Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

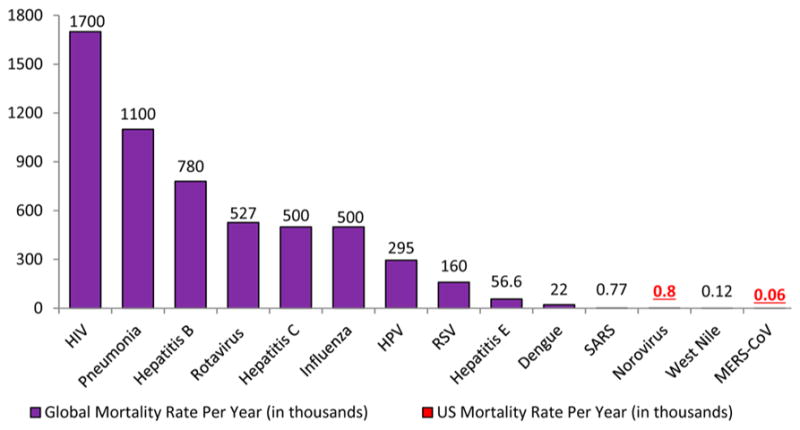

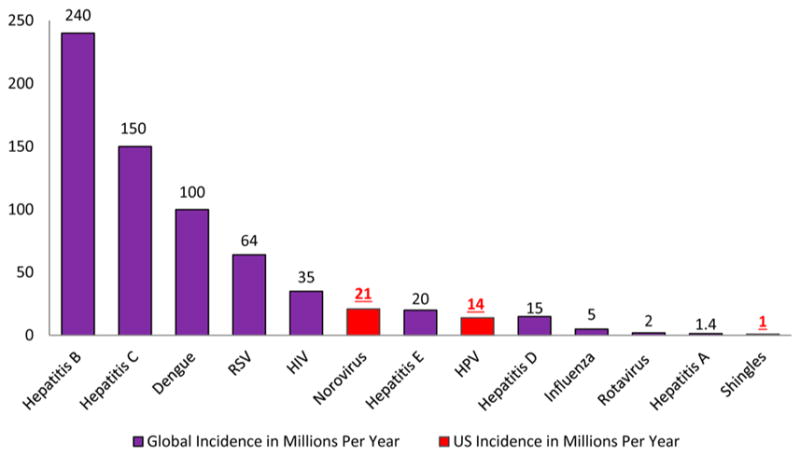

Mammals have complex biological systems and are constantly prone to infections by a wide array of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites, a significant challenge to the constant development of disease-strains resistance to current drugs.1 As a result, there is always a need to identify new anti-infective agents against these organisms. An anti-infective agent is defined by Webster as “an agent capable of acting against an infection, by inhibiting the spread of an infectious agent or by killing the infectious agent outright”.2 Some of the emerging and drug-resistant infectious diseases having research priority are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or AIDS, hepatitis B and C viruses, respiratory infections such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and dengue fever.1 Figures 1 and 2 provide us with the data in regards to the mortality and incidence rates, respectively, of people with viral diseases.3–5

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Search engines utilized to identify the literature reviewed here include Google scholar, Scifinder, Pubmed, government documents from the CDC, NIH, and the World Health Organization (WHO), academic journals, and books.

2. HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS DEMOGRAPHICS

HIV-1 and HIV-2 can infect humans and cause severe immunosuppression through depletion of CD4+ cells. HIV-2 was first isolated in West Africa in 1986, and its mode of transmission is similar to HIV-1 except that it is generally less infectious and the disease develops more slowly and is milder. As the disease progresses, there are more infections with shorter durations compared to that of HIV-1. HIV-2 is seen predominately in Africa, but increasing incidences have been documented in the United States since 1987.6

HIV and the resulting AIDS-associated infections have become an international epidemic,7 resulting in over 30 million AIDS-related deaths worldwide.8 In 2011, around 2.5 million people were diagnosed with HIV, and an estimated 1.7 million men, women, and children died from the complications of AIDS. Around 34 million people were living with HIV by the end of 2011, with 69% of those infected in Sub-Saharan Africa. Following Sub-Saharan Africa, the regions most affected with HIV are the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, where 1% of infected adults were living in 2011.7

In Asia, it is estimated that at least 4.8 million people are currently living with HIV, with China accounting for 780 000 of those infected individuals followed by Thailand and Indonesia. Eastern Europe and Latin America each has around 1.4 million infected people.9

In the United States, more than half a million people have died from AIDS-related complications,10 and it has been estimated that over 1.3 million people are infected with HIV,7 some of whom may not even be aware of their infection status.11 Those at greatest risk for infection include individuals engaged in high-risk behaviors, such as intravenous (IV) drug use.12 During 2007, in the United States, HIV was the fourth leading cause of death for Latinos and Hispanics between the ages of 35–44 and the sixth leading cause of death between the ages of 25–34.13 According to the National HIV/AIDS strategy,14 HIV and AIDS are most commonly seen among African Americans. AIDS was first documented by the United States CDC in 1982, in two females, one Latina and the other African American. The epidemic of AIDS began to spread among the African American population from this point forward.15

2.1. Nomenclature of HIV/AIDS

The first instances of AIDS can be traced back to 1981,6 when a strange illness began occurring in the homosexual communities; however, the pandemic is reported to have started in the late 1970s16 originating in Africa. In 1982, AIDS had different names that included gay cancer, gay-related immune deficiency (GRID),17 gay compromise syndrome,18 and community-acquired immune dysfunction. The term AIDS derived its acronym in July 1982, at a meeting in Washington, DC.19 Initially it was thought to be the disease of the “four H club” that included heroin addicts, hemophiliacs, homosexuals, and Haitians.16

The virus that was known to cause AIDS was initially named as lymphadenopathy-associated virus, or LAV, in May 1983.16 On April 23, it was announced that the virus known to cause AIDS was isolated and was named Human T-cell Leukemia Virus-III (HTLV-III). It was thought that the LAV and HTLV-III could be the same virus.20 In March 1985, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed the first blood test for AIDS21 created by Abbott Laboratories to identify possible antibodies (for HIV).22 The name HIV or Human Immunodeficiency Virus was given by the International Commission on Virological Nomenclature in May 1986.16

2.2. Emergence of Drugs From Marine Sources

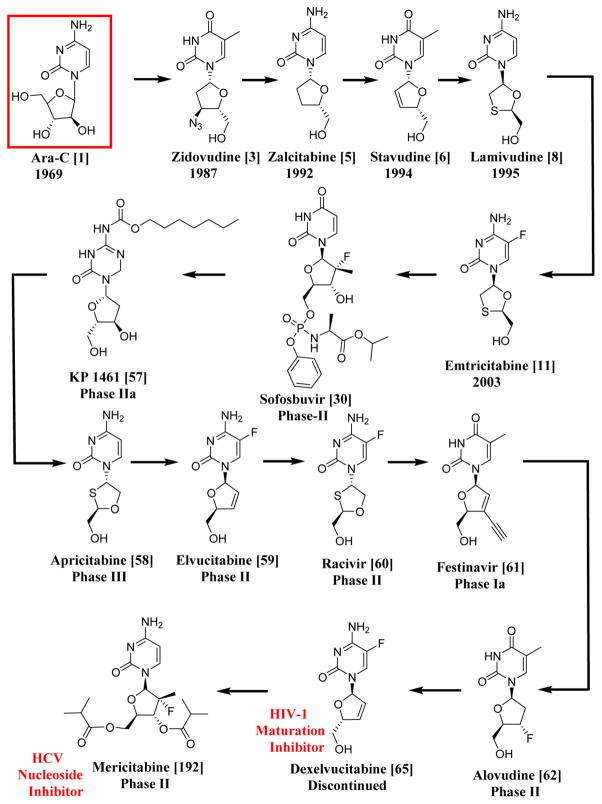

Nature plays an important role in the generation of unique drug prototypes of which about 60% of anticancer agents are derived from natural sources and around 95% of the earth’s biosphere are represented by the marine ecosystem.23 Hence, marine sources can be an invaluable source for the discovery of new compounds for the treatment of diseases like AIDS or cancer. As an example, three compounds, spongosine, spongothymidine,24 and spongouridine,25 were isolated from Cryptotethia crypta, a Caribbean marine sponge. These compounds were some of the first reported bioactive nucleosides isolated from a marine species. The first anticancer lead from marine organisms was cytosine arabinoside or ara-C (1), a synthetic derivative developed from a sponge natural product prototype.25 The syntheses of ara-C were first reported by Walwick in 1959, and Lee first reported the syntheses for ara-A (vidarabine) (2) in 1960.26 Ara-A was used as an antiviral agent for the treatment of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 infections for many years, although acyclovir (83) is more widely prescribed. Ara-C is used for the treatment of acute myelocytic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.26 The above mentioned drugs are the first FDA-approved marine-derived products used for the treatment of disease. They were also the basis for the synthesis and development of zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine, AZT or ZDV) (3), which was initially tested for cancer as an antibacterial but was later approved for HIV. Since then, extensive investigations have taken place for the treatment of various diseases from marine sources as well as for the further development of nucleosides (Schemes 1 and 2).

Scheme 1.

Systematic Representation of the Chronological Order of HIV-1 and HCV Drugs Having Similar Structures to Ara-C, the First Anticancer Lead from a Sponge; All the Drugs and Compounds Mentioned in This Scheme Are NRTIs except for Dexelvucitabine (65), Which Is an HIV-1 Maturation Inhibitor, and Mericitabine (192), Which Is an HCV Nucleoside Inhibitor

Scheme 2.

Systematic Representation of the Chronological Order of HIV-1 and HCV Drugs Having Similar Nuclei to Ara-A, an Antiviral Agent; All the Drugs and Compounds Mentioned in This Scheme Are NRTIs

2.3. History of AIDS/HIV

Jerome Horwitz synthesized AZT (3) in 1964 as an anticancer drug.16 Samuel Broder and Hiroaki Mitsuya, who were investigators at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), determined its potent anti-HIV activity in February 1985, which led to its clinical development. In 1974, it was shown to inhibit the Friend leukemia virus (murine leukemia virus) replication,27 and in 1986, the clinical trials were conducted on HIV-infected persons.16 The drug was first approved by the FDA in March 198721 under the commercial name Retrovir.16 AZT (3) in its triphosphate form inhibits HIV reverse transcriptase, thereby blocking the expression of p24 gag protein of the virus.28 AZT (3) was the first drug to be used in the treatment of AIDS,21 and the first AIDS campaign coordinated by the nation was launched in 1988.29

In October 1991, FDA approved didanosine or 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (4).30 In June 1992, zalcitabine, also known as 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine (ddC) (5), a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), was approved by the FDA;8 it was mainly used in patients who were resistant to AZT.31 During the same year, a combination therapy was developed that became successful in utilizing both AZT (3) and ddC (5).32 In 1993, many cases occurred where people were resistant to AZT (3),33 and in June 1994 the FDA approved another NRTI, stavudine (6).8,34 It was also shown that the transmission of HIV from mother to child could be reduced by up to 66% with the use of AZT (3) during pregnancy.35 A recent example corresponding to this includes the antiretroviral therapy (ART) given 30 h after birth to an infant born with HIV-1 infection. ART was continued with detection of HIV-1 DNA and RNA; after the discontinuation of the therapy when the child reached 18 months of age, the child was found with undetectable HIV-1 antibodies, suggesting that early ART may help alter the long-term persistence of HIV-1 infection.36 However, the child was later found viral positive after two years off ART, suggesting continued challenges in controlling HIV infection.37

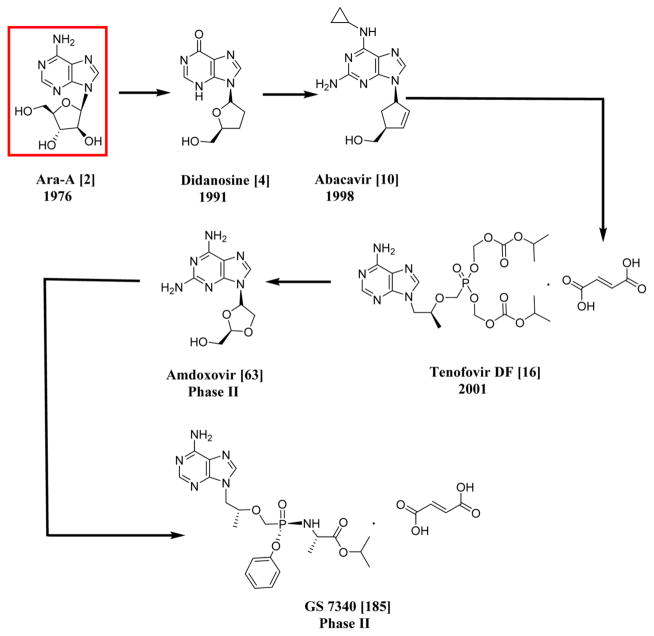

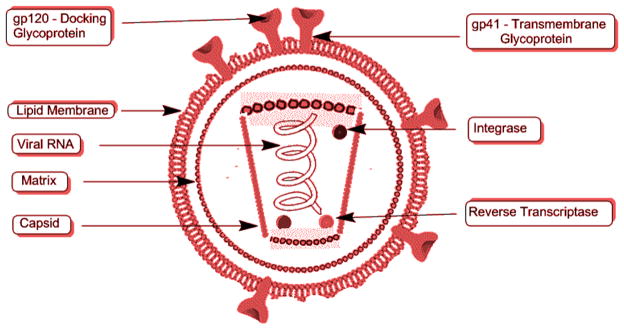

In 1995 the protease inhibitor saquinavir (invirase) (7) was approved by the FDA,38 and during the same year in November, the FDA approved the NRTI lamivudine or 3TC (8).39 In 1996 a new non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) viramune, also known as nevirapine (9), was approved by the FDA,40 and in the same year, the viral load test called Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test was introduced. This test gave clinicians the ability to document the progression of the disease.41 In September 1997, the FDA approved an NRTI combivir, which is a combination of lamivudine (8) and zidovudine (3).39 In 1998, two clinical trials proved that the combination of AZT (3) with ddC (5) was much more effective in prolonging life and delaying the disease compared to AZT (3) used alone.42 Abacavir (10),43 another NRTI, was approved by the FDA in December of the same year.8 In 1999, the original source of HIV was found to be from Pan troglodytes, a type of chimpanzee common in West Central Africa. It is hypothesized that the virus entered the human population when hunters were exposed to the infected blood of the chimpanzee.44

Nonoxynol-9, a spermicide, was proven to be an ineffective microbicide in the reduction of transmission of HIV during sex.45 The first HIV vaccine trial took place in Oxford, U.K., in September of 2000.46 In 2001 an Indian company, Cipla, offered AIDS drugs for as low as $1 per day,47 and in 2002 WHO provided guidelines for antiretroviral drugs and also released a list of 12 drugs that could be used for AIDS.48 T-20 (Fuzeon) (15), a fusion inhibitor, also came into existence as an injectable drug,49 bringing forth a new campaign for the control of the spread of HIV that was called ABC, short for “Abstinence, Being faithful, and Condom use”.50

A great mission of rescue was initiated by the former United States president George W. Bush in 2003 to combat AIDS in the Caribbean and in Africa.51 In the same year, Vaxgen made an announcement regarding the failure of the AIDS vaccine to reduce the HIV infection rate,52 and in November the vaccine was found to be a failure in a clinical trial in Thailand.53 On March 15, 2003, the FDA approved a new type of anti-HIV drug for the prevention of HIV entry into human cells. Fuzeon, also known as enfuvirtide or T-20 (15), was the first drug to be classified as a “fusion inhibitor”. Fuzeon was available in the form of an injection, and it could be used as combination therapy in patients resistant to other antiretroviral drugs.54 The unnatural L-nucleosides, lamivudine (8) and emtricitabine (11), became commercially available, and they revolutionized the treatment of HIV (and hepatitis B virus (HBV)), since these drugs are now part of many highly effective fixed-dose combinations.55 In July 2003, the FDA approved emtricitabine (11),8,56 and on December 1, 2003, World AIDS Day, the WHO declared a “three by five” campaign of providing antiretroviral treatment to three million people in resource-poor countries by 2005.57 Another similar policy called the “Four Free and One Care” was declared by the Chinese government that included many services such as providing free antiretroviral agents to the poor and rural communities, free testing and counseling, free drugs for the prevention of the transmission from mother to child, free schools for orphans of AIDS-related deaths, and proper care and economic help for people afflicted with HIV or AIDS.58

In 2004, for the first time in their history, the Global Fund stopped the funding scheme to fight AIDS.59 In March, the first oral fluid rapid test for HIV was approved by the United States FDA,60 and President George W. Bush’s PEPFAR, also known as the “President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief” was fully implemented in June 2004. This was designed to focus on 15 countries in Africa as well as Haiti, Guyana, and Vietnam.61

In January 2005, the FDA approved an antiretroviral agent co-packaged drug regimen (lamivudine (8)/zidovudine (3) and nevirapine (9)) made by Aspen Pharmacare, a South African company. This marked the first HIV drug regimen to be approved by a non-United States based pharmaceutical company, a milestone that represented a huge turning point in Africa for providing cheaper pharmaceutical treatments for HIV-1.62 In September 2005, the patent period for AZT came to an end, allowing many pharmaceutical companies to produce the drug and sell it at greatly reduced prices.62 In 2006, for the first time, a pill that could be taken only once a day for the treatment of HIV-1 infection was approved in United States. Now widely used in first-line treatment, Atripla included a combination of three drugs: Emtriva (emtricitabine (11)), Sustiva (efavirenz (19)), and Viread (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or TDF-(16)).63–65

In 2007, the FDA approved two new drugs, raltegravir (Isentress) (12)66 and maraviroc (Selzentry) (13),67 that could be used in patients resistant to all other classes of anti-HIV drugs. In October the initial results of a vaccine being developed by Merck pharmaceutical company were found to be ineffective, resulting in terminating the trial being conducted on hundreds of participants.68 In 2008, the American funding program PEPFAR was renewed for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis for the years 2009–2013.69

In 2009 President Obama promised to lift the travel ban that had been implemented for 22 years that prevented people infected with HIV/AIDS from entering the United States,70 and finally on January 2010 the ban was lifted.71 The results from a microbicide trial CAPRISA 004 highlighted the biannual International AIDS Conference in July 2010. According to Phase IIb trial results, it was found to be safe and effective to use an antiretroviral-based gel on HIV-negative women that reduced the risk of acquiring the infection by 40%.72 In October 2011, a new drug application for a single-drug regimen also known as the “QUAD” pill was submitted by Gilead Sciences, Inc., and this included elvitegravir (53), cobicistat (14), emtricitabine (11), and TDF (16).73 Truvada, a fixed-dose combination of emtricitabine (11) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (16), was approved by the FDA in July 2012 for the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV and was manufactured by Gilead.74 Dolutegravir (54) or Tivicay was approved by the FDA in August 2013 and was marketed by ViiV Healthcare and manufactured by GSK for use in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients.75 The history of HIV/AIDS is outlined from its conception until 2014, and all of the HIV/AIDS drugs that are currently available in the market can only be used to prevent further replication of the virus in the body and to extend the lifetime of people who are HIV-positive by a few more years. A cure to eradicate or eliminate HIV completely has yet to be identified (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Anti-HIV-1 drugs referenced in the history. Compounds include saquinavir (7),410 nevirapine (9),410 raltegravir (12), maraviroc (13), cobicistat (14),411 and fuzeon (15).412

2.4. Description of the Virus

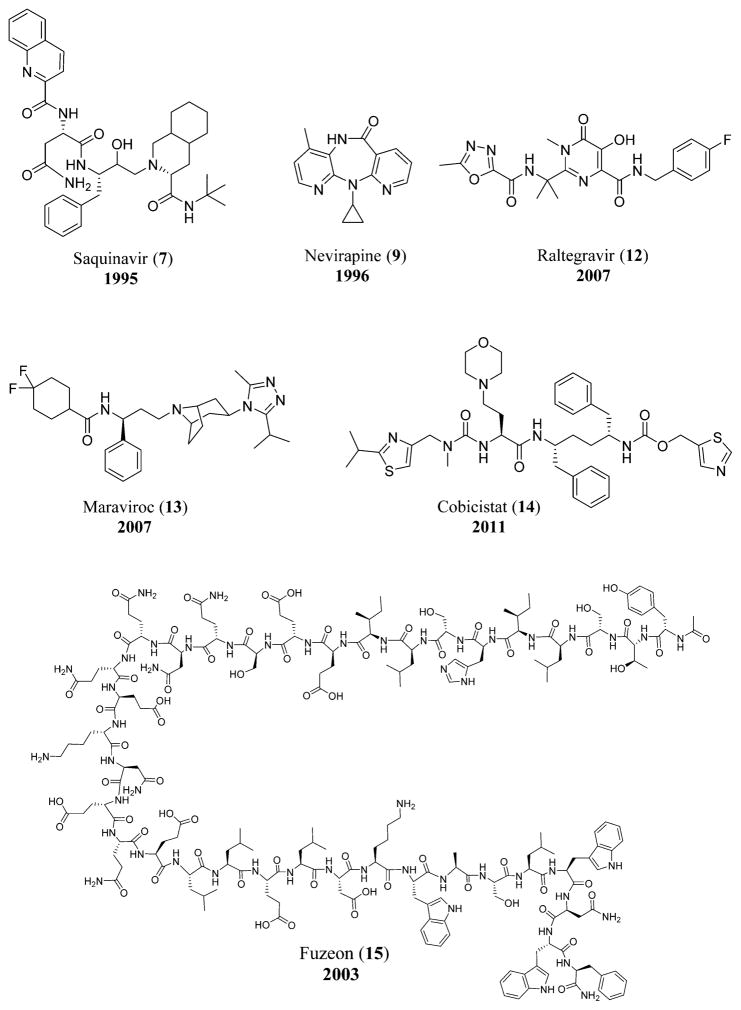

The virus particles are spherical with a diameter of one ten-thousandth of a millimeter. The viral envelope, which is the outer coat, includes two layers of lipids that are taken from the human membrane by the virus when a new virus is formed from the cell. Throughout the viral envelope, proteins including 72 copies of complex HIV-1 protein called env are embedded. The surface of the virus is spiked with these env copies and is called a “virion”. env includes glycoprotein 120 (gp120), which is a cap containing three molecules, and glycoprotein 41 (gp41), which is a stem with three molecules. These two proteins adhere to the structure of the viral envelope, and research concerning an HIV vaccine is mainly focused on these proteins.76

A bullet-shaped capsid or core is present inside the viral envelope that is made of ~2000 copies of p24, the viral protein. Surrounding the capsid are two single-stranded HIV-1 RNA, each including a complete copy of the viral genes. Gag, pol, and env are the three structural genes that carry information necessary for the formation of structural proteins for new viral particles. Similarly tat, nef, vif, vpr, vpu, and rev are the six regulatory genes responsible for the control of the virus in regards to infecting the host and producing the disease. An RNA sequence called the long terminal repeat (LTR) is present at the end of each strand of the viral RNA. These regions control the production of the new viruses. The nucleocapsid protein p7 is present in the core, and the matrix protein p17 is present between the core and the envelope. The virus also requires three enzymes for the completion of its replication cycle: reverse transcriptase, protease, and integrase (Figure 4).76

Figure 4.

Structure of HIV.

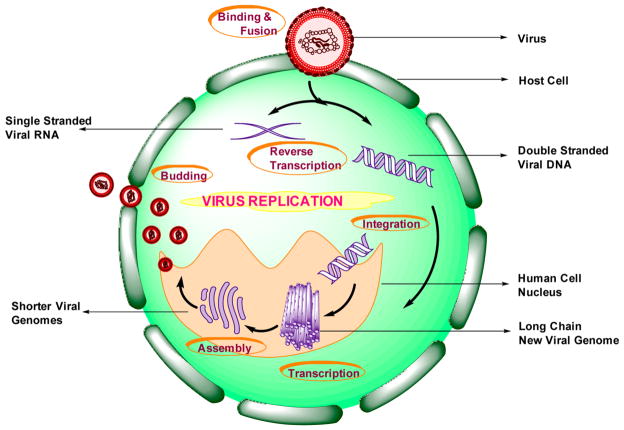

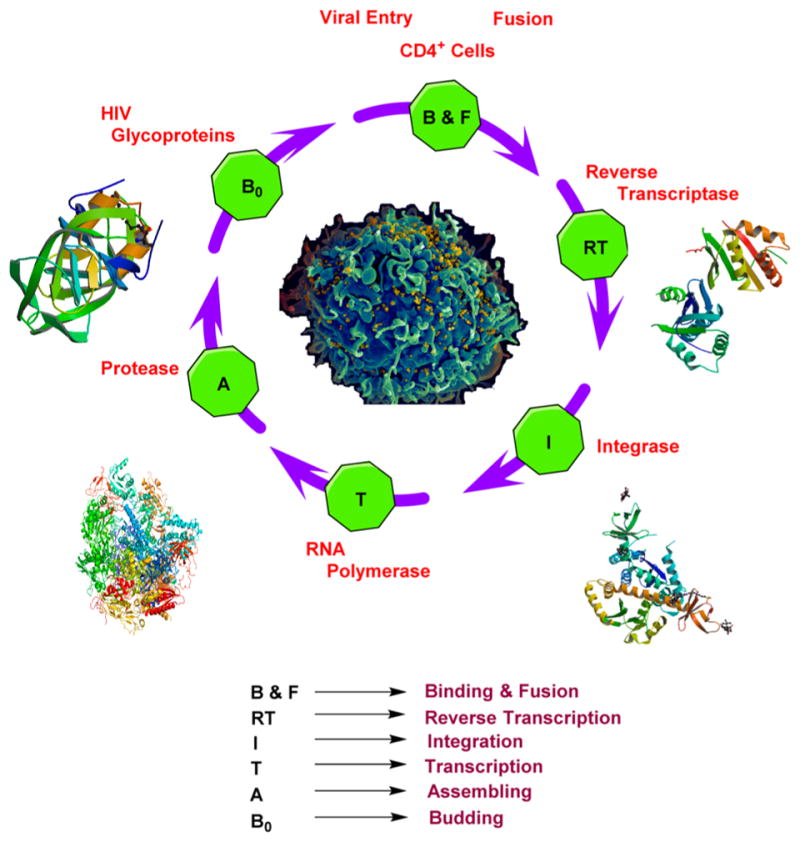

2.5. Virus Replication Cycle

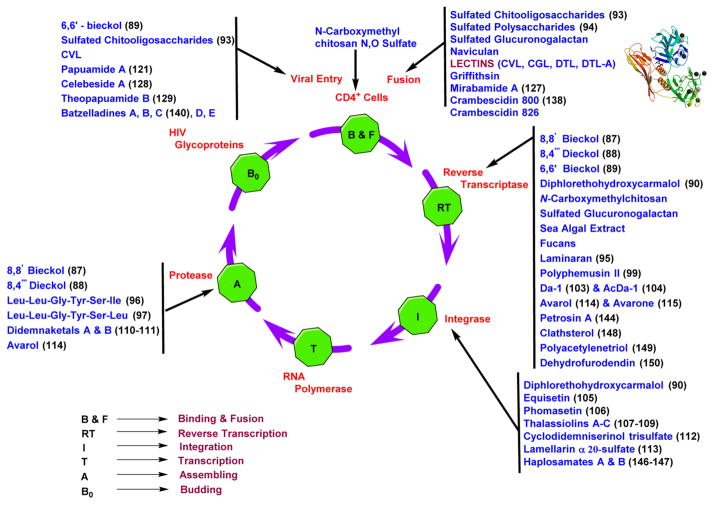

HIV can only reproduce in humans, and its replication cycle occurs in six stages, beginning with its binding to a CD4 receptor along with one of the co-receptors (among the two) on the CD4+ T-lymphocyte surface. This leads to the fusion of the virus (HIV-1) to the host cell, thereby leading to the release of viral RNA into the cell. This is called the Binding and Fusion stage. In stage II, called the Reverse Transcription stage, the reverse transcriptase enzyme present in the virus (HIV-1) converts single-stranded viral RNA to double-stranded viral DNA. Stage III is the Integration stage, where the viral DNA formed in stage II enters into the host cell nucleus and incorporates the viral DNA within the host cell’s own DNA by the viral enzyme integrase. This integrated viral DNA is called a provirus and could reproduce few or no copies or remain inactive for many years.

The fourth stage, Transcription, is where the provirus produces copies of the viral genome as well as messenger RNA or mRNA (shorter strands of RNA) with the help of the host’s RNA polymerase enzymes. This occurs whenever a signal is sent to the host cell to become active. The mRNA produced above is used to further produce long chains of viral proteins. Assembly is the fifth stage, where the long chains are cut into shorter individual proteins by the viral enzyme protease. These proteins along with the copies of viral RNA form a new virus particle. The sixth and the final stage is Budding. The above assembled virus buds out of the host cell. During this stage, the virus takes some of the cell’s outer membrane that contains sugar or protein combinations called HIV glycoproteins. These are required by the virus in order to bind with the CD4 and the co-receptors. After this is complete, these copies are now ready to infect new cells (Figures 5 and 6).77

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the virus replication cycle.

Figure 6.

Crystal structures of HIV reverse transcriptase,413 integrase,414 RNA polymerase,415 and protease416 and scanning electron micrograph of HIV.417 Courtesy: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, http://www.nih.gov/science/hiv/.

2.6. HIV–HCV Coinfection

HIV coinfection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is common due to the shared routes of transmission,78 and it is known to affect about one-third of all the people infected with HIV worldwide. The prevalence can vary depending on the factors of transmission.79 In the United States, approximately 25% of people infected with HIV are also infected with HCV. The statistics greatly increase for those that have additional risk factors such as intravenous drug use.80

HIV–HCV coinfection leads to higher concentrations of HCV RNA, thereby increasing the risk of cirrhosis by accelerating the progress of HCV-related liver disease. In HIV-infected persons, the natural progression of HCV is drastically increased as a result of the HCV infection simulating opportunistic diseases.81 Transmission by sexual or vertical factors is more important in cases of HIV than HCV, but coinfection of HIV–HCV increases the risk of both vertical and sexual transmission of HCV.82 As the infection of HIV progresses, it leads to a decrease in cell-mediated immunity that further enhances HCV replication, leading to an increase in infection rate and hepatocyte injury. The immune cells cannot respond to HCV in coinfected persons because they are impaired.83 High CD4 cell counts can result in significant fibrotic progression in coinfected patients.84 HIV–HCV coinfection also leads to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is known to have a higher incidence compared to those infected with HCV alone.85

Along with liver problems, HIV–HCV coinfected people exhibit symptoms of kidney disease and have a bleaker renal prognosis.86,87 There is an increased risk of significant kidney function deterioration in HIV–HCV coinfected women.88 Other coinfected persons developed membranous nephropathy, immunotactoid glomerulopathy, mesangial proliferative glomer-ulonephritis, and immune-deposited collapsing glomerulopathy.89 In summary, these coinfections lead to complicated diagnoses, clinical progression of the disease, monitoring, treatment, and the basic immunology.78

The treatment for the coinfection of HIV–HCV usually includes dual combination therapy of interferon (IFN)–ribavirin (RBV) and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). However, the coinfection increases the complexity of the treatment. Problems arise with the safety and efficacy of the drugs in these individuals.90 There are viral genome replication inhibitors that are used for the treatment of HIV–HCV coinfection.

The clinical symptoms and pathogenesis of HIV and HCV are similar. The polymerases of HIV include RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, also known as reverse transcriptase, and that of HCV includes RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, referred to as RNA replicase. Whereas HIV protease is an aspartyl protease, HCV’s protease is a serine protease. Some of the drugs belonging to different categories used in the treatment of HIV and HCV are mentioned below.

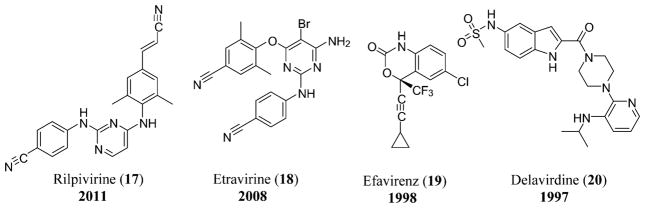

As of 2015, the only nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NtRTI) approved for the treatment of HIV is TDF or Viread (16), although all the currently approved nucleoside analogues require phosphorylation for inhibition of HIV polymerase.91 The non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) used in the treatment of HIV include nevirapine (9), rilpivirine or edurant (17), etravirine (18),8 efavirenz (19), and delavirdine (20) (Figure 7).92

Figure 7.

NNRTIs used for the treatment of HIV that include rilpivirine (17),410 etravirine (18),410 efavirenz (19),410 and delavirdine (20).410

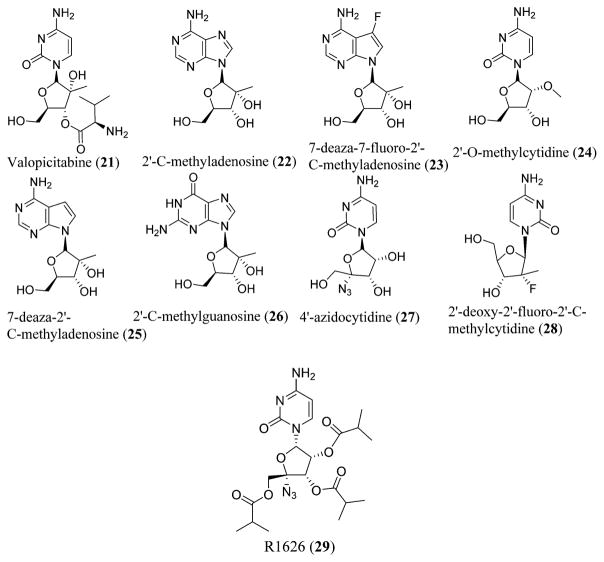

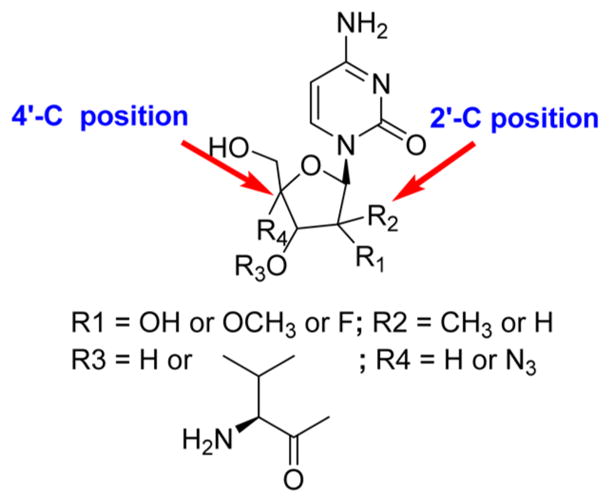

The known nucleoside RNA replicase inhibitors (NRRIs) possessing anti-HCV activity in vitro known to date include valopicitabine (21),93 2′-C-methyladenosine (22),94,95 7-deaza-7-fluoro-2′-C-methyladenosine (23),94,96 2′-O-methylcytidine (24),94 7-deaza-2′-C-methyladenosine (25),97 2′-C-methylguanosine (26),98,99 4′-azidocytidine (27),100 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine (28),101 oral prodrugs like R1626 (29),102,103 and novel analogues of 4′-azido-2′-deoxynucleoside (Figure 8).104

Figure 8.

Various NRRIs possessing anti-HCV activity. NRRIs include valopicitabine (21), 2′-C-methyladenosine (22), 7-deaza-7-fluoro-2′-C-methyladenosine (23), 2′-O-methylcytidine (24), 7-deaza-2′-C-methyladenosine (25), 2′-C-methylguanosine (26), 4′-azidocytidine (27), 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine (28), and R1626 (29).

To possess anti-HCV activity, the presence of a methyl group or a fluorine group at the 2′-C position or an azido group at the 4′-C position is essential. Any new nucleoside derivatives containing both substitutions in a single molecule would be an area of exploration for anti-HCV activity (Figure 9).92

Figure 9.

Structure–activity relationship (SAR) of anti-HCV NRRIs.

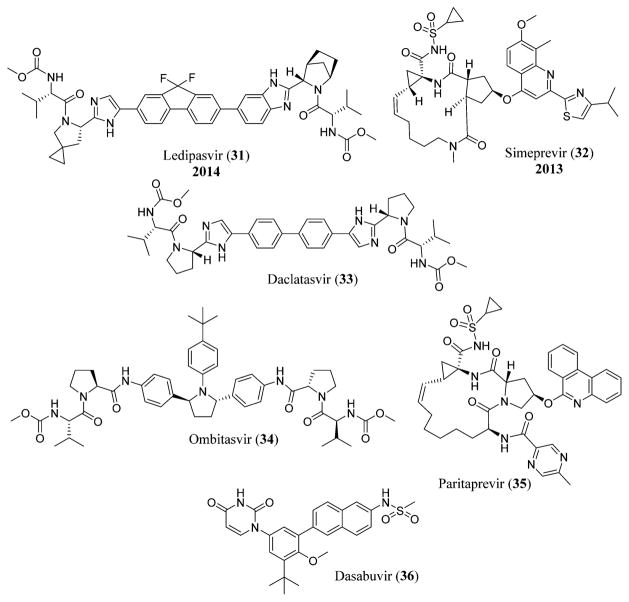

Sofosbuvir or GS-7977 (30), previously named as PSI-7977,105 is a uridine nucleotide analogue currently in Phase 2 trial for the treatment of HCV infection.106 It is a selective inhibitor of HCV NS5B polymerase. Combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin is also being tried for the efficacy of sofosbuvir (30) in treating HCV,107 although interferon-free treatments are now more popular (e.g., the use of sofosbuvir (30) with the NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir (31), a combination called Harvoni that has been approved by the FDA in October 2014).108 Simeprevir (32), a second-generation macrocyclic compound, is a NS3/4A HCV protease inhibitor that binds non-covalently to the HCV protease and was approved by the FDA in November 2013.109 Daclatasvir (33), a NS5A replication complex inhibitor manufactured by Bristol-Myers Squibb, was in Phase III clinical trials in combination with sofosbuvir (30) for the treatment of HCV,110 and its use in combination with other antiviral drugs for the treatment of HCV was declined by the FDA in November 2014.111 The FDA approved Viekira Pak in December 2014, which is a combination of ombitasvir (34), paritaprevir (ABT-450) (35), and ritonavir (46) tablets that are co-packed with dasabuvir (36) tablets for the treatment of chronic HCV infection (Figure 10).112

Figure 10.

Structures of ledipasvir (31),418 simeprevir (32),419 daclatasvir (33),418 ombitasvir (34),420 paritaprevir (35),421 and dasabuvir (36).422

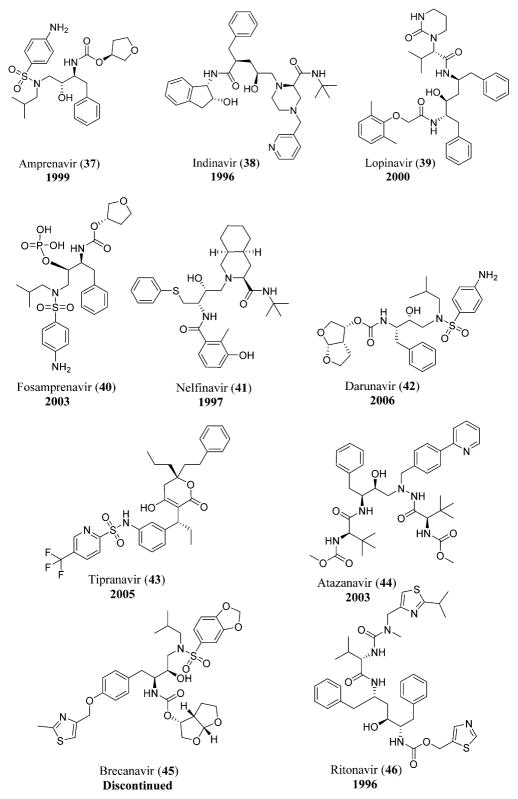

The proteases of HIV and HCV are attractive drug targets. The viral protease inhibitors used for the treatment of HIV include amprenavir (37), indinavir (38), lopinavir (39), fosamprenavir (40), nelfinavir (41),8 darunavir (42), tipranavir (43), and atazanavir (44).92 Another protease inhibitor, brecanavir (45), could be used in combination with ritonavir (46) for the treatment of HIV-1-infected persons (Figure 11).113,114

Figure 11.

HIV protease inhibitors including amprenavir (37),410 indinavir (38),410 lopinavir (39),410 fosamprenavir (40),410 nelfinavir (41),410 darunavir (42),423 tipranavir (43),410 atazanavir (44),410 brecanavir (45),424 and ritonavir (46).410

The HCV serine protease inhibitors include boceprevir (47),115 telaprevir (48),116 ciluprevir (49),117 and SCH446211 (50) (Figure 12A).118

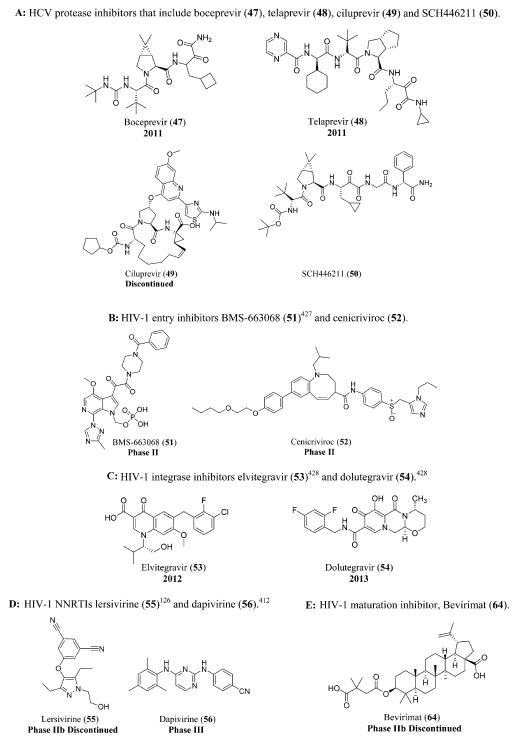

Figure 12.

(A) HCV protease inhibitors that include boceprevir (47), telaprevir (48), ciluprevir (49), and SCH446211 (50). (B) HIV-1 entry inhibitors BMS-663068 (51)425 and cenicriviroc (52). (C) HIV-1 integrase inhibitors elvitegravir (53)426 and dolutegravir (54). (D) HIV-1 NNRTIs lersivirine (55)126 and dapivirine (56).410 (E) HIV-1 maturation inhibitor, Bevirimat (64).

Other anti-HIV-1 drugs that are still in clinical trials include entry inhibitors such as PRO 140,119 TNX-355 or ibalizumab,120 BMS-663068 (51)121 and cenicriviroc (52),122 integrase inhibitors such as elvitegravir (53)123 and dolutegravir (54),124 maturation inhibitor vivecon,125 NNRTIs like lersivirine (55)126 and dapivirine (56),127 and NRTIs like KP 1461 (57),128 apricitabine (58),129 elvucitabine (59),130 racivir (60),131 festinavir (61),132 alovudine (62),133 and amdoxovir (63) (Figure 12B, C, and D and Schemes 1 and 2).134

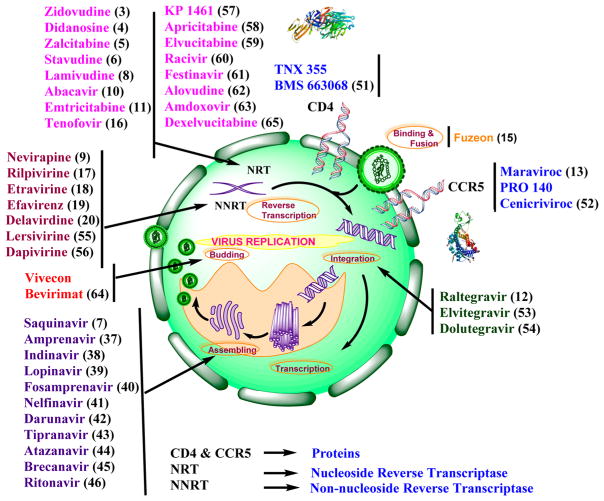

Bevirimat (64), a maturation inhibitor,135 and dexelvucitabine or reverset (65), a NRTI,136 are examples of discontinued anti-HIV-1 drugs that have undergone clinical trials (Figure 12E and Scheme 1). A schematic representation of all the anti-HIV-1 drugs that act at various stages of the viral replication cycle is shown (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Schematic representation of all the anti-HIV-1 drugs that act at various stages of viral replication cycle including the crystal structures of CD4427 and CCR5.428

3. PNEUMONIA

Pneumonia is the second leading cause of death globally, with around 3.3 million cases annually in the United States. The proper medications to completely treat the disease state do not exist.137 Pneumonia can occur in continuum to the acute influenza syndrome when it is caused by the virus alone, termed as “primary infection”, or it could be caused as a mixed infection of viruses and bacteria that is termed as “secondary infection”,138 which often is difficult to identify the etiological pathogen with many different bacterial strains such as Streptococcus pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Legionella pneumophila. The common cause of death due to pneumonia is mainly from the secondary bacterial infections due to one or several of the above mentioned strains leading to a combined bacterial/viral or post-influenza pneumonia.137

Influenza viruses belong to the family of Orthomyxoviridae and are enveloped with lipids, negative sense, single-stranded, segmented RNA viruses that exist in three forms: influenza A, B, and C. Influenza A virus is known to infect mammals, including horses and pigs, and birds, whereas influenza B and C are known to infect only humans.139

3.1. Past Pandemics

There are three known pandemics during the 20th century, which include the 1918 H1N1, Spanish flu; the 1957 H2N2, Asian flu; and the 1968 H3N2, Hong Kong flu. The Spanish flu pandemic resulted in higher morbidity and mortality compared to the 1957 or 1968 pandemics that are thought to have their origins in Asia. The 2009 A(H1N1) influenza virus was the first influenza pandemic in the 21st century.139

3.2. Transmission and Pathogenesis

The cause of transmission could be through the spread of droplets via small-sized aerosols produced from talking, coughing, or sneezing. Patients exposed to mechanical ventilation or intubations are infected through airborne transmission. The incubation period is about 24–48 h, and the viral shedding begins in 24 h in the absence of antiviral environment.138

Following inhalation, the virus deposits on the epithelium of the respiratory tract and becomes attached to the ciliated epithelial cells through the surface hemagglutinin. Some of the viral particles will be eliminated by the secretion of the IgA antibodies or mucociliary clearance. The viral particles then invade the respiratory epithelial cells and continue the viral replication. The newly formed viruses then infect the epithelial cells in large numbers and eliminate the synthesis of the critical proteins and lead to the death of the host cells.139

3.3. Treatment

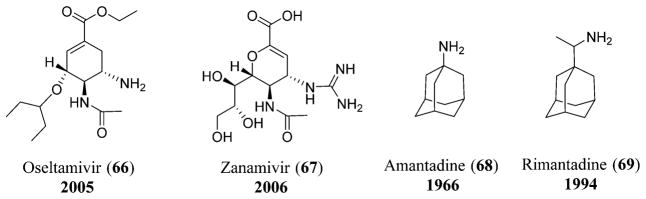

Various antiviral drugs used for the treatment of influenza include the neuraminidase inhibitors that include oseltamivir (66) and zanamivir (67)140 and adamantane drugs that include amantadine (68) and rimantadine (69).141 These antiviral drugs do not reduce the risk of complications, and vaccination is the only means of controlling or preventing influenza (Figure 14).142

Figure 14.

Neuraminidase inhibitors: oseltamivir (66) and zanamivir (67); adamantane drugs: amantadine (68) and rimantadine (69).

4. HEPATITIS B

Hepatitis B is the third leading cause of death globally and also the first major viral disease with which most people are chronically infected. Currently, more than 240 million3 people are carriers of hepatitis B and are at increased risk of developing hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and cirrhosis. Hepatitis B is a chronic necro-inflammatory liver disease caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) that could be further divided into HBeAg positive and negative chronic hepatitis B.143

4.1. Description of the Virus

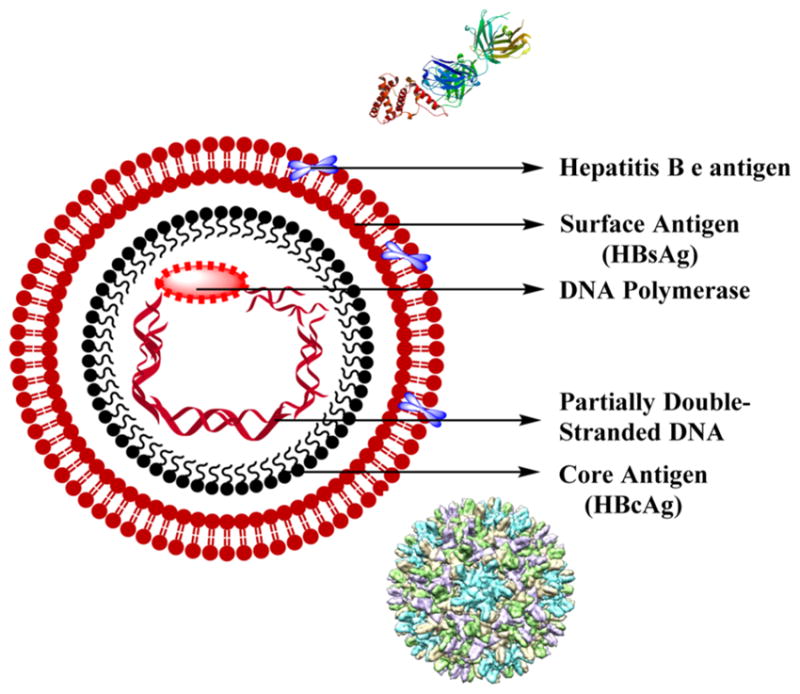

HBV is the smallest known DNA virus (hepadnavirus) possessing only 3200 bases in its genome. The genome consists of circular DNA that is partly double-stranded where one strand is termed “minus”, which is almost completely circular and includes overlapping genes encoding the replicative proteins like polymerase, X, and structural proteins like surface, core, and pre-S, while the other is termed “plus”, which is short and varied in length (Figure 15).144

Figure 15.

Structure of hepatitis B virus with crystal structure of HBV e antigen429 and cryo-electron microscopy (CryoEM) structure of HBV core antigen.430

ENH I and ENH II are two enhancer elements where ENH I functions competently in the hepatocytes only and is tissue-specific while ENH II acts on the surface gene promoters stimulating the transcriptional activity.144 HBV has a nucleocapsid that is a 27 nm sphere bearing a core antigen along with HBV e antigen, the viral DNA, and the DNA polymerase. The nucleocapsid is enveloped with a HBV surface antigen, HBsAg, which has the determinant a. In addition to the determinant a, the nucleocapsid also carries one of the two pairs of the subtypes w and r or d and y. This results in four subtypes of HBsAg that include ayr, ayw, adr, and adw, which represent the phenotypic expression of the HBV genotypes.145

The viral particle has four mRNA transcripts whose functions are known. The longest transcript is 3.5 kb that templates both for expression of polymerase and pre-core/core proteins and also for genome replication, while the second longest transcript that is 2.4 kb codes for HBsAg, pre-S1, and pre-S2. The third transcript is 2.1 kb that codes for HBsAg and pre-S2, while the smallest transcript is 0.7 kb encoding the X protein.144

The core gene possessing the pre-core region codes both the core antigen, HBcAg, and the cleavage product, HBeAg, which is an e antigen. Transcription of pre-core leads in cleavage by targeting the HBcAg to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and further secretion of HBeAg. HBcAg is the integral part of the core-particle and is essential for viral package. The pre-S gene on the surface codes the viral envelope and is essential for HBV attachment to hepatocytes.144

4.2. HBV Viral Replication

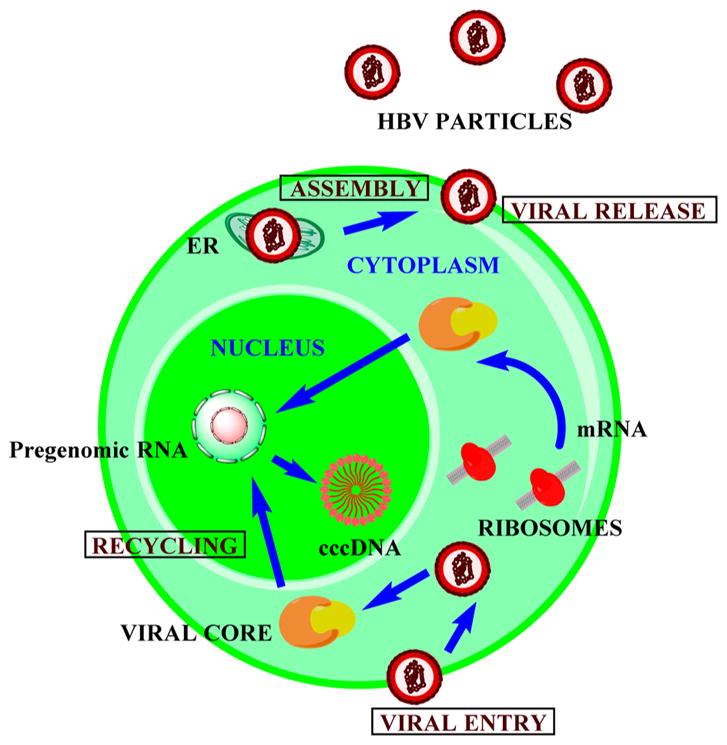

HBV viral replication is known to proceed in three stages where in the first phase the DNA strands are synthesized with the completion of the minus strand prior to the synthesis of the other strand. During the second phase, the virus polymerase acts as a reverse transcriptase, and in the final phase, the minus strand is primed at the 5′ end with a terminal protein while the plus strand is primed by oligoribonucleotide resulting from the genomic viral RNA.144

HBV binds to the surface of the cell followed by penetration into the cell. The viral core then transports into the nucleus where the circular viral DNA is further converted to covalently closed circular DNA, cccDNA, that acts as a template for the synthesis of viral RNA. HBV does not undergo integration during normal replication as seen with retroviruses. The minus strand DNA synthesis is initiated at the 3′ DR1 (short direct repeats) with polymerase as primer while the plus strand DNA synthesis is initiated at the 3′ DR2 and continues until the passage of the 5′ end of the minus strand. This leads to the production of an open circular DNA similar to the matured HBV. The matured core particles will then be packed into HBsAg/pre-S in the ER and exported out of the cell. The nucleus maintains a stable pool of cccDNA for the transport of freshly synthesized DNA back to the nucleus (Figure 16).144

Figure 16.

Viral replication of Hepatitis B virus.

4.3. Treatment

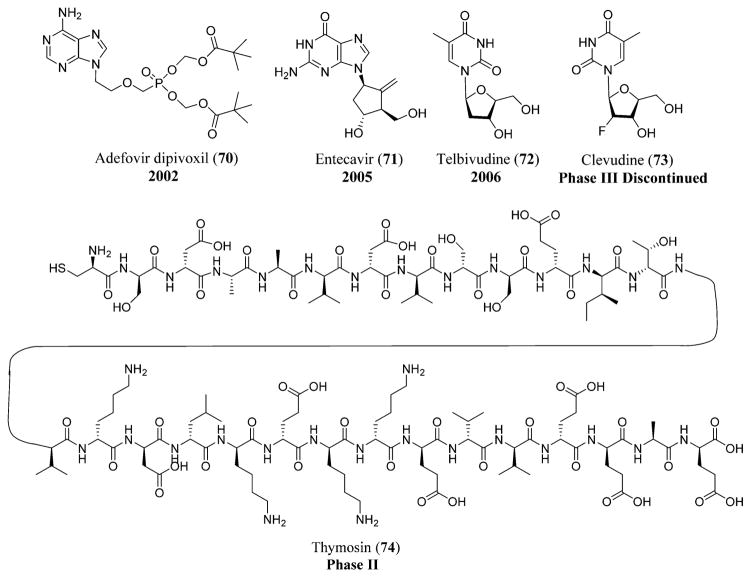

Lamivudine (8) is used in the treatment of HBV by inhibiting the viral DNA synthesis from becoming incorporated into the growing DNA and resulting in premature termination of the chain. Adefovir dipivoxil (70),146 a nucleotide analogue of AMP (adenosine monophosphate), is the prodrug of adefovir used in the treatment of HBV by inhibiting both the DNA polymerase and also reverse transcriptase activities by incorporating into the viral DNA and resulting in chain termination. Entecavir (71)147 acts by inhibiting the HBV replication at three different stages: DNA polymerase priming, negative-strand DNA reverse transcription, and positive-strand DNA synthesis.143 Entecavir (71) is also being used in persons suffering from chronic hepatitis B with decompensated liver disease.148 Telbivudine (72),149 a L-nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor,150 is another drug with selective potent antiviral activity against hepatitis B virus (Figure 17).143

Figure 17.

HBV drugs: adefovir dipivoxil (70), entecavir (71), telbivudine (72), clevudine (73), and thymosin (74).

Emtricitabine (11), a potent HIV inhibitor, is also used in the treatment of HBV by inhibiting the viral replication. Tenofovir DF (16), a nucleotide analogue also used in the treatment of HIV, is used in persons with hepatitis B,143 especially those who are resistant to the treatment of lamivudine (8).151 Clevudine (73),152 a pyrimidine nucleoside, is also effective in inhibiting the viral replication, but it is only approved in South Korea. Thymosin (74),153 a thymic-derived peptide, has the potency to stimulate the function of T-cells and is still under clinical trials (Figure 17 and Schemes 1 and 2).143

5. HUMAN PAPILLOMA VIRUS

Papillomaviruses were first discovered as viral particles in 1949 with around 73 more genotypes identified later. Papillomaviruses are found in mammals, birds, and reptiles like turtles. The mode of transmission is not clear, but the basal layer infections seem to play the major role. Anogenital human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is known to be transmitted through sexual contact.154

HPVs are non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the family Papillomaviridae. They are known to infect the skin mucosal surfaces and epithelial cells. The virus has a circular genome that is 8.0 kb and is encircled in a protein shell made of major, L1 and minor, L2 capsid proteins. There are seven ORFs (open reading frames) that encode the viral proteins with six “early” proteins, E1–E6. The early proteins are encoded by the transcripts present in the suprabasal and basal epithelial cells that allow viral transcription and replication. The E6 and E7 proteins play a major role in the cell transformation and immortalization. The L1 ORF encrypts the viral protein shell and its surface, while the L2 ORF encrypts the capsid mass, playing a major role in the viral genome encapsulation. The L1 protein also helps in assembling the structures to virus-like particles, VLPs.155

HPV results in various cancers and genital warts, especially cervical cancer, with more than 100 types of HPV;156 the first FDA-approved test for its identification was the cobas HPV test in 2011, which is a follow-up to the Pap test.157 The treatment of HPV does not include specific antiviral therapy except for the presence of lesions, and two vaccines have been licensed in the United States against HPV 16 and 18 types causing cervical cancer.156

6. RESPIRATORY SYNCYTIAL VIRUS

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is considered the major pediatric respiratory pathogen,158 which was first isolated from a chimpanzee,159 causing life threatening illness during the first few months. RSV has been placed in the genus Pneumovirus belonging to the family Paramyxoviridae.158

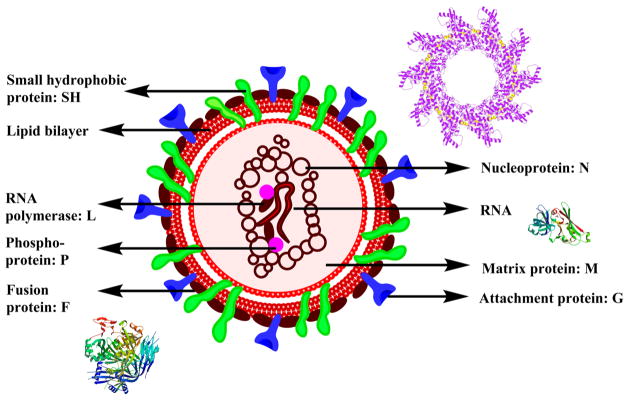

RSV is a medium-sized, linear, enveloped RNA virus with 10 viral polypeptides of which 8 are structural proteins with 7 largest that include SH, L, F, P, M, N, and G and two NS proteins, NS1 and NS2. The polymerase (L), nucleoprotein (N), and phosphoprotein (P) are the viral capsid proteins linked with the mRNA genome. The non-glycosylated membrane proteins M and M2 are the two matrix proteins. The attachment protein (G), the small non-glycosylated hydrophobic protein (SH), and glycosylated fusion protein (F) are all part of the transmembrane surface proteins. The G and F proteins play a major role in immunity (Figure 18).158

Figure 18.

Structure of RSV along with crystal structures of nucleoprotein,431 matrix protein,432 and fusion protein.433

6.1. Treatment

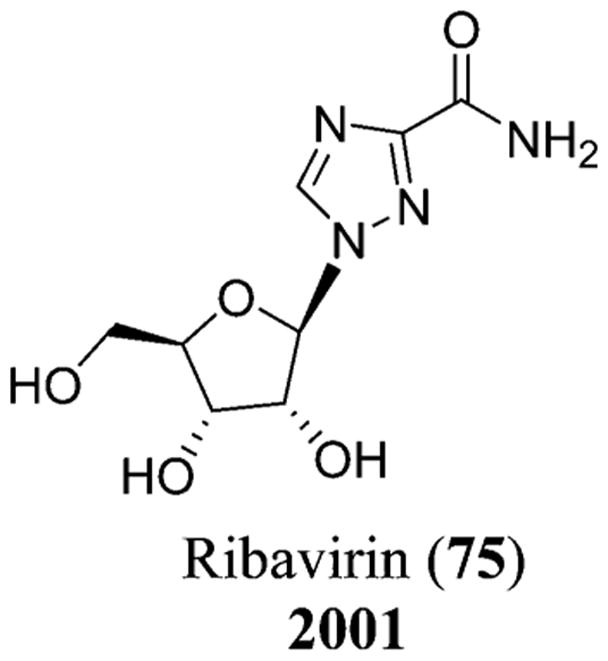

RSV is extremely contagious; at least half of the infants acquire RSV during their first year, and 40% of these result in lower respiratory tract diseases leading to pneumonia and/or bronchiolitis. Ribavirin (75), a synthetic nucleoside, has been approved for RSV infection, which is known to interfere with mRNA expression.158 Palivizumab (synagis), a humanized monoclonal antibody, IgG1κ,160 is another drug that was approved by the FDA in June 1998.161 Synagis is known to possess fusion and neutralizing inhibitory activity against RSV.160 The first vaccine for the treatment of RSV was developed in the 1960s, which was the alum-precipitated, formalin-inactivated vaccine (Figure 19).158

Figure 19.

Chemical structure of ribavirin (75).

7. HEPATITIS E

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the causative organism of hepatitis E and was initially termed as non-A, non-B hepatitis.162 HEV was recognized in the year 2004 as the major cause of acute hepatitis worldwide with four genotypes.163 HEV spread to other developing countries apart from Asia and is a major concern in pregnant women, leading to liver disease.164

HEV has been categorized in the genus Hepevirus belonging to the family Hepeviridae. Hepatitis E viral genome is 7.2 kb in size with three ORFs and 3′ and 5′ cis elements that play a major role in HEV transcription and replication. ORF1 encodes for replicase, methyl transferase, protease, and helicase; ORF2 encodes for the protein capsid, and ORF3 encodes for a protein of non-defined function.164 The natural host for HEV is humans, with animals acting as a possible reservoir in the amplification of the virus.164

The mode of transmission for HEV could be through transfusion. There is no specific treatment for HEV infection, but ribavirin therapy has been effective in some persons, although it is contraindicated with pregnant women. Combination of ribavirin (75) and interferon-α has also been used in chronically infected patients.163 Sofosbuvir (30) was reported at the EASL (European Association for the Study of the Liver) 2015 meeting to be a modest inhibitor of HEV in culture (Figure 19 and Scheme 1).165

8. DENGUE

Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever, DHF, are arthropod-borne viral infections166 known to be caused by the four virus serotypes, DEN 1–4, belonging to the genus Flavivirus. People in dengue endemic areas could have all four types of infections in their lifetime as cross-protective immunity is not provided when infected with one of the serotypes. Dengue is considered an urban disease, and the virus completes its cycle in humans via the day-biting mosquito, Aedes aegypti.167

8.1. Pandemics of Dengue

The first pandemic of dengue occurred in 1779–1780 in North America, Asia, and Africa, where simultaneous outbreaks were seen followed by a global pandemic after World War II in Southeast Asia. The geographical distribution of the multiple viral serotypes expanded to the Americas, and the Pacific region and Southeast Asia had their epidemic in the 1950s, leading to multiple hospitalizations and deaths by 1975 in many countries. The Maldives, India, and Sri Lanka had their first epidemics in the 1980s, whereas Pakistan had an epidemic in 1994. Although dengue was eradicated for a few years in the American region, it slowly migrated into the United States by 1995.167 Dengue started to emerge worldwide, and currently an estimated 100 million people are at risk annually with this viral disease.168

8.2. Dengue Virus

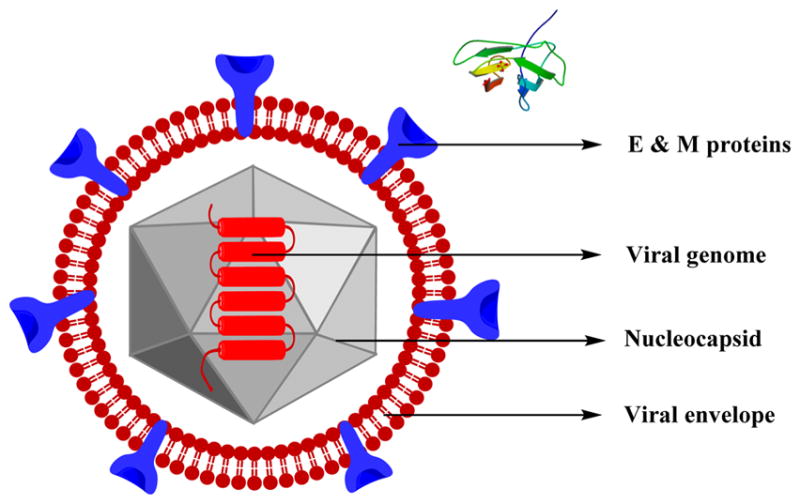

Dengue virus (DENV) belongs to the genus Flavivirus comprising over 70 viruses, most of which are arthropod-borne infections. The virus has a lipid envelope with an inner nucleocapsid comprising single-stranded RNA and capsid protein. The viral RNA is transformed into a polyprotein during infection, which is further cleaved into structural and non-structural (NS) proteins. The components of the matured viral particles include the envelope (E), the structural capsid (C), and the membrane (M), which are all thought to be involved in the viral replication (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Structure of dengue virus along with the crystal structure of the envelope protein (E)434

The NS proteins include NS1, NS2A–2B, NS3, NS4A–4B, and NS5, which are only expressed in the host cell and thought to play a role in viral replication. The function of NS1 is not completely understood. NS2B, NS3, and its cofactor are known to be involved in the process of the viral polyprotein, while NS3 also shows nucleotide triphosphatase and RNA helicase activities. NS2A and NS4A–4B are hydrophobic proteins, and their functions are not completely understood but are thought to be involved in anchoring viral replicase proteins to the cell membranes and contributing to the assembly of the virions; NS5 plays a role in the capping of the viral RNA progenies. NS4A also has a role in membrane alterations and helps in the complex formation of viral replicase.169

8.3. Transmission, Characteristics, and Treatment

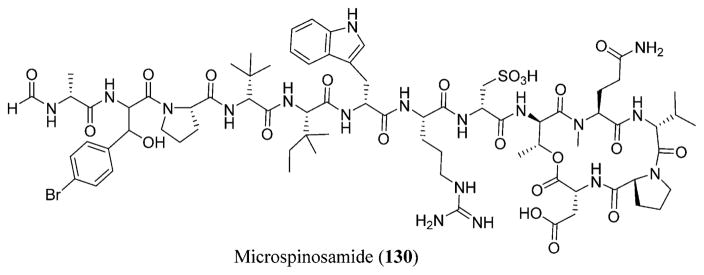

The primary vector of dengue is the Aedes aegypti mosquito, and transmission to humans occurs from the bites of the infected female mosquitoes. The incubation period is 4–10 days, and the infected mosquito has the ability to transmit the virus for the rest of the insect’s life. The infected humans serve as the source of the virus for the uninfected mosquitoes and could transmit the infection in 4–5 days during which the appearance of the first symptoms occur. A secondary vector for the spread of dengue is Aedes albopictus.168

Dengue fever (DENF) is a severe, flu-like infection affecting adults, infants, and young children, leading to occasional deaths. The fever is usually accompanied by vomiting, rash, severe headache, joint and muscle pains, pain behind the eyes, and swollen glands. The symptoms last for about 2–7 days following the incubation period. Dengue becomes deadly when one or more of the following symptoms occur: organ impairment, plasma leaking, respiratory stress, fluid accumulation, or severe bleeding.168 Currently, there is no proper treatment or vaccination for DENF. In cases of severe dengue, the medical practitioners and nurses give the necessary medical care and maintain the volumes of the patient’s body fluids.168

9. SEVERE ACUTE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

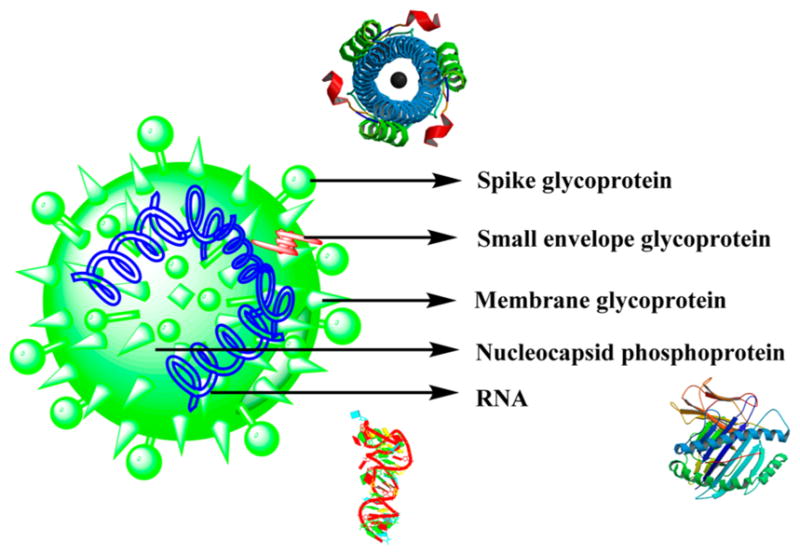

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is caused by a coronavirus170 and could be termed as atypical pneumonia, first identified in China in Guangdong Province, that later resulted in the spread to many countries.171 Coronaviruses belong to the family that includes enveloped viruses where the replication occurs in the host-cell cytoplasm. They include a plus sense, single-strand RNA with a 3′polyadenylation tract and a 5′cap structure. Following the infection, the 5′ORF of the virus is transformed to a polyprotein that is further cleaved by the proteases, releasing many nonstructural proteins that include the ATPase helicase, Hel, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which are responsible for the viral replication and protein synthesis (Figure 21).171

Figure 21.

Structure of the SARS virus along with the crystal structures of spike glycoprotein,435 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein,436 and RNA.437

The viral membrane includes the major proteins spike, S, and membrane, M, which insert into the ER of the Golgi compartment while the RNA plus strands accumulate in the nucleocapsid protein. The protein–RNA complex is then associated with the membrane protein of the ER, and the formed viral particles bud into the ER lumen. The viral particles then migrate into the Golgi complex, exiting the cell by means of exocytosis.171

There are no FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of SARS, although a few drugs like ribavirin have been considered but proven to be ineffective in preventing SARS viral growth inhibition.172 The literature also shows the combination therapy with lopinavir (39)–ritonavir (46) for the treatment of SARS, which is thought to reduce the viral load.173

10. NOROVIRUS

Noroviruses belonging to the family Caliciviridae (derived from calyx, meaning “cup” in Greek)174 and the genus Norovirus were discovered in the year 1972 and were previously called Norwalk-like viruses. Like other viruses, this virus also has a single-strand, plus sense RNA of 7.5 kb including three ORFs. ORF1 is known to encode the non-structural polyprotein that could be cleaved by the viral protease into 6 proteins, while ORF2 and 3 encode the major and minor capsid proteins, VP1 and VP2, respectively. The VP1 protein is involved in the formation of two domains: shell, S, and protruding, P (P1 and P2). The P2 subdomain is further involved in immune recognition and cellular interactions.175 The virus-encoded 3C-like cysteine protease [3CLpro] processes the mature polyprotein for the generation of the six non-structural proteins: p48 [NS1 and NS2], NTPase/RNA helicase [NS3], p22 [NS4], VPg [NS5], protease [NS6], and a RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [RdRp] [NS7].176

Five genotypes of noroviruses are known from the molecular characterization where GI, GII, and GIV are found in humans while GIII and GV strains are seen in cattle and mice, respectively.175 Noroviruses are the major causative organisms of acute gastroenteritis.177 The common genotype responsible for many of the outbreaks worldwide is GII.174

10.1. Transmission and Treatment

The primary mode of transmission includes either the oral or fecal routes, and the other common routes include water- or foodborne and person-to-person contacts. Humans are thought to be the only hosts for human noroviruses. The virus can sustain a wide range of temperatures and exists in various food items including fruits, vegetables, and raw oysters along with drinking water. Noroviruses also result in repeated infections and undergo mutations, resulting in the evolution of novel strains infecting the hosts. The disease results in fever, watery diarrhea, and vomiting along with other symptoms such as myalgias, headaches, and chills.174

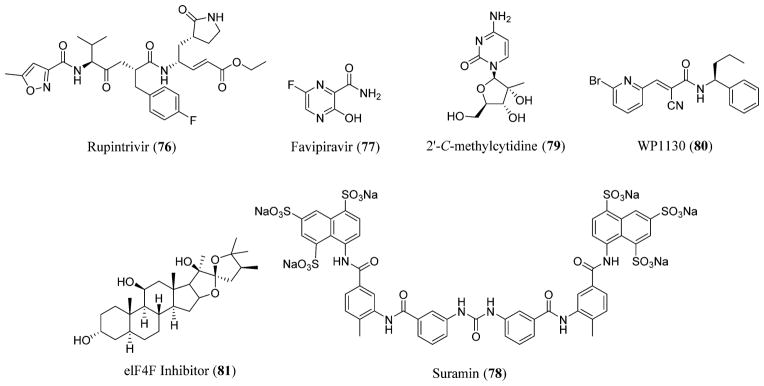

There are no known FDA-approved antiviral agents for the treatment of norovirus gastroenteritis except for oral rehydration with electrolytes and fluids. Antisecretory and antimotility drugs are used in adults suffering from diarrhea.174 Ribavirin (75) and interferons are known to inhibit the Norwalk viral replication whose therapeutic efficacy needs further evaluation.178 Rupintrivir (76), formerly known as AG7088, an irreversible inhibitor of 3CLpro that possessed in vitro antiviral activity against picornaviruses,179 is known to display anti-norovirus activity.180 Favipiravir (77), also known as T-705, currently in advanced clinical developments for influenza virus, is considered to be an RdRp inhibitor of norovirus, inhibiting the viral replication.181 Suramin (78), a naphthalene sulfonate derivative, is another RdRp inhibitor that is known to inhibit the genome replication and prevent the synthesis of viral sub-genomic RNA.182 2′-C-Methylcytidine (79), a nucleoside analogue, is considered to be a potent inhibitor of norovirus-induced diarrhea and mortality in vitro in a mouse model.183,184 Certain deubiquitinase and elF4F inhibitors (80–81) are considered promising candidates in the development of norovirus therapeutics (Figures 19 and 22).185,186

Figure 22.

Norovirus inhibitors: rupintrivir (76),438 favipiravir (77), suramin (78),439 2′-C-methylcytidine (79), deubiquitinase [WP1130] (80), and elF4F inhibitors (81).

11. MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME CORONAVIRUS

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a coronavirus that could lead to severe pulmonary disease in humans,187 was first identified in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in September 2012,188 from a patient suffering from renal failure and pneumonia. The infection is known to be linked geographically to the Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and Qatar.189

MERS-CoV belongs to the subfamily Coronavirinae that represents a new species in the genus Betacoronavirus that currently includes Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 and Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4. This novel virus seem to relate to the viruses belonging to the families Nycteridae and Vespertilionidae that include insectivorous African and European bats, respectively. The infection is thought to be zoonotic primarily with limited transmission from human to human.189

To date, there are no effective antivirals against MERS-CoV and emphasis is placed on organ support for renal and respiratory failures. IFN-α has shown inhibition of in vitro MERS-CoV replication while its action in vivo is unknown.190

12. WEST NILE

West Nile fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease that led to sporadic outbreaks of equine and human diseases in Europe. The largest outbreak occurred in 1996–1997 in Romania, near Bucharest, which was considered the major arboviral illness in Europe.191

West Nile virus (WNV), a member of the Japanese encephalitis, belongs to the genus Flavivirus of the family Flaviviridae. This virus was initially isolated from the blood of a febrile female in Uganda in the year 1937 from the West Nile district. The primary vectors of the virus include mosquitoes, predominantly belonging to the genus Culex, and the primary hosts are wild birds.191

Currently, there are no FDA-approved drugs or licensed vaccines available for the treatment of WNV.192 An adjuvant therapy used in the treatment of WNV encephalitis is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).193

13. HEPATITIS D AND A

Hepatitis D is caused by the hepatitis D virus (HDV) and leads to severe liver disease. Hepatitis D is uncommon in the United States, and it generally occurs as a coinfection with hepatitis B virus.194 HDV is a hepatotropic defective virus that is dependent on the HBV for its envelope provision. HDV includes a hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAg, and the RNA genome, which is a rodlike, circular structure possessing self-ligation and autocatalytic cleavage properties. RNA polymerase II effects the RNA replication, and the only protein that is encoded by the HDV-RNA is the hepatitis D antigen, HDAg, whose short and long forms play a role in the morphogenesis and replication of the virus.195

The only treatment available for chronic hepatitis D is alpha interferon, although inhibiting HBV results in a decrease in hepatitis D virus replication.195 Hepatitis D complications are preventable with hepatitis B vaccine.196

Hepatitis A is caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV), an enterovirus, belonging to the family Picornaviridae.197 The large epidemics of hepatitis A occurred in the years 1954, 1961, and 1971.198 HAV has a single-molecule RNA surrounded by a small protein capsid of 27 nm diameter and has an incubation period of 10–50 days.197

Chronic infection is not seen with hepatitis A, and the common mode of transmission is through person-to-person contact with oral ingestion as the major route. The clinical illness could be protected by giving immune globulin during the incubation period or before the exposure to the HAV, and certain hepatitis A vaccines are also effective against the disease.198

14. ROTAVIRUS

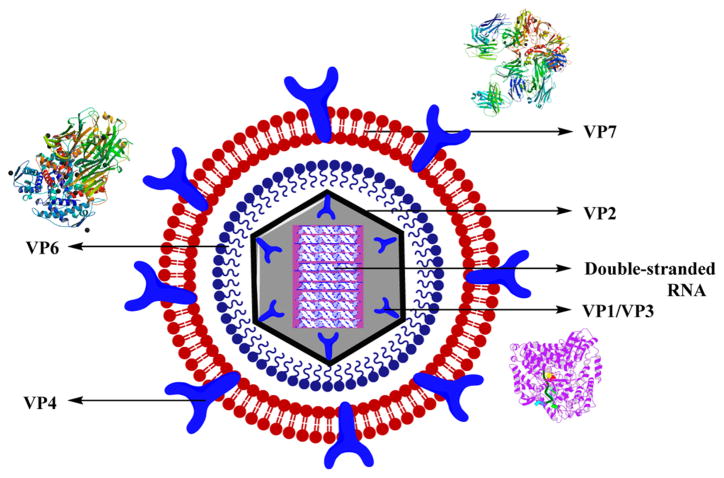

Rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrhea among children worldwide.199 The viral genome includes an 11-segmented double-stranded RNA that is enclosed in a three-layered viral capsid with four major capsid proteins–VP2, VP4, VP6, and VP7–and two minor proteins–VP1 and VP3. The co-expression of the major capsid proteins as different combinations resulted in the production of stable virus-like particles (VLPs) that are responsible for the maintenance of the functional and structural characteristics of the matured viral particles. The outer layer is composed of the glycoprotein, VP7, and dimeric spikes of VP4 responsible for inducing neutralizing antibodies, with VP4 as the viral hemagglutinin. The inner capsid has VP6 as the major protein, which constitutes more than 80% that is known to possess RNA polymerase activity. The core part includes VP1–VP3, and the 11 double-stranded RNA segments with VP2 covering >90% of the core-protein mass (Figure 23).200

Figure 23.

Structure of rotavirus along with the crystal structures of VP7,440 VP1,441 and VP6.442

Rotavirus is known to infect the intestine, leading to diarrhea that could last for about 8 days. There is no treatment for rotavirus infection, and this disease could be prevented through vaccination. The severity of the disease lies in dehydration that can be treated through fluids.201

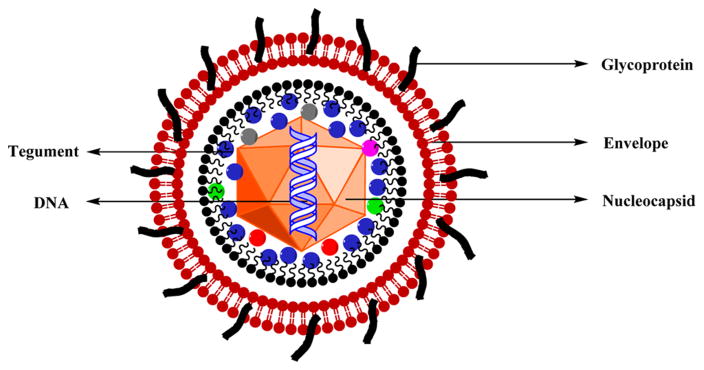

15. SHINGLES

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a herpesvirus leading to both chicken pox (varicella) and shingles (herpes zoster). The virus includes a nucleocapsid encapsulating the core with a linear double-stranded DNA whose arrangement is done in short and long unique segments with 69 ORFs with about 125 000 bp and a tegument made of protein that separates the capsid from the lipid envelope. The lipid envelope incorporates the main viral glycoproteins. VZV is the smallest known human herpesvirus (Figure 24).202

Figure 24.

Structure of varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

People infected with chicken pox are prone to shingles that can occur in all ages with the risk increasing with growing age. Chicken pox develops into blisters or rash, meaning that the virus is dormant in the nerve cells and can reactivate by producing shingles203 and travel through the nerves to the skin. Inflammation is seen in the nerves leading to after-pain, termed as post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) that could be chronic and severe.204

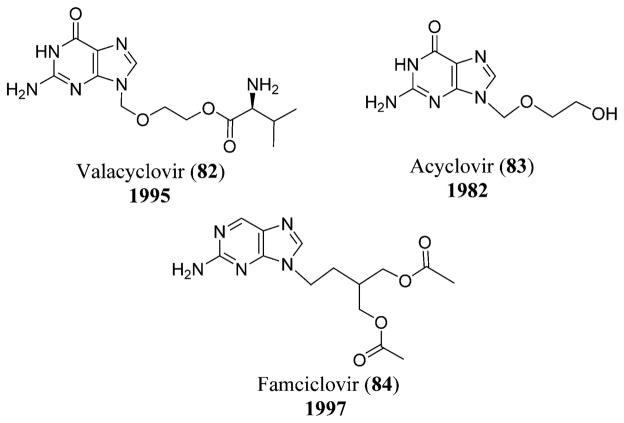

VZV transmission occurs through respiratory route, and zostavax is the vaccine used against VZV that has been approved by the FDA and is the only U.S.-licensed vaccine known to date.204 The antiviral drugs that have been approved for the treatment of VZV infections include valacyclovir (82),205 acyclovir (83),206 and famciclovir (84),207 which replaced the nucleoside analogues IFN-α and vidarabine or Ara-A (2). Acyclovir (83) and valacyclovir (82) (a valine ester derivative of acyclovir) act as competitive inhibitors and result in the chain termination of the viral DNA polymerase.202 Varizig (varicella zoster immune globulin) was approved by the U.S. FDA in December 2012 as an orphan drug that could be given after exposure to VZV (Figure 25 and Scheme 2).208

Figure 25.

Chemical structures of valacyclovir (82), acyclovir (83), and famciclovir (84).

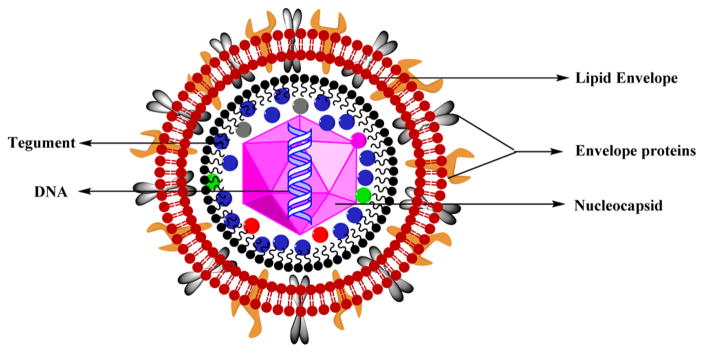

16. HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

Genital herpes, a sexually transmitted disease (STD), is caused by two types of viruses, herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. It is highly common in the United States, and its transmission occurs through anal, oral, or vaginal sex with any person infected with the disease.209

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the largest herpes virus belonging to the family Herpesviridae. The viruses belonging to this family are enveloped viruses including a tegument, a capsid, and a genome. The viral envelope is fragile, and the space between the capsid and the viral envelope is called a tegument, which usually contains the glycoproteins and the enzymes necessary for the viral replication. The nucleocapsid is icosahedral with about 150 hexameric and 12 pentameric capsomeres that are doughnut-shaped. The viral genome is a linear, double-stranded DNA wrapped in a core (Figure 26).210

Figure 26.

Structure of HSV.

HSV-1 and -2 have similar genome structures with 83% homology in the protein-coding and 40% homology in the sequencing regions. HSV-1 is associated with oral disease whereas HSV-2 is associated with genital disease in certain parts of the world such as Sub-Saharan Africa, where HSV-1 is known to occur in childhood and HSV-2 is sexually transmitted. In contrast, based on the anatomical site, HSV-2 is responsible for genital herpes in developed countries.211

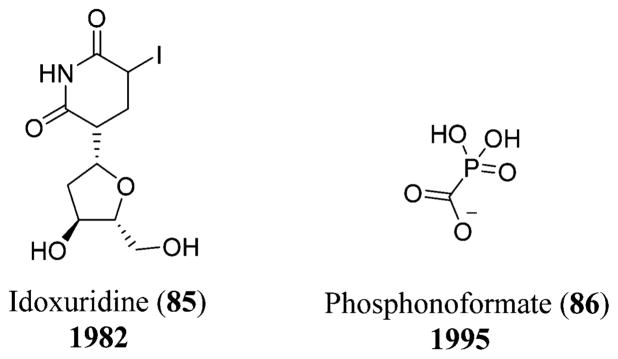

Current medications for the treatment of HSV infection include antiviral agents like acyclovir (83), vidarabine (2), idoxuridine (85),212 ribavirin (75), and phosphonoformate (86),213 of which acyclovir (83) or its valyl prodrug form known as valacyclovir are widely used. Acyclovir (83), a purine analogue, acts as a substrate for the viral thymidine kinase, thereby inhibiting the viral DNA polymerase selectively. Because of the viral resistance to acyclovir (83), new antivirals have evolved for the treatment of HSV. Phosphonoformate (86), which is a derivative of phosphonoacetic acid, is a potent inhibitor of the HSV DNA polymerase (Scheme 2 and Figures 19, 25, and 27).214

Figure 27.

Chemical structures of idoxuridine (85) and phosphonoformate (86).

17. EBOLA VIRUS

Ebola hemorrhagic fever (Ebola HF) is a viral disease caused by the Ebola virus (EBOV) that gains importance in this review due to the current, ongoing outbreak in West Africa along with Guinea, Liberia, and Uganda since March 2014.215 Reports showed around 21 deaths and 37 cases that have been reported from Guinea, 13 cases from Sierra Leone, and 1 suspected case in Liberia between May 29 and June 1 of 2014.216 The number of ebola deaths has been raised since then to 7 857 between December 24 and 27 of 2014, with 3 413 deaths in Liberia, 2 732 deaths in Sierra Leone, 1 697 deaths in Guinea, 8 deaths in Nigeria, 6 deaths in Mali, and 1 death in the United States.217 The first human outbreak of Ebola virus that has been recorded was in 1976 followed by major outbreaks in 2001 and 2003 in Gabon and the Republic of Congo.218

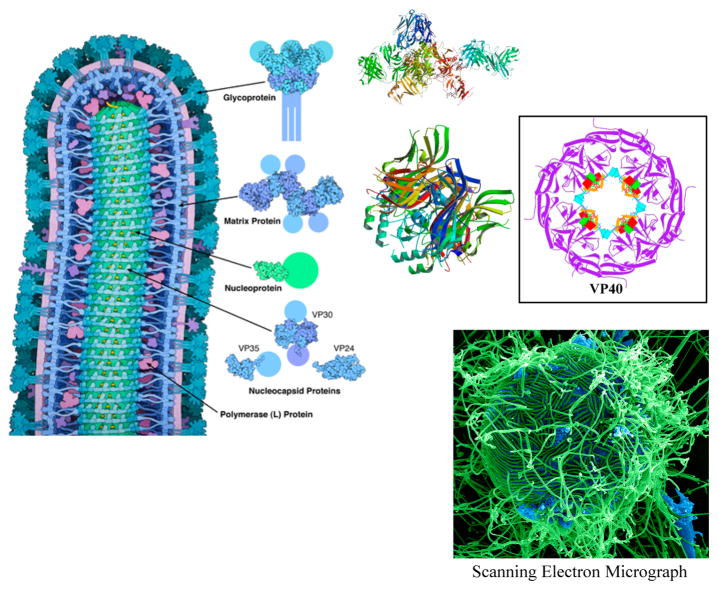

17.1. Description of EBOV

The EBOV is a non-segmented, enveloped, negative strand RNA virus belonging to the family Filoviridae. Four species of EBOV (Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, Reston, and Zaire) are known to cause disease in humans, with Zaire being associated with the highest human lethality. The genome consists of seven genes responsible for the synthesis of eight proteins.219

Ebola virus is enclosed with a membrane of the infected cell enveloped with ebola glycoproteins. The inner membrane is supported with a layer of matrix proteins and possesses a central cylindrical nucleocapsid that is necessary for the storage and delivery of the RNA genome. The ebola glycoprotein binds to the cell-surface receptors to get the genome inside. The EBOV shares many features similar to the HIV envelope glycoprotein and influenza hemagglutinin covered with carbohydrate chains that would help the virus hide from the immune system. The virus could transform into a different shape when bound to the cell surface, dragging the cell and the virus close enough to cause membrane fusion.220

The matrix protein, also called VP40, helps in the shape and budding of the virus. The proteins present on the membrane help make the connection between the nucleocapsid and the membrane. The nucleocapsid, present at the center of the virus, helps protect the viral genome; however, the nucleoprotein subunits are not rigid as in other viruses, showing a wavy structure.220

Transcription of the fourth gene leads to the expression of glycoprotein that is transmembrane-linked (GP) and a secreted glycoprotein (sGP). GP remains the key target for the design of entry inhibitors and vaccines. GP is cleaved by furin post-translationally yielding GP1 and GP2 subunits, which are disulfide-linked. GP1 is known to effect the attachment to the host cells while GP2 facilitates the fusion of the host and viral membranes (Figure 28).219

Figure 28.

Structure of Ebola virus.220 Reprinted with permission from ref 210. Copyright 1989 American Chemical Society. Image from the RCSB PDB October 2014 Molecule of the Month featured by David Goodsell (DOI: 10.2210/rcsb_pdb/mom_2014_10)], crystal structures of glycoprotein,219 matrix proteins,443,444 and electron scanning microscopic image445 (Courtesy: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, http://www.niaid.nih.gov/news/newsreleases/2014/Pages/EbolaDisparities.aspx).

There is no standard treatment for EBOV HF, but it is limited to the supportive therapy that includes balancing the electrolytes and fluids of the patients, maintaining blood pressure and oxygen supply, and treating for further complicated infections. The early symptoms of EBOV HF include fever and headache, which are difficult to diagnose for EBOV. No known treatments are yet available for humans for the treatment of Ebola virus,221 but recently favipiravir (77), a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative, showed successful suppression of the replication of Zaire EBOV both in vitro and in vivo at an IC90 of 110 μM.222

18. MARINE DRUGS FOR THE TREATMENT OF HIV/AIDS

Although there are many drugs available commercially from synthetic sources, limitations including drug resistance, side effects, cell toxicity, and long-term drug treatment are all possible explanations for the failure of the previously mentioned anti-HIV drugs. In addition, the evolution and development of nucleoside antivirals reveal the tremendous potential marine products have for the identification of novel prototypes and also reveals the necessity of developing drugs from natural resources such as the marine environment.223 Marine species cover over two-thirds of the planet, making them a significant source for the production of novel compounds with possibly fewer adverse effects and higher inhibition activity.224 The compounds obtained from marine sources that are discussed in the following sections were found to possess anti-HIV-1 activity (Figure 29).

Figure 29.

Schematic representation of the marine metabolites that are active at various stages of the viral replication cycle including the crystal structure446 of lectin.

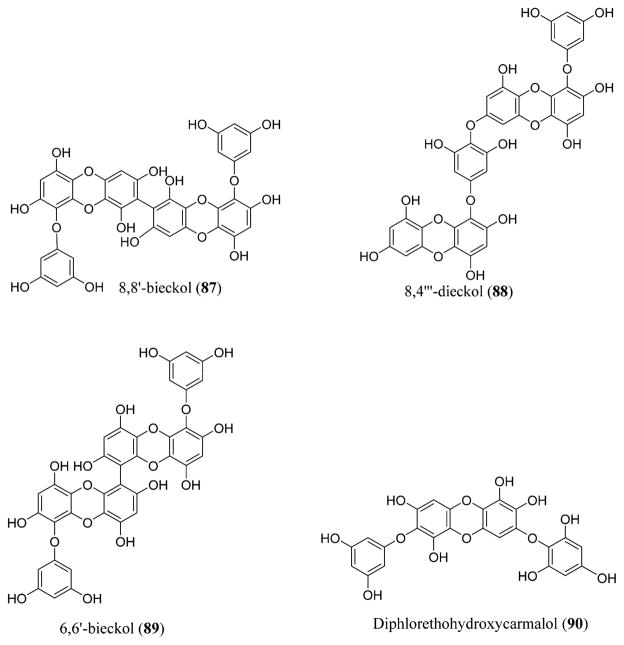

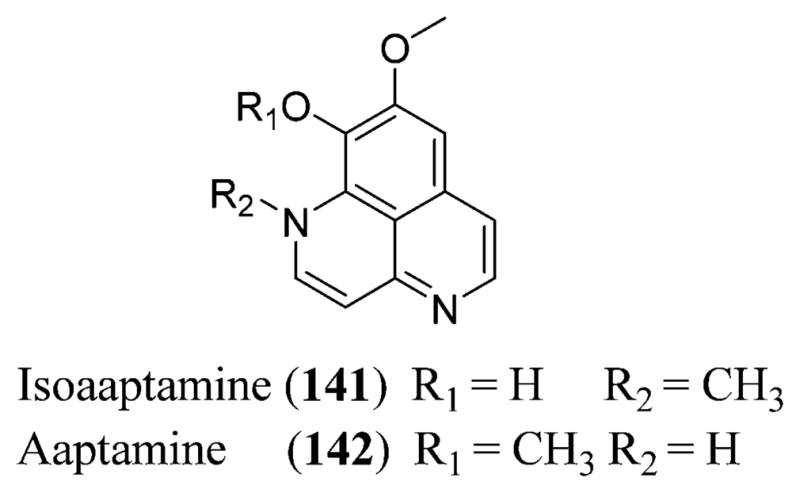

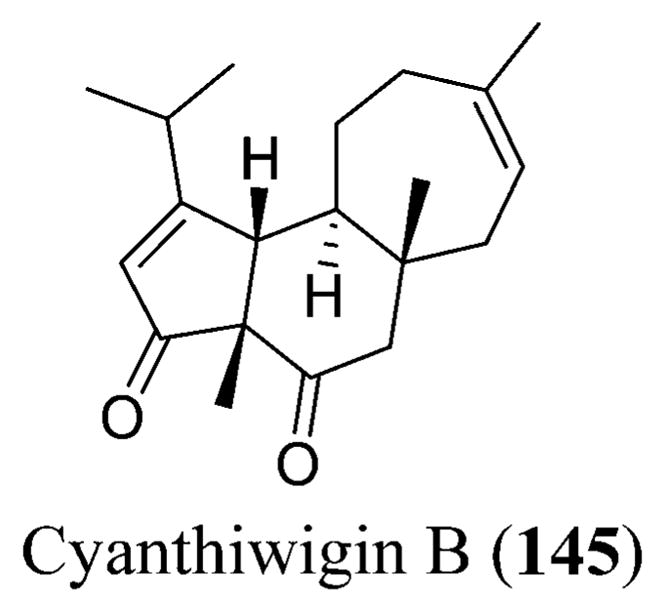

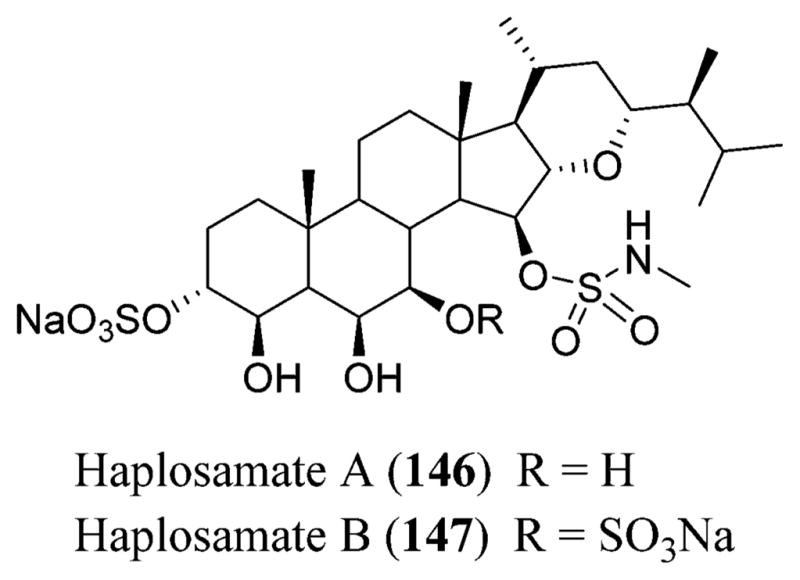

18.1. Phlorotannins

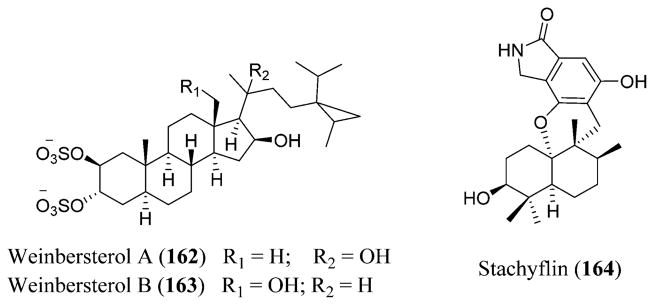

Phlorotannins are tannin derivatives that were isolated from brown algae and are biosynthesized by the polymerization of the phloroglucinol monomer units acquired from the pathway of acetatemalonate. These are highly water-soluble compounds.225,226 They can be classified into four different categories: phlorotannins containing an ether linkage (fuhalols and phlorethols), phenyl linkage (fucols), phenyl and ether linkage (fucophloroethols), and dibenzodioxin linkage (eckols).227 8,4‴-Dieckol (88) and 8,8′-bieckol (87) are isolated from Ecklonia cava, a brown algae, and show inhibitory activity on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and protease at inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 5.3 and 0.5 μM, respectively.228 This is due to the inhibition of the gp41 six-helix bundle formation.229,230 6,6′-Bieckol (89), a natural derivate in Ecklonia cava, possesses lytic effects, causes p24 antigen production, and has inhibitory activity against HIV-1-induced syncytia formation. It showed selective inhibition against the HIV-1 entry and the activity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase enzyme at an IC50 of 1.07 μM.231 Diphlorethohydroxycarmalol (90), derived from Ishige okamurae, also possessed inhibitory activity against HIV-1. It inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and integrase at IC50 values of 9.1 and 25.2 μM, respectively (Figure 30).232

Figure 30.

Phlorotannins 8,8′-bieckol (87), 8,4‴-dieckol (88), and 6,6′-bieckol (89) isolated from a brown algae, Ecklonia cava, and diphlorethohydroxycarmalol (90) isolated from Ishige okamurae.

ADMET predictor shows that 8,8′-bieckol (87), 8,4‴-dieckol (88), 6,6′-bieckol (89), and diphlorethohydroxycarmalol (90) violate three criteria of the Lipinski guidelines. These compounds also show low permeability and tend to be poor at permeating the cell membranes based on the polar surface area.

6,6′-Bieckol (89), a phloroglucinol derivative, did not exhibit any cytotoxicity at concentrations that inhibited HIV-1 replication almost entirely.231 The phloroglucinol derivatives exhibited HIV-1 inhibition similar to that of flavonoids where they block the interaction between reverse transcriptase (RT) and the RNA template.233 6,6′-Bieckol (89) is a viral entry inhibitor, and so the above-mentioned factors like permeability may not be a problem; this could be considered as an important lead as this compound could inhibit the viral entry.

Most of the currently synthesized and FDA-approved drugs could only inhibit the virus at various replication stages. Hence, the above-mentioned limitations for various compounds could be overcome by changing the route of administration (using intravenous or subcutaneous (SC) instead of oral) (Table S1).

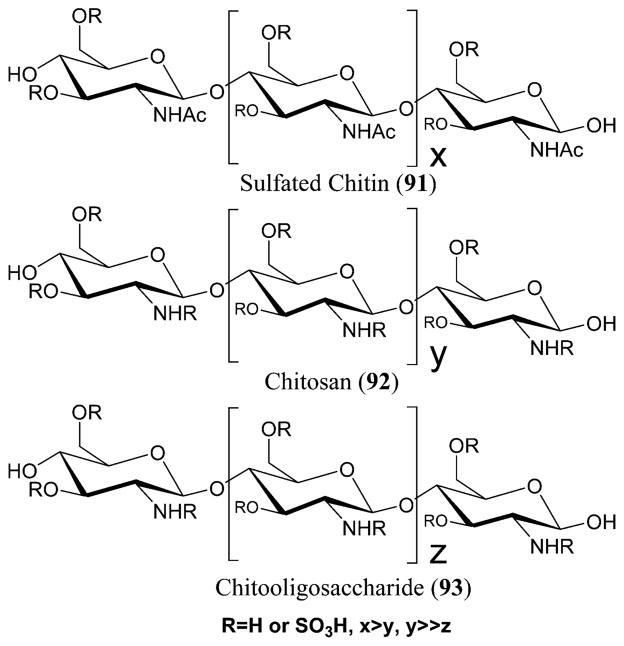

18.2. Chitin, Chitosan, and Chitooligosaccharide Derivatives

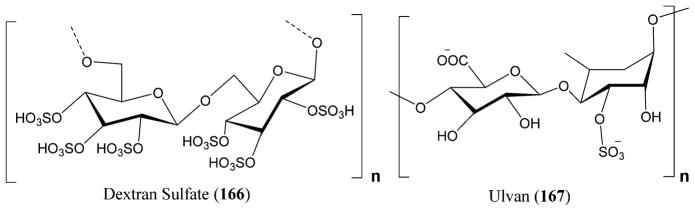

Chitin is widely found in crustaceans, fungi, invertebrates, and insects.234 It is a long-chain polymer of N-acetylglucosamine that is most abundantly seen in the shells of shrimp and crabs.235 Chitosan is formed by deacetylating chitin. The sulfated derivatives of chitin (91) and chitosan (92) possess activities including anti-HIV-1, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and others.223 N-carboxymethylchitosan N,O-sulfate (NCMCS), a derivative of N-carboxymethyl chitosan, is known to inhibit the transmission of HIV-1 in human CD4+ cells. This inhibition is due to the blockade of the interactions between the glycoprotein receptors present on the viral coat and the target proteins present on the lymphocytes, thereby inhibiting the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase.236 The sulfation at the 2 and 3 positions led to the complete inhibition of HIV-1 infection to T-lymphocytes at 0.02 μM concentrations without any cytotoxicity. These results show that the biological activity of the sulfated chitins can be controlled by changing the sulfate group position.237 Chitosan is converted to chitooligosaccharides to improve its water solubility and, therefore, its biological activity.223

Low molecular weight sulfated chitooligosaccharides (SCOSs) (93) are known to possess anti-HIV activity.238 They show lytic effects and inhibit HIV-1-induced syncytia formation at median effective concentration (EC50) values of 1.43 and 2.19 μg/mL, respectively. The p24 antigen production could be suppressed at EC50 values of 7.76 and 4.33 μg/mL for HIV-1Ba-L and HIV-1RF, respectively.238 They also inhibited viral entry and cell fusion by preventing the bond between gp120 of the HIV and CD4 surface receptor (Figure 31).223

Figure 31.

Sulfated chitin (91), chitosan (92), and chitooligosaccharide (93) derivatives.

ADMET predictor shows that sulfated chitins violate three criteria of the Lipinski guidelines whereas the chitosans violate all four criteria. In addition, they also show low permeability, low flexibility, and a tendency to not permeate the cell membranes. However, as per the mechanism of action, these are known to inhibit the viral entry and fusion and so permeability could not be considered as a limiting factor.

SCOSs inhibit HIV-1 replication by binding to the V3 loop of gp120 and thereby interfering with the gp120–CD4 binding.238 They possess a high rate of intestinal absorption, which is a crucial property for a drug candidate.239 The main drawback with chitosan and its sulfated oligosaccharide derivatives is its high anti-coagulant activity that limits SCOS to be clinically tested and approved on infected HIV subjects.240 The above limitation could be overcome by SAR (structure–activity relationship) studies and by trying various medicinal chemistry alterations to alleviate the anticoagulant activity (Table S1).

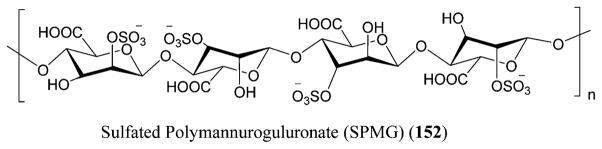

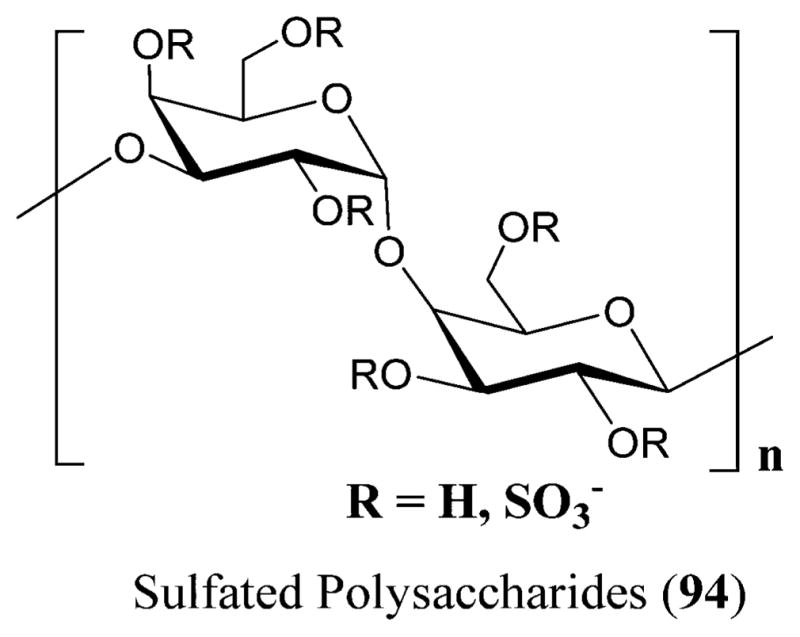

18.3. Sulfated Polysaccharides

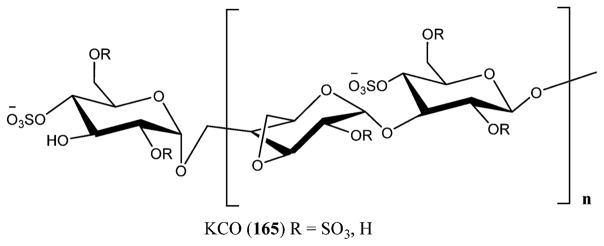

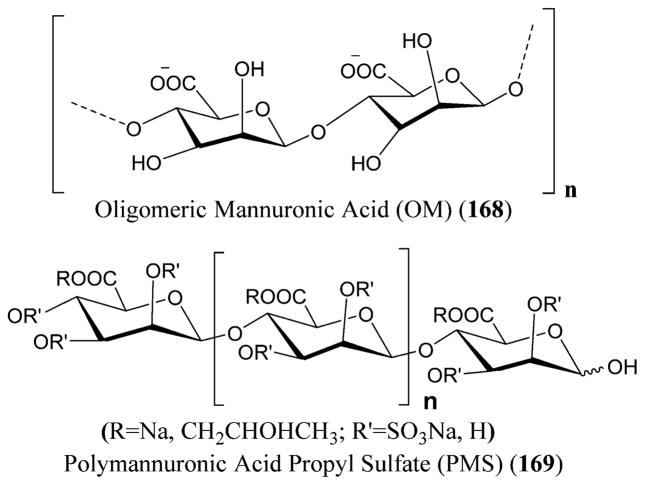

Sulfated polysaccharides (94) are macromolecules that are chemically anionic and present in marine algae along with mammals and invertebrates, although marine algae are the major source.241,242 They also possess anti-HIV-1, along with anticancer and anticoagulant activities (Figure 32).223

Figure 32.

Sulfated polysaccharides (94) isolated from red seaweeds.447

The SPs (sulfate polysaccharides) prevent the virus from attaching to the target molecules on the cell surface. The SPs possess a binding site on the CD4 that is relatively similar to the HIV–gp120 binding region.243 Hence, by binding to this lymphocyte, the SPs inhibit the binding of the monoclonal antibodies to the initial two domains of the CD4,244 thereby disrupting the CD4–gp120 interaction. The anti-HIV activity of the SPs is by shielding off the positively charged sites on the V3 loop of the gp120 protein, thereby preventing the virus attachment to the cell surface.245

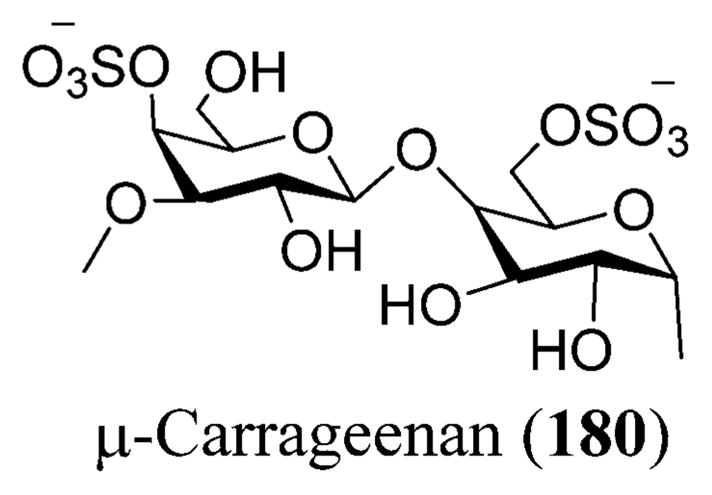

The SPs from red algae are also known to possess anti-HIV-1 activity.246 Schizymenia dubyi, a red algae, produces a sulfated glucuronogalactan that is known to possess anti-HIV-1 activity. This polysaccharide suppressed the syncytial formation completely at a concentration of 5 μg/mL and also inhibited the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase at the same low concentration without any cytotoxicity to the MT4 cells.247 Its mechanism of action involves inhibiting the attachment of virus to the host cell. Nakashima et al. prepared an extract of citrate buffer, sea algal extract (SAE) from the marine red alga Schizymenia pacif ica, that showed inhibition against HIV replication and HIV reverse transcriptase. SAE is a sulfated polysaccharide with a molecular weight of ~2 000 000 belonging to the family of λ-carrageenan that includes 3,6-anhydrogalactose (0.65%), sulfonate (20%), and galactose (73%), with the sulfate residues being responsible for the inhibition of the HIV reverse transcriptase at an inhibitory dose of 9.5 × 103 IU/mL.248,249

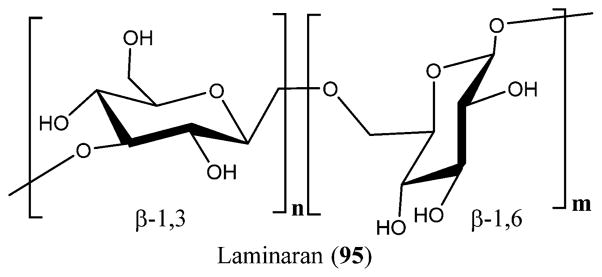

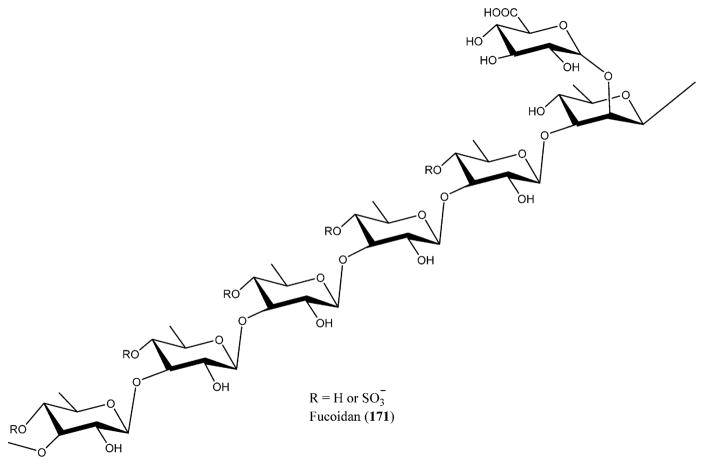

Brown algae are also known to produce SPs with anti-HIV-1 activity via a different mechanism of action.223 Fucans are present mainly in brown algae, and they have high molecular weights and possess a repeated chain of sulfated fucose. Fucans derived from the seaweed species of Lobophora variegate, Spatoglossum schroederi, Fucus vesiculosus,250 and Dictyota mertensii inhibit the reverse transcriptase of HIV-1. The galactofucan fractions of L. variegate showed reverse transcriptase inhibition at 1.0 μg/mL concentration with 94% synthetic polynucleotides inhibition. Fucan A from D. mertensii and S. schroederi displayed inhibition activity against the reverse transcriptase enzyme at 1.0 mg/mL with 99.3% and 99.03% inhibition, respectively. Fucan B from S. schroederi showed inhibition activity of 53.9% at the same concentration. The fucan fraction from F. vesiculosus showed high inhibition activity of 98.1% on the reverse transcriptase enzyme of HIV-1 at 0.5 μg/mL concentration.251 Similarly, fractions of galactofucan from Adenocystis utricularis also presented anti-HIV-1 activity by blocking the prior events of virus replication. EA1-20 and EC2-20 displayed strong inhibition activity on HIV-1 replication at low IC50 values of 0.6 and 0.9 μg/mL, respectively.252 SPs are also produced by the microalgae. Naviculan is one such example that is isolated from Navicula directa that possesses anti-HIV-1 activity. It demonstrated inhibitory effect against the formation of cell–cell fusion between CD4-expressing HeLa cells and HIV gp160 at an IC50 value of 0.24 μM.253 A new type of D-galactan sulfate was isolated from Meretrix petechialis (clam) that possessed anti-HIV-1 activity by inhibiting syncytia formation at 200 μg/mL concentration with 56% inhibition.254 Laminaran (95), also termed laminarin, is a water-soluble polysaccharide including 20–25 glucose units possessing (1,3)-β-D-glucan with β(1,6) branching isolated from the brown algae. Laminaran (95) along with the laminaran polysaccharides prepared from kelp are known to inhibit the HIV reverse transcriptase and adsorption at a concentration of 50 μg/mL, suggesting good inhibition against HIV replication (Figure 33).255

Figure 33.

Structure of laminaran (95).

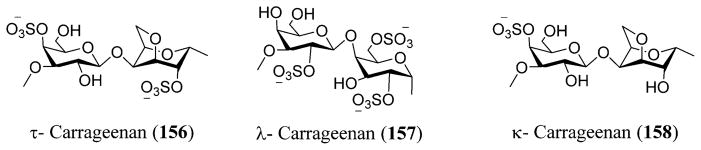

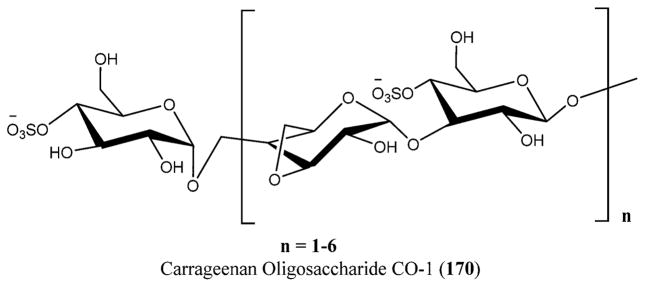

Galactan sulfate (GS), a polysaccharide isolated from Agardhiella tenera, a red seaweed, showed activity against HIV-1 and HIV-2 at IC50 values of 0.5 and 0.05 μg/L, respectively. GS prevents the binding of HIV-1 to cells along with the binding of anti-gp120 mAb to HIV-1 gp120. It is also known to be active against enveloped viruses including togaviruses, arenaviruses, herpesviruses, and others.256 Carrageenans are extracted mainly from certain genera of red seaweeds that include Hypnea, Eucheuma, Gigartina, and Chondrus. Yamada and co-workers reported anti-HIV activity for O-acylated carrageenan polysaccharides with various molecular weights by means of sulfation and depolymerization.257,258

Calcium spirulan (Ca-SP), a sulfated polysaccharide isolated from the marine blue–green alga Arthrospira platensis, showed potent anti-HIV-1 activity at an IC50 value of 2900 μg/mL and reduced viral replication at ED50 values of 11.4 and 2.3 μg/mL. Ca-SP is also known to inhibit the viral replication of other viruses that include HCMV, measles, polio, and coxsackie virus by preventing the penetration of the virus into the host cells.259 Xin et al. reported 911, a marine polysaccharide derived from alginate that inhibited the HIV replication both in vivo and in vitro, attributing to the inhibition of the viral reverse transcriptase, interfering with the viral adsorption, and enhancing immune function.260,261 Woo et al. reported the inhibitory effects of the marine shellfish polysaccharides from seven different shellfish, including Meretrix lusoria, Meretrix petechialis, Ruditapes philippinarum, Sinonovacula constricta Lamark, Scapharca subcrenata, Scapharca broughtonii, and Mytilus coruscus, against HIV-1 in vitro by inhibiting the viral fusion gp120/gp41 with the CD4 protein on the T-lymphocyte surface.262

SPs effectively inhibit the cell–cell adhesion.245 Studies proved that SPs could be used as antiviral vaginal formulations because they do not disturb the functions of the epithelial cells in the vagina or the normal bacterial flora.223,245

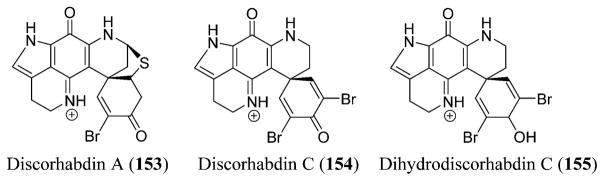

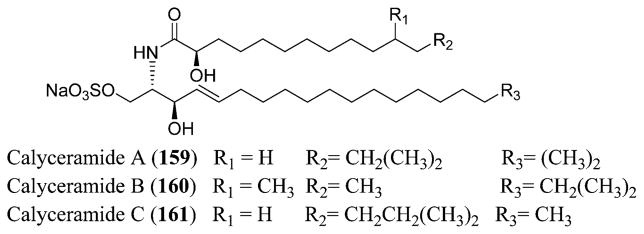

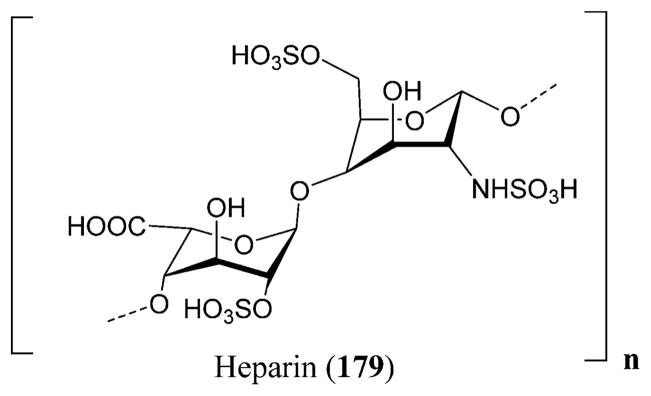

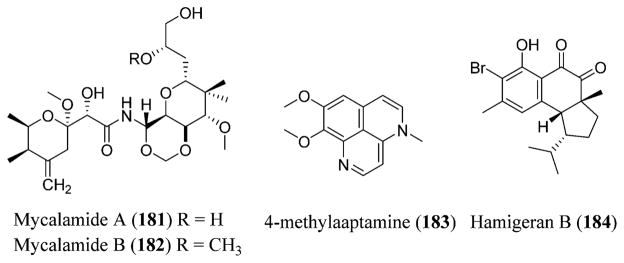

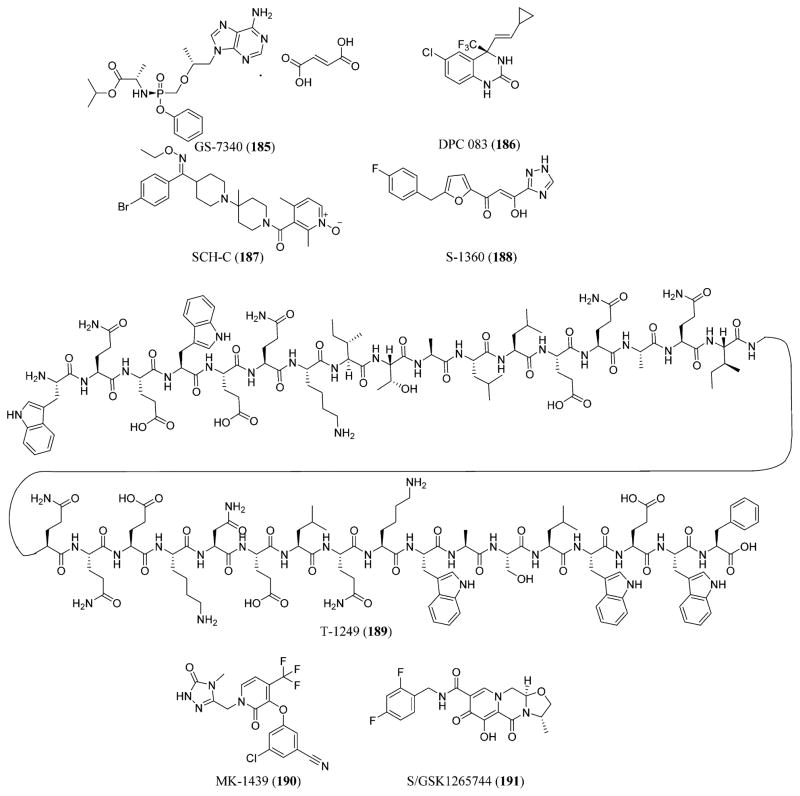

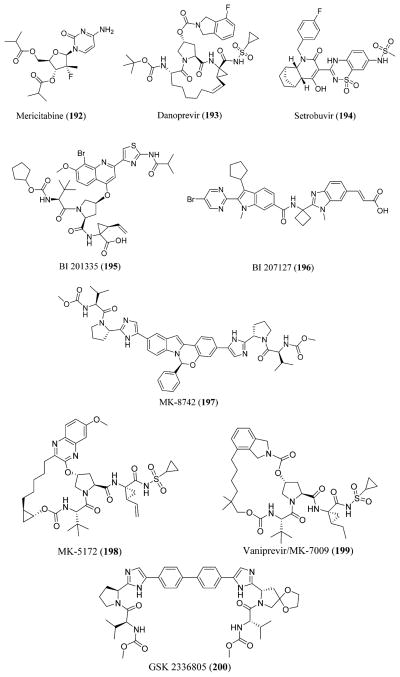

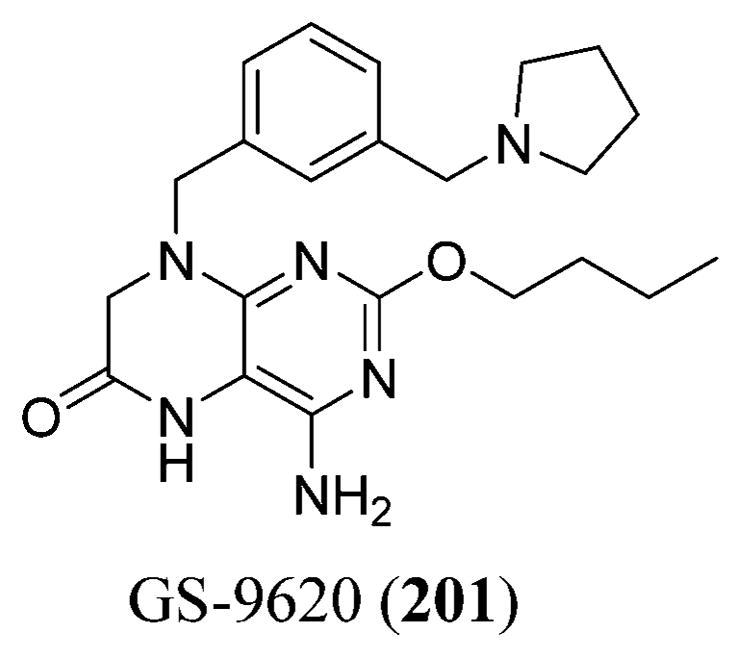

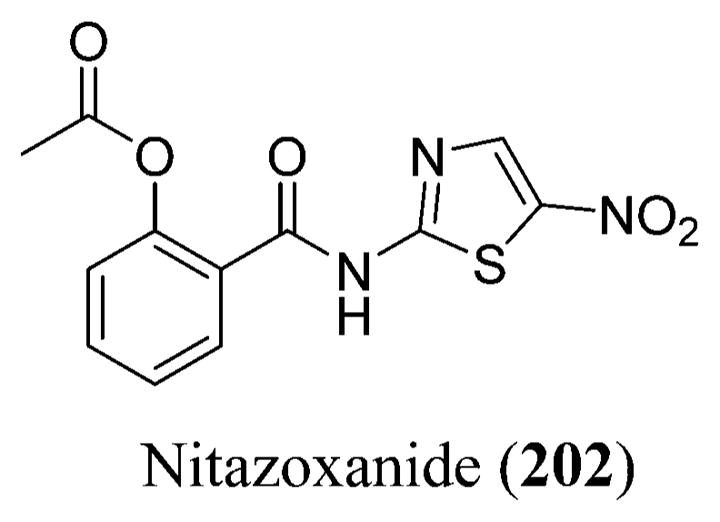

18.4. Lectins