Abstract

Adolescent Latinas in the United States (US) are disproportionately affected by early pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in comparison to their non-Hispanic white counterparts. However, only a few studies have sought to understand the multi-level factors associated with sexual health in adolescent Latinas. Adhering to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we conducted a systematic literature review to better understand the correlates and predictors of sexual health among adolescent Latinas in the US, identify gaps in the research, and suggest future directions for empirical studies and intervention efforts. Eleven studies were identified: five examined onset of sexual intercourse, nine examined determinants of sexual health/risk behaviors (e.g., number of sexual partners, condom use etc.), and three examined determinants of a biological sexual health outcome (i.e., STIs or pregnancy). Two types of variables/factors emerged as important influences on sexual health outcomes: proximal context-level variables (i.e., variables pertaining to the individual's family, sexual/romantic partner or peer group) and individual-level variables (i.e., characteristics of the individual). A majority of the studies reviewed (n=9) examined some aspect of acculturation or Latino/a cultural values in relation to sexual health. Results varied widely between studies suggesting that the relationship between individual and proximal contextual variables (including acculturation) and sexual health may be more complex than previously conceived. This review integrates the findings on correlates and predictors of sexual health among adolescent Latinas, and supports the need for strengths-based theoretically guided research on the mechanisms driving these associations.

Keywords: Latina, Hispanic, sexual health, sexual initiation, sexual risk, HIV, STI, pregnancy

Introduction

Early pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disproportionately affect adolescent Latinas compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts (Franzetta et al., 2007; Ventura et al., 2014). In 2012, the birthrate for adolescent Latinas 15-19 years old was more than twice as high as their non-Hispanic white adolescents (Ventura et al., 2014). Similarly, in 2010, the rate of HIV infection among 13-24 year old Latinas was over 3 times as high as white female adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). In 2012, rates of sexually transmitted infections (STI) for adolescent Latinas between 15-19 were considerably higher than white female counterparts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014a, b, c).

Between 2000 and 2010 there was a dramatic increase in the Latino/a population in the US, particularly Latino/a youth (Passel et al., 2011). Given these sexual health disparities and growing population of young Latinos/as, it is important for research to examine factors associated with sexual health outcomes among Latino/a adolescents. However, only a few studies have sought to understand the multi-level factors associated with sexual health in adolescent Latinas. Despite wide consensus regarding the importance of gender in understanding sexual health disparities (Cardoza et al., 2012; Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004; Tolman and McClelland, 2011) even fewer studies have examined these factors among adolescent Latinas (most aggregate males and females). The goals of this systematic review were to: (1) summarize the literature on determinants of adolescent Latinas sexual health outcomes (sexual initiation, sexual health/risk and biological sexual health outcomes), (2) identify gaps in the research, and (3) suggest future directions for studies and interventions. This work was guided by the Socio-Ecological Model of Sexual Health (SEMSH) (Raffaelli et al., 2012; Tolman and McClelland, 2011). This model views the individual as nested in a set of socioecological levels of influence (i.e., individual, dating/romantic relationships, social relationships, and sociocultural context) and highlights the importance of gender in understanding sexual health.

We followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines in the development of this review (Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015).

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search of three databases (PsychInfo, PubMed, and Google Scholar). Searches were limited to peer-reviewed, original studies. Given our interest in recent literature, we limited the search to the last 11 years. Terms cross-referenced in multiple searches (utilizing Boolean terms) were: adolescent Latinas/Latinos, sexual health, sexual initiation, sexual risk, STI/STD, pregnancy, and HIV. Terms were chosen based on our population of study and 4 sexual health outcomes of interest. We included quantitative empirical studies that met all criteria: were published in peer-reviewed journals or edited book chapters between January 1st 2004 and June 31st of 2015; had samples composed exclusively of Latinas or included individuals from other racial/ethnic backgrounds but stratified participants by race/ethnicity and reported results separately; had samples composed exclusively of female Latinas or included males but stratified the sample by gender and reported results separately or conducted post-hoc analyses to examine gender differences; had samples composed exclusively of adolescent Latinas ages ≥11 and ≤21 at baseline or included wider age-ranges but stratified the sample by age-group and reported results separately; and examined correlates or predictors of at least one of our dependent variables of interest. Given that “adolescence” has been defined in many different ways; we purposefully chose a wide age-range in order to encompass a full spectrum of studies with regard to adolescent sexual health development.

The literature search/selection process was conducted in four steps: key word search followed by title and abstract review; importing of relevant citations into citation manager with corresponding pdf link; review of full-text and exclusion of studies that did not meet review criteria or were duplicates; review of references list for each study for additional relevant studies; and repeating steps 1-4 until no new studies fitting the criteria could be identified. After article selection by the two authors, these data were extracted for each study: first author and year; source of data, location and year(s) when the data collection took place; study population; research design and theoretical framework; study objective(s); major findings (with regard to research question); and outcomes of interest. Given our goal of better understanding the determinants of sexual health among adolescent Latinas, studies that limited analyses to describing different racial/ethnic groups with regard to sexual health behaviors/outcomes (n=5) were excluded. Data was coded and content-analyzed based on the gender-specific and multi-level lens of the SEMSH (Raffaelli et al., 2012). A descriptive profile of the studies and a summary of the results is provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Correlates and Predictors of Sexual Health among Adolescent Latinas; 2004-2015.

| 1st Author (year) | Source of data, location, year(s) | Study Population N, % Latino/as, % female, age range & mean years (SD)1 | Research Design & Theoretical Framework | Study Objective (as stated by authors) | Major Findings2,3 | Outcome(s) of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bámaca-Colbert (2014) |

Source of data: Primary data collection Location: Metropolitan Area in Southwestern US Year(s): 2006-2010 |

N= 320 girls of Mexican-origin who had not experienced sexual intercourse at time 1 100% Latino/as 100% female 11–17 years of age at Time 1 |

Quantitative Longitudinal Study Ecological Model of Adolescent Sexuality |

To explore whether Time 1 sociocultural, interpersonal, and developmental variables predicted the occurrence and timing of 1st sexual intercourse reported 2.5 and 3.5 years later. |

|

Sexual initiation |

| Gilliam (2011) |

Source of data: Primary data collection Location: Two community-based outpatient clinics on Chicago's West Side Year(s): 2003-2005. |

N=143 Non-pregnant Latina adolescents, predominantly Mexican. (Young adults were included in this study but their data was analyzed separately. Only adolescent data has been included in this review.) 100% Latino/as 100% female 13-20 years of age Median age: 19 years |

Quantitative Cross-sectional Study | To compare culturally relevant factors associated with ever having used an effective method of contraception (i.e., intrauterine device [IUD], contraceptive implants, depot metroxy-progesterone acetate injection, metroxy-progesterone acetate/estradiol cypionate, contraceptive patch, or contraceptives pills) among a cohort of predominantly Mexican American females. | In multivariate analyses the following predicted effective contraceptive use among Latina adolescents:

|

Ever Use of Very Effective Contraception (IUD, implants, pills etc.) |

| Guilamo-Ramos (2009) |

Source of data: Primary data collection Location: New York City Year(s): 2006-2007 |

N= 702 Latino 8th graders and their mothers in New York City 100% Latino/as 52.1% female 8th grade students |

Quantitative Cross-sectional Study | Examine the relationship between acculturation, familismo and HIV-related sexual risk behavior. | Among female participants:

|

HIV-related Sexual Risk |

| Lee (2010) |

Source of data: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Location∷ Nation-wide survey Year(s): Waves I - III |

N= 1,073 Latina adolescents 100% Latino/as 100% female 11-20 years of age at Wave I & 18-27 at Wave 3 At Wave I 28.6% of participants were 11-14, 70.2% of participants were 15-18 and 1.2% of participants were 19-20. |

Quantitative Longitudinal Study | To examine the longitudinal association between Latina adolescents' level of acculturation and multiple sexual risk outcomes, including self-report STD diagnosis, four or more life-time sex partners, regret of sexual initiation after alcohol use, and lack of condom use during young adulthood. | Multivariate analyses assessed the longitudinal association between predictors at Wave 1 and sexual risk behaviors at Wave 3. These indicated that:

|

Sexual Risk Behaviors (Items examined separately/not collapsed into measure: History of STD, 4 or more sexual partners, regret of initiation after alcohol use, not using condom during recent sex STDs (self reported) |

| Ma (2014) |

Source of data: Primary data collection Location: Southeastern US |

N= 226 Latino adolescents; data collected through purposive sampling 100% Hispanic 53% female 13-16 years of age Mean Age (SD): 14.4 (1.0) Years |

Quantitative Cross-sectional Study | Examine the relationship between acculturation, core Latino values and sexual risks among Latino adolescents. | Stepwise regression analyses showed:

|

Ever had sexual intercourse Age at first sexual intercourse Number of sexual partners Condom use at first sexual intercourse Condom use frequency Intention to have sex while in secondary school |

| McDonald, (2009) |

Source of data: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Location∷ Nation-wide survey Year(s): 1997-2003 |

N= 1614 Hispanic adolescents and a participating parent (parent data only collected at baseline) of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central/South American or other origin. 100% Latino/as 48.8% female 12-16 years of age at baseline |

Quantitative Longitudinal Study | To explore relationships between immigration measures and risk of reproductive and sexual events among U.S. Hispanic adolescents. | Interaction Analyses Showed:

|

Transition to Sexual Intercourse before 18 Consistent Contraceptive Use (100%) Live birth |

| Raffaelli (2012) |

Source of Data: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Location: Nation-wide survey Year(s): Wave I |

N= 3162 Latino/a and Asian American boys and girls 69.3% Latino/as 50.6 % female (in Latino/a sub-sample) 7th to 12th grade |

Quantitative Cross-sectional Study Integrative Ecological Model of Immigrant Adolescent Sexuality |

To examine differences across immigrant generations in three sexual behaviors: ever had sexual intercourse, age at 1st intercourse and use of birth control at 1st sexual intercourse. |

|

Sexual Initiation Mean Age at 1st Sex Birth Control at 1st Sex |

| Rocca (2010) |

Source of data: Mission Teen Health Project (a prospective cohort study) Location: San Francisco, California Year(s): 2001-2004 |

N= 213 Latina adolescents in San Francisco who completed 2 consecutive study visits over a 2-year period 100% Latino/as 100% female 15-19 years of age Mean age (SD): 16.1 (1.5) Years |

Quantitative Longitudinal Study | Evaluating the mediating role of pregnancy intentions in the relationships between pregnancy and risk factors identified in previous research. |

|

Pregnancy |

| Smith (2015) |

Source of data: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Location: Nation-wide Survey Year(s): Waves I and III (1995-2002) |

N= 1,168 Hispanic females in Wave I who participated in Wave III and answered all of the questions used to create the outcome variable (i.e., sexual risk). 100% Hispanic 100% female 12-20 years of age Mean age (SD): 15.8 (1.7) Years |

Quantitative Longitudinal Study. Ecological Systems Theory |

To explain how intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity and acculturation predict risky sexual behavior using Structural Equation Modeling. | Structural equation modeling showed:

Acculturation (measured with 2 item scale regarding generation and language spoken at home) was associated with increased sexual risk (1 unit increase in acculturation resulted in .37 [p<.001] increase in sexual risk). |

Sexual Risk |

| Schwartz (2014) |

Source of data: Primary data collection Location: Miami and Los Angeles Year(s): 2010-2011 |

N= 302 recently immigrated (5 years or less) Hispanic adolescents primarily from Mexico and Cuba. 100% Latino/as 47% female 14-17 Years of age Mean age (SD): 14.5 (.88) Years |

Quantitative Longitudinal Study | Evaluate the “immigrant paradox” by ascertaining the effects of multiple components of acculturation on substance use and sexual behavior among recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. | Structural Equation Model did not fit equivalently across gender, so analyses were separated for males and females. Among girls:

|

Number of sexual partners Number of oral sex partners Frequency of unprotected sex |

| Villarruel (2007) |

Source of Data: Primary data collection Location: North Philadelphia Year(s): 2000-2004 |

N=233 Hispanic/Latino/a youth 100% Latino/a 48.1% female Years of age Mean age (SD): 15.4 Mean age (1.5) Years |

Quantitative Cross-sectional Study Theory of Planned Behavior |

Regression analyses by gender showed that:

|

Past condom use |

Mean age, standard deviation, and age range were reported when available. Where not available the distributional property measures that were available in the article (e.g., median) were reported.

Only findings directly pertaining to our dependent variables of interest were included.

Odds ratios, adjusted odds ratios, p-values, and confidence intervals were reported where available Notes: OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; SE: standard error

Full Model HRs provided.

Table 2. Study Characteristics.

| First Author (year) | Dependent Outcomes | Sample Type | Data Collection Type | Study Design | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Sexual Intercourse (n=5) | Sexual Behaviors/Sexual Health (n=9) | STIs/Pregnancy (n=3) | Males & Females1 (n=6) | All Female (n=5) | Add Health2 (n=4) | Primary Data Collection (n=7) | Cross-Sectional (n=5) | Longitudinal (n=6) | |

| Bámaca-Colbert (2014) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Gilliam (2011) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Guilamo-Ramos (2009) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Lee (2010) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Ma (2014) | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| McDonald (2009) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Rafaelli (2012) | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Rocca (2010) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Schwartz (2014) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Smith (2015) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Villarruel (2007) | X | X | X | X | |||||

Sample stratified by gender.

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health

Results

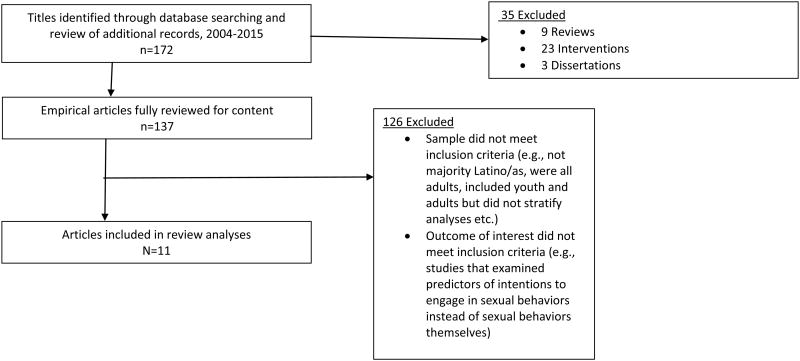

We identified 215 relevant titles and abstracts based on literature searches; 172 were selected for abstract review. After abstract review, 35 were excluded because: 9 were literature reviews, 23 were interventions, and 3 were dissertations. We conducted full-reviews of the remaining 137 studies. After full-reviews, 11 studies met all of the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (See Figure 1). Four of the studies utilized a behavior-change theory (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior) or broad theoretical framework (e.g., Ecological Systems Theory) (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Raffaelli et al., 2012; Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007). Five examined onset of sexual intercourse (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Lee and Hahm, 2010; Ma et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2009; Raffaelli et al., 2012), nine examined sexual health/risk behaviors (Gilliam et al., 2011; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Lee and Hahm, 2010; Ma et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2009; Raffaelli et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2012; Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007) and three examined a biological sexual health outcome (Lee and Hahm, 2010; McDonald et al., 2009; Rocca et al., 2010). (See Table 2.)

Figure 1. Selection Process for Systematic Review of the Literature.

In light of the SEMSH we found that two types of variables/factors emerged as important influences on sexual health outcomes: proximal context-level variables (i.e., pertaining to the individual's family or sexual/romantic partner) and individual-level variables (i.e., psychosocial attributes or acculturation-level).

Proximal Context-Level

Four of the studies identified familial or partner-level influences on sexual health outcomes (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Gilliam et al., 2011; Lee and Hahm, 2010; Rocca et al., 2010). In their study of 320 Mexican-American young women from a Southwestern city, Bámaca-Colbert et al. (2014) found that adolescent Latinas who lived with a stepparent (compared with two biological parents) were at greater risk for early intercourse (HR 1.92(SE: 0.35); p<0.001). In another study, Lee and Hahm (2010) found that adolescent Latinas whose parents had higher educational attainment were more likely to regret sexual initiation after alcohol use (OR 1.15; 95% CI= 1.01-1.30, p=0.035) and less likely to not use condoms during recent sex (OR 0.89; 95% CI= 0.82-0.96, p=0.004) in their Add Health sample (n=1073).

Two studies found significant associations between a partner-level variable and a sexual health outcome (Gilliam et al., 2011; Rocca et al., 2010). Gilliam and colleagues (2011) found that partner communication about birth control predicted effective contraceptive use among 143 non-pregnant adolescent Latinas in Chicago (OR 5.40; 95% CI= 2.07-14.13, p=0.001)(Gilliam et al., 2011). Rocca and colleagues (2010) found that low relationship power (measured with 23-item scale) with a main partner (defined as someone with whom the participant had had sex with in the past six months and whom she considered to be “like a boyfriend”) was independently associated with higher risk of pregnancy (OR 3.3; 95% CI= 1.3-8.4; p<0.01) in their study of adolescent Latinas in San Francisco (Rocca et al., 2010). Having a main partner was also significantly associated with pregnancy in all of their models regardless of participants' reported level of relationship power (Rocca et al., 2010).

Individual-Level

All of the studies (n=11) identified at least one individual-level variable which influenced sexual health. Three types of individual-level variables/factors emerged: sociodemographic variables (n=1), psychosocial/behavioral attributes (n=5), and acculturation-level/cultural values (n=9).

In the only study to find a significant association between sociodemographic variables and a sexual health outcome in controlled analyses, Gilliam and colleagues (2011) found that the more children an adolescent had given birth to the more likely she was to use very effective contraception (i.e., intrauterine device, implants or pills) (OR 7.83; 95% CI= 3.25-18.91, p < 0.001) (Gilliam et al., 2011). Forty-three percent of the adolescent Latinas, 13-20 years old, in this Chicago sample had given birth to one child (Gilliam et al., 2011).

Five of the studies found at least one significant association between a psychosocial/behavioral variable and a sexual health/risk behavior (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Lee and Hahm, 2010; Rocca et al., 2010; Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007).

Villarruel et al. (2007) found that condom use intentions positively predicted condom use among 233 adolescent Latinas in North Philadelphia (β=.58). Similarly, Rocca and colleagues (2010) found that pregnancy wantedness was independently and positively associated with pregnancy (OR 2.6; 95% CI= 1.1-6.1; p<.05).

Lee and Hahm (2010) found that depressive symptoms during adolescence were associated with having 4+ lifetime sexual partners during young adulthood (OR 1.03; 95% CI= 1.01-1.06, p=0.021) (Lee and Hahm, 2010). Binge drinking was associated with regretting sexual initiation after alcohol use (OR 3.55; 95% CI= 1.44-8.78), increased odds of having 4+ lifetime sexual partners (OR 2.94; 95% CI= 1.88-4.60, p=0.000), and not using condoms during recent sex (OR 2.02, 95% CI= 1.18-3.46, p=0.012) in this same study.

Finally, two studies examined religiosity and sexual behaviors (Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007). Smith (2015) found that intrinsic religiosity (measured with three-item scale on beliefs and prayer) was protective against sexual risk (measured with seven-item scale) in his Add Health sample of 1,168 Latinas. Interestingly, he also found that extrinsic religiosity (measured with a two-item religious attendance scale) was associated with increased sexual risk (Smith, 2015). Finally, Villarruel et al. (2007) found that religiosity (measured with 5-point scale) significantly predicted condom use among adolescent Latinas (Villarruel et al., 2007).

Acculturation and Cultural Values

A majority of the studies (n=9) examined some aspect of acculturation or Latino/a cultural values in relation to sexual health (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Lee and Hahm, 2010; Ma et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2009; Raffaelli et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2012; Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007). Acculturation was measured in five different ways: scale-based measure, preferred language (Spanish/English), generation/amount of time in the US, country of origin, or a combination of these.

Two studies examined the effects of generation/time in the US on sexual initiation (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Raffaelli et al., 2012). Bámaca et al. (2014) found that first-generation immigrant girls (Mexican-born to Mexican-born mothers) were at greater risk than second-generation immigrant girls (US-born to Mexican-born mothers) to engage in early intercourse in their Southwestern sample. In contrast, Rafaelli et al. (2012) found that first-generation (foreign-born, came to the US at 13 or older) and 1.5-generation adolescent Latinas (foreign-born, moved the US before age 13) were less likely to report sexual intercourse compared to third-generation (US-born with US-born parents) adolescent Latinas (β=-2.93, SE 1.06; β=-0.80, SE 0.29, respectively) in their Add Health sample of 1,601 Latina girls (p<0.01 for both). They also found that first and third-generation adolescent Latinas reported greater birth control use (62.9% and 57.5%, respectively) than 1.5 and second-generation adolescent Latinas (51.3%).

In their Add Health sample of 1,614 Latino/a adolescents, McDonald and colleagues (2009) found that young women from “other” countries had greater odds of transitioning to sexual intercourse before age 18 (OR 1.6; 95% CI= 1.25-2.04; p<0.01) when compared to young women of Mexican-origin (McDonald et al., 2009). In this same study, second-generation adolescent Latinas (US-born with at least one biological foreign-born parent) had reduced odds of reporting 100% consistent contraceptive use compared with third-generation counterparts (US-born with biological US-born parents) (OR .28; 95% CI=.15-.53; p<.001)(McDonald et al., 2009).

One study used a combination of country of origin (US versus other) and language (English/Spanish) to examine the relationship between acculturation and sexual risk/protective behaviors (Lee and Hahm, 2010). They found that, compared to foreign-born adolescent Latinas who spoke Spanish at home: (1) US-born adolescent Latinas who spoke English at home were more likely to have 4+ lifetime sexual partners (OR 4.83; 95% CI= 2.09-11.15, p=0.000) and to have a history of STDs (OR 5.71; 95% CI= 1.30-25.04, p=0.021); (2) Foreign-born adolescent Latinas who spoke English at home were significantly more likely to regret sexual initiation after alcohol use (OR 10.67; 95% CI= 2.07-55.08, p=0.005), have 4+ life time sexual partners (OR 8.51; 95% CI= 2.48-29.23, p=0.001), and have a history of STDs (OR 6.62; 95% CI= 1.10-39.84, p=0.039).

Finally, three studies used scale-based measures of acculturation (Ma et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2012; Smith, 2015). Smith found that youth who were more “American-acculturated” (measured with two-item generation and language scale) engaged in higher sexual risk taking (measured with seven-item scale).

In their study of 226 Latino adolescents in the Southeast, Ma et al. (2014) found adolescent Latinas who had a stronger “Latino orientation” (measured with Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire-Short Version)(Guo et al., 2009; Szapocznik et al., 1980) reported sex with fewer sex partners (β=-.64, F(1,17)=11.72, p<.01)(Ma et al., 2014).

In their sample of 302 recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents from Miami and Los Angeles, Schwartz found that US-practices (measured with 12 items including speaking English and eating American food) was associated with a greater number of sexual partners (OR 1.87; 95% CI = 0.92-3.81; p<.10) and fewer reported instances of sex without condoms (OR 0.21; 95%CI=.09-.40; p<.001). Interestingly, they also found that Hispanic practices (measured with 12 items) was associated with fewer instances of unprotected sex (OR .33; 95% CI = 0.10-1.04; p<.10).

Finally, two studies examined Latino/a cultural values in relation to sexual health behaviors (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2014). Guilamo-Ramos (2009) found that familismo (closeness/interconnectedness between family members and felt responsibility toward each other; measured with 19-item scale) (Marín & Marín, 1991) was negatively associated with sexual risk behaviors (measured with 6 separate items). The “subjugation to the family” dimension of familismo (3-items including “A person should be a good person for the sake of his or her family”) was positively associated with lower risk (OR .10 - .39; p<.05 for all) (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009). Similarly, Ma et al. (2014) found that Latinas with greater levels of simpatía (maintaining harmony in relationships measured with 4-item scale) had an older sexual debut (β=.56, F(1,17) – 7.94, p<.05).

Discussion

Overall, the reviewed studies identified factors associated to sexual health among adolescent Latinas within the individual-level and social-level contexts of the SEMSH. Most studied the relationship between acculturation or Latino/a cultural values and sexual health outcomes. However, the study findings were not consistent between studies suggesting that these relationships are likely more complicated than what has been previously described in the literature.

Social Context

Two studies (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Lee and Hahm, 2010) showed a significant association between a family structure variable and adolescent sexual health. These findings confirm previous work (conducted with adolescent Latinos/as) which has found an association between familial characteristics and sexual health/risk (Santelli et al., 2000; Upchurch et al., 2001; Veliz, 2009). However, they fail to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these associations. For example, is it that parents with greater levels of educational attainment are more likely to speak to their teens about sexually protective behaviors or is educational attainment perhaps a proxy for other community-level risk factors (e.g., access to reproductive health services) known to the related decreased sexual health? Studies that can elucidate the mechanisms that drive these relationships, will be important in developing effective interventions.

Consistent with other studies (conducted with African American adolescent girls and gender and hererogenous race/ethnicity adolescent samples) (Davies et al., 2006; Manlove et al., 2007), one paper found that partner variables (i.e., lack of communication about birth control and low power in the relationship) were associated with increased sexual risk (Gilliam et al., 2011; Rocca et al., 2010). This finding is well-aligned with other adolescent research which has found a significant association between lower relationship power and increased sexual risk (Sanchez et al., 2013; Teitelman et al., 2008). It is likely that young women who report lower relationship power are less able to enact safe-sex practices, particularly in the context of main partnerships. These studies highlight the importance of programming focused on sexual health communication and relationship power.

Individual

Five studies found significant associations between sociodemographic or behavioral/psychosocial variables and sexual health (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Gilliam et al., 2011; Lee and Hahm, 2010; Rocca et al., 2010; Villarruel et al., 2007). One article found that adolescent Latinas who had previously given birth to one or more children were more likely to use very effective contraception (Gilliam et al., 2011). Previous research has suggested that Latina women become aware of contraceptive methods after the birth of their first-child (Gilliam et al., 2004). This work highlights the need for interventions that facilitate knowledge and access to very effective contraception for adolescent Latinas. Given traditional gender roles prescribing purity and virginity to young women (known as “marianismo”) this work must be undertaken in a culturally-aware and community-driven manner to be effective (Marin & Marin, 1991).

Binge drinking was associated with increased sexual risk (Lee and Hahm, 2010). These findings confirm other work which has also linked “problem-behaviors” to sexual risk and STDs in adolescents (Cook and Clark, 2005; Kann et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 2005) and highlight the need for youth programming that promotes sexual health as part of a broader healthy lifestyle interventions. For example, the SHERO's intervention by Harper and colleagues took a community-driven, strengths-based, culturally-affirming approach to intervention development and implementation including sessions on cultural pride and pressure to be a mother (Harper, Bangi, Sanchez, Doll, & Pedraza, 2009).

Two studies examined religiosity in relation to sexual risk (Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007). The first of these, consistent with other research conducted with Latino adolescents and mixed gender/race-ethnicity adolescents (Edwards et al., 2008; Vesely et al., 2004), found that higher levels of religiosity positively predicted condom use (Villarruel et al., 2007) contrasting previous work on church attendance (Manlove, 2006)

In more nuanced analyses, Smith (2015) found that intrinsic religiosity was protective against sexual risk while extrinsic religiosity was associated with increased sexual risk (Smith, 2015). This finding contradicted one study with college students which found both (intrinsic and extrinsic) to be protective from sexual activity and condom use (Zaleski and Schiaffino, 2000). Despite being widely-cited as a potentially important factor in Latino/as sexual health, the literature on religiosity and sexual health is mixed. More nuanced measures like the one used by Smith (2015) are important steps in better understanding the relationships between religion and sexual health (Lescano et al., 2009; Smith, 2015).

Acculturation/Cultural Values

Finally, a majority of the studies, examined some aspect of acculturation/cultural values in relation to sexual health behaviors and outcomes in adolescent Latinas. This work reflected the broader literature on the relationship between acculturation and sexual health for Latino adolescents (with samples including boys and girls) (Afable-Munsuz and Brindis, 2006; Raffaelli and Ontai, 2001), in that these studies had mixed results and did not tell “a clear story” about the association.

Two studies examined the relationship between immigrant generation and sexual initiation with contrasting results. While one of them found that first-generation immigrant girls were more likely to engage in early intercourse compared to second-generation girls the second found that first-generation and 1.5-generation girls were less likely to report sexual intercourse compared to third-generation girls (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Raffaelli et al., 2012). Although comparability across studies is limited given differences in sample compositions and designs, these contrasting results suggest that the association between generation and sexual initiation may not be linear as suggested by the widely-cited immigrant paradox (i.e., individuals from later immigrant generations will experience worse health outcomes than those from earlier ones (Raffaelli et al., 2012)). Immigrant generation may not be a sufficiently granular measure of acculturation to adequately capture its relationship to sexual initiation.

Nine studies examined the relationship between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors. Two of these (McDonald et al., 2009; Rafaelli et al., 2012), in line with Guarini et al. (2011) seem to suggest that second-generation adolescents may experience higher levels of sexual risk taking. However, it is possible that sexual risk and acculturation may not be linearly related to one another. Rafaelli's work, which found a protective effect for third-generation teens as well as first-generation teens, suggests that this relationship may be more complicated.

A third study adds additional insight to the idea of a potentially curvilinear relationship between acculturation and sexual health/risk behaviors. Lee and Hahm (2010) found that adolescent Latinas who had not been born in the US but spoke English at home had the highest levels of sexual risk (Lee and Hahm, 2010) when compared to foreign-born adolescent Latinas who spoke Spanish at home. Authors suggest that increased levels of acculturative stress among foreign-born youth who speak English at home may help explain this finding (Lee and Hahm, 2010). Future studies should further investigate whether the “stress” of acculturating somehow puts some youth in the middle of the continuum at risk (Afable-Munsuz and Brindis, 2006).

Finally, two studies examined the relationship between Latino/a cultural values and sexual health suggesting that espousing these Latino/a values is protective (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2014). These studies support the widely accepted, but understudied, notion that certain Latino/a values are important with regard to sexual health behaviors (Lescano et al., 2009; Marín, 2003). This has important implications for the development of culturally-affirming intervention programing.

Methodological Strengths and Weaknesses of Studies

The studies in this review were not without methodological flaws. For example, a majority of the studies drew their samples from Add Health data and other school-based datasets (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Lee and Hahm, 2010; McDonald et al., 2009; Raffaelli et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2012; Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007). Although this work provides important insight to school populations and allows for random sampling, these results are not generalizable to youth who are not and school and likely at higher risk for negative sexual health outcomes. Additionally, mixing Latino/a youth from different geographic areas, countries of origin etc. in the sample is problematic for generalizability in Latino/a studies. Several studies mitigated this issue by utilizing more homogeneous community and venue-based samples (Gilliam et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2014; Rocca et al., 2010); stratifying their analyses; or examining only 1 subgroup (etc. Puerto Ricans) (Bámaca-Colbert et al. 2014; Gilliam, 2011; Schwartz et al., 2012).

Additionally, a common measurement issue across studies were oversimplified measures of acculturation and religiosity that reduced these complicated and multi-dimensional constructs to several proxy items (e.g., language of preference or church attendance) (Gilliam et al., 2011; Lee and Hahm, 2010; McDonald et al., 2009; Raffaelli et al., 2012; Villarruel et al., 2007). It is likely that study results are mixed, in part, due to these measurements. On the other hand, some studies utilized well-constructed, scale-based, validated measures of acculturation and religiosity (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2012; Smith, 2015). One particularly excellent example of measurement development, overall, was Gilliam's survey development process, which was founded on formative qualitative interviews with the population of study (Gilliam et al., 2011).

Finally, given the sensitive nature of the subject matters examined in sexual health research and that all of the studies used some form of self-report, it is important to consider that social desirability could be a challenge to validity.

Future Research Considerations

Overall, several important conclusions can be gleaned dies. Despite empirical evidence that the correlates and predictors of sexual health operate differently for boys and girls, only 11 studies were found that examined these separately. More research focused on adolescent Latinas is needed to fully understand and address the sexual health disparities that disproportionately affect them.

Second, only a handful of studies utilized a theoretical framework to guide their research (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2014; Raffaelli et al., 2012; Smith, 2015; Villarruel et al., 2007) and only one used a theory of behavior change (Villarruel et al., 2007). A guiding theory is important in hypothesizing and testing potential connections between determinants of sexual health and sex behaviors or outcomes. Future studies should ensure the use of theory in guiding their research. This and more nuanced, evidence-based measures will facilitate comparability across study findings.

Third, many of the studies had an underlying deficit-focus. Very few mentioned sexual health promotion, instead focusing on “sexual risk”. Sexual initiation is a normative part of adolescent development (Tolman and McClelland, 2011). The focus of research and intervention programming should be on preventing early sexual initiation (which has been shown to predict negative sexual health outcomes) and promoting healthy sexual relationships. Future research should also emphasize youth assets and protective factors as some (e.g., community involvement, future aspirations etc.) have been linked to positive sexual health outcomes (Vesely et al., 2004).

Fourth, although previous research with mixed-gender samples suggests a significant association between community-level variables and sexual health (Browning et al., 2004; Cubbin et al., 2005; Upchurch et al., 2001), none of the studies reviewed included these variables. Future research should examine these to better understand how community-level context can impact sexual health.

Fifth, although this literature is useful describing the associations between correlates and predictors of sexual health behaviors and outcomes, it largely leaves the question of the intermediate mechanisms unanswered (Raffaelli et al., 2012). Theory-guided work that can explore the processes by which correlates and predictors of sexual health result in sexual health behaviors and outcomes is important (Raffaelli et al., 2012).

Sixth, this research is heavily focused on the effect of acculturation on sexual health of adolescent Latinas. However, despite the existence of several acculturation theories (Afable-Munsuz and Brindis, 2006), this work was largely undertaken a-theoretically. An underlying theory that describes how researchers believe acculturation is related to sexual health behaviors would be useful in describing these relationships. Additionally, few studies attempted to capture the construct in a multi-dimensional manner reducing it to language preference or immigrant generation. Understanding the relationship between acculturation and sexual health, will require more nuanced measures (Deardorff et al., 2010). Finally, an emphasis on cultural values more proximal to sexual health (e.g., importance of virginity, sexual silence) is warranted (Davila, 2005; Deardorff et al., 2010; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009).

Limitations & Conclusion

This study had several limitations. Firstly, given the emphasis on adolescent Latinas these results are not generalizable to other groups of adolescents. Secondly, given the heterogeneity across studies direct comparison and the use of more sophisticated review techniques (e.g., meta-analysis) were not possible. Despite these limitations, this study presents a significant contribution to the literature by summarizing the state of the science on adolescent Latinas and sexual health, an understudied group disproportionately affected by sexual health disparities. Additionally, the study demonstrates the need for: (1) Research about underlying processes and mechanisms driving the relationships between identified correlates and predictors of sexual health and (2) Strengths-based theoretical models to guide research and intervention development in this field.

Highlights.

Eleven studies were included in this systematic review of the literature.

Proximal context and individual-level variables influenced sexual health.

Nine studies examined acculturation or Latino/a cultural values; results varied.

Acculturation and sexual health link may be more complex than previously conceived.

Strengths-based theoretically guided research on underlying mechanisms is needed.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant number T32HS013852 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

Authors' contributions: MMA and IS conceived this paper and MMA drafted the article. Both authors revised it for content and approved the final version. MMA is the guarantor of this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Afable-Munsuz A, Brindis CD. Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: a literature review. Perspect Sex Repro H. 2006;38:208–19. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.208.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca-Colbert MY, Greene KM, Killoren SE, Noah AJ. Contextual and developmental predictors of sexual initiation timing among Mexican-origin girls. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:2353. doi: 10.1037/a0037772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz D, Shew M, Ofner S, Fortenberry JD. Pregnancy intentions and contraceptive behaviors among adolescent women: a coital event level analysis. J Adolescent Health. 2007;41:271–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Tolou-Shams M, Lescano C, Houck C, Zeidman J, Pugatch D, Lourie KJ Group, P.S.S. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual risk among African American adolescents and young adults. J Adolescent Health. 2006;39:444. e1–44. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41:697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoza VJ, Documet PI, Fryer CS, Gold MA, Butler J., 3rd Sexual health behavior interventions for U.S. Latino adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2012;25:136–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;2012:17. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chlamydia - Rates per 100,000 Population by Race/Ethnicity, Age Group, and Sex, United States, 2012. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2014a. Table 11B. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gonorrhea - Rates per 100,000 Population by Race/Ethnicity, Age Group and Sex, United States, 2012. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2014b. Table 22B. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and Secondary Syphilis - Rates per 100,000 Population by Race/Ethnicity, Age Group, and Sex, United States, 2012. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2014c. Table 36B. [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:156–64. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, Santelli J, Brindis CD, Braveman P. Neighborhood context and sexual behaviors among adolescents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Perspect Sex Repro H. 2005;37:125–34. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.125.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Person SD, Dix ES, Harrington K, Crosby RA, Oh K. Predictors of inconsistent contraceptive use among adolescent girls: findings from a prospective study. J Adolescent Health. 2006;39:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila YR. The social construction and conceptualization of sexual health among Mexican American women. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2005;19:357–68. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.2005.19.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Ozer EJ. Sexual values and risky sexual behaviors among Latino youths. Perspect Sex Repro H. 2010;42:23–32. doi: 10.1363/4202310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty IA, Minnis A, Auerswald CL, Adimora AA, Padian NS. Concurrent Partnerships Among Adolescents in a Latino Community: The Mission District of San Francisco, California. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:437–43. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000251198.31056.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Fehring RJ, Jarrett KM, Haglund KA. The influence of religiosity, gender, and language preference acculturation on sexual activity among Latino/a adolescents. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2008;30:447–62. [Google Scholar]

- Franzetta K, Schelar E, Manlove J. Trends in Hispanic Teen Births: Differences across States. Research Brief. Publication# 2007-22. Child Trends 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam ML, Neustadt A, Whitaker A, Kozloski M. Familial, cultural and psychosocial influences of use of effective methods of contraception among Mexican-American adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2011;24:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam ML, Warden MM, Tapia B. Young Latinas recall contraceptive use before and after pregnancy: a focus group study. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2004;17:279–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini T, Marks A, Patton F, Coll C. The immigrant paradox in sexual risk behavior among Latino adolescents: Impact of immigrant generation and gender. APPL DEV SCI. 2011;15:201–09. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, Lesesne C, Ballan M. Familial and cultural influences on sexual risk behaviors among Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Dominican youth. Aids Educ Prev. 2009;21:61–79. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Suarez-Morales L, Schwartz SJ, Szapocznik J. Some evidence for multidimensional biculturalism: Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance analysis on the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire–Short Version. Psychol Assessment. 2009;21:22. doi: 10.1037/a0014495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Bangi AK, Sanchez B, Doll M, Pedraza A. A quasi-experimental evaluation of a community-based HIV prevention intervention for Mexican American female adolescents: the SHERO's program. AIDS education and prevention : official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2009;21:109–23. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2013. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries. 2014;63(Suppl 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Hahm HC. Acculturation and sexual risk behaviors among Latina adolescents transitioning to young adulthood. J Youth Adolescence. 2010;39:414–27. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118:189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescano CM, Brown LK, Raffaelli M, Lima LA. Cultural factors and family-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:1041–52. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Malcolm LR, Diaz-Albertini K, Klinoff VA, Leeder E, Barrientos S, Kibler JL. Latino cultural values as protective factors against sexual risks among adolescents. J Adolescence. 2014;37:1215–25. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm S, Huang S, Cordova D, Freitas D, Arzon M, Jimenez GL, Pantin H, Prado G. Predicting condom use attitudes, norms, and control beliefs in Hispanic problem behavior youth: the effects of family functioning and parent-adolescent communication about sex on condom use. Health Educ Behav: the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2013;40:384–91. doi: 10.1177/1090198112440010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Ryan S, Franzetta K. Contraceptive use patterns across teens' sexual relationships: The role of relationships, partners, and sexual histories. Demography. 2007;44:603–21. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove JS, Terry-Humen E, Ikramullah EN, Moore KA. The Role of Parent Religiosity in Teens' Transitions to Sex and Contraception. J Adolescent Health. 2006;39:578–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14:186–92. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Marin BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro KE, Murray PJ, Ness RB, Bass DC, Tyus N, Cook RL. Depression, stress, and social support as predictors of high-risk sexual behaviors and STIs in young women. J Adolescent Health. 2006;39:601–03. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Manlove J, Ikramullah EN. Immigration measures and reproductive health among Hispanic youth: findings from the national longitudinal survey of youth, 1997-2003. The J Adolescent Health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2009;44:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119:76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. SYST REV. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D, Lopez MH. Hispanics account for more than half of nation's growth in past decade. Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/140.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Kang H, Guarini T. Exploring the immigrant paradox in adolescent sexuality: An ecological perspective 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. ‘She's 16 years old and there's boys calling over to the house’: an exploratory study of sexual socialization in Latino families. Cult Health Sex. 2001;3:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles. 2004;50:287–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca CH, Doherty I, Padian NS, Hubbard AE, Minnis AM. Pregnancy intentions and teenage pregnancy among Latinas: a mediation analysis. Perspect Sex Repro H. 2010;42:186–96. doi: 10.1363/4218610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MT, Bermudez M, Buela-Casal G. Power dynamics in adolescent couple relationships and risk of sexually transmitted infections and HIV. Curr Hiv Res. 2013;11:536–42. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140129104001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Lowry R, Brener ND, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1582. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Huang S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Villamar JA, Soto DW, Pattarroyo M, et al. Substance use and sexual behavior among recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents: effects of parent-adolescent differential acculturation and communication. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2012;125(Suppl 1):S26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SJ. Risky sexual behavior among young adult Latinas: Are acculturation and religiosity protective? J Sex Res. 2015;52:43–54. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.821443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, Fernandez T. Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. International Journal of intercultural relations. 1980;4:353–65. [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Ratcliffe SJ, Morales-Aleman MM, Sullivan CM. Sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, and condom use among minority urban girls. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:1694–712. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JC, Kao TC, Thomas RJ. The relationship between alcohol use and risk-taking sexual behaviors in a large behavioral study. Prev Med. 2005;41:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. J Res Adolescence. 2011;21:242–55. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Aneshensel CS, Mudgal J, McNeely CS. Sociocultural contexts of time to first sex among Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1158–69. [Google Scholar]

- Veliz E. Coming into their own---Adolescent Latinas in the United States. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura SJ, Hamilton BE, Matthews TJ. National and state patterns of teen births in the United States, 1940-2013. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2014;63:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesely SK, Wyatt VH, Oman RF, Aspy CB, Kegler MC, Rodine S, Marshall L, McLeroy KR. The potential protective effects of youth assets from adolescent sexual risk behaviors. J Adolescent Health. 2004;34:356–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Ronis DL. Predicting condom use among sexually experienced Latino adolescents. Western J Nurs Res. 2007;29:724–38. doi: 10.1177/0193945907303102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaleski EH, Schiaffino KM. Religiosity and sexual risk-taking behavior during the transition to college. J Adolescence. 2000;23:223–27. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]