between verbal operants or different response forms (Fiorile and Greer 2007; Greer et al. 2005a, b; Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer 2004).

Categorization skills, which involve more complex forms of responding, are ubiquitous in our daily functioning. They constitute a critical part of an individual’s academic, social, and professional success. For some learners, categorization skills and emergent responding between categorization skills eventually come with apparent relative ease, and minimal or no instruction.

However, for other learners, especially those with language delays and other developmental disabilities, this emergent responding is not easily acquired. Therefore, it is important to identify those procedures that help establish emergent responding between categorization skills. The present study contributes to this endeavor by identifying the limitations of a specific iteration of the MEI procedure in generating emergent responding between listener and intraverbal categorization repertoires. This study was an extension of the Petursdottir et al. (2008) study, which demonstrated that training listener categorization relations did not result in the emergence of intraverbal categorization relations, and vice versa, in typically developing preschool-age children. The purpose of the present study was to determine the effects of MEI on emergent responding between intraverbal and listener categorization repertoires. More specifically, the present study evaluated the effects of MEI on the emergence (or lack thereof) of intraverbal categorization following listener categorization training. The MEI procedure employed in this study was most similar to the Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer (2004) study in which there was one-to-one alternation between the response types of interest per stimulus, with minor differences in the alternation format of the response types.

Method

Participants, Setting, and Materials

Six typically developing children participated in the study; Doug (4 years, 7 months old), Sophie (4 years, 2 months), Alex (4 years, 2 months), Rick (3 years, 10 months), Mike (4 years), and Meredith (4 years, 2 months). English was the participants’ primary language and none had documented developmental delays.

Sessions were conducted at the participants’ preschool in a partitioned corner of the children’s dining area (Doug, Sophie, Alex, Rick) or in an empty preschool classroom (Mike, Meredith). Sessions were conducted one to two times per day, five to ten times per week. One to two graduate students, and one to two undergraduate research assistants were present during each session.

Sessions were conducted at a child-sized table with three to four child-sized chairs. Tokens were delivered for correct responding and appropriate sitting. A small audio recorder was placed on the table within the child’s view. The audio recorder was turned on during sessions to record participants’ vocal behavior. The participants had the opportunity to select a toy or snack from a large plastic tub containing small age-appropriate toys and parent-approved snacks at the end of each session.

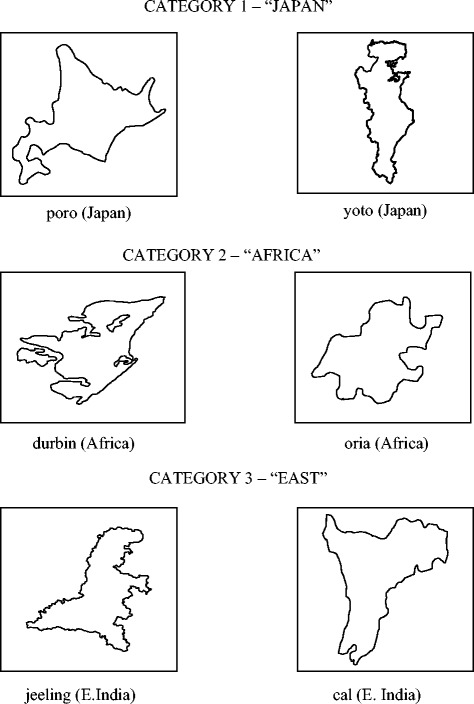

Visual stimuli were presented to participants using three-ring binders. The stimuli were placed on 8.5 × 11 in sheets that were presented in a horizontal manner to the participants. Each sheet was placed inside a page protector. The novel stimuli were outlines of maps of cities or countries and characters from foreign writing systems. Novel stimuli were those stimuli that the participants were unable to tact or receptively identify prior to this study. Familiar stimuli were those stimuli that the participants were able to tact or receptively identify prior to this study. All the stimuli were in black and white. The names of the stimuli were the corresponding names of the cities/countries or characters. Some of the names of the stimuli were modified for ease of pronunciation for the participants (e.g., Poro for Sapporo). The tact training binder contained the stimuli used to train the participants to label (tact) each of the novel stimuli. One picture (stimulus) was depicted on each sheet. The listener training, listener categorization training, and MEI binders contained sheets of three stimuli to which participants would point upon the experimenter’s request (see Fig. 1 for a sample of the visual stimuli presented during the study). Table 1 contains the category names, stimuli names, and set designation for the novel stimuli.

Fig. 1.

Three sample categories and their respective stimuli

Table 1.

Category names, stimuli names, and set designation for novel stimuli

| Category | Members | Set designation |

|---|---|---|

| South | Cochin, Madras | Set 1 |

| Arabic | Kaaf, Baa | Set 1 |

| Greek | Pi, Mega | Set 2 |

| Africa | Durbin, Oria | Set 2 |

| East | Jeeling, Cal | Set 3 |

| Russian | Shah, Yoo | Set 3 |

| Hebrew | Mem, Shin | MEI (A) |

| Sri Lanka | Jaff, Mannar | MEI (A) |

| Armenian | Vev, T’oh | MEI (A) |

| Japan | Yoto, Poro | MEI (A) |

| Swit | Eva, Laus | MEI (B) |

| Rin | Bu, Ka | MEI (B) |

| German | Lub, Bruck | MEI (B) |

| Nese | Yuk, Saan | MEI (B) |

Data Collection

Dependent Variables

The primary dependent variable was the emission of untrained intraverbal categorization responses after initial listener categorization training before and after MEI. For example, after the participant was trained to point to the Japanese character, “Yoto” in response to the instruction, “Which one is Japanese?”, a probe for the participant’s untrained emission of the vocal response “Japanese” in response to the instruction, “Yoto is ___” was conducted. Additionally, data were collected on responses during tact and listener training of the exemplar stimuli, preexperimental listener and intraverbal categorization training with familiar stimuli, listener categorization training of novel stimuli, and listener and intraverbal categorization training of the MEI stimulus sets.

Response Measurement

For all conditions, a response was counted as correct if the participant emitted the target response (a pointing response for all listener targets and a vocal response for all speaker targets) within 10 s of the experimenter’s instruction. A response was counted as incorrect if the participant emitted an incorrect response or did not respond within 10 s of the instruction. Data were analyzed as the total number of correct responses out of set number of possible responses as follows: (a) 8 responses for tact and listener training and categorization training with familiar stimuli, (b) 20 responses for listener categorization training with novel stimuli and intraverbal categorization probes, and (c) 32 responses for MEI.

Interobserver Agreement

A second observer independently collected interobserver agreement (IOA) data across all experimental conditions. An agreement was scored for each trial in which the experimenter and the observer both recorded the same correct or incorrect response. Point-by-point agreement was calculated for each session by dividing the number of agreements by the sum of agreements and disagreements and multiplying by 100. The IOA results for each participant are depicted in Table 2. Agreement was assessed for at least 88 % of sessions and averaged at least 99 % for each participant.

Table 2.

Assessment results for interobserver agreement and procedural fidelity

| Participant | Interobserver agreement (IOA) | Procedural fidelity | Procedural fidelity IOA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doug | 95 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 75–100) | 97 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 75–100) | 63 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 62–100) |

| Sophie | 95 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 87–100) | 95 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 88–100) | 52 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 88–100) |

| Alex | 98 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 75–100) | 96 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 91–100) | 42 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 75–100) |

| Rick | 98 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 87–100) | 99 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 98–100) | 63 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 95–100) |

| Mike | 92 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 88–100) | 92 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 75–100) | 23 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 75–100) |

| Meredith | 88 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 88–100) | 88 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 87–100) | 17 % of sessions, M = 99 % (range 88–100) |

Procedure

General Teaching Procedures

For the conditions that involved motor responses (listener training, listener categorization training of familiar and novel stimuli), pointing to the correct response independently within 10 s of the instruction (e.g., “Which one is East?”), produced enthusiastic praise from the experimenter (e.g., “Wow! That’s right!”). For all conditions that involved speaker behavior (tact training, intraverbal categorization training of familiar and novel stimuli), emission of the correct response independently within 10 s of the instruction (e.g., “What is it?” for tact training, “Yoto is ___” for intraverbal categorization training), produced enthusiastic praise from the experimenter. Tokens were provided on an intermittent schedule of VR 3 contingent on appropriate attending, imitation of the experimenter’s model prompts, and independent responses. If the participant made an incorrect response during conditions that involved motor responses, the experimenter provided gestural and verbal prompts (e.g., “It’s this one. Can you point to it?”). If the participant emitted the incorrect response during tact and intraverbal categorization conditions, the experimenter provided an echoic prompt (e.g., “East. Can you say it?”). Imitation of the experimenter’s model produced praise (e.g., “You’re right!”) and nonresponses or other responses resulted in additional gestural and verbal prompts. After the participant was able to independently emit the correct responses with reinforcement, the experimenter presented the stimuli again under extinction. This way, if correct responses during subsequent probes for the primary dependent variable (intraverbal categorization responding) did not occur or occurred at low rates, it could be concluded with greater confidence that these outcomes were due to a failure to acquire the response and not due to the transition from reinforcement to extinction.

Preliminary Procedures

Upon giving permission for their child to participate, parents were provided a survey to nominate their child’s favorite foods and toys. The results of the survey were used to select toys and snacks that were made available to participants after each session.

Echoic Assessment

The experimenter conducted an informal echoic assessment with each participant to ensure that the participants were able to respond to the echoic prompts that would be used in subsequent conditions.

Tact Training

During the tact training condition, the experimenter taught the participants to vocally tact the stimuli in set 1 (eight stimuli), set 2 (eight stimuli), and MEI A (eight stimuli) for a total of 24 stimuli. Tacts were targeted one set at a time and one trial block included all eight stimuli. Sets 1 and 2 included two categories with two stimuli that corresponded to each category for a total of four target stimuli. Participants were taught to tact stimuli from similar but untrained categories (eight additional stimuli between sets 1 and 2 divided into four stimuli per set) that served as negative comparisons. Additional sets of stimuli were trained if the participants required a second implementation of MEI or if replication sets were required. During each trial, the experimenter presented the stimulus on the table in front of the participant and provided the instruction, “What is it?” Tact maintenance trials were typically conducted every other experimental session in alternation with listener maintenance trials. Maintenance trials were conducted to ensure that participants were able to tact and point to members of the targeted categories throughout the study. After the participants responded correctly with reinforcement at 100 %, trials were conducted under extinction. The mastery criterion was 100 % responding for all eight stimuli under extinction.

Listener Training

The experimenter taught the participants to point to the stimuli in sets 1, 2, and MEI A. Additional sets of stimuli were trained as needed. The experimenter presented the picture of the target stimulus along with two comparison stimuli and instructed the participant to indicate the target stimulus (e.g., “Show me Yoto.”). The mastery criterion was 100 % correct responding for all eight stimuli under extinction.

Listener and Intraverbal Categorization Training Trials with Familiar Stimuli

These trials were conducted with familiar stimuli to ensure instructional control of the trial format over responding when testing with novel stimuli. Categorization testing with familiar stimuli was conducted at the beginning of nearly every session in the entire study except during MEI. Two stimuli from four categories comprised the eight stimuli that were targeted. Categories that were targeted were animals, food, clothes, and toys. Listener categorization training with familiar stimuli involved teaching the participants to point to the stimulus that corresponded to the category indicated in the experimenter’s instruction (e.g., point to the cat in response to the instruction “Which one is an animal?”). After the participants responded correctly with reinforcement at 100 %, trails were conducted under extinction. The mastery criterion was 100 % for all eight stimuli under extinction. Intraverbal categorization training with familiar stimuli involved teaching the participants to emit the name of the category that corresponded to the stimulus indicated in the experimenter’s instruction (e.g., Saying “An animal” in response to the instruction, “A cat is ___.”). After the participants responded correctly with reinforcement at 100 %, trials were conducted under extinction. The mastery criterion was 100 % independent responding for all eight stimuli under extinction, for both listener categorization training and intraverbal categorization training with familiar stimuli.

Listener Categorization Training with Novel Stimuli

This training was conducted with one set of experimental stimuli (four stimuli were targeted and four stimuli served as negative comparisons). Training was identical to the procedure described above except that novel stimuli instead of familiar stimuli were used. After the participants responded correctly with reinforcement at 100 %, trials were conducted under extinction. The mastery criterion for listener categorization training sessions was 100 % independent responding for all 20 stimuli under extinction.

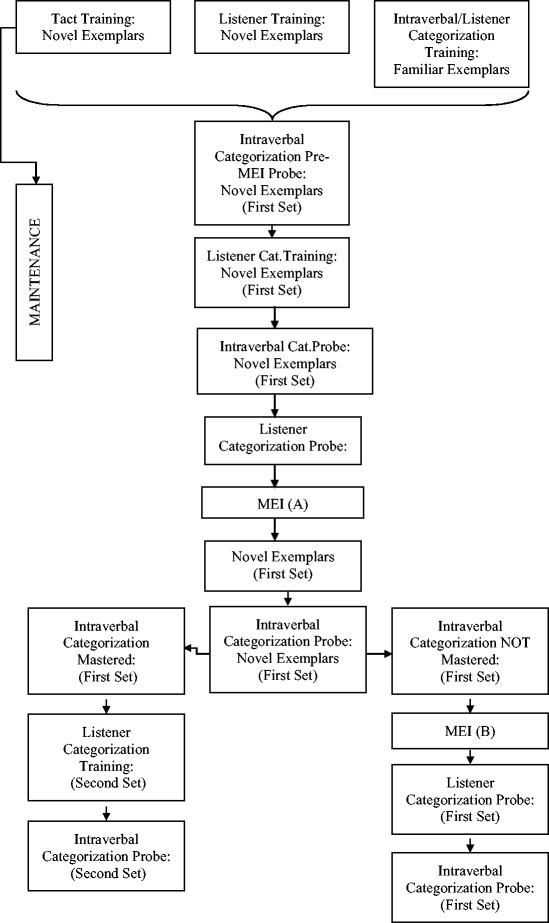

Experimental Evaluation

A nonconcurrent multiple-probe design across participants was used to evaluate the effects of MEI on the relation between intraverbal and listener categorization repertoires. The order of experimental conditions is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The sequence of training and testing conditions

Baseline Probes

After listener categorization training was conducted with one set, intraverbal categorization baseline probes were conducted. Listener categorization training and intraverbal categorization probes were conducted separately. As an example, after training the participant to point to outlines of Durbin and Oria in response to the instruction, “Which one is Africa?” during listener categorization training, a probe during the intraverbal categorization baseline was conducted to determine if the participant emitted the response “Africa” in response to the instructions, “Durbin is…” and “Oria is….” The order of stimulus presentation was randomly rotated across 20-trial blocks during the intraverbal categorization probes to ensure that responding occurred under appropriate stimulus control (i.e., to ensure responding occurred under the influence of the verbal instruction). Correct and incorrect responses did not result in any differential consequences other than the presentation of a new trial. Baseline was conducted until each stimulus within each of the categories (two categories, four stimuli) was presented five times for a total of 20 trials.

MEI with set MEI A

After the baseline condition, MEI was conducted with a second set of stimuli (MEI A). Four categories (eight stimuli, two stimuli per category) were targeted. Blocks of four trials were presented, each of which contained two trials of intraverbal categorization training and two trials of listener categorization training alternating between trial types. Only one stimulus was targeted per trial block. Data were graphed and analyzed as the total number of correct responses out of a possible 16 correct per categorization type (listener and intraverbal) for a 32-trial block. Mastery criterion was 100 % independent responding for one 32-trial block under extinction. Depending on the participant, sessions lasted approximately 15–30 min.

Post-MEI probes

After MEI was conducted with set MEI A, post-MEI test probes for intraverbal categorization responses were conducted again with sets 1 or 2. Before intraverbal categorization probes were conducted, probes for listener categorization responses were conducted to ensure the participants were still responding at mastery criterion. If not, then listener categorization training was conducted until responding to mastery criterion was reachieved. After this, probes for intraverbal categorization responses were conducted. Probes were identical to those described under the baseline condition. If responding for intraverbal categorization responses was at mastery criterion (80 % or higher), then a new set was introduced and tested (e.g., if set 1 was initially used, then listener categorization training and intraverbal categorization probes were conducted with set 2). If responding met the mastery criterion during intraverbal categorization probes for set 1, listener categorization training was conducted with a new set (e.g., set 2). Prior to listener categorization training with set 3 for Sophie, an intraverbal categorization probe was conducted with set 3. This step was conducted to demonstrate that the participant was unable to emit intraverbal categorization responses prior to listener categorization training. This step was not conducted with Doug due to experimenter error. Given the esoteric nature of the targeted stimuli, however, it is unlikely that Doug would be able to emit intraverbal categorization responses for sets 2 and 3 in the absence of listener categorization training. Listener categorization training then was conducted with set 2. Immediately after responding met the mastery criterion during listener categorization training, probes for intraverbal categorization responses were conducted for sets 2 or 3. Each stimulus in the set (two categories, four stimuli total) was presented five times each for a total of 20 presentations. These data were analyzed and reported as the total number of correct responses out of a possible 20 responses. If the probes for intraverbal categorization responding were at 80 % or higher for 20 total presentations, the participant was dismissed from the study.

MEI with set MEI B

If responding during intraverbal categorization probes after MEI for sets 1 or 2 was not at mastery criterion, additional MEI was conducted with a new set (MEI B) which contained four categories. This initially involved tact and listener training for all eight stimuli. After MEI was conducted to mastery criterion for set MEI B, probes were conducted again with sets 1or 2. Before the intraverbal categorization probes were conducted, probes for listener categorization responding were conducted to ensure the participants were still responding at mastery level. As described above, if intraverbal categorization responding was at mastery criterion (80 % or higher), then a new set (e.g., set 2 or 3) was introduced at this time in an attempt to replicate the effects of MEI. If mastery-level responding was not achieved after a second implementation of MEI with set MEI B, then the participant was dismissed from the study.

Procedural Fidelity

A secondary observer scored a trial correct if the experimenter delivered the instruction, prompts, and consequences appropriate to the phase and the child’s response. A procedural integrity score was then computed for each session as the percentage of correctly implemented trials. Point-by-point IOA was assessed on all procedural fidelity measures. Procedural fidelity scores and their corresponding IOA data are depicted in Table 2. Procedural fidelity was assessed for at least 88 % of sessions and averaged at least 99 % for each participant. Interobserver agreement on procedural fidelity data was assessed for at least 17 % of sessions and averaged at least 99 % for each participant.

Results

Tact and Listener Training

The results of the tact and listener training conditions are depicted in Table 3. The table includes the total number of trial blocks required to acquire all of the tact and listener stimulus sets, the number of sets taught, the total number of stimuli, and the mean number of trial blocks required to acquire each set. Participants acquired the tact sets in 92 to 147 trial blocks, and the listener sets in 4 to 8 trial blocks.

Table 3.

Results for tact training, listener training, and listener/intraverbal categorization training (familiar stimuli)

| Participant | Tact training | Listener training | Listener/intraverbal categorization training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doug | 95 trial blocks (M = 23) 4 sets 32 stimuli |

8 trial blocks (M = 2) 4 sets 32 stimuli |

2 trial blocks No errors with either categorization type Emitted an echoic and a tact during a listener categorization triala |

| Sophie | 122 trial blocks (M = 26) 5 sets 40 stimuli |

5 trial blocks (M = 1) 5 sets 40 stimuli |

3 trial blocks Errors with intraverbal categorization |

| Alex | 139 trial blocks (M = 35) 4 sets 32 stimuli |

7 trial blocks (M = 2) 4 sets 32 stimuli |

2 trial blocks Errors with intraverbal categorization |

| Rick | 92 trial blocks (M = 23) 4 sets 32 stimuli |

4 trial blocks (M = 1) 4 sets 32 stimuli |

4 trial blocks Errors with intraverbal and listener categorization |

| Mike | 147 trial blocks (M = 29) 5 sets 40 stimuli |

5 trial blocks (M = 1) 5 sets 40 stimuli |

5 trial blocks Errors with intraverbal categorization |

| Meredith | 106 trial blocks (M = 21) 5 sets 40 stimuli Provided the name of the correct category, instead of the name of the stimulus itself during a maintenance triala |

7 trial blocks (M = 1) 5 sets 40 stimuli |

4 trial blocks Errors with intraverbal and listener categorization |

aCollateral verbal behavior of interest

Listener and Intraverbal Categorization Training (Familiar Stimuli)

The results for the listener and intraverbal categorization training condition with familiar stimuli for each participant are depicted in Table 2. The table includes the total number of trial blocks required to acquire listener and intraverbal categorization with familiar stimuli, whether the participant made errors with each categorization type and any interesting collateral verbal behavior. Participants acquired the target listener and intraverbal categorization relations in two to five trial blocks.

Listener Categorization Training (Novel Stimuli)

The results for the listener categorization training condition with novel stimuli for each participant are depicted in Table 4. The table includes the total number of sets taught and the number of trials blocks required to master each set. Participants acquired the target listener categorization relations in four to eight trial blocks per set.

Table 4.

Results for listener categorization training and multiple exemplar instruction

| Participant | Listener categorization training (novel stimuli) | Multiple exemplar instruction |

|---|---|---|

| Doug | Set 1 = 5 trial blocks Set 2 = 4 trial blocks Set 3 = 4 trial blocks |

Set A = 14 trial blocks |

| Sophie | Set 1 = 5 trial blocks Set 3 = 7 trial blocks |

Set A = 37 trial blocks Set B = 33 trial blocks |

| Alex | Set 2 = 4 trial blocks Echoed the word “East” in two trialsa |

Set A = 43 trial blocks Set B = 56 trial blocks |

| Rick | Set 1 = 4 trial blocks | Set A = 40 trial blocks Set B = 32 trial blocksb |

| Mike | Set 1 = 8 trial blocks | Set A = 17 trial blocks Set B = 15 trial blocks |

| Meredith | Set 1 = 8 trial blocks | Set A = 20 trial blocks Set B = 17 trial blocks |

aCollateral verbal behavior of interest

bModified mastery criterion

Multiple Exemplar Instruction

Each participant’s MEI data are depicted in Table 4. The table includes the total number of trial blocks required to acquire each MEI set and collateral verbal behavior of interest. Participants completed MEI in 14 to 56 trial blocks per set.

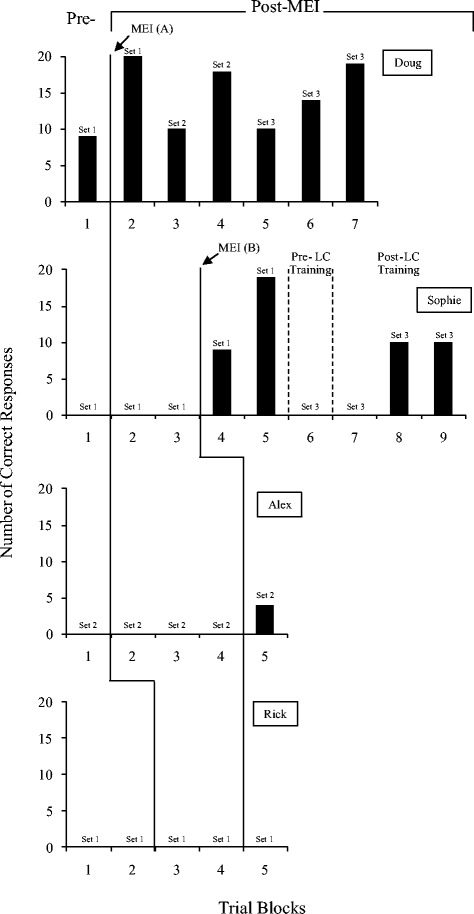

Primary Experimental Evaluation (Intraverbal Categorization Probes)

Baseline (Pre-MEI)

Results for all six participants’ performance during intraverbal categorization probes pre- and post-MEI training are depicted in Figs. 3 and 4. During baseline, Doug scored 45 % correct for set 1, occasionally responding with targets from both categories. The remaining five participants scored 0 % during baseline.

Fig. 3.

Number of correct responses during intraverbal categorization probes before and after multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) for Doug, Sophie, Alex, and Rick. LC listener categorization

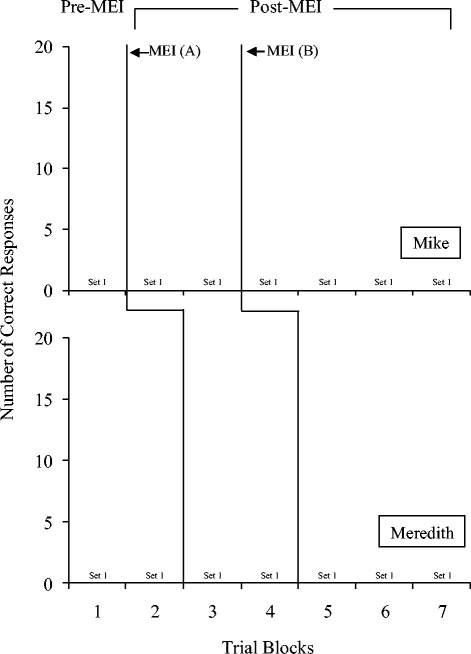

Fig. 4.

Number of correct responses during intraverbal categorization probes before and after multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) for Mike and Meredith

Post-MEI probes after MEI A

After ensuring listener categorization responses for set 1 and MEI A responses were still at mastery, intraverbal categorization probes were conducted. Doug responded with 100 % accuracy under extinction during the first post-MEI probe. In attempts to replicate these effects, probes were conducted with sets 2 and 3. Doug scored 50 % in the first set 2 probe. A second probe with set 2 resulted in a score of 90 %. In response to these mixed results, another intraverbal categorization probe was conducted with set 3. During the first probe with set 3, Doug scored 50 %, and with a second probe, Doug scored 70 %. Given these mixed results, a third set 3 probe was conducted in which Doug responded at 95 % correct.

For Sophie, two probes with set 1 each resulted in a score of 0 % correct. During both probes, Sophie shrugged during each trial and said “I don’t know these” or “I don’t know.” Alex’s three post-MEI A probes with set 2 each resulted in scores of 0 %. During the third post-MEI A probe, he repeatedly said, “I don’t know” and “nothing.” Rick’s two post-MEI A probes with set 1 each resulted in scores of 0 %. During the first of these probes, Rick emitted the exemplar and category names for stimuli targeted during tact and MEI A training (e.g., brew, lanka, and yoo) for 8 out of the 20 trials. Neither of the category names (brew and lanka) was correct for set 1. During the second post-MEI A probe, he emitted three exemplar names (madras, senza, and chi) one time each, and then names of random common stimuli not targeted in the study (e.g., apple head and pancake) for 13 trials. Mike’s two post-MEI A probes with set 1 each resulted in a score of 0 %. On many occasions, he imitated the stimulus in the experimenter’s instruction. Meredith’s two post-MEI A probes with set 1 each resulted in a score of 0 %.

Post MEI (B)

A second implementation of MEI (MEI B) was conducted with Sophie, Alex, Rick, Mike, and Meredith. During the first of these probes for set 1, Sophie scored 45 %.

During the second probe with set 1, Sophie scored 95 %. In an effort to replicate the effects achieved with set 1, intraverbal categorization probes were conducted with set 3. The first intraverbal categorization probe resulted in a score of 0 %. After listener categorization training, the first intraverbal categorization probe resulted in a score of 0 %. Two more intraverbal categorization probes with set 3 resulted in a score of 50 %. Alex scored 20 % on his post-MEI B intraverbal categorization probe with set 2 during which he emitted category names targeted during MEI A and B. Rick, Mike, and Meredith scored 0 %, during post-MEI B probes for set 1.

Discussion

The results of the present study extend the literature on MEI by demonstrating that it was not reliably effective in producing emergent responding between listener and intraverbal categorization repertoires in six typically developing children between the ages of 3 and 4 years. It is possible that MEI failed to produce emergent responding between the targeted verbal operants in the present study because of the more complex nature of the repertoires involved (i.e., categorization). This study represents a starting point for MEI procedures and their utility for producing emergent responding for more complex forms of responding.

Doug may have engaged in covert responding that produced the emergent intraverbal categorization responding observed during baseline and post-MEI probes. A consideration of the Naming theory is warranted. When an individual has learned to respond to a given stimulus as both a speaker and a listener, it can be said that he has acquired naming (Horne and Lowe 1996; Lowe et al. 2002). A critical feature of the naming account is that many stimuli may come to produce a common speaker and listener response, implicating the naming relation in the establishment of categorization (Horne et al. 2004; Lowe et al. 2005; Miguel et al. 2008). During listener categorization training, when the experimenter asked Doug, “Which one is Africa?,” he was taught to point to the outlines of the cities Durbin and Oria. While pointing to Durbin and Oria, he may have responded to his own listener behavior (pointing to the picture of Durbin and Oria) as a speaker and covertly tacted the exemplar and echoed the corresponding category (“Durbin, Africa” and “Oria, Africa”). During intraverbal categorization probes, the experimenter asked Doug “Durbin is ___?,” during which time he may have engaged in covert responding “Durbin, Africa,” established during listener categorization training, and then emitted the response “Africa.” Teaching Doug to respond to both Durbin and Oria as a listener to a common name (Africa) may have then resulted in Doug responding to both Durbin and Oria as a speaker using a common name (Africa). The auditory stimulus “Durbin,” served as a stimulus common to both instructional contexts, possibly resulting in stimulus control over responding in both instructional contexts (listener and intraverbal categorization) and influencing the establishment of emergent responding. While consideration of the Naming theory offers a cohesive and parsimonious explanation for Doug’s performance, this account remains speculative as there was no evidence of covert responding and functional control was not demonstrated over the post-MEI response increases.

Sophie required exposure to two sets of MEI, which yielded comparatively little emergent responding. The reverse categorization relation was originally examined with Sophie. That is, the intraverbal categorization repertoire was trained and listener categorization responses were probed. These data are not graphed. When the experimenter probed listener categorization responses during baseline, she demonstrated 100 % emergent responding providing evidence of emergent responding between the two categorization types in one direction (from intraverbal to listener), indicating an emerging Naming relation for Sophie. For Sophie, perhaps hearing both the exemplar name and the category name (e.g., “Durbin is Africa”) exerted greater control over responding during listener categorization probe trials than was the case with the reverse relation. During listener categorization training, the experimenter provided only the auditory stimulus of the category name (e.g., “Africa”). Maybe learners with a more extensive history with respect to categorization, like Doug, are more likely to tact, overtly or covertly, the exemplar name (e.g., “Durbin”) during listener categorization training trials than those learners who have less experience with categorization. As such, the learner produces an additional relevant auditory stimulus during listener categorization (“Durbin”) that will be present during intraverbal categorization probes (“Durbin is ____”), which would subsequently increase the likelihood of emergent responding between the two categorization types.

Rick and Alex required a large number of training trials to learn two sets of MEI. Despite training two sets of MEI, there was very little to no emergent responding, suggesting a weak or nonexistent naming repertoire. Rick was nearly 1 year younger than Doug and the only participant under the age of 4 years at the start of the study. This may be important when considering the types of skills typically targeted with children between the ages of 3.5 and 4.5 years in daycare and preschool, which commonly include tacts, listener responses (matching and pointing), and categorization. Three to 9 months of experience with these skills can make a difference with respect to developing the verbal behavior necessary to establish a naming repertoire and produce emergent responding.

Mike and Meredith required training with two sets of MEI, which ultimately did not produce emergent responding between listener and intraverbal categorization repertoires. Mike and Meredith acquired mastery of MEI in few trials and their performances with this task resembled that of Doug’s. However, it may have been the case that not only could Doug produce the relevant verbal behavior (e.g., tact the name of the stimulus and echo the name of the category during listener categorization training trials) but perhaps he also used a rehearsal strategy such that he was able to later emit the responses during intraverbal probe trials. It may have been the case that Mike and Meredith were not employing a rehearsal strategy, or at least not doing so consistently, and this contributed to the failure to produce emergent intraverbal categorization responding. Three to 4-year-old children typically do not use rehearsal strategies and often just keep track of physical stimuli (Novak and Pelaez 2004). At around 5 years of age, children start to use rehearsal as a strategy (Novak and Pelaez 2004). Mike and Meredith were close to 4 years, and Doug was 4 years and 7 months at the start of the study. This age difference with Doug may be significant in that Doug may have already begun to use rehearsal strategies, while Mike and Meredith had not.

A few limitations of the current study are worth acknowledging. One limitation may have been the probe trial format failing to effectively evoke desired responding, especially as it pertained to Sophie’s and Mike’s performances. Just as members of a response class can produce the same consequence, so too can the topographically varied members of a functional stimulus class influence the same response (McIlvane and Dube 2003). Researchers endeavor to use stimuli that they assume will control the responding of the participant. Sometimes there are features of stimuli that the researcher may not detect or consider that control the responding of the participant. One of these features may include trial format or presentation. Although the format of the listener and intraverbal categorization trials during training with familiar stimuli was the same as during listener training and intraverbal probes with novel stimuli, the trials were presented in an alternating format, as was the case during MEI. However, during listener categorization training with novel stimuli and during intraverbal categorization probes with novel stimuli, these trials were presented all at once and not in an alternating format. It may have been the case that these presentation differences ultimately negatively impacted their performances. Future studies may, for example, present the listener categorization trials and the intraverbal categorization trials with familiar stimuli separately, mimicking the training and probe trial formats, instead of presenting them in an alternating trial format as was done in the current study, which mimicked the MEI trial format.

A second possible limitation may have been the one-to-one alternating trials format of the MEI training procedure. Due to the fact that each stimulus was targeted in four-trial blocks with alternation between response type, and hence close temporal proximity of trials of each response type, it could have been the case that intraverbal categorization responding came under echoic control of the experimenter emitting the stimulus name, and not under control of the intraverbal frame. However, due to the stringent response criteria (responding within 10 s of the experimenter’s instruction), and rapid alternation between trial blocks, this is highly unlikely, and it is more likely that responding during intraverbal categorization trials was under discriminative control of the intraverbal frame.

A third limitation may have been that the mastery criterion for MEI was especially stringent (100 % correct trials under extinction) and the number of targets included in MEI (32 targets) may have been too great for this young population. As a result, it took a long time for participants to reach the mastery criteria, which may have affected motivation during experimental trials. A modification of the mastery criterion for MEI was even required for one participant. It may have been the case that waning motivation over time affected attending responses which in turn negatively impacted intraverbal categorization responding. Future research studies in this area may consider using half the number of targets during MEI training (e.g., 16 trials, two categories) and reducing the MEI mastery criterion to 80 or 90 %.

Future research might also examine the effects of directly training exemplar and category tacts during MEI to generate emergent responding between listener and intraverbal categorization repertoires. During listener categorization training trials, it may be more effective to train the pointing response, and the autoclitic frame “Stimulus is Category.” For example, the experimenter would provide the discriminative stimulus, “Which one is Africa?” and then train the participant to point to “Durbin,” then vocalize the statement “Durbin is Africa.” Although previous research has indicated that echoic, multiple-tact, and receptive discrimination training does not significantly influence the emission of intraverbal behavior (Miguel et al. 2005; Petursdottir et al. 2014), perhaps embedding this training as an autoclitic frame in an alternating format with intraverbal categorization trials in the context of MEI may teach the child to emit relevant responses that would generate stimulus control over categorization responding and result in emergent intraverbal categorization.

Finally, future research may also want to examine the effects of this study’s iteration of MEI and its effectiveness in producing emergent listener categorization responses after training intraverbal categorization responses. It may be the case that this study’s iteration of MEI is effective contingent on a given training sequence (expressive before receptive instead of receptive before expressive). As mentioned previously, Sophie was able to emit all listener categorization responses after initial intraverbal categorization training. For individuals who do not demonstrate emergence, it may be the case that this study’s MEI procedure is effective in producing emergent responding if the expressive (intraverbal) categorization response were trained first. The outcomes of a study like this may also make some helpful contributions to the literature on expressive and listener responses and training sequences (Petursdottir and Carr 2011).

Previous studies found MEI to be effective when the trained responses was topographically identical to the probed responses (Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer 2004) or when acquisition of the necessary behavior to produce emergent responding was more straightforward, as is the case between pointing and matching responses, and tact responses (Greer et al. 2005a, b). However, generating emergent responding between categorization repertoires may be more complex and may require the previously described modifications to the MEI procedure to successfully generate emergent responding between listener and intraverbal categorization.

Footnotes

This article is based on a dissertation submitted by the first author, under the supervision of the second author, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree in psychology at Western Michigan University. We thank Jesse Slappey, Chiara Cunningham, Jennifer Davis, Tania Gonzales, Rachel Wagner, Dylan Churchwell, Kerry Conde, Laura Reisdorf, Nicole Shriver, Jodie Newsome, Jacquelin Jackson, Sean Reynolds, James Mellor, Jackie Hoag, Abby Mercure, Courtney Fox, Rob Long, Taylor Butts, Adam Freeman, Chris Zielinski, Megan Baumgartner, and Cindy Han for their assistance with data collection and conducting sessions. Finally, we thank Pat Oldham, Lori Sebright, Pamela Kelly, and Kathy Graff for their invaluable on-site support.

References

- Barbera ML, Rasmussen T. The verbal behavior approach: How to teach children with autism and related disorders. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorile CA, Greer RD. The induction of naming in children with no prior tact responses as a function of multiple exemplar histories of instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2007;23:71–87. doi: 10.1007/BF03393048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilic L, Greer RD. Establishing naming in typically developing two-year-old children as a function of multiple exemplar speaker and listener experiences. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:157–177. doi: 10.1007/BF03393099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Stolfi L, Chavez-Brown M, Rivera-Valdes C. The emergence of the listener to speaker component of naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:123–134. doi: 10.1007/BF03393014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Yaun L, Gautreaux G. Novel dictation and intraverbal responses as a function of a multiple exemplar instructional history. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:99–116. doi: 10.1007/BF03393012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guess D, Baer DM. An analysis of individual differences in generalization between receptive and productive language in retarded children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1973;6:311–329. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1973.6-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne, P. J., & Lowe, C. F. (1996). On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 65, 185–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF, Randle VRL. Naming and categorization in young children: II. Listener behavior training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;81:267–288. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.81-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ME, Shillingsburg MA, Castro MJ, Addison LR, LaRue RH., Jr Further evaluation of emerging speech in children with developmental disabilities: training verbal behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:431–445. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarre J, Holland JG. The functional independence of mands and tacts. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1985;43:5–19. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.43-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe CF, Horne PJ, Harris FDA, Randle RL. Naming and categorization in young children: vocal tact training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:527–549. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe CF, Horne PJ, Hughes JC. Naming and categorization in young children: III. Vocal tact training and transfer of function. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2005;83:47–65. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.31-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane WJ, Dube WV. Stimulus control topography coherence theory: foundations and extensions. The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:195–213. doi: 10.1007/BF03392076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel CF, Petursdottir AI, Carr JE. The effects of multiple-tact and receptive-discrimination training on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:27–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03393008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel CF, Petursdottir AI, Carr JE, Michael J. The role of naming in stimulus categorization by preschool children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2008;89:383–405. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2008-89-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak G, Pelaez M. Child and adolescent development. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzolo-Gomez R, Greer RD. Emergence of untaught mands or tacts of novel adjective-object pairs as a function of instructional history. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;20:63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03392995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petursdottir AI, Carr JE. A review of recommendations for sequencing receptive and expressive language instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:859–876. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petursdottir AI, Carr JE, Lechago SA, Almason SM. An evaluation of intraverbal training and listener training for teaching categorization skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:53–68. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petursdottir AI, Lepper TL, Peterson SP. Effects of collateral response requirements and exemplar training on listener training outcomes in children. The Psychological Record. 2014;64:703–717. doi: 10.1007/s40732-014-0051-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML, Partington JW. Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Pleasant Hill: Behavior Analysts; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, Harris SL. Teaching children with autism to seek information: acquisition of novel information and generalization of responding. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:3–14. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]