Abstract

Background

Prescription opioids are the most rapidly growing category of abused substances, and result in significant morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs. Co-occurring with psychiatric disorders, persons with prescription opioid problems have negative treatment outcomes. Data are needed on the prevalence of co-occurring prescription opioid abuse and specific disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to better inform clinical practice. Objective: To determine prevalence rates of current co-occurring prescription opioid use problems and PTSD symptom severity among patients in community addiction treatment settings.

Methods

We abstracted administrative and chart information on 573 new admissions to three addictive treatment agencies during 2011. Systematic data were collected on PTSD symptoms, substance use, and patient demographics.

Results

Prescription opioid use was significantly associated with co-occurring PTSD symptom severity (OR: 1.42, p < 0.05). Use of prescription opioids in combination with sedatives (OR: 3.81, p < 0.01) or cocaine (OR: 2.24, p < 0.001) also were associated with PTSD severity. The odds of having co-occurring PTSD symptoms and prescription opioid use problem were nearly three times greater among females versus males (OR: 2.63, p < 0.001). Younger patients (18–34 years old) also were at higher risk (OR: 1.86, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Prescription opioid use problems are a risk factor for co-occurring PTSD symptom severity. Being female or younger increase the likelihood of this co-morbidity. Further research is needed to confirm these finding, particularly using more rigorous diagnostic procedures. These data suggest that patients with prescription opioid use problems should be carefully evaluated for PTSD symptoms.

Keywords: Co-occurring disorders, opioid use disorders, prescription opioid abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder

Introduction

Prescription opioid misuse constitutes the most rapidly growing substance-related problem in the United States (1–8). According to the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 5.3 million individuals aged 12 and older (2.1% of the general population) reported current nonmedical use of prescription opioids, such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. Furthermore, an estimated 1.9 million persons have prescription opioid dependence disorder (9). These escalating rates result in negative consequences, including morbidity, mortality and significant healthcare costs (2,3,5,7,10–15). The U.S. Centers for Disease Control determined prescription opioid overdose as the leading cause of accidental death (average of 40 people/day). This number exceeds motor vehicle accidents, and heroin and cocaine overdose combined (16,17). Certain demographic factors have been associated with prescription opioid use problems. Individuals of Caucasian race and the 18–25 year old subgroup have been found at increased risk (5,6,18–20). Data on gender as a risk factor is more equivocal (6,12,21). Several studies found similar rates of prescription opioid abuse for women and men (22–25), but a recent study found women at increased risk (26).

Clinical factors, including the use of other substances, have also been associated with increased prescription opioid abuse (2,8,21,23,27,28). Along with other substance use, co-occurring psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are correlated with prescription opioid abuse and related to poorer treatment and health outcomes (23,27–31). Treatment approaches for prescription opioid abuse were recently studied, but the moderating effects of psychiatric comorbidities on outcomes were not examined (32–34). Epidemiological and prospective longitudinal data are clearly needed to examine how psychiatric and other addictive disorders interact with prescription opioid abuse.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been found to co-occur with substance use disorders, and when co-morbid, results in more negative treatment outcomes (35–50). Research has found particularly high comorbidity between PTSD and opioid use disorders, relative to alcohol and other drugs (44,51,52). Women with rape histories have higher rates of prescription drug misuse (20), as do adolescents (12–17 years old) who have witnessed violence (5). Among Veterans, those with a PTSD diagnosis are significantly more likely to engage in high-risk use of prescription opioids, versus those without PTSD (53). A recent civilian study found a prevalence rate of 6.6% for comorbid PTSD and prescription opioid dependence. However, these were non-treatment seeking individuals recruited via advertisements. Therefore generalizability may be limited (54). To date, there are no published studies on the association between PTSD and prescription opioid use disorders within the civilian treatment seeking population.

The present study examined the prevalence of PTSD symptom severity among individuals with prescription opioid use problems (misuse, abuse or dependence) in three typical community addiction treatment programs.

This study provides data on the following research questions:

What is the prevalence of co-occurring PTSD symptoms among those with prescription opioid use problems, relative to other types of substance use problems?

Do certain demographic factors, such as gender and age, increase the risk for co-occurring PTSD symptoms and prescription opioid use problems?

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional design to evaluate the point prevalence of PTSD symptom severity among persons presenting for services to community addiction treatment agencies. PTSD severity was determined using a standardized self-report measure, the PTSD Checklist civilian version (PCL-C) (55–58). Substance use problem estimates were determined by systematic chart review. Three addiction treatment programs served as sampling sites, with data from each site treated independently in order to test for cross-site variation.

Settings

Admission data were obtained from three large adult community outpatient addiction treatment agencies located in southern, northern, and western cities in a single state (Vermont, USA).

Sample

Patients were seeking treatment for a substance use problem, which may or may not include opioid use disorders. At all three agencies, patients were assessed at intake using the PCL-C (described in the measures section below), and standardized assessments required by the state regulatory authority. There were no exclusion criteria with data from all new admissions gathered. Each program collected uniform data on patient demographics and substance use, including diagnoses and primary, secondary and tertiary substance use. Across all three programs, data from a total of 573 patients were collected, and these comprised the analytic sample.

Measures

PTSD symptom severity

The PTSD Checklist civilian version (PCL-C) is a 17-item, self-report measure with a 5-point scale (1 – Not at all, to 5 – Extremely bothered by PTSD-related symptoms linked to the most troublesome traumatic event). A total score of 44 or greater constitutes a probable PTSD diagnosis. The PCL psychometrics, including reliability, validity, sensitivity and specificity estimates have been reported (55–58). The PCL is commonly used and found to have predictive validity for determining PTSD diagnosis (59–70).

Substance use problems

Substance use problem data were extracted from patient charts. Specifically, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (71) was used to identify current primary, secondary, and tertiary substance use problems, as well as frequency and duration of use. The ASI has been used to derive and confirm substance use diagnoses in previous research (72). Prescription opioid use problems could include misuse, abuse or dependence.

Demographics

Gender, age, race and ethnicity data were extracted from the agencies' patient records based on their common federal requirements for the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) reporting.

Procedure

Patients completed the PCL-C at admission. Program staff with access to patient admission records gathered demographic information (gender, age, race and ethnicity), PCL-C scores, and primary, secondary and tertiary substance use problems for all patients admitted during a one-year time frame (2011) and linked these data with the self-report PCLs. Once information was compiled, program staff securely transmitted the de-identified data in aggregate to the research team. Because the archival information collected by program staff was de-identified, participant informed consent was not necessary. The study was conducted in strict accordance with all human subject protections and good clinical practices (e.g. Helsinki Declaration, Belmont Principles, and Nuremberg Code). The Trustees of Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) approved the collection, analysis and reporting of these data.

Data analysis

Patient demographic characteristics were analyzed initially by frequency analyses. To determine if having a prescription opioid use and/or other substance use problem was associated with PTSD symptom severity, a logistic regression was used. In contrast to frequency analyses with a Chi-square test, a simple logistic regression directly provides the odds ratio and confidence intervals. The dependent variable was PTSD severity (PCL ≥ 44) and the predictor variable was prescription opioid use problem. Both the outcome and predictor variables were dichotomous. We employed a multiple logistic regression to examine the predictive relationship between demographic variables (gender and age) and outcomes (PTSD severity; prescription opioid problem; and co-occurring PTSD symptom severity and prescription opioid use problems). Two statistical models were used (simple logistic regression and multiple logistic regression with covariates). There were eight simple logistic regressions and three multiple logistic regression in the analysis plan. Although this is not a large number of statistical tests, there is some risk for Type I error (false positives). Using a correction statistic (e.g. Bonferroni) to reduce this risk is a conservative option (73). However, doing so increases the risk for Type II error (false negatives) (74,75). To balance these risks, we conducted the tests without and with the correction. Significant findings are described in the Results section without the corrections, but interpreted in the conclusion more conservatively (i.e., p value ≤ 0.006). All data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS 21.0 statistical software package (76).

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the majority of patients were Caucasian (Not Hispanic or Latino) and between the ages of 26 and 34. More than half of the patients were male; the average PCL score was moderately high for the sample overall. Some 243 of 573 (42.4%) patients were above the symptom severity threshold (PCL ≥ 44), indicating probable PTSD diagnosis. The most frequent type of substance use problem was alcohol, followed by prescription opioids and cannabis. Most patients presented with poly-substance use.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics among patients admitted to addiction treatment.

| New Admissions (n = 573) | |

|---|---|

| Age m (sd) | 34.64 (11.72) |

| n (%) | |

| 18–25 | 154 (26.9%) |

| 26–34 | 186 (32.5%) |

| 35–50 | 164 (28.6%) |

| 51+ | 69 (12.0%) |

| Gender (Male) | 355 (62.0%) |

| Race (Caucasian/White) | 541 (96.3%) |

| Ethnicity (Not Hispanic or Latino) | 548 (98.9%) |

| m (sd) | |

| PCL score | 41.10 (17.66) |

| PTSD symptom severity: Moderate (44–64) | 52.60 (5.93) |

| PTSD symptom severity: Severe (65+) | 71.85 (5.53) |

| n (%) | |

| Total with PTSD symptom severity above diagnostic threshold (PCL ≥ 44) | 243 (42.4%) |

| Total with moderate PTSD symptom severity | 168 (23.0%) |

| Total with severe PTSD symptom severity | 75 (13.1%) |

| Primary substance use problem single substance only | |

| Alcohol | 118 (20.6%) |

| Cannabis | 11 (1.9%) |

| Cocaine | 3 (0.5%) |

| Heroin | 0 (0.0%) |

| Prescription opioids | 27 (4.7%) |

| Sedatives | 0 (0.0%) |

| Primary substance use problem in combination with other substances | |

| Alcohol | 353 (61.6%) |

| Cannabis | 200 (34.9%) |

| Cocaine | 159 (27.7%) |

| Heroin | 116 (20.2%) |

| Prescription opioids | 245 (42.8%) |

| Sedatives | 28 (4.9%) |

PTSD symptom severity and prescription opioid use problems

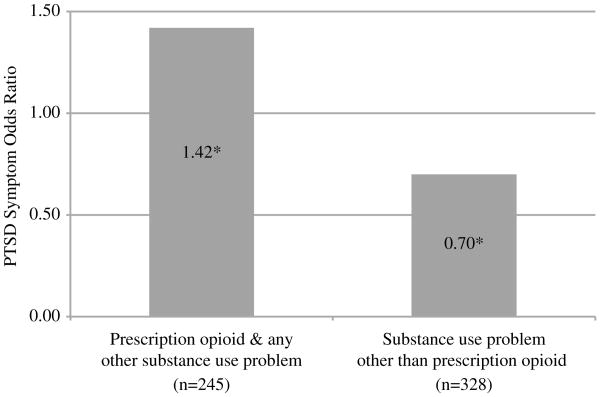

A total of 218 (38.0%) patients used prescription opioids along with other substances, while only 27 (4.7%) used prescription opioids exclusively. We collapsed these two variables into a combined “prescription opioids” variable for all subsequent analyses (n = 245 [42.8%]). A total of 47% of patients with a prescription opioid use problem had a probable PTSD diagnosis (PCL ≥ 44), while only 38.7% without a prescription opioid use problem likely met criteria for PTSD. A simple logistic regression was used to determine the likelihood for the co-morbidity. As shown in Figure 1, the odds of having severe PTSD symptoms was 1.42 times higher among patients with a prescription opioid use problem (CI: 1.02–1.99; p < 0.05). The odds of having severe PTSD symptoms were lower for patients who had a problem with a substance other than prescription opioids (CI: 0.50–0.98, p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity with and without a prescription opioid use problem (n = 573). Note: *p ≤ 0.05.

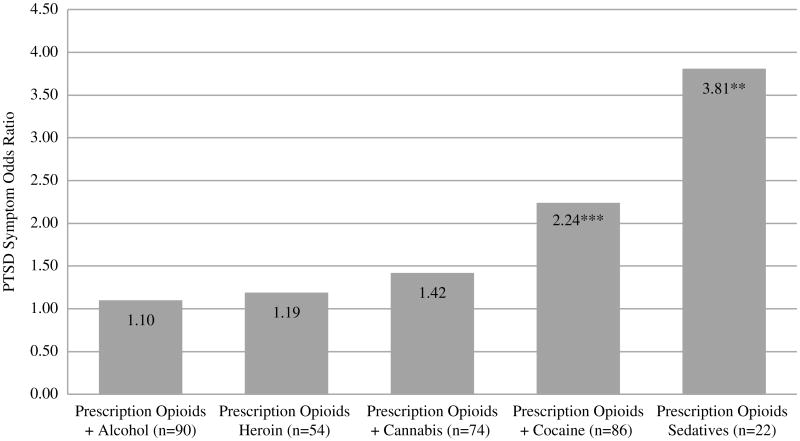

As shown in Figure 2, the odds of having severe PTSD symptoms was 3.81 times higher for patients with a prescription opioid and sedative use problem (CI: 1.47–9.88, p < 0.01). The odds of having PTSD for those with prescription opioid and cocaine use problems were 2.24 times higher (CI: 1.40–3.57, p ≤ 0.001). No significant associations between co-occurring PTSD symptom severity and the remaining possible poly-substance use combinations were revealed (prescription opioids + alcohol, prescription opioids + heroin, prescription opioids + cannabis).

Figure 2.

Odds ratios for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity by prescription opioid use problem in combination with other substances (n = 573). Note: **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; categories are not independent; the reference group was patients without a prescription opioid use problem and specific substance combination.

Demographic factors and risk for PTSD symptoms and prescription opioid use problems

Demographic variables, gender and age, were evaluated using multiple logistic regressions on PTSD severity or prescription opioid use problems (dichotomous variables). As shown in Table 2, females were at greater risk for prescription opioid use problems relative to males (OR: 1.81; CI: 1.27–2.59, p < 0.001). The odds of having severe PTSD symptoms were nearly three times greater for females (OR: 2.63; CI: 1.85–3.73, p < 0.001). Nearly a third (30.7%) of the female patient sample had co-occurring PTSD and prescription opioid use problems, while only 13.8% of the male sample had these co-occurring disorders. The odds of having both severe PTSD symptoms and a prescription opioid use problem were 2.64 times higher for females (CI: 1.73–4.02, p < 0.001). Age alone did not significantly predict PTSD severity or prescription opioid use problems. Overall model fit was evaluated by Chi-square tests, and showed that gender and age, collectively, had significant predictive power for the outcomes in all three models.

Table 2.

Predictive relationship between demographic variables (gender and age) and outcomes using multiple logistic regressions (n = 573).

| Outcomes | Gender + Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Predictor | OR | CI | χ2 | |

| PTSD symptom severity above diagnostic threshold (yes) | Gender | 2.63 | 1.86–3.73 | 30.30*** |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | ||

| † Prescription opioid (yes) | Gender | 1.81 | 1.27–2.59 | 64.45*** |

| Age | 0.95 | 0.93–0.96 | ||

| PTSD & Prescription opioid (yes) | Gender | 2.64 | 1.73–4.02 | 37.29*** |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.94–0.98 | ||

Prescription Opioid: Prescription opioid use problem alone or other substance use in combination with a prescription opioid use problem;

p ≤ 0.001.

Patients between the ages of 18–34 were 1.86 times the odds more likely than those 35 and older to have a co-occurring problem (prescription opioid use and severe PTSD symptoms (CI: 1.20–2.89, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Summary of findings

This is the first known study to examine the prevalence and risk factors for co-occurring PTSD symptoms and prescription opioid misuse among persons admitted to typical community addiction treatment settings. With regard to the first research question, the data revealed that prescription opioid use problems were associated with an increased risk for PTSD. The type of substances used in addition to prescription opioids, such as sedatives (medications including diazepam, alprazolam, or lorazepam) or cocaine, contributed to even greater risk. In addressing the second research question, two specific demographic factors, age and gender, emerged to compound the likelihood of comorbidity.

We found that for persons with prescription opioid use problems, compared with persons with other substance use problems, there was increased risk for severe PTSD symptoms. This is congruent with a recent study on non-treatment seeking individuals with opioid dependence (54). Results were consistent across the three community addiction treatment programs. Remarkable was the association of prescription opioid use and specific other substance use with PTSD symptom severity. The majority of those with prescription opioid use problems also used other substances. The odds of having severe PTSD symptoms were almost four times higher for persons with prescription opioid and sedative use problems, followed by prescription opioid and cocaine use problems. Prescription opioid use with cannabis, heroin, or alcohol did not demonstrate risk for PTSD.

With regard to demographic risk factors, gender was significant. Similar to recent research, females were more likely than males to have prescription opioid issues (6,12,21,22,24,25,77). Also consistent with previous research, females were more likely than males to have severe PTSD symptoms that meet the severity threshold for diagnosis regardless of type of substance use (36,51,78,79). Examining the co-occurrence of prescription opioid use problems and PTSD, females also had higher prevalence rates than males. There was a moderate association between age (18–34 year range) and the co-occurrence of PTSD symptoms and prescription opioid use problems. Thus, younger adults may be at increased risk.

Limitations

There were four limitations to this study, which can be summarized as follows:

Data gathered upon index admission were correlational and did not provide etiological information or the sequence of the problems. PTSD symptoms may be a risk factor for prescription opioid use problems. These symptoms could increase the misuse of, and consequential problems related to, prescription opioids (e.g. self-medicating to relieve PTSD symptoms). The alternative sequence is also possible: prescription opioid misuse may lead to an increase in exposure to traumatic events, such as interpersonal violence and motor vehicle accidents, and thereby increase the risk of developing PTSD. We could not test for this association. These limitations are inherent to cross-sectional designs and correlational statistics.

The archival data gathered across the three agencies were uniform and similarly gathered. However the substance use estimates relied on chart diagnoses and ASI summaries, which may have been less valid and scientifically rigorous than structured clinical interviews. The PCL is a commonly used assessment measure, but can be influenced by self-report response biases, and we did not itemize PTSD B, C and D criteria scores (re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyper-arousal). Standardized, clinician-administered measures would add to diagnostic certainty, and strengthen the interpretations of the findings.

Some caution must be exercised in the interpretation of the statistical findings due to Type I error. When applying a Bonferroni correction to these statistics all but one comparison retains statistical significance (p < 0.006). This comparison is the odds ratio (OR: 1.42) of prescription opioid problems and PTSD (p = 0.03). At increased risk for Type II error by dismissing this finding, a conservative interpretation would identify this relationship as a signal or trend. As with the other limitations to this investigation, a larger sample is needed to confirm these findings.

Finally, although a sample size of 573 patients was achieved, these were primarily Caucasian young adults (26–34 years old) seeking treatment. Although the primary outcomes were consistent across sites, a more diverse and broad sample from community treatment programs across more than one state would add to generalizability.

Clinical implications

These data suggest that community treatment patients with prescription opioid use problems should be carefully evaluated for trauma symptoms and a PTSD diagnosis. Since avoidance is a major feature of PTSD (80), the likelihood of patients under-reporting PTSD symptoms is high. During the early phases of abstinence, without anticipating the emergence of re-experiencing or hyperarousal symptoms, the patient may be at high risk for relapse. The use of opioids for the “self-medicating” purposes of “numbing” or anesthetizing negative affects has been well described (23,81,82). Integrated approaches that address both substance use and PTSD symptoms together and at the same time may be clinically optimal (38,43,83,84). There have been advances in medication assisted treatment options for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine (32–34). The evidence for integrated psychosocial therapies with these medications is mixed (33,85,86). However, integrated psychosocial treatments specifically designed for prescription opioid misuse and psychiatric disorders have not yet been studied.

The association between prescription opioid use problems and PTSD symptom severity may be further compounded by patient abuse of sedatives and/or cocaine. Combinations of substance use problems likely have important clinical implications for complexity and prognosis. Additionally, of the demographic factors examined, gender and age are associated with increased risk for the comorbidity, making it particularly important to screen females and young adults (18–34-year-olds) for the comorbidity.

Future research

Future research, including longitudinal repeated measures designs, broader and potentially more representative samples, and structured diagnostic assessments are needed to confirm the findings. Potential moderators between prescription opioid use problems and PTSD should also be addressed. These may include somatic and other psychiatric concerns that lead to seeking medical care for prescription opioids and/or sedatives. Chronic pain has been highly associated with PTSD (87–90), and those with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD (versus those without PTSD) have shown higher subjective pain ratings, more significant pain-related problems, and high rates of prescription opioid use for pain management, especially among women (25,91,92).

Opioid use disorder treatments have extensively focused on heroin, however persons with prescription opioid use type disorders may require different approaches than those abusing heroin (32–34,51). Given that rates of prescription opioid problems now surpass heroin, further opioid use disorder treatment research with these specific types of substances is warranted. With prevalence rates, risk factors, and moderators more clearly defined, pharmacological and psychosocial interventions targeting prescription opioid use disorders, and the most common psychiatric comorbidities, can be better designed and tested.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA R01 DA027650 (McGovern, PI). The authors would like to acknowledge Kurt White at Brattleboro Retreat, Jennifer Spagnuolo at Howard Center, and Clay Gilbert at Rutland Mental Health Center for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributions of authors: McGovern and Meier designed the study and wrote the protocol. An, Meier and McLeman managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Lambert-Harris and Xie performed the statistical analysis. Meier, Lambert-Harris and McGovern wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL. Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA. 2000;283:1710–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller NS. Prescription opiate medications: medical uses and consequences, laws and controls. Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2004;27:689–708. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2006;15:618–627. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Clinical J Pain. 2008;24:497–508. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCauley JL, Danielson CK, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Hanson RF, Smith DW, et al. The role of traumatic event history in non-medical use of prescription drugs among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleary SA, Heffer RW, McKyer EL. Dispositional, ecological and biological influences on adolescent tranquilizer, Ritalin, and narcotics misuse. J Adolescence. 2011;34:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales R, Brecht ML, Mooney L, Rawson RA. Prescription and over-the-counter drug treatment admissions to the California public treatment system. J Substance Abuse Treat. 2011;40:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller SC, Frankowski D. Prescription opioid use disorder: a complex clinical challenge. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administratiom (SAMHSA) Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manchikanti L. National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: facts and fallacies. Pain Physician. 2007;10:399–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, Kaplan JA, Kraner JC, Bixler D, Crosby AE, Paulozzi LJ. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300:2613–2620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. New Eng J Med. 2010;363:1981–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309:657–659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM. Increase in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the United States, 1999–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2009;22:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Minino AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;81:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore BA, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Chawarski MC, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. Primary care office-based buprenorphine treatment: comparison of heroin and prescription opioid dependent patients. J Gen Internal Med. 2007;22:527–530. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenblum A, Parrino M, Schnoll SH, Fong C, Maxwell C, Cleland CM, Magura S, Haddox JD. Prescription opioid abuse among enrollees into methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCauley JL, Amstadter AB, Danielson CK, Ruggiero KL, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Mental health and rape history in relation to non-medical use of prescription drugs in a national sample of women. Addictive Behav. 2009;34:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry DT, Goulet JL, Kerns RK, Becker WC, Gordon AJ, Justice AC, Fiellin DA. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and pain in veterans with and without HIV. Pain. 2011;152:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Concato J, Sullivan LE. Gender and non-medical use of prescriptiion opioids: results from a national US survey. Addiction. 2008;103:258–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellin DA. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Back SE, Payne RL, Simpson AN, Brady KT. Gender and prescription opioids: findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behav. 2010;35:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsells Kelly J, Cook SF, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA. Prevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult population. Pain. 2008;138:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHugh RK, Devito EE, Dodd D, Carroll KM, Potter JS, Greenfield SF, Connery HS, Weiss RD. Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. J Substance Abuse Treat. 2013;45:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang B, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Ruan WJ, Saha TD, Smith SM, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of nonmedical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1062–1073. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Blazer DG. How do prescription opioid users differ from users of heroin or other drugs in psychopathology: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Addiction Med. 2011;5:28–35. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181e0364e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conway KP, Compton WM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price AM, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Prevalence and correlates of nonmedical use of prescription opioids in patients seen in a residential drug and alcohol treatment program. J Substance Abuse Treat. 2011;41:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW, Bigelow GE. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:71–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Copersino ML, Prather K, Jacobs P, Provost S, Chim D, et al. Conducting clinical research with prescription opioid dependence: defining the population. Am J Addictions. 2010;19:141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, et al. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1238–1246. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Provost SE, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Hasson A, Lindblad R, et al. A multisite, two-phase, Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS): rationale, design, and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown PJ, Recupero PR, Stout R. PTSD substance abuse comorbidity and treatment utilization. Addictive Behav. 1995;20:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ouimette PC, Ahrens C, Moos RH, Finney JW. Posttraumatic stress disorder in substance abuse patients: relationship to 1-year posttreatment outcomes. Psychol Addictive Behav. 1997;11:34–47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouimette PC, Brown PJ, Najavits LM. Course and treatment of patients with both substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addictive Behav. 1998;23:785–795. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ouimette PC, Read JP, Wade M, Tirone V. Modeling associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and substance use. Addictive Behav. 2010;35:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Back SE, Dansky BS, Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Sonne S, Brady KT. Cocaine dependence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: a comparison of substance use, trauma history and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Addictions. 2000;9:51–62. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McKay JR, Rutherford MJ. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with substance use disorders: do not forget Axis II disorders. Psychiatric Annals. 2001;31:321–331. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1184–1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Direct Psychological Sci. 2004;13:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Shanahan M. The costs and outcomes of treatment for opioid dependence associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:940–945. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed PL, Anthony JC, Breslau N. Incidence of drug problems in young adults exposed to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: do early life experiences and predispositions matter? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1435–1442. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan TP, Holt LJ. PTSD symptom clusters are differentially related to substance use among community women exposed to intimate partner violence. J Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:173–180. doi: 10.1002/jts.20318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiMaggio C, Galea S, Li G. Substance use and misuse in the aftermath of terrorism. A Bayesian meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104:894–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop AE, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001-2010: implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dansky BS, Brady KT, Saladin ME, Killeen T, Becker S, Roitzsch J. Victimization and PTSD in individuals with substance use disorders: gender and racial differences. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22:75–93. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dore G, Mills K, Murray R, Teesson M, Farrugia P. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and suicidality in inpatients with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Review. 2012;31:294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mills KL, Lynskey M, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S. Post-traumatic stress disorder among people with heroin dependence in the Australian treatment outcome study (ATOS): prevalence and correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Peters L. Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:652–658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Krebs EE, Neylan TC. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307:940–947. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gros DF, Milanak ME, Brady KT, Back SE. Frequency and severity of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders in prescription opioid dependence. Am J Addictions. 2013;22:261–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. PTSD checklist – civilian version. Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD, Behavioral Science Division; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist-civilian version. J Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:495–502. doi: 10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. San Antonio, TX: 1993. The PTSD checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, Bush KR, McFall M, Epler AJ, Bradley KA. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in female Veteran's Affairs patients: validation of the PTSD checklist. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forbes D, Creamer M, Biddle D. The validity of the PTSD checklist as a measure of symptomatic change in combat-related PTSD. Behav Res Therapy. 2001;39:977–986. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grubaugh AL, Elhai JD, Cusack KJ, Wells C, Frueh BC. Screening for PTSD in public-sector mental health settings: the diagnostic utility of the PTSD checklist. Depression Anxiety. 2007;24:124–129. doi: 10.1002/da.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lang AJ, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Dresselhaus TR, Stein MB. Sensitivity and specificity of the PTSD checklist in detecting PTSD in female veterans in primary care. J Traumat Stress. 2003;16:257–264. doi: 10.1023/A:1023796007788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDonald SD, Calhoun PS. The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD checklist: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, Ford JD, Fox L, Carty P. Psychometric evaluation of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psycholog Assess. 2001;13:110–117. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Terhakopian A, Sinaii N, Engel CC, Schnurr PP, Hoge CW. Estimating population prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder: an example using the PTSD checklist. J Traumat Stress. 2008;21:290–300. doi: 10.1002/jts.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ventureyra VA, Yao SN, Cottraux J, Note I, De Mey-Guillard C. The validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Scale in posttraumatic stress disorder and nonclinical subjects. Psychother Psychosomat. 2002;71:47–53. doi: 10.1159/000049343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walker EA, Newman E, Dobie DJ, Ciechanowski P, Katon W. Validation of the PTSD checklist in an HMO sample of women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depression Anxiety. 2011;28:596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yeager DE, Magruder KM, Knapp RG, Nicholas JS, Frueh BC. Performance characteristics of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist and SPAN in Veterans Affairs primary care settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O'Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rikoon SH, Cacciola JS, Carise D, Alterman AI, McLellan AT. Predicting DSM-IV dependence diagnoses from Addiction Severity Index composite scores. J Substance Abuse Treat. 2006;31:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. Br J Med. 1995;310:170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Why we (usually) don't have to worry about multiple comparisons. J Res Educ. 2012;5:189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perneger TV. What's wrong with Bonferroni adjustments? BMJ. 1998;316:1236–1238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Green TC, Grimes Serrano JM, Licari A, Budman SH, Butler SF. Women who abuse prescription opioids: findings from the Addiction Severity Index-Multimedia Version Connect prescription opioid database. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Norris FH, Foster JD, Weisshaar DL. The epidemiology of sex differences in PTSD across developmental, societal, and research contexts. In: Kimerling R, Ouimette PC, Wolfe J, editors. Gender and PTSD. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psycholog Bull. 2006;132:959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hartwell KJ, Back SE, McRae-Clark AL, Shaftman SR, Brady KT. Motives for using: a comparison of prescription opioid, marijuana and cocaine dependent individuals. Addictive Behav. 2012;37:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown PJ, Stout RL, Mueller TI. Substance use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity: addiction and psychiatric treatment rates. Psychol Addictive Behav. 1999;13:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell AN, Hu MC, Miele GM, Cohen LR, Brigham GS, et al. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA's Clinical Trials Network. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:95–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. New Eng J Med. 2006;355:365–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Cutter CJ, Moore BA, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. Am J Med. 2013;126:74.e11–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schwartz AC, Bradley R, Penza KM, Sexton M, Jay D, Haggard PJ, Garlow SJ, Ressler KJ. Pain medication use among patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:136–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shipherd JC, Keyes M, Jovanovic T, Ready DJ, Baltzell D, Worley V, Gordon-Brown V, et al. Veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: what about comorbid chronic pain? J Rehabil Res Develop. 2007;44:153–166. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.06.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Asmundson GJ, Katz J. Understanding pain and posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity: do pathological responses to trauma alter the perception of pain? Pain. 2008;138:247–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Defrin R, Ginzburg K, Solomon Z, Polad E, Bloch M, Govezensky M, Schreiber S. Quantitative testing of pain perception in subjects with PTSD – implications for the mechanism of the coexistence between PTSD and chronic pain. Pain. 2008;138:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sansone RA, Mueller M, Mercer A, Wiederman MW. Childhood trauma and pain medication prescription in adulthood. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14:248–251. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2010.486901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Phifer J, Skelton K, Weiss T, Schwartz AC, Wingo A, Gillespie CF, Sands LA, et al. Pain symptomatology and pain medication use in civilian PTSD. Pain. 2011;152:2233–2240. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]