Abstract

It is well supported by behavioral and neuroimaging studies that typical language function is lateralized to the left hemisphere in the adult brain and this laterality is less well defined in children. The behavioral literature suggests there maybe be sex differences in language development but this has not been examined systematically using neuroimaging. In this study, magnetoencephalography (MEG) was used to investigate the spatiotemporal patterns of language lateralization as a function of age and sex. Eighty typically developing children (46 females; 4–18 years) participated in an overt visual verb generation task. An analysis method called differential beamforming was used to analyse language-related changes in oscillatory activity referred to as low-gamma event-related desynchrony (ERD). The proportion of ERD over language areas relative to total ERD was calculated. We found different patterns of laterality between boys and girls. Boys showed left hemisphere lateralization in the frontal and temporal language-related areas across age groups, whereas girls showed a more bilateral pattern, particularly in frontal, language related, areas. Differences in patterns of ERD were most striking between boys and girls in the younger age groups and these patterns became more similar with increasing age, specifically in the pre-teen years. Our findings show sex differences in language lateralization during childhood; however, these differences do not seem to persist into adulthood. We present possible explanations for these differences. We also discuss the implications of these findings for pre-surgical language mapping in children and highlight the importance of examining the question of sex-related language differences across development.

Keywords: magnetoencephalography (MEG), verb generation, inferior frontal gyrus, event-related desynchronization, gamma oscillations

Introduction

In a typical right-handed adult, it is well accepted that language dominance is lateralized to the left hemisphere of the brain, and that this lateralization emerges between early childhood and adolescence. Behavioral studies have suggested that boys and girls develop language differently. This is most evident in early childhood (Bornstein et al., 2000; Dionne et al., 2003) and continues through to adolescence, where girls reportedly show slightly better expressive language skills than boys.

Clinical neuroimaging studies, first completed with patients with epilepsy and brain lesions prior to surgery (Bowyer et a., 2004; Bowyer et al., 2005; Pirmoradi et al., 2010), determined that verb generation tasks had the highest accuracy for localizing frontal language areas. This accuracy was confirmed in studies directly comparing fMRI and MEG (Kamada et al., 2007; Pang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). It was confirmed that, using the verb generation task, control adults demonstrated a left hemisphere dominance for language (Fisher et al., 2008; Ressel et al., 2006) and both functional MRI (fMRI: Brown et al., 2005; Holland et al., 2001; Szaflarski et al., 2006) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies (Kadis et al., 2011; Ressel et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012) concur that this laterality emerges from early childhood to adolescence. While these neuroimaging studies have consistently reported language lateralization increases as a function of age during childhood, there is no clear confirmation of the behavioral findings of sex differences in language development.

In adults, fMRI studies of sex-related language laterality are equivocal. Some have reported different patterns of brain activation during language processing with a greater degree of lateralization in adult males and more bilateral activation in adult females (Baxter et al., 2003; Clements et al., 2006; Jaeger et al., 1998; Kansaku & Kitazawa, 2001; Kitazawa & Kansaku, 2005; Shaywitz et al., 1995; Weiss et al., 2003). However, other fMRI studies in adults have not found sex differences in language lateralization (Allendorfer et al., 2011; Buckner et al., 1995; Frost et al., 1999; Gur et al., 2000; Hirnstein et al., 2012). These discrepant findings could be attributed to the use of different language tasks, varying sample sizes in the studies, and/or different approaches utilized in data analysis (Allendorfer et al., 2011; Gaillard, et al., 2003a; Harrington & Farias, 2008; Hirnstein et al., 2012).

Although there have been quite a few neuroimaging studies investigating language lateralization in children, to date, there are four imaging studies which specifically address the issue of sex-related differences in language lateralization in the developmental domain. Three of these studies used fMRI (Burman et al., 2008; Gaillard et al., 2003b; Plante et al., 2006) and one used event-related potentials (ERP; Spironelli et al., 2010). The two earlier fMRI studies (Gaillard et al., 2003b; Plante et al., 2006) did not find main effects of sex and suggested that sex differences may be age- and task-dependent (Plante et al., 2006). In the latter study, (Plante et al., 2006), fMRI was recorded from 205 children aged 5 to 18 years while they performed four different language tasks. Although no significant sex differences (main effect) were found for laterality across all language tasks, they found a strong interaction of sex and age, particularly, on the auditory verb generation task. Instead of a simple level-of-activation difference, they observed different slopes for the age effect between boys and girls. They suggest that these sex effects may be due to a differential allocation of physiological resources to the task by boys and girls, depending on the task and depending on their age.

The third fMRI study, however, found a significant sex difference in language lateralization in children (Burman et al., 2008), as did an ERP study (Spironell et al., 2010). Burman and colleagues (2008) tested 62 children aged 9–15 years as they performed spelling and rhyming language tasks in both the visual and auditory modalities.. They observed that activations in frontal and temporal regions were bilaterally stronger in girls, whereas boys always exhibited unilateral left activations in all regions. The authors suggested that the activation patterns may reflect different approaches to linguistic processing, where girls rely on a supramodal (modality in-specific) language network and boys relied on modality-specific network. In the ERP study, Spironelli and colleges (2010) recorded data from 28 ten-year-old children as they performed three language (phonological, semantic, and orthographic) tasks. Consistent with Burman et al.’s finding (2008), they demonstrated left lateralization for boys over anterior sites during the phonological task whereas girls exhibited bilateral activation in all tasks.

In recent years, MEG has increasingly been used to investigate the localization (Kadis et al., 2008), lateralization (Kadis et al., 2011; Ressel et al., 2008), and performance (Kikuchi et al., 2011) on language tasks in children. In young children, the MEG may be a preferable imaging modality as it offers a less restrictive and less noisy testing environment compared to the fMRI (Pang, 2011). As well, MEG offers better temporal resolution and can be used to examine both evoked (time-locked) and induced (task-related oscillatory-changes) responses in the brain. Studies have reported that gamma band cortical oscillatory activity is associated with higher-order cognitive processes such as lexical processing (Eulitz et al., 1996; Ihara et al., 2003; Pulvermuller et al., 1996; Pulvermuller et al., 1995), attention (e.g., Tiitinen et al., 1993), and reading (e.g., Hirata et al., 2002). While there have been few studies on the developmental trajectory of gamma oscillations, an EEG study found task-specific gamma changes with age (Yordanova et al., 2002) and an MEG study found significant reduction of movement-related gamma in children and even adolescents (Gaetz et al., 2010). Kadis et al. (2008; 2011) used changes in high beta / low gamma desynchronization to localize frontal language areas in a group of children. Given the lack of evidence for sex-related developmental differences in language task-related oscillatory changes, there is a need to systematically examine this question.

Of the four imaging studies which specifically addressed the question of sex-related differences in language lateralization in children, the study by Plante et al. (2006), described above, suggested that verb generation may be most promising when looking for sex-related developmental changes in language processing. The verb generation task, which involves word retrieval, semantic and expressive language processing, has been widely used in many imaging studies underlying language processing (e.g., Baciu et al., 1999; Gaillard et al., 2003; Pujol et al., 1999). Across studies, the verb generation task has consistently been found to activate the inferior frontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, superior temporal and middle temporal gyri. To gain insight into the maturation of the lateralization of the language neural network, we tested boys and girls, children and adolescents, on a visual verb generation task in the MEG, to determine whether there are cortical oscillatory changes in brain regions known to be involved in language processing. Our specific aim was to investigate the sex-related differences in language lateralization in children using magnetoencephalography (MEG).

Methods

Participants

Eighty typically developing children and adolescents (46 girls, 34 boys), aged 4 to 18 years, were grouped into five age groups (see Table 1 for full description). All participants were right-handed native English speakers. Only right-handed participants were recruited to avoid the potential confounds from different developmental trajectories for language lateralization in left-handed and ambidextrous participants (Knecht et al., 2000; 2003; Pujol et al., 1999; Szaflarski et al., 2002; 2006; 2012).

Table 1.

Numbers of participants by sex and age group (N = 80; 46 girls, 34 boys)

| Group | 4 ~ 6 yrs | 7 ~ 9 yrs | 10 ~ 12 yrs | 13 ~ 15 yrs | 16 ~ 18 yrs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girl | 5 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 |

| Boy | 5 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 7 |

Handedness was strongly right-handed with an average score of 75.2 ± 16.2 SD (girls: 73.7 ± 15.7 SD; boys: 76.7 ± 16.7 SD) as measured by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971). Parents of the child participants, and adolescents themselves, completed screening questionnaires to ascertain that there were no known or suspected histories of speech, language, hearing or developmental disorders. Before the experiment, children received two standardized neuropsychological tests: the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (3rd Ed.) (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 1997) and the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT; Williams, 1997). Table 2 summarizes the mean scores and standard deviations for each test by each age group. Results confirmed that all children’s scores were at or above expected scores for their ages. These tests were administered to ensure that all children participants were ‘typically developing’ with regards to language and could be included in our cohort. All parents gave informed consent; children and adolescents provided assent and consent, as age appropriate. This study was approved by our Research Ethics Board.

Table 2.

Standardized scores of each language test by age group and sex. There were no significant differences among groups.

| Age Group | 4 ~ 6 | 7 ~ 9 | 10 ~ 12 | 13 ~ 15 | 16 ~18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls standardized scores and standard deviation (in parentheses) | |||||

| PPVT | 115.3 (9.9) | 116.8 (8.0) | 115.6 (9.1) | 116.1 (8.8) | 117.2 (8.7) |

| EVT | 112.8 (12.5) | 113.5 (2.4) | 110.2 (4.1) | 113.6 (10.0) | 111.7 (10.5) |

| Boys standardized scores and standard deviation | |||||

| PPVT | 114.9 (9.5) | 115.7 (6.2) | 113.0 (4.2) | 116.3 (7.2) | 116.2 (8.0) |

| EVT | 112.6 (10.9) | 109.0 (4.8) | 114.0 (4.5) | 112.8 (10.6) | 109.6 (8.1) |

Verb generation paradigm description and procedure

The verb generation task was based on that described by Kadis et al. (2011). The paradigm contained pictures of 80 objects where the names and usages are familiar to typically developing children as young as five years of age. The stimuli subtended 5 degrees of arc and were back-projected in the MEG to a screen fixed at a distance of appropriately 65 cm from the participants’ eyes. Stimuli were presented using Presentation software (Neurobehavioral System, Albany, CA).

During the task, children were asked to overtly generate one “action word” associated with the picture stimulus as quick as possible. For example, if the picture stimulus was a “ball”, participants might verbally produce a verb, for example, “kick”, or “hit”. Stimuli were presented for 500 ms in random order without repetition with a stimulus offset asynchrony of 1500–2500 ms. Between stimuli, participants were instructed to focus on a fixation image (small white cross) to minimize eye movements. Prior to MEG scanning, participants were trained using a separate set of comparable stimuli. Subjects, especially the young children, were instructed and reminded to stay ‘as still as statues’ while they completed the test. Head localizations were performed before and after data acquisition and runs with head movements >5 mm were repeated. Verbal responses were monitored in the MEG by the research assistant and checked for compliance and appropriateness. If there were any concerns about performance, the task was stopped, clearer instructions or additional practice were given, and the task re-started. All children completed the task with close to 100% performance. The task required about six minutes of MEG scanning time.

MEG and structural MRI data acquisition

Prior to entering the MEG, fiducial markers were placed on each subject’s nasion and both pre-auricular points. Participants were tested in the supine position in a magnetically shielded room in the Neuromagnetic Lab at the Hospital for Sick Children. A CTF 151-channel whole-head MEG system (MISL, Coquitlam BC) was used. MEG signals were digitized at a sampling rate of 625 Hz with a 200 Hz low-pass filter. After completion of the MEG, the fiducial markers were replaced by contrast markers visible on MRI. A structural MRI was obtained for each subject (T1-weighted MPRAGE) on a 3T scanner (Siemens Trio, Aktiengesellschaft, Munich).

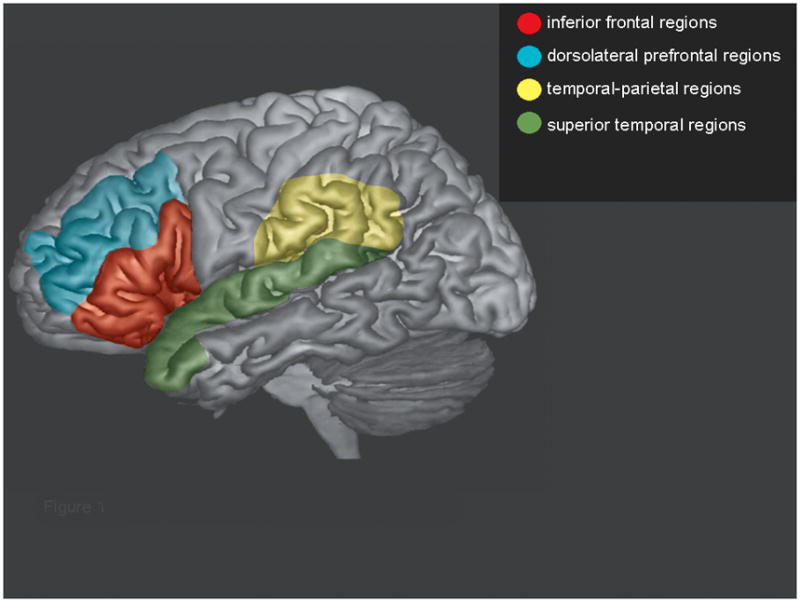

Selection of language areas: Extensive frontal and temporal lobe regions of interest

Based on the fMRI and MEG literature using the verb generation task, we selected regions of interest (ROIs; Figure 1) which included areas in the frontal lobe (Brodmann Areas 44, 45, 47), the adjoining dorsolateral prefrontal areas (BA 9, 46), areas in the temporal-parietal lobe (BA 39, 40), adjacent areas in the superior temporal lobes (BA 22, 38, 41, 42), inferior-and middle temporal regions (BA 21), and the homologues of these regions in the right hemisphere.

Figure 1.

Left hemisphere regions of interest used in the data analyses. The right hemisphere homologues of these regions were also used.

Data analysis

Differential beamformer analysis

Data were pre-processed using CTF software. Continuous MEG data were epoched into trials which were scanned to identify artefacts related to movement and eye blinks. Epoched data were uploaded and analysed using BrainWave v.1.5 (http://cheynelab.utoronto.ca/). Differential beamformer analyses (Robinson & Vrba, 1999; Vrba & Robinson, 2001) were used to investigate the brain activity during the verb generation task for each participant. This approach involved direct comparisons of changes in oscillatory activity, in selected frequency ranges, in active periods versus a baseline. Previous MEG studies have determined that language and cognitive processing correspond primarily to low-gamma band activity (Galambos et al., 1981; Hirata et al., 2002; Ihara et al., 2003; Lutzenberger et al., 1994; Muller et al., 1996; Pulvermuller et al., 1996; Tiitinen et al., 1993). Thus, in each participant, low-gamma (25–50Hz) event-related desynchrony (ERD) and synchrony (ERS) were analyzed. Other studies (Kadis et al., 2011; Ressel et al., 2008) have implicated low-beta band (13–23 Hz) involvement in language processing; thus, we also analysed ERD and ERS in the 13–23 Hz range.

Time windows (TW) were set at 150 ms widths. The baseline was defined as −200 to −50 ms pre-stimulus and six active windows were set as the following: 50–200 ms (TW 150 ms), 150–300 ms (TW 250 ms), 250–400 ms (TW 350 ms), 350–500 ms (TW 450 ms), 450–600 ms (TW 550 ms), and 550–700 ms (TW 650ms). The analysis was set to include the whole brain with a 5 mm voxel resolution. Beamformer images were overlaid onto each subject’s MRI and warped into standard space with Talaraich coordinates. The BrainWave v.1.5 package uses the Talaraich coordinates to identify neuroanatomical locations and Brodmann area labels.

Quantification of the extent of ERD/ERS activity in language areas

We calculated the extent of ERD/ERS activity, weighted by magnitude, in language areas (as identified in Table 3) as a function of total ERD/ERS over the whole brain for each subject. These values were grouped by age and sex and submitted to two statistical analyses: the first analysis was a linear regression model with continuous (age) and categorical (sex) predictors, and the percentage of ERD/ERS as the dependent variable. Regression analysis allowed us to determine whether there were significant interaction effects of sex and age on the patterns of distribution of ERD/ERS during the verb generation task. We further conducted separate analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) for each age group, with sex as the independent variable, time windows as the covariate, percentage of ERD/ERS in language areas as a function of whole-brain ERD/ERS as the dependent variable, and applied a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 3.

Brodmann areas showing ERD during the verb generation task by age, sex and time window (ms). Italics indicate temporal lobe areas (BA 22, 39, 38, 40, 41, 42). Bold indicates lateral and inferior frontal areas (BA 9, 44, 45, 46, 47).

| TW | 4–6F | 7–9F | 10–12F | 13–15F | 16–18F | 4–6M | 7–9M | 10–12M | 13–15M | 16–18M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left hemisphere | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 150 ms | BA39 | BA45 | BA44 | BA22, 44 | BA 38 | BA38 | BA9 | BA45 | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| 250ms | BA37 | BA45 | BA47 | BA9 | BA22, 44 | BA38 | BA38 | BA9 | BA40, 45 | |

|

|

||||||||||

| 350 ms | BA38 | BA45 | BA47 | BA9 | BA44, 46, 47 | BA38, 45 | BA22, 47 | BA9 | BA45 | |

|

|

||||||||||

| 450 ms | BA38 | BA45 | BA46 | BA47 | BA44, 47 | BA38, 47 | BA47 | BA47 | BA45 | |

|

|

||||||||||

| 550 ms | BA38 | BA45 | BA9, 38 | BA44 | BA47 | BA47 | BA39 | BA45, 46 | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| 650 ms | BA44 | BA38 | BA45 | BA47 | BA9 | BA44, 47 | BA47 | BA38 | BA45 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Right hemisphere | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 150 ms | BA39, 9 | BA9 | BA38, 45 | BA9 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 250 ms | BA9 | BA40 | BA45 | BA45 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 350 ms | BA41 | BA9 | BA46 | BA45 | BA47 | BA46 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 450 ms | BA41, 46 | BA9 | BA9 | BA45 | BA22 | |||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 550 ms | BA42, 45 | BA46 | BA47 | BA45 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 650 ms | BA42 | BA22 | BA45, 47 | BA46 | BA9 | BA47 | ||||

F = girls; M = boys; BA = Brodmann Area

Results

Behavioral results

Table 2 summarizes the mean standard scores and standard deviations for the PPVT and EVT assessments. In order to screen for possible sex and/or age effects in the participants’ language competence and verbal skills, as ascertained by neuropsychological assessments, we computed two-way ANOVAs with the factors age and sex. The results showed no significant main effects for age (PPVT: F (1,79) = .827, p = .524; EVT: F (1, 79) = 1.100, p = .362) or sex (PPVT: F (1, 79) = 2.112, p = .100; EVT: F (1, 79) = .590, p = .671) and no interaction effect (PPVT: F (1, 79) = .609, p = .685; EVT: F (1, 79) = .161, p = .957). This was repeated with the PPVT and EVT raw scores and again the results confirm no differences in language competence and verbal skills between boys and girls (PPVT: F (1, 79) = 2.193, p =.142; EVT: F (1, 79) = .590, p = .671).

Sex differences in spatiotemporal patterns of language lateralization

The results from the beamformer analyses revealed consistent patterns of gamma ERD activity in the frontal and temporal regions across six time windows. Analysis of the gamma ERS activity and beta ERS and ERD failed to show any pattern of significant activity. We observed that low-gamma (25–50 Hz) ERD associated with language processing started to emerge in the first time window and remained into the 550–700 ms window for all age groups as shown in Table 3. ERD was found in both the frontal and temporal ROIs for girls and boys across all age groups during the verb generation task (Table 3); however, girls and boys showed different activation patterns. Boys showed lateralization of ERD to the left hemisphere both in the frontal and temporal ROIs across age groups. In contrast, ERD was found to have a more bilateral distribution, particularly in the frontal ROIs for the girls. These different patterns of language lateralization were particularly striking in the young children (i.e., Groups 4–6, 7–9, 10–12, 13–15), where Group 4–6 showed a strong right lateralized pattern for girls. More left-lateralized ERD, similar to the boys, was found for girls in the 16–18 year old group.

Sex differences in the pattern of ERD over language areas

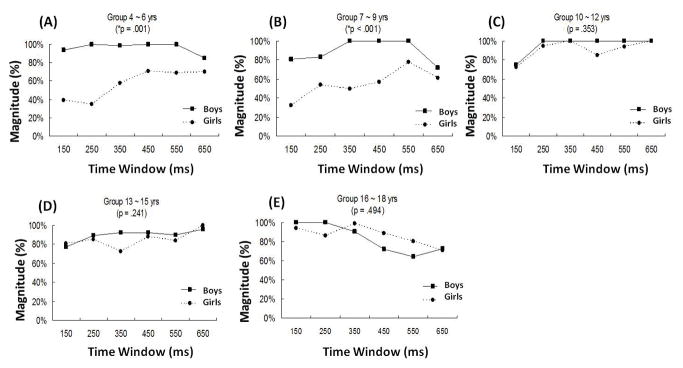

We observed differences, between boys and girls, in the magnitude of ERD in the frontal and temporal ROIs as a function of whole-brain ERD. Regression analysis showed a significant interaction effect of sex and age (t (78) = 5.309, p < .001) on the magnitude of ERD in the ROI. We then conducted separate ANCOVAs examining the effect of sex for the five separate age groups, and applied a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. This further revealed significant sex differences on the patterns of ERD over time windows for the two youngest age groups: 4–6 years (F (1, 79) = 20.908, p = .001) and 7–9 years (F (1, 79) = 36.820, p < .001). No sex differences were found for the rest of the age groups (10–12 years: F (1, 79) = 0.959, p = .353; 13–15 years: F (1, 79) = 1.575, p = .241; 16–18 years: F (1. 79) = .507, p = .494). Figure 2 illustrates these patterns. Boys, for all age groups, across the entire task window, exhibited the majority of their ERD in left hemisphere language-related areas. In contrast, girls, especially in the younger age groups, showed a different pattern of task-related localization of ERD. Compared to boys, girls showed a lower and more varied proportion of ERD in left hemisphere language areas compared to ERD over the whole brain for groups 4–6 and 7–9 years (Figure 2a and b); however, a pattern similar to the boys, with a greater proportion of ERD in language areas, was observed in groups 10–12, 13–15 and 16–18 years (Figure 2c to e).

Figure 2.

Patterns of ERD over time windows for each age group (a to e) for boys (squares) and girls (circles). The x-axis shows the time windows and the y-axis shows percent of ERD in language areas relative to ERD over the whole brain. Table 3 contains the Brodmann areas that were used to compute the data in this figure.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate the sex differences in spatiotemporal patterns of language lateralization in children across development. To our knowledge, this is the first MEG evidence of language-related sex differences in childhood, although this is a well-accepted phenomenon in the behavioral literature. In our data, gamma band event-related desynchrony (ERD) was found consistently within language-related areas during the verb generation task for all participants. Our data concur with other MEG studies where low-gamma ERD activity was observed to reflect language processing (Hirata et al., 2002; 2004; Ihara et al., 2003). In fact, Hirata et al. (2002) concluded that low gamma-band (25–50 Hz) activity is related to both syntactic and semantic aspects of language processing (Hirata et al., 2004). ERS was not consistently seen in this cohort. It should be noted that we did not find beta ERS or ERD which has been reported in other studies of expressive language localization in children (Kadis et al., 2011; Ressel et al., 2008). This may be due to our intentional exclusion of motor and pre-motor areas (BA4 and BA6) from our analyses whereas both Kadis et al. and Ressel et al. included the whole frontal lobe, defined as the area anterior to the central sulcus. Motor control is known to be in the beta band (Pfurtscheller & Lopes da Silva, 1999), thus by excluding these areas, we were able to dissociate the language from the motor control aspects of verb generation.

Consistent with examples in the literature (Baciu et al., 1999; Gaillard et al., 2003; Kunii et al., 2013; Pujol et al., 1999), our data demonstrated that inferior frontal and superior temporal gyri, along with other language associated regions, were active during a verb generation task, although the level of activity in these regions varied depending on the age and sex of the participant. Whereas boys showed a stronger left lateralized activation in the frontal and temporal areas during the verb generation task, girls failed to show this typical lateralized pattern and exhibited a more bilateral activation, particularly with extensively bilateral distribution in the frontal regions (Table 3). This is in alignment with the findings of Burman et al. (2008) and Spironelli et al. (2010). Our results suggest that measurement of changes in gamma ERD activity track the development of different aspects of the language network in boys and girls.

Our data further demonstrated that left hemisphere language lateralization emerged in early childhood for the boys and remained lateralized throughout adolescence, whereas girls exhibited a more bilaterally activated language network at a younger age, with more left lateralization appearing around the age of 16 years. Typically, a left lateralized language network is associated with more mature language function, thus, at first glance, it appears that the mature pattern of language lateralization arises earlier in boys than in girls, and girls do not acquire this typical left-lateralized pattern until after puberty. This is in contrast to the developmental literature which suggests that girls have slightly better expressive language skills than boys, and to our neuropsychological assessments which did not find any differences in language ability between boys and girls. While our participants were typically developing control volunteers recruited from the community, their PPVT and EVT scores were in the high range of normal, and this should be taken into consideration when interpreting these results. However, taking together the participants’ behavioral performance and their lateralization patterns, it is unlikely that the lateralization pattern seen in our study reflects sex differences in language development or performance, but may instead reflect differences in brain functional neurophysiology between boys and girls.

Another interesting finding in the present study is the different patterns seen in ERD magnitude in the language related regions between boys and girls. While performing the verb generation task, boys demonstrated more focal clusters of higher magnitude ERD within language-related areas from an early age through to adolescence; in contrast, girls exhibited less focal and lower magnitude ERD over language areas at an early age; this changed around the age of 10 years and became more similar to what was seen in the boys. Again, given the absence of differences on performance of the task and on neuropsychological assessment, these different patterns cannot be attributed to differences in language development but could reflect functional differences in activation of the language network between boys and girls.

While it is not clear is why the lateralization of growth patterns between boys and girls in the language-related areas converge at around 10 years of age. The suggestion of differences in the functional neurophysiology of the brain between boys and girls is supported by evidence of neuroanatomical changes related to sex and age. Males show more prominent age-related gray and white matter volume changes during brain development (De Bellis et al., 2001; Lenroot et al., 2007; Lenroot & Giedd, 2010; Perrin et al., 2009) whereas females show greater and earlier changes in the corpus callosum (De Bellis et al., 2001; Lenroot & Giedd, 2010). This could explain the asymmetry of brain processing seen in our language task where boys demonstrate left hemisphere dominance across development while girls show bilateral activation as the changes in their corpus callosum would facilitate interhemispheric communication. Indeed, Sakai (2005) suggested that developmental callosal changes during early childhood shapes language processing in the brain network and is integral to cortical maturation and learning to speak, read or write. However, in our data, it is not clear why the shift from bilateral to left lateralization occurred later in girls, and, in the boys, it is not clear why lateralization did not become bilateral with the development of callosal pathways. One possible explanation is that the left hemisphere is necessary for efficient language processing. As the boys already show left lateralization at a younger age, the development of the callosal pathway does not affect this laterality and does not cause a shift into the right hemisphere. For the girls, however, as they show bilateral activation at a younger age, the development of the callosal pathway allows them to shift more into the left hemisphere to take advantage of the more efficient language processing system. This explanation is entirely speculative and requires further testing and validation.

An alternative explanation for the different ERD patterns observed in our study is that boys and girls may utilize different strategies during the verb generation task. There is evidence from behavioral studies for sex-related differences in language processing strategies, where males recall words in the order of presentation (Kimura, 1999; Kramer et al., 1988), while females employ categorical organization to recall words in memory tasks (Cox & Waters, 1986; Kimura, 1999; Kramer et al., 1997; 1988). Several fMRI studies have reported that the recruitment of right frontal cortex was associated with the categorization process in semantic memory (Grossman et al., 2002b; Olga et al., 2008). As well, significantly reduced activation in this area for multiple categories of knowledge was observed in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Grossman et al., 2002a). In line with these findings, our results suggest that girls may use the typical left-lateralized language network, but draw on regions in the right hemisphere as part of their strategy for language processing. This would result in a more bilaterally active system for girls and a more typical, language-specific system, for boys.

Our study design tracked subject accuracy and compliance on-line. As subjects performed the verb generation task, their responses were checked by a research assistant for accurate, appropriate responses; however, these verbal responses were not recorded. This is consistent with fMRI studies where subjects completed the task overtly. In future MEG studies, audio recordings of the subjects’ responses would allow further and more detailed analysis of subject strategy and may capture more subtle sex-related behavioral and neuroimaging differences.

Within the larger context of neuroimaging studies, two recent structural imaging papers report interesting sex differences in brain laterality. Ingalhalikar and colleagues (2014) used fiber tractography and diffusion tensor imaging to compute structural connectectomes in >900 children and young adults (aged 8–22 years). Similar to our findings, they report that males showed strong laterality (intra-hemispheric connectivity) that was established early in life and preserved throughout development. On the other hand, females showed dominant inter-hemispheric connectivity at a young age, and this decreased with increasing age. O’Muircheartaigh and colleagues (2013) used a DTI measure of myelin water content to examine the relation between language ability and myelination asymmetry in 108 children aged 1–6 years. In this very young cohort, they report relations between language measures and subcortical white matter; however, they did not find effects for lateral frontal and temporal areas – possibly these children were too young to have established well their language networks. Our study addresses the gap in age between the former and latter papers, and we find some consistent results and some differences, probably due to development. These three studies taken together emphasize the need for large scale developmental studies that not only consider age as a variable, but take into account sex and individual differences in functional ability.

Conclusion

In this study, differences in the spatiotemporal patterns of language lateralization were found for boys and girls. Boys demonstrated more adult-typical, left-sided patterns across all time windows with a more focal activation in the language-related areas during a verb generation task. This typical language lateralization emerged in early childhood for boys. In contrast, girls exhibited a more bilateral pattern with less ERD in language-related areas during childhood with more adult-typical language lateralization emerging around age 16 years. Our findings concur with behavioral and recent structural neuroimaging studies of sex differences in language function in childhood. Our current results do not suggest that the differences in language lateralization persist into adulthood, but instead may reflect differences in the maturation rates of the development of brain neurophysiology and neuroanatomy between boys and girls. These data emphasize the need to look at both age-related and sex-related factors when studying language acquisition and language function in child development.

One potential application of our finding is in the clinical realm as it may provide a useful reference in pediatric surgery programs where extensive language mapping is performed pre-surgically in a child with left hemisphere disease (e.g., epilepsy, brain tumours) and not considered the standard of care for right hemisphere disease. Our results would suggest that, depending on the child’s age and sex, right hemisphere language involvement needs to be determined as well. Our findings, if confirmed by future studies, would have important implications for clinical care and would require re-consideration of the current standard of care in pediatric epilepsy surgeries. However, these findings are early and require replication before translating into the clinical arena.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant (MOP-89961 to LFD and EWP). The authors would like to thank Marc Lalancette for assistance with data acquisition. Thanks to all the parents and children who participated.

References

- Allendorfer JB, Lindsell CJ, Siegel M, Banks CL, Vannest J, Holland S, Szaflarski JP. Females and males are highly similar in language performance and cortical activation patterns during verb generation. Cortex. 2011;48:1218–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baciu MV, Rubin C, Decorps M, Segebarth CM. fMRI assessment of hemispheric language dominance using a simple inner speech paradigm. NMR in Biomedicine. 1999;12:293–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199908)12:5<293::aid-nbm573>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LC, Saykin AJ, Flashman LA, Johnson SC, Guerin SJ, Babcock DR, Wishart HA. Sex differences in semantic language processing: A functional MRI study. Brain and Language. 2003;84:264–272. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Haynes OM, Painter KM, Genevro JL. Child language with mother and with stranger at home and in the laboratory: A methodological study. Journal of Child Language. 2000;27:407–420. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900004165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer SM, Moran JE, Mason KM, Constantinou JE, Smith BJ, Barkley GL, Tepley N. MEG localization of language-specific cortex utilizing MR-FOCUSS. Neurology. 2004;62(12):2247–2255. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000130385.21160.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer SM, Moran JE, Weiland BJ, Mason KM, Greenwald ML, Smith BJ, Barkley GL, Tepley N. Language laterality determined by MEG mapping with MR_FOCUSS. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2005;6(2):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TT, Lugar HM, Coalson RS, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Developmental changes in human cerebral functional organization for word generation. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:275–290. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Raichle ME, Petersen SE. Dissociation of human prefrontal cortical areas across different speech production tasks and gender groups. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;75:2163–2173. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman DD, Bitan T, Booth JR. Sex differences in neural processing of language among children. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1349–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AM, Rimrodt SL, Abel JR, Blankner JG, Mostofsky SH, Pekar JJ, Denckla MB, Cutting LE. Sex differences in cerebral laterality of language and visuospatial processing. Brain and Language. 2006;98:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D, Waters HS. Sex differences in the use of organization strategies: A developmental analysis. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1986;41:18–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(91)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Beers SR, Hall J, Frustaci K, Masalehdan A, Noll J, Boring AM. Sex differences in brain maturation during childhood and adolescence. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:552–557. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody picture vocabulary test. 3. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dionne G, Dale PS, Boivin M, Plomin R. Genetic evidence for bidirectional effects of early lexical and grammatical development. Child Development. 2003;74:394–412. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulitz C, Maess C, Pantev AD, Frederici B, Freige B, Elbert T. Oscillatory neuromagnetic activity induced by language and non-language stimuli. Cognition and Brain Research. 1996;4:121–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AE, Furlong PL, Seri S, Adjamian P, Witton C, Baldeweg T, Phillips S, Walsh R, Houghton JM, Thai NJ. Interhemispheric differences of spectral power in expressive language: a MEG study with clinical applications. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;68(2):111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JA, Binder JR, Springer JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PSF, Rao SM, Cox RW. Language processing is strongly left lateralized in both sexes: Evidence from functional MRI. Brain. 1999;122:199–208. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard WD, Balsamo LM, Ibrahim Z, Sachs BC, Xu B. fMRI identifies regional specialization of neural networks for reading in young children. Neurology. 2003a;60:94–100. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard WD, Sachs BC, Whitnah JR, Ahmad Z, Balsamo LM, Petrella JR, Braniecki SH, McKinney CM, Hunter K, Xu B, Grandin CB. Developmental aspects of language processing: fMRI of verbal fluency in children and adults. Human Brain Mapping. 2003b;18:176–185. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz W, Macdonald M, Cheyne D, Snead OC. Neuromagnetic imaging of movement-related cortical oscillations in children and adults: age predicts post-movement beta rebound. Neuroimage. 2010;51(2):792–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos R, Makeig S, Talmachoff PJ. A 40 Hz auditory potential recorded from the human scalp. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78:2643–2647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Koenig P, DeVita C, Moore P, Rgee J, Detre J, Alsop D, Gee JC. Neural basis for semantic memory difficulty in Alzheimer’s disease: An fMRI study. Brain. 2002a;126:292, 311. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Smith EE, Koenig P, Glosser G, DeVita C, Moore P, McMillan C. The neural basis for categorization in semenory memory. Neuroimage. 2002b;17:1549–1561. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Alsop D, Glahn D, Petty R, Swanson CL, Maldjian JA, Turetsky BI, Detre JA, Gee J, Gur RE. An fMRI study of sex differences in regional activation to a verbal and a spatial task. Brain and Language. 2000;74:157–170. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington GS, Farias ST. Sex differences in language processing: Functional MRI methodological considerations. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;27:1221–1228. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Kato A, Ninomiya H, Taniguchi M, Kishima H, Yoshimine T. Spatiotemporal distributions of brain oscillation during silent reading. International Congress Series. 2002;1232:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Kato A, Taniguchi M, Saitoh Y, Ninomiya H, Ihara A, Kishima H, Oshino S, Baba T, Yorifuji S, Yoshimine T. Determination of language dominance with synthetic aperture magnetometry: comparison with the Wada test. Neuroimage. 2004;23:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirnstein M, Westerhausen R, Korsnes MS, Hugdahl K. Sex differences in language asymmetry are age-dependent and small: A large-scale, consonant-vowel dichotic listening study with behavioral and fMRI data. Cortex. 2012;49:1910–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland SK, Plante E, Byars AW, Strawsburg RH, Schmithorst VJ, Ball S., Jr Normal fMRI brain activation patterns in children performing a verb generation task. Neuroimage. 2001;14:837–843. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara A, Hirata M, Sakihara K, Izumi H, Takahashi Y, Kono K, Imaoka H, Osaki Y, Kato A, Yoshimine T, Yorifuji S. Gamma-band desynchronization in language area reflects syntactic process of words. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;229:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D, Satterthwaite TD, Elliott MA, Ruparel K, Hakonarson H, Gur RE, Gur RC, Verma R. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;111(2):823–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger JJ, Lockwood AH, Van Valin RD, Jr, Kemmerer DL, Murphy BW, Wack DS. Sex differences in brain regions activated by grammatical and reading tasks. Neuroreport. 1998;9:2803–2807. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199808240-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadis DS, Smith ML, Mills T, Pang EW. Expressive language mapping in children using MEG. Down Syndrome Quarterly. 2008;10:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kadis DS, Pang EW, Mills T, Taylor MJ, McAndrews MP, Smith ML. Characterizing the normal developmental trajectory of expressive language lateralization using MEG. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011;17:896–904. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada K, Sawamura Y, Takeuchi F, Kuriki S, Kawai K, Morita A, Todo T. Expressive and receptive language areas determined by a non-invasive reliable method using functional magnetic resonance imaging and magnetoencephalography. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(2):296–305. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249262.03451.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansaku K, Kitazawa S. Imaging studies on sex differences in the lateralization of language. Neuroscience Research. 2001;41:333–337. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi M, Shitamichi K, Yoshimura Y, Ueno S, Remijn GB, Hirosawa T, Munesue T, Tsubokawa T, Haruta Y, Oi M, Higashida H, Minabe Y. Lateralized theta wave connectivity and language performance in 2- to 5-year-old children. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(42):14984–14988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2785-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Sex and Cognition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa S, Kansaku K. Sex difference in language lateralization may be task-dependent. Brain. 2005:e30. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht S, Drager B, Deppe M, Bobe L, Lohmann H, Floel A, Ringelstein EB, Henningsen H. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain. 2000;123(pt 12):2512–1518. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht S, Jansen A, Frank A, van Randenborgh J, Sommer J, Kanowski M, Heinze H. How atypical is atypical language dominance? Neuroimage. 2003;18:917–927. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Delis DC, Kaplan E, O’Donnell L, Prifitera A. Developmental sex differences in verbal learning. Neuropsychology. 1997;11:577–584. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Delis DC, Daniel M. Sex differences in verbal learning. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1988;44:907–915. [Google Scholar]

- Kunii N, Kamada K, Ota T, Greenblatt RE, Kawai K, Saito N. The dynamics of language-related high-gamma activity assessed on a spatially-normalized brain. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2013;124:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. Sex differences in the adolescent brain. Brain cognition. 2010;71:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot RK, Gogtay N, Greenstein DK, Wells EM, Wallace GL, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, Lerch J, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC, Thompson PM, Giedd JN. Sexual dimorphism of brain developmental trajectories during childhood and adolescence. Neuroimage. 2007;36:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzenberger W, Pulvermuller F, Birbaumer N. Words and pseudowords elicited distinct pattern of 30 Hz activity in human. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;176:115–118. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90884-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MM, Bosch J, Elbert T, Kreiter A, Sosa V, Sosa PV, Rockstroh B. Visually induced gamma-band responses in human electroencephalographic activity: a link to animal studies. Experimental Brain Research. 1996;112:96–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00227182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olga S, Weis S, Krings T, Huber W, Kircher T. Categorical and thematic knowledge representation in the brain: Neural correlates of taxonomic and thematic conceptual relations. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh J, Dean DC, III, Dirks H, Waskiewicz N, Lehman K, Jerskey BA, Deoni SCL. Interactions between white matter asymmetry and language during neurodevelopment. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(41):16170–16177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1463-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang EW. Practical aspects of running development studies in the MEG. Brain Topography. 2011;24(3–4):253–60. doi: 10.1007/s10548-011-0175-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang EW, Wang F, Malone M, Kadis DS, Donner EJ. Localization of Broca’s area using verb generation tasks in the MEG: validation against fMRI. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;490(3):215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin JS, Leonard G, Perron M, Pike GB, Pitiot A, Richer L, Veillette S, Pausova Z, Paus T. Sex differences in the growth of white matter during adolescence. Neuroimage. 2009;45:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller G, Lopes da Silva FH. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles. Clinical Neurophysiology. 1999;110:1842–1857. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirmoradi M, Béland R, Nguyen DK, Bacon BA, Lassonde M. Language tasks used for the presurgical assessment of epileptic patients with MEG. Epileptic Disorders. 2010;12(2):97–108. doi: 10.1684/epd.2010.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante E, Schmothorst VJ, Holland SK, Byars AW. Sex differences in the activation of language cortex during childhood. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:1210–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Deus J, Losilla JM, Capdevila A. Cerebral lateralization of language in normal left-handed people studied by functional MRI. Neurology. 1999;52:1038–1043. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvermuller F, Eulitz C, Pantev C, Mohr B, Feige B, Lutzenberger W, Thomas E, Birbaumer N. High-frequency cortical responses reflect lexical processing: an MEG stud. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology. 1996;98:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(95)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvermuller F, Lutzenberger W, Preissl H, Birbaumer N. Spectrum responses in the gamma-band: physiological signs of higher cognitive processes. Neuroreport. 1995;6:2059–2064. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199510010-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressel V, Wilke M, Lidzba K, Lutzenberger W, Krageloh-Mann I. Increases in language lateralization in normal children as observed using magneteoencephalography. Brain and Language. 2008;106:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressel V, Wilke M, Lidzba K, Preissl H, Krägeloh-Mann I, Lutzenberger W. Language lateralization in magnetoencephalography: two tasks to investigate hemispheric dominance. Neuroreport. 2006;17(11):1209–1213. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000230506.32726.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SE, Vrba J. Functional neuroimaging by synthetic aperture magnetometry (SAM) In: Yoshimine T, Kotani M, Kuriki S, Karibe H, Nakasato N, editors. Recent Advances in Biomagnetism. Sendai: Tokoku Univesity Press; 1999. pp. 302–305. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai KL. Language acquisition and brain development. Science. 2005;310:815–819. doi: 10.1126/science.1113530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Pugh KR, Constable RT, Skudlarski P, Fulbright RK, Bronen RA, Fletcher JM, Shankweiler DP, Katz L, Gore JC. Sex differences in the functional organization of the brain for language. Nature. 1995;373:607–609. doi: 10.1038/373607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spironelli C, Penolazzi B, Angrilli A. Gender differences in reading in school-aged children: An early ERP study. Developmental neuropsychology. 2010;35:357–375. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.480913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Bibder JR, Possing ET, McKiernan KA, Ward BD, Hammeke TA. Language lateralization in left-handed and ambidextrous people: fMRI data. Neurology. 2002;59:238–244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Holland SK, Schmithorst VJ, Byars AW. fMRI study of language lateralization in children and adults. Human Brain Mapping. 2006;27:202–212. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Rajagopal A, Altaye M, Byars AW, Jacola L, Schmithorst VJ, Schapiro MB, Plante E, Holland SK. Left-handedness and language lateralization in children. Brain Research. 2012;1433:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiitinen H, Sinkkonen J, Reinikainen K, Alho K, Lavikainen J, Naatanen R. Selective attention enhances the auditory 40 Hz responses in humans. Nature. 1993;364:59–60. doi: 10.1038/364059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrba J, Robinson SE. Signal processing in magnetoencephalography. Methods. 2001;25:249–271. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Holland SK, Vannest J. Concordance of MEG and fMRI patterns in adolescents during verb generation. Brain Research. 2012;1447:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss EM, Siedentopf C, Hofer A, Deisenhammer EA, Hoptman MJ, Kremser C, Golaszewski S, Felber S, Fleischhacker WW, Delazer M. Brain activation pattern during a verbal fluency test in healthy male and female volunteers: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;352:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KT. Expressive vocabulary test. Circle Pines, MN: American Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yordanova J, Kolev V, Heinrich H, Woerner W, Banaschewski T, Rothenberger A. Developmental event-related gamma oscillations: effects of auditory attention. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;16(11):2214–2224. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]