Abstract

Background

Merkel cell polyomavirus (PyV) is causally related to Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare skin malignancy. Little is known about the serostability of other PyVs over time, or associations with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Methods

As part of a US nested case-control study, antibody response against the PyV VP1 capsid proteins of BK and JC was measured using multiplex serology on 113 SCC cases and 229 gender, age, and study center-matched controls who had a prior keratinocyte cancer. Repeated serum samples from controls, and both pre- and post-diagnosis samples from a subset of SCC cases were also tested. Odds ratios (OR) for SCC associated with seropositivity to each PyV type were estimated using conditional logistic regression.

Results

Among controls, BK and JC seroreactivity was stable over time, with intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.86 for BK and 0.94 for JC. Among cases, there was little evidence of seroconversion following SCC diagnosis. JC seropositivity prior to diagnosis was associated with an elevated risk of SCC (OR=2.54, 95% CI: 1.23–5.25), and SCC risk increased with increasing quartiles of JC (P-for-trend=0.004) and BK (P-for-trend=0.02) seroreactivity.

Conclusions

PyV antibody levels were stable over time and following an SCC diagnosis. A history of PyV infection may be involved in the occurrence of SCC in a population at high risk for this malignancy.

Impact

A single measure of PyV seroreactivity appears a reliable indicator of long-term antibody status, and PyV exposure may be a risk factor for subsequent SCC.

Keywords: polyomavirus, skin cancer, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, nested case-control study, serology

INTRODUCTION

The human polyomavirus (PyV) is a non-enveloped virus with an icosahedral capsid containing a circular double-stranded DNA genome (1, 2). The genome of the Polyomaviridae family encodes three capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3), as well as small and large T antigens (TAg) (1, 3). The large TAg (LTAg) has oncogenic potential (1, 4, 5), but there is limited support for carcinogenesis in humans.

PyV infection rates vary between populations and viral types, and seroprevalence usually increases with age (6–11). Little is known about intraindividual PyV antibody stability over time in the general population (12), but repeated measures of PyV seroreactivity collected from individuals with a compromised immune system (13–20) suggest antibody levels may be consistent longitudinally.

PyV infections are ubiquitous within human populations (21). Among immunosuppressed patients, BK virus is the etiologic agent of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy and cystitis (22, 23), and John Cunningham virus (JC) reactivation has been linked to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (22, 23). Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) containing mutations in LTAg (24) has been established as a causal factor for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) – a rare but aggressive skin cancer (25–27).

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arises from epithelial keratinocytes (28), and is a common malignancy with increasing incidence rates reported in the United States (29–33). SCC etiology is largely attributed to ultraviolet radiation (34, 35), but other risk factors including immunosuppression (36–38) raise the possibility of a viral etiology. An oncogenic role for PyV infection in the development of SCC has been hypothesized in recent epidemiologic studies (39). A clinic-based case-control study from Florida, USA, found an increased SCC risk associated with antibodies against MCV assessed at the time of diagnosis (39). Conversely, a case-control study conducted among organ transplant recipients found no association between SCC development following transplant surgery and seropositivity to multiple PyV types prior to transplantation (40). There are limited prospective studies assessing whether past virus exposure predicts risk of future SCC development.

Therefore, using data and stored serum samples from patients with a prior history of keratinocyte cancer (KC) enlisted in a USA skin cancer prevention trial, we performed a longitudinal analysis of the presence and stability of antibodies against human PyV types BK and JC, and conducted a nested case-control study to investigate the role of polyomaviruses on subsequent SCC incidence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population and parent study design

We derived our study group from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study – a multicenter, randomized clinical trial conducted in the United States from 1980 to 1989 to test the efficacy of oral β-carotene supplementation in the prevention of KC among persons with a prior history of this malignancy (41, 42) (Supplemental Figure 1). The trial methods and study participants have been described in detail elsewhere (41–43). Briefly, patients were 35–<85 years of age and had had at least one biopsy-proven SCC or basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed since January 1, 1980. Of the 5,232 potentially eligible patients identified through a review of dermatopathology reports in the four clinical centers, 1,805 (34.5%) fulfilled the trial criteria, and were subsequently enrolled for randomization to receive either β-carotene or a placebo.

Upon entry to the trial, patients completed a questionnaire regarding individual characteristics, including age, hair and eye color, cigarette smoking, sun exposure, and medical history (e.g., vitamin use). A dermatological evaluation determined each patients’ skin type (i.e., tendency to sunburn, extent of solar damage), and the histological type and number of previous KC diagnoses was documented from patients’ medical records.

Follow-up consisted of an interval questionnaire mailed every 4 months. A dermatological examination was conducted at enrollment and annually thereafter, during which a 20 mL blood specimen was collected and stored in heparinized vacuum tubes at −75°C until analysis. The appearance of new, primary skin cancers was monitored, and microscopic slides of suspected cancerous lesions were re-reviewed by a dermatopathologist at the study coordinating center for independent validation. The primary trial end point was the first occurrence of a new basal or squamous cell carcinoma after randomization. Follow-up for each patient continued for 5 years or until September 30, 1989 when the treatment phase of the trial ended. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth.

Nested case-control study design

We conducted a nested case-control study within this intervention trial to examine the risk of subsequent incident SCC (i.e., the first new occurrence of a nonrecurrent squamous cell skin cancer following randomization) in relation to PyV infection status prior to diagnosis of this new SCC (hereafter referred to as the ‘prediagnostic’ or ‘prior to diagnosis’ time period) among patients with a history of KC. Of the 1,805 patients enrolled in the trial, 132 (7.3%) developed a new, nonrecurrent SCC during the follow-up period (hereafter referred to as a ‘case’). For each of these case patients, 2 controls were randomly selected from among patients who, up until or during the study year the SCC case was diagnosed, (a) had been actively followed, and (b) had not developed an incident and nonrecurrent SCC (hereafter referred to as a ‘control’). Controls were pair-matched to cases on gender, age (<45, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75–84 years), and study center (Hanover, NH; Minneapolis, MN; Los Angeles, CA; and San Francisco, CA). Controls were assigned a reference date corresponding to the case’s diagnosis date to whom they were matched.

We aimed to analyze the baseline (pre-randomization) serum sample for the determination of PyV seroreactivity for each case and control included in our study sample. If the baseline sample was unavailable, we tested the earliest blood sample collected – provided it was drawn prior to the diagnosis date for SCC cases or the reference date for controls.

Repeated measures

A subset of 89 cases had both a pre-diagnosis blood, and a post-diagnosis blood drawn nearest to, but following, the diagnosis date of the new SCC occurrence. We further investigated the stability of PyV antibodies over time in serial serum samples through a longitudinal serological study conducted among controls included in the nested case-control study. A total of 895 serum samples from 229 controls were available for serologic analysis. Control participant were included in this longitudinal sub-study if they had ≥2 serum samples collected during the follow up period of 6 years.

Human polyomavirus serology

Serum samples masked to case-control status were shipped on dry ice to the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ; Heidelberg, Germany) for analysis. Serum samples were assayed for antibodies against the immunodominant VP1 capsid protein (44) of two human-associated PyV types: BK (45) and JC (46). PyV seroreactivity was determined using a multiplex antibody detection approach based on a glutathione S-transferase (GST) capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method in combination with fluorescent bead technology (Luminex Corp., Austin, Texas, USA) (47, 48). Antigen preparation and techniques used for PyVs (39, 44, 49) closely follow methods applied to human papillomaviruses (HPV) as described previously (47, 50). Although the multiplex technology assayed for other viruses simultaneously (i.e., HPVs), BK and JC were the only PyVs included in the assay.

Seroreactivity against the PyV VP1 antigens was expressed as the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 100+ beads of the same internal color (48). MFI values reflect viral load (51), as well as antibody affinity, titer, and reactivity as determined by dilution series (52). Standard cut points to define seropositivity were chosen for each PyV by visual inspection of frequency distribution curves (percentile plots) for the inflection points of all sera tested, as done in prior studies (27, 49, 50, 53). The standard cutoff value for VP1 seropositivity was 400 MFI units. To evaluate the robustness of PyV VP1 seroprevalence and odds ratio (OR) estimates for SCC by PyV seropositivity, we used a sliding cut point between 250 and 550 MFI units. We ultimately used the standard cut points in all analyses as PyV seroprevalence (Supplemental Figure 2) and OR estimates (from conditional and unconditional logistic regression models; Supplemental Figures 3– 4) were insensitive to cut point definition.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.1.0. All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance assessed at the α=0.05 level. Individual characteristics of SCC cases and controls were compared using the X2 test (for categorical variables, i.e., gender, randomization arm, study center, previous skin cancers, cigarette use, skin sun sensitivity, occupational sun exposure, eye color, hair color, vitamin use) or Fisher’s exact test (for categorical variables with small strata containing ≤10 persons, i.e., BMI category, extent of UV skin damage, sun bathing), and Wilcoxon rank sum test (for continuous variables, i.e., age). Among controls, the seroprevalence of each PyV type was examined for both PyV seropositivity overall, and by age groups, using binary MFI cut points. Additionally, we tested the association between various individual characteristics in relation to PyV seropositivity within controls. We used the continuous MFI values from controls to compute Spearman rank correlation coefficients (ρ) between both PyVs assayed.

Within controls, we investigated intraindividual changes in PyV seroreactivity over time using repeated measures taken after baseline by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (54) for continuous MFI values, and also stratified analyses by randomization arm of the original trial (i.e., treatment or placebo). Additionally, to determine serostatus (positive versus negative) stability over time, we defined control participants as being seropositive at all time points (stably seropositive), seronegative at all time points (stably seronegative), seroconverting (change from seronegative to seropositive over time), seroreverting (change from seropositive to seronegative), or fluctuating between seropositive and seronegative (fluctuating), as has been done previously (12, 13, 55). The likelihood of seroconversion following SCC diagnosis was evaluated with the kappa (κ) statistic among cases (56–58).

We used both conditional (as there was one-to-two pair-matching between cases and controls in the original trial) and unconditional logistic regression (while adjusting for the matching factors: age, gender, and study center) to calculate the ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the development of a new SCC by VP1 seropositivity compared to seronegativity for each PyV type in the baseline or earliest blood sample collected. Quartiles of seroreactivity based on the control distributions of continuous MFI values was created for each PyV, and associated with SCC by comparing the second, third, and fourth quartiles to the first (lowest) quartile in conditional and unconditional logistic regression models. Tests-for-trend were conducted by including an ordinal variable in the logistic model in place of the categorical quartile variable. Using the study sample for unconditional models, generalized additive logistic models (GAM) were fit to evaluate deviations from linearity in risk of SCC by the continuous MFI values from the earliest blood samples (59, 60). The smoothed (nonparametric) component of the binomial GAMs was PyV seroreactivity, and adjustment was made for the unsmoothed matching factors. Models were not further adjusted for potentially confounding covariates, as no sociodemographic or individual characteristic was found to both be associated with PyV serostatus and a risk factor for SCC development in our study group. We assessed the potential modifying effects of the assigned randomization arm from the original trial, having had a prior SCC, and having had a prior BCC in stratified analyses. We also performed stratified analyses by smoking status, UV skin damage, skin sun sensitivity, and hair color.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

We tested a prediagnostic serum sample for 113 (85.6%) of the 132 SCC cases, and 229 (86.7%) of the 264 controls, for the nested case-control study. Pair-matched sets with at least one measured control directly matched to a case consisted of 111 (84.1%) SCC cases and 195 (73.9%) controls. Tested serum samples for all 342 study participants were drawn by the first year after baseline on 93.3% of both cases and controls, and samples were taken 15 days to 5.3 years before the diagnosis or reference date (median=2.2 years, interquartile range (IQR)=1.3–3.3 years). Among 210 controls (excluding 19 controls who only had a single sample collected), we performed repeated serologic analysis on 876 (97.9%) of the 895 serum samples drawn during the follow-up period for the longitudinal study. Controls had 2 to 8 serial samples with a median of 4 samples per participant, taken 11 days to 4.2 years apart (median number of years between repeated measures=1.0 years, IQR=1.0–1.1 years). We analyzed 85 (95.5%) of the subset of 89 SCC cases with both pre- and post-diagnosis serum samples, and the post-diagnostic samples were obtained 17 days to 1.7 years following the diagnosis date (median=0.7 years, IQR=0.6–0.7 years).

Participants in this study ranged in age from 35 to 84 years (median age of 67 years) upon study entry, and 88.1% were men. Cases and controls were balanced with respect to age, gender, and study center through the matched design. Compared to controls, SCC cases were more likely to have had ≥2 previous KCs, be current or former cigarette smokers, have skin that always or usually burned with sun exposure, be blonde or red-haired, and have moderate to severe actinic damage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of selected baseline characteristics among cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cases and controls from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study (n=342).a

| Characteristic | SCC Cases (n=113), No. (%) |

Controls (n=229), No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 100 (88.5) | 201 (87.8) |

| Female | 13 (11.5) | 28 (12.2) |

| Median age, SD (years) | 68 (8.0) | 67 (8.2) |

| Randomization arm in RCT | ||

| Treatment | 66 (58.4) | 115 (50.2) |

| Placebo | 47 (41.6) | 114 (49.8) |

| Study centerb | ||

| DHMC | 24 (21.2) | 43 (18.8) |

| UCLA | 32 (28.3) | 65 (28.4) |

| UCSF | 25 (22.1) | 56 (24.4) |

| UMN | 32 (28.3) | 65 (28.4) |

| Previous skin cancers | ||

| 1 | 24 (21.2) | 102 (44.5)*** |

| 2 | 21 (18.6) | 41 (17.9) |

| 3 | 12 (10.6) | 20 (8.7) |

| 4–5 | 26 (23.0) | 36 (15.7) |

| 6–9 | 12 (10.6) | 17 (7.4) |

| ≥10 | 18 (15.9) | 11 (4.8) |

| Cigarette use | ||

| Never smoked | 28 (24.8) | 91 (39.7)** |

| Former smoker | 62 (54.9) | 111 (48.5) |

| Current smoker | 23 (20.3) | 27 (11.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| Underweight <18.5 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Normal 18.5–24.9 | 50 (44.2) | 98 (42.8) |

| Overweight 45.0–29.9 | 47 (41.6) | 108 (47.2) |

| Obese >30.0 | 12 (10.6) | 15 (6.6) |

| Skin sun sensitivity | ||

| Always or usually burns | 72 (63.7) | 110 (48.0)** |

| Burns moderately or minimally | 41 (36.3) | 118 (51.5) |

| Extent of UV skin damage | ||

| Mild | 9 (8.0) | 62 (27.1)*** |

| Moderate | 71 (62.8) | 134 (58.5) |

| Severe | 32 (28.3) | 31 (13.5) |

| Sun bathed (hours) | ||

| Never | 40 (35.4) | 62 (27.1) |

| 0–200 | 18 (15.9) | 63 (27.5) |

| 200–400 | 25 (22.1) | 54 (23.6) |

| 400–600 | 21 (18.6) | 33 (14.4) |

| >600 | 7 (6.2) | 17 (7.4) |

| Occupational sun exposure (years) | ||

| 0–7 | 41 (36.3) | 78 (34.1) |

| 7–20 | 31 (27.4) | 64 (27.9) |

| 21–40 | 28 (24.8) | 40 (17.5) |

| >40 | 13 (11.5) | 46 (20.1) |

| Eye color | ||

| Blue, green, gray, hazel | 97 (85.8) | 185 (80.8) |

| Brown, black | 16 (14.2) | 44 (19.2) |

| Hair color | ||

| Blonde, red | 49 (43.4) | 61 (26.6)** |

| Brown, black | 64 (56.6) | 64 (27.9) |

| Vitamin use | ||

| No | 67 (59.3) | 128 (55.9) |

| Occasional | 15 (13.3) | 37 (16.2) |

| Daily | 24 (21.2) | 60 (26.2) |

P< 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001. P values obtained from X2, Fisher’s exact, or Wilcoxon rank sum test (as appropriate) comparing sociodemographic and skin cancer risk factors between SCC cases and controls.

Numbers may not sum to the overall total due to missing data.

This multicenter study was conducted at sites in California (University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine (UCLA); University of California Medical School, San Francisco (UCSF)), Minnesota (University of Minnesota Schools of Medicine and Public Health, Minneapolis (UMN)), and New Hampshire (Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Hanover (DHMC)), USA.

BK and JC antibody status over time among controls

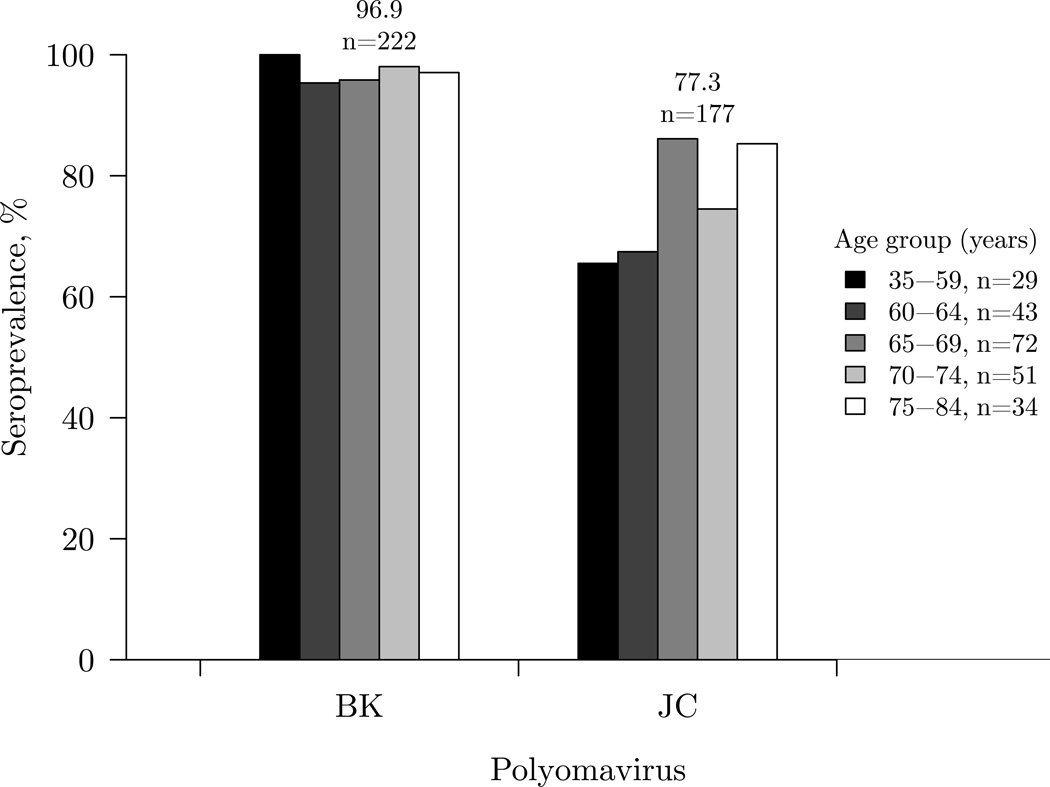

Among the baseline or first measured samples in controls, the overall seroprevalence was 96.9% for BK and 77.3% for JC (Figure 1). Seroprevalence was constant across age groups for BK, and increased with age group for JC (P-for-trend=0.02). Sociodemographic and individual characteristics at study entry were not related to BK or JC serostatus (Supplemental Table 1). We did not find correlations or evidence of cross-reactivity between the VP1 capsid proteins of BK and JC for the earliest prediagnostic samples collected (ρ=0.06, P=0.09) or for the repeated measures (ρ=0.06, P=0.07).

Figure 1.

Seroprevalences of human polyomaviruses (PyV) as determined by VP1 seroreactivity among 229 controls by age group from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study, using the baseline or earliest serum sample collected. The overall seroprevalence (%) and number of participants who were seropositive for each PyV is shown above the bars. The number of participants within each age group is noted in the legend.

BK and JC seroreactivity remained stable over time within controls in the repeated serum measures (Table 2). The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.86 for BK and 0.94 for JC, and no difference was found in ICC estimates when stratified by randomization arm of the original trial. For BK, 95.7% were stably seropositive, and 2.9% remained seronegative. There were no seroreversions, and <1% seroconverted (0.9%) or had fluctuating antibody levels (0.5%). For JC, 74.8% were stably seropositive, and 20.9% remained seronegative; 2.9% seroconverted, 0.9% seroreverted, and 0.5% had fluctuating antibody levels.

Table 2.

Serostability for BK and JC human polyomavirus (PyV) seropositivitya in samples collected longitudinally over time among 210b controls from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study.

| PyV | Controls Serostability (n=210), No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stably seropositive | Stably seronegative | Seroconversion | Seroreversion | Fluctuating | |

| BK | 201 (95.7) | 6 (2.9) | 2 (0.9) | None | 1 (0.5) |

| JC | 157 (74.8) | 44 (20.9) | 6 (2.9) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) |

PyV infection was determined using seropositivity for the VP1 protein.

Not including 19 controls who only had a single sample collected. Only controls with ≥2 repeated serum samples were included.

Pre- versus post-diagnostic BK and JC serostatus

We compared PyV serostatus prior to and closely following the first occurrence of an incident SCC diagnosis among a subset of SCC cases (Table 3). One (1.2%) case who was BK seronegative prior to diagnosis remained seronegative following SCC diagnosis, and 84 (98.8%) cases who were seropositive prior to diagnosis remained so following diagnosis. For JC, we found 10 (11.8%) cases to remain seronegative, and 74 (87.1%) cases to remain seropositive, prior to and following diagnosis; only 1 (1.2%) case who was seronegative seroconverted to JC seropositive following SCC diagnosis. As a measure of agreement, the kappa statistic (κ) was close to 1 for both BK (κ=1.0, 95% CI: 0.79–1.0) and JC (κ=0.95, 95% CI: 0.73–1.0).

Table 3.

BK and JC human polyomavirus (PyV) serostatusa prior to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis (SCC), and post SCC diagnosis, among 85 cases from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study.

| PyV serostatus pre-diagnosis |

PyV serostatus post-diagnosis (n=85) | |

|---|---|---|

| Seronegative, No. (%) |

Seropositive, No. (%) |

|

| BK | ||

| Never seropositive | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) |

| Ever seropositive | 0 (0) | 84 (98.8) |

| JC | ||

| Never seropositive | 10 (11.8) | 1 (1.2) |

| Ever seropositive | 0 (0) | 74 (87.1) |

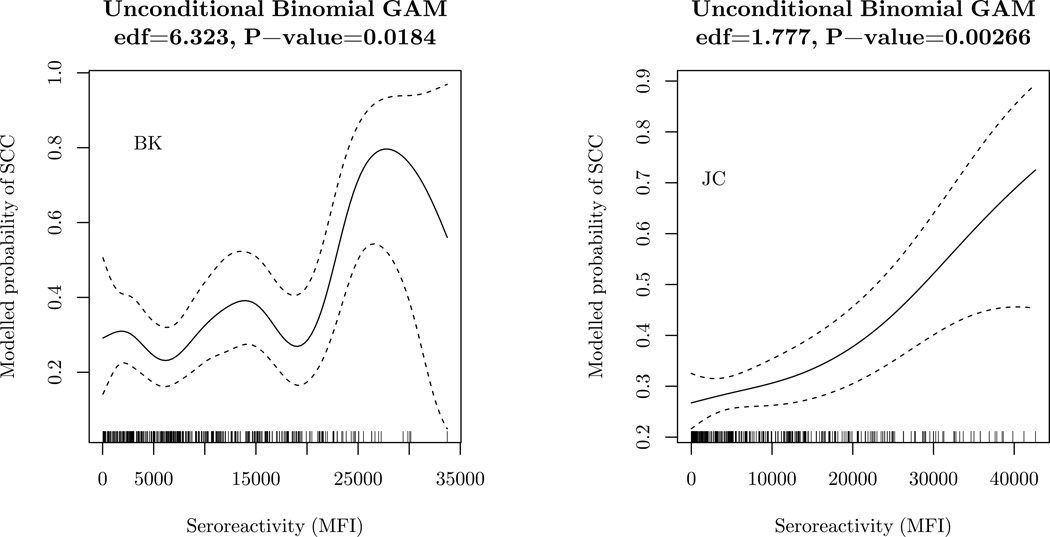

PyV infection was determined using seropositivity for the VP1 protein.

We assessed risk of having a new SCC in relation to prediagnostic PyV seroreactivity among patients with a history of KC (Table 4). In the conditional logistic regression models of the matched cases and controls, an increased risk of SCC was specifically observed with seropositivity for JC (OR= 2.54, 95% CI: 1.23–5.25), and a positive trend in SCC risk was associated with increasing MFI quartiles of JC seroreactivity (P-for-trend=0.004). The highest versus lowest quartile of JC seroreactivity was associated with a 3-fold greater risk of SCC (OR=3.13, 95% CI: 1.51–6.49). In conditional analyses, a positive association with SCC risk was also observed with seropositivity for BK (OR= 3.90, 95% CI: 0.48–31.96) with limited statistical power, and there was evidence of an increasing trend in SCC risk with increasing quartiles of seroreactivity (P-for-trend=0.02). Similar estimates were obtained using unconditional logistic regression models that adjusted for the matching factors: age, gender, and study center (Supplemental Table 2). The binomial GAMs suggested an increasing probability of SCC with increasing continuous MFI values for both BK (P=0.02) and JC (P=0.003) (Figure 2), with some deviations from linearity and statistical imprecision (especially for BK). Analyses stratified by randomization arm, prior SCC status (220 controls and 107 cases with no prior SCC presented with their first incident SCC), prior BCC status (Supplemental Figure 5), smoking status, UV skin damage, and hair color (Supplemental Figure 6) resulted in similar OR estimates as the main analyses but were limited by the markedly reduced sample sizes. The OR associated with JC was higher among those with a skin type that tended to burn, but this was based on small stratum sizes and had wide CIs (Supplemental Figure 6).

Table 4.

Conditional odds ratiosa (95% confidence intervals) for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by seropositivity for each polyomavirus (PyV)b type and quartilesc of PyV seroreactivity at baseline among cases and matched controls(n=306) from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study.

| SCC Cases (n=111) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PyV seroreactivity (MFI units) |

Controls (n=195), No. (%) |

No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| BK | ||||

| Seronegative | 7 (3.6) | 1 (0.9) | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Seropositive | 188 (96.4) | 110 (99.1) | 3.90 (0.48–31.96) | |

| Quartile 1 | 54 (27.7) | 26 (23.4) | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Quartile 2 | 48 (24.6) | 14 (12.6) | 0.65 (0.31–1.37) | |

| Quartile 3 | 46 (23.6) | 32 (28.9) | 1.67 (0.86–3.23) | |

| Quartile 4 | 47 (24.1) | 39 (35.1) | 1.89 (0.96–3.73) | |

| P for trendd | 0.016 | |||

| JC | ||||

| Seronegative | 45 (23.1) | 13 (11.7) | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Seropositive | 150 (76.9) | 98 (88.3) | 2.54 (1.23–5.25) | |

| Quartile 1 | 50 (25.6) | 18 (16.2) | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Quartile 2 | 49 (25.1) | 26 (23.4) | 1.60 (0.76–3.39) | |

| Quartile 3 | 51 (26.1) | 21 (18.9) | 1.10 (0.50–2.44) | |

| Quartile 4 | 45 (23.1) | 46 (41.4) | 3.13 (1.51–6.49) | |

| P for trendd | 0.0039 | |||

OR=odds ratios obtained from conditional logistic regression analysis, CI=confidence interval.

PyV infection was determined in the baseline or earliest serum sample collected using seropositivity for the VP1 protein.

Controls may not be evenly distributed within quartiles due to uneven data distribution and the quartiles based upon all 229 controls.

Based on the seroreactivity quartiles modelled as a continuous variable.

Figure 2.

Modelled probability of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by PyV seroreactivity assessed in the baseline or earliest serum sample collected, with adjustment for continuous age, gender, and study center, in multivariable binomial generalized additive models (binomial GAMs) among 342 study participants from the Skin Cancer Prevention Study. The solid line represents the modelled probability of SCC, and the dashed lines denote the 95% confidence intervals. The rug along the x axis shows the distribution of study participants. The estimated degrees of freedom (edf) and corresponding significance is shown above each plot. The only smoothed (nonparametric) component of the binomial GAM was PyV seroreactivity.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a nested case-control study to test the hypothesis that prediagnostic infection with human PyVs is associated with incident SCC in a population at high risk for this malignancy. Among participants with a history of KC, we found an increased risk of subsequent SCC associated with JC seropositivity, as well as with increasing quartiles of BK and JC seroreactivity, in serum samples collected prior to SCC diagnosis. SCC diagnosis was not associated with a change in BK or JC serostatus, and intraindividual seroreactivity remained consistent over time.

There is limited information on the longitudinal serostability of these viruses within individuals. Available studies on repeated measures of seroreactivity against PyVs have primarily been conducted among special populations such as organ transplant recipients (13, 61), pregnant women (20), and heavily immunosuppressed patients (e.g., HIV-infected individuals (62, 63), or multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab (17–19, 64–66)), with evidence of greater seroinstability over time, possible due to their condition or immunotherapy. A nested case-control study of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma found only 1 change in JC serostatus and 3 changes in BK serostatus over a period of 15 years out of 94 controls (67). One published study aimed to investigate the serostability of PyVs in the general adult population: a longitudinal study of 458 individuals from Australia (12). Over an 11 year follow-up period, BK seroprevalence was stable with only 2.5% displaying a change in serostatus over time (12). However, JC serostatus was less stable during the same span of time, with 16% changing serostatus (12). In our study, we found BK and JC seroreactivity to remain very stable within an individual, as nearly all participants who tested seropositive or seronegative in their first sample retained this status over the course of time. Thus, our findings along with prior work (12, 67) suggest a single measurement of serum antibody level is a reasonable indicator of long-term antibody status for BK and JC in epidemiologic studies of adults.

Research exploring the effect of PyV serostatus prior to diagnosis on future SCC risk is limited, despite evidence of a causal role for MCV in MCC development (24, 68). We found a positive association between JC seropositivity in prediagnostic serum samples and the development of a new primary SCC among those with least one previous KC. Our findings differ from those observed in a large Swedish study, where no association was found between SCC (OR=1.0, 95% CI: 0.8–1.4) and JC seropositivity with samples collected at least 1 month prior to diagnosis (69). However, the Swedish study included JC as a specificity control, as they had the primary objective to investigate the association between HPV and SCC or BCC (69). In a clinic-based case-control study conducted in Florida, USA, a positive but weak association for SCC was observed with JC seropositivity assessed at the time of diagnosis (OR=1.4, 95% CI: 0.9–2.2) (39). Our findings support this result, and further suggest a lack of bias from analysis of post-diagnosis samples. We also explored the risk of SCC in relation to the presence of prediagnostic antibodies against BK, but the high seroprevalence resulted in elevated but less stable estimates of SCC risk.

Infection with BK and JC has been categorized as ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans’ by the International Agency for Research in Cancer (70), although the mechanism is not well understood. The early PyV protein, LTAg contains a retinoblastoma (Rb)-binding pocket necessary for transforming activity and cell proliferation (2, 4, 24, 71), and also harbors a p53-binding domain that binds and inactivates the p53 protein to induce cell division (2, 5, 71, 72). JC LTAg has been shown to directly interact with insulin receptor substrate-1 (73) and β-catenin (74, 75), resulting in a nuclear translocation of proteins that may contribute to the process of malignant transformation through the dysregulation of homologous recombination-directed DNA repair (76) and the proto-oncogene c-myc (75). BK and JC differ from other PyV types, as their late regions encode an agnoprotein which may exert its tumorigenic influence through cell cycle dysregulation, interference with DNA repair processes, and chromosome instability (77, 78). Moreover, BK, JC, and MCV also encode a miRNA that downregulates LTAg expression, which may allow the virus to escape immune surveillance (79).

A history of PyV infection assessed through antibody detection against a viral antigen implies that either viral action or confounding by an immune trait (80) related to both infection and SCC risk may be responsible for skin carcinogenesis. BK and JC are known to reactivate under conditions of immunosuppression (e.g., organ transplantation) due to impaired cellular immune responses and decreased immune surveillance (22, 81, 82). Further, we previously found specific PyVs to be associated with slight changes in adaptive lymphocyte proportions among immunocompetent individuals using a bioinformatics approach (83). As adaptive immunity is modulated by both genetics and exposure to infections or allergens, and plays a role in future cancer risk, research causally linking viruses and SCC is complicated by their shared association with immune dysfunction (80).

Strengths and limitations

We leveraged a unique trial with follow-up and serial serum samples to prospectively assess the relationship between SCC and PyV seroreactivity in a nested case-control study. Our prospective design reduced the possibility of reverse-causality with respect to the new occurrence of SCC – a concern of particular relevance for skin cancers, where the seroprevalence of HPV infections has been suspected to increase following diagnosis (84). Our data suggest that PyV reactivation or increased susceptibility caused by the disease process are less likely to explain the observed associations. Nonetheless, the use of a high risk study sample comprised of patients with a history of KCs in an intervention trial may limit the generalizability of our results. As all study participants had a history of KC, our study design does not exclude the possibility that the initial KC diagnosis prior to trial enrollment affected seroreactivity measurements.

Antibody response against each PyV type was used as a marker of PyV infection (49, 85), measured using multiplex serology and a GST fusion protein-based capture immunoassay of recombinantly expressed VP1 capsid proteins, This has been shown a reliable technique to assess PyV seroreactivity and used as a marker of PyV infection in prior studies (39, 44, 49, 85). We found antibody levels against BK and JC to be strongly correlated within individuals over time, and did not find evidence of cross-reactivity between BK and JC VP1 antibodies, suggesting our results to be virus-specific. A limitation of our study is the lack of measures for BK or JC virus in SCC tumors. Serum MFI values have been shown to correspond to the presence of viral DNA within tumor tissues, with MCV DNA-positive SCC tumors (but not MCV DNA-negative SCC tumors) having notably higher MFI values compared to controls (39); yet far less is known about the other PyV types. While other studies have failed to detect DNA from either virus types in Bowen’s disease (86), BCC (87), SCC (39, 87, 88), or melanoma (88, 89), BK DNA has been amplified from 76% of healthy skin tissues, and JC DNA from 16% of normal skin (90). This suggests that these viruses can inhabit the skin even without being skin tropic (2). In addition, BK (but not JC) early promoters displayed strong activity in experimental skin cell lines, which may indicate skin is suitable for polyomaviral propagation (91). Another limitation is that a history of PyV infection inferred from antibody detection suggests either the virus itself or a confounding immunologic factor may be responsible for SCC development. Thus, our findings of an association between BK or JC and SCC could represent the predisposing role of an immune phenotype, rather than the carcinogenic action of the virus.

Conclusions

We found evidence for an association between prediagnostic seroreactivity to BK and JC, and subsequent risk of SCC development in a USA adult population at high risk for KC. Further, our data suggest that seroreactivity to BK and JC is relatively stable over a period of up to 6 years, and following an SCC diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by grant R01CA057494 awarded to Dr. Margaret R. Karagas from the NIH/NCI, grant P20GM104416 from COBRE, and grant K01LM011985 awarded to Dr. Anne G. Hoen.

The authors would like to thank the study investigators, staff, and participants of the Skin Cancer Prevention Study, as well as physicians and the pathology labs involved in the study group, without whom this work would not be possible.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- GAM

generalized additive model

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- ICC

intraclass correlation coefficient

- IQR

interquartile range

- JC

John Cunningham virus

- KC

keratinocyte cancer

- MCV

Merkel cell polyomavirus

- MFI

median fluorescence intensity

- OR

odds ratio

- PyV

polyomavirus

- SCC

cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

- TAg

T antigen

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Randhawa P, Vats A, Shapiro R. The pathobiology of polyomavirus infection in man. Polyomaviruses and Human Diseases: Springer. 2006:148–159. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32957-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases. Pathology research international. 2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/123491. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalili K, Stoner GL. Human polyomaviruses: molecular and clinical perspectives. Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Luca A, Baldi A, Esposito V, Howard CM, Bagella L, Rizzo P, et al. The retinoblastoma gene family pRb/p105, p107, pRb2/p130 and simian virus-40 large T-antigen in human mesotheliomas. Nature Medicine. 1997;3:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbone M, Rizzo P, Grimley PM, Procopio A, Mew DJ, Shridhar V, et al. Simian virus-40 large-T antigen binds p53 in human mesotheliomas. Nature Medicine. 1997;3:908–912. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trusch F, Klein M, Finsterbusch T, Kühn J, Hofmann J, Ehlers B. Seroprevalence of human polyomavirus 9 and cross-reactivity to African green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirus. Journal of General Virology. 2012;93:698–705. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.039156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicol JT, Robinot R, Carpentier A, Carandina G, Mazzoni E, Tognon M, et al. Age-specific seroprevalences of merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomaviruses 6, 7, and 9, and trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2013;20:363–368. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00438-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicol JT, Touzé A, Robinot R, Arnold F, Mazzoni E, Tognon M, et al. Seroprevalence and cross-reactivity of human polyomavirus 9. Emerging infectious diseases. 2012;18:1329. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Mattila PS, Jartti T, Ruuskanen O, Söderlund-Venermo M, Hedman K. Seroepidemiology of the newly found trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204:1523–1526. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neske F, Prifert C, Scheiner B, Ewald M, Schubert J, Opitz A, et al. High prevalence of antibodies against polyomavirus WU, polyomavirus KI, and human bocavirus in German blood donors. BMC infectious diseases. 2010;10:215. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Šroller V, Hamšíková E, Ludvíková V, Vochozková P, Kojzarová M, Fraiberk M, et al. Seroprevalence rates of BKV, JCV, and MCPyV polyomaviruses in the general Czech Republic population. Journal of medical virology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jmv.23841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonsson A, Green AC, Mallitt KA, O'Rourke PK, Pawlita M, Waterboer T, et al. Prevalence and stability of antibodies to the BK and JC polyomaviruses: a long-term longitudinal study of Australians. The Journal of general virology. 2010;91:1849–1853. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonsson A, Pawlita M, Feltkamp MC, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S, Harwood CA, et al. Longitudinal study of seroprevalence and serostability of the human polyomaviruses JCV and BKV in organ transplant recipients. Journal of medical virology. 2013;85:327–335. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bressollette-Bodin C, Coste-Burel M, Hourmant M, Sebille V, Andre-Garnier E, Imbert-Marcille BM. A prospective longitudinal study of BK virus infection in 104 renal transplant recipients. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2005;5:1926–1933. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doucette KE, Pang XL, Jackson K, Burton I, Carbonneau M, Cockfield S, et al. Prospective monitoring of BK polyomavirus infection early posttransplantation in nonrenal solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2008;85:1733–1736. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181722ead. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Razonable RR, Brown RA, Humar A, Covington E, Alecock E, Paya CV. A longitudinal molecular surveillance study of human polyomavirus viremia in heart, kidney, liver, and pancreas transplant patients. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2005;192:1349–1354. doi: 10.1086/466532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jilek S, Jaquiery E, Hirsch HH, Lysandropoulos A, Canales M, Guignard L, et al. Immune responses to JC virus in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:264–272. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trampe AK, Hemmelmann C, Stroet A, Haghikia A, Hellwig K, Wiendl H, et al. Anti-JC virus antibodies in a large German natalizumab-treated multiple sclerosis cohort. Neurology. 2012;78:1736–1742. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182583022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryschkewitsch CF, Jensen PN, Monaco MC, Major EO. JC virus persistence following progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:384–391. doi: 10.1002/ana.22137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stolt A, Sasnauskas K, Koskela P, Lehtinen M, Dillner J. Seroepidemiology of the human polyomaviruses. Journal of General Virology. 2003;84:1499–1504. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2013;11:264–276. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang M, Abend JR, Johnson SF, Imperiale MJ. The role of polyomaviruses in human disease. Virology. 2009;384:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imperiale MJ. The human polyomaviruses, BKV and JCV: molecular pathogenesis of acute disease and potential role in cancer. Virology. 2000;267:1–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shuda M, Feng H, Kwun HJ, Rosen ST, Gjoerup O, Moore PS, et al. T antigen mutations are a human tumor-specific signature for Merkel cell polyomavirus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:16272–16277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806526105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reisinger DM, Shiffer JD, Cognetta AB, Jr, Chang Y, Moore PS. Lack of evidence for basal or squamous cell carcinoma infection with Merkel cell polyomavirus in immunocompetent patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:400–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter JJ, Paulson KG, Wipf GC, Miranda D, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus–specific antibodies with Merkel cell carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101:1510–1522. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwa RE, Campana K, Moy RL. Biology of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992;26:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70001-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;68:957–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glass AG, Hoover RN. The emerging epidemic of melanoma and squamous cell skin cancer. Jama. 1989;262:2097–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karagas MR, Greenberg ER, Spencer SK, Stukel TA, Mott LA. Increase in incidence rates of basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer in New Hampshire, USA. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;81:555–559. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990517)81:4<555::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the US Population, 2012. JAMA dermatology. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, Hinckley MR, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Archives of dermatology. 2010;146:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brash DE, Rudolph JA, Simon JA, Lin A, McKenna GJ, Baden HP, et al. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1991;88:10124–10128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.English DR, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, Winter MG, Heenan PJ, Randell PL. Case-control study of sun exposure and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. International journal of cancer. 1998;77:347–353. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980729)77:3<347::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birkeland SA, Storm HH, Lamm LU, Barlow L, Blohmé I, Forsberg B, et al. Cancer risk after renal transplantation in the Nordic countries, 1964–1986. International journal of cancer. 1995;60:183–189. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adami J, Gäbel H, Lindelöf B, Ekström K, Rydh B, Glimelius B, et al. Cancer risk following organ transplantation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. British journal of cancer. 2003;89:1221–1227. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinlen L, Sheil A, Peto J, Doll R. Collaborative United Kingdom-Australasian study of cancer in patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs. British medical journal. 1979;2:1461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6203.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rollison DE, Giuliano AR, Messina JL, Fenske NA, Cherpelis BS, Sondak VK, et al. Case–control study of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:74–81. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madeleine MM, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, Wipf GC, Davis C, Berg D, et al. Risk of squamous cell skin cancer after organ transplant associated with antibodies to cutaneous papillomaviruses, polyomaviruses, and TMC6/8 (EVER1/2) variants. Cancer medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cam4.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenberg ER, Baron JA, Stevens MM, Stukel TA, Mandel JS, Spencer SK, et al. The Skin Cancer Prevention Study: design of a clinical trial of beta-carotene among persons at high risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Controlled clinical trials. 1989;10:153–166. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg ER, Baron JA, Stukel TA, Stevens MM, Mandel JS, Spencer SK, et al. A clinical trial of beta carotene to prevent basal-cell and squamous-cell cancers of the skin. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323:789–795. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009203231204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karagas MR, Greenberg ER, Nierenberg D, Stukel TA, Morris JS, Stevens MM, et al. Risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in relation to plasma selenium, alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene, and retinol: a nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 1997;6:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kjærheim K, Røe OD, Waterboer T, Sehr P, Rizk R, Dai HY, et al. Absence of SV40 antibodies or DNA fragments in prediagnostic mesothelioma serum samples. International journal of cancer. 2007;120:2459–2465. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gardner S, Field A, Coleman D, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (BK) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. The Lancet. 1971;297:1253–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padgett B, Zurhein G, Walker D, Eckroade R, Dessel B. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. The Lancet. 1971;297:1257–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sehr P, Müller M, Höpfl R, Widschwendter A, Pawlita M. HPV antibody detection by ELISA with capsid protein L1 fused to glutathione S-transferase. Journal of virological methods. 2002;106:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waterboer T, Sehr P, Michael KM, Franceschi S, Nieland JD, Joos TO, et al. Multiplex human papillomavirus serology based on in situ–purified glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. Clinical chemistry. 2005;51:1845–1853. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antonsson A, Green AC, Mallitt K-A, O'Rourke PK, Pawlita M, Waterboer T, et al. Prevalence and stability of antibodies to the BK and JC polyomaviruses: a long-term longitudinal study of Australians. Journal of General Virology. 2010;91:1849–1853. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michael KM, Waterboer T, Sehr P, Rother A, Reidel U, Boeing H, et al. Seroprevalence of 34 human papillomavirus types in the German general population. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4:e1000091. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pastrana DV, Wieland U, Silling S, Buck CB, Pfister H. Positive correlation between Merkel cell polyomavirus viral load and capsid-specific antibody titer. Medical microbiology and immunology. 2012;201:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s00430-011-0200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waterboer T, Neale R, Michael KM, Sehr P, de Koning MN, Weißenborn SJ, et al. Antibody responses to 26 skin human papillomavirus types in the Netherlands, Italy and Australia. Journal of General Virology. 2009;90:1986–1998. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.010637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karagas MR, Nelson HH, Sehr P, Waterboer T, Stukel TA, Andrew A, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and incidence of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas of the skin. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:389–395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fleiss J. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. Taylor & Francis; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Antonsson A, Green AC, Mallitt K-a, O'Rourke PK, Pandeya N, Pawlita M, et al. Prevalence and stability of antibodies to 37 human papillomavirus types—a population-based longitudinal study. Virology. 2010;407:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleiss JL, Levin BR, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Vol. 203. Hoboken, NJ: J Wiley-Interscience; 2003. p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and psychological measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothman K. Epidemiology An Introduction. London: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wood SN. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2011;73:3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wood S. Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. CRC press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Randhawa P, Bohl D, Brennan D, Ruppert K, Ramaswami B, Storch G, et al. Longitudinal analysis of levels of immunoglobulins against BK virus capsid proteins in kidney transplant recipients. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2008;15:1564–1571. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00206-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iannetta M, Bellizzi A, Lo Menzo S, Anzivino E, D'Abramo A, Oliva A, et al. HIV-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: longitudinal study of JC virus non-coding control region rearrangements and host immunity. J Neurovirol. 2013;19:274–279. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Flo RW, Nilsen A, Voltersvik P, Haukenes G. Serum antibodies to viral pathogens and Toxoplasma gondii in HIV-infected individuals. Apmis. 1993;101:946–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1993.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, Richman S, Pace A, Lee S, et al. Anti-JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:802–812. doi: 10.1002/ana.24286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dominguez-Mozo MI, Garcia-Montojo M, De Las Heras V, Garcia-Martinez A, Arias-Leal AM, Casanova I, et al. Anti-JCV antibodies detection and JCV DNA levels in PBMC, serum and urine in a cohort of Spanish Multiple Sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology. 2013;8:1277–1286. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9496-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin J, Bettin P, Lee JK, Ho JK, Sadiq SA. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum JC virus antibody detection in multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2013;261:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rollison DE, Engels EA, Halsey NA, Shah KV, Viscidi RP, Helzlsouer KJ. Prediagnostic circulating antibodies to JC and BK human polyomaviruses and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:543–550. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Foulongne V, Kluger N, Dereure O, Brieu N, Guillot B, Segondy M. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma, France. Emerging infectious diseases. 2008;14:1491. doi: 10.3201/eid1409.080651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andersson K, Michael KM, Luostarinen T, Waterboer T, Gislefoss R, Hakulinen T, et al. Prospective study of human papillomavirus seropositivity and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer. American journal of epidemiology. 2012:kwr373. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bouvard V, Baan RA, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, et al. Carcinogenicity of malaria and of some polyomaviruses. The lancet oncology. 2012;13:339–340. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Topalis D, Andrei G, Snoeck R. The large tumor antigen: A “Swiss Army knife” protein possessing the functions required for the polyomavirus life cycle. Antiviral research. 2013;97:122–136. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pipas JM. SV40: Cell transformation and tumorigenesis. Virology. 2009;384:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lassak A, Del Valle L, Peruzzi F, Wang JY, Enam S, Croul S, et al. Insulin receptor substrate 1 translocation to the nucleus by the human JC virus T-antigen. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:17231–17238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Enam S, Del Valle L, Lara C, Gan D-D, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Palazzo JP, et al. Association of Human Polyomavirus JCV with Colon Cancer Evidence for Interaction of Viral T-Antigen and β-Catenin. Cancer research. 2002;62:7093–7101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gan D-D, Reiss K, Carrill T, Del Valle L, Croul S, Giordano A, et al. Involvement of Wnt signaling pathway in murine medulloblastoma induced by human neurotropic JC virus. Oncogene. 2001;20:4864–4870. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trojanek J, Ho T, Del Valle L, Nowicki M, Wang JY, Lassak A, et al. Role of the insulin-like growth factor I/insulin receptor substrate 1 axis in Rad51 trafficking and DNA repair by homologous recombination. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:7510–7524. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7510-7524.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Darbinyan A, Darbinian N, Safak M, Radhakrishnan S, Giordano A, Khalili K. Evidence for dysregulation of cell cycle by human polyomavirus JCV, late auxiliary protein. Oncogene. 2002;21:5574–5581. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Darbinyan A, White MK, Akan S, Radhakrishnan S, Del Valle L, Amini S, et al. Alterations of DNA damage repair pathways resulting from JCV infection. Virology. 2007;364:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moens U. Silencing viral microRNA as a novel antiviral therapy? BioMed Research International. 2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/419539. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Michaud DS, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. Understanding the role of the immune system in the development of cancer: new opportunities for population-based research. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2015;24:1811–1819. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saundh BK, Tibble S, Baker R, Sasnauskas K, Harris M, Hale A. Different patterns of BK and JC polyomavirus reactivation following renal transplantation. Journal of clinical pathology. 2010;63:714–718. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.074864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wiedinger K, Bitsaktsis C, Chang S. Reactivation of human polyomaviruses in immunocompromised states. Journal of NeuroVirology. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0234-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gossai A, Waterboer T, Nelson HH, Michel A, Willhauck-Fleckenstein M, Farzan SF, et al. Seroepidemiology of Human Polyomaviruses in a US Population. Am J Epidemiol. 2015 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Casabonne D, Michael KM, Waterboer T, Pawlita M, Forslund O, Burk RD, et al. A prospective pilot study of antibodies against human papillomaviruses and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma nested in the Oxford component of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;121:1862–1868. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Waterboer T, Sehr P, Pawlita M. Suppression of non-specific binding in serological Luminex assays. Journal of immunological methods. 2006;309:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mertz KD, Pfaltz M, Junt T, Schmid M, Figueras MTF, Pfaltz K, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in common warts and carcinoma in situ of the skin. Human pathology. 2010;41:1369–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ganzenmueller T, Yakushko Y, Kluba J, Henke-Gendo C, Gutzmer R, Schulz TF. Next-generation sequencing fails to identify human virus sequences in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2012;131:E1173–E1179. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wold WS, Mackey JK, Brackmann KH, Takemori N, Rigden P, Green M. Analysis of human tumors and human malignant cell lines for BK virus-specific DNA sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1978;75:454–458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Giraud G, Ramqvist T, Ragnarsson-Olding B, Dalianis T. DNA from BK virus and JC virus and from KI, WU, and MC polyomaviruses as well as from simian virus 40 is not detected in non-UV-light-associated primary malignant melanomas of mucous membranes. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3595–3598. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01635-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Monini P, Rotola A, de Lellis L, Corallini A, Secchiero P, Albini A, et al. Latent BK virus infection and Kaposi's sarcoma pathogenesis. International journal of Câncer. 1996;66:717–722. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960611)66:6<717::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moens U, Van Ghelue M, Ludvigsen M, Korup-Schulz S, Ehlers B. The early and late promoters of BKPyV, MCPyV, TSPyV, and HPyV12 are among the strongest of all known human polyomaviruses in 10 different cell lines. The Journal of general virology. 2015 doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.