Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To investigate the relationship between vestibular loss associated with aging and age-related decline in visuospatial function.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional analysis within a prospective cohort study.

SETTING

Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA).

PARTICIPANTS

Community-dwelling BLSA participants with a mean age of 72 (range 26–91) (N = 183).

MEASUREMENTS

Vestibular function was measured using vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials. Visuospatial cognitive tests included Card Rotations, Purdue Pegboard, Benton Visual Retention Test, and Trail-Making Test Parts A and B. Tests of executive function, memory, and attention were also considered.

RESULTS

Participants underwent vestibular and cognitive function testing. In multiple linear regression analyses, poorer vestibular function was associated with poorer performance on Card Rotations (P = .001), Purdue Pegboard (P = .005), Benton Visual Retention Test (P = 0.008), and Trail-Making Test Part B (P = .04). Performance on tests of executive function and verbal memory were not significantly associated with vestibular function. Exploratory factor analyses in a subgroup of participants who underwent all cognitive tests identified three latent cognitive abilities: visuospatial ability, verbal memory, and working memory and attention. Vestibular loss was significantly associated with lower visuospatial and working memory and attention factor scores.

CONCLUSION

Significant consistent associations between vestibular function and tests of visuospatial ability were observed in a sample of community-dwelling adults. Impairment in visuospatial skills is often one of the first signs of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Further longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate whether the relationship between vestibular function and visuospatial ability is causal.

Keywords: vestibular function, cognition, aging, visuospatial ability

Numerous lines of evidence— epidemiological, physiological, histopathological— have shown that vestibular function declines with age.1–4 The vestibular system is known for its role in maintaining balance and postural control, and several studies have noted associations between vestibular loss and balance impairment and falls in older individuals.5–7 Increasing evidence demonstrates important connections between the vestibular system and various domains of cognitive function, most notably visuospatial ability, but also memory, executive function, and attention.8–11 Studies in animals and individuals with unilateral or bilateral vestibular loss suggest that the vestibular system provides critical information about spatial orientation, spatial memory, and spatial navigation.10–13

Visuospatial ability deteriorates with age. Studies have shown that older individuals have greater difficulty with navigation in real-world and virtual environments. Older adults make more errors in returning to their starting locations and have greater difficulty remembering locations of previously observed targets.14–17 In addition, perception of subjective visual vertical also appears to degrade with age, with greater deviations from true vertical observed in healthy older than younger adults.18 It is unknown whether vestibular loss associated with age plays a role in the degradation of these critical spatial cognitive functions in elderly adults. This link may be important to establish, given that declines in spatial orientation and navigation may mediate the association between age-related vestibular loss and falls.

The current study used data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) to evaluate the cross-sectional association between vestibular function and selected domains of cognitive function, including visuospatial ability, memory, executive function, and attention. The function of the saccule, the vestibular end organ responsible for measuring changes in spatial orientation with respect to gravity, was specifically considered. Based on the existing literature, it was hypothesized that vestibular function would have the strongest association with visuospatial ability. A series of structural equation models was developed to evaluate the extent to which vestibular function may mediate age-related changes in cognition. These analyses offer insight into the mechanisms by which peripheral vestibular sensitivity may be associated with specific cognitive functions and may inform future research on preventive and treatment strategies for age-related cognitive decline.

METHODS

Study Participants

The BLSA is a prospective cohort study of participant volunteers aged 21 to 103 in the National Institute on Aging Clinical Research Unit at Harbor Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. This study evaluated a cross-sectional sample of BLSA participants who underwent vestibular testing and cognitive function testing starting in February 2013, when a vestibular testing battery was added to the BLSA. All participants provided written informed consent, and the hospital institutional review board approved the BLSA study protocol. All BLSA participants with valid vestibular and cognitive testing data were evaluated, and individuals were not excluded based on a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. One participant had mild cognitive impairment and one had Alzheimer’s disease. Excluding these individuals from the analysis did not substantively change the findings, so the findings with these participants included are presented.

Vestibular Function Tests

Vestibular physiological tests were added to the BLSA test battery in February 2013, including the cervical vestibular-evoked myogenic potential test (cVEMP) in response to sound. cVEMP testing methods of measuring saccular function have been published in detail previously and are discussed briefly here.19,20 Participants sat on a chair inclined at 30° from the horizontal. Trained examiners placed recording electromyographic (EMG) electrodes on the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles and at the sternoclavicular junction bilaterally, and a ground electrode was placed on the manubrium sterni. Sound stimuli consisted of 500 Hz, 125 dB sound pressure level tone bursts delivered monaurally through headphones. Amplitudes of cVEMP response were recorded and normalized for the background EMG activity recorded in the 10 ms before stimulus onset. The cVEMP amplitude of the better ear was used for the analysis. Participants with absent responses were excluded from analyses, based on previously established analytical standards.2,20 Of the 247 BLSA participants tested, 183 had evaluable cVEMP responses (64 excluded for absent cVEMPs bilaterally) and were included in analyses. Participants without cVEMP responses were significantly older (78.8) than participants with responses (70.6) (P < .001).

Cognitive Tests

Trained, certified examiners performed neurocognitive testing in the BLSA. Testing examined a number of cognitive domains, including general mental status (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)), visuospatial ability (Card Rotations Test, Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT), Trail-Making Test (TMT) Parts A and B, Purdue Pegboard Test), verbal memory (California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), Digit Span), executive function (Backward Digit Span, Trail-Making Test Part B, Category and Letter fluency), attention (TMT A, Forward Digit Span, Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST)). Each test will be briefly described here.

Mini–Mental State Examination

The MMSE is a brief test of mental status used in clinical practice to screen for cognitive impairment and dementia.21 It has a maximum score of 30 points. In the BLSA, only participants aged 60 and older were administered the MMSE. Sixty-three participants had missing responses.

Card Rotations Test

The card rotations test is used to assess visuospatial ability, specifically spatial rotational ability. Subjects are shown a reference shape, followed by a series of similar objects that are variously rotated. Subjects are asked to mentally rotate the objects to determine whether they are identical to or mirror images of the reference shape.22 The score is the number classified correctly minus the number classified incorrectly. Ten participants had missing responses.

Purdue Pegboard Test

The Purdue Pegboard Test measures visuomotor integration and manual dexterity. Subjects place pegs from a cup in small holes on a board, and the number of pegs they are able to place in 30 seconds is recorded over two trials and averaged.23 It is performed separately with the dominant and nondominant hand; results of both and the mean are reported. Twenty-eight had missing responses for the nondominant hand, and 31 had missing responses for the dominant hand.

Benton Visual Retention Test

The BVRT is used to assess nonverbal memory and visuoconstructional skill. Participants are shown 10 cards, each containing geometric shapes for 10 seconds each, and are then asked to draw the shapes on a blank piece of paper when the original image is removed. The total number of errors across the 10 cards was the outcome measure in our analysis.24 Seventeen participants had missing responses.

TMT A and B

The TMT is used to assess attention, visuospatial scanning, executive function, and processing speed. In the TMT A, participants are asked to connect a series of numbers in consecutive order (1, 2, 3, etc.). The TMT A examines attention, processing speed, and visual scanning ability. In the TMT B, participants are asked to connect a series of letters and numbers in alternating consecutive order (1, A, 2, B, 3, C, etc.). The TMT B examines executive function, set-shifting, attention, processing speed, and visual scanning ability. The time in seconds to complete the task is recorded.25 Forty-nine participants had missing responses on TMT A, and 53 had missing responses on TMT B.

Forward and Backward Digit Span Test

The digit span portion of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale— Revised is used to assess short-term verbal memory and mental manipulation.26 Participants are asked to recall increasingly longer lists of digits until they are no longer able to report back accurately. Forward recall assesses attention and short-term memory, and backward recall (whereby participants report the digits in reverse order) assesses short-term memory and mental manipulation. The maximum number of digits recalled is recorded. Nineteen participants had missing responses on Backward Digit Span and 21 on Forward Digit Span.

California Verbal Learning Test

The CVLT assesses verbal learning and memory.27 Participants are read a shopping list of 16 items five times and asked to recall the items immediately after each repetition and then after a 20-minute delay. The current analysis considered the sum of the five immediate recall trials (immediate total) and the delayed recall trial. Forty-three participants had missing responses on immediate total recall and 45 on delayed recall.

Category and Letter Fluency Tests

The Category Fluency Test assesses executive function. Participants are asked to name animals, fruits, and vegetables for 1 minute each. Similarly, the Letter Fluency test asks participants to list as many words as they can beginning with the letters F, A, and S for 1 minute each.28 The outcome for Category and Letter Fluency is the mean number of words listed. Forty-nine participants had missing responses for the Category and Letter Fluency Tests.

Digit Symbol Substitution Test

The DSST is used to assess attention, visuospatial ability, and set shifting. It consists of a series of nine digit–symbol pairs and a string of digits. Participants are asked to record the symbol that corresponds to each of the digits. The final score is the number of correct digit–symbol substitutions completed in 90 seconds.29 Twenty-five participants had missing responses on the DSST.

Hearing and Vision Testing

Trained examiners performed audiometry in a soundproof booth using headphones. Pure tone averages (PTAs) were calculated based on the mean of the audiometric thresholds at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz in the betterhearing ear. Thirty participants were excluded from testing because of impacted cerumen. Trained examiners tested visual acuity using an autorefractor and analyzed it in log-MAR units. Eight participants had missing vision data.

Other Covariates

Demographic, cardiovascular risk factor data, and smoking history were collected from extensive participant interviews. Participants were grouped into three race categories: white, black, or other. Number of years of education was recorded. History of hypertension was ascertained by asking participants, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever said you had high blood pressure or hypertension?” Three participants had missing hypertension data. History of diabetes mellitus was ascertained by asking participants, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever said you had diabetes, glucose intolerance, or high blood sugar?” Four participants had missing diabetes mellitus data. History of smoking was ascertained by asking participants “Have you smoked at least one hundred cigarettes over your entire life?” “Have you smoked at least fifty cigars over your entire life?” and “Have you smoked at least three packages of pipe tobacco over your entire life?” An affirmative answer to any of these questions constituted a positive smoking history. Six participants had missing smoking data.

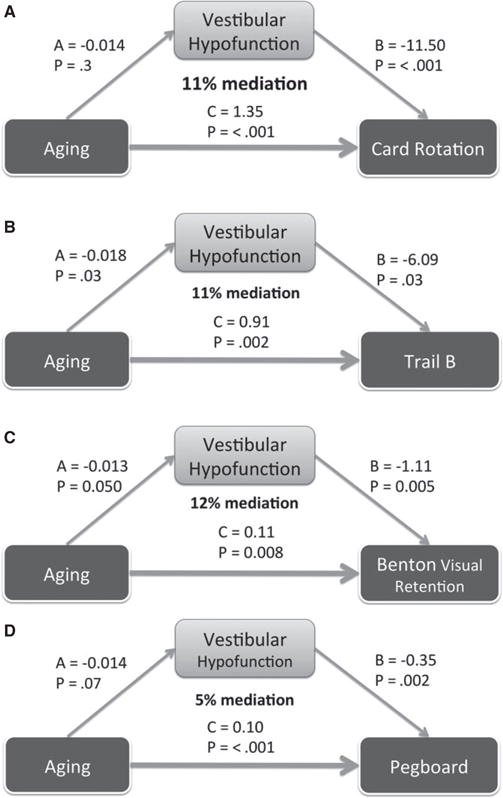

Statistical Analysis

A sample size calculation was performed to estimate the number of participants needed to estimate the association between saccular and cognitive function in regression analyses, using an alpha level of .05 and a power of 0.80. Pilot cVEMP data from a normative sample of older adults was used for the calculations, and visuospatial cognitive tests for which there were previously published BLSA sample data (Card Rotations and BVRT) were considered as primary outcomes.14,30 The estimated sample sizes for the five tests ranged from 95 to 153. Multiple linear regression was used to estimate the association between vestibular and cognitive function in two models. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, and education, and Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vision, and hearing. A series of structural equation models was developed to test hypotheses about whether vestibular function mediates the association between age and cognitive performance. The fraction of this association that variation in vestibular function mediated was calculated from these structural equation models (Figure 1). Exploratory factor analysis was also performed to identify latent cognitive abilities underlying the multiple cognitive tests. The parallel test was used to determine the number of factors to retain. The factors identified in this analysis were then used in multiple linear regression Models 1 and 2. Coefficients were considered statistically significant at P < .05. Stata version 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) was used for all analyses.

Figure 1.

Structural equation models of vestibular function as a partial mediator of the association between age and visuospatial cognitive tests. All models were adjusted for demographic, cardiovascular, and sensory risk factors, as in the Model 2 regressions. Percentage mediation is calculated based on the formula: (A*B)/(A*B)+C, where A*B is the indirect effect of age on cognitive function mediated by vestibular function, C is the direct effect of age on cognitive function, and (A*B)+C is the total effect of age on cognitive function. (A) Structural equation model of association between age, vestibular function and the Card Rotation test (n = 136). Vestibular function mediates 11% of the association between age and Card Rotation test score. (B) Structural equation model of association between age, vestibular function, and the Trail-Making Test (TMT) Part B (n = 104). Vestibular function mediates 11% of the association between age and TMT B time. (C) Structural equation model of association between age, vestibular function, and the Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT) (n = 133). Vestibular function mediated 12% of the association between age and BVRT performance. (D) Structural equation model of association between age, vestibular function, and the Purdue Pegboard test (n = 117). Vestibular function mediates 5% of the association between age and Purdue Pegboard test score.

RESULTS

One hundred eighty-three participants with a mean age of 70.2 ± 13.0 (range 26–91) were included in the analyses (Table 1); 46% were male; 68% were white, 25% were black, and 7% were other. The majority of participants had more than a college education. With respect to cardiovascular risk factors, 38% of participants reported a positive smoking history, 47% reported hypertension, and 17% reported diabetes mellitus (Table 1). Mean logMAR visual acuity with corrective lenses was 0.05 ±.13, corresponding to a visual acuity between 20/20 and 20/25. The mean PTA hearing threshold was 27 ± 14 dB. The mean performance of the study sample on each of the cognitive tests was also evaluated (Table 2). One participant had a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and another of dementia. Excluding these two participants did not affect the results, so both were included in the analyses reported below.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2013 (N = 183)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 70.2 ± 13 |

| Cervical vestibular-vestibular-evoked myogenic potential test amplitude, μV, mean ± SD | 1.50 ± 0.96 |

| Sex, % | |

| Male | 46 |

| Female | 54 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 68 |

| Black | 25 |

| Other | 7 |

| Education, years, mean ± SD | 17.3 ± 2.7 |

| Smoking, % | |

| Never smoker | 62 |

| ≥100 lifetime cigarettes | 38 |

| Hypertension, % | |

| No | 53 |

| Yes | 47 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | |

| No | 83 |

| Yes | 17 |

| Vision, logMAR, mean ± SD | 0.05 ± 0.13 |

| Hearing, dB threshold, mean ± SD | 27 ± 14 |

SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Cognitive Testing in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (N = 183)

| Cognitive Test | N | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Mental status: Mini–Mental State Examination | 120 | 28.7 ± 1.4 |

| Visuospatial ability | ||

| Card rotations | 173 | 84.5 ± 39.5 |

| Purdue pegboard | ||

| Dominant | 152 | 12.5 ± 2.1 |

| Nondominant | 155 | 12.0 ± 2.0 |

| Mean | 150 | 12.2 ± 1.9 |

| Benton visual retention test, errors | 168 | 8.1 ± 4.8 |

| Trail-making test part A, seconds | 134 | 31.8 ± 14.4 |

| Trail-making test part B, seconds | 130 | 76.4 ± 35.7 |

| Memory: California verbal learning test | ||

| Immediate recall total | 140 | 53.0 ± 12.5 |

| Delayed recall | 138 | 11.3 ± 3.4 |

| Executive function | ||

| Backward digit span | 164 | 5.1 ± 1.4 |

| Category fluency, mean | 134 | 16.6 ± 3.6 |

| Letter fluency, mean | 134 | 15.0 ± 4.3 |

| Attention | ||

| Forward digit span | 162 | 6.5 ± 1.3 |

| Digit symbol substitution test | 158 | 43.4 ± 12.6 |

The association between vestibular function and specific domains of cognitive function was evaluated using two multivariate linear regression models. Model 1 included age, sex, race, and education, and Model 2 added cardiovascular risk factors, vision, and hearing. To facilitate interpretation, the model coefficients were transformed such that a negative coefficient always indicated that poorer vestibular function was associated with poorer cognitive function. Significant associations were found between vestibular function and performance on Card Rotations, Purdue Pegboard, BVRT, and TMT B in Models 1 and 2 (Table 3). Vestibular function was significantly associated with MMSE score in Model 2 but not Model 1. Specifically, in Model 2, each 1-μV lower rectified cVEMP amplitude was associated with a 11.5 lower Card Rotations score (P = .001), a 0.35-peg lower Purdue Pegboard score (P = .005), 1.11 more errors on the BVRT (P = .008), a 6.09-second slower TMT B time (P = .04), and a 0.32-point lower MMSE score (P = .03). Vestibular function was not significantly associated with memory tests, specifically poorer vestibular function was not associated with fewer recalled items on the immediate total (P = .07) and delayed recall (P = .05) portions of the CVLT. Tests of executive function (Backward Digit Span, Category and Letter Fluency), tests of attention (Forward Digit Span, DSST), and TMT A were not significantly associated with vestibular function (Table 3). See Online Appendix S1 for coefficients and P-values of other covariates in Models 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Multiple Logistic Regression of Cognitive Tests and Cervical Vestibular-Evoked Myogenic Potential (cVAMP) Test Amplitudes in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging

| Cognitive Test | Model 1 | Model2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P-Value | β | P-Value | |

| Mental status: MMSE | −0.16 | .24 | −0.32 | .03 |

| Visuospatial ability | ||||

| Card rotations | −8.60 | .003 | −11.5 | .001 |

| Purdue pegboard | ||||

| Dominant | −0.40 | .002 | −0.39 | .005 |

| Nondominant | −0.35 | .009 | −0.31 | .04 |

| Mean | −0.38 | .001 | −0.35 | .005 |

| Benton visual retentiontest, errors | −0.86 | .02 | −1.11 | .008 |

| Trail-making testpart A, seconds | −0.63 | .64 | −0.35 | .81 |

| Trail-making testpart B, seconds | −7.66 | .007 | −6.09 | .04 |

| Memory: California verbal learning test | ||||

| Immediate recall total | 0.02 | .98 | −2.00 | .07 |

| Delayed recall | −0.03 | .93 | −0.68 | .05 |

| Executive function | ||||

| Backward digit span | −0.11 | .36 | −0.21 | .13 |

| Category fluency, mean | 0.07 | .79 | −0.04 | .89 |

| Letter fluency, mean | −0.02 | .96 | −0.23 | .62 |

| Attention | ||||

| Forward digit span | −0.07 | .52 | −0.14 | .25 |

| Digit symbol substitution test | −0.12 | .83 | −0.56 | .55 |

| Factor analysis regressions | ||||

| Factor 1: visuospatial | −0.17 | .02 | −0.11 | .15 |

| Factor 2: verbal memory | −0.04 | .68 | −0.18 | .16 |

| Factor 3: working memoryand attention | −0.18 | .09 | −0.30 | .02 |

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, and education.

Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, cardiovascular risk factors, vision, and hearing.

Negative β coefficients indicate poorer cognitive function with decreasing cVEMP amplitude.

To assess the magnitude of difference in cognitive performance associated with poorer vestibular function, the difference in chronological age that would be equivalent to 1-μV lower cVEMP amplitude was estimated. The visuospatial cognitive tests that were significantly associated with age and vestibular function were considered for this analysis. A 1-μV lower cVEMP amplitude was equivalent to 8.5 additional years of age for performance on the Card Rotations test, an additional 3.5 years for the Purdue Pegboard test (mean), 10 years on the BVRT, and 6.7 years on the TMT B.

Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesis that vestibular functions mediate the association between age and cognitive performance. Models were specifically developed considering the tests with substantial visuospatial components, including the Card Rotations test, TMT B, BVRT, and the Purdue Pegboard (mean) test, as outcome variables in adjusted analyses. Vestibular function mediated 11% of the association between age and Card Rotations performance (Figure 1A), 11% of the association between age and TMT B time (Figure 1B), 12% of the association between age and BVRT errors (Figure 1C), and 5% of the association between age and Purdue Pegboard score (Figure 1D). The sample sizes used to test each of these models differed (N = 136 for Card Rotations test, N = 104 for TMT B, N = 133 for BVRT, N = 117 for Purdue Pegboard test).

Finally, exploratory factor analysis was used to identify latent cognitive abilities that underlie performance on the various cognitive tests. Only 73 individuals had complete data on all cognitive outcomes and contributed to the factor analysis. There was no significant difference between individuals with and without complete cognitive data in any demographic or cognitive measure with the exception of the Category Fluency test, on which scores were better in individuals with missing data than those with complete data (P = .02) (Online Appendix S2). Three factors were identified based on the parallel test. Based on the loading structure of the cognitive measures onto these three factors, the factors were defined as visuospatial ability, verbal memory, and working memory and attention. (For loadings see Online Appendix S3.) The visuospatial factor was significantly associated with cVEMP amplitude in Model 1 (P = .02) but not Model 2 (P = .15). The verbal memory factor was not significantly associated with cVEMP amplitude in either model. The working memory and attention factor was not significantly associated with cVEMP amplitude in Model 1 (P = .09) but was significantly associated in Model 2 (P = .02) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

These analyses offer compelling evidence of a cross-sectional association between vestibular and cognitive function. Vestibular function was associated with cognitive tests of visuospatial ability. This finding is consistent with an emerging literature showing that impairment in visuospatial tasks such as spatial navigation and spatial memory co-occurs with vestibular disorders, although the specific tests used in the BLSA differed from those used in prior studies.10,11,31 This study extends these prior observations of cognitive impairment in individuals with specific vestibular disorders and suggests that vestibular loss associated with aging may contribute to age-related variation in cognitive function. Findings from the factor analyses suggest that vestibular function may be associated with working memory and attentional function in addition to visuospatial ability.

The mechanism by which vestibular dysfunction is associated with cognitive dysfunction is unclear, although several potential pathways have been hypothesized. Loss of peripheral vestibular input may lead to atrophy of areas within the cortical vestibular network, including the “head direction cells” within the thalamus, subiculum, and entorhinal cortex; the temporoparietal junction; and the part of the hippocampus that contains “place cells.”12,32,33 Substantial convergence with visual streams of information occurs in these cortical sites, specifically in the hippocampus and medial superior temporal area.34–36 A study of 10 individuals with bilateral vestibular failure found that they developed significant hippocampal atrophy and associated impairments in visuospatial tasks such as navigation in a virtual maze.10 Another study in 22 individuals with bilateral vestibular loss found decreases in functional connectivity of temporoparietal junction structures critical for visuospatial processing and the rest of the brain.37

The association between vestibular and cognitive dysfunction may also relate to the influence of the vestibular system on working memory and attentional processes. A significant association was found in factor analyses between vestibular function and the working memory and attention factor, which chiefly included the Forward and Backward Digit Span tasks, which are tests of short-term memory. Studies in animals suggest that vestibular input is critical for spatial working memory, which is the short-term storage of spatial information for use in ongoing cognitive tasks.38,39 Spatial working memory centers are thought to reside in the hippocampus and the basal ganglia, and important vestibular-striatal connections are beginning to be recognized.40 A final mechanism that may link vestibular and cognitive function is common risk factors such as microvascular disease and hyperglycemia. The current study attempted to adjust for these potential confounding factors, although residual confounding cannot be definitively excluded.

In these analyses, the function of the saccule, the vestibular end organ that detects tilting of the head with respect to gravity, was specifically considered. Although the literature on the contribution of each of the vestibular end organs to cognitive function is sparse, studies suggest that the saccule may play a preeminent role in spatial cognition. In mice, animals with congenitally absent saccular function exhibit a head tilt phenotype.39 These mutant mice have been shown to have poorer ability to navigate through a radial maze than their wild-type counterparts. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of saccular stimulation in humans have shown activation of a broad cortical network, including the intraparietal sulcus, the temporoparietal junction, the paracentral lobule, and the cingulate cortex.41,42 Electroencephalographic studies in humans demonstrate that stimulation of the saccule through sound-evoked VEMPs activates a similar array of cortical structures, including the operculum and insular cortex around the temporoparietal junction.43 Saccular function is assessed routinely with the cVEMP as part of the standard battery of clinical vestibular tests, which also includes electronystagmography and caloric testing. Interventions to treat saccular dysfunction are lacking, largely because of the underrecognition of the importance of this organ. This study underscores the salience of the saccule to critical functions such as spatial cognition. If these observations are confirmed in a longitudinal analysis, it is possible that developing therapies to remediate saccular function may ameliorate the cognitive decline that many aging individuals experience.

Limitations of this study include the cross-sectional nature of the analyses, which cannot support causal inferences. The effects of confounding variables have been minimized by adjusting for potential predictors of cognitive dysfunction, including age, sex, race, educational level, visual acuity, hearing function, and cardiovascular risk factors in the analyses. Moreover, a causal association between loss of vestibular sensitivity and cognitive decline may be more plausible than the reverse, although recent work suggests bidirectional interactions whereby the cognitive state can influence vestibular responsivity.44 Additionally, almost one-quarter of participants had absent cVEMP responses and were not included in the analyses. These individuals were significantly older than participants with present responses, consistent with prior literature showing increasing loss of cVEMP responses with age.45 Exclusion of older individuals with greater levels of cognitive impairment may have led to an underestimate of effect sizes in this study. Furthermore, the sample size did not permit stratified analyses to evaluate potential effect modification of the association between vestibular and cognitive function, for example according to sex or race. Finally, less than half of the entire sample was included in factor analyses, given that only participants who completed all cognitive tests were included. Although participants with complete data did not differ substantially on demographic, clinical, or cognitive measures from those with missing data, the findings from the factor analyses need to be interpreted with caution given the smaller analytical sample.

A significant association was found between vestibular function and specific domains of cognitive function related to visuospatial ability and perhaps working memory and attention. Moreover, it was demonstrated that vestibular function is an important mediator of the association between age and cognitive decline. These findings have potentially profound public health implications, given the widespread and devastating effects of age-related cognitive decline on affected individuals and society. It has been hypothesized that vestibular loss contributes to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease,46 and a small study of 25 older adults observed a weak association between vestibular dysfunction and topographical memory impairment, one of the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease.47 Deterioration of visuospatial ability in older individuals may contribute to important geriatric outcomes such as falls, unintentional injury, inability to perform activities of daily living, and loss of independence. Future studies will need to establish whether mitigating age-related decline in peripheral vestibular sensitivity will forestall these highly morbid and costly outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Multiple Linear Regression Analyses of Cognitive Outcomes According to Vestibular Function and Other Covariates from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

Appendix S2. Demographic Characteristics and Cognitive Outcomes in Individuals with Missing Data and Those with Complete Data: Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

Appendix S3. Rotated Factor Loadings of Cognitive Tests: Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

Acknowledgments

Support was received from National Institutes of Health Grants NIDCD K23 DC013056 and 5T32 DC000023-30.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Bigelow, Semenov, Agrawal had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Bigelow, Ferrucci, Resnick, Agrawal. Analysis and interpretation of data: Bigelow, Semenov, Resnick, Xue, Agrawal. Drafting of manuscript: Bigelow, Semenov, Agrawal. Critical revision of manuscript: Bigelow, Semenov, Trevino, Ferrucci, Resnick, Simonsick, Agrawal.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Peterka RJ, Black FO. Age-related changes in human posture control: Sensory organization tests. J Vestib Res. 1990;1:73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welgampola MS, Colebatch JG. Vestibulocollic reflexes: Normal values and the effect of age. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1971–1979. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baloh RW, Enrietto J, Jacobson KM, et al. Age-related changes in vestibular function: A longitudinal study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;942:210–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, et al. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:938–944. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal Y, Davalos-Bichara M, Zuniga MG, et al. Head impulse test abnormalities and influence on gait speed and falls in older individuals. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:1729–1735. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318295313c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekvall Hansson E, Magnusson M. Vestibular asymmetry predicts falls among elderly patients with multi-sensory dizziness. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liston MB, Bamiou D-E, Martin F, et al. Peripheral vestibular dysfunction is prevalent in older adults experiencing multiple non-syncopal falls versus age-matched non-fallers: A pilot study. Age Ageing. 2014;43:38–43. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimm RJ, Hemenway WG, Lebray PR, et al. The perilymph fistula syndrome defined in mild head trauma. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1989;464:1–40. doi: 10.3109/00016488909138632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risey J, Briner W. Dyscalculia in patients with vertigo. J Vestib Res. 1990;1:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt T, Schautzer F, Hamilton DA, et al. Vestibular loss causes hippocampal atrophy and impaired spatial memory in humans. Brain. 2005;128:2732–2741. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidetti G, Monzani D, Trebbi M, et al. Impaired navigation skills in patients with psychological distress and chronic peripheral vestibular hypofunction without vertigo. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:21–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoder RM, Taube JS. The vestibular contribution to the head direction signal and navigation. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014;8:32. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, Goddard M, Darlington CL, et al. Bilateral vestibular deafferentation impairs performance in a spatial forced alternation task in rats. Hippocampus. 2007;17:253–256. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Age differences in spatial memory in a virtual environment navigation task. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:787–796. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffat SD, Resnick SM. Effects of age on virtual environment place navigation and allocentric cognitive mapping. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:851–859. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moffat SD, Elkins W, Resnick SM. Age differences in the neural systems supporting human allocentric spatial navigation. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adamo DE, Briceño EM, Sindone JA, et al. Age differences in virtual environment and real world path integration. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:26. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2012.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baccini M, Paci M, Del Colletto M, et al. The assessment of subjective visual vertical: Comparison of two psychophysical paradigms and age-related performance. Attent Percept Psychophys. 2014;76:112. doi: 10.3758/s13414-013-0551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen KD, Welgampola MS, Carey JP. Test-retest reliability and age-related characteristics of the ocular and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential tests. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:793–802. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181e3d60e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C, Zuniga MG, Nguyen KD, et al. How to interpret latencies of cervical and ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials: Our experience in fiftythree participants. Clin Otolaryngol. 2014;39:297–301. doi: 10.1111/coa.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson JR, De Fries JC, McClearn GE, et al. Cognitive abilities: Use of family data as a control to assess sex and age differences in two ethnic groups. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1975;6:261–276. doi: 10.2190/BBJP-XKUG-C6EW-KYB7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiffin J, Asher EJ. The Purdue pegboard: Norms and studies of reliability and validity. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:234–247. doi: 10.1037/h0061266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benton A. The Revised Visual Retention Test Clinical and Experimental Applications. Iowa City: State University of Iowa; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reitan R. Trail Making Test: Manual for Administration and Scoring. Tucson, AZ: Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, et al. California Verbal Learning Test, Research Ed. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spreen O. Neurosensory Center Comprehensive Examination for Aphasia (NCCEA), 1977 Revision: Manual of Instructions. Victoria, BC, Canada: Neuropsychology Laboratory, University of Victoria; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royer FL, Gilmore GC, Gruhn JJ. Normative data for the symbol digit substitution task. J Clin Psychol. 1981;37:608–614. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198107)37:3<608::aid-jclp2270370328>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal Y, Zuniga MG, Davalos-Bichara M, et al. Decline in semicircular canal and otolith function with age. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:832–839. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182545061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Candidi M, Micarelli A, Viziano A, et al. Impaired mental rotation in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and acute vestibular neuritis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:783. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dieterich M, Brandt T. Functional brain imaging of peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 10):2538–2552. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ventre-Dominey J. Vestibular function in the temporal and parietal cortex: Distinct velocity and inertial processing pathways. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014;8:53. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu Y, Watkins PV, Angelaki DE, et al. Visual and nonvisual contributions to three-dimensional heading selectivity in the medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci. 2006;26:73–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2356-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umarova RM, Saur D, Schnell S, et al. Structural connectivity for visuospatial attention: Significance of ventral pathways. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:121–129. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kravitz DJ, Saleem KS, Baker CI, et al. A new neural framework for visuospatial processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:217–230. doi: 10.1038/nrn3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Göttlich M, Jandl NM, Wojak JF, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity in patients with chronic bilateral vestibular failure. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;4:488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Besnard S, Machado ML, Vignaux G, et al. Influence of vestibular input on spatial and nonspatial memory and on hippocampal NMDA receptors. Hippocampus. 2012;22:814–826. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoder RM, Kirby SL. Otoconia-deficient mice show selective spatial deficits. Hippocampus. 2014;24:1169–1177. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stiles L, Smith PF. The vestibular–basal ganglia connection: Balancing motor control. Brain Res. 2015;1597:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyamoto T, Fukushima K, Takada T, et al. Saccular stimulation of the human cortex: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett. 2007;423:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlindwein P, Mueller M, Bauermann T, et al. Cortical representation of saccular vestibular stimulation: VEMPs in fMRI. NeuroImage. 2008;39:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kammermeier S, Singh A, Noachtar S, et al. Intermediate latency evoked potentials of cortical multimodal vestibular areas: Acoustic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;126:614–625. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staab JP, Balaban CD, Furman JM. Threat assessment and locomotion: Clinical applications of an integrated model of anxiety and postural control. Semin Neurol. 2013;33:297–306. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brantberg K, Granath K, Schart N. Age-related changes in vestibular evoked myogenic potentials. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12:247–253. doi: 10.1159/000101332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Previc FH. Vestibular loss as a contributor to Alzheimer’s disease. Med Hypotheses. 2013;80:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Previc FH, Krueger WW, Ross RA, et al. The relationship between vestibular function and topographical memory in older adults. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014;8:46. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Multiple Linear Regression Analyses of Cognitive Outcomes According to Vestibular Function and Other Covariates from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

Appendix S2. Demographic Characteristics and Cognitive Outcomes in Individuals with Missing Data and Those with Complete Data: Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

Appendix S3. Rotated Factor Loadings of Cognitive Tests: Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.