Abstract

Objectives

Racial disparities exist for multiple health outcomes and cognitive domains across the lifespan. Many physical health disparities appear less prominent in late life, which is likely due to higher mortality rates for African Americans. This study examined whether this attenuation of racial disparities at older ages observed for physical health outcomes can be extended to cognitive outcomes in mid-life and late-life samples. Evidence of selective survival with respect to cognition would imply that conventional risk factor patterns for dementia may be distorted among older African Americans, and clinical predictions based on less selected white peers will be inaccurate.

Design

Cross-sectional associations between race and cognitive functioning were examined as a function of age.

Setting

The National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) and the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP).

Participants

3,857 MIDUS participants (10.5% African American); 2,729 WHICAP participants (53.8% African American).

Measurements

Composite scores of executive functioning and episodic memory.

Results

Independent of main effects of age, birth cohort, sex, education and chronic health conditions, significant age by race interactions indicated that racial disparities in episodic memory and executive functioning were larger at younger ages than older ages in both samples.

Conclusion

Attenuation of racial inequalities at older ages can be extended to cognitive outcomes, which likely reflects selective survival. Research on cognitive disparities or on race-specific causes of cognitive outcomes in old age must incorporate corrections for selective survival if the goal is to identify causal predictors of cognitive outcomes, rather than merely statistical predictors.

Keywords: Race, African Americans, Cognition, Memory, Executive functioning

INTRODUCTION

Racial disparities exist for many health outcomes and multiple domains of cognition. Cognitive disparities are relevant to the study of dementia risk, which has been estimated to be twice as high among African Americans, compared with non-Hispanic Whites.[1] Previous work has described how the magnitude of health disparities appears to depend on the age of the population under study. Health disparities for many outcomes appear less prominent in late life, which likely reflects selective survival.[2-3] However, health disparities for other outcomes appear more prominent in late life or stable across the life course.[4] The current study sought to extend previous research on physical health outcomes to cognition. Investigating the magnitude of cognitive disparities in younger versus older people will advance understanding of specific biases in research on dementia risk. Evidence of selective survival with respect to cognition would imply that conventional risk factor patterns for dementia may be distorted among older African Americans, and clinical predictions based on less selected white peers will be inaccurate.

Older African Americans obtain lower scores on a wide range of cognitive assessments compared to non-Hispanics Whites.[5-7]. Educational factors that differ across racial groups may account for these differences. More and better education leads to greater learning opportunities throughout life, as well as higher literacy levels, income and occupational status, all of which may affect performance on neuropsychological testing.[8-9] The theory of cumulative advantage and disadvantage (CAD) posits that stress and resource limitations throughout different stages of life accumulate over time to produce worse health outcomes.[10-12] Thus, CAD theory would suggest that racial disparities in cognitive performance would increase or widen with age.

Racial disparities in physical health have been well-documented. For example, older African Americans have a higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension[13-14], and cardiovascular disease[15] than non-Hispanic Whites. However, there is evidence that the magnitude of these health disparities is smaller at older ages, which has been described as the age-as-leveler hypothesis.[2-3] Although the age-as-leveler hypothesis is often contrasted with CAD, Dupre (2007) demonstrated that for educational inequalities, selective survival processes could attenuate population-level disparities in old age, even as individual-level inequalities worsened.[16] With respect to racial disparities, higher mortality rates and a lower life expectancy for African Americans in early and mid-life[4] results in a smaller proportion of African Americans surviving to late life, compared to non-Hispanic Whites. By definition, the survivors exhibit a greater degree of hardiness (i.e., physical and/or mental resilience), which would lead to the observed narrowing of racial disparities at later ages.[17-18] If the course of cognitive aging mirrors other health conditions, the age-as-leveler hypothesis would suggest that racial inequalities in cognitive performance would also appear smaller among the oldest old.

The current study tested whether cognitive disparities were larger or smaller at later ages in two large cohort studies in the United States: the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) and the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP). Larger disparities at later ages would be consistent with CAD theory, while smaller disparities at later ages would be consistent with the age-as-leveler hypothesis. However, as discussed above, the age-as-leveler hypothesis and CAD theory are not mutually exclusive. The implications of this research question extend to any study that uses between-person contrasts to evaluate racial disparities or to seek the determinants of healthy cognitive aging across racial groups. Smaller cognitive disparities among older participants would suggest that selective survival is a major source of bias in studies determining racial patterns in cognitive aging.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Data for this cross-sectional study were drawn from the second wave (2004-2006) of the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS-II), including the Milwaukee oversample, and all three waves (1992, 1999, 2009) of the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project.

MIDUS is a national sample of non-institutionalized, English-speaking adults selected by random digit dialing.[19] The second wave of MIDUS (MIDUS-II) included a cognitive battery, as described below. Inclusion criteria for the current study were: (1) age 40 and over (range 40-83; median 57), (2) self-reported ethnicity of “non-Hispanic,” and (3) self-reported race of either “White” or “Black/African American” at the time of MIDUS-II. If data on racial/ethnic identity was not available for the MIDUS-II visit, participants’ responses were imputed from the first MIDUS visit. The final sample included 3,453 non-Hispanic Whites and 404 African Americans.

WHICAP is a community-based longitudinal study of aging and dementia in northern Manhattan.[1,20] Participants were recruited from Medicare lists in three waves beginning in 1992, 1999, or 2009. The current study only included data from participants’ baseline neuropsychological evaluation. Inclusion criteria for the current study were (1) age 65 and over (range 65-102; median 75), (2) self-reported ethnicity of “non-Hispanic,” (3) self-reported race of either “White” or “Black/African American,” and (4) no consensus diagnosis of dementia. The final sample included 1,260 non-Hispanic Whites and 1,469 African Americans.

Both MIDUS and WHICAP were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards, including informed consent. In addition, the current secondary data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University.

Cognitive Outcomes

Cognitive testing in MIDUS-II was carried out over the phone with the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT).[21-22] Previous factor analysis of the BTACT in MIDUS-II revealed that it comprises two factors reflecting episodic memory and executive functioning.[23] Cognitive testing in WHICAP was carried out in person with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery.[24] Because MIDUS-II featured a more limited neuropsychological battery than WHICAP, cognitive composites were derived from the WHICAP battery to best match those available from MIDUS-II. A complete list of tests included in the episodic memory and executive functioning composites used in this study is shown in Table 1. Composite scores were computed separately in MIDUS-II and WHICAP as mean z-scores within each domain.

Table 1.

Corresponding cognitive domains assessed in the MIDUS and WHICAP samples

| MIDUS | WHICAP |

|---|---|

| Episodic memory | |

| Word List Immediate | Word List Immediate |

| Word List Delayed | Word List Delayed |

|

Executive functioning | |

| Category Fluency | Category Fluency |

| Digits Backward | Letter Fluency |

| Number Series | Verbal Abstraction |

| Backward Counting | - |

| Stop & Go Switch Task | - |

MIDUS=National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States; WHICAP=Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project

Covariates

All analyses controlled for main effects of age, sex, race, education, and health (i.e., number of chronic conditions). In both studies, age was self-reported at the time of the cognitive assessment included in the current study. In MIDUS-II, self-reported education was quantified as a 12-category variable ranging from “no school/some grade school” to “PhD, EdD, MD, DDS, LLB, LLD, JD, or other professional degree.” In WHICAP, education was quantified as self-reported years of school (0-20). In MIDUS-II, health was quantified as the number of self-reported chronic conditions out of a list of 30 potential conditions. In WHICAP, health was quantified as the number of self-reported chronic conditions out of a list of 10 potential conditions. Because WHICAP participants included in this study were drawn from three recruitment waves, birth cohort was used as an additional covariate in WHICAP analyses. Birth cohort was a 5-category variable reflecting birth year: (0=lowest through 1909, 1=1910-1919, 2=1920-1929, 3=1930-1939, 4=1940-highest).

Statistical Analysis

Racial differences were evaluated separately in each sample using t-tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables. Separate linear regressions were used to estimate main effects of age and race, and their interaction (i.e., product term), to predict episodic memory and executive functioning composites in MIDUS-II and WHICAP. As defined above, all analyses controlled for sex, education, and health. WHICAP analyses additionally controlled for birth cohort. To provide an intuition for the impact of the linear interaction terms, we estimated main effects models stratified at the sample-specific medians (≥57 years for MIDUS and ≥75 years for WHICAP).

RESULTS

Racial Differences

Racial differences in MIDUS and WHICAP are shown in Table 2. Compared to non-Hispanic Whites in MIDUS, African Americans in MIDUS were older, comprised a greater proportion of women, were less likely to have attended college, reported more chronic health conditions, and scored lower on episodic memory and executive functioning composites. Compared to non-Hispanic Whites in WHICAP, African Americans in WHICAP comprised a greater proportion of women, attended fewer years of school, reported more chronic health conditions, and scored lower on episodic memory and executive functioning composites.

Table 2.

Characteristics of African American and non-Hispanic White sample members in MIDUS and WHICAP

| African American | Non-Hispanic White | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

MIDUS

| |||

| Age | 56.67 ± 10.61 | 58.05 ± 11.27 | .014 |

| Sex (% female) | 64.9 | 53.8 | <.001 |

| Education (% with any college) | 55.0 | 66.8 | <.001 |

| Chronic conditions | 3.53 ± 3.63 | 2.50 ± 2.47 | <.001 |

| Episodic memory | −0.36 ± 0.98 | 0.00 ± 0.99 | <.001 |

| Executive functioning | −0.82 ± 0.97 | 0.05 ± 0.96 | <.001 |

|

WHICAP | |||

| Age | 76.09 ± 6.55 | 76.23 ± 6.84 | .568 |

| Birth cohort | - | - | .067 |

| % lowest-1909 | 5.3 | 5.4 | - |

| % 1910-1919 | 24.5 | 21.9 | - |

| % 1920-1929 | 37.6 | 38.3 | - |

| % 1930-1939 | 20.2 | 18.7 | - |

| % 1940-highest | 12.3 | 15.8 | - |

| Sex (% female) | 70.6 | 61.5 | <.001 |

| Education (years) | 11.55 ± 3.71 | 13.78 ± 3.67 | <.001 |

| Chronic conditions | 2.30 ± 1.66 | 2.03 ± 1.56 | <.001 |

| Episodic memory | −0.20 ± 0.88 | 0.23 ± 0.95 | <.001 |

| Executive functioning | −0.28 ± 0.75 | 0.34 ± 0.84 | <.001 |

MIDUS=National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States; WHICAP=Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project

Race by Age Interactions

Results from linear regressions in MIDUS and WHICAP are shown in Table 3. In both samples, older age and African American race were each independently associated with poorer episodic memory and executive functioning. There were also significant age by race interactions for episodic memory and executive functioning in both samples, indicating that racial differences were attenuated in older individuals.

Table 3.

Predictors of cognition in linear models

| Episodic Memory | Executive Functioning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIDUS | Estimate (SE) | 95% CI | Estimate (SE) | 95% CI |

| Age | −0.037 (0.005) | −0.047, −0.027 | −0.040 (0.005) | −0.049, −0.031 |

| Female | 0.508 (0.031) | 0.447, 0.568 | −0.088 (0.027) | −0.141, −0.034 |

| African American | −0.998 (0.263) | −1.515, −0.481 | −1.283 (0.233) | −1.739, −0.827 |

| Education | 0.073 (0.006) | 0.061, 0.085 | 0.129 (0.005) | 0.119, 0.140 |

| Chronic conditions | −0.022 (0.006) | −0.033, −0.010 | −0.035 (0.005) | −0.045, −0.025 |

| Age by African American | 0.011 (0.005) | 0.002, 0.020 | 0.009 (0.004) | 0.001, 0.017 |

|

WHICAP | ||||

| Age | −0.060 (0.008) | −0.077, −0.044 | −0.030 (0.007) | −0.042, −0.017 |

| Female | 0.303 (0.034) | 0.237, 0.370 | −0.043 (0.027) | −0.095, 0.009 |

| African American | −1.323 (0.368) | −2.045, −0.602 | −1.453 (0.285) | −1.982, −0.857 |

| Education | 0.059 (0.005) | 0.050, 0.068 | 0.090 (0.004) | 0.082, 0.097 |

| Chronic conditions | −0.014 (0.011) | −0.035, 0.007 | −0.007 (0.009) | −0.024, 0.010 |

| Birth cohort | 0.052 (0.024) | 0.004, 0.099 | 0.193 (0.019) | 0.156, 0.231 |

| Age by African American | 0.013 (0.005) | 0.004, 0.022 | 0.013 (0.004) | 0.006, 0.021 |

MIDUS=National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States; WHICAP=Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project

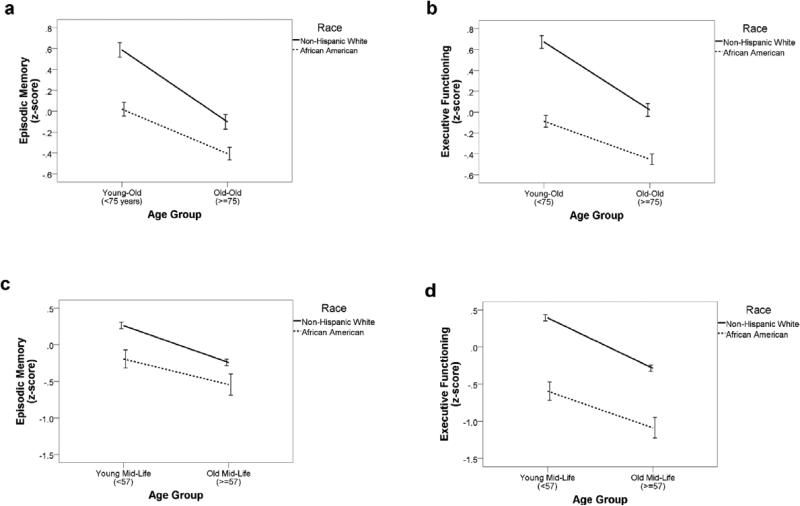

Next, linear regressions stratified by age group (split at sample-specific medians of ≥57 for MIDUS and ≥75 for WHICAP) were estimated. In MIDUS, the independent effect of race on episodic memory performance was stronger among younger participants (B=−0.420; 95% CI=−0.552 to −0.288; p<.001), compared to older participants (B=−0.333; 95% CI=−0.474 to −0.191; p<.001). Similarly, the independent effect of race on executive functioning performance was stronger among younger participants (B=−0.855; 95% CI=−0.972 to −0.739; p<.001), compared to older participants (B=−0.673; 95% CI=−0.799 to −0.547; p<.001) in MIDUS. In WHICAP, the independent effect of race on episodic memory performance was stronger among younger participants (B=−0.398; 95% CI=−0.495 to −0.301; p<.001), compared to older participants (B=−0.264; 95% CI=−0.355 to −0.174; p<.001). Similarly, the independent effect of race on executive functioning performance was stronger among younger participants (B=−0.463; 95% CI=−0.540 to −0.387; p<.001), compared to older participants (B=−0.324; 95% CI=−0.95 to −0.252; p<.001) in WHICAP. Race by age interactions are displayed visually in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cognitive composite scores plotted separately by cognitive domain and study: a) episodic memory in WHICAP; b) executive functioning in WHICAP; c) episodic memory in MIDUS; d) executive functioning in MIDUS. Errors bars reflect 95% confidence intervals. MIDUS=National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States; WHICAP=Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that the attenuation of racial inequalities at older ages can be extended to cognitive outcomes. Specifically, racial differences in episodic memory and executive functioning were present across age groups but were smaller among older people in two large cohort studies representing mid- and late-life. These findings were identified in the context of numerous racial differences in cognitive performance and demographics and were independent of birth cohort, sex, education, and burden of chronic health conditions. Results are in line with the age-as-leveler hypothesis,[3] which may occur if a relatively smaller, more resilient subset of African American individuals survive to late life, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.

The present finding of attenuated racial disparities at later ages differs from that of Obidi et al. (2008), who reported significant age by race interactions in their cross-sectional study of task-switching and processing speed.[25] Specifically, these authors found larger racial disparities among older men in a sample recruited from Veterans Administration Medical Centers. However, that study was conducted in a highly specific population of veterans diagnosed with diabetes and only included 25 African Americans. The age-as-leveler hypothesis would not necessarily be expected to apply in such a context, in which the healthiest older African Americans were likely to have been excluded from the study sample.

The present cross-sectional study is consistent with longitudinal studies showing reduced rates of cognitive decline among older African Americans, compared to older non-Hispanic Whites.[26-27] That is, if non-Hispanic Whites start out at a higher cognitive level but experience greater cognitive decline with age, then racial differences in cognitive performance in a longitudinal study would be expected to be smaller at each follow-up. Indeed, in an early longitudinal study in the WHICAP cohort, racial disparities in Alzheimer's disease incidence appeared to be largest among the youngest group of older adults.[1] In a cross-sectional study, reduced rates of cognitive decline among older African Americans would manifest as smaller racial differences among participants recruited at older ages. Reduced rates of cognitive decline among older African Americans may also reflect selective survival. However, it should be noted that other studies have reported accelerated rates of cognitive decline among older African Americans, compared to older non-Hispanic Whites.[28-30]. Thus, additional longitudinal research is needed to identify the sources of disparate findings across cohorts (e.g., statistical bias due to baseline adjustment).[31] A major limitation of this study is that it is cross-sectional. However, a longitudinal study comparing rates of cognitive decline between comparable samples of African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites (i.e., before the emergence of selective survival) would require extremely long follow-up.

Other limitations of this study include the disparate measures included in the executive functioning composites in MIDUS-II and WHICAP, as only one measure (category fluency) was common to both studies. However, the use of composites rather than individual tests lessens the impact of these differences, and the consistency of results across studies despite measurement differences increases confidence in the finding of attenuated racial disparities at older ages. Because unequal interval scaling of the cognitive measures could obscure the interpretation of our results, future studies should endeavor to include cognitive outcome measures calibrated across the entire range of ability using item response theory. It is possible that age-related racial differences in older adults’ decisions to participate in research studies cold confound our results. Specifically, it is possible that African Americans with cognitive difficulties are more likely than Whites to decline participation as they get older. Such an explanation would reflect underlying inequalities, consistent with the finding of greater functional impairment among African Americans compared with non-Hispanic Whites with similar chronic illness burden.[32, 4]. We have attempted to address this issue by coordinating analyses across two large cohort studies that differed in many ways, including age, recruitment methods, racial composition and geographical distribution.

Attenuation of social disparities at older ages is widely, although not universally, interpreted as indicating selective survival, such that the surviving members of the disadvantaged group are people with exceptional biological, environmental, psychological, or social profiles that provided resilience. Such selective survival has a very challenging implication for research on the determinants of healthy cognitive aging: any study that is based on between-person contrasts is likely biased. This would include, for example, studies based on prevalent or incident dementia or analyses that include between-person differences in estimating longitudinal changes. Many studies on differences in genetic causes of dementia between African Americans and whites would be vulnerable to such a bias. For example, if a gene is related to both mortality and dementia, and its association with mortality is stronger among African Americans, then its estimated effects on dementia among African Americans would be weaker. Indeed, multiple datasets have revealed weaker effects of APOE-ε4 on dementia among African Americans, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.[33-34] Our results strongly suggest that selective survival is a major force in determining racial patterns in cognitive aging. Research on disparities or on race-specific causes of cognitive outcomes in old age must incorporate corrections for such selective survival if the goal is to identify causal predictors of cognitive outcomes (which can be intervention targets), rather than merely statistical predictors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding Source: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (047963, 037212). This work was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR000040, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, grant number UL1 RR024156. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Sponsor's Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of this paper.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LBZ: concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. JJM: concept and design, acquisition of subjects and data, interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. MA: preparation of manuscript. MMG: interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tang M-X, Cross P, Andrews H, et al. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Seeman TE. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and health. In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Miech R. The black-white difference in age trajectories of functional health over the life course. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendes de Leon CF, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, et al. Racial disparities in disability: Recent evidence from self-reported and performance-based disability measures in a population-based study of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60B:263–271. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.s263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisco S, Gross AL, Shih RA, et al. The role of early-life educational quality and literacy in explaining racial disparities in cognition in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70B:557–567. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewster PWH, Marquine MJ, MacKay-Brandt A, et al. Life experience and demographic influences on cognitive function in older adults. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:846–858. doi: 10.1037/neu0000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz BS, Glass TA, Bolla KI, et al. Disparities in cognitive functioning by race/ethnicity in the Baltimore memory study. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:314–320. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, et al. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer's disease. JAMA. 1994;271:1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, et al. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and white elders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;8:341–348. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrd DA, Miller SW, Reilly J, et al. Early environmental factors, ethnicity, and adult cognitive test performance. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20:243–260. doi: 10.1080/13854040590947489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crystal S, Shea D. Cumulative advantage, cumulative disadvantage, and inequality among elderly people. Gerontologist. 1990;30:437–443. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Rand AM, Henretta JC. Age and Inequality: Diverse Pathways through Later Life. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pieterse AL, Carter RT. An explorators investigation of the relationship between racism, racial identity, perceptions of health, and health locus of control among black American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:334–348. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitson HE, Hastings SN, Landerman LR, et al. Black-white disparity in disability: The role of medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:844–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margellos H, Silva A, Whitman S. Comparison of health status indicators in Chicago: Are black-white disparities worsening? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1612–1617. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupre ME. Educational differences in age-related patterns of disease: Reconsidering the cumulative disadvantage and age-as-leveler hypotheses. J Health Soc Beh. 2007;48:1–15. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Chen JT. Methodological challenges in causal research on racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive trajectories: Measurement, selection, and bias. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18:194–213. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9066-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson NE. The racial crossover in comorbidity, disability, and mortality. Demography. 2000;37:267–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brim O, Ryff C, Kessler R. How Healthy Are We? A National Study of Well-Being at Midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manly JJ, Tang M-X, Schupf N, et al. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:494–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachman ME, Tun PA. Cognitive Testing in Large-scale Surveys. In: Hofer SM, Alwin DF, editors. Assessment by telephone. In: Handbook of Cognitive Aging: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. pp. 506–523. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tun PA, Lachman ME. Age differences in reaction time and attention in a national sample of adults: Education, sex, and task complexity matter. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:1421–1429. doi: 10.1037/a0012845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachman ME, Agrigoroaei S, Murphy C, et al. Frequent cognitive activity compensates for education differences in episodic memory. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:4–10. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ab8b62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern Y, Andrews H, Pittman J, et al. Diagnosis of dementia in a heterogeneous population. Development of a neuropsychological paradigm-based diagnosis of dementia and quantified correction for the effects of education. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530290035009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obidi CS, Pugeda JP, Fan X, et al. Race moderates age-related cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes. Exp Agin Res. 2008;34:114–125. doi: 10.1080/03610730701876938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Early DR, Widaman KF, Harvey D, et al. Demographic predictors of cognitive change in ethnically diverse older persons. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:633–645. doi: 10.1037/a0031645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Li Y, et al. Change in cognitive function in Alzheimer's disease in African American and white persons. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:16–22. doi: 10.1159/000089231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HB, Richardson AK, Black BS, et al. Race and cognitive decline among community-dwelling elders with mild cognitive impairment: Findings from the memory and medical care study. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16:372–377. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.609533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer DG. Racial differences in cognitive decline in a sample of community-dwelling older adults: The mediating role of education and literacy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:968–975. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawyer K, Sachs-Ericsson N, Preacher KJ, et al. Racial differences in the influence of the APOE epsilon 4 allele on cognitive decline in a sample of community-dwelling older adults. Gerontology. 2009;55:32–40. doi: 10.1159/000137666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, et al. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:267–278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostchega Y, Harris TB, Hirsch R, et al. The prevalence of functional limitations and disability in older persons in the U.S.: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1132–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marden JR, Walter S, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, et al. Validation of a polygenic risk score for dementia in black and white individuals. Brain Beh. 2014;4:687–697. doi: 10.1002/brb3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan M-X, Stern Y, Marder K, et al. The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA. 1998;279:751–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]