Abstract

The pathophysiology of metabolic diseases such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, and obesity is complex and multifactorial. Developing new strategies to prevent or treat these diseases requires in vitro models with which researchers can extensively study the molecular mechanisms that lead to disease. Human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated derivatives have the potential to provide an unlimited source of disease-relevant cell types and, when combined with recent advances in genome editing, make the goal of generating functional metabolic disease models, for the first time, consistently attainable. However, this approach still has certain limitations including lack of robust differentiation methods and potential off-target effects. This review describes the current progress in human pluripotent stem cell-based metabolic disease research using genome-editing technology.

In the modern world, global health care faces many challenges. This is in large part due to the rising prevalence of common metabolic diseases, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (1). The pathophysiology of metabolic diseases is complex, whereas the underlying molecular mechanisms are only partially elucidated. In general, metabolic diseases are a consequence of the intersection of genetic and environmental factors (2). Great effort has been invested in identifying genetic variations that contribute to complex disease susceptibility. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and exome sequencing-based rare variants association studies (RVAS) have revealed a wealth of candidate genes and genomic loci associated with metabolic diseases (3–11). The challenge now is to pinpoint the causal variants or genes and unveil the molecular mechanism by which these genes affect pathophysiology.

Due to the lack of cells or tissues directly derived from patients, many in vivo/in vitro models have been employed for human metabolic disease studies. Among them, human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) hold great promise because they can be differentiated into any cell type in the human body, generating an unlimited source for in vitro disease studies. Also, the recent emergence of genome editing technology makes it possible to rapidly delineate the effects of genomic modification, allowing for further understanding of mechanistic insights of disease-associated loci. The combination of hPSCs, genome-editing technology, and genetic association studies will, in principle, provide a powerful platform to systematically model human metabolic disease in relevant cell types (eg, adipocyte, hepatocyte, and skeletal muscle cells, etc). Here we will focus on recent progress in using hPSCs and genome-editing technology to model metabolic diseases, including liver disease, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia.

Disease modeling with hPSCs

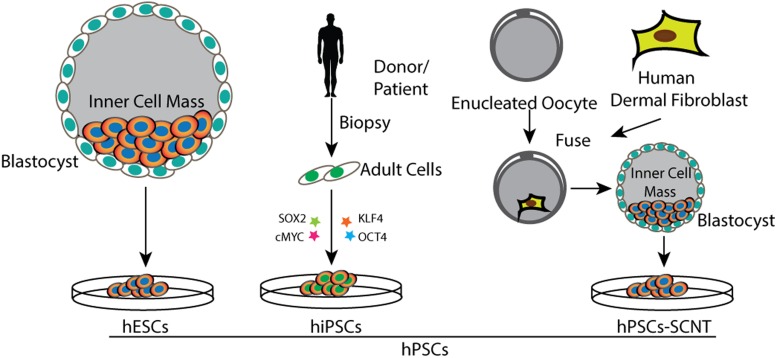

Mechanistic studies of human diseases have been impeded by the lack of specific types of cells or tissues for in vitro modeling. In vitro maintenance will often alter the phenotype of disease-affected cells that are otherwise adaptable to cell culture. hPSCs have the potential to generate any somatic cell type in the human body; thus, they have become an attractive source when primary cells are difficult to access for in vitro studies. hPSCs in our usage include three main types of cells: human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), which are directly derived from human embryos (12), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) reprogrammed from somatic cells via ectopic coexpression of transcription factors (13), and stem cells generated by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) (14) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of generation of three types of hPSCs: hESCs generated through isolation of inner cell mass from blastocyst; human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) generated through reprogramming of adult cells by exogenous expression of transcription factors; and hPSCs generated through SCNT (hPSCs-SCNT).

The isolation of the first hESCs accomplished by Thomson et al (12) gave rise to the idea of modeling human disease in a dish, which soon became firmly rooted in stem cell biology. Difficulties in targeting the genome of hESCs with homologous recombination (HR) have significantly limited the studies in hESCs. There were less than 20 genes that had been successfully modified in hESCs before the advent of genome editing technology (15). Disease modeling with hPSCs also requires robust differentiation of hPSCs into disease-relevant cells or tissues for metabolic disease studies. Although there are protocols allowing efficient differentiation into some cell types, most of them give rise to a mixture of diverse cell types, which significantly confounds reliable phenotypic interpretation (16). Given the ethical issues for generation of hESCs or hPSCs through SCNT, iPSCs have presented previously unanticipated opportunities for in vitro human disease modeling. Because iPSCs can be easily generated from a skin biopsy (17, 18) or blood sample (19, 20), they can be derived from healthy individuals or patients with certain diseases followed by differentiation into disease-relevant cells or tissues, permitting the comparison of phenotypic differences between patient-derived cells and control cells. Despite the strong promise of iPSCs, this type of disease-based modeling still has some limitations. Significant variability in biological properties among individual iPSC lines (21, 22) leads to different propensities to differentiate into certain disease-relevant cell types, complicating the task of articulating phenotypic characteristics. Here differences in genetic background are the major concern. Human genetic variation studies show that, on average, each person carries about 250–300 loss-of-function variants in protein-coding genes. Almost 100 of them have been previously implicated in inherited disorders (23, 24), with genetic variants leading to significant variations of gene expression among individuals (25). Therefore, the strategy that compares a few patient-derived iPSCs with healthy individuals poses significant risk for interpretation. This is particularly relevant for modeling metabolic diseases because a majority of them have a late onset with slow development of pathophysiological changes, manifesting subtly in vitro (1, 26, 27). In addition to genetic variants, the variability among iPSC lines can be attributed in part to differences in the epigenetic state (16, 28–30). A number of studies have documented that the epigenetic state can affect differentiation of iPSCs (31–33).

One strategy for modeling human diseases with hPSCs is through the generation of isogenic cell lines, which contain differences only in disease-causing mutations. They have the same genetic background, epigenetic state, and similar differentiation capacities. These similarities can substantially reduce variability among different lines and simplify analyses of interactions between genotype and phenotype. This in turn can lead to more reliable conclusions and better understanding of complex human diseases. The recent emergence of genome editing technologies makes this strategy possible by enabling robust modification of human genomic loci in hPSCs, ie, gene disruption, site mutation, and insertion (27, 34–37). A number of studies, including data from our laboratory, have demonstrated the advantages of using genome-editing technology for disease modeling in hPSCs (27, 37). As mentioned previously, progression of metabolic diseases is usually slow with very subtle phenotypic changes observed in in vitro studies. SORT1 (encoding Sortilin 1), which is highly associated with circulating level of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in GWAS (38), provides a cautionary tale. SORT1 is a risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) and regulates human blood LDL-C levels via the inhibition of hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion (39, 40). Studies found that when hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) are differentiated from hESCs, the disruption of the SORT1 gene through genome editing leads to approximately 65%–117% increase in VLDL secretion (27). Conversely, there is an almost 2-fold difference in the VLDL secretion by HLCs differentiated from two SORT1 wild-type hES cell lines derived from different people. This suggests that the phenotypic variation among lines might in some cases exert a larger effect than the phenotypic difference caused by particular disease mutations (27).

The promise of genome editing

The ability to modify targeted genomic loci holds enormous value for both basic and translational studies. Classical gene-modification methods relying on HR have been successfully applied in mouse embryonic stem cells. It has revolutionized gene function studies in mammals (41, 42), but it is still challenging in hPSCs (43), with only a few successful targeting cases reported since the derivation of the first hESCs (43–46). The promise of hPSC-based disease modeling was for a time dampened by the lack of high-efficiency gene-depletion or genome-modification methods. The solution lies in an emerging technology, called genome editing. Genome-editing techniques operate on the introduction of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) by programmable sequence-specific endonucleases to facilitate DNA damage repair by HR or nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). Genome-editing techniques enable efficient modification of targeted loci (site mutation, gene disruption, and insertion), therefore circumventing the shortfalls of hPSC research.

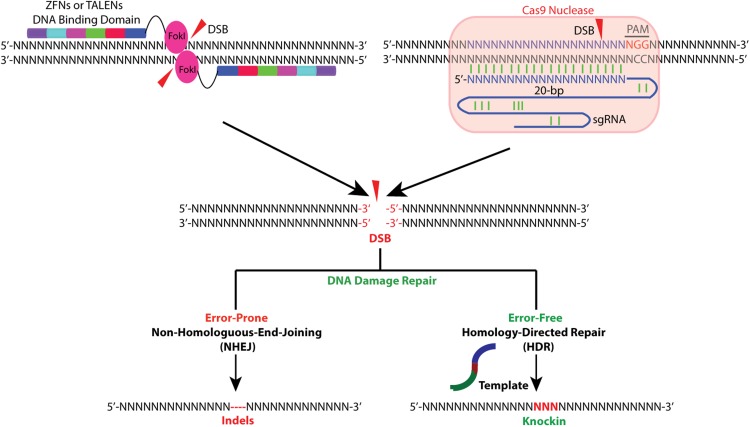

The three most widely used genome-editing technologies are zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) (34, 47–50), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) (51–53), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease (CRISPR/Cas) (54–57). ZFNs and TALENs rely on the generation of chimeric proteins consisting of an endonuclease catalytic domain and a DNA binding motif for inducing DSBs at the desired genomic loci. CRISPR/Cas technology uses a strategy in which Cas9 nuclease is guided to a specific genomic site by a small RNA through DNA base pairing (Figure 2). The key features including advantages and limitations of these three technologies are described below.

Figure 2.

Overview of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas-mediated gene targeting. ZFNs and TALENs, which usually function in pairs, are chimeric proteins consisting of endonuclease FokI catalytic domain and DNA binding motif as depicted at top left. Upon binding to targeting sites, nuclease domains of FokI dimerize and subsequently generate a DSB between the two binding sites. In the CRISPR/Cas system, Cas9 nuclease is recruited to targeting site by a sgRNA that recognizes and binds to a 20-bp DNA sequence in the presence of 5′-NGG motif (PAM, indicated in red). Upon binding, Cas9 mediates a DSB 3 bp upstream of the PAM (red triangle). Endonuclease-generated DSBs can be either repaired by NHEJ, which is error prone and usually leads to the introduction of indels, causing a gene knockout due to frameshift, or repaired by HDR in the presence of a homologous template, which can either be a sister chromosome or a DNA donor template introduced exogenously. HDR-mediated repair is usually used to knock in a site mutation or a tag.

Zinc finger nucleases

ZFNs are artificial restriction enzymes generated by fusing the nuclease domain of the bacterial FokI restriction enzyme to a DNA recognition domain. This domain consists of an array of site-specific zinc-finger DNA-binding motifs. Each binding motif is able to recognize three to four base pair DNA sequences. To bind to a longer genomic locus, multiple zinc finger motifs can be arranged in tandem. To cut the genomic site of interest, ZFNs are usually designed in pairs that recognize sequences flanking the targeting site. Upon binding of a ZFN pair, the FokI nuclease domains dimerize, activating their catalytic function and subsequently cutting the genomic DNA to generate a DSB (Figure 2). There are two main mechanisms in the cells responsible for DSBs repair: the error-prone NHEJ and the high-fidelity, homology-directed repair (HDR). Both can be used to achieve a desired editing outcome. When there is no repair template available, DSBs will be processed and religated through NHEJ, which introduces insertion or deletion (indel) mutations (Figure 2). This allows NHEJ to generate gene knockouts because indels occurring within coding exons can lead to frameshifts or premature truncations. HDR can be exploited to introduce precise, desired modifications in the presence of an exogenous repair template. This template contains the desired mutations flanked by homology arms (Figure 2). The exogenous repair template can be provided as either double-stranded DNA plasmids or single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides. The latter has been shown to have comparable genome-editing efficiency and accuracy in hESCs to double-stranded DNA donor plasmids, even with as few as 40 nucleotides of homology arm (34). Single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides provide a simple and effective strategy for making small edits in the genome, such as an introduction of a site mutation or insertion of small DNA fragments. The two caveats are that HDR, in contrast to NHEJ, is generally active only in dividing cells, and its efficiency varies widely upon different cell types and genomic loci (58).

ZFN technology has been successfully used to target several loci in hPSCs (34, 59, 60). Despite its advantages in genome editing, it is difficult for nonspecialists to harness its full potential. It is technically challenging to design or assemble multiple modular zinc finger motifs to achieve a high efficiency of genome editing. Commercial optimized ZFNs with high targeting efficiency can be purchased but are expensive compared with other genome-editing technologies (61). Also, the selection of genomic target sites is very limited. The freely available ZFN components can allow only the selecting of targeting sites every 200 bp in a random DNA sequence.

Transcription activator-like effector nucleases

TALENs are also artificial chimeric proteins. Here the FokI catalytic domain is fused to a different DNA binding domain composed of a new type of module derived from transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins (51, 52). TALEs were discovered in the plant pathogenic bacteria genus Xanthomonas. This genus contains DNA binding domains consisting of an array of 33–35 amino acid repeat motifs that each recognizes a single base pair. In each repeat motif, there are two adjacent hypervariable amino acids termed the repeat-variable diresidues. Repeat-variable diresidues confer specificity for one of the four DNA bases (53, 62). To target a specific genomic locus, 10–30 TALE repeat motifs are linked together and fused to the FokI catalytic domain, termed TALENs, to generate DSBs (Figure 2).

Compared with ZFNs, the single base recognizing feature of TALE motif offers greater design flexibility. This also leads to an increased technical challenge for the TALE arrays cloning due to extensive repeat sequences. Several strategies have been developed allowing efficient construction of TALE arrays (63–65). TALENs also have been demonstrated to present robust gene-editing efficacy in hPSCs (27, 66).

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease/Cas

The CRISPR/Cas system has most recently emerged as an alternative approach to ZFNs and TALENs. This system enables efficient genome editing with high precision (54–57). CRISPR/Cas is adapted from the bacterial adaptive immune system. This is where RNA-guided nucleases are used to cleave foreign DNA (67). Among the three types (I-III) of CRISPR systems discovered from a wide range of bacteria, type II is the one best articulated. CRISPR/Cas is comprised of the nuclease Cas9, CRISPR RNA (crRNA) array. It is derived from short segments of foreign DNA known as protospacers, and transactivating crRNA (tracrRNA) that facilitates the processing of crRNA array into discrete units (68, 69). The 20-nt short-guide RNA from each crRNA unit can then recognize a 20-bp DNA target in the presence of a 5′-protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) upstream of the RNA binding site. In current formulations of the CRISPR/Cas system, the tail portion of a single guide RNA will direct Cas9 to generate DSBs upon binding to the targeting loci (Figure 2). Thus, the CRISPR/Cas system can be used to target almost any genomic sequence in vicinity to the PAM motif by simply changing the crRNA. Significantly, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has been successfully reconstituted in mammalian cells by the coexpression of human codon-optimized Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 and by a chimeric, single-guide RNA (sgRNA) consisting of crRNA and tracrRNA (54). Cpf1 (CRISPR from Prevotella and Francisella 1) was recently discovered as a new CRISPR endonuclease (70). Unlike the well-characterized Cas9, Cpf1 generates a staggered DNA double-stranded break rather than a blunt end. This can facilitate NHEJ-based gene insertion. In addition, Cpf1 is recruited to a genomic site by a single RNA guide lacking tracrRNA, which could simplify the design and delivery of genome-editing tools. Among 16 Cpf1-family proteins tested, only two (from Acidominococcus and Lachnospiraceae) were found to mediate robust genome modification in mammalian cells (HEK293FT), yet genome editing capability has not been tested in hPSCs (70).

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been widely used to introduce genome modifications into cultured mammalian cells. Also, direct injection of sgRNA and mRNA encoding Cas9 into embryos has been demonstrated as an efficient way for generation of transgenic mice (71, 72). Comparing CRISPR/Cas and TALENs systems by targeting the same genomic loci in the same hPSC lines using the same delivery platform shows a much higher efficiency with the CRISPR/Cas system (73). This and other advantages over ZFNs and TALENs, including ease of use and capability of targeting multiple genomic sites with multiple sgRNAs simultaneously, the CRISPR/Cas system has facilitated hPSC-based disease modeling.

Genome editing and hPSC-based metabolic disease modeling

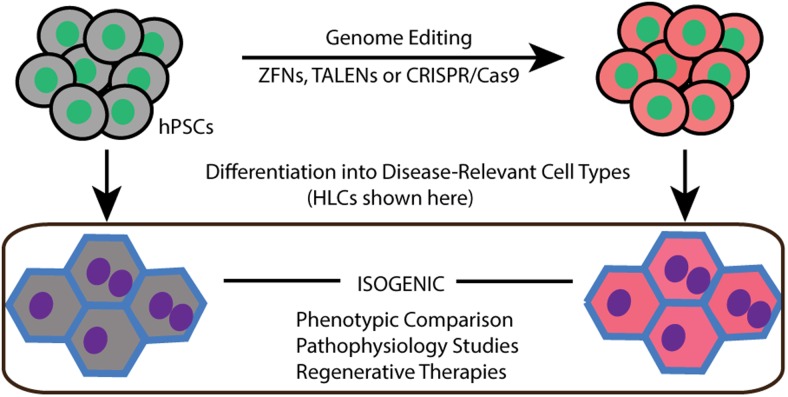

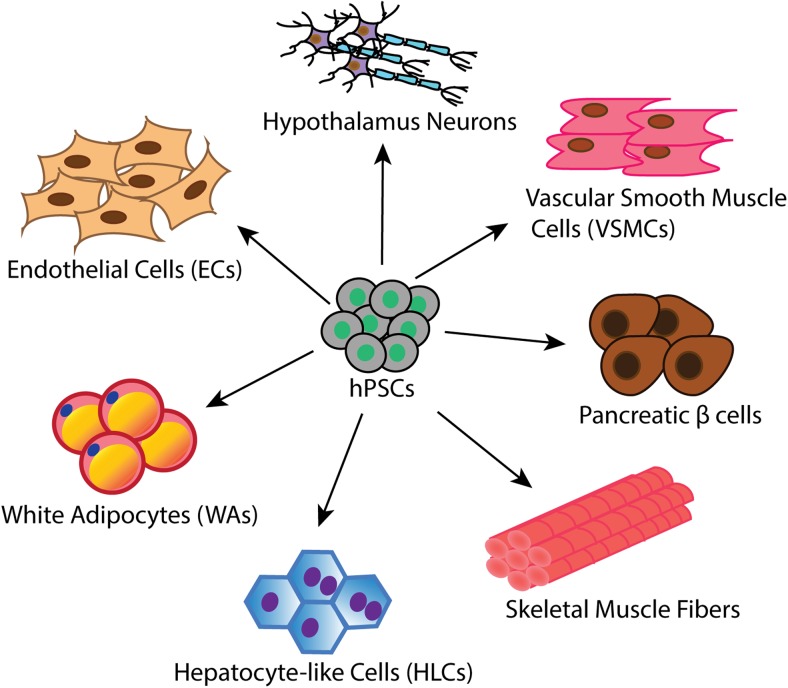

Genome-editing tools like ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas have been successfully applied to introduce genetic modifications in hPSCs (27, 34, 59, 60, 66, 73–80). Only a few studies have used genome editing tools to model human metabolic diseases by generating isogenic wild-type vs mutant cells lines (Table 1, Figure 3). The ability to differentiate hPSCs into metabolic disease-relevant cells including adipocytes, hepatocytes and skeletal muscle cells, etc is a key factor required for successful disease modeling. Here we will review the current differentiation protocols as well as the establishment of hPSC-based models with genome editing technologies (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Genome Editing-Based Metabolic Disease Modeling With hPSCs

| Cell Types | Differentiation Reference | Disease | Gene Targeted | Genome Editing Tool Applied | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White adipocytes | (84–87) | Insulin resistance | SORT1 | TALEN | (27) |

| AKT2 | TALEN | ||||

| Partial lipodystrophy | PLIN1 | TALEN | |||

| HLCs | (89–98) | A1AT deficiency | SERPINA1 | ZFN | (35) |

| TALEN | (100) | ||||

| Altered lipid traits | SORT1 | TALEN | (27) | ||

| Insulin resistance | AKT2 | TALEN | |||

| Skeletal muscle cells | (107–113) | DMD | Dystrophin | TALEN and CRISPR/Cas | (66) |

| VSMCs | (122) | Atherosclerosis | NA | NA | NA |

| ECs | (119–122) | Atherosclerosis | NA | NA | NA |

| Pancreatic β-cells | (115, 116) | T2D | NA | NA | NA |

| Hypothalamus neurons | (128) | Obesity |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Figure 3.

Experiment design for hPSC-based disease modeling. hPSCs are targeted by genome-editing tools, such as ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas, to generate isogenic cell lines. Then wild-type and mutated hPSCs are differentiated into disease-relevant cell types (HLCs are depicted here as an example) followed by phenotypic comparison and pathophysiological studies.

Figure 4.

Differentiation of hPSCs into various metabolic cell types, including white adipocytes (WAs), HLCs, skeletal muscle cells, pancreatic β-cells, VSMCs, ECs, and hypothalamic neurons.

hPSC-derived white and brown adipocytes

Adipocytes are essential regulators of whole-body energy homeostasis. In addition to their primary function of excess energy storage, white adipocytes also secrete many proteins that act as adipokines. Adipokines regulate a large range of processes in the human body such as energy balance, immune function, and blood pressure (81). The worldwide prevalence of obesity poses a major public health problem by increasing individual risk for developing metabolic syndromes including T2D, CAD, and NAFLD, etc. What remains unclear, are the molecular underpinnings of obesity. Brown adipocytes burn energy in lipids or glucose to produce heat through nonshivering thermogenesis, revealing great therapeutic potential against obesity (82, 83). Because many metabolic diseases are associated with the dysfunction of adipocytes, studies of adipocyte-related diseases will provide important insights into the understanding of metabolic diseases.

To date, there are many established protocols from different groups for white adipocyte differentiation from hPSCs (84–87), whereas only one for brown adipocyte differentiation (87). Protocols developed by Ahfeldt et al in our laboratory rely on the overexpression of transcription factor peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ2 for white adipocytes and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta and/or PR domain containing 16 for brown adipocyte differentiation. This protocol results in 90% of hPSCs differentiating into white adipocytes (87). Further characterization of the hPSCs differentiated white adipocytes show that they have a similar transcriptional signature to primary adipocytes. Most importantly, both hPSCs-derived white and brown adipocytes exhibit mature functional properties, such as lipolysis, adiponectin secretion, de novo fatty acid synthesis, intact insulin signaling, and glucose uptake.

By using TALENs, Ding et al (27) reported a pioneering work of metabolic disease modeling in hPSCs. They introduced genomic alterations including knockout mutations, knock-in missense mutations, and functional frameshift mutations to genome sites of 15 genes that are involved in lipid metabolism, insulin signaling, and glucose metabolism. Following this strategy, they found that SORT1 (encoding sortilin) plays an important role in regulating glucose uptake in response to insulin in hPSCs differentiated adipocytes. This suggests its potential function in insulin sensitivity in humans. Through the systematic study of AKT2 and a gain-of-function mutant (E17K) discovered in patients with severe hypoglycemia, hypoinsulinemia, and increased body fat, they found markedly increased triglyceride accumulation in AKT2 (E17K) mutant white adipocytes. Another interesting finding was that the secretion level of inflammatory adipokines, such as IL-18 (IL-8), monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 were significantly higher in AKT2 (E17K) adipocytes than AKT2 knockout or wild-type adipocytes. Partial lipodystrophy caused by a frameshift mutation in PLIN1 was also modeled in the differentiated adipocytes, showing that the mutated PLIN1 had significantly enhanced lipolysis. Overall, this study provides a proof of principle for metabolic disease modeling in hPSCs for the utility of genome editing technology as well as the importance of hPSC-derived adipocytes for metabolic studies.

hPSC-derived HLCs

The liver plays a key role in the metabolism of the human body with numerous functions, such as detoxification, lipid metabolism, regulation of glycogen storage, and hormone production (88). Many metabolic diseases are associated with hepatic dysfunction. Due to the difficulty in accessing human primary hepatocytes, alternative human HLCs are in great need both in clinical and research settings, providing a platform for drug toxicity tests and facilitating studies of metabolic diseases. Hepatoma cells and immortalized hepatocytes are widely used as alternatives for in vitro studies, but the greatest concern is that those cells are not able to reliably reflect the physiology of primary hepatocytes. Recent advances in differentiation of hPSCs into HLCs provide a reliable and inexhaustible source of human hepatocytes for liver disease studies (88). There are a number of HLC differentiation protocols developed by different groups (89–97). These aim to replay key stages of liver development including definitive endoderm, hepatic endoderm, hepatoblasts, and HLCs (96). Unfortunately, most of these differentiation protocols lead to large variations in differentiation efficiencies among lines. Takayama et al (97, 98) have reported that the passaging of hepatoblasts on laminin-111-coated surface allows α-fetoprotein-positive cells to overtake α-fetoprotein-negative cells. This resulted in a purer population of hepatocytes, with the variability of differentiation capacities between lines significantly reduced.

HLCs derived from hPSCs have been widely used to model liver diseases. Most studies focus on the comparison of iPSCs derived from patients to those from healthy individuals. α1-antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency was the first heritable hepatic metabolic disease modeled with HLCs (99). Specific mutations of the A1AT-encoding gene SERPINA1 lead to accumulation of misfolded A1AT polymers in hepatocytes, resulting in hepatotoxicity and liver disease. A1AT polymers were entrapped in the endoplasmic reticulum of HLCs derived from patients with A1AT deficiency but not healthy individuals. This phenocopies an important feature of the disease and provides the first proof of principle for HLC-based liver disease modeling. Later the same group corrected the SERPINA1 mutation in patient-derived iPSCs by using the genome editing tool ZFNs in combination with the PiggyBAC transposon system. This led to the successful rescue of the disease phenotype (35). TALENs were also used to rescue the disease phenotype by correcting the SERPINA1 mutation in iPSCs derived from patients (100).

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is caused by the mutation of the gene encoding low-density lipoprotein receptor. FH was modeled in iPSCs derived from patients and healthy donors (99, 101), showing that HLCs from patients exhibit significantly reduced uptake of low-density lipoprotein compared with control cells, as expected. Furthermore, low-density lipoprotein receptor was found to regulate VLDL secretion, with up to an 8-fold increase of secreted VLDL in HLCs derived from patients compared with control cells. The indication is that the elevated circulating LDL-C in patients with FH might be a consequence of both reduced hepatic LDL-C uptake and increased VLDL secretion (101).

Patient-derived HLCs were also used to model glycogen storage disease type 1a (GSD1a), which is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations on the gene encoding glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit (G6PC) (102), a key protein for both gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Deficiency of G6PC leads to complex metabolic disorders including hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, hypertriglyceridemia, and hyperuricemia (102, 103). GSD1a-patients have enlarged liver and kidneys due to the increased storage of glycogen and lipids. In the iPSCs-based GSD1a model, HLCs derived from patients accumulate more glycogen and triglycerides than the control cells, consistent with the phenotypes of G6PC deficiency (99).

In addition to the function of SORT1 discovered in hPSCs-differentiated adipocytes, knockout of SORT1 was shown to inhibit hepatic VLDL secretion in HLCs. This is consistent with animal models of SORT1 function, in which the inhibition of hepatic VLDL secretion led to lower circulating cholesterol levels in blood as well as a reduced risk of CAD (27). In the same study, insulin resistance was also modeled in HLCs by knocking out AKT2 or knocking-in AKT2 (E17K), a gain-of-function mutant of AKT2. The results showed that glucose production is significantly lower in AKT2 (E17K) HLCs and higher in AKT2 knockout HLCs compared with wild-type cells, as expected. In summary, these studies demonstrate that HLCs accurately phenocopy the glucose and lipid metabolic phenotypes of human disease, making them a useful system for modeling complex liver metabolic disorders.

hPSC-derived skeletal muscle cells

Skeletal muscles play critical roles in glucose homeostasis and whole-body protein metabolism (104, 105). The development of insulin resistance in muscle marks the onset of type 2 diabetes (106). There are also a group of muscle diseases characterized by progressive muscle weakness and muscle protein defects called muscular dystrophy (MD). Among them, Duchenne MD (DMD) is the most common childhood form of MD. DMD is a severe muscular degenerative disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in the gene DMD coding for the protein dystrophin, which provides structural stability to the cell membrane. A recent study reported efficient and precise correction of DMD gene mutations in patient-derived iPSCs using TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 (66). After differentiation of the corrected iPSCs into skeletal muscle cells based on a previously established protocol (107), functional dystrophin protein was successfully restored. This shows great promise of genome editing tools for developing hPSC-based gene therapy. A number of protocols for the differentiation of hPSCs into skeletal muscle cells have been developed (107–112). Many of them rely on overexpression of transcription factors such as paired box transcription factor-7, Myogenic Differentiation 1, and paired box transcription factor-3, which are not suitable for regenerative therapy. Recently an exogenous DNA-free and serum-free protocol has been established by recapitulating early stages of muscle lineage development in vivo (113). Contractile fibers were generated from hPSCs, providing a powerful platform for in vitro studies of skeletal muscle-related diseases.

hPSC-derived pancreatic β-cells

Pancreatic β-cells play an essential role in metabolic homeostasis by coupling ambient glucose levels with insulin secretion (114). Dysfunction of β-cells, normally found in type 1 diabetes or T2D, leads to hyperglycemia, with severe complications over time. Human genetic studies have proven a powerful tool to understand the molecular mechanism of β-cell dysfunction. GWAS and RVAS studies have successfully identified many susceptibility variants associated with the dysfunction of β-cells. Also, the progress of functional studies of the genes has been hampered by the lack of human model systems. Recently two groups have established methods to make insulin-producing cells from hPSCs that share significant functional features with human β-cells (115, 116). The development of robust differentiation strategy would provide an unlimited source of cells for both regenerative therapies and disease modeling. The combination of hPSC-derived β-cells and genome-editing technology will allow systematic study of the molecular function of the susceptibility genes, providing detailed insights into the pathophysiology of diabetes.

hPSC-derived endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells

Blood vessels consist of two main cellular components: endothelial cells (ECs) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Both ECs and VSMCs regulate a wide range of vascular activities, such as vascular tone, nutrient uptake, and inflammatory responses (117). Dysfunction of ECs and VSMCs is associated with many pathophysiological conditions, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and diabetes (118). Various methods have been reported to differentiate hPSCs into ECs and VSMCs (119–122), but the protocols developed by Patsch et al (122) represent several advantages over the others with chemically defined medium and rapid differentiation with high efficiency, the most valuable aspect being that the differentiated ECs and VSMCs can be purified to near homogeneity after magnetic-associated cell sorting.

hPSC-derived hypothalamic neuron

Recent advances in GWAS have identified 97 genomic loci associated with obesity, with further gene expression analyses providing strong support for a role of the central nervous system in obesity susceptibility (3). It is suggested that the expression of many obesity-associated genes is enriched in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, which are key sites of appetite regulation, but even more strongly enriched in the hippocampus and limbic system, which regulate emotion, memory and learning.

The hypothalamus plays a central role in regulating whole-body energy homeostasis by controlling food intake, body temperature, and energy expenditure, etc (123). Mutations in genes including POMC (124), MC4R (125), LEP (126), and LEPR (127), which are involved in leptin-melanocortin signaling in the hypothalamus, result in severe obesity in both humans and rodents, confirming the critical role of the hypothalamus in regulation of energy homeostasis. The function of most of GWAS-discovered susceptibility genes enriched in the hypothalamus has not been articulated yet due to the difficulty in accessing neuronal cells. The first protocol for hypothalamus neuron differentiation from hPSCs was reported early this year (128). The 45-day differentiation protocol mimics in vivo hypothalamic neuron development and gives rise to a high percentage of mature neurons expressing POMC and neuropeptide Y (NPY). This unlimited source of hypothalamic-like neurons together with genome-editing tools will allow researchers to systematically study the molecular function of obesity susceptibility genes identified from GWAS, thereby understanding the pathophysiology of obesity.

Shortcomings of genome editing-based hPSC disease models

Although recent advances in genome-editing technology dramatically accelerate hPSC-based in vitro disease modeling by allowing rapid and efficient introduction of targeted alterations to the genomic loci, the issues of off-target effects remain a pressing concern.

By using ZFNs to target a genomic locus in hPSCs, Dirk et al (60) studied off-target effects by first identifying the most likely off-target sites in the whole genome. This was based on sequence similarity to the on-target site, followed by identification of NHEJ-mediated alterations in those predicted sites (60). Among 46 predicted off-target loci, only one event was identified in one of four clones tested, indicating a rather low frequency of off-targets with ZFNs. Consistent with this conclusion, two unbiased genome-wide studies performed in a human tumor cell line also revealed a low rate of off-target events using ZFNs (129, 130). Application of TALENs in hPSCs also revealed a low rate of off-targeting events via whole-genome sequencing (74, 131, 132). CRISPR/Cas has a low frequency of off-target effects in human cells in a number of studies (131–133), whereas others have found the opposite to be true (134–136).

Even though low-rate off-target effects were reported by most studies using ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas systems, there could still be potential off-targets, thus confounding the phenotypic comparison between wild-type and targeted cells. Given the low frequency of off-target effects, it is highly unlikely that multiple genome-edited clones have the same off-targets. To ensure that the phenotypic differences are truly related to the on-target site of interest, a more rigorous experimental design for hPSC-based disease modeling should be applied. Phenotypic differences would be compared between multiple wild-type and multiple targeted lines. Ideally, rescue experiments should also be included.

Concluding remarks

Human genetic studies from GWAS and exome sequencing-based RVAS have identified many susceptibility genomic loci or genes related to different metabolic diseases including obesity (3), T2D (4, 137), CAD (138), and NAFLD (139) and altered circulating lipid levels (8). The molecular function of most of these candidate genes remains unknown. The recent advances in genome-editing technology allows rapid and efficient targeting of any desired genomic locus in hPSCs. Combined with the establishment of robust protocols to differentiate hPSCs into metabolically active cells or tissues, these advances provide an effective and valuable platform to systematically study the molecular function of candidate genes. Although the combination of genome editing tools and hPSCs have provided previously unforeseen possibilities to model human metabolic diseases in the culture dish, this approach still faces numerous obstacles. For example, some differentiation protocols are far from ideal, leading to varied differentiation efficiencies or immature cells. This can obscure the phenotypic comparison between wild-type and mutated cells, especially problematic in studying disease-causal genes with subtle effects. Given the fact that most the metabolic diseases are complex and late onset, the phenotypic changes caused by a single gene defect might not be noticeable. Improvement of the differentiation method is of the utmost importance to achieve accurate hPSC-based disease modeling. Furthermore, for some cells, particularly neurons, the ability to phenocopy the human disease relies on their interaction with other types of cells or correct neuronal networks; therefore, it might be challenging to model the disease in such a single-cell type setup, and more advanced coculture systems involving different cell types should be developed for such studies. Very importantly, potential off-target effects of the genome-editing tools need to be addressed, with more stringent experimental design to overcome this hurdle.

In summary, the use of genome editing to model human diseases is rapidly becoming a standard strategy in biomedical research. Combined with hPSCs and genome-wide studies, it will dramatically expand our understanding of the pathophysiology of metabolic disorders and, hopefully within the foreseeable future, the development of novel therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21HL120781, R01DK097768, and U01HL107440.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- A1AT

- α1-antitrypsin

- CAD

- coronary artery disease

- CRISPR/Cas

- clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease

- crRNA

- CRISPR RNA

- DMD

- Duchenne MD

- DSB

- double-strand break

- EC

- endothelial cell

- FH

- familial hypercholesterolemia

- G6PC

- glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit

- GSD1a

- glycogen storage disease type 1a

- GWAS

- genome-wide association studies

- HDR

- homology-directed repair

- hESC

- human embryonic stem cell

- HLC

- hepatocyte-like cell

- hPSC

- human pluripotent stem cell

- HR

- homologous recombination

- indel

- insertion or deletion

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- LDL-C

- low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- MD

- muscular dystrophy

- NAFLD

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NHEJ

- nonhomologous end joining

- PAM

- 5′-protospacer adjacent motif

- RVAS

- exome sequencing-based rare variant association studies

- SCNT

- somatic cell nuclear transfer

- sgRNA

- single-guide RNA

- SORT1

- sortilin1

- TALE

- transcription activator-like effector

- TALEN

- transcription activator-like effector nuclease

- T2D

- type 2 diabetes

- tracrRNA

- transactivating crRNA

- VLDL

- very low-density lipoprotein

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

- ZFN

- zinc-finger nuclease.

References

- 1. Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:943162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2. Sale MM, Woods J, Freedman BI. Genetic determinants of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2006;8(1):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42(7):579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium, Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network Type 2 Diabetes (AGEN-T2D) Consortium, South Asian Type 2 Diabetes (SAT2D) Consortium, et al. Genome-wide trans-ancestry meta-analysis provides insight into the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1121–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Global Lipids Genetics C, Willer CJ, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1274–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466(7307):707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Surakka I, Horikoshi M, Magi R, et al. The impact of low-frequency and rare variants on lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2015;47(6):589–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Speliotes EK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Wu J, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(3):e1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tachibana M, Amato P, Sparman M, et al. Human embryonic stem cells derived by somatic cell nuclear transfer. Cell. 2013;153(6):1228–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saha K, Jaenisch R. Technical challenges in using human induced pluripotent stem cells to model disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(6):584–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soldner F, Jaenisch R. Medicine. iPSC disease modeling. Science. 2012;338(6111):1155–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321(5893):1218–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134(5):877–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seki T, Yuasa S, Oda M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(1):11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loh YH, Hartung O, Li H, et al. Reprogramming of T cells from human peripheral blood. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(1):15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boulting GL, Kiskinis E, Croft GF, et al. A functionally characterized test set of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(3):279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bock C, Kiskinis E, Verstappen G, et al. Reference maps of human ES and iPS cell variation enable high-throughput characterization of pluripotent cell lines. Cell. 2011;144(3):439–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis GR, Auton A, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491(7422):56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Majewski J, Pastinen T. The study of eQTL variations by RNA-seq: from SNPs to phenotypes. Trends Genet. 2011;27(2):72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Travers ME, McCarthy MI. Type 2 diabetes and obesity: genomics and the clinic. Hum Genet. 2011;130(1):41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ding Q, Lee YK, Schaefer EA, et al. A TALEN genome-editing system for generating human stem cell-based disease models. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(2):238–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471(7336):68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy. Nature. 2012;481(7381):295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Unternaehrer JJ, Daley GQ. Induced pluripotent stem cells for modelling human diseases. Philosoph Transact R Soc London Series B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1575):2274–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim K, Zhao R, Doi A, et al. Donor cell type can influence the epigenome and differentiation potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(12):1117–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Polo JM, Liu S, Figueroa ME, et al. Cell type of origin influences the molecular and functional properties of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(8):848–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nazor KL, Altun G, Lynch C, et al. Recurrent variations in DNA methylation in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated derivatives. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(5):620–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soldner F, Laganiere J, Cheng AW, et al. Generation of isogenic pluripotent stem cells differing exclusively at two early onset Parkinson point mutations. Cell. 2011;146(2):318–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yusa K, Rashid ST, Strick-Marchand H, et al. Targeted gene correction of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;478(7369):391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sebastiano V, Maeder ML, Angstman JF, et al. In situ genetic correction of the Sickle cell anemia mutation in human induced pluripotent stem cells using engineered zinc finger nucleases. Stem Cells. 2011;29(11):1717–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reinhardt P, Schmid B, Burbulla LF, et al. Genetic correction of a LRRK2 mutation in human iPSCs links parkinsonian neurodegeneration to ERK-dependent changes in gene expression. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(3):354–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, et al. Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Musunuru K, Strong A, Frank-Kamenetsky M, et al. From noncoding variant to phenotype via SORT1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466(7307):714–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strong A, Ding Q, Edmondson AC, et al. Hepatic sortilin regulates both apolipoprotein B secretion and LDL catabolism. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2807–2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smithies O, Gregg RG, Boggs SS, Koralewski MA, Kucherlapati RS. Insertion of DNA sequences into the human chromosomal beta-globin locus by homologous recombination. Nature. 1985;317(6034):230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell. 1987;51(3):503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zwaka TP, Thomson JA. Homologous recombination in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(3):319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Costa M, Dottori M, Sourris K, et al. A method for genetic modification of human embryonic stem cells using electroporation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(4):792–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davis RP, Ng ES, Costa M, et al. Targeting a GFP reporter gene to the MIXL1 locus of human embryonic stem cells identifies human primitive streak-like cells and enables isolation of primitive hematopoietic precursors. Blood. 2008;111(4):1876–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Irion S, Luche H, Gadue P, Fehling HJ, Kennedy M, Keller G. Identification and targeting of the ROSA26 locus in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):1477–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Porteus MH, Baltimore D. Chimeric nucleases stimulate gene targeting in human cells. Science. 2003;300(5620):763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Miller JC, Holmes MC, Wang J, et al. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(7):778–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sander JD, Dahlborg EJ, Goodwin MJ, et al. Selection-free zinc-finger-nuclease engineering by context-dependent assembly (CoDA). Nat Methods. 2011;8(1):67–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wood AJ, Lo TW, Zeitler B, et al. Targeted genome editing across species using ZFNs and TALENs. Science. 2011;333(6040):307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, et al. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science. 2009;326(5959):1509–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moscou MJ, Bogdanove AJ. A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science. 2009;326(5959):1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Deng D, Yan C, Pan X, et al. Structural basis for sequence-specific recognition of DNA by TAL effectors. Science. 2012;335(6069):720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339(6121):823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jinek M, East A, Cheng A, Lin S, Ma E, Doudna J. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. eLife. 2013;2:e00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saleh-Gohari N, Helleday T. Conservative homologous recombination preferentially repairs DNA double-strand breaks in the S phase of the cell cycle in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(12):3683–3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, et al. Gene targeting of a disease-related gene in human induced pluripotent stem and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):97–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(9):851–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ramirez CL, Foley JE, Wright DA, et al. Unexpected failure rates for modular assembly of engineered zinc fingers. Nat Methods. 2008;5(5):374–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mak AN, Bradley P, Cernadas RA, Bogdanove AJ, Stoddard BL. The crystal structure of TAL effector PthXo1 bound to its DNA target. Science. 2012;335(6069):716–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(12):e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reyon D, Tsai SQ, Khayter C, Foden JA, Sander JD, Joung JK. FLASH assembly of TALENs for high-throughput genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(5):460–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schmid-Burgk JL, Schmidt T, Kaiser V, Honing K, Hornung V. A ligation-independent cloning technique for high-throughput assembly of transcription activator-like effector genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li HL, Fujimoto N, Sasakawa N, et al. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(1):143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482(7385):331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Garneau JE, Dupuis ME, Villion M, et al. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 2010;468(7320):67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(39):E2579–E2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, et al. Cpf1 Is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163(3):759–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153(4):910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shen B, Zhang J, Wu H, et al. Generation of gene-modified mice via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting. Cell Res. 2013;23(5):720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ding Q, Regan SN, Xia Y, Oostrom LA, Cowan CA, Musunuru K. Enhanced efficiency of human pluripotent stem cell genome editing through replacing TALENs with CRISPRs. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(4):393–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hockemeyer D, Wang H, Kiani S, et al. Genetic engineering of human pluripotent cells using TALE nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(8):731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhu Z, Verma N, Gonzalez F, Shi ZD, Huangfu D. A CRISPR/Cas-mediated selection-free knockin strategy in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(6):1103–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Merkle FT, Neuhausser WM, Santos D, et al. Efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated generation of knockin human pluripotent stem cells lacking undesired mutations at the targeted locus. Cell Rep. 2015;11(6):875–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gonzalez F, Zhu Z, Shi ZD, et al. An iCRISPR platform for rapid, multiplexable, and inducible genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(2):215–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Peters DT, Cowan CA, Musunuru K. Genome Editing in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cambridge, MA: StemBook; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yu C, Liu Y, Ma T, et al. Small molecules enhance CRISPR genome editing in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(2):142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chen Y, Cao J, Xiong M, et al. Engineering human stem cell lines with inducible gene knockout using CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(2):233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lau DC, Dhillon B, Yan H, Szmitko PE, Verma S. Adipokines: molecular links between obesity and atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(5):H2031–H2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Moisan A, Lee YK, Zhang JD, et al. White-to-brown metabolic conversion of human adipocytes by JAK inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(1):57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xiong C, Xie CQ, Zhang L, et al. Derivation of adipocytes from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(6):671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. van Harmelen V, Astrom G, Stromberg A, et al. Differential lipolytic regulation in human embryonic stem cell-derived adipocytes. Obesity. 2007;15(4):846–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hannan NR, Wolvetang EJ. Adipocyte differentiation in human embryonic stem cells transduced with Oct4 shRNA lentivirus. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18(4):653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ahfeldt T, Schinzel RT, Lee YK, et al. Programming human pluripotent stem cells into white and brown adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(2):209–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Dianat N, Steichen C, Vallier L, Weber A, Dubart-Kupperschmitt A. Human pluripotent stem cells for modelling human liver diseases and cell therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2013;13(2):120–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lavon N, Yanuka O, Benvenisty N. Differentiation and isolation of hepatic-like cells from human embryonic stem cells. Differentiation. 2004;72(5):230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Schwartz RE, Linehan JL, Painschab MS, Hu WS, Verfaillie CM, Kaufman DS. Defined conditions for development of functional hepatic cells from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(6):643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Duan Y, Catana A, Meng Y, et al. Differentiation and enrichment of hepatocyte-like cells from human embryonic stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells. 2007;25(12):3058–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cai J, Zhao Y, Liu Y, et al. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into functional hepatic cells. Hepatology. 2007;45(5):1229–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hay DC, Fletcher J, Payne C, et al. Highly efficient differentiation of hESCs to functional hepatic endoderm requires Activin A and Wnt3a signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(34):12301–12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Basma H, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yannam GR, et al. Differentiation and transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(3):990–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Brolen G, Sivertsson L, Bjorquist P, et al. Hepatocyte-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells specifically via definitive endoderm and a progenitor stage. J Biotechnol. 2010;145(3):284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Takayama K, Nagamoto Y, Mimura N, et al. Long-term self-renewal of human ES/iPS-derived hepatoblast-like cells on human laminin 111-coated dishes. Stem Cell Rep. 2013;1(4):322–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Takayama K, Morisaki Y, Kuno S, et al. Prediction of interindividual differences in hepatic functions and drug sensitivity by using human iPS-derived hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(47):16772–16777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3127–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Choi SM, Kim Y, Shim JS, et al. Efficient drug screening and gene correction for treating liver disease using patient-specific stem cells. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2458–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Cayo MA, Cai J, DeLaForest A, et al. JD induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes faithfully recapitulate the pathophysiology of familial hypercholesterolemia. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2163–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chou JY. The molecular basis of type 1 glycogen storage diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1(1):25–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Burchell A. The molecular basis of the type 1 glycogen storage diseases. BioEssays. 1992;14(6):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Levine TB, Levine AB. Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2006;ix:488. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hoppeler H, Fluck M. Normal mammalian skeletal muscle and its phenotypic plasticity. J Exp Biol. 2002;205(Pt 15):2143–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Wolfe RR. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(3):475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Tanaka A, Woltjen K, Miyake K, et al. Efficient and reproducible myogenic differentiation from human iPS cells: prospects for modeling Miyoshi myopathy in vitro. PloS One. 2013;8(4):e61540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Darabi R, Arpke RW, Irion S, et al. Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore DYSTROPHIN and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(5):610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Darabi R, Gehlbach K, Bachoo RM, et al. Functional skeletal muscle regeneration from differentiating embryonic stem cells. Nat Med. 2008;14(2):134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Albini S, Coutinho P, Malecova B, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming of human embryonic stem cells into skeletal muscle cells and generation of contractile myospheres. Cell Rep. 2013;3(3):661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Salani S, Donadoni C, Rizzo F, Bresolin N, Comi GP, Corti S. Generation of skeletal muscle cells from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells as an in vitro model and for therapy of muscular dystrophies. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(7):1353–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Abujarour R, Bennett M, Valamehr B, et al. Myogenic differentiation of muscular dystrophy-specific induced pluripotent stem cells for use in drug discovery. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(2):149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Chal J, Oginuma M, Al Tanoury Z, et al. Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to muscle fiber to model Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(9):962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Thomsen SK, Gloyn AL. The pancreatic β cell: recent insights from human genetics. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25(8):425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Rezania A, Bruin JE, Arora P, et al. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(11):1121–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gurtler M, et al. Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159(2):428–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ganz P, Hsue PY. Endothelial dysfunction in coronary heart disease is more than a systemic process. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(27):2025–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sena CM, Pereira AM, Seica R. Endothelial dysfunction—a major mediator of diabetic vascular disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(12):2216–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. James D, Nam HS, Seandel M, et al. Expansion and maintenance of human embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells by TGFβ inhibition is Id1 dependent. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(2):161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Kane NM, Meloni M, Spencer HL, et al. Derivation of endothelial cells from human embryonic stem cells by directed differentiation: analysis of microRNA and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(7):1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Orlova VV, Drabsch Y, Freund C, et al. Functionality of endothelial cells and pericytes from human pluripotent stem cells demonstrated in cultured vascular plexus and zebrafish xenografts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(1):177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Patsch C, Challet-Meylan L, Thoma EC, et al. Generation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(8):994–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Pearson CA, Placzek M. Development of the medial hypothalamus: forming a functional hypothalamic-neurohypophyseal interface. Curr Topics Dev Biol. 2013;106:49–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Krude H, Biebermann H, Luck W, Horn R, Brabant G, Gruters A. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat Genet. 1998;19(2):155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Farooqi IS, Keogh JM, Yeo GS, Lank EJ, Cheetham T, O'Rahilly S. Clinical spectrum of obesity and mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1085–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature. 1997;387(6636):903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Farooqi IS, Wangensteen T, Collins S, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of congenital deficiency of the leptin receptor. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(3):237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Wang L, Meece K, Williams DJ, et al. Differentiation of hypothalamic-like neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Gabriel R, Lombardo A, Arens A, et al. An unbiased genome-wide analysis of zinc-finger nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(9):816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Pattanayak V, Ramirez CL, Joung JK, Liu DR. Revealing off-target cleavage specificities of zinc-finger nucleases by in vitro selection. Nat Methods. 2011;8(9):765–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Veres A, Gosis BS, Ding Q, et al. Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(1):27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Smith C, Gore A, Yan W, et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN-based genome editing in human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(1):12–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Suzuki K, Yu C, Qu J, et al. Targeted gene correction minimally impacts whole-genome mutational load in human-disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cell clones. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(1):31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):822–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Lin Y, Cradick TJ, Brown MT, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(11):7473–7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Ali O. Genetics of type 2 diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2013;4(4):114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Lee JY, Lee BS, Shin DJ, et al. A genome-wide association study of a coronary artery disease risk variant. J Hum Genet. 2013;58(3):120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Chalasani N, Guo X, Loomba R, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with histologic features of nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1567–1576.e1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]