Abstract

Synchronization of oscillations among brain areas is understood to mediate network communication supporting cognition, perception and language. How task-dependent synchronization during word production develops throughout childhood and adolescence, as well as how such network coherence is related to the development of language abilities, remains poorly understood. To address this, we recorded magnetoencephalography (MEG) while 73 participants aged 4 – 18 years performed a verb generation task. Atlas-guided source reconstruction was performed, and phase synchronization among regions was calculated. Task-dependent increases in synchronization were observed in the theta, alpha and beta frequency ranges, and network synchronization differences were observed between age groups. Task-dependent synchronization was strongest in the theta band, as were differences between age groups. Network topologies were calculated for brain regions associated with verb generation, and were significantly associated with both age and language abilities. These findings establish the maturational trajectory of network synchronization underlying expressive language abilities throughout childhood and adolescence, and provide the first evidence for an association between large-scale neurophysiological network synchronization and individual differences in the development of language abilities.

Keywords: neural synchrony, neural oscillation, language development, functional connectivity, magnetoencephalography

Introduction

Within the first few years of life, children acquire the ability to comprehend thousands of words. It has been demonstrated that after 18 months, there is an acceleration in vocabulary learning that is associated with a phase of rapid myelination in temporofrontal language regions of the brain (Pujol et al., 2006). By age three years, typically developing children reliably call upon canonical brain regions known to be involved in speech and language perception, or receptive language (Redcay et al., 2008). Despite these early gains, receptive language ability follows a protracted developmental trajectory (Berl et al., 2010) with evidence that story comprehension is not fully mature until young adulthood (Szaflarski et al., 2012). However, in adults, the brain regions involved in receptive language are well understood (for reviews, see Price 2010; Price 2012). As well, the structural and functional connectivity within the language comprehension network have been extensively investigated (for reviews, see Dick & Tremblay 2012; Friederici 2011; Turken & Dronkers 2011).

Expressive language processing is more complicated. While the brain regions involved in speech and language production have been identified (Price 2010; Price 2012; Scott 2012), the networks involved are complex and encompass many levels of cortical control (Guenther et al., 2006). For example, successful word production includes cognitive processes such as lexical access and word retrieval, as well as the control of motor systems and sensory feedback loops. Classic fMRI studies of expressive language have identified a brain system situated primarily in left frontal lobe structures that is evidenced in adults (Pujol et al., 1999; Van der Kallen et al., 1998; for reviews, see Price 2010; Price 2012) and children (Friederici 2006; Gaillard et al., 2000; Hertz-Pannier et al., 1997). Studies of expressive language development accordingly have often focused on maturational shifts occurring within local brain structures (Holland et al., 2007; Kadis et al., 2011; Szaflarski et al., 2006). More recent models of language function in the brain, however, have emphasized the importance of integration within distributed networks of brain regions (i.e. Hickok & Poeppel 2004; Indefrey & Levelt 2004; Golfinopolos et al., 2010). This has paralleled a more general trend toward understanding the function of brain regions with respect to interactions among coactive areas, rather than proscribing specific localizable functions to spatially restricted areas of the brain (McIntosh 2000). However, the only investigation into expressive language networks in children has focused on network lateralization (Vannest et al., 2009) and not network coherence. Knowledge remains scant regarding the development of functional connectivity within the expressive language network.

The synchronization of neural oscillations among brain regions has been associated with task-dependent network communication supporting cognition and perception across diverse contexts (Varela et al., 2001, Uhlhaas et al., 2009a) as synchronized neuronal assemblies can more effectively coordinate information transfer (Fries 2005). Modulation of neural oscillations, and their coordination across brain areas, have been linked to expressive language, receptive language, and the interactions between language networks and brain regions mediating other cognitive and perceptual abilities (i.e. Bastiaansen et al., 2005; Bedo et al., 2014; Bögels et al., 2014; Doesburg et al., 2008, 2012; Ewald et al., 2012; Hermes et al., 2014; Mellem et al., 2013; Piai et al., 2013; Weiss & Mueller 2012), and local neural oscillations have been related to the encoding of speech sounds as well as the development of language abilities during infancy and early childhood (Benasich et al., 2008; Gou et al., 2011). Whether inter-regional coherence changes throughout childhood and adolescence, as well as if such changes are related to the development of language abilities, remains unknown.

In the present study, we recorded magnetoencephalographic (MEG) data during the performance of an overt verb generation task in a large series of 73 participants aged 4 – 18 years. Psychometric data reflecting language abilities and overall intellectual function were also collected. We tested the hypotheses that expressive language performance was supported by increased phase coherence within distributed neural networks encompassing brain regions associated with expressive language function, that network topologies of expressive language regions would develop with age, and that these network topologies would be associated with language abilities.

Methods

Participants

Seventy three participants (42 female; 31 male) were recruited as part of an ongoing study examining the development of the neural control of word production. Participants ranged in age from 4 – 18 years and included 24 young children (4 – 9 years), 20 older children (10 – 13 years), and 29 adolescents (14 – 18 years). These groupings were based on established knowledge regarding the timing of cognitive developmental changes and stages. At the lower cut-off of age 4, typically developing children speak clearly, fluently and have a good grasp of language (Brown, 1973). At age 10, there is a transition into early adolescence that is marked by physical, cognitive and social changes, and at age 14, there is a transition into middle adolescence (Hartzell, 1984). In neuroimaging studies, large population studies have set the precedent for similar groupings (for example, O’Muircheartaigh et al., 2013 for the young children group, Vannest et al., 2009 for the two older groups). Participants were selected to be right-handed, as confirmed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (mean = 75.2; SD = 16.2; Oldfield, 1971). All participants spoke English as their dominant language and were in the age-appropriate grade at school. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were excluded if they had a prior history of neurological, audiological, speech-language or psychiatric abnormalities, or had contraindications for MEG or MRI neuroimaging. This study was approved by The Hospital for Sick Children Research Ethics Board, and all participants or their parents gave informed written consent.

Overt verb generation paradigm

During MEG recordings, participants performed an overt verb generation task in English. This paradigm has been described previously and has been successfully employed for mapping language related brain activity in children and adolescents (see Kadis et al., 2011) and validated against fMRI (Pang et al., 2011). In this protocol, participants were visually presented with images of common objects and were required to overtly generate verbs associated with those objects. Participant’s responses were monitored to ensure engagement in the task. Stimuli were presented for 4.6 +/− 0.2 seconds followed immediately by the next image. Stimulus objects were developed in consultation with standardized language batteries and normative studies (e.g., Bird et al., 2001; Cycowicz et al., 1997; Snodgrass & Vanderwart 1980) so that all objects would be familiar to 4 year old children. The paradigm included 81 stimulus trials. This paradigm has previously been demonstrated to reliably elicit neuromagnetic activity related to expressive language processing in participants across the age range investigated in the present study (Kadis et al., 2011). As this paradigm was designed to robustly elicit language-related activation across a wide range of age and function, task-performance is not a good measure of language abilities due to ceiling effects. For this reason, behaviour was monitored to ensure that subjects remained on task, but psychometric data were used instead of task performance to index individual differences in ability.

Neuroimaging data acquisition

MEG data were recorded during the verb generation task using a 151 channel whole-head CTF MEG system (Port Coquitlam, Canada). Data were digitized at 4000 Hz and stored offline for analysis. Head position was recorded continuously at 30Hz to ensure that all analyzed participants were within tolerable movement ranges (< 5 mm, consistent with established standards for movement control in the field). In the event that a child moved > 5 mm, their data were discarded and re-recorded. Children were given instructions, practice trials and feedback to stay still. As well, their heads were well-padded with foam inside the dewar. All data used in these analyses have motion < 5 mm. To ensure that the age-related neural differences seen in this study were due to language production processes and not an artifact induced by greater jaw and head movement in the younger age groups during MEG recording, we performed a preliminary analysis on head motion data in a subset of our cohort. We measured head movement, specifically head displacement in the z-axis (superior-inferior), which could be related to the up-down motion of the jaw, on a trial-by-trial basis (115 trials), as children spoke the syllable /pa/. We tested a group of fifteen 6–7 year olds and fifteen 18–20 year olds and found that mean movement for the younger group was 2 mm ± 0.5SD and in the older group, it was 0.3 mm ± 0.05SD. In both cases, these values are well below the accepted threshold of 5 mm, and demonstrate that effects seen in this study are likely due to real neural changes and not an artefact of word production. To facilitate co-registration of functional brain data with neuroanatomy, as well as to create accurate individualized head models for source reconstruction, volumetric MRI scans were collected from each participant (T1 weighted 3D MPRAGE) using an 3.0 T MRI system (Siemens, Munich, Germany). Co-registration of MEG and MRI data was facilitated using fiducial markers placed at the nasion as well as the left and right preauricular points.

Psychometric data collection

Following neuroimaging data collection, psychometric evaluations were carried out for each participant to measure both verbal and non-verbal abilities. Verbal abilities, specifically expressive and receptive language, were measured using the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT; Williams 1997), and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 1997). The EVT is a standardized test of vocabulary where the examiner points to objects or pictures of objects which the subject is required to name, and similarly, the PPVT is a self-paced test of receptive vocabulary test where children are shown a set of four pictures and they are required to point to the picture that matches the word name spoken by the examiner. In addition to verbal ability, general intellectual ability was indexed by the Weschler Non-Verbal test (WNS; Weschsler & Naglieri 2009). All of the above psychometric measures were normed for age, such that higher scores denote more advanced abilities for a subject’s age.

MEG source reconstruction

In the present study we adopted a seed-based approach, wherein broadband time-series representing the activity of all 90 cortical and subcortical regions in the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) are included. This source solution provides good coverage and has been successfully used in the study of functional connectivity in distributed networks (He et al., 2009; Liao et al., 2010; Supekar et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009); including studies using MEG (Diaconescu et al., 2011; Doesburg et al., 2013a, 2013b). Coordinates were unwarped from standard MNI space to corresponding locations in each individual’s head space using SPM2. Data were downsampled to 667 Hz for analysis, and broadband (1 – 150 Hz) time series were reconstructed from each source using a scalar beamformer (Cheyne et al., 2006), which has been successfully employed in an atlas-guided analysis of task-dependent MEG activity (Diaconescu et al., 2011) and is effective for removal of ocular and non-ocular artefacts from reconstructed time series (Cheyne et al., 2007). To facilitate accurate forward projection of signals from source space, a multisphere head model was created for each participant using their individual MRI (Lalancette et al., 2011).

Inter-regional phase coherence

Data were filtered into the classic neurophysiological frequency ranges of theta (4 – 7 Hz), alpha (8 – 14 Hz) and beta (15 – 30 Hz). We focused on connectivity in these frequency ranges as inter-regional theta and alpha-band synchronization are understood to mediate large scale network interactions, whereas gamma oscillations are increasingly thought to primarily be relevant for local neuronal activity (see von Stein & Sarnthein 2000; Palva & Palva 2007 for reviews), and moreover are more susceptible to contamination by artefacts in studies of task-dependent oscillatory dynamics (i.e. Yuval-Greenberh et al., 2008). More recent evidence has indicated that beta oscillations may also be pertinent for integrating local activity, mediated by gamma rhythms, into large-scale networks (Donner & Siegel 2011; Siegel et al., 2012). Time series of instantaneous phase values were derived for each epoch, frequency band, and subject using the Hilbert transform. This produced time series of instantaneous amplitude and instantaneous phase values for each trial, source and frequency band. Amplitude time series were averaged across trials for analysis of task-dependent modulations of amplitude. Task-dependent connectivity dynamics were then determined for each analyzed frequency band using the phase lag index (PLI), which measures the consistency of inter-regional phase relationships across trials, for a given pair of regions and frequency band, and removes/attenuates phase synchrony occurring at zero/near-zero phase lag, thereby providing protection against spurious synchronization occurring from common sources (Stam et al., 2007). This produced, for each subject and frequency band, a 90-by-90 adjacency matrix at each time point. Animations of the evolution of matrices over time, as well as time series of average network connectivity (averaged over all analyzed source-pairs), were used to visualize connectivity dynamics and determine time windows bracketing peaks in task-dependent inter-regional phase locking for further analysis.

Network connectivity analysis

To characterize task-dependent changes in inter-regional phase locking for each frequency band, adjacency matrices were averaged across time points throughout identified connectivity ‘peaks’ (see above). Baseline adjacency matrices were obtained by averaging across an identical number of data points in the pre-stimulus interval. Connectivity differences between active and baseline windows were evaluated using the Network Based Statistic toolbox (NBS; Zalesky et al., 2010). This approach first applies a univariate statistical threshold (T-statistic) to each element in the connectivity matrix and identifies the size of interconnected components. Group membership was then shuffled and the largest component size observed in this surrogate data was recorded. This surrogation process was repeated 5000 times to establish a null distribution, and the size of ‘real’ observed connectivity components was plotted in the surrogate distribution to evaluate statistical significance. The NBS approach requires the manual (and somewhat arbitrary) assignment of a T-statistic for the initial univariate threshold (Zalesky et al., 2010). Since the identical threshold is applied to both the real and surrogated data, protection against false positives due to multiple comparisons is provided at any threshold (see Zalesky et al., 2010, 2012). As selection of the threshold value could potentially impact the observed pattern of results, however, we systematically varied the initial threshold parameter and observed the effect on the results of NBS. A more comprehensive description of the NBS statistical approach is provided by Zalesky et al., 2010.

A similar approach was used to evaluate network connectivity differences between age groups. Here, baseline adjacency matrices were subtracted from active window adjacency matrices for each subject. NBS was then used to evaluate the statistical reliability of network connectivity differences between age groups. As for the analysis of task-dependent connectivity changes, we systematically varied the initial univariate T-statistic threshold and observed its impact of the NBS results, for each frequency band. Network connectivity statistics were calculated using the NBS toolbox (Zalesky et al., 2010) and the results were visualized using BrainNet Viewer (Xia et al., 2013).

Analysis of network topology for identified expressive language regions

Brain regions involved in task-dependent changes in network connectivity, as well as connectivity differences between age groups, were inspected for brain areas known to be associated with expressive language functions (see Hickok & Poeppel 2004; Indefrey & Levelt 2004; Golfinapolos et al., 2010 for reviews). For regions indentified in this manner, graph theoretical analysis was used to derive network topologies, which characterize their involvement in large-scale task-dependent brain networks (see Bullmore & Sporns 2009). Graph properties for these regions were calculated using the Brain Connectivity Toolbox (Rubinov & Sporns 2010). To evaluate network topologies for these regions we chose the graph theoretical measures of strength and clustering, which were computed from the 90-by-90 weighted, undirected PLI adjacency matrices reflecting differences in connectivity between active and baseline periods. Strength reflects how functionally connected a given region is to other regions in the analyzed network, whereas clustering represents the functional embeddedness of a region in a network (Onnela et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2008). Graph measures representing network engagement of brain areas associated with expressive language were used to test the hypotheses that the topologies of these regions are associated with individual differences in language ability, and that the engagement of these regions in language related network connectivity develops throughout childhood and adolescence.

Results

Inter-regional phase synchronization during overt verb generation

Inspection of inter-regional connectivity dynamics revealed distinct peaks in theta, alpha, and beta bands indicating task-dependent phase synchronization (Figure 1a). In the theta band, increased synchronization (see Figure 1b for adjacency matrix at a representative time point) was observed within the first 500 ms following stimulus presentations (Figure 1c), in higher frequencies this was more transient, being observed during the first 250 ms in the alpha-band, and only during the first 190 ms in the beta-band. These time courses of global network synchronization where used to define active and passive windows for each analyzed frequency band, for example, in the theta band adjacency matrices representing mean connectivity for each connection in the first 500 ms following stimulus onset were compared with adjacency matrices reflecting mean in the 500 ms interval preceding stimulus onset. NBS analysis indicated that increased network synchronization was stable across numerous thresholds for each analyzed frequency band with a predictably declining number of significant edges as the initial univariate threshold was increased (Figure 1a). NBS analysis did not reveal significant patterns of reduced network synchronization in the active window, relative to the baseline interval.

Figure 1. Inter-regional synchronization during verb generation.

A) Number of significant edges (inter-regional connections which were more connected in the active window, relative to the baseline) for each analyzed frequency range as a function of T-statistic NBS thresholds for all analyzed participants. Note that task-dependent increases in connectivity are strongest in the theta frequency range. B) Connectivity matrix for the theta-band at a representative time point (warm colours denote higher synchrony) for all 90 cortical and subcortical seed regions, averaged across all analyzed participants. C) Time course of theta connectivity during the verb generation task.

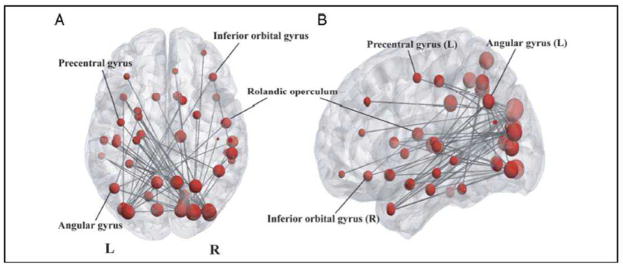

Task-dependent network connectivity increases were strongest in the theta-band, as at each analyzed threshold more statistically significant edges were observed. Increases in theta connectivity were also observed at higher thresholds than any other frequency range. Increased task-dependent connectivity in the theta-band is shown at a representative threshold (T = 7.5) in Figure 2. Task-dependent phase locking was not observed in the alpha or beta bands at this threshold. This network encompassed numerous task-relevant brain regions, including areas of visual cortex responsible for stimulus processing and regions implicated in expressive language function. In particular, the left angular gyrus, left precentral gyrus, right inferior orbital gyrus and right Rolandic operculum were included in this theta-band connectivity component which reflects task-dependent increases in oscillatory coherence among distributed brain regions. Task dependent phase locking in alpha and beta bands was more topographically restricted, and primarily involved brain areas associated with visual processing suggesting that network coherence at these frequencies may pertain more to the processing of the stimulus than to language-related task demands. Accordingly, we focus primarily on theta connectivity.

Figure 2. Increased theta-band synchrony during expressive language processing.

Increased connectivity is shown in A) axial and B) left sagittal orientations at a representative threshold (T = 7.5). Lines indicate significant task-dependent connectivity increases among regions and the size of each region denotes task-dependent increases in connectivity strength.

Development of network connectivity associated with expressive language processing

Analysis of group differences in inter-regional phase locking revealed statistically reliable differences in theta and alpha frequency ranges (Figure 3). Group differences were strongest in the theta-band as more significant edges were identified at all analyzed thresholds, and statistically reliable differences were observed at higher thresholds for theta than for other analyzed frequency bands. Network connectivity differences were strongest for the comparison of adolescents with young children. Figure 4 depicts group differences in task-dependent theta connectivity at a representative threshold (T = 3.5), at which no significant differences were observed in other analyzed frequency ranges. Unlike the overall pattern of task-dependent theta connectivity, which included many connections involving visual cortex and likely reflected transfer of visual information to higher-order task-relevant regions including language areas, differences between age groups expressed a pattern of connectivity differences less anchored in visual cortex. Group differences involved increased connectivity involving numerous frontal and temporal regions, including areas which have been implicated in language processing. Specifically, increased theta connectivity incorporating left angular gyrus and right insula was observed for the older children, relative to the younger children. Comparison of the adolescent age group with the early childhood group revealed theta connectivity differences involving a much larger set of language-related areas including left and right supramarginal gyrus, left and right precentral gyrus, left angular gyrus, left frontal inferior operculum, right insula, right inferior triangularis, and right frontal inferior orbital gyrus. No group differences in task-dependent theta connectivity were observed between the older children and the adolescents, and no increases in theta connectivity were observed for younger age groups, relative to older age groups. These results indicate that the developmental changes in network engagement during overt verb generation primarily pertains to network involvement of frontal regions, including regions implicated in expressive language functions (Hickok & Poeppel 2004; Indefrey & Levelt 2004; Golfinapolos et al., 2010; Figure 4).

Figure 3. Differences between age groups in network connectivity dynamics.

The number of significant inter-regional connections, as a function of T-statistic NBS threshold, for comparison of A) young children with older children, and B) young children with adolescents. As was observed for task-dependent connectivity increases, group differences are strongest in the theta frequency range.

Figure 4. Age-dependent increases in network connectivity during verb generation.

Significant increases in axial and left sagittal orientations at a representative NBS threshold (T = 3.5) for A) young children compared with older children, and B) young children compared with adolescents. Lines indicate significant task-dependent connectivity increases among regions and the size of each region denotes task-dependent increases in connectivity strength. No significant differences between older children and adolescents at this threshold.

Network topologies of expressive language regions associated with development and verbal abilities

To investigate the hypothesis that network topologies are associated with individual differences in the development of verbal abilities, we calculated the graph theoretical measures of strength and clustering for regions known to be associated with expressive language function (see Hickok & Poeppel 2004; Indefrey & Levelt 2004; Golfinapolos et al., 2010) identified in the NBS analysis as showing task-dependent connectivity increases in the theta-band (see Figure 2), and/or regions that showed differential theta-band connectivity in the age-group contrast (see Figure 4). We focused primarily on theta band connectivity in correlations with age and psychometric scores as this frequency range showed the most pronounced task modulation along with the strongest differences in the comparisons across age groups. Specifically, we investigated associations between age, verbal abilities and network topologies (strength and clustering) for the left inferior operculum, the left inferior orbital gyrus, the left supramarginal gyrus, and the left angular gyrus.

Age-related changes in task-dependent network topology were observed in the theta-band in the left inferior operculum (clustering, R = 0.31, p = 0.007), the left inferior orbital gyrus (strength, R = 0.26, p = 0.03; clustering, R = 0.30, p = 0.009), the left supramarginal gyrus (strength, R = 0.33, p = 0.004; clustering, R = 0.36, p = 0.002), and the left angular gyrus (strength, R = 0.32, p = 0.005; clustering, R = 0.37, p = 0.001). Associations between age and theta-band network topologies are depicted in Figure 5 (strength in the left column and clustering in the right). Significant associations between age and network topologies were also observed for the alpha frequency range, but only for the left angular gyrus (strength, R = 0.27, p = 0.002; clustering, R = 0.28, p = 0.017). No significant associations were observed between age and task-dependent network topologies in the beta band.

Figure 5. Developmental trajectory of dynamic network topologies in language regions.

Task dependent increases in the graph properties connectivity strength and clustering co-efficient become stronger with age. The left column shows associations between age and connectivity strength right column depicts associations between age and clustering.

Task-dependent network topologies in areas known to be associated with expressive language were also positively correlated with verbal abilities. Theta band connectivity involving the left inferior orbital gyrus was associated with higher PPVT scores (strength, R = 0.26 p = 0.03; clustering, R = 0.25, p = 0.04), as were network topologies involving left supramarginal gyrus (strength, R = 0.26, p = 0.03; clustering, R = 0.26, p = 0.03). See Figure 6 for scatterplots of the association between theta-band topologies and verbal abilities. Alpha-band strength was positively associated with PPVT scores in the left inferior orbital gyrus (R = 0.32, p = 0.008), and network topologies were also associated with both EVT (strength, R = 0.28, p = 0.02; clustering, R = 0.29, p = 0.02) and PPVT (strength, R = 0.28, p = 0.02; clustering, R = 0.31, p = 0.01) scores in the left supramarginal gyrus. Correlations between beta network topologies and verbal abilities were only bound with EVT scores in the left supramarginal gyrus (strength, R = 0.26, p = 0.03; clustering, R = 0.28, p = 0.03).

Figure 6. Network topologies of language areas associated with language abilities.

Higher task-dependent clustering coefficient and connectivity strength in canonical language regions is associated with increased verbal abilities as measured by the PPVT.

Regional activation, development and verbal abilities

We investigated associations between task-dependent changes in local amplitude, age and individual differences in verbal abilities, as local neuromagnetic activity has been shown to be relevant for expressive language processing elicited during verb generation (i.e. Kadis et al., 2011). To facilitate comparison with the connectivity results and maintain the focus of the study, we concentrated on the theta band and the language regions identified using the NBS method for task-dependent increases in connectivity, as well as age-group differences in task-dependent theta-band network synchronization. Briefly, analysis of network-wide modulation of theta activity (obtained by averaging theta amplitude at each time point across all 90 analyzed seed regions) indicated an increase in theta amplitude during task performance. To analyze associations between age, ability and amplitude, we subtracted the mean baseline theta amplitude, for each analyzed source, from the mean active window theta amplitude (using the same time and frequency windows employed in the connectivity analysis). Older age was associated with greater theta activation in the right inferior orbital gyrus (R = 0.32, p = 0.006), the right Rolandic operculum (R = 0.24, p = 0.04) and the right insula (R = 0.27, p = 0.02). Associations between task-dependent theta amplitude increases and EVT scores were observed for the right inferior orbital gyrus (R = 0.27, p = 0.02), as well as between theta activation and PPVT and right Rolandic operculum (R = 0.25, p = 0.03) and the left anterior cingulate (R = 0.27, p = 0.02).

Discussion

Using an atlas-guided MEG connectivity analysis approach, we demonstrate increased inter-regional synchrony during an expressive language task, namely picture verb generation. This task-dependent network synchronization was observed in theta, alpha and beta frequency ranges. Increased connectivity was most pronounced in the theta frequency range. This increased network synchronization strongly involved connectivity between areas of visual cortex and widespread areas of visual cortex, consistent with prior neuromagnetic studies of connectivity involving processing of a visual stimulus and using similar methods (i.e. Bangel et al., 2014; Leung et al., 2014) and encompassed brain areas including classic regions associated with language functions (i.e., Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas). Using graph theoretical analysis to analyze network topologies, we provide the first evidence for a maturational trajectory, throughout childhood and adolescence, for the recruitment of expressive language regions into large scale ensembles of coherently oscillating neurons. Moreover, we establish for the first time that task-dependent network connectivity involving brain areas implicated in expressive language function is associated with verbal language abilities.

Phase synchronization of neural oscillations is understood to be a general mechanism for dynamically coordinating communication among distributed neural populations (Fries 2005; Varela et al., 2001). Task-dependent increases in inter-regional synchronization have been associated with numerous cognitive processes (see Uhlhaas et al., 2009a; Palva et al., 2012 for reviews) including both expressive and receptive language (Doesburg et al., 2008, 2012) and letter processing (Herdman, 2011). Presently, we establish the normative developmental trajectory of inter-regional network synchronization throughout childhood and adolescence. Consistent with the results of the present study, low-frequency oscillations such as those in the theta-band are thought to be particularly relevant for long-range interactions (von Stein & Sarnthein 2000). Recent research has indicated that coupling between theta and gamma oscillations is also relevant for encoding of speech (Giraud & Poeppel 2012), which is intriguing as theta/gamma interactions have also been proposed to play a more fundamental role in functional cortical activation and inter-regional communication (Canolty et al., 2001; Canolty & Knight 2010; Lisman & Jensen 2013). This view is supported by recent EEG evidence from infants, which indicates that the extraction and integration of acoustic information on different time scales may be decoded by theta and gamma band oscillations in the auditory system (Musacchia et al., 2013).

Neural oscillations and their coordination among brain regions are thought to be relevant for the development of cortical networks throughout childhood and adolescence (Uhlhaas et al., 2010). Indeed, protracted maturational shifts in the expression of long-range EEG synchronization during coherent visual perception have been reported (Uhlhaas et al., 2009b). Age-related changes in resting state neural synchronization have been observed (Boersma et al., 2011, 2013), and developmental changes in task-dependent modulation of local oscillations have been previously described (Clarke et al., 2001). Maturational changes in spontaneous local EEG gamma oscillations during infancy and early childhood are associated with the development of language abilities (Benasich et al., 2008; Gou et al., 2011). The present study builds on such work by establishing, for the first time, age-related changes in neuronal network synchronization in language processing.

The present study found that inter-regional phase synchronization in the theta frequency range was particularly relevant for expressive language processing, consistent with prior research indicating that theta oscillations are highly relevant for language function. Increased theta connectivity has been previously reported during language production (Ewald et al., 2012), and modulation of theta power has also been related to expressive language (Hermes et al., 2014; Piai et al., 2014). Distributed theta-band network synchronization has also been reported during word reading (Bedo et al., 2014), indicating that theta oscillations are also relevant for network integration during receptive language processing as well. Moreover, recent evidence indicates that theta rhythms are pertinent for task dependent interactions between language networks and regions mediating other related functions. Modulation of theta oscillations and their inter-regional coherence has been related to mentalizing during language processing (Bögels et al., 2014). Increased anterior-posterior theta coherence has also been related to task dependent interactions between semantic processing and working memory (Mellem et al., 2013), and increased theta power during lexical-semantic retrieval (Bastiaansen et al., 2005). Such findings are congruent with our observation of synchronization of language-relevant regions with distributed brain regions in a verb generation tasks requiring coordinated activity of brain regions responsible for visual perception, object recognition, semantic retrieval, productive language and motor control.

The current study establishes the first evidence of source-resolved inter-regional coordination of oscillations in brain networks demonstrates the association with individual differences in verbal abilities. Previously, it has been demonstrated that lateralization of MEG sensor coherence in the theta band was associated with language performance in young children (Kikuchi et al., 2011). Moreover, preservation of this sensor-level coherence was found to be related to language abilities in young children with autism spectrum disorder, suggesting that development of typical network connectivity dynamics is linked with preservation of language abilities in clinical child populations (Yoshimura et al., 2013). Prior research employing an approach similar to that of the current study, source-resolved MEG phase synchronization analysis, demonstrated that individual differences in large-scale network synchronization were able to predict individual differences in working memory capacity in adults (Palva et al., 2010). Both local neuronal oscillations and inter-regional coherence in spontaneous EEG recordings have also been associated with individual differences in intelligence in adults (Langer et al., 2012; Thatcher et al., 2007, 2008). A recent study of twins demonstrated that individual differences in visually induced gamma oscillations were strongly genetically regulated (van Pelt et al., 2012). This suggests that individual genetic variance leading to heritable neurophysiological traits may contribute to differences in intelligence between individuals. From this perspective, our findings may suggest that heritable neurophysiological differences relevant for the brain’s ability to coordinate information flow in specific networks may be associated with individual differences in the development of cognitive and language abilities.

This work is an extension of prior research into brain development underpinning the maturation of language abilities. Imaging of structural connectivity has demonstrated that cortico-cortical language connections are already lateralized in children (Broser et al., 2012). Moreover, atypical development of white matter connectivity has been linked to language difficulties in populations of children born very prematurely (i.e. Feldman et al., 2012). Such relationships between structure and function may be due to the established interplay between the development of structural connectivity and the maturation of functional activation in language systems (Brauer et al., 2011). Age-related changes in the activation of language regions, measured using fMRI, have previously been identified and associated with language abilities (Lidzda et al., 2011). Developmental changes in MEG activation, such as increasing lateralization with age, have also been reported (Ressel et al., 2008). Moreover, fluctuations in verbal intelligence during adolescence have been linked to regional gray matter changes in motor speech areas, but not brain regions unrelated to language (Ramsden et al., 2011). The current findings uniquely extend beyond the extant literature by providing the first evidence that neurophysiological network synchronization during expressive language processing changes throughout childhood and adolescence, and that task-dependent network synchronization is associated with individual differences in verbal abilities.

To complement the connectivity analyses, we also investigated relations between task-dependent modulations of theta activity and language regions identified in the NBS analyses and verbal abilities. We found that increased theta activity in some language regions was associated with older age, and in a different subset of regions, increased task-dependent theta amplitude was associated with better verbal abilities. Importantly, the pattern of results linking theta connectivity, age and ability differed from relations between regional amplitude modulation, age and ability. This suggests that inter-regional interactions and regional recruitment of theta rhythms are distinct but inter-related processes. A related issue is that, although beamformer source reconstruction and PLI both offer protection from spurious interactions to common sources, spurious interactions could nonetheless arise from changes in the number of common sources or their power (Schoffelen and Gross, 2009, Stam et al., 2007).

Limitations

A limitation of the present study was the lack of behavioural data during the verb generation task. This paradigm was chosen as it is robust for eliciting language related brain activity across the age range in our study. Although subjects were monitored to unsure they were engaged in the task, performance data were not acquired and stored. This precluded formal assessment of age group differences in task performance, as well as investigation of relations between task-dependent network synchronization and task performance.

Another limitation pertains to the relation between group differences in task-dependent connectivity and coinciding modulations of regional activation. In this study, we used a combination of beamformer source reconstruction and PLI in an effort to provide maximal protection against spurious synchronization. Although this represents current best practice in the field, it is important to note that such methodological approaches cannot unambiguously differentiate true neural synchronization from spurious effects due to changes in activation. For example, changes in regional activity can influence factors such as signal-to-noise ratio which can impact on connectivity metrics such as PLI. The modulations of regional theta activity did not follow a spatial pattern that corresponded to the connectivity results; however, the findings of the present study should be interpreted with some caution due to the inability to separate the effects of activation from inter-regional phase synchronization with complete certainty. Future research will employ language paradigms with more multiple trial conditions which would increase the potential to enable closer matching of activation magnitudes.

Conclusion

The present study uniquely demonstrates the maturational trajectory of network synchronization during expressive language processing. We also provide the first evidence that engagement of brain regions associated with expressive language function in distributed oscillatory networks is associated with individual differences in verbal abilities. These findings expand present knowledge on the development of synchronization in brain networks and indicate that such task-dependent connectivity is associated with specific cognitive abilities. This cross-sectional study provides a foundation for understanding the role of network synchronization in typical cognitive development, as well as for understanding the biological basis of neurodevelopmental disorders with language and communication difficulties. Future research should investigate longitudinal changes in network synchronization during language processing and their relation to development of linguistic abilities across time, as well as how specific alterations in the ability to recruit coordinated neurophysiological activity during language processing may contribute to domain-specific difficulties in neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Annette Ye and Simeon Wong for their help with data analysis on this project. We would like to thank Anna Oh, Gordon Hua, Sarah Vinette and Marc Lalancette for their help with data acquisition, and Dr. Darren Kadis for the stimulation paradigm. As well, we thank the children and families for their participation. This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grants (MOP-89961) to EWP and (MOP-136935) SMD, as well as an NSERC grant to SMD (RGPIN-435659).

References

- Bastiaansen MCM, van der Linden M, ter Keurs M, Dijkstra T, Hagoort P. Theta responses are involved in lexical-semantic retrieval during language processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2005;17(3):530–541. doi: 10.1162/0898929053279469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangel KA, Batty M, Ye AX, Meaux E, Taylor MJ, Doesburg SM. Reduced beta band connectivity during number estimation in autism. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014;6:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedo N, Ribary U, Ward LM. Fast dynamics of cortical functional and effective connectivity during word reading. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benasich AA, Gou Z, Choudhury N, Harris KD. Early cognitive and language skills are linked to resting frontal gamma power across the first three years. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195(2):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berl MM, Duke ES, Mayo J, Rosenberger LR, Moore EN, VanMeter J, Ratner NB, Vaidya CJ, Gaillard WD. Functional anatomy of listening and reading comprehension during development. Brain Lang. 2010;114(2):115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Rao SM, Hammeke TA, Frost JA, Bandettini PA, Jesmanowicz A, Hyde JS. Lateralized human brain language systems demonstrated by task subtraction functional magnetic resonance imaging. Archives in Neurology. 1995;52(6):593–601. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540300067015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird H, Franklin S, Howard D. Age of acquisition and imageability ratings for a large set of words, including verbs and function words. Behaviour Research Methods, Instruments Computers. 2001;33(1):73–79. doi: 10.3758/bf03195349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma M, Smit DJ, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Stam CJ. Growing trees in child brains: graph theoretical analysis of electroencephalography-derived minimum spanning tree in 5- and 7-year-old children reflects brain maturation. Brain Connect. 2013:50–60. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma M, Smit DJ, de Bie HM, van Baal GCM, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC, et al. Network analysis of resting state EEG in the developing young brain: structure comes with maturation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:413–425. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, Barr DJ, Garrod S, Kessler K. Conversational interaction in the scanner: mentalizing during language processing as revealed by MEG. Cerebral Cortex. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer J, Anwander A, Friederici AD. Neuroanatomical prerequisites for language functions in the maturing brain. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:459–466. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. A first language: The early stages. London: George Allen & Unwin Publishing; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Broser PJ, Groeschel S, Hauser TK, Kidzba K, Wilke M. Functional MRI-guided tractography of cortico-cortical and cortico-subcortical language networks in children. Neuroimage. 2012;63(3):1561–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks; graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Neurosci. 2009;10:186–198. doi: 10.1038/nrn2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, Edwards E, Dalal SS, Soltani M, Nagarajan SS, Kirsch HE, Berger MS, Barbaro NM, Knight RT. High gamma power is phase-locked to theta oscillations in human neocortex. Science. 2006;313:1626–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1128115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, Knight RT. The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne D, Bakhtazad L, Gaetz W. Spatiotemporal mapping of cortical activity accompanying voluntary movements using an event-related beamforming approach. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:213–229. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne D, Bostan AC, Gaetz W, Pang EW. Event-related beamforming: a robust method for presurgical functional mapping using MEG. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1691–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikoeitz M. Age and sex effect: development of the normal child. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:806–814. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cycowicz YM, Friedman D, Rothstein M, Snodgrass JG. Picture naming by young children: norms for name agreement, familiarity and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1997;65:171–237. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1996.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaconescu AO, Alain C, McIntosh AR. The co-occurance of multisensory facilitation and cross-modal conflict in the human brain. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:2896–2909. doi: 10.1152/jn.00303.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick AS, Tremblay P. Beyond the arcuate fasciculus: consensus and controversy in the connectional anatomy of language. Brain. 2012;135(12):3529–3550. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doesburg SM, Vinette SA, Cheung MJ, Pang EW. Theta-modulated gamma-band synchronization among activated regions during a verb generation task. Front Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doesburg SM, Emberson LL, Rahi A, Cameron D, Ward LM. Asynchrony from synchrony: long-range gamma-band neural synchrony accompanies perception of audiovisual speech asynchrony. Exp Brain Res. 2008;185:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doesburg SM, Vidal J, Taylor MJ. Reduced theta connectivity during set-shifting in children with autism. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013a;7:785. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doesburg SM, Moiseev A, Herdman AT, Ribary U, Grunau RE. Region-specific slowing of alpha oscillations is associated with visual-perceptual abilities in children born very preterm. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013b;7:791. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner TH, Siegel M. A framework for local cortical oscillation patterns. Trends Cogn Neurosci. 2011;15:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 3. Circle Pines: MN: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ewald A, Aristei S, Nolte G, Rahman RA. Brain oscillations and functional connectivity during overt language production. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:e166. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD. The brain basis of language processing: from structure to function. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91(4):1357–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD. The neural basis of language development and its impairment. Neuron. 2006;52(6):941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HM, Lee ES, Yeatman JD, Yeom KW. Language and reading skills in school-aged children and adolescents born preterm are associated with white matter properties on diffusion tensor imaging. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(14):3348–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard WD, Hertz-Pannier L, Mott SH, Barnett AS, Le Bihan D, Theodore WH. Functional anatomy of cognitive development: fMRI of verbal fluency in children and adults. Neurology. 2000;54(1):180–185. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N. The organization of language in the brain. Science. 1970;170:940–944. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3961.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud AL, Poeppel D. Cortical oscillations and speech processing: emerging computational principles and operations. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(4):511–517. doi: 10.1038/nn.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golfinopoulos E, Tourville JA, Guenther FH. The integration of large-scale neural net- work modeling and functional brain imaging in speech motor control. Neuroimage. 2010;52:862–874. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou Z, Choudhury N, Benasich AA. Resting frontal gamma power at 16, 24 and 36 months predicts individual differences in language and cognition at 4 and 5 years. Behav Brain Res. 2011;220:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther FH, Ghosh SS, Tourville JA. Neural modelling and imaging of the cortical interactions underlying syllable production. Brain and Language. 2006;96(3):280–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell HE. The challenge of adolescence. Topics in Language Disorders. 1984;4(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Wang L, Chen ZJ, Yan C, Yang H, et al. Uncovering intrinsic modular organization of spontaneous brain activity in humans. PLoS One. 2009;5:e15238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman AT. Functional communication within a perceptual network processing letters and pseudoletters. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;28(5):441–449. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e318230da5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes D, Miller KJ, Vansteensel MJ, Edwards E, Ferrier CH, Bleichner MG, van Rijen PC, Aarnoutse EJ, Ramsay NF. Cortical theta wanes for language. NeuroImage. 2014;85:738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Pannier L, Gaillard WD, Ott SH, Cuenod CA, Bookheimer SY, Weinstein S, Conry J, Papero PH, Schiff SJ, Le Bihan D, Theodore WH. Noninvasive assessment of language dominance in children and adolescents with functional MRI: a preliminary study. Neurology. 1997;48(4):1003–1012. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92:67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland SK, Vannest J, Mecoli M, Jacola LM, Tillema JM, Karunanayaka PR, Schmithorst VJ, Yuan W, Plante E, Byars AW. Functional MRI of language lateralization during development in children. International Journal of Audiology. 2007;46:533–551. doi: 10.1080/14992020701448994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indefrey P, Levelt WJ. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition. 2004;92:101–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2002.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadis DS, Pang EW, Mills T, Taylor MJ, McAndrews MP, Smith ML. Characterizing the normal developmental trajectory of expressive language lateralization using magnetoencephalography. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:896–904. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi M, Yoshimura Y, Shitamichi K, Ueno S, Hirosawa T, Munesue T, Ono Y, Tsubokawa T, Haruta Y, Oi M, Niida Y, Remijin GB, Takahashi T, Suzuki M, Higashida H, Minabe Y. A custom magnetoencephalography device reveals brain connectivity and high reading/decoding ability in children with autism. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1139. doi: 10.1038/srep01139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi M, Shitamichi K, Yoshimura Y, Ueno S, Remijin GB, Hirosawa T, Munesue T, Tsubokawa T, Haruta Y, Oi M, Minabe Y. Lateralized theta wave connectivity and language performance in 2- to 5-year-old children. J Neurosci. 2011;31(42):14984–14988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2785-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalancette M, Quraan M, Cheyne D. Evaluation of multiple-sphere head models for MEG source localization. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56(17):5621–5635. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/17/010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer N, Pedroni A, Gianotti LRR, Hänggi J, Knoch D, Jäncke L. Functional brain network efficiency predicts intelligence. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:1393–1403. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AC, Ye AX, Wong SM, Taylor MJ, Doesburg SM. Reduced beta band connectivity during emotional face processing in adolescent with autism. Molecular Autism. 2014;5:51. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Qiu C, Gentili C, Walter M, Pan Z, Ding J, et al. Altered effective connectivity network of the amygdala in social anxiety disorder: A resting-state fMRI study. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Jensen O. The theta-gamma neural code. Neuron. 2013;77(6):1002–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AR. Towards a network theory of cognition. Neural Netw. 2000;13:861–870. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(00)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellem MS, Friedman RB, Medvedev AV. Gamma- and theta-band synchronization during semantic priming reflect local and long-range lexical-semantic networks. Brain and Language. 2013;127:440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchia G, Choudhury NA, Ortiz-Mantilla S, Realpe-Bonilla T, Roesler CP, Benasich AA. Oscillatory support for rapid frequency change processing in infants. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:2812–2824. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onnela JP, Saramaki J, Kertesz J, Kaski K. Intensity and coherence of motifs in weighted complex networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;71(6,2):065103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.065103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piai V, Roelofs A, Maris E. Oscillatory brain responses in spoken word production reflect lexical frequency and sentential constraint. Neuropsychologia. 2014;53:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palva JM, Monto S, Kulashekhar S, Palva S. Neuronal synchrony reveals working memory networks and predicts individual memory capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7580–7585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913113107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palva S, Palva JM. New vistas for alpha-frequency band oscillations. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(4):150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palva S, Palva JM. Discovering oscillatory interaction networks with M/EEG: challenges and breakthroughs. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang EW, Wang F, Malone M, Kadis DS, Donner EJ. Localization of Broca’s area using verb generation tasks in the MEG: validation against fMRI. Neurosci Lett. 2011;490:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ. The anatomy of language: a review of 100 fMRI studies published in 2009. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1191:62–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ. A review and synthesis of the first 20 years of PET and fMRI studies of heard speech, spoken language and reading. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):816–847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Deus J, Losilla JM, Capdevila A. Cerebral lateralization of language in normal left-handed people studied by functional MRI. Neurology. 1999;52(5):1038–1043. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Soriano-Mas C, Ortiz H, Sebastian-Galles N, Losilla JM, Deus J. Myelination of language-related areas in the developing brain. Neurology. 2006;66(3):339–343. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201049.66073.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden S, Richardson FM, Josse G, Thomas MS, Ellis C, Shakeshaft C, Seghier ML, Price CJ. Verbal and non-verbal intelligence changes in the teenage brain. Nature. 2011;479(7371):113–116. doi: 10.1038/nature10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redcay E, Haist F, Courchesne E. Functional neuroimaging of speech perception during a pivotal period of language acquisition. Developmental Science. 2008;11:237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressel V, Wilke M, Lidzba K, Lutzenberger W, Krägeloh-Mann I. Increases in language lateralization in normal children as observed using magnetoencephalography. Brain Lang. 2008;106(3):167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. NeuroImage. 2010;52:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Donner TH, Engel AKL. Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:121–134. doi: 10.1038/nrn3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SK. The neurobiology of speech perception and production – Can functional imaging tell us anything we did not already know? Journal of Communication Disorders. 2012;45:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoffelen J-M, Gross J. Source connectivity analysis with MEG and EEG. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:1857–1865. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Vanderwart M. A standardized set of 260 pictures: norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1980;12(1):147–154. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.6.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam CJ, Nolte GN, Daffertshofer A. Phase lag index: assessment of functional connectivity from multichannel EEG and MEG with diminished bias from common sources. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28:1178–1193. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekar K, Menon V, Rubin D, Musen M, Greicius MD. Network analysis of intrinsic functional brain connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Comp Biol. 2008;4:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Altaye M, Rajagopal A, Eaton K, Meng X, Plante E, Holland SK. A 10-year longitudinal fMRI study of narrative comprehension in children and adolescents. Neuroimage. 2012;63(3):1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Schmithorst VJ, Altaye M, Byars AW, Ret J, Plante E, Holland SK. A longitudinal functional magnetic resonance imaging study of language development in children 5 to 11 years old. Annals of Neurology. 2006;59:796–807. doi: 10.1002/ana.20817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher RW, North DM, Biver CJ. Intelligence and EEG phase reset: A two compartmental model of phase shift and lock. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1639–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Pipa G, Lima B, Melloni L, Neuenschwander S, Nicolic D, Singer W. Neural synchrony in cortical networks:history, concept and current status. Front Integr Neurosci. 2009a;3:17. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.017.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Roux F, Singer W, Haenschel C, Siretenu R, Rodriguez E. The development of neural synchrony reflects late maturation and restructuring of functional networks in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009b;106:9866–9871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Roux F, Rotarska-Jagiela A, Singer W. Neural synchrony and the development of cortical networks. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pelt S, Boomsa DI, Fries P. Magnetoencephalography in twins reveals a strong genetic determination of the peak frequency of visually induced gamma-band synchronization. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(10):3388–3392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5592-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannest V, Karunanayaka PR, Schmithorst VJ, Szaflarski JP, Holland SK. Language networks in children: evidence from functional MRI studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(5):1190–1196. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela F, Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J. The brain-web: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:229–239. doi: 10.1038/35067550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Stein A, Sarnthein J. Different frequencies for different scales of cortical integration: from local gamma to long-range alpha/theta synchronization. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;38:301–313. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhu C, He Y, Zhang Y, Cao Q, Zhang H, et al. Altered small-world functional network in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:638–649. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S, Mueller HM. ‘Too many betas do not spoil the broth’: The role of beta brain oscillations in language processing. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:201. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, Naglieri JA. Wechsler nonverbal scale of ability. Pearson; San Antonio: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KT. Expressive Vocabulary Test. Circle Pines: MN: American Guidance Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Xia M, Wang J, He Y. BrainNet Viewer: a network visualization tool for human brain connectomics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Huang D, Singer W, Nikolic D. A small world of neuronal synchrony. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(12):2891–2901. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuval-Greenberg S, Tomer O, Kerenm AS, Nelken AS, Deouell LY. Transient induced gamma-band response in EEG as a manifestation of miniature saccades. Neuron. 2008;58(3):429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalesky A, Cocci L, Fortino A, Murray MM, Bullmore E. Connectivity differences in brain networks. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalesky A, Fortino A, Bullmore E. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. Neuroimage. 2010;53:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]