Abstract

Background

This executive summary describes protocol for assessing patients with TMD and is based on the Schiffman et al, Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group.

Methods

The DC/TMD was developed using published Axis I physical diagnoses for the most common TMD. Axis I diagnostic criteria were derived from pertinent clinical TMD signs and symptoms. Axis II consists of psychosocial and behavioral questionnaires already in the public domain. The Axis I and Axis II diagnostic protocols were vetted and modified by a panel of experts. Recommended changes were assessed for diagnostic accuracy using the Validation Project’s data set, which formed the basis for the development of the DC/TMD.

Results

Axis I diagnostic criteria for TMD pain-related disorders have acceptable validity and provide definitive diagnoses for pain involving the TMJ and masticatory muscles. Axis I diagnostic criteria for the most common temporomandibular joint (TMJ) intra-articular disorders are appropriate for screening purposes only. A definitive diagnosis for TMJ intra-articular disorders requires computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Axis II questionnaires provide valid assessment of psychosocial and behavioral factors that can impact management of TMD patients.

Conclusions

The DC/TMD provides a questionnaire for the pain history in conjunction with validated clinical examination criteria for diagnosing the most common TMDs. In addition, it provides Axis II questionnaires for assessing psychosocial and behavioral factors that may contribute to onset and perpetuation of the patient’s TMD.

Practical Implications

The DC/TMD is appropriate for use in the clinical and research setting to allow for a comprehensive assessment of the individual with TMD.

Keywords: Temporomandibular joint disorders, temporomandibular dysfunction, research, orofacial pain, myofascial pain, masticatory muscles, diagnostic challenge, facial pain, clinical protocols, NIH (National Institutes of Health)

Introduction

In 1992, the seminal paper, the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) was published.1 The RDC/TMD had content validity because it was developed by a panel of TMD experts based on empirical data and a comprehensive review of the literature. This review included a critique of the different TMD diagnostic classification schemes in use at that time. However, the RDC/TMD went beyond standard classification approaches for TMD and proposed a dual axis assessment. Axis I included the standard diagnostic criteria for the most common TMD based on TMD clinical signs and symptoms. Axis II took the assessment further by including assessment of psychosocial and behavioral factors. Thus Axis I described the most common physical disorders while Axis II described aspects of the person who had the disorder. This was a paradigm shift. Only now are other pain-related diagnostic classifications adapting multi-axis assessments.2 The RDC/TMD Axes I and II were subsequently translated into 20 languages and have been used extensively in research-based publications.

The authors of the RDC/TMD stated from the beginning that there was a need to assess the criterion validity of the Axis I physical diagnoses. Criterion validity required assessing these diagnostic criteria against a gold standard (i.e., reference standard3). Subsequently, the multi-site Validation Project assessed the criterion validity of the RDC/TMD Axis I diagnostic criteria using credible gold standard diagnoses and concluded that these diagnostic criteria needed improvement.4 Briefly, the gold standard diagnoses for the pain-related disorders were established by consensus between two TMD and orofacial pain experts at each of three study sites using a comprehensive history, physical examination and a panoramic radiograph. The gold standard diagnoses for TMJ intra-articular disorders were established by board certified radiologists using bilateral temporomandibular joint [TMJ] magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and computed tomography [CT]) and blinded to the subject’s clinical presentation. All examiners and radiologists were calibrated and assessed annually for their reliability.5 Axis II questionnaires assessing psychosocial factors were shown to be sufficiently reliable and valid.6 The Validation Project subsequently published revised validated Axis I TMD diagnostic criteria for pain-related TMD and screening criteria for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) intra-articular disorders.5 These authors recommended that a panel of international experts in TMD and other pain conditions be convened to develop an expert-based DC/TMD assessment protocol that could be assessed against the credible gold standard developed in the Validation Project.7 The goal was to develop a validated Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (DC/TMD) that would have widespread use in the clinical setting as well as in research.

This executive summary describes the evidence-based Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD), which is a dual-axis framework for the assessment and diagnosis of Axis I physical diagnoses for the most common TMDs and Axis II self-report psychosocial and behavioral screening questionnaires. This summary is based on Schiffman et al, Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. That document should be consulted for full discussion and references.8

Methods

Between 2008 and 2011, a series of symposia and workshops refined the Axis I diagnostic criteria for the most common TMD. In 2011–2012, the Axis I protocol underwent field trials regarding examiner specifications and Axis I and II self-report questionnaires. Throughout this process, the Validation Project’s dataset, including gold standard diagnoses, was used to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the recommended DC/TMD Axis I physical diagnoses. A detailed description of the above process is available.9 The resultant DC/TMD taxonomy was subsequently published in 2014.8

Recommendations

Axis I: Physical assessments

Axis I Screening Questionnaire. The TMD Pain Screener is a reliable and valid 6-item questionnaire to assess for pain-related TMD.10 Given the potential for dental treatments to precipitate TMD or aggravate pre-exiting TMD and the importance of early diagnosis and treatment to prevent chronicity, the routine use of this questionnaire is indicated in most dental settings. This questionnaire assesses the report of pain and factors that may affect the pain, including jaw movement, function, and parafunction.

-

Axis I Physical diagnoses. Tables 1 and 2 present the validated history and examination criteria for Axis I diagnoses and estimates of the criterion validity (sensitivity, specificity) for the most common TMD. Acceptable diagnostic accuracy is sensitivity ≥ 70% and specificity ≥ 95%.1 The diagnostic algorithms for myalgia, myofascial pain with referral, and arthralgia have acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity for a definitive diagnosis. Local myalgia and myofascial pain are additional subtypes of myalgia, and while they have content validity they have not yet been assessed for criterion validity using a credible gold standard. The diagnostic accuracy of headache attributed to TMD has adequate sensitivity with slightly below-target specificity, and is nevertheless recommended for clinical use.

All but one of the diagnostic algorithms for TMJ intra-articular disorders has diagnostic accuracy below the targets for sensitivity and/or specificity and therefore can only be used for screening purposes to render preliminary diagnoses of disk displacements (DD) or degenerative joint disease (DJD). The only exception is DD without reduction with limited opening (sensitivity of 0.80 and specificity of 0.97). Subluxation is based on history and has acceptable diagnostic validity for clinical use.8

Axis I Physical assessment tools. All diagnostic tools are available on the Consortium website and may be downloaded and used without copyright infringement.10 The DC/TMD Symptom Questionnaire (DC/TMD SQ) is recommended for history taking to collect the data pertinent for specific DC/TMD Axis I diagnoses. The DC/TMD clinical examination data collection form is available for both US and international settings that use the FDI tooth numbering system. Clinical examination specifications and decision trees for TMD pain diagnoses and intra-articular (joint) diagnoses are available.

Table 1.

Validated Axis I Pain-Related TMD Diagnoses

| DISORDER | HISTORY | EXAM FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

|

Myalgia* Sens: 90% Spec: 99% |

Pain in a masticatory structure modified by jaw movement, function, or parafunction. | Report of familiar pain** in temporalis or masseter muscle(s) with:

|

|

Myofascial Pain with Referral Sens: 86% Spec: 98% |

Same as for Myalgia. |

|

|

Arthralgia Sens: 89% Spec: 98% |

Same as for Myalgia. | Report of familiar pain** in TMJ with:

|

|

Headache Attributed to TMD Sens: 89% Spec: 87% |

Headache in temporal area modified by jaw movement, function, or parafunction. | Report of familiar headache*** in temple area with:

|

Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity

Myalgia can be sub-classified into 3 disorders: local myalgia, myofascial pain, and myofascial pain with referral; only myofascial pain with referral has been validated. See Schiffman et al, 2014, for diagnostic criteria for local myalgia and myofascial pain.

Familiar pain is similar or like the pain the patient has been experiencing. The intent is to replicate the patient’s pain complaint.

Familiar headache is similar or like the headache the patient has been experiencing. The intent is to replicate the patient’s headache complaint.

Table 2.

Validated Axis I TMJ Diagnoses

| DISORDER | HISTORY | EXAM FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

|

Disc Displacement with Reduction Sens: 34% Spec: 92% |

TMJ noise(s) present. | Clicking, popping or snapping noise present with:

|

|

Disc Displacement with Reduction with Intermittent Locking Sens: 38% Spec: 98% |

|

Same as Disc Displacement with Reduction. Note: When disorder is present in clinic, maneuver is required to open mouth. |

|

Disc Displacement without Reduction with Limited Opening Sens: 80% Spec: 97% |

|

Maximum assisted opening (passive stretch) < 40mm. Note: Maximum opening includes inter-incisal opening + vertical overlap of incisors. |

|

Disc Displacement without Reduction without Limited Opening Sens: 54% Spec: 79% |

|

Maximum assisted opening (passive stretch) ≥ 40mm. Note: Maximum opening includes inter-incisal opening + vertical overlap of incisors |

|

Degenerative Joint Disease Sens: 55% Spec: 61% |

TMJ noise(s) present. | Crepitus * present during maximum active opening, passive opening, right lateral, left lateral or protrusive movement(s). Note: Crepitus is defined as crunching, grinding, or grating noise(s). |

|

Subluxation Sens: 98% Spec: 100% |

TMJ locking or catching in a wide open position that resolves with a specific maneuver (e.g., moving the jaw). | Note: When disorder is present in clinic, maneuver is required to close mouth. |

Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity

Axis II: Psychosocial and behavioral assessment

Five Axis II questionnaires are recommended as screening tools for routine assessment of psychosocial and behavioral factors that may impact on patients’ response to treatment (Table 3). These instruments include the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS),11, 12 Pain Drawing,10 Jaw Functional Limitation Scale (JFLS),13 Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4),14, 15 and Oral Behaviors Checklist (OBC).16–18 The role of each instrument is described further below. Additional Axis II instruments are available for more comprehensive assessments (Table 3).

Table 3. Axis II assessment protocol.

Questionnaires to assist in the identification of patients with a range of simple to complex presentations that affect treatment and prognosis

| Questionnaires | # items | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS)1, 2 | 7 | Pain intensity component: pain amplification and central sensitization Pain-related disability component: decreased functioning due to pain |

| Pain drawing1, 2 | 1 | Distinguishes between local, regional, and widespread pain; assesses for other co-morbid pain condition; may indicate pain amplification, sensitization, and central dysregulation |

| Jaw Functional Limitation Scale (JFLS)1, 2 | 8 or 20 | Quantifies impact on jaw mobility, mastication, and verbal and emotional expression |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4)1 | 4 | Identifies psychological distress (depression and anxiety) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)2 | 9 | Identifies depression: contributes to chronicity |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)2 | 7 | Identifies anxiety: contributes to stress reactivity and to parafunction |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15)2 | 15 | Measures physical symptoms: assess for specific co-morbid functional disorders |

| Oral Behaviors Checklist (OBC)1, 2 | 21 | Measures parafunction: contributes to onset and perpetuation of pain |

Questionnaire included in screening protocol.

Questionnaire included in comprehensive protocol.

Clinical Application

The TMD Pain Screener is recommended for routine screening for pain-related TMD. It identifies patients who have a pain-related TMD and may be in need of treatment. It also identifies patients at risk for exacerbating their pre-existing pain during dental treatments. Having this documentation provides the opportunity to inform the patient about any TMD symptoms that may occur during treatments such as with long procedures, when a significant force is placed on the jaw, or with wide opening of the mouth. With this information the dentist can take appropriate precautions to protect the patient’s jaw including any combination of shorter appointments, frequent breaks, early termination of treatment, or supporting the patient’s jaw during treatment. The TMD Pain Screener, by identifying patients with pain-related TMD, facilitates informed consent by the clinician regarding potential complications from dental treatment.

Rendering Axis I diagnoses

When using the Axis I diagnoses, the clinician must first rule out odontogenic pathology and other pain disorders that can occur in the masticatory system. Numbness, swelling and/or redness are typically not present with the common TMDs and when present significant pathologies including infections, neoplasms and systemic conditions need to be ruled out. In addition, the uncommon TMDs must also be considered (Table 4).19

Table 4.

Taxonomic Classification for Temporomandibular Disorders

| I. TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT DISORDERS |

1. Joint pain

|

2. Joint disorders

|

3. Joint diseases

|

| 4. Fractures |

5. Congenital/developmental disorders

|

| II. MASTICATORY MUSCLE DISORDERS |

1. Muscle pain

|

| 2. Contracture |

| 3. Hypertrophy |

| 4. Neoplasm |

5. Movement Disorders

|

6. Masticatory muscle pain attributed to systemic/central pain disorders

|

| III. Headache |

| 1. Headache attributed to TMD |

| IV. Associated structures |

| 1. Coronoid hyperplasia |

For pain-related TMD, the patient must report that the pain or headache is located in the jaw or temple area(s), and that the pain or headache is modified (made better or worse) with jaw movement, function or parafunction. The DC/TMD Symptom Questionnaire (DC/TMD SQ) enables the collection of this information. During the clinical examination, the patient’s pain complaint(s) must be replicated during palpation or range of motion of the jaw by having the patient report “familiar pain” or “familiar headache” with these provocation tests. Familiar pain is similar or like the pain they are complaining about. Replication minimizes the false positives from the provocation tests with asymptomatic patients. It also allows the clinician to ascertain whether provoked pain is relevant to the patient’s pain complaint and not an incidental finding. It is often sufficient for the clinician to characterize the patient’s pain-related TMD as arthralgia and/or myalgia. However, assessing for myofascial pain with referral is useful in cases of non-odontogenic “tooth” pain since jaw muscles can refer pain to the teeth.20–22

The diagnostic criteria for myalgia, and its subtypes, only require palpation of the masseter and temporalis muscles as the minimum. However, examination of the other masticatory muscles may be indicated especially when the patient’s pain complaint(s) have not been replicated by the standard examination. These additional muscles were not included in these diagnostic criteria since the muscles are difficult to palpate, their positive findings for pain were not shown to improve overall the validity of pain diagnoses, and palpation results from these muscles have poor reliability.23–25 Similarly, for arthralgia, palpation of the TMJ involves examination only of the lateral aspect of the joint. Other adjunctive tests such as a TMJ compression test may be indicated in certain clinical situations.

The diagnostic criteria for TMJ intra-articular disorders, with the exception of DD without reduction with limited opening, can only be used for screening purposes due to inadequate criterion validity. Definitive diagnoses require TMJ MRI for DD and TMJ CT for DJD. Taking as an example the diagnosis of DD with reduction, the clinical criteria for this diagnosis have low sensitivity but high specificity relative to findings from TMJ MRI. This means that a clinician may be relatively confident of this diagnosis in the presence of TMJ clicking, popping or snapping noises that meet the criteria for this disorder. Conversely, the absence of joint noises does not rule out a diagnosis of DD with reduction. Many patients with MRI-depicted DD with reduction do not have any clinically detectable joint noise or have only sporadic occurrence of these noises, which is why the diagnostic criteria for this disorder have low sensitivity. In contrast, the diagnostic criteria for DD without reduction with limited opening have sufficient validity (sensitivity = 80% and specificity = 97%) but caution is still recommended. Certainty for this diagnosis requires MRI since these diagnostic criteria have not been assessed for criterion validity in patients with other disorders that result in limited opening.3 In the past, the criteria for DD without reduction included other findings such as deviation with opening to the affected side, but these findings are not consistently present and thus were not included. As for DD without reduction without limited opening and DJD, their respective history and clinical criteria are not sufficient to establish these diagnoses without recourse to imaging. DD with reduction without limited opening has poor diagnostic validity because many of these patients do not endorse a history of limited opening sufficient to interfere with eating, and appear to be clinically normal (i.e., no joint noise and no limitation with jaw movements).5 As for DJD, crepitus can occur without frank osseous changes and crepitus is not always present with DJD.

MRI is an excellent imaging technique for DD and joint effusions, but the sensitivity for detecting DJD is only 59% when CT is used as the gold standard.26 Thus CT is needed to accurately assess for DJD in order to address the false negatives that occur when using MRI. Finally, panoramic radiographs are typically available in dental offices. However, these radiographs have a sensitivity of 26% for detecting DJD compared to CT and thus have a substantial number of false negatives.26

Using Axis I criteria allows for a preliminary or “working” intra-articular diagnosis, and imaging can therefore be deferred. However, when the patient has significant mechanical problems, when significant pathology is suspected, or when TMD treatment has been unsuccessful at addressing the patient’s complaints, then imaging is indicated.

Assessment of the Occlusion

Occlusal findings did not improve the validity of the Axis I diagnostic criteria. However, routine occlusal assessment is recommended because occlusal status may change with treatment. Also, TMD can cause transient or persistent malocclusions. For example, with unilateral arthralgia, if an effusion (e.g., swelling) is present, an ipsilateral posterior open bite can be present19 or with bilateral DJD, an anterior open bite may occur.19 Therefore, clinically significant occlusal findings should be documented.

Axis II: Psychosocial and Behavioral Factors

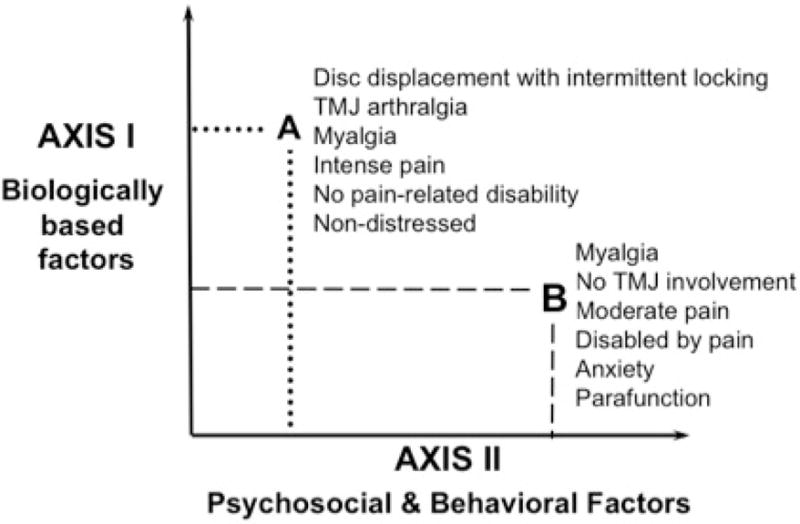

A dual axis protocol allows for assessing the whole person; compared to Axis I physical diagnoses for the common TMDs, Axis II contributing factors currently have better prognostic value.27–30 Pain involves both sensory and emotional experiences.31, 32 Axis I addresses the neurosensory input from peripheral tissues. However, pain as an experience is modulated by activity in multiple areas of the central nervous system (CNS), and consequently the whole person needs to be assessed. The Axis II protocol is based on the biopsychosocial model that characterizes pain as being expressed and intensified by Axis II factors to varying degrees beyond biological factors such as joint limitations and local inflammation. The Axis II effects include cognitive, psychosocial and behavioral factors that can additionally complicate treatment outcome and contribute to chronicity.27, 28 Figure 1 illustrates how the array of Axes I and II factors in the biopsychosocial model distinguish patients with a range of simple to complex TMD presentations who need very different treatments.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial model of disease applied to TMD.

For screening purposes, selected contributing factors were targeted in the Axis II questionnaires. If these potential contributing factors are present, then the clinician needs to assess these further, or refer the patient to a mental health professional for a comprehensive assessment that should then be included in the treatment plan. Conversely, the clinician can use these screening questionnaires to triage the patient and, when significant findings are present, refer the patient to clinicians with more expertise rather than initiate treatment that may have a high risk of failure. If referral is not an option, then the clinician can explain the challenges that exist and that complete resolution of pain may not be possible. In this way the patient receives comprehensive informed consent regarding the potential contributing factors to their complaints before treatment is initiated.

Relative to the recommended Axis II questionnaires, the PHQ-4 assesses for psychological distress including features of anxiety and depression, which can complicate treatment outcomes. If the patient has elevated scores on the PHQ-4, then further assessment for psychological conditions is indicated. The more comprehensive approach for assessment of distress utilizes the PHQ-933 for depressive symptoms and the GAD-734, 35 for anxiety symptoms in lieu of using the PHQ-4. The gold standard for diagnosing psychological distress is an assessment by a mental health professional, ideally, a health psychologist when pain is an issue.

The GCPS assesses both pain intensity and pain-related disability regarding the degree the pain interferes with the patient’s life. High levels of pain suggest the need to first rule out significant pathology but may indicate that the patient has amplification of symptoms due to emotional distress and/or central sensitization. The JFLS, as a measure specific to the masticatory system, assesses functional limitation and complements the findings from the GCPS. The JFLS has a short form for global assessment of patient-reported ability to use the jaw for mastication, mobility, and other functions, and a long form that can group the findings into three constructs: mastication, mobility, and emotional and verbal expression.

The pain drawing10 assesses for local, regional or widespread pain. Local pain is limited to the masticatory area and regional pain often is present since many patients with TMD also have concurrent cervical conditions. When cervical pain is present, then medical assessment, including evaluation by a physician or physical therapist, can be considered. Widespread pain throughout the body is suggestive of systemic pain disorders such as rheumatic diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. When widespread pain is present, assessment of the systemic condition may be needed in order to have a significant impact on the “local” TMD. However, widespread and multiple bodily complaints may indicate that the patient has amplification of their pain from central sensitization and dysregulation, and these patients need multidisciplinary treatment teams. The pain drawing can be accompanied by the PHQ-1536 for more quantitative assessment of possible presence and severity of co-morbid disorders.

Finally, comprehensive assessment of parafunctional behaviors (e.g., oral habits) is important since they can overload the masticatory structures. The available evidence supports an often-expressed clinical suspicion that such behaviors can cause or perpetuate the patient’s pain.37–42 When the patient is aware of these behaviors but cannot control them, especially habits present during awakening, other factors such as underlying stress reactivity (e.g., autonomic arousal) or anxiety are generally present, and further assessment is needed. It is noteworthy that oral behaviors have been shown to be associated with both the onset of TMD pain and development of chronic TMD pain.43, 44

Conclusion

The new evidence-based DC/TMD recommendations allow for identification of patients with a range of simple to complex TMD presentations. The DC/TMD is appropriate for use in the clinical and research settings. The DC/TMD provides a common language for clinicians and researchers. Clinical observations using the DC/TMD can be the basis for future research. Conversely, research findings can be directly applied to the clinical setting. To facilitate this, the Axis I history questionnaire and exam forms as well as all Axis II assessment questionnaires are available via the internet with no copyright restrictions.10 Future research will lead to diagnostic protocols based on etiology and mechanisms to allow for more targeted, personalized treatment plans for the patients we serve.

Acknowledgments

The co-authors of the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group were, in order of authorship, Ed Truelove DDS, MS; John Look, DDS, PhD; Gary Anderson, DDS, MS; Sharon L Brooks, DDS, MS; Werner Ceusters, MD; Mark Drangsholt, DDS, PhD; Samuel F Dworkin, DDS PhD; Dominik Ettlin, MD, DDS; Charly Gaul, MD; Yoly Gonzalez, DDS, MS, MPH; Louis J Goldberg, DDS, PhD; Jean-Paul Goulet, DDS, MSD; Jennifer A Haythornthwaite, PhD; Lars Hollender, DDS, Odont Dr; Rigmor Jensen, MD, PhD; Mike T John, DDS, PhD; Antoon deLaat, DDS, PhD; Reny deLeeuw, DDS, PhD; Thomas List, DDS, Odont Dr; Frank Lobbezoo, DDS, PhD; William Maixner, DDS, PhD; Marylee van der Meulen, PhD; Ambra Michelotti, DDS; Greg M Murray, MDS, PhD; Donald R Nixdorf, DDS, MS; Sandro Palla, DDS; Arne Petersson, DDS, Odont Dr; Paul Pionchon, DDS, PhD; Barry Smith, PhD; Peter Svensson, DDS, PhD, Dr Odont; Corine M Visscher PT, PhD; Joanna Zakrzewska, BDS, MD; FDSRCSI and Samuel Dworkin DDS, PhD.

These individuals consisted of members of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network of the International Association for Dental Research; Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group of the International Association for the Study of Pain; American Academy of Orofacial Pain; European Academy of Craniomandibular Disorders; OPPERA; International Headache Society; National Center for Ontological Research; and RDC/TMD Validation Project.

Research performed by the Validation Project Research Group was supported by NIH/NIDCR U01-DE013331. The development of the examination specifications in support of the diagnostic criteria was also supported by NIH/NIDCR U01-DE017018 and U01-DE019784. Reliability assessment of Axis I diagnoses was supported by U01-DE019784. Workshop support was provided by the International Association for Dental Research, Canadian Institute for Health Research, International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, Medotech, National Center for Biomedical Ontology, Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group of the International Association for the Study of Pain, and Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. The authors thank the American Academy of Orofacial Pain for their support; and Terrie Cowley, president of the TMJ Association, for her participation in the Miami workshop.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Based on the publication: Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network** and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group***

IADR

IASP

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Contributor Information

Eric Schiffman, Department of Diagnostic and Biological Sciences, University of Minnesota.

Richard Ohrbach, Department of Oral Diagnostic Sciences, University at Buffalo.

References

- 1.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: Review, Criteria, Examinations and Specifications, Critique. Journal of Craniomandibular Disorders, Facial and Oral Pain. 1992;6(4):301–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fillingim RB, Bruehl S, Dworkin RH, et al. The ACTTION-American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy (AAPT): An evidence-based and multidimensional approach to classifying chronic pain conditions. Journal of Pain. 2014;15(3):241–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bossuyt PM, Reistsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. Toward complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. Clinical Chemistry. 2009;49:1–6. doi: 10.1373/49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truelove E, Pan W, Look JO, et al. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. III: Validity of Axis I diagnoses. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 2010;24(1):35–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiffman EL, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, et al. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. V: Methods used to establish and validate revised Axis I diagnostic algorithms. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 2010;24(1):63–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohrbach R, Turner JA, Sherman JJ, et al. Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. IV: Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of the Axis II Measures. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 2010;24:48–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson GC, Gonzalez YM, Ohrbach R, et al. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. VI: Future Directions. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 2010;24:79–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache. 2014;28(1):6–27. doi: 10.11607/jop.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohrbach R. Development of the DC/TMD: A brief outline of major steps leading to the published protocol. International RDC/TMD Consortium Network: 2014. http://www.webcitation.org/6dBv3NAKI. Accessed November 23, 2015.

- 10.Ohrbach R, editor. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. Complete Instrument Set. International RDC/TMD Consortium Network: 2014. 2014 http://www.webcitation.org/6dBvdLXj7. Accessed November 23, 2015.

- 11.Von Korff M. Assessment of chronic pain in epidemiological and health services research: Empirical bases and new directions. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 3rd. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 455–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133–49. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohrbach R, Larsson P, List T. The Jaw Functional Limitation Scale: Development, reliability, and validity of 8-item and 20-item versions. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 2008;22:219–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionaire-4 in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markiewicz MR, Ohrbach R, McCall WD., Jr Oral Behaviors Checklist: Reliability of Performance in Targeted Waking-state Behaviors. Journal of Orofacial Pain. 2006;20(4):306–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohrbach R, Markiewicz MR, McCall WD., Jr Waking-state oral parafunctional behaviors: specificity and validity as assessed by electromyography. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2008;116(5):438–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan SEF. Ohrbach R. Self-report of waking-state oral parafunctional behaviors in teh natural environment. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache In review. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peck CC, Goulet J-P, Lobbezoo F, et al. Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2014;41(1):2–23. doi: 10.1111/joor.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: the Trigger Point Manual. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sessle B. Acute and chronic craniofacial pain: brainstem mechanisms of nociceptive transmission and neuroplasticity, and their clinical correlates. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2000;11:57–91. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152:S2–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turp JC, Minagi S. Palpation of the lateral pterygoid region in TMD – where is the evidence? Journal of Dentistry. 2001;29:475–83. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(01)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnstone DR, Templeton M. The feasibility of palpating the lateral pterygoid muscle. J Prosthet Dent. 1980;44:318–23. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(80)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conti P, Dos Santos Silva R, Rossetti L, et al. Palpation of the lateral pterygoid area in the myofascial pain diagnosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e61–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad M, Hollender L, Anderson Q, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD): development of image analysis criteria and examiner reliability for image analysis. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology Endodontology. 2009;107:844–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epker J, Gatchel RJ, Ellis EI. A model for predicting chronic TMD: Practical application in clinical settings. JADA. 1999;130:1470–75. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garofalo JP, Gatchel RJ, Wesley AL, Ellis EI. Predicting chronicity in acute temporomandibular joint disorders using the Research Diagnostic Criteria. JADA. 1998;129:438–47. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatchel RJ. A biopsychosocial overview of pretreatment screening of patients with pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2001;17(3):192–99. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatchel RJ, Stowell AW, WIldenstein L, Riggs R, Ellis EI. Efficacy of an early intervention for patients with acute temporomandibular disorder-related pain: a one-year outcome study. JADA. 2006;137:339–47. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gracely RH. Subjective Quantification of Pain Perception. In: Bromm B, editor. Pain Measurement in Man. Neurophysiological Correlates of Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishers; 1984. pp. 371–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price DD, Barrell JJ, Gracely RH. A psychophysical analysis of experiential factors that selectively influence the affective dimension of pain. Pain. 1980;8:137–49. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care. 2008;46(3):266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–97. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(2):258–66. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glaros AG. Temporomandibular disorders and facial pain: a psychophysiological perspective. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback. 2008;33(3):161–71. doi: 10.1007/s10484-008-9059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glaros AG, Williams K, Lausten L. The role of parafunctions, emotions and stress in predicting facial pain. JADA. 2005;136:451–58. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gavish A, Halachmi M, Winocur E, Gazit E. Oral habits and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescent girls. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2000;27(1):22–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2000.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glaros AG, Burton E. Parafunctional clenching, pain, and effort in temporomandibular disorders. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27(1):91–100. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000013646.04624.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michelotti A, Cioffi I, Festa P, Scala G, Farella M. Oral parafunctions as risk factors for diagnostic TMD subgroups. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2010;37(3):157–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nilner M. Relationships between oral parafunctions and functional disturbances in the stomatognathic system among 15- to 18-year-olds. Acta Odontol Scand. 1983;198:197–201. doi: 10.3109/00016358309162324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohrbach R, Bair E, Fillingim RB, et al. Clinical orofacial characteristics associated with risk of first-onset TMD: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. Journal of Pain. 2013;14(12):T33–T50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.07.018. (Supplement 2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohrbach R, Fillingim RB, Mulkey F, et al. Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: Descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. Journal of Pain. 2011;12(11, Supplement 3):T27–T45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]