Abstract

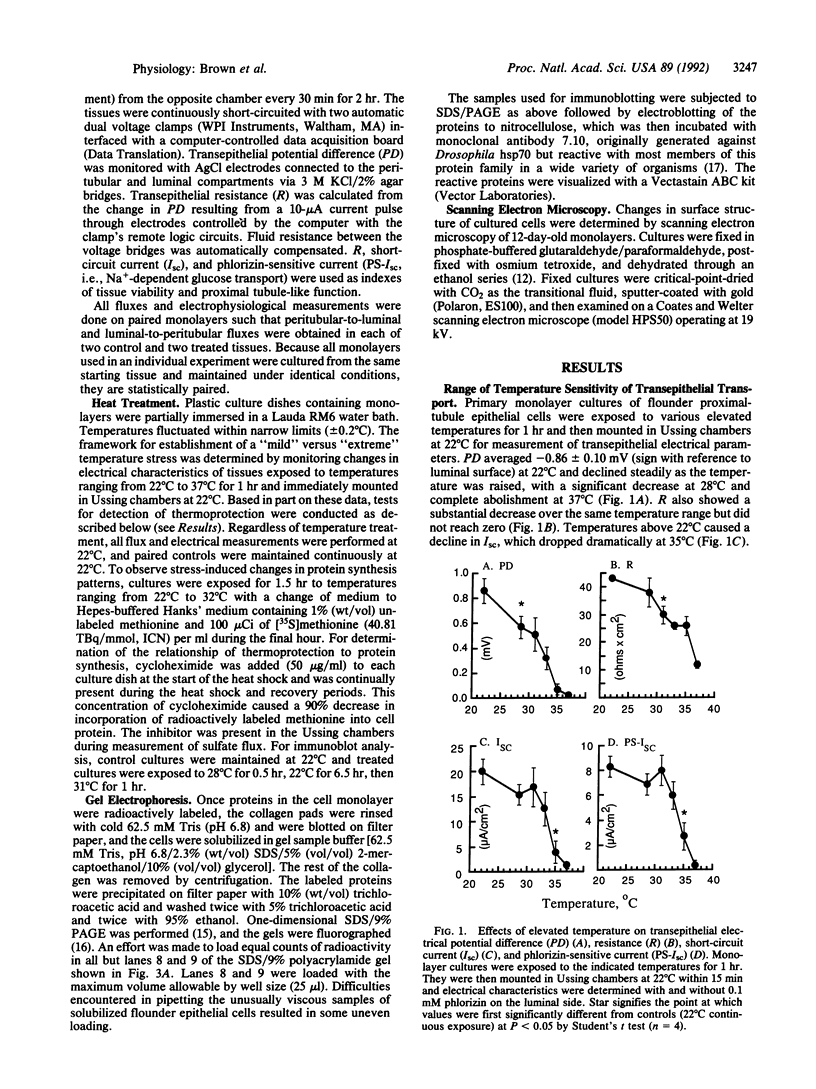

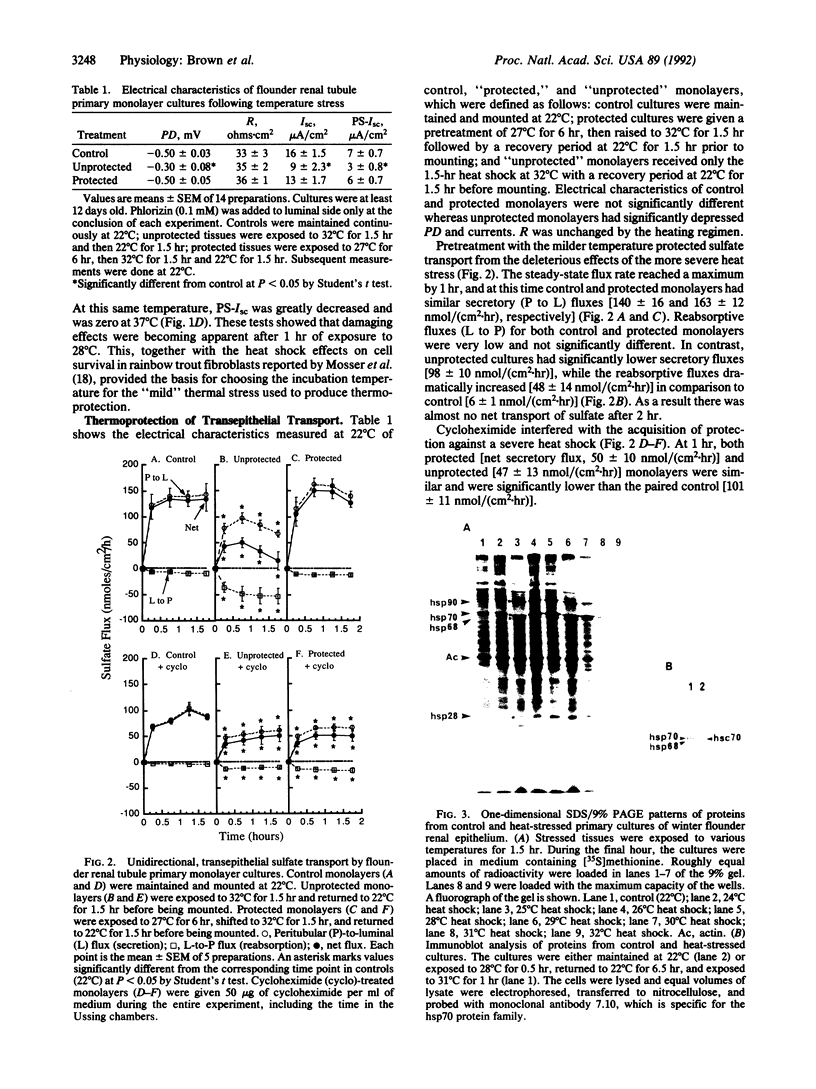

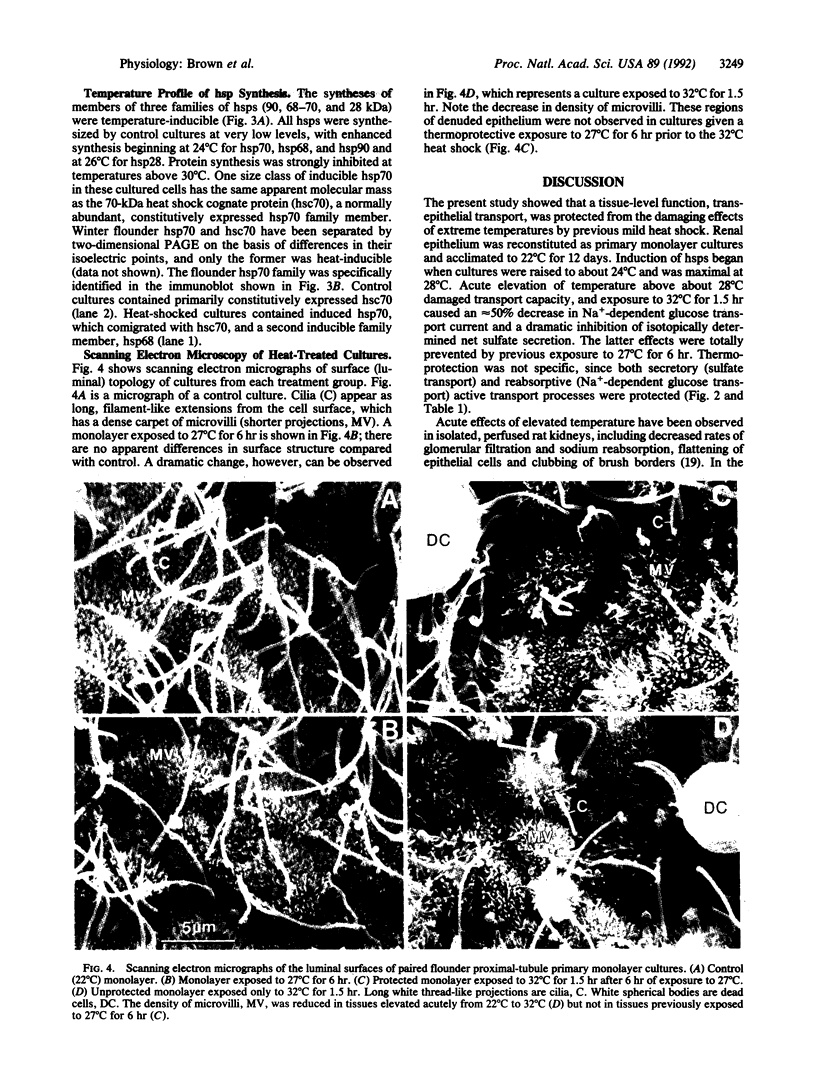

Primary monolayer cultures of winter flounder renal proximal-tubule cells were used to determine whether transepithelial transport could be protected from the damaging effects of extreme temperature by previous mild heat shock. Renal tubule epithelial cells were enzymatically dispersed and reorganized as confluent monolayer sheets on native rat tail collagen. Transepithelial electrical properties (potential difference, resistance, short-circuit current, and Na(+)-dependent glucose current) and unidirectional [35S]sulfate fluxes were measured in Ussing chambers at 22 degrees C. Examination of transepithelial electrical properties following acute 1-hr elevation of temperature over a range of 22-37 degrees C provided the basis for the "mild" versus "severe" thermal stress protocols. Severe elevation from 22 degrees C to 32 degrees C for 1.5 hr followed by 1.5 hr at 22 degrees C significantly decreased glucose current (7 +/- 0.7 to 3 +/- 0.8 microA/cm2) as well as net sulfate secretion [131 +/- 11 to 33 +/- 11 nmol/(cm2.hr)]. Mild heat shock of 27 degrees C for 6 hr prior to this severe heat shock completely protected both glucose transport (6 +/- 0.7 microA/cm2) and sulfate flux (149 +/- 13 nmol/(cm2.hr)]. Scanning electron microscopy showed that the number of microvilli on the apical (luminal) surface of the epithelium was decreased after a 32 degrees C heat shock. Monolayers exposed to 27 degrees C for 6 hr prior to incubation at 32 degrees C showed no loss of microvilli. SDS/PAGE analysis of protein patterns from the cultures showed that three classes of heat shock proteins were maximally induced at 27 degrees C. Inhibition of protein synthesis by cycloheximide prevented the thermoprotective effect of mild heat shock. This suggests that certain renal transport functions can be protected from sublethal but debilitating thermal stress by prior mild heat shock and that heat shock proteins may play a role in this protection.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barbe M. F., Tytell M., Gower D. J., Welch W. J. Hyperthermia protects against light damage in the rat retina. Science. 1988 Sep 30;241(4874):1817–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.3175623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyenbach K. W., Petzel D. H., Cliff W. H. Renal proximal tubule of flounder. I. Physiological properties. Am J Physiol. 1986 Apr;250(4 Pt 2):R608–R615. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.4.R608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon-Niermeijer E. K., Tuyl M., van de Scheur H. Evidence for two states of thermotolerance. Int J Hyperthermia. 1986 Jan-Mar;2(1):93–105. doi: 10.3109/02656738609019998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman K. G., Renfro J. L. Primary culture of flounder renal tubule cells: transepithelial transport. Am J Physiol. 1986 Sep;251(3 Pt 2):F424–F432. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.251.3.F424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami A., Schwartz J. H., Borkan S. C. Transient ischemia or heat stress induces a cytoprotectant protein in rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1991 Apr;260(4 Pt 2):F479–F485. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.4.F479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Renfro J. L. Control of phosphate transport in flounder renal proximal tubule primary cultures. Am J Physiol. 1989 Apr;256(4 Pt 2):R850–R857. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.4.R850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower L. E. Heat shock, stress proteins, chaperones, and proteotoxicity. Cell. 1991 Jul 26;66(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda N., Hishida A., Ikuma K., Yonemura K. Acquired resistance to acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1987 Jun;31(6):1233–1238. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes E. N., August J. T. Coprecipitation of heat shock proteins with a cell surface glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Apr;79(7):2305–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.7.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasiske B. L., O'Donnell M. P., Keane W. F. Direct effects of altered temperature on renal structure and function. Ren Physiol Biochem. 1988 Jan-Feb;11(1-2):80–88. doi: 10.1159/000173152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyasu S., Nishida E., Kadowaki T., Matsuzaki F., Iida K., Harada F., Kasuga M., Sakai H., Yahara I. Two mammalian heat shock proteins, HSP90 and HSP100, are actin-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(21):8054–8058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Rossi J., Petko L., Lindquist S. An ancient developmental induction: heat-shock proteins induced in sporulation and oogenesis. Science. 1986 Mar 7;231(4742):1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.3511530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaThangue N. B. A major heat-shock protein defined by a monoclonal antibody. EMBO J. 1984 Aug;3(8):1871–1879. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J., Chrétien P., Lambert H., Hickey E., Weber L. A. Heat shock resistance conferred by expression of the human HSP27 gene in rodent cells. J Cell Biol. 1989 Jul;109(1):7–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskey R. A., Mills A. D. Quantitative film detection of 3H and 14C in polyacrylamide gels by fluorography. Eur J Biochem. 1975 Aug 15;56(2):335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo A. Evidence for two states of thermotolerance in mammalian cells. Int J Hyperthermia. 1988 Sep-Oct;4(5):513–526. doi: 10.3109/02656738809027695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. S., Lui P. S., Tsai S. Heat induced ultrastructural injuries in lymphoid cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 1978 Dec;29(3):281–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(78)90071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. S., Wallach D. F., Tsai S. Temperature-induced variations in the surface topology of cultured lymphocytes are revealed by scanning electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Sep;70(9):2492–2496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.9.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron T., Vancompernolle K., Vandekerckhove J., Wilchek M., Geiger B. A 25-kD inhibitor of actin polymerization is a low molecular mass heat shock protein. J Cell Biol. 1991 Jul;114(2):255–261. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser D. D., Heikkila J. J., Bols N. C. Temperature ranges over which rainbow trout fibroblasts survive and synthesize heat-shock proteins. J Cell Physiol. 1986 Sep;128(3):432–440. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041280312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. Hsp70 accelerates the recovery of nucleolar morphology after heat shock. EMBO J. 1984 Dec 20;3(13):3095–3100. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen N. S., Mitchell H. K. Recovery of protein synthesis after heat shock: prior heat treatment affects the ability of cells to translate mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Mar;78(3):1708–1711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro J. L. Adaptability of marine teleost renal inorganic sulfate excretion: evidence for glucocorticoid involvement. Am J Physiol. 1989 Sep;257(3 Pt 2):R511–R516. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.3.R511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro J. L. Interdependence of Active Na+ and Cl- transport by the isolated urinary bladder of the teleost, Pseudopleuronectes americanus. J Exp Zool. 1977 Mar;199(3):383–390. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401990311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riabowol K. T., Mizzen L. A., Welch W. J. Heat shock is lethal to fibroblasts microinjected with antibodies against hsp70. Science. 1988 Oct 21;242(4877):433–436. doi: 10.1126/science.3175665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. A., Klein N. W., Hightower L. E., Edwards M. J. Heat shock and thermotolerance during early rat embryo development. Teratology. 1987 Oct;36(2):181–191. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420360205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Asai D. J., Lazarides E. The 68,000-dalton neurofilament-associated polypeptide is a component of nonneuronal cells and of skeletal myofibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Mar;77(3):1541–1545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J., Mizzen L. A. Characterization of the thermotolerant cell. II. Effects on the intracellular distribution of heat-shock protein 70, intermediate filaments, and small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complexes. J Cell Biol. 1988 Apr;106(4):1117–1130. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.4.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J., Suhan J. P. Morphological study of the mammalian stress response: characterization of changes in cytoplasmic organelles, cytoskeleton, and nucleoli, and appearance of intranuclear actin filaments in rat fibroblasts after heat-shock treatment. J Cell Biol. 1985 Oct;101(4):1198–1211. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]