Abstract

Several researchers have compared the effectiveness of tact or textual prompts to echoic prompts for teaching intraverbal behavior to young children with autism. We extended this line of research by comparing the effectiveness of visual (textual or tact) prompts to echoic prompts to teach intraverbal responses to three young adults with autism. An adapted alternating treatments design was used with 2 to 3 comparisons for each participant. The results were mixed and did not reveal a more effective prompting procedure across participants, suggesting that the effectiveness of a prompting tactic may be idiosyncratic. The role of one’s learning history and the implications for practitioners teaching intraverbal behavior to individuals with autism are discussed.

Keywords: Adults, Autism, Echoic, Intraverbal training, Prompting procedures, Tact, Textual

Several researchers have compared the efficiency of visual (i.e., tact or textual) and echoic prompts within fading or transfer-of-control procedures to teach intraverbal behavior to young children with autism. Three of the five studies indicated textual or tact prompts were more efficient (Finkel and Williams 2001; Ingvarsson and Hollobaugh 2011; Vedora et al. 2009). Possible explanations for the relative greater efficiency of these visual prompts include decreased social interactions involved with their use as compared to echoic prompts (Finkel and Williams 2001), participants’ prior histories with echoic prompts that failed to bring intraverbal responding under appropriate stimulus control (Finkel and Williams 2001; Vedora et al. 2009), procedural variables such as longer exposure to visual prompts compared to echoic prompts (Finkel and Williams 2001; Vedora et al. 2009), and visual imagining that was occasioned by the use of the tact prompts (Ingvarsson and Hollobaugh 2011).

Other researchers have found that the echoic prompts resulted in faster acquisition of intraverbal behavior for several young children with autism (Ingvarsson and Le 2011; Kodak et al. 2012). Ingvarsson and Le (2011) suggested that their participants’ extensive exposure to vocal prompts and transfer-of-control procedures likely accounted for the greater efficiency of the echoic condition, a notion supported by the findings of Coon and Miguel (2012) who found that participants’ recent history with prompting tactics affected which modality was more efficient. Kodak et al. (2012) suggested their participants benefited from an error correction procedure that allowed for additional opportunities for the echoic behavior to come under the proper stimulus control.

Overall, the existing research does not indicate a superior prompting strategy for teaching intraverbals to young children with autism. The research related to intraverbal instruction for young adults, including comparative evaluations of prompting tactics, is very limited (Sundberg et al. 1990). The purpose of the present study was to directly compare the use of textual or tact prompts to echoic prompts, used with transfer-of-control procedures, when teaching intraverbal repertoires to three young adults with autism.

Method

Participants, Setting, and Materials

The participants were three Caucasian individuals who spoke English, all of whom were diagnosed with autism by a professional unassociated with the study. Anna was a 19-year-old female whose verbal repertoire consisted of four-to-five word echoics and mands, tacts, and intraverbals of five- to six-word sentences. She answered approximately 25 questions related to personal information, recent events, and features or functions of objects. James was a 21-year-old male whose verbal repertoire was comprised of one-to-two word echoics and mands, tacts, and intraverbals of three- to five-word sentences. He answered approximately 30 questions related to personal information, recent and future events, and feature, function, and class for numerous items. James also emitted approximately 50 sight words. Mike was a 20-year-old male whose verbal repertoire consisted of two-to-three word echoics and mands, tacts, and intraverbals of two- to four-word sentences. He answered approximately 10 questions related to personal information and recent events, but he did not answer questions related to features or functions of objects. Echoic prompts were used exclusively for intraverbal instruction within each participant’s classroom for at least 2 years prior to the study.

Stimulus cards were used to present the tact or textual prompts in the tact and reading pretests. The pictures were laminated white paper (approximately 7.62 cm by 12.7 cm), and the textual cards were white index cards with the response printed in black 72-point Arial font. All sessions occurred at a residential school for individuals with autism and developmental disabilities. Anna’s sessions were conducted in her classroom while James’ and Mike’s sessions were conducted in a small training room or conference room. Sessions occurred 5 days per week and were approximately 5 min in duration.

Dependent Variable and Measurement

The primary dependent measure was the percentage of independent correct responses. An independent correct response was defined as the participant providing the correct answer prior to a scheduled prompt within 5 s of the verbal stimulus (i.e., question). An incorrect response was defined as the participant stating the wrong answer to a question or failing to respond within 5 s of the question or prompt when the time delay was in effect. Only the participant’s first response was scored; the response to an error correction was not scored. The mastery criterion was two consecutive sessions with 90 % independent correct responses on the initial trial.

A second observer independently collected trial-by-trial data in 66, 64, and 38 % of sessions for Anna, James, and Mike, respectively. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of trials with an agreement by the total number of trials for each session and converting the ratio to a percentage. Mean interobserver agreement was 99.1 % for Anna (range, 90–100 %), 99 % (range, 80–100 %) for James, and 100 % for Mike. Procedural integrity data were also collected by an independent observer in 66, 64, and 38 % of sessions for Anna, James, and Mike, respectively. Procedural integrity was calculated by dividing the total number of correct steps by the total number of steps and converting the ratio to a percentage. Mean procedural integrity was 99.4 % (range, 93–100 %) for Anna, 98.6 % (range, 93–100 %) for James, and 99.6 % (range, 97–100 %) for Mike.

Procedures

Pretests

Questions were identified based on objectives in each participant’s Individualized Education Plan. An intraverbal pretest was conducted in which each question was presented five times in random order across three blocks of 10 trials. Correct responses resulted in praise. There were no programmed consequences for incorrect responses. Questions that were answered incorrectly on all five assessment trials were considered unknown. A brief echoic pretest was conducted in which each stimulus was presented 10 times to ensure the participants could echo the words and articulate them clearly. A tact or reading pretest was also implemented to confirm that the participants could tact the pictures or read the text. Questions were divided into sets based on length of both the question and the response as these were presumed to be indicative of the level of difficulty. After sets were established, the questions were randomly assigned to experimental conditions.

Baseline

The target question was presented 10 times, with two previously learned non-target questions interspersed between each trial for a total of 30 trials within a session. The non-target questions were intraverbal responses the participants had acquired prior to this experiment (e.g., What is your name? How old are you? What do you do with this object?). No prompts were delivered, and no programmed consequences followed correct or incorrect responses for the target questions. Verbal praise was delivered for correct responses on non-target questions.

Prompt Comparison

The questions and answers assigned to each condition are presented in Table 1. During each comparison, one target question was assigned to each condition. Each session consisted of 10 instructional trials of the target question and two previously learned questions (i.e., intraverbals) interspersed between each instructional trial for a total of 30 trials. The order of the three questions within a group varied in each trial. All prompted correct responses on instructional trials were reinforced during the first two training sessions with verbal praise and delivery of an edible that was identified in a brief choice opportunity prior to each session. Beginning in the third teaching session, all prompted correct responses during instructional trials resulted in the delivery of verbal praise and independent correct responses were reinforced with an edible paired with praise. During all sessions, correct responses on the previously learned questions that were interspersed resulted in verbal praise. If the participant made an error on an instructional trial, the instructor repeated the question and provided an immediate prompt, the type of which depended on the training condition. Neither verbal praise nor the edible reinforcer was delivered following the participant’s response to the error correction procedure. The error correction procedure was conducted once, and if the participant made an error during the correction procedure, the experimenter moved on to the next trial. If the participant did not respond to a prompt within 5 s, the experimenter moved on to the next trial. However, during the echoic, tact, and textual conditions, all participants always responded to a prompt within 5 s.

Table 1.

Questions (Q) and answers (A) for each participant

| Participant | Tact or textual prompts | Echoic prompts |

|---|---|---|

| Anna | Set 1 Q: “What do you eat with?” A: “Fork” | Q: “What do you hear with?” A: “Ears” |

| Set 2 Q: “What do you use to tell time?” A: “Clock” | Q: “What do you use to wash?” A: “Soap” | |

| Set 3 Q: “What do apples grow on?” A: “Tree” | Q: “What is ice made of?” A: “Water” | |

| James | Set 1 Q: “What is ice made of?” A: “Water” | Q: “What do you stir with?” A: “Spoon” |

| Set 2 Q: “Who lives on a farm?” A: “Pig” | Q: “Name a fruit.” A: “Apple” | |

| Mike | Set 1 Q: “What is ice made of?” A: “Water” | Q: “What do you see with?” A: “Eyes” |

| Set 2 Q: “What do you use to wash?” A: “Soap” | Q: “What do you use to tell time?” A: “Clock” |

During the initial training session for each target question, an immediate prompt (0-s delay) was used on the first two instructional trials. If the participant responded correctly with the prompt, a progressive time delay was implemented. On the third instructional trial, the prompt was provided 1 s after the question. After two consecutive independent correct responses, the time delay was increased by 1 s, up to a 5-s delay. If the participant responded incorrectly twice within the session, the prompt interval was reduced by 1 s. Each subsequent session began at the prompting interval at which the previous session ended.

Echoic Prompts

The experimenter presented the question and stated only the word that the student should say. The prompt was removed using the progressive time delay procedure described above.

Tact or Textual Prompts

The training procedure was exactly the same as the echoic condition except the experimenter presented a picture or a textual prompt (James). The instructor held the picture or textual prompt at the participants’ eye level approximately 60–70 cm away until the participants responded for a maximum of 5 s.

Final Best Treatment

For James, the echoic prompts were changed to textual prompts after the criterion was met in the other condition due to a decelerating trend during training of the target question in Set 1.

Follow-up

Follow-up probes were conducted after 2 to 6 months for Anna and James. Each session consisted of 10 trials with two previously learned non-target questions interspersed between the target questions. No prompts were delivered during the follow-up sessions. Independent correct responses resulted in verbal praise while errors were corrected using the correction procedure described above.

Experimental Design

An adapted alternating treatments design (Sindelar et al. 1985) was used to compare the efficiency of tact or textual prompts to that of echoic prompts. The order of conditions was varied semi-randomly (i.e., no condition could occur for more than two consecutive sessions). There were three comparisons completed with Anna and two comparisons for James and Mike.

Results

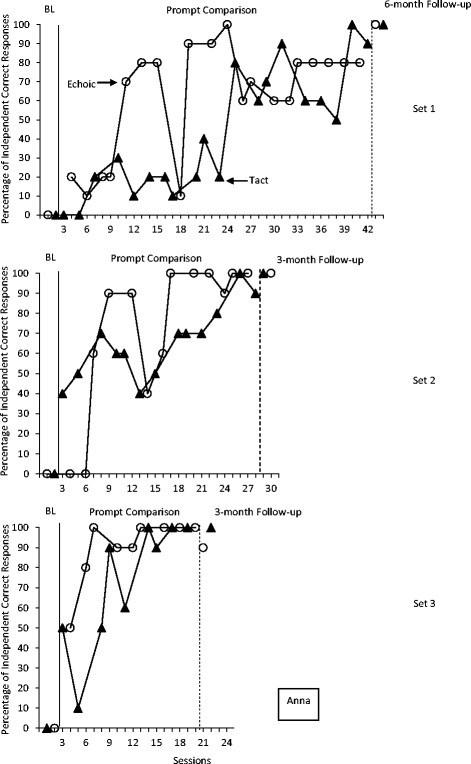

The results for Anna are displayed in Fig. 1. Anna did not answer any questions correctly in baseline for Set 1, 2, or 3. During training on Set 1, Anna’s responding was variable but she met the mastery criterion after 10 sessions in the echoic condition and 20 sessions in the tact condition. For Set 2, Anna met the mastery criterion after five sessions in the echoic condition and 13 sessions in the tact condition. For Set 3, Anna met the mastery criterion after five sessions in the echoic condition and seven sessions in the tact condition. Anna maintained the target responses at 90–100 % independent correct during the 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments.

Fig. 1.

The percentage of independent correct responses for Sets 1, 2, and 3 for Anna during baseline, prompt comparison, and follow-up conditions

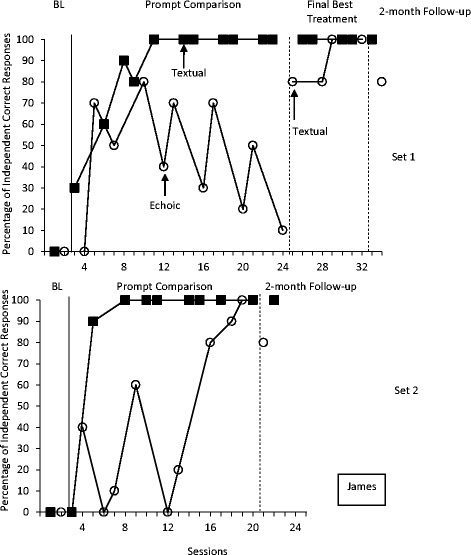

The results for James are displayed in Fig. 2. James did not answer any questions correctly during baseline for Sets 1 and 2. For Set 1, James met the mastery criterion in the textual condition in 7 sessions. In the echoic condition, James failed to meet the mastery criterion after 11 sessions. The prompt was then changed to a textual prompt and James subsequently met the criterion after four sessions. For Set 2, James met the criterion after three sessions in the textual condition and nine sessions in the echoic condition. James maintained responses at 80–100 % independent correct during the 2-month follow-up assessments.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of independent correct responses for Sets 1 and 2 for James during baseline, prompt comparison, final best treatment, and follow-up conditions

The results for Mike are displayed in Fig. 3. Mike did not answer any questions correctly during baseline for Sets 1 and 2. Mike met the mastery criterion in both conditions after seven and four sessions for Set 1 and Set 2, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The percentage of independent correct responses for Sets 1 and 2 for Mike during baseline and prompt comparison conditions

Discussion

The results of the present study were mixed and did not indicate a more efficient prompting tactic across the three participants. The current study extends previous research comparing prompting procedures to teach intraverbals to three young adults with autism. Notably, the procedure for the echoic condition differed from prior research as the instructors did not include the word “say” prior to delivering the vocal prompt. This resulted in prompting conditions that were better equated (Ingvarsson and Hollobaugh 2011). That is, it is possible in prior studies that included the additional instruction “say” that was present in the echoic condition but not the visual condition was partly responsible for the increased effectiveness of the echoic prompts as it provided the learner with an explicit instruction to speak.

Given the mixed results in the present study and in the prior research comparing prompting tactics during intraverbal instruction, it seems likely that the relative efficiency of a tactic is idiosyncratic across individuals (Ingvarsson and Le 2011). The current participants had extensive and more proximal reinforcement histories with echoic prompts used to teach intraverbal behavior as this was the primary tactic used in their classrooms. However, the echoic condition was not consistently more efficient across participants, a finding that differs from that of previous researchers (Coon and Miguel 2012; Ingvarsson and Le 2011). It is likely that variables such as one’s existing repertoire and preferences may affect which modality is more efficient for a particular learner (Ingvarsson and Le 2011). For example, textual prompts may be more efficient for individuals like James who read and demonstrated a preference for textual stimuli. Individuals with stronger echoic repertoires like Anna may learn more quickly with echoic prompts. Anna’s results for Set 1 are noteworthy because she demonstrated the slowest transfer of stimulus control during the initial training. Ingvarsson and Le (2011) suggested that the benefits of one’s history might be most evident when the individual shows a slow initial transfer of control, as was the case for Anna. In contrast, James’s recent history with echoic prompts did not appear to benefit him during training on Set 1 as he did not meet the mastery criterion after 11 training sessions in the echoic condition but met it after six sessions in the textual condition. Despite Mike’s extensive history with echoic prompts, he learned equally as fast in the tact-prompt conditions. It is possible that James and Mike benefited from the prolonged exposure to the visual prompt (Finkel and Williams 2001; Vedora et al. 2009) or employed visual imaging strategies in the presence of tact or textual prompts (Ingvarsson and Hollobaugh 2011). Additional research is needed to determine factors beyond one’s learning history that impacts the efficiency of prompting tactics.

Individuals with autism are often considered visual learners and are thought to benefit more from the use of visual supports or prompts than auditory or echoic prompts (Quill 1997; West 2008). However, the present findings and the results of prior studies do not lend support to this notion and indicate that some individuals with autism may learn intraverbal responses more effectively and efficiently with echoic prompts rather than visual prompts. Given the complexity of stimulus control involved in establishing advanced intraverbal behavior (Sundberg and Sundberg 2011), practitioners might benefit from determining which prompting tactic is most efficient for an individual learner. In cases like Mike’s where there is not a superior prompting tactic, other variables such as ease of implementation, the individual’s existing repertoire and history with prompts, or the form of the response (e.g., it cannot be represented pictorially) might influence the selection of a prompting tactic (Ingvarsson and Le 2011).

There are several potential limitations to the present study. First, it is possible that the level of difficulty between questions and answers contributed to some of the differences in responding. Questions were assigned to sets based on the length of the question and response, but the equivalence of sets was not empirically demonstrated (Sindelar et al. 1985). Additionally, because there was only one unknown question trained, it is possible that participants’ intraverbal responses were not under the appropriate stimulus control and they responded via exclusion when presented with an unknown question. For example, when presented with an unknown question such as “What do you eat with?”, an individual may get reinforced for saying “fork.” In the absence of other unknown questions within a session the individual may have simply learned when presented with an unknown question, saying “fork” resulted in reinforcement. This concern is mitigated by the fact that the participants rarely emitted the previously reinforced response when conditions were switched. Future researchers should include at least two to three unknown targets within an instructional set. Finally, the follow-up probes were limited as the error correction and reinforcement procedures in place.

In summary, the current results were mixed and support the notion that the efficiency of prompting tactics used in intraverbal training is idiosyncratic across individuals (Ingvarsson and Le 2011). The present study extended the line of comparative research evaluating intraverbal prompting tactics to young adults with conditions that were better equated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fátima Diaz, Sarah Legoutte, Pam Marcotte, and Victoria Lucarini for their assistance with data collection.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Coon JT, Miguel CF. The role of increased exposure to transfer-of-stimulus control procedures on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:657–666. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel AS, Williams RL. A comparison of textual and echoic prompts on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior in a six-year-old boy with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2001;18:61–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03392971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson ET, Hollobaugh T. A comparison of prompting tactics to establish intraverbals in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:659–664. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson ET, Le DD. Further evaluation of prompting tactics for establishing intraverbal responding in children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:75–93. doi: 10.1007/BF03393093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Fuchtman R, Paden A. A comparison of intraverbal training procedures for children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:155–160. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quill KA. Instructional considerations for young children with autism: the rationale for visually cued instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1997;27:697–714. doi: 10.1023/A:1025806900162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar PT, Rosenberg MS, Wilson RJ. An adapted alternating treatments design for instructional research. Education and Treatment of Children. 1985;8:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML, Sundberg CA. Intraverbal behavior and verbal conditional discriminations in typically developing children and children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:23–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03393090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML, San Juan B, Dawdy M, Arguelles M. The acquisition of mands, tacts, and intraverbals by individuals with traumatic brain injury. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1990;8:83–99. doi: 10.1007/BF03392850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedora J, Meunier L, Mackay H. Teaching intraverbal behavior to children with autism: a comparison of textual and echoic prompts. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2009;25:79–86. doi: 10.1007/BF03393072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West EA. Effects of verbal cues versus pictorial cues on the transfer of stimulus control for children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2008;23:229–241. doi: 10.1177/1088357608324715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]