Abstract

Trauma exposure and smoking co-occur at an alarmingly high rate. However, there is little understanding of the mechanisms underlying this clinically significant relation. The present study examined perceived stress as an explanatory mechanism linking posttraumatic stress symptom severity and smoking-specific avoidance/inflexibility, perceived barriers to smoking cessation, and negative affect reduction/negative reinforcement expectancies from smoking among trauma-exposed smokers. Participants were trauma-exposed, treatment-seeking daily cigarette smokers (n = 179; 48.0% female; Mage = 41.17; SD = 12.55). Results indicated that posttraumatic stress symptom severity had an indirect significant effect on each of the dependent variables via perceived stress. The present results provide empirical support that perceived stress may be an underlying mechanism that indirectly explains posttraumatic symptoms relation to smoking-specific avoidance/inflexibility, perceived barriers to smoking cessation, and negative affect reduction/negative reinforcement expectancies among trauma-exposed smokers. These findings suggest that there may be clinical utility in targeting perceived stress among trauma-exposed smokers via stress management psychoeducation and skills training.

Keywords: Posttraumatic Stress, Perceived Stress, Tobacco, Trauma, Smoking

Trauma exposure is alarmingly high among the general population, with more than half of individuals reporting exposure to a DSM-defined traumatic event (Spitzer et al., 2009). Trauma-exposed persons (with or without post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) are more likely to be smokers, have higher levels of nicotine dependence, and have poorer outcomes during quit attempts than non-trauma exposed persons (Feldner et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2008). Despite the documented co-occurrence and clinically-significant relations between trauma exposure and smoking, the mechanisms by which posttraumatic stress symptom severity contributes to smoking have rarely been empirically explored.

One potential construct linking posttraumatic stress symptom severity and smoking is perceived stress. Perceived stress reflects one’s perception of his/her global life stress (Norris, 1992) and is unique from negative affect because it taps into the stress appraisal process (Cohen et al., 1983). Perceived stress is higher in current smokers than nonsmokers and recent quitters (Carey et al., 1993; Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990; Ng & Jeffery, 2003) and predicts higher odds of quit failure and shorter time to smoking relapse (al’Absi et al., 2005). Moreover, 'successful quitters' report decreased perceived stress (Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990) whereas those who relapse report greater perceived stress (Carey et al., 1993). Biologically, smoking alters stress management systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system, which subsequently contributes to smoking maintenance and more difficulty quitting (Richards et al., 2011). In terms of trauma-exposure, trauma-exposed persons report higher levels of perceived stress than non-trauma exposed person (Norris, 1992). Evidence also suggests that more severe PTSD symptoms and greater perceived stress frequently co-occur (Besser et al., 2009; Frasier et al., 2004). Indeed, greater perceived stress is associated with increased posttraumatic stress symptom severity (Hu et al., 2013; Hyman et al., 2007). Despite past work, research has not yet explored the role of perceived stress in the relation between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and smoking processes.

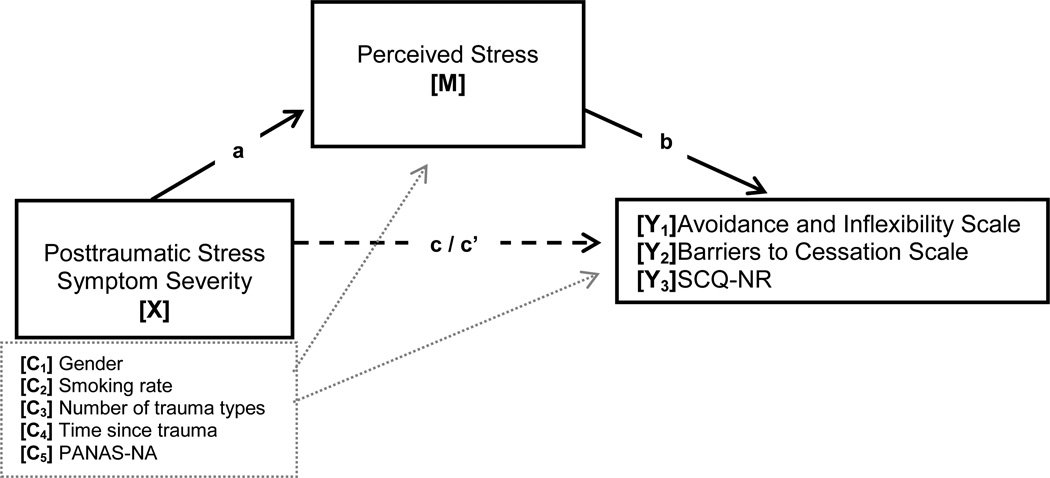

Trauma-exposed smokers who experience greater levels of posttraumatic stress symptom severity may be prone to higher levels of perceived stress (Hyman et al., 2007). As a result, in the absence of alternative adaptive regulatory strategies, smoking may be used among trauma-exposed smokers to manage stressful negative mood states in the short term; including smoking inflexibly in response to negative mood states and maintaining expectancies that smoking can relieve negative affect, and perceiving quitting to be more difficult. With this background, the current study tested the hypotheses that, among adult, treatment-seeking trauma-exposed daily smokers, perceived stress would explain the relation between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and (1) the tendency to respond with avoidance/inflexibility in the presence of aversive smoking-related thoughts, feelings, or internal sensations; (2) perceived barriers to smoking cessation; and (3) negative affect reduction/negative reinforcement expectancies from smoking through perceived stress.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 179 treatment-seeking, trauma exposed, adult daily smokers (48.0% female; Mage = 41.17; SD = 12.55) who endorsed at least one lifetime Criterion A traumatic event according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSMIV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Participants were asked to identify one traumatic event that was most disturbing. Traumatic events identified as most disturbing included accident (30.7%), life threatening illness (12.3%), non-sexual assault by a stranger (9.5%), sexual assault by someone participant knew (8.9%), non-sexual assault by someone participant knew (8.9 %), disaster (5.0%), sexual assault by a stranger (3.9%), sexual contact while under 18 with someone 5 or more years older (2.8%), combat (2.2%), imprisonment (1.1%), torture (1.1%), and other event (12.8%). Only participants who reported smoking at least 8 cigarettes a day during the past year, as indexed by the Smoking History Questionnaire (Brown et al., 2002), were included. Exclusion criteria included current suicidality and psychosis. See Table 1 for the sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| M(SD)/N[%] | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.17 (12.55) | 18–65 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 93 [52.0] | -- |

| Female | 86 [48.0] | -- |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 158 [88.3] | -- |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 10 [5.6] | -- |

| Black Hispanic | 1 [0.6] | -- |

| Hispanic | 4 [2.2] | -- |

| Asian | 2 [1.1] | -- |

| Other | 4 [2.2] | -- |

| Education Completed | ||

| Less than high school | 9 [5.0] | -- |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 34 [19.0] | -- |

| Some college | 57 [31.8] | -- |

| Associates degree | 16 [8.9] | -- |

| Bachelor degree | 32 [17.9] | -- |

| Some graduate or professional school | 13 [7.3] | -- |

| Graduate or professional school | 18 [10.1] | -- |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married or living with someone | 77 [43.0] | -- |

| Widowed | 5 [2.8] | -- |

| Separated | 5 [2.8] | -- |

| Divorced or annulled | 32 [17.9] | -- |

| Never married | 60 [33.5] | -- |

| Smoking rate | 18.42 (7.64) | 8–40 |

| Number of trauma types | 3.17 (1.73) | 1–9 |

| Time since [index] trauma | 5.38 (0.99) | 2–6 |

| Health | 0.48 (0.72) | 0–3 |

| PANAS-NA | 18.88 (7.39) | 10–44 |

| PDS | 8.19 (9.54) | 0–42 |

| PSS | 24.47 (7.97) | 1–43 |

| Avoidance & Inflexibility | 46.25 (10.68) | 17–65 |

| Barriers to Cessation | 24.72 (10.92) | 0–52 |

| SCQ-NR | 5.95 (1.63) | 1.58–9 |

Note. N = 179; M(SD) = Mean (Standard Deviation). PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Negative Affect subscale (Watson et al., 1988); PDS = Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa, 1995); PSS = Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983); SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequences Questionnaire Negative Reinforcement/Negative Affect Reduction Subscale (Brandon & Baker, 1991). Smoking rate = average number of cigarettes smoked pre day in the last week. Time since [index] trauma = time since the traumatic event identified as most disturbing on the PDS ranging from 1 “Less than one month [ago]” to 6 “More than 5 years [ago].”

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

Demographic information collected included gender, age, race, educational level, and marital status.

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS)

The PDS (Foa, 1995) is a 49-item self-report instrument that assesses trauma exposure and the presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Respondents report if they have experienced any of 13 traumatic event types (e.g., “natural disaster“, “sexual or non-sexual assault by a stranger”), including an “other” category, and then indicate which event was most disturbing. In the current study, only those participants indicating that they experienced, witnessed, and were confronted with a traumatic event that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury that was accompanied by a feeling of helplessness and terror (i.e., met DSMIV-TR defined criterion A trauma; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) were included. Participants report the frequency of 17 past-month PTSD symptoms for the most disturbing event endorsed according to a scale ranging from 0 (not at all/only once) to 3 (5 or more times a week/almost always). The PDS has evidenced excellent psychometric properties (Foa et al., 1997), including excellent internal consistency (alpha = .92) and good test-retest reliability (kappa = .74). The current study utilized the total score for the frequency of the 17 PTSD symptoms (α = .93). Two covariates were derived from this measure: (1) number of trauma types experienced was the total number of traumatic event types endorsed and (2) participants report how long ago the traumatic event occurred on a 6-point scale from 1 (Less than one month [ago]) to 6 (More than 5 years [ago]).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS (Cohen et al., 1983) assessed perceived stress. The PSS is a 14-item scale that measures the degree to which situations in one's life are appraised as stressful during the past month. Participants respond to feeling stressed on a 0 (never) to 4 (very often) scale. Item content reflects the degree to which respondents report experiencing life events as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and generally overloading (e.g., “How often have you felt that you were able to control the important things in your life?”). Seven items are reverse scored. The PSS score is derived by summing all items; total scores range from 0 to 56. The PSS has good internal consistency (r = .84 – .86) and test-retest reliability (r = .85; Cohen et al., 1983). In the present study, the PSS total score demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .88).

Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS)

The AIS assessed avoidance and inflexibility related to smoking (Gifford & Lillis, 2009). Participants responded to 13-items according to a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). Items included “How likely is it that these feelings will lead you to smoke?” and “To what degree must you reduce how often you have these thoughts in order not to smoke.” The AIS has demonstrated good internal consistency (Gifford & Lillis, 2009). Higher scores represent more smoking-based avoidance or inflexibility in the presence of uncomfortable or difficult sensations or thoughts, whereas lower scores suggest more ability to accept difficult feelings or thoughts without allowing them to trigger smoking. Past work has found good convergent and predictive validity of the AIS for smoking processes (Farris et al., in press; Zvolensky et al., 2014). The total score was utilized in the current study and the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .93).

Barriers to Cessation Scale (BCS)

The BCS assessed barriers, or specific stressors, associated with smoking cessation (Macnee & Talsma, 1995). The BCS is a 19-item measure on which respondents indicate, on a 4-point Likert-style scale (0 [not a barrier] to 3 [large barrier]), the extent to which they identify with each of the identified barriers to cessation. Researchers report good internal consistency regarding the total score, and good content and predictive validity of the measure (Macnee & Talsma, 1995). The total score was utilized and it demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .89).

Smoking Consequences Questionnaire (SCQ)

The SCQ (Brandon & Baker, 1991) is a 50-item self-report measure that assesses tobacco use outcome expectancies believed to underlie smoking motivation on a Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (completely unlikely) to 9 (completely likely). The measure consists of four key subscales: Positive Reinforcement/Sensory Satisfaction (15 items), Negative Reinforcement/Negative Affect Reduction (12 items), Negative Consequences (18 items), and Appetite-Weight Control (5 items). The entire measure and its factors exhibit good psychometric properties (Brandon & Baker, 1991; Downey & Kilbey, 1995). The present study utilized the SCQ-Negative Reinforcement/Negative Affect Reduction (SCQ-NR) subscale (e.g., “Smoking helps me calm down when I feel nervous”); internal consistency was excellent (α = .92).

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ)

The SHQ was used to assess smoking rate, years of daily smoking, and other characteristics (Brown et al., 2002). Smoking rate was obtained from the question, “Since you started regular daily smoking, what is the average number of cigarettes you smoked per day?” Furthermore, years a daily smoker was assessed by the question, “For how many years, altogether, have you been a regular daily smoker?”

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS)

The PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) measured the extent to which participants experienced 20 different feelings and emotions on a scale ranging from 1 (Very slightly or not at all) to 5 (Extremely). The measure yields two factors, negative and positive affect, and has strong documented psychometric properties (Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS negative affectivity subscale (PANAS-NA; 10 items) was utilized in the present study (α = .92).

Procedure

Adult daily smokers were recruited from the community to participate in a randomized controlled dual-site clinical trial examining the efficacy of two smoking cessation interventions. Individuals responding to study advertisements were scheduled for an in-person, baseline assessment to evaluate study inclusion and exclusion criteria. After providing written informed consent, participants completed an interview and a computerized battery of self-report questionnaires. Five hundred seventy-nine participants provided at least partial self-report data for the trial. The Institutional Review Board at each study site approved the study protocol; all study procedures and treatment of human subjects were conducted in compliance with ethical standards of the American Psychological Association. The current study is based on secondary analyses of baseline (pre-treatment) data for a sub-set of the sample with complete data for studied variables.

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted using bootstrapping techniques through PROCESS, a conditional modeling program that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). Bootstrapping is the recommended approach when data distribution is nonnormal or unknown (Kelley, 2005; Kirby & Gerlanc, 2013). An indirect effect is assumed to be significant if the confidence intervals (CIs) around the product of path a and path b (effect a*b) do not include zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Zhao et al., 2010). Models included PDS total as the predictor and PSS as the explanatory variable. Based on previous research (Bakhshaie et al., 2014; Garey et al., in press), covariates included gender, smoking rate, number of trauma types, time since trauma, and PANAS-NA. Three independent models were run with AIS (Model 1), BCS (Model 2), and SCQ-NR (Model 3) as criterion variables. All models were subjected to 10,000 bootstrap re-samplings and a 95-percentile confidence interval (CI) was estimated (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). Finally, given that the mediational analyses were conducted among cross-sectional data, we performed specificity analyses whereby we reversed the predictor (i.e., PDS) and proposed explanatory variable (i.e., PSS) to assess directionality of the observed effects and further strengthen results (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

Results

Of the 193 trauma-exposed daily smokers potentially eligible to be included in analyses, three outliers and 11 cases with missing data were removed; thus, 179 cases comprised the sample included in the analyses.

Participants were primarily White (88.3%) adults. Participants reported an average daily smoking rate of 18.4 (SD = 7.64) cigarettes per day and daily smoking for an average of 23.0 years (SD = 12.86). The majority (66.5%) of participants reported that the traumatic event occurred more than 5 years ago and an average of 3.17 (SD = 1.73) trauma event types. Table 1 reports sample characteristics.

PDS was positively and significantly correlated with all dependent variables. PSS was positively and significantly correlated with all dependent variables. All dependent variables positively and significantly correlated with one another, and PDS and PSS positively and significantly correlated with each other. Bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlations among variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gendera | -- | |||||||||

| 2. | Smoking ratea | −.15 | -- | ||||||||

| 3. | Number of trauma typesa |

−.02 | .03 | -- | |||||||

| 4. | Time since traumaa | −.06 | .09 | .06 | -- | ||||||

| 5. | PANAS-NAa | .18* | −.01 | .18* | −.20** | -- | |||||

| 6. | PDSb | .23** | −.03 | .36*** | −.19* | .52*** | -- | ||||

| 7. | PSSc | .20** | .09 | .14 | −.18* | .67*** | .50*** | -- | |||

| 8. | Avoidance & Inflexibilityd |

.20** | .09 | .10 | .09 | .23** | .18* | .28*** | -- | ||

| 9. | Barriers to Cessationd | .25** | −.003 | .04 | −.07 | .38*** | .29*** | .39*** | .61*** | -- | |

| 10. | SCQ-NRd | .23** | .03 | .08 | −.14 | .42*** | .25** | .46*** | .46*** | .54*** | -- |

Note. N = 179

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Covariate;

Predictor;

Explanatory Variable;

Outcome.

Gender: 1 = Male and 2 = Female; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Negative Affect subscale (Watson et al., 1988); PDS = Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa, 1995); PSS = Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983); SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequences Questionnaire Negative Reinforcement/Negative Affect Reduction Subscale (Brandon & Baker, 1991).

Regression Analyses

For smoking-specific avoidance/inflexibility, there was a significant total effect (R2= .11, F[6, 172] = 3.70, p = .002). The direct effect model with PSS was significant (R2 = .13, F[7, 171] = 3.69, p = .001). The indirect effect of PDS on AIS through PSS was significant (ab = .042, CI = .005 to .106). The specificity analysis with PDS and PSS reversed was non-significant (ab = .004, CI = −.061 to .084)

There was a significant total effect for perceived barriers to cessation (R2 = .19, F[6, 172] = 6.56, p < .001). The direct effect model with PSS was significant (R2 = .21, F[7, 171] = 6.33, p < .001). Also, the indirect effect of PDS on BCS through PSS was significant (ab = .046, CI = .001 to .120). The specificity analysis with PDS and PSS reversed was non-significant (ab = .026, CI = −.019 to .098).

In regard to negative affect reduction/negative reinforcement expectancies, there was a significant total effect (R2 = .21, F[6, 172] = 7.61, p < .001). The direct effect model with PSS was significant (R2 = .26, F[7, 171] = 8.47, p < .001). The indirect effect of PDS on SCQ-NR through PSS was significant (ab = .011, CI = .004 to .022). The specificity analysis with PDS and PSS reversed was non-significant (ab = −.003, CI = −.012 to .003). Regression results for paths a, b, c, and c’ are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results from regression models

| Y | Model | b | SE | t | p | CI (lower) | CI (upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PDS →PSS (a) | .168 | .057 | 2.954 | .004 | .056 | .280 |

| PSS → AIS (b) | .247 | .135 | 1.827 | .070 | −.020 | .514 | |

| PDS → AIS (c’) | .013 | .103 | .129 | .898 | −.191 | .217 | |

| PDS → AIS (c) | .055 | .102 | 0.540 | .590 | −.146 | .255 | |

| PDS → PSS → AIS (a*b) | .042 | .024 | .005 | .106 | |||

| 2 | PSS → BCS (b) | .272 | .132 | 2.056 | .041 | .011 | .533 |

| PDS → BCS (c’) | .090 | .101 | 0.885 | .377 | −.110 | .289 | |

| PDS → BCS (c) | .135 | .100 | 1.358 | .176 | −.061 | .332 | |

| PDS → PSS → BCS (a*b) | .046 | .029 | .001 | .120 | |||

| 3 | PSS → SCQ-NR (b) | .063 | .019 | 3.313 | .001 | .026 | .101 |

| PDS → SCQ-NR (c’) | −.011 | .015 | −0.743 | .458 | −.040 | .018 | |

| PDS → SCQ-NR (c) | −.0002 | .015 | −0.015 | .990 | −.029 | .029 | |

| PDS → PSS → SCQ-NR (a*b) | .011 | .005 | .004 | .022 | |||

Note. a = Effect of X on M; b = Effect of M on Yi; c = Total effect of X on Yi; c’ = Direct effect of X on Yi controlling for M; Path a is equal across all models; therefore, it presented only in the model with Y1 to avoid redundancies. N for analyses of models Y1–Y4 included 179 cases. The standard error and 95% CI for a*b are obtained by bootstrap with 10,000 re-samples. PDS (Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; Foa, 1995) is the predictor, PSS (Perceived Stress Scale; Cohen et al., 1983) is the explanatory variable, and AIS (Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale; Gifford & Lillis, 2009), BCS (barriers to smoking cessation, and SCQ-NR (Smoking Expectancies for Negative Affect Reduction Subscale; Brandon & Baker, 1991) are the outcome variables.

CI (lower) = lower bound of a 95% confidence interval; CI (upper) = upper bound; → = affects.

Significant indirect effects are bolded.

Discussion

As hypothesized, perceived stress had an indirect effect on posttraumatic stress symptom severity and the tendency to respond with inflexibility/avoidance in the presence of aversive smoking-related thoughts, feelings, or internal sensations, perceived barriers to smoking cessation, and negative affect reduction/negative reinforcement expectancies. The observed effects were evident above and beyond the variance accounted for by gender, smoking rate, number of trauma types, time since trauma, and the propensity to experience negative affect. Although the present research design did not permit explication of the temporal ordering of the observed associations, confidence in the observations was strengthened by evaluating an alternative model in which the predictors were reversed; all alternative models were non-significant. These data are in line with the perspective that posttraumatic stress symptom severity may be related to perceived stress, which in turn, is related to the studied smoking dependent variables.

Clinically, these data suggest that smoking cessation programs for trauma-exposed individuals may benefit from stress management psychoeducation and skills training that integrates the linkage between posttraumatic stress and perceived stress in terms of smoking-based emotion regulation and cognition. Although additional research is needed, it may be that smoking cessation programs for trauma-exposed individuals that incorporate stress management skills training may be more efficacious over standard smoking cessation programs. Although addressing PTSD may yield positive results for trauma-exposed smokers who seek clinical services, some trauma-exposed smokers may benefit by targeting specific life stressors, including work, interpersonal, and familial stressors, which may subsequently facilitate changes in smoking cognitions and behavior and. Thus, stress-management interventions may be a useful compliment or supplementary intervention tactic for trauma-exposed smokers, particularly those who may be less apt to 'engage' with therapeutic tactics oriented fully on PTSD symptoms.

Although not the primary study aims, posttraumatic stress symptom severity and perceived stress were related, but distinct constructs. Indeed, these two constructs shared approximately 25% of variance with one another. This observation lends further empirical support to the construct validity of these two affective vulnerability processes in tobacco research/practice. Additionally, contrary to prior research, no association emerged between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and smoking rate (Feldner, Babson, & Zvolensky, 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2008); this finding suggests that these variables may not be related in trauma-exposed, treatment seeking smokers. However, the mild range of posttraumatic stress symptom severity reported may have contributed to this set of findings. Thus, future work should examine these relations with an independent sample of smokers with greater posttraumatic stress symptom severity to potentially resolve inconsistent findings.

There are a number of study limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study design does not allow for testing of temporal sequencing. Future studies should examine these relations prospectively. Second, our sample consisted of primarily White, community-recruited, treatment-seeking, trauma-exposed daily cigarette smokers with a moderate smoking rate. Future studies may benefit by sampling ethnically diverse, lighter and heavier smokers to ensure the generalizability of the results to the general smoking population. Finally, we did not have sufficient data to complete analyses on smokers with PTSD and the observed level of self-reported posttraumatic stress symptoms, as noted earlier, was in the mild range. To further gauge the clinical significance of the current findings for smokers with PTSD, it would be important for future work to replicate this model with smokers demonstrating higher levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms expression and/or PTSD. Yet, as PTSD is only one disorder associated with smoking (Lasser et al., 2000), future research should extend this work across other disorders that are highly comorbid with smoking, including depression and anxiety.

Overall, the present study serves as an initial investigation into the nature of the association among posttraumatic stress symptom severity, perceived stress, and a relatively wide range of clinically significant smoking processes with adult treatment-seeking, trauma-exposed smokers. The findings of the current study suggest perceived stress may represent a possible explanatory variable in the relation between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and certain smoking processes. Future research should focus on understanding these relations among those with PTSD as well as how these relations may differentially relate to smoking across specific PSTD symptom clusters. Additionally, future work is needed to better understand the extent to which trauma-exposed smokers with symptoms of posttraumatic stress may benefit from clinically addressing perceived stress during smoking cessation treatment.

Figure 1.

Proposed model: Perceived stress as a potential explanatory variable for the effect of posttraumatic stress symptom severity on cognitive-bases processes of smoking.

Note: a = Effect of X on M; b = Effect of M on Yi; c = Total effect of X on Yi; c’ = Direct effect of X on Yi controlling for M; a*b = Indirect effect of M; five separate models were conducted for each criterion variable (Y1–4). PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Negative Affect subscale (Watson et al., 1988); SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequences Questionnaire Negative Reinforcement/Negative Affect Reduction Subscale (Brandon & Baker, 1991).

Highlights.

Posttraumatic stress symptom severity (PSS) relates to perceived stress for smokers.

Perceived stress is associated with smoking processes among trauma-exposed smokers.

Perceived stress indirectly links PSS and cognitive-based smoking processes.

Perceived stress may be clinically relevant to target among trauma-exposed smokers.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by a National Institute of Health grant awarded to Drs. Michael J. Zvolensky and Norman B. Schmidt (R01-MH076629-01A1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to psychological stress are associated with early smoking relapse. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, A. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR®. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshaie J, Zvolensky MJ, Brandt CP, Vujanovic AA, Goodwin R, Schmidt NB. The Role of Anxiety Sensitivity in the Relationship Between Emotional Non-Acceptance and Panic, Social Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms Among Treatment-Seeking Daily Smokers. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2014;7(2):175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y, Haynes M. Adult attachment, perceived stress, and PTSD among civilians exposed to ongoing terrorist attacks in Southern Israel. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47(8):851–857. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Baker TB. The smoking consequences questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;3(3):484. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Kalra DL, Carey KB, Halperin S, Richards CS. Stress and unaided smoking cessation: A prospective investigation. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1993;61(5):831. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of health and social behavior. 1983:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Lichtenstein E. Perceived stress, quitting smoking, and smoking relapse. Health Psychology. 1990;9(4):466. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey KK, Kilbey MM. Relationship between nicotine and alcohol expectancies and substance dependence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;3(2):174. [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Smoking-specific experiential avoidance cognition: Explanatory relevance to pre-and post-cessation nicotine withdrawal, craving, and negative affect. Addictive behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.026. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Babson KA, Zvolensky MJ. Smoking, traumatic event exposure, and posttraumatic stress: A critical review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(1):14–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Post-traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) Minneapolis: National Computer Systems. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9(4):445. [Google Scholar]

- Frasier PY, Belton L, Hooten E, et al. Disaster down east: Using participatory action research to explore intimate partner violence in eastern North Carolina. Health education & behavior. 2004;31(4 suppl):69S–84S. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Bakhshaie J, Vujanovic AA, Leventhal AM, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and cognitive-based smoking processes among trauma-exposed treatment-seeking smokers: The role of dysphoria. Journal of Addiction Medicine. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000091. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Lillis J. Avoidance and inflexibility as a common clinical pathway in obesity and smoking treatment. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(7):992–996. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Methodology in the social sciences. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hu E, Koucky EM, Brown WJ, Bruce SE, Sheline YI. The role of rumination in elevating perceived stress in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0886260513511697. 0886260513511697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Paliwal P, Sinha R. Childhood maltreatment, perceived stress, and stress-related coping in recently abstinent cocaine dependent adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(2):233. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K. The effects of nonnormal distributions on confidence intervals around the standardized mean difference: Bootstrap and parametric confidence intervals. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2005;65(1):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Gerlanc D. BootES: An R package for bootstrap confidence intervals on effect sizes. Behavior Research Methods. 2013;45(4):905–927. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. Jama. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnee CL, Talsma A. Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nursing Research. 1995;44(4):214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng DM, Jeffery RW. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychology. 2003;22(6):638. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1992;60(3):409. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Reserch and Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Stipelman BA, Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB, Sinha R, Lejuez C. Biological mechanisms underlying the relationship between stress and smoking: state of the science and directions for future work. Biological psychology. 2011;88(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer S, Barnow H, Völzke U, John HJ, Freyberger HJ. Grabe Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and physical illness: findings from the general population. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(9):1012–1017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bc76b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37(2):197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, Smits JA. The Role of Smoking Inflexibility/Avoidance in the Relation Between Anxiety Sensitivity and Tobacco Use and Beliefs Among Treatment-Seeking Smokers. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Gibson LE, Vujanovic AA, et al. Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on early smoking lapse and relapse during a self-guided quit attempt among community-recruited daily smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(8):1415–1427. doi: 10.1080/14622200802238951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]