Summary

A plasmid, designated pMK, containing the structural gene for thymidine kinase from herpes simplex virus (HSV) fused to the promoter/regulatory region of the mouse metallothionein-I gene, was injected into the pronucleus of fertilized one-cell mouse eggs; the eggs were subsequently reimplanted into the oviducts of pseudopregnant mice. The first experiment produced 19 offspring, one of which expressed high levels of HSV thymidine kinase activity in the liver and kidney. pMK DNA sequences were detected in equal amounts in several tissues of the expressing mouse as well as in three mice that did not express HSV thymidine kinase activity. In all cases, several copies of the pMK plasmid were tandemly duplicated and integrated into mouse DNA. It appears as though multiple copies of the intact plasmid were fused by homologous recombination either before or after integration at a single site in the mouse genome. The overall efficiency of obtaining somatic expression of thymidine kinase in experiments performed to date is about 10% (4/41), and twice this number have integrated pMK DNA. This procedure not only provides a means of introducing new genes into mice, but it will also be a valuable system for studying tissue-specific regulation of gene expression.

Introduction

The recently developed techniques for introducing purified genes into cells via transfection or injection provide powerful tools for examining the DNA sequences required for normal gene expression and regulation. With appropriate vectors, these techniques are limited only by the availability of cell lines that can be propagated or by the sensitivity of the assays for gene expression. Using these techniques, investigators have introduced several eucaryotic genes into foreign cells, and their expression has been demonstrated at the nucleic acid level, protein level, or both (Mulligan et al., 1979; Wigler et al., 1979; DeRobertis and Olson, 1979; Capecchi, 1980; Grosschedl and Birnstiel, 1980; Lai et al., 1980). Furthermore, there are recent reports of regulation of gene expression in these systems (Kurtz, 1981; Buetti and Diggelmann, 1981; Hynes et al., 1981). For other genes, we anticipate that expression or regulation may be difficult to demonstrate because the appropriate cell type may not be amenable to analysis in culture, or developmental programming may be essential. To overcome these potential problems, it would be desirable to introduce genes into embryos and then to analyze gene expression in differentiated adult cells. Several approaches have been explored to achieve this goal.

One approach for introducing genes into animals has been to inject foreign cells, for example, teratocarcinoma cells, into mouse preimplantation blastocysts and then to reimplant them into pseudopregnant mice. In several cases this has resulted in phenotypic expression of the genes derived from the foreign cell in several tissues of the adult mouse, including the germ line (Brinster, 1974; Mintz and Illmensee, 1975; Papaioannou et al., 1975). Since these foreign cells can participate in the development of the adult, and because genes can be transfected or injected into cultured cells, the stage is set for introducing specific genes into animals. An important extension of this approach is to inject nuclei into enucleated mouse eggs, thereby assuring that the genetic traits of interest will be transmitted to the embryo (Illmensee and Hoppe, 1981).

We have microinjected plasmids directly into germinal vesicles of mouse oocytes or pronuclei of fertilized mouse ova (Brinster et al., 1981) and then implanted them into pseudopregnant mice. Gordon and coworkers (1980) have also used this technique to introduce plasmids containing the herpes thymidine kinase gene and SV40 sequences into mice. Two of 78 mice that they screened by Southern blot analysis were shown to have plasmid sequences; however, in both cases the plasmid DNA was not intact, and viral thymidine kinase activity was not detected. Here we report the successful application of this technique to the integration of a functional fusion gene into mice.

Results

Preparation of the Fusion Plasmid pMK

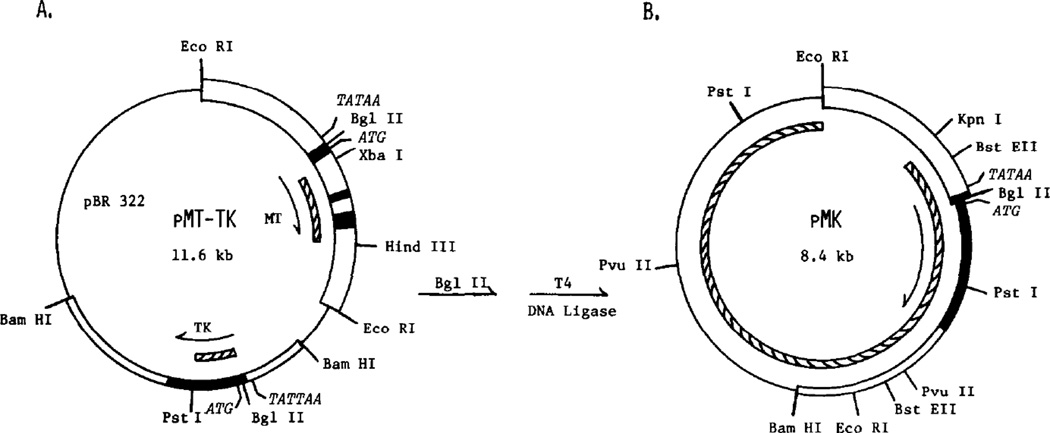

Preliminary experiments established that fusion of MT-I promoter/regulatory regions to the herpes thymidine kinase structural gene (HSV-TK) as shown in Figure 1 results in a gene, which we call MK, that can be expressed in mouse L cells and in mouse eggs. Furthermore, this gene is subject to regulation by heavy metals in a manner similar to the normal MT-I gene (K. Mayo, R. Warren and R. Palmiter; R. Brinster, H. Chen, R. Warren and R. Palmiter, submitted). This vector thus combines the advantages of a regulatable promoter and a simple enzyme assay to detect expression.

Figure 1. Structure of the Plasmids and DNA Fragments Used in this Study.

(A) Plasmid pMT-TK was constructed from plasmid m1pEE3.8 (Durnam et al.. 1980), which contains a 3.8 kb genomic Eco RI fragment that includes the MT-I gene inserted into the Eco RI site of pBR322, by insertion of the 3.5 kb Bam HI fragment of Herpes Simplex Virus Type I containing the thymidine kinase gene (McKnight, 1980) into the Bam HI site. The two genes are present in the same transcriptional orientation, as shown by the arrows.

(B) The fusion plasmid, pMK, was created by digestion of pMT-TK with Bgl II restriction endonuclease followed by ligation with T4 DNA ligase to directly join the 5′ region of the MT-I gene to the TK structural gene. pBR322 sequences are shown by a single line, TK gene sequences by a narrow box and MT-I gene sequences by a wide box. mRNA coding regions are represented by closed boxes; nontranscribed and intron regions are shown by open boxes. Hatched boxes inside the circles represent regions of these genes that ware used as hybridization probes; the MT-I specific probe, MT-XH, extends from Xba I to Hind III and TK-specific probe, TK-BP, extends from Bgl II to Pst I. The fusion plasmid probe, pMK(-EK), includes the entire plasmid except the Eco RI to Kpn I region because Southern blots revealed that this is a sequence present many times in the mouse genome. Restriction sites relevant to the construction of the plasmids and the gene-specific probes are shown in panel A. All restriction sites used in mapping integrated copies of pMK are shown in panel B. pMK is not cut by Hind III, Xba I or Xho I. Also shown are the locations of the TATAA promoter sequences and ATG translation start codons for the two genes.

Expression of Herpes Thymidine Kinase Activity in Mouse Liver

Approximately 200 copies of the plasmid, pMK, were injected into the male pronucleus of fertilized one-cell eggs; an average of 16 eggs then were transferred into the oviducts of 15 pseudopregnant mice. Six of these mice had litters, for a total of 12 male and 7 female offspring. At the age of 4 weeks each of the males was mated with a normal female. Before assaying for gene expression, the mice were injected with CdSO4 (2 mg/kg). This was done in the hope of inducing HSV-TK activity since this dose is known to induce MT-I mRNA in liver and kidney (Durnam and Palmiter, 1981). Eighteen hours later the mice were killed, liver samples were prepared for TK assay and the remainder of each animal was frozen for subsequent nucleic acid analysis.

For initial TK assay, 5 µl of a 20% liver homogenate was tested. One animal (23-2) showed about 40-fold more activity than the others did; however, this activity was so high that it was in the nonlinear range of the assay. After appropriate dilution we measured about 200-fold more TK activity in this mouse compared with litter mates and other mice of similar age (Table 1). To ascertain whether the TK activity was derived from the HSV-TK gene or from the endogenous mouse gene, an antibody specific for HSV-TK was mixed with the liver extracts prior to enzyme assay. Table 1 shows that the TK activity of mouse 23-2 was inhibited 97% with this antisera, whereas the TK activity of the other mice was essentially unaffected.

Table 1.

Herpes Thymidine Kinase and Mouse Metallothionein-I Gene Expression in Mouse Liver

| Mouse | pMK DNAa | Thymidine Kinase Activityb (cpm of 3H-TMP formed/mg wet wt/min) |

HSV-Thymidine Kinase mRNA (molecules/cell)c |

Mouse Metallothionein-I mRNA (molecules/cell) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −Ab | +Ab | ||||

| 14-1 | − | 355 | 261 | <2 | 2650 |

| 14-2 | − | 552 | 425 | <2 | 1330 |

| 19-1 | − | 593 | 723 | <2 | 1040 |

| 19-2 | ++ | 920 | 915 | 7.5 | 660 |

| 19-3 | − | 492 | 368 | <2 | 2760 |

| 21-1 | − | 656 | 525 | <2 | 1090 |

| 21-2 | − | 716 | 550 | <2 | 1480 |

| 21-3 | + | 468 | 579 | <2 | 610 |

| 21-4 | − | 770 | 654 | <2 | 770 |

| 21-5 | − | 633 | 571 | <2 | 1780 |

| 23-1 | + | 560 | 546 | <2 | 2420 |

| 23-2 | + | 23,475 (121,830) |

9,416 (4,141)d |

28 | 1500 |

The presence of pMK DNA in mouse tissue was determined by Southern blotting analysis as shown in Figure 2.

TK activity was measured as described under Experimental Procedures except that the samples were incubated with either 10 µl of anti-HSV-TK IgG fraction (+Ab) or normal IgG fraction (−Ab) for 15 min at 4° prior to the addition of the reagent mixture.

HSV-TK mRNA and mouse MT-I mRNA were determined as described in Experimental Procedures.

Values in parentheses were obtained when the homogenate from mouse 23-2 was diluted 10-fold prior to assay.

Additional assays confirmed that the majority of TK activity of mouse 23-2 was due to the HSV gene product. The endogenous mouse TK enzyme cannot phosphorylate iododeoxycytidine (IdC) whereas the HSV enzyme can (Summers and Summers, 1977). Thus, IdC will inhibit the conversion of 3H-thymidine to 3H-thymidylic acid if the enzyme is of viral origin. Table 2 shows that this is observed with the enzyme preparation from mouse 23-2, but not from the litter mates. The substrate specificity of the mouse and HSV-TK enzymes also can be demonstrated using 125IdC and tetrahydrouridine, an inhibiter of cytidine deaminase. In crude liver extracts from normal mice, 125IdC is converted into phosphorylated derivatives due to the action of deaminases that convert 125IdC to iododeoxyuridine which can be phosphorylated by TK. However, when an inhibitor of deaminase (tetrahydrouridine, THU) is included in the assay, labeled substrates for the endogenous TK enzyme are not formed and the apparent activity is inhibited 30-fold. In contrast, the TK activity in mouse 23-2 is inhibited only 20%, as would be expected with a viral enzyme that can utilize 125IdC directly (Summers and Summers, 1977).

Table 2.

Controls to Distinguish HSV-Thymidine Kinase Activity from Endogenous Thymidine Kinase

| Mouse | pMK DNA |

Thymidine Kinase Activity with 3H- thymidine as Substratea,b |

Thymidine Kinase Activity with 125IdC as Substrateb,c |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −IdC | +IdC | −THU | +THU | ||

| 23-2 | + | 497,000 | 187,000 | 71,300 | 56,400 |

| 23-1 | − | 14,500 | 14,700 | − | − |

| 14-1 | − | 7,520 | 9,640 | − | − |

| C57 × SJL | − | − | − | 150,400 | 4,800 |

Thymidine kinase was measured as described under Experimental Procedures, except that all of the samples contained tetrahydrouridine at 40 µM and half of the samples included 100 µM iododeoxycytidine (IdC) as indicated.

Data are the means of three determinations and they are expressed as cpm of product formed per assay.

Thymidine kinase activity was measured as described under Experimental Procedures except that 0.5 µCi of 125I-iododeoxycytidine at >700 Ci/mmole was substituted for 3H-thymidine; half of the samples included the cytidine deaminase inhibitor, tetrahydrouridine (THU), at a final concentration of 40 µM. The enzyme from mouse 23-2 was diluted to give an activity comparable to the control.

Detection of MK Genes in Several Mice

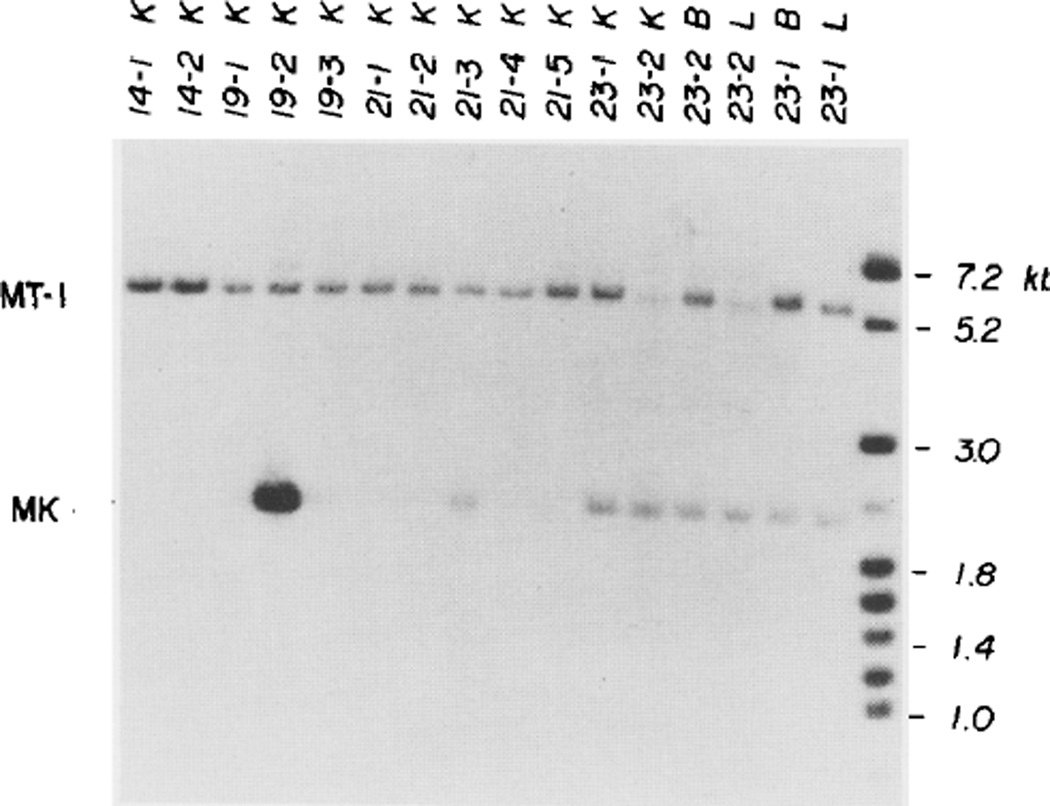

To assay for the presence of the MK fusion gene in the mice, kidney DNA was digested with restriction enzyme, Bst EII, subjected to electrophoresis on an agarose slab gel and blotted according to the method of Southern (1975). Nick-translated probes were used that would detect both the endogenous MT-I gene and any fusion gene. The endogenous MT-I gene falls within a 6 kb Bst EII fragment, whereas the MK fusion gene would be cut into a 2.3 kb fragment by this enzyme (see Figure 1B). Figure 2 shows that mouse 23-2 and three additional mice have the 2.3 kb band expected of the MK gene. The MK gene band has approximately half the intensity, as measured by densitometry, as the MT-I gene band in all of the mice except 19-2, in which the MK band is about six times more intense. To estimate the number of MK genes per cell, a control experiment was performed in which the same combination of probes was hybridized to equal molar amounts of the MT-I and MK genes. This was done by digesting pMT-TK (Figure 1A) with Eco RI or Pvu II and separating the MT-I gene and MK gene-containing fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis. Different amounts of the digests (40–160 pg of plasmid DNA) were analyzed by electrophoresis to facilitate quantitation. We observed that the autoradiographic band representing the MT-I gene was consistently 4-fold more intense than was the band representing the MK gene (data not shown). Since in our previous experiments the MT-I gene band was only twice as intense as was the MK gene band, we conclude that there must be twice as many MK genes per cell as MT-I genes. Thus, knowing that there are two MT-I genes per cell, we infer that there are four MK genes per cell in these mice. By use of the same calculation, we estimate that mouse 19-2 has about 48 copies of the MK gene per cell.

Figure 2. pMK Sequences Are Present in Four Mice.

DNA (6.5 µg) from the kidney (K) of each of the twelve mice, as well as DNA (6.5 µg) from liver (L) and brain (B) of mice 23-1 and 23-2, was digested with restriction endonuclease Bst EII (see Figure 1B), subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and hybridized to a mixture of MT-XH and TK-BP probes (see Figure 1A). The 6 kb band present in all samples represents the endogenous MT-I gene; the 2.3 kb band comigrates with the band generated by Bst EII digestion of pMK. We have noted a decreased intensity of the MT-I band in liver and kidney of mouse 23-2 in several experiments with these DNA preparations, but we cannot provide a satisfying explanation for this result.

Since HSV-TK enzyme activity was not detected in mice 19-2, 21-3 or 23-l even though intact MK genes were present (Table 1), we checked whether the mice were actually induced with Cd, by measuring the amount of MT-I mRNA by solution hybridization with 32P-labeled MT-I cDNA. Table 1 shows that all of the mice had between 600 and 2700 molecules of MT-I mRNA per liver cell. The basal level of MT-I mRNA in mouse liver is variable but averages about 150 molecules per cell, whereas after optimal induction, levels of about 2300 molecules per cell are generally obtained (Durnam and Palmiter, 1981). This control indicates that at the time the mice were killed the MT-I gene was still induced and suggests that the lack of thymidine kinase activity was not due to the failure of Cd delivery to the tissues.

We also measured HSV-TK mRNA levels by solution hybridization with a 32P-labeled HSV-TK cDNA. Although TK mRNA was detectable in the liver of mouse 23-2, the level was only 28 molecules per cell. A low amount of HSV-TK mRNA was also detected in mouse 19-2, the mouse with nearly 50 copies of the MK gene (Table 1). All other mice had less than two molecules of TK mRNA per cell.

Somatic Distribution of MK Gene and Thymidine Kinase Activity

Figures 2 and 3B show that the MK gene was present in several different tissues of mouse 23-2, including liver, kidney, brain, muscle and testis, and the intensity of the hybridizing band was similar in each tissue, suggesting that the gene copy number is constant in each tissue. HSV-TK activity and mRNA levels were lower in kidney than in liver and were undetectable in brain (Table 3). Thus, MK gene expression closely paralleled the MT-I gene expression in those tissues.

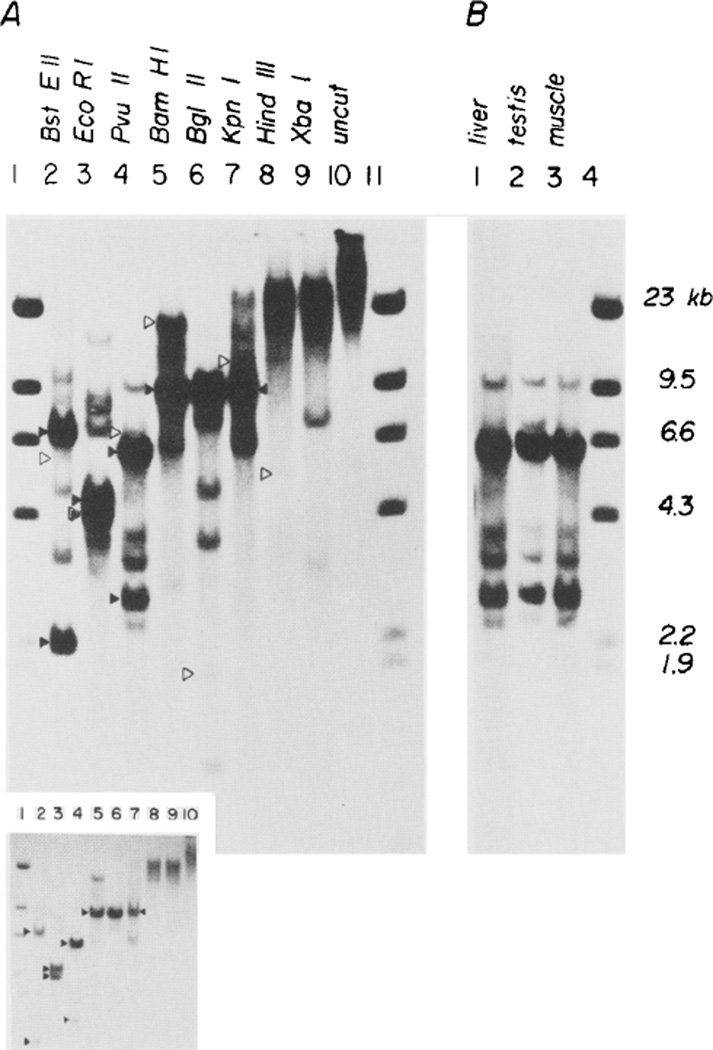

Figure 3. Junction Fragments and Tandem Repeats of pMK.

(A) Liver DNA (12 µg) from mouse 23-2 was digested with restriction enzymes that cut pMK twice (Bst EII, Eco RI, Pvu II), once (Bam HI, Bgl II, Kpn I), or not at all (Hind III, Xba I), subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and hybridized with a pMK(-EK) nick-translated probe (see Figure 1B). The inset at the bottom of A reveals the major bands more clearly; it was obtained after a 14 hr exposure compared to 60 hr for the main figure. Restriction fragments predicted from the endogenous MT-I gene (⊳) and from cleavage within the repeats of pMK (►) are indicated; the other bands are presumably junction fragments containing both pMK and mouse DNA.

(B) Comparison of Pvu II digests of liver, testis and muscle DNA (12 µg each) from mouse 23-2. Markers are a Hind III digest of phage λ.

Table 3.

Herpes Thymidine Kinase and Mouse Metallothionein-I Gene Expression in Several Mouse Tissues

| Thymidine Kinase Activityb (pmole TMP/min/mg protein) |

Thymidine Kinase mRNAC (molecules/cell) |

Metallothionein-I mRNAc (molecules/cell) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | pMK DNAa | Liver | Kidney | Brain | Liver | Kidney | Brain | Liver | Kidney | Brain |

| 19-2 | + | 1.37 | 1.44 | NDd | 7.5 | 3.4 | ND | 660 | 33.4 | ND |

| 21-1 | − | 1.98 | 1.74 | ND | <2 | <2 | ND | 1090 | 113 | ND |

| 21-2 | − | 1.89 | 2.26 | ND | <2 | <2 | ND | 1480 | 81.7 | ND |

| 21-3 | − | 1.12 | 1.78 | ND | <2 | <2 | ND | 610 | 183 | ND |

| 23-1 | + | 1.56 | 2.05 | 1.50 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 2420 | 81.2 | 7.2 |

| 23-2 | + | 66.8 | 4.44 | 1.23 | 28 | <2 | <2 | 1500 | 74.5 | 9.4 |

The presence of pMK DNA in mouse tissue was determined as in Figure 2.

TK enzyme activity was determined as described in Experimental Procedures. The assay buffer did not contain 5-iododeoxycytidine and therefore represents total enzyme activity.

TK mRNA and MT-I mRNA were determined as described in Experimental Procedures.

ND = not determined.

Integration of pMK into the Mouse Genome

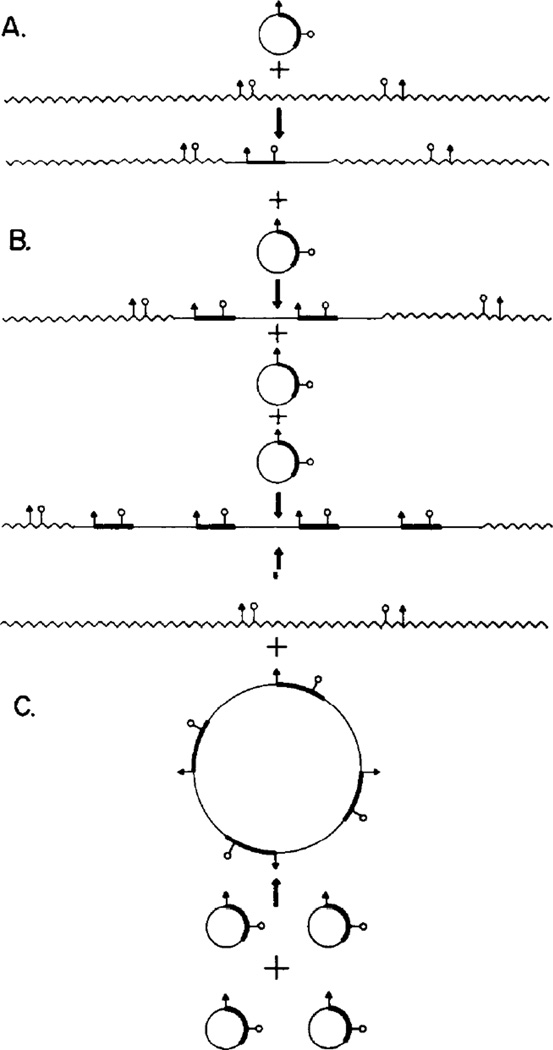

To ascertain whether the pMK plasmid was integrated into the mouse genome, DNA from each of the four mice positive for the MK gene was digested with several enzymes that cut twice, once, or not at all within the pMK plasmid. After electrophoresis and blotting, the nitrocellulose was hybridized with a nick-translated probe that included all of the plasmid except the 1150 bp between Eco RI and Kpn I; this region was omitted because it contains a repeat sequence. Predictions of what size bands would be produced are quite different depending on whether the pMK plasmid is integrated into the mouse genome or not. For example, with enzymes that cut once within a single integrated plasmid we would expect to generate only junction fragments, that is, fragments that combine both plasmid and genomic sequences, and they would be of a size different from that predicted from the plasmid (see Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Models for Integration of pMK DNA into Mouse DNA.

The plasmid is illustrated as a circular DNA molecule with two unique restriction sites shown symbolically ( ). (A) A single plasmid DNA molecule recombines (either by homologous or nonhomologous recombination) with mouse DNA to give a single integrated plasmid. The junction between mouse and plasmid sequences might occur at any site in both plasmid and mouse DNAs. Digestion with either of the two enzymes whose sites are shown would be expected to generate two products, neither of which would be likely to be the same size as linear pMK DNA.

). (A) A single plasmid DNA molecule recombines (either by homologous or nonhomologous recombination) with mouse DNA to give a single integrated plasmid. The junction between mouse and plasmid sequences might occur at any site in both plasmid and mouse DNAs. Digestion with either of the two enzymes whose sites are shown would be expected to generate two products, neither of which would be likely to be the same size as linear pMK DNA.

(B) After the initial integration event, a number of subsequent events could occur involving homologous recombination of additional copies of pMK into those already integrated, giving rise to a tandem repetition of the integrated pMK sequences. Digestion with either enzyme would generate several copies (three as drawn) of full-length linear pMK molecules, plus single copies of two new junction fragments.

(C) Several copies of the plasmid could homologously recombine with one another to generate a tandemly repetitive plasmid, which would then recombine with mouse DNA, again generating a tandemly repeated integrated plasmid. Restriction enzyme analysis would generate the same products as model B.

Restriction of liver DNA from each of the mice positive for MK genes with enzymes Bam HI, Bgl II or Kpn I, which cut only once within pMK, reveals a prominent 8.4 kb fragment that is the same size as that predicted from an unintegrated plasmid (Figure 3A and Figure 5). Likewise, enzymes that cut twice within pMK, such as Bst EII, Eco RI and Pvu II, give two prominent bands that add up to 8.4 kb, the size of pMK (Figure 3A). However, when enzymes were used that do not cut within pMK, such as Hind III and Xba I, the hybridizing DNA was nearly as large as uncut genomic DNA; no bands corresponding to unintegrated single plasmids were observed. A possible resolution of this paradox is that several copies of pMK are duplicated tandemly n times and integrated at a single site as indicated in Figures 4B and 4C. Restriction of DNA with this configuration would generate fragments corresponding to the original plasmid plus two junction fragments that would be less than 1/n as intense. Indeed, Figure 3 shows that in addition to the intense bands there are typically several additional fainter bands. One of these faint bands (marked with an open arrow) corresponds to the MT-I gene, which would be expected because about 650 bp of the probe are homologous to sequences 5’ of the MT-I gene (see Figure 1). The other faint bands (unmarked) are good candidates for the predicted junction fragments. The average intensity of the junction fragments from mouse 23-2 relative to the main band(s) is about 1/5, suggesting that the intact pMK plasmid is repeated about five times in this mouse.

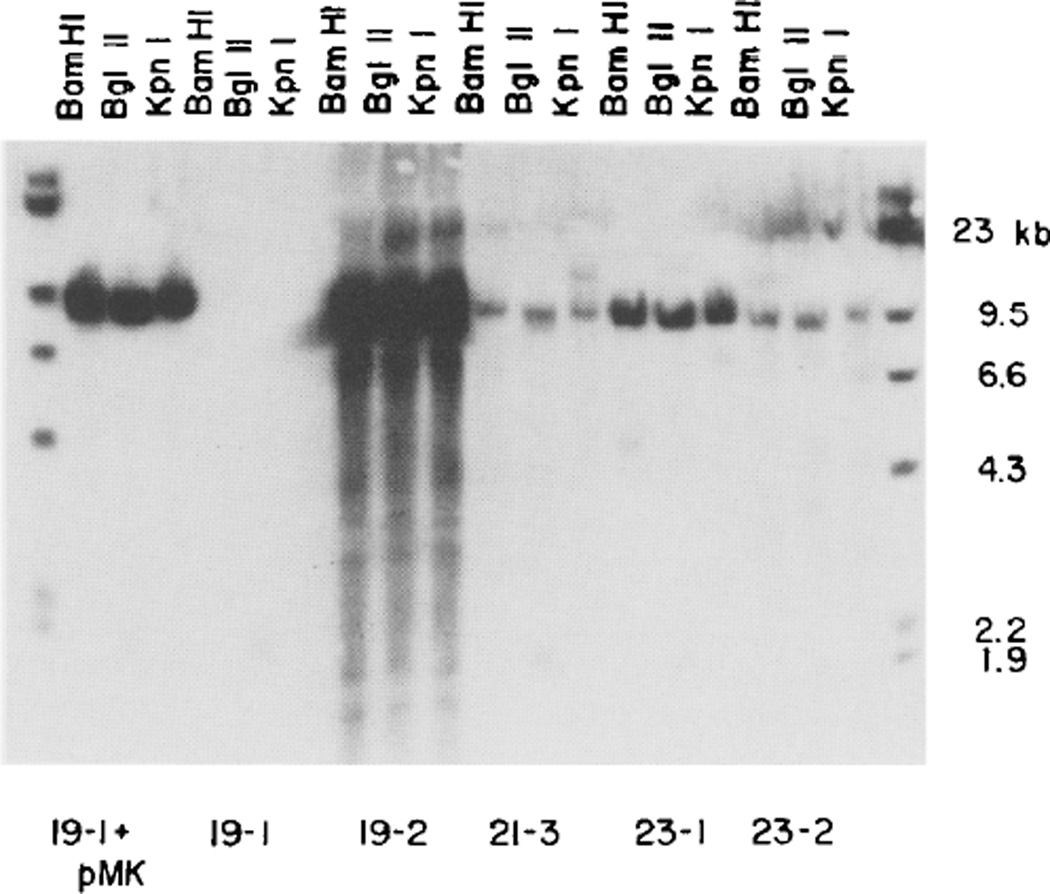

Figure 5. Junction Fragments and Tandem Repeats of pMK Are Present in All MK-Positive Mice.

Liver DNA (10 µg) of all four mice that contain pMK sequences (19-2, 21-3, 23-1, 23-2) and from a control mouse (19-l) was digested with Bam HI, Bgl II and Kpn I (each of these enzymes cuts pMK at a single site: see Figure 1B), subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to nitrocellulose and hybridized to pMK(-EK). Bands common to the 19-1 control and to the other mice come from the endogenous MT-I gene. The major band comigrates with linearized pMK. Additional bands that are presumed to be junction fragments are also observed.

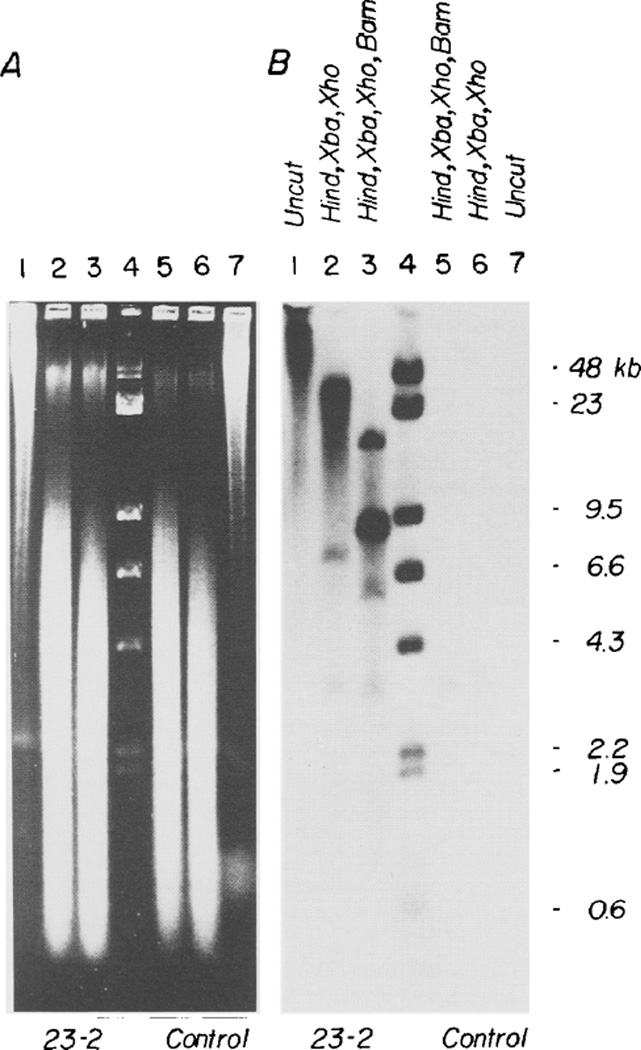

To test this idea of tandem duplication, we isolated high molecular weight DNA from mouse 23-2 and cut it with a battery of enzymes that do not cut within plasmid pMK; this procedure was an effort to cut the pMK repeat unit to a minimal size. Figure 6 shows that the size of the hybridizing band is greater than 45 kb (our largest marker) in uncut DNA and between 23 and 45 kb after restriction with Hind III, Xba I and Xho I, whereas total mouse DNA is cut to a weight average size of about 2 kb as shown by ethidium-bromide staining. When Bam HI was added along with the other enzymes, the 8.4 kb Bam HI linear fragment was obtained along with several fainter fragments that probably represent the predicted junction fragments. Thus, we conclude that there are four or five direct repeats of the pMK plasmid in mouse 23-2, a result that is consistent with the relative intensity of the 8.4 kb band and the junction fragments as well as gene dosage.

Figure 6. pMK Sequences Are Integrated into Cellular DNA.

DNA (16 µg) from the livers of mice 19-1 (control), 23-2, and 19-2 were subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.6% agarose gel without restriction nuclease digestion, after digestion with a mixture of Hind III, Xba I and Xho I (none of these enzymes cuts within pMK), or after digestion with the above enzymes plus Bam HI (which cuts pMK at a single site). (A) shows the ethidium bromide stained gel; (B) shows an autoradiogram after transfer to nitrocellulose and hybridization to a pMK(-EK) probe. The size markers are intact λ DNA and λ DNA digested with Hind III. The strong band seen after Bam HI digestion comigrates with pMK that has been similarly digested.

Inspection of Figure 3A reveals four junction fragments with most enzymes that cut within pMK (lanes 2 through 7) and one or two junction fragments with enzymes that do not cut within pMK (Figure 3A, lanes 8 and 9; Figure 6, lane 2). This suggests that in addition to the insertion of the major repeat of pMK, there may also be one or more integrated fragments of pMK in mouse 23-2, because integration at only a single site would have generated only two junction fragments with enzymes that cut within the plasmid and none with enzymes that do not.

Discussion

The data presented here demonstrate that we have achieved expression of HSV-TK in at least two tissues of a mouse derived from an injected egg. The HSV-TK enzyme activity, mRNA and gene were detected in both liver and kidney of mouse 23-2, whereas only the DNA was detected in the brain of this mouse. We used a fusion plasmid, pMK, that fuses the promoter/regulatory region of the mouse MT-I gene to the structural gene of the HSV-TK gene at the unique Bgl II site which lies a few nucleotides upstream of the initiation codons of both MT-I and HSV-TK genes (see Figure 1). This fusion plasmid can be regulated positively by heavy metals, such as Cd, when injected into mouse eggs or transfected into mouse L cells (R. Brinster, H. Chen, R. Warren and R. Palmiter; K. Mayo, R. Warren and R. Palmiter, submitted). In mouse eggs, the amount of TK activity obtained after exposure of injected eggs to Cd increases 10–20-fold depending on the dosage of pMK injected. Thus, we expected that the MT-I promoter would allow a high level of expression of HSV-TK. We assume that the MK gene is regulated by heavy metals in mouse 23-2 because the amount of TK activity in the liver of this mouse was about 100-fold higher than endogenous mouse TK activity. The tissue specificity of expression of the MK gene in mouse 23-2 is similar to that observed for the endogenous MT-I gene (Table 3) suggesting that the gene has been subject to some of the same developmental influences as the MT-I gene. In subsequent experiments the protocol has been changed so that the mouse is not killed for bioassay. Thus, we hope to be able to demonstrate regulation directly in future experiments.

The efficiency of achieving plasmid integration and expression in our first experiments is remarkably good. Nineteen offspring (12 males and 7 females) of the first experiment were assayed for TK expression and one, 23-2, was clearly positive. The DNA from the 12 males was assayed and four were positive. In a second experiment, the pMK plasmid was augmented by inserting the Bam HI fragment from Mulligan and Berg’s (1980) vector, pSV3-gpt, which contains the SV40 origin and T-antigen gene. Twelve offspring were analyzed for TK expression and pMK DNA and all were negative. In a third experiment, still in progress, the original plasmid was linearized and ligated to mouse DNA prior to injection. In this experiment, five offspring have now been analyzed, and two express HSV-TK and have the MK gene (see cover). In a fourth experiment, a linear 2.3 kb Bst E2 fragment that includes the MK gene was injected, and one out of five mice is positive for HSV-TK expression. The number of offspring is too low for good statistics and hence we do not know whether the variations in protocol are significant. Overall, out of 41 offspring that have been analyzed, we have obtained four mice that express HSV-TK and an additional three that have intact MK genes but do not express TK. We have decided to name the male mice that express the MK fusion gene MaK and the female mice MyK followed by a number denoting their foster mother. Thus mouse 23-2 will be designated MaK-23 in the future.

Analysis of the plasmid DNA from the four MK-positive mice described here suggests that the pMK plasmid is tandemly duplicated several times (Figure 5). If each plasmid were integrated separately, we would expect many junction fragments (fragments containing both PMK and mouse DNA sequences) when the DNA is restricted with an enzyme that cuts once within the pMK sequence. But instead, we observe predominantly the 8.4 kb fragment that represents the original plasmid (Figure 3). The best argument against freely replicating single plasmids is that the hybridizing band from uncut genomic DNA is much larger than the original plasmid (Figures 3 and 6). Thus, we conclude that in all cases the DNA must be duplicated tandemly as a direct repeat. The number of direct repeats is difficult to measure with certainty but it appears to be four or five in MaK-23 (Figure 6). These plasmid sequences must be linked physically to non-pMK sequences, since digestion with enzymes that do not cleave pMK nonetheless results in a significant reduction in the size of DNA band containing pMK (Figure 6). Further evidence that the set of direct repeats is integrated into genomic DNA is the existence of minor bands that may represent the junction fragments that are postulated if the DNA is integrated. The tandem duplication could occur by homologous recombination among the numerous pMK molecules injected, and it could occur either before or after the integration event as depicted in Figures 4B and 4C. Considering the fact that the egg is just completing meiosis and beginning the first mitotic division at the time of plasmid injection, the requisite enzymes for recombination may be abundant. Alternatively, oligomers of pMK that were present in the original plasmid preparation may be integrated preferentially. The presence of the pMK sequences in nearly equal abundance in all tissues that have been examined indicates stable inheritance of the pMK sequences during development, which is most easily explained by integration into the genome.

If the tandemly duplicated pMK plasmids are integrated, then an important parameter for determining the success of achieving expression is when the integration event occurs. The current view of mouse embryogenesis is that after the first four to six cleavages only the internal three to six cells are destined to become the embryo while the other outer cells develop into extraembryonic tissues. Thus, assuming that integration occurs only once, there is a considerable decrease in the probability of the plasmid DNA being represented in the embryo once cleavage begins. If the integration event occurs after the cells that are destined to become the embryo start to cleave, then the result would be a mosaic mouse.

We are exploring the question of whether the pMK sequences are in the germ line by analyzing offspring for pMK DNA or HSV-TK activity. Unfortunately the female to which MaK-23 was mated did not become pregnant. However one offspring (out of six) of MaK-67, the male on the cover, and one offspring (out of three) of MyK-84, a female from the fourth experiment described above, clearly express high levels of HSV-TK in the liver. Thus, in the two cases that have been analyzed to date, an expressible MK gene has been passed on to the second generation. In contrast, six offspring of mice 19-2 and 23-1, mice that contain pMK sequences but do not express HSV-TK, have no detectable pMK DNA sequences in their liver. Analysis of more mice will be necessary to determine whether this correlation between expression and transmission in the germ line is significant.

The basic approach described here provides a means of achieving expression of a gene in many, if not all, tissues of an animal. Although the average efficiency of achieving expression is only 10% so far, further refinements of the methodology may improve these statistics. There are several long-range benefits of this experimental approach for gene implantation. One is that a foreign gene can be introduced into any cell type. Another is that the influence of developmental history on gene commitment and gene expression can be assessed. Finally, this approach may provide a way to correct certain genetic defects.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmid Preparation

Plasmid pMK was constructed as shown in Figure 1. pMK DNA was isolated from a cleared lysate of bacterial cells by SDS-proteinase K treatment followed by phenol:chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The nucleic acids were digested with RNAase A and passed through Bio-Gel A50m column in 0.1 × SET (1 × SET = 1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) to separate DNA from RNA fragments. The preparation used for these experiments contained about 1/3 supercoiled plasmids, 1/3 nicked circles, and about 1/3 larger oligomers of the plasmid, as revealed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium-bromide staining.

Injection and Manipulation of Eggs

Fertilized one-cell ova of C57 × SJL hybrids were flushed from the oviduct using Brinster’s (1972) medium on the morning of day one of pregnancy. Cumulus cells were removed from ova with hyaluronidase (300 U/ml) and the ova were washed free of debris and enzyme before manipulation. For injection, the ova were transferred to a depression slide in Brinster’s medium containing 5 µg/ml cytochalasin B and were held in place by a blunt pipette while the tip of the injector pipette was inserted through the zona pellucida and vitellus and into the male pronucleus (Brinster et al., 1981). The DNA solution in the injector pipette was discharged slowly into the nucleus using a syringe connected to a micrometer. The larger pronucleus (male) of the fertilized ovum was injected with approximately 2 pl of plasmid solution. Following injection, the ova were washed free of cytochalasin and were returned to the same medium used for collection. When injections were completed, the ova were transferred to the oviducts of pseudopregnant, random-bred Swiss mice (Rafferty, 1970).

Thymidine Kinase Assay

Mouse tissues were homogenized in 4 vol of buffer containing 10 mM KCI, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM ATP, 10 mM NaF and 50 mM ε-aminocaproic acid (pH 7.4), and then centrifuged for 10 min at 15,000 × g (Kit et al., 1974). An aliquot (5 µl) was added to 25 µl of reaction mixture containing 150 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 10 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaF and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 5 µCi of 3H-thymidine (80 Ci/mmole; New England Nuclear). The mixture was incubated for 30 min or 2 hr at 37° and the 3H-TMP produced was measured by adsorption to DE-81 paper (Whatman) and subsequent scintillation counting. For specific activity measurements, protein was determined by the method of Bradford (1976).

Isolation of Nucleic Acid

Mouse tissues (liver, kidney, brain) were homogenized in 1 × SET buffer containing 50 µg/ml proteinase K (Beckman), incubated for 60 min at 45°, phenol:chloroform-extracted, ethanol-precipitated, and redissolved in 10 mM Tris-Cl, 0.25 mM EDTA (pH 7.5).

Metallothionein-I and Herpes Thymidine Kinase mRNA Determinations

MT-I mRNA levels were determined as described by Beach and Palmiter (1981). HSV-TK mRNA levels were determined similarly. The 840 bp Pst I-Pst I fragment that includes most of the structural HSV-TK gene (McKnight, 1980) was cloned into the Pst I site of fd 103 (Herrmann et al., 1980) and single-strand phage DNA containing the mRNA strand was prepared. 32P-cDNA was then prepared by nick translation of the 460 bp fragment extending from Bgl II site of HSV-TK to the Sst I site, and isolation of the cDNA strand by hybridization to the fd message strand and subsequent elution as described by Beach and Palmiter (1981).

Restriction Digestion, Gel Electrophoresis and Southern Blot Hybridization

Restriction enzymes (from Bethesda Research Labs and New England Biolabs) were used under standard conditions; RNAase A (Sigma; further treated by preincubation at 80° for 10 min) was added to all restriction digests at 50 µg/ml. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed on horizontal slabs in 80 mM sodium acetate, 40 mM Tris, 4 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). DNA was transferred to nitrocellulose essentially as described by Southern (1975). DNA probes were labeled by nick translation (Rigby et al., 1977) using α-32P-dNTPs (400–2000 Ci/mmole) purchased from Amersham and New England Nuclear. Hybridizations were at 45° in 50% formamide, 3.2 × SSC, 10% dextran sulfate for 12–16 hr (Wahl et al.. 1979). After hybridization, filters were washed in 2 × SSC plus 0.5 × SET at 68° followed by 0.5 × SET at 45°. Size markers are either phage λ DNA digested with Hind III and endlabeled, or a series of restriction fragments derived from the MT-I gene plasmid, m1pEE3.8 (Durnam et al., 1980).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Kit for antiserum against herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase. We are grateful to MS. A. Dudley for preparing this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Contributor Information

Ralph L. Brinster, Laboratory of Reproductive Physiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103

Howard Y. Chen, Laboratory of Reproductive Physiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103

Myrna Trumbauer, Laboratory of Reproductive Physiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103.

Allen W. Senear, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195

Raphael Warren, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195.

Richard D. Palmiter, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195

References

- Beach LR, Palmiter RD. Amplification of the metal-lothionein-I gene in cadmium-resistant mouse cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2110–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analyt. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL. Cultivation of the mammalian embryo. In: Rothblat G, Cristofala V, editors. Growth, Nutrition and Metabolism of Cells in Culture. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 251–286. [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL. The effect of cells transferred into the mouse blastocyst on subsequent development. J. Exp. Med. 1974;140:1049–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.4.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL, Chen HY, Trumbauer ME. Mouse oocytes transcribe injected Xenopus 5S RNA gene. Science. 1981;211:396–398. doi: 10.1126/science.7194505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buetti E, Diggelmann H. Cloned mouse mammary tumor virus DNA is biologically active in transfected mouse cells and its expression is stimulated by glucocorticoid hormones. Cell. 1981;23:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capecchi MR. High efficiency transformation by direct microinjection of DNA into cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1980;22:479–488. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRobertis EM, Olson MV. Transcription and processing of cloned yeast tyrosine tRNA genes microinjected into frog oocytes. Nature. 1979;278:137–143. doi: 10.1038/278137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durnam DM, Palmiter RD. Transcriptional regulation of the mouse metallothionein-I gene by heavy metals. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:5712–5716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durnam DM, Perrin F, Gannon F, Palmiter RD. Isolation and characterization of the mouse metallothionein-I gene. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:6511–6515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JW, Scangos GA, Plotkin DJ, Barbosa JA, Ruddle FH. Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:7380–7384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosschedl R, Birnstiel ML. Identification of regulatory sequences in the prelude sequences of an H2A histone gene by the study of specific deletion mutants in vivo. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:1432–1436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann R, Neugebauer K, Pirkl E, Zentgraf H, Schaller H. Conversion of bacteriophage fd into an efficient single-stranded DNA vector system. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1980;177:231–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00267434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes NE, Kennedy N, Rahmsdorf V, Groner B. Hormone-responsive expression of an endogenous proviral gene of mouse mammary tumor virus after molecular cloning and gene transfer into cultured cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2038–2042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illmensee K, Hoppe PC. Nuclear transplantation in Mus musculus: developmental potential of nuclei from preimplantation embryos. Cell. 1981;23:9–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kit S, Leung W-C, Trkula D, Jorgensen G. Gel electrophoresis and isoelectric focusing of mitochondrial and viral-induced thymidine kinases. Int. J. Cancer. 1974;13:203–218. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910130208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz DT. Hormonal inducibility of rat α20 globulin genes in transfected mouse cells. Nature. 1981;291:629–631. doi: 10.1038/291629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Woo SLC, Bordelon-Riser ME, Fraser TH, O’Malley BW. Ovalbumin is synthesized in mouse cells transformed with the natural chicken ovalbumin gene. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:244–248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight SL. The nucleotide sequence and transcript map of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Nucl. Acids Res. 1980;8:5949–5964. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.24.5949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B, Illmensee K. Normal genetically mosaic mice produced from malignant teratocarcinoma cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:3585–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan RC, Berg P. Expression of a bacterial gene in mammalian cells. Science. 1980;209:1422–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.6251549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan RC, Howard BH, Berg P. Synthesis of rabbit β-globin in cultured monkey kidney cells following infection with a SV40 β-globin recombinant genome. Nature. 1979;277:108–114. doi: 10.1038/277108a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou VE, McBurney MW, Gardner RL, Evans MJ. Fate of teratocarcinoma cells injected into early mouse embryos. Nature. 1975;258:70–73. doi: 10.1038/258070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty KA., Jr . Methods in Experimental Embryology of the Mouse. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby PWJ, Dieckmann M, Rhodes C, Berg P. Labeling deoxyribonucleic acid to high specific-activity in vitro by nick translation with DNA polymerase I. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;113:237–251. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern EM. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers WC, Summers WP. [125I]deoxycytidine used in a rapid, sensitive and specific assay for herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase. J. Virol. 1977;24:314–318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.24.1.314-318.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl GM, Stern M, Stark GR. Efficient transfer of large DNA fragments from agarose gels to diazobenzyloxymethyl-paper and rapid hybridization by using dextran sulfate. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:3683–3687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigler M, Sweet R, Sim GK, Weld B, Pellicer A, Lacy E, Maniatis T, Silverstein S, Axel R. Transformation of mammalian cells with genes from procaryotes and eucaryotes. Cell. 1979;16:777–785. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]