Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is an alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis who are at high risk of perioperative mortality. Previous studies showed increased risk of postoperative AKI with TAVR, but it is unclear whether differences in patient risk profiles confounded the results. To conduct a propensity-matched study, we identified all adult patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis at Mayo Clinic Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota from January 1, 2008 to June 30, 2014. Using propensity score matching on the basis of clinical characteristics and preoperative variables, we compared the postoperative incidence of AKI, defined by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines, and major adverse kidney events in patients treated with TAVR with that in patients treated with SAVR. Major adverse kidney events were the composite of in-hospital mortality, use of RRT, and persistent elevated serum creatinine ≥200% from baseline at hospital discharge. Of 1563 eligible patients, 195 matched pairs (390 patients) were created. In the matched cohort, baseline characteristics, including Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score and eGFR, were comparable between the two groups. Furthermore, no significant differences existed between the TAVR and SAVR groups in postoperative AKI (24.1% versus 29.7%; P=0.21), major adverse kidney events (2.1% versus 1.5%; P=0.70), or mortality >6 months after surgery (6.0% versus 8.3%; P=0.51). Thus, TAVR did not affect postoperative AKI risk. Because it is less invasive than SAVR, TAVR may be preferred in high-risk individuals.

Keywords: acute renal failure, outcomes, cardiovascular disease

The occurrence of AKI after cardiac surgery, particularly aortic valve replacement, results in longer length of hospital stay and increased use of hospital resources1 and is independently associated with short- and long-term mortality.2,3 Despite many attempts to identify effective interventions to prevent postoperative AKI,4–6 the incidence of AKI after cardiac surgery is reported to remain as high as 30%.7,8

Since the first successful surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in 1960,9 SAVR has remained the gold standard treatment for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis.10 However, there is a number of patients with comorbidities who will not undergo SAVR because of a high risk of perioperative mortality. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has emerged as an alternative option for these high-risk patients.10,11 Patients selected for TAVR typically have higher comorbidities, including CKD, which may carry a higher risk for AKI.12 Because TAVR is a less invasive procedure than SAVR, the hope is that TAVR might provide a lower risk of postoperative AKI. Unfortunately, the evidence for the renal protective effect of TAVR is still unsettled. Indeed, several studies have shown a higher incidence of postoperative AKI among patients who underwent TAVR compared with those who had SAVR.13,14 However, these results might be confounded by selection bias, because the patients who underwent TAVR usually had more comorbid conditions, many of which are associated with higher postoperative AKI.

The objective of this propensity-matched study was to assess the risk of AKI in patients who underwent TAVR compared with matched patients who underwent SAVR. We used propensity score matching to ensure comparability and similar risk profiles between the groups. In addition, we report the risk of AKI after TAVR in a large cohort of patients with severe aortic stenosis who required valve replacement.

Results

During the study period, 1586 patients underwent aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Of these patients, 20 who had ESRD or had received dialysis within 14 days before surgery and 3 with no research authorization were excluded. In total, 1563 patients (386 in the TAVR group and 1177 in the SAVR group) were included in the initial cohort before matching (Figure 1). In the unmatched cohort, patients with TAVR were significantly older, had a higher Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score, had more comorbid conditions, and had more prevalence of previous cardiac surgery; in addition, patients with TAVR had a lower baseline eGFR, ejection fraction, and aortic valve gradient compared with patients with SAVR (Table 1). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the rate of all blood product transfusion among patients with TAVR and patients with SAVR. One third of the whole cohort required transfusion. Transfusion rate among patients with TAVR was only 22.5%, whereas 35.6% of patients with SAVR received a transfusion (P<0.001). There was no statistical difference between the two groups for platelet transfusion, and there was a trend toward a higher rate of fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate transfusion among patients with SAVR (P=0.05 and P=0.08, respectively). Patients with TAVR received more red blood cell transfusions compared with patients with SAVR (mean, 2.8±3.6 versus 2.2±2.5; P=0.03). The average duration of procedure in TAVR was less than in SAVR (127±52 versus 191±63; P<0.001).

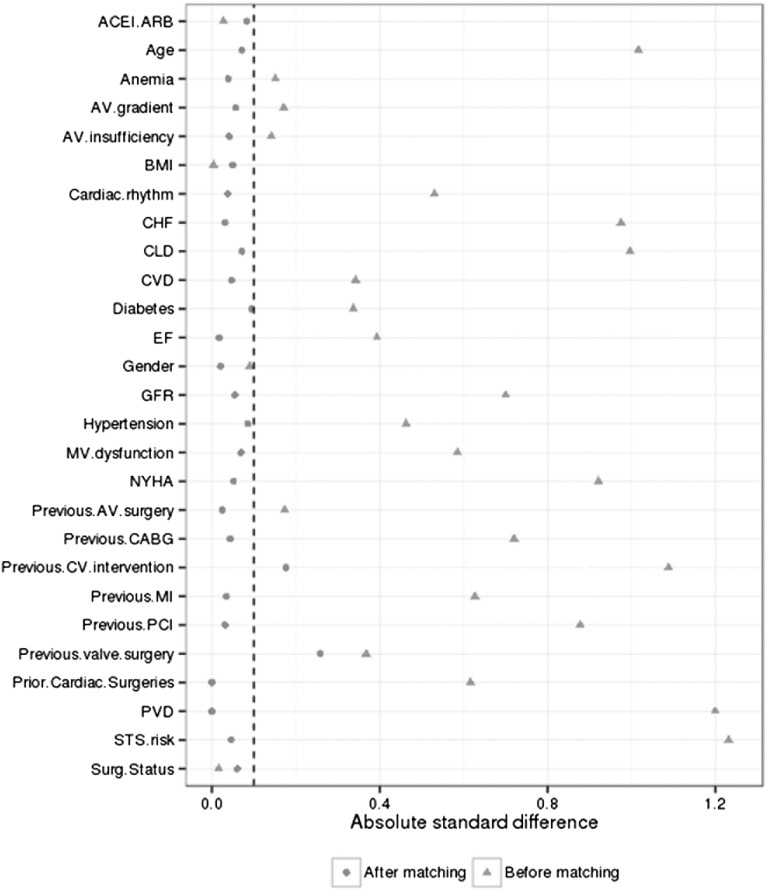

Figure 1.

The plot of absolute standard difference before and after propensity score matching. ACEI, angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AV, aortic valve; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHF, congestive heart failure; CLD, chronic liver disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; EF, ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MV, mitral valve; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular diseases; Surg status, surgical status.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching

| Baseline Characteristics | Before Propensity Matching | After Propensity Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVR (n=386) | SAVR (n=1177) | P Value | TAVR (n=195) | SAVR (n=195) | P Value | |

| STS risk score | 8.6±6.3 | 2.6±2.8 | <0.001 | 6.3±4.6 | 6.2±4.6 | 0.65 |

| Age (yr) | 81±8 | 71±12 | <0.001 | 80±9 | 80±8 | 0.48 |

| Men | 217 (56) | 714 (61) | 0.12 | 103 (53) | 105 (54) | 0.84 |

| White | 374 (97) | 1099 (93) | 0.01 | 185 (95) | 177 (91) | 0.12 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.4±7.5 | 30.3±6.7 | 0.95 | 30.1±7.6 | 30.4±7.0 | 0.63 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 55±21 | 69±19 | <0.001 | 57±51 | 56±19 | 0.59 |

| NYHA classes 3 and 4 | 335 (87) | 559 (47) | <0.001 | 154 (79) | 158 (81) | 0.61 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| DM | 157 (41) | 295 (25) | <0.001 | 73 (37) | 82 (42) | 0.35 |

| HTN | 349 (90) | 859 (73) | <0.001 | 173 (89) | 178 (91) | 0.40 |

| Dyslipidemia | 346 (90) | 980 (83) | 0.002 | 167 (86) | 178 (91) | 0.08 |

| MI | 139 (36) | 126 (11) | <0.001 | 53 (27) | 56 (29) | 0.74 |

| CHF | 223 (58) | 183 (16) | <0.001 | 81 (42) | 84 (43) | 0.76 |

| CVD | 110 (28) | 172 (15) | <0.001 | 47 (24) | 51 (26) | 0.64 |

| PVD | 226 (59) | 115 (10) | <0.001 | 76 (39) | 76 (39) | >0.99 |

| Anemia | 10 (3) | 8 (1) | 0.002 | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.70 |

| CLD | 240 (62) | 217 (18) | <0.001 | 104 (53) | 97 (50) | 0.48 |

| Smoking within 1 yr | 11 (3) | 81 (7) | 0.004 | 5 (3) | 11 (6) | 0.13 |

| Prior cardiac intervention | ||||||

| PCI | 199 (52) | 163 (14) | <0.001 | 80 (41) | 77 (39) | 0.76 |

| Cardiac surgery | 181 (47) | 225 (19) | <0.001 | 72 (37) | 73 (37) | 0.92 |

| CABG | 167 (43) | 151 (13) | <0.001 | 62 (32) | 66 (34) | 0.67 |

| Valve surgery | 84 (22) | 103 (9) | <0.001 | 30 (15) | 21 (11) | 0.18 |

| AV surgery | 10 (3) | 72 (6) | 0.01 | 9 (5) | 8 (4) | 0.80 |

| Echocardiographic finding | ||||||

| EF | 56±13 | 61±11 | <0.001 | 57±13 | 57±13 | 0.86 |

| AV gradient | 48±14 | 50±15 | 0.003 | 49±15 | 50±14 | 0.58 |

| AV insufficiency | 209 (54) | 646 (55) | 0.80 | 101 (52) | 109 (56) | 0.42 |

| Myocardial dysfunction | 300 (78) | 598 (51) | <0.001 | 146 (75) | 140 (72) | 0.49 |

| Preoperative medication | ||||||

| ACEI/ARB | 157 (41) | 466 (40) | 0.64 | 81 (42) | 89 (46) | 0.41 |

| β-Blocker | 266 (69) | 517 (44) | <0.001 | 132 (68) | 117 (60) | 0.11 |

| Statin | 281 (73) | 744 (63) | 0.001 | 133 (68) | 148 (76) | 0.09 |

| Aspirin | 284 (74) | 719 (61) | <0.001 | 131 (67) | 143 (73) | 0.18 |

| Normal sinus rhythm | 280 (73) | 1084 (92) | <0.001 | 152 (78) | 155 (79) | 0.71 |

| Elective surgery | 368 (96) | 1126 (96) | 0.78 | 180 (92) | 183 (94) | 0.55 |

Continuous variable are reported as means±SDs. Categorical variable are reported as count (%). BMI, body mass index; NYHA, New York Heart Association; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; CLD, chronic lung disease; PCI, percutaneous cardiac intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; AV, aortic valve; EF, ejection fraction; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker.

In the entire cohort, postoperative AKI occurred in 106 (27.5%) patients with TAVR, with 22.0% in stage 1, 1.6% in stage 2, and 3.9% in stage 3. In contrast, postoperative AKI occurred in 224 (19.0%) patients with SAVR, with 17% in stage 1, 1.7% in stage 2, and 0.3% in stage 3 (Table 2).

Table 2.

AKI and in-hospital outcomes before and after propensity matching

| Outcomes | Before Propensity Matching | After Propensity Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVR (n=386) | SAVR (n=1177) | P Value | TAVR (n=195) | SAVR (n=195) | P Value | |

| AKI | 106 (27.5) | 224 (19.0) | <0.001 | 47 (24.1) | 58 (29.7) | 0.21 |

| AKI stage | <0.001 | 0.28 | ||||

| No AKI | 280 (72.5) | 953 (81.0) | 148 (75.9) | 137 (70.3) | ||

| Stage 1 | 85 (22.0) | 200 (17.0) | 39 (20.0) | 53 (27.2) | ||

| Stage 2 | 6 (1.6) | 20 (1.7) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Stage 3 | 15 (3.9) | 4 (0.3) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| RRT in hospital | 11 (2.9) | 5 (0.4) | <0.001 | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | >0.99 |

| In-hospital mortality | 11 (2.9) | 2 (0.2) | <0.001 | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0.65 |

| Major adverse kidney event | 18 (4.7) | 8 (0.7) | <0.001 | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0.70 |

| Hospital length of stay (d) | 7.0±5.0 | 7.2±3.2 | 0.45 | 6.5±3.4 | 8.8±4.3 | <0.001 |

| 6-mo Mortalitya | 10.7% | 2.5% | <0.001 | 6.0% | 8.3% | 0.62 |

| eGFR at 6 mob | 54±20 | 72±21 | <0.001 | 55±19 | 58±20 | 0.09 |

| Chronic renal replacement at 6 mob | 7 (2.0) | 6 (0.5) | 0.01 | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0.57 |

Data are presented as numbers (percentages) of patients or means±SDs unless otherwise indicated.

Percentages were derived from Kaplan–Meier plots.

Analysis was limited in survivors at 6 months after surgery.

CKD played a significant role as a risk factor for AKI in both TAVR and SAVR cohorts. We also noted a dose-response relationship between the incidence of AKI and progressive stages of CKD (Table 3). Among patients who developed stage 2 or 3 AKI, urine examination was available in 62% (28 of 45). Among patients with available urine examination, renal tubular epithelium or granular cast was present in 71% (20 of 28), suggesting acute tubular necrosis as the etiology of AKI. Serum eosinophilia was more common in the TAVR than in the SAVR group (4% versus 1%; P<0.001).

Table 3.

The relationship between CKD and incidence of AKI

| Group | CKD Stages | P Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| N | AKI | N | AKI | N | AKI | N | AKI | ||

| All | 176 | 25 (14) | 771 | 122 (16) | 554 | 149 (27) | 62 | 34 (55) | <0.001 |

| TAVR | 19 | 3 (16) | 135 | 26 (19) | 194 | 53 (27) | 38 | 24 (63) | <0.001 |

| SAVR | 157 | 22 (14) | 636 | 96 (15) | 360 | 96 (27) | 24 | 10 (42) | <0.001 |

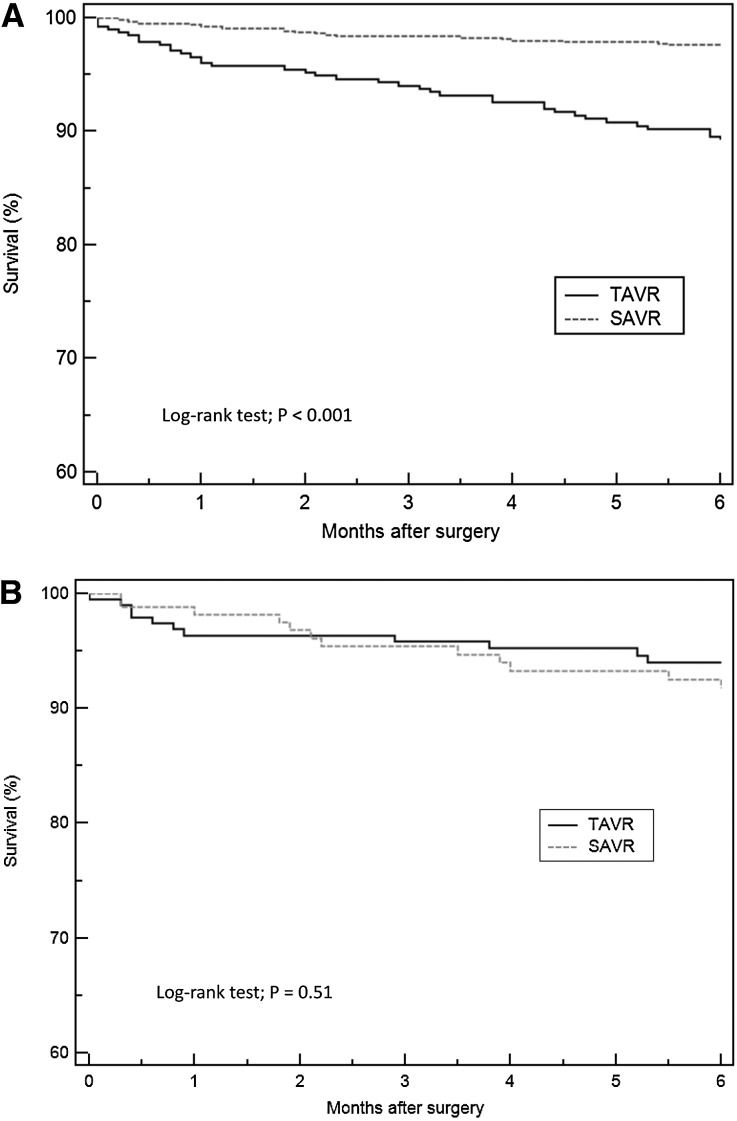

In unadjusted analysis, AKI occurrence in the TAVR group was significantly higher than in the SAVR group (relative risk, 1.44; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.18 to 1.76; P<0.001). The TAVR group had higher in–hospital mortality (2.9% versus 0.2%; P<0.001), need for RRT (2.9% versus 0.4%; P<0.001), and major adverse kidney events (4.7% versus 0.7%; P<0.001). The 6-month mortality was 10.7% for the TAVR group and 2.5% for the SAVR group (P<0.001) (Figure 2A). In adjusted analysis, there was no significant difference in AKI occurrence rate between TAVR and SAVR groups (adjusted odds ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.48 to 1.01; P=0.06).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot showing survival in TAVR and SAVR groups. (A) Mortality difference between TAVR versus SAVR in unadjusted analysis. (B) Mortality difference between TAVR versus SAVR following propensity matching.

Propensity score matching created a matched cohort of 195 patients in each group. In this matched cohort, baseline characteristics and preoperative variables were comparable between the TAVR and SAVR groups (Table 1). In the matched cohort, postoperative AKI occurred in 47 (24.1%) patients with TAVR; 20% of these patients were in stage 1, 1.5% were in stage 2, and 2.6% were in stage 3. In the SAVR cohort, AKI occurred in 58 (29.7%) patients, with 27.2% in stage 1, 1.5% in stage 2, and 1% in stage 3. There was no significant difference in postoperative AKI between the TAVR and SAVR groups (relative risk, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.13; P=0.21) as shown in Table 2. There were also no significant differences in in-hospital mortality (1.5% versus 1%; P=0.65), need for RRT (1% versus 1%; P>0.99), or major adverse kidney events (2.1% versus 1.5%; P=0.70) between the TAVR and SAVR groups. The mean hospital length of stay in TAVR group was shorter than in SAVR group (6.5±3.4 versus 8.8±4.3 days; P<0.001). The 6-month mortality was 6% for the TAVR group and 8.3% for the SAVR group (P=0.51) (Figure 2B). Among patients who survived at 6 months after surgery, there were no significant differences in eGFR and the need for chronic RRT at 6 months.

Discussion

Using comprehensive propensity score analysis, we found no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative AKI, severe AKI requiring RRT, major adverse kidney events, in-hospital mortality, or 6-month survival among patients undergoing TAVR versus SAVR. For patients who had a significant number of comorbid conditions, we found no difference in the risk of AKI between TAVR and SAVR. Before matching, we noted that patients with TAVR were significantly older, carried higher STS risk scores, and had more comorbid conditions compared with patients with SAVR.

When only a limited number of confounders was taken into account, such as the STS risk score, previous studies found a significantly higher incidence of AKI among patients who underwent TAVR.13,14 We showed that, using a robust propensity score–matched analysis incorporating the STS risk score along with other known AKI risk factors, the higher incidence of postoperative AKI, severe AKI requiring RRT, or major adverse kidney events among patients with TAVR disappears.

Patients undergoing SAVR reported to encounter a higher rate of periprocedural transfusions, and they need cardiopulmonary bypasses,15,16 which are both associated with generation of thrombin, inflammatory reaction, and increased postoperative bleeding, all of which can lead to AKI development.17 During cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, upregulation of adhesion molecules, such as CD11b and CD41, platelet activation, and release of cytotoxic oxygen–derived free radicals, proteases, cytokines, and chemokines can lead to significant inflammatory response.7 At the time of aortic cannulation, the chance of microscopic and macroscopic embolic events is high.18 This per se can increase the risk of AKI and after maladaptive repair, lead to CKD. In addition, high risk of hemodynamic instability during SAVR and the effect of hypothermia, nonpulsatile blood flow, and euvolemic hemodilution during open heart surgery on the kidney hemodynamics have been considered risk factors of AKI after SAVR. In a study of patients with cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, investigators suggested that mean arterial pressure >70 mmHg was associated with higher intraoperative creatinine clearance when it was compared with the mean arterial pressure of 50–60 mmHg.7,19 Although TAVR is associated with fewer hemodynamic and inflammatory changes, it could still be associated with increased risk of AKI because of contrast exposure, atheroembolic events, and hemodynamic instability when the valve placement does not occur appropriately.10 Interestingly, three separate randomized, controlled studies have shown different rates of postoperative AKI.10,20,21 Two of the mentioned trials showed no significant difference in postoperative AKI between the TAVR and SAVR groups.20,21 One explanation could be differences in AKI definitions, which can affect the AKI incidence between studies.8 One study with the standard AKI definition6 showed a significantly reduced AKI risk in the TAVR group. This suggests a potential benefit of TAVR utilization to reduce AKI risk.

Despite the trend of reduction in postoperative AKI risk in the TAVR group in our study, this effect did not translate to a decrease in severe AKI requiring RRT. Comparable survival within 6 months between the TAVR and SAVR groups was consistent with previous meta-analyses.16,22 Because the majority of patients who underwent TAVR have significant comorbid conditions, they could have had a higher risk of mortality and AKI if they would have undergone SAVR, or they could have been considered inoperable. Our analysis highlighted that a minimally invasive and less expensive procedure (i.e., TAVR) is not associated with increased risk of complications that are traditionally related to aortic valve replacement.

There are several limitations to our study. (1) This is a single–center, retrospective study. (2) Although our report is the largest propensity score–matched study in the current literature, our limited sample size could underpower our conclusions. (3) We did not include urine output criterion for AKI diagnosis, because an indwelling urinary catheter was not used to obtain accurate hourly urine output data for a large percentage of patients in our cohort. Therefore, the results of this study ultimately need to be validated in a larger, multicenter prospective study.

Our study also has several strengths. We used a very robust propensity–matching method to compare the outcomes among the two groups while removing the effects of other confounders. In addition, our cohort is the largest cohort published in the literature.

In a large, single–center, propensity–matched study, we found that, among patients who have high risk for AKI, TAVR is not associated with higher incidence of AKI, mortality, or need for RRT compared with SAVR. Considering the high incidence of complications associated with open and on–pump surgical procedures and longer time required for recovery, we conclude that TAVR as a less invasive and expensive procedure is an appropriate alternative for SAVR among high-risk patients.

Concise Methods

Study Population

This is a single–center, retrospective study conducted at a tertiary referral hospital. We studied all adult patients (age ≥18 years old) who underwent isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis at Mayo Clinic Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota from January 1, 2008 to June 30, 2014. We excluded patients who had ESRD or received any RRT within 14 days before surgery. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The informed consent was waived for patients who already provided research authorization. Patients without research authorization were excluded.

Data Collection

Clinical characteristics, demographic information, and laboratory data were collected using manual and automated retrieval from institutional electronic medical records. The risk of operative mortality was calculated on the basis of patient demographics, preoperative clinical characteristics, and procedures using the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery risk calculator.11,23,24 The eGFR was derived using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.25 CKD was defined as an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Serum eosinophilia was defined as absolute eosinophil count ≥500 cells/μl.

Clinical Outcomes

The primary outcome was postoperative AKI. We defined and staged AKI solely on the basis of the serum creatinine criterion of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Foundation; AKI was defined as an increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dl within 48 hours after surgery or a relative increase of ≥50% from the baseline within 7 days after surgery. The baseline values for serum creatinine were obtained as follows. If outpatient serum creatinine measured between 180 and 7 days before surgery was available, the most recent value was used. Otherwise, the lowest value within the 5 days before surgery was used. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital mortality, need for RRT at any time during hospitalization, composite outcome of major adverse kidney events, and 6-month mortality after surgery. We defined major adverse kidney events as the composite of in-hospital death, use of RRT, and persistence of renal dysfunction (defined by serum creatinine ≥200% of reference) at hospital discharge.

Among patients who survived at 6 months after surgery, we assessed renal function by calculating eGFR at 6 months and the need for chronic dialysis. We imputed an eGFR value of 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at 6 months for any patients who needed chronic dialysis.

Statistical Analyses

All continuous variables were reported as means±SDs. All categorical variables were reported as counts with percentages. For patients with multiple aortic valve replacement surgery, only the first surgery during the study period was included in the analysis. The differences in clinical characteristics and outcomes between patients in the TAVR and SAVR groups were assessed using the t test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. A survival model was initiated at the time of surgery and followed until death or last follow-up time up to 6 months after surgery. Survival was presented using the Kaplan–Meier plot and compared using the log-rank test. The multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess the association between intervention groups (TAVR versus SAVR) and AKI adjusting for variables with statistically significant difference in the univariate analysis. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% CIs were reported. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To further reduce the effect of the preoperative difference between the two groups, a matched cohort of patients treated with TAVR and SAVR was created using propensity score matching.26 Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression with TAVR as the dependent variable on the following covariates: STS risk score, eGFR, sex, body mass index, type of surgery (elective versus urgent/emergency), presence of anemia, history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, New York Heart Association class (classes 1 and 2 versus 3 and 4), preoperative use of angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, previous percutaneous cardiac intervention, previous coronary bypass grafting, previous aortic valve surgery, cardiac rhythm at surgery (normal versus other), and aortic valve insufficiency (none or trivial versus mild, moderate, or severe). Matching was performed in R statistical software (version 3.1.1; R, Vienna, Austria).27 Patients in the TAVR and SAVR groups were matched on a 1:1 basis on the logit of the propensity score with a caliper width equal to 0.2 SD of the logit of the propensity score.28 Covariate balance in the matched sample was assessed using the absolute standard difference, with an absolute standard difference of <0.1 considered to denote a negligible imbalance in covariates between the TAVR and SAVR groups (Figure 1).29,30 Apart from propensity score matching, analyses were performed using JMP statistical software (version 10; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Disclosures

Mayo Clinic foundation provided a small internal grant (CCRKITAVR, 14-007804) for statistical analysis support. No other funding was provided by any intra or extramural entity.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW: Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3365–3370, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricci Z, Cruz D, Ronco C: The RIFLE criteria and mortality in acute kidney injury: A systematic review. Kidney Int 73: 538–546, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricci Z, Cruz DN, Ronco C: Classification and staging of acute kidney injury: Beyond the RIFLE and AKIN criteria. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 201–208, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Srivali N, O’Corragain OA, Edmonds PJ, Ungprasert P, Kittanamongkolchai W, Erickson SB: Preoperative renin-angiotensin system inhibitors use linked to reduced acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 978–988, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yacoub R, Patel N, Lohr JW, Rajagopalan S, Nader N, Arora P: Acute kidney injury and death associated with renin angiotensin system blockade in cardiothoracic surgery: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 1077–1086, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng X, Tong J, Hu Q, Chen S, Yin Y, Liu Z: Meta-analysis of the effects of preoperative renin-angiotensin system inhibitor therapy on major adverse cardiac events in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 47: 958–966, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosner MH, Okusa MD: Acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 19–32, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Akhoundi A, Ahmed AH, Kashani KB: Actual versus ideal body weight for acute kidney injury diagnosis and classification in critically ill patients. BMC Nephrol 15: 176, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harken DE, Soroff HS, Taylor WJ, Lefemine AA, Gupta SK, Lunzer S: Partial and complete prostheses in aortic insufficiency. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 40: 744–762, 1960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, Yakubov SJ, Coselli JS, Deeb GM, Gleason TG, Buchbinder M, Hermiller J Jr., Kleiman NS, Chetcuti S, Heiser J, Merhi W, Zorn G, Tadros P, Robinson N, Petrossian G, Hughes GC, Harrison JK, Conte J, Maini B, Mumtaz M, Chenoweth S, Oh JK U.S. CoreValve Clinical Investigators : Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med 370: 1790–1798, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, Filardo G, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, Normand SL, DeLong ER, Shewan CM, Dokholyan RS, Peterson ED, Edwards FH, Anderson RP Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force : The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: Part 2--isolated valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 88[Suppl]: S23–S42, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh P, Rifkin DE, Blantz RC: Chronic kidney disease: An inherent risk factor for acute kidney injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1690–1695, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holzhey DM, Shi W, Rastan A, Borger MA, Hänsig M, Mohr FW: Transapical versus conventional aortic valve replacement--a propensity-matched comparison. Heart Surg Forum 15: E4–E8, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauch JT, Scherner M, Haldenwang PL, Madershahian N, Pfister R, Kuhn EW, Liakopoulos OJ, Wippermann J, Wahlers T: Transapical minimally invasive aortic valve implantation and conventional aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 60: 335–342, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onorati F, D’Errigo P, Grossi C, Barbanti M, Ranucci M, Covello DR, Rosato S, Maraschini A, Santoro G, Tamburino C, Seccareccia F, Santini F, Menicanti L OBSERVANT Research Group : Effect of severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction on hospital outcome after transcatheter aortic valve implantation or surgical aortic valve replacement: Results from a propensity-matched population of the Italian OBSERVANT multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147: 568–575, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biondi-Zoccai G, Peruzzi M, Abbate A, Gertz ZM, Benedetto U, Tonelli E, D’Ascenzo F, Giordano A, Agostoni P, Frati G: Network meta-analysis on the comparative effectiveness and safety of transcatheter aortic valve implantation with CoreValve or Sapien devices versus surgical replacement. Heart Lung Vessel 6: 232–243, 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boisclair MD, Lane DA, Philippou H, Esnouf MP, Sheikh S, Hunt B, Smith KJ: Mechanisms of thrombin generation during surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood 82: 3350–3357, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sreeram GM, Grocott HP, White WD, Newman MF, Stafford-Smith M: Transcranial Doppler emboli count predicts rise in creatinine after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 18: 548–551, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urzua J, Troncoso S, Bugedo G, Canessa R, Muñoz H, Lema G, Valdivieso A, Irarrazaval M, Moran S, Meneses G: Renal function and cardiopulmonary bypass: Effect of perfusion pressure. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 6: 299–303, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock S PARTNER Trial Investigators : Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 363: 1597–1607, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V, Thourani VH, Corso P, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock SJ PARTNER Trial Investigators : Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 364: 2187–2198, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagaraja V, Raval J, Eslick GD, Ong AT: Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised trials. Open Heart 1: e000013, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahian DM, Edwards FH: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: Introduction. Ann Thorac Surg 88[Suppl]: S1, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Filardo G, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, Normand SL, DeLong ER, Shewan CM, Dokholyan RS, Peterson ED, Edwards FH, Anderson RP Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force : The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: Part 3--valve plus coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 88[Suppl]: S43–S62, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB: The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70: 41–55, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekhon JS: Multivariate and propensity score matching software for causal inference. J Stat Software 42: 1–52, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin PC: Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat 10: 150–161, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, McNeil BJ: Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: A matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol 54: 387–398, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin PC: Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 28: 3083–3107, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]