Abstract

Although adaptive meanings of childhood maltreatment (CM) are critical to posttraumatic adaptation, little is known about perceptions of posttraumatic change (PTC) during the vulnerable postpartum period. PTC may be positive or negative as well as global or situational. This study examined general and parenting-specific PTC among 100 postpartum women with CM histories (Mage = 29.5 years). All reported general and 83% reported parenting PTC. General PTC were more likely to include negative and positive changes; parenting PTC were more likely to be exclusively positive. Indicators of more severe CM (parent perpetrator, more CM experiences) were related to parenting but not general PTC. Concurrent demographic risk moderated associations between number of CM experiences and positive parenting PTC such that among mothers with more CM experiences, demographic risk was associated with stronger positive parenting PTC. Results highlight the significance of valence and specificity of PTC for understanding meanings made of CM experiences.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Postpartum, Mothers, Meaning making, Posttraumatic growth, Posttraumatic change

1. Introduction

Making meaning of childhood maltreatment (CM) experiences can result in altered views of the self, others, relationships, and the world (Janoff-Bulman, 1995; Joseph & Linley, 2005; Park, 2010), which we collectively refer to as posttraumatic changes (PTC; Simon, Smith, Fava, & Feiring, 2015). Although adaptive meanings of CM are crucial to posttraumatic adaptation (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006; Collins & Laursen, 2004), perceptions of maltreatment-related PTC may be positive (e.g., enhanced personal strength) or negative (e.g., viewing others as untrustworthy). Moreover, PTC are open to modification across developmental and life experiences (Harvey, Mishler, Koenen, & Harney, 2000). The current study examines PTC during the transition to motherhood, a time when many revisit their childhood maltreatment experiences (Seng et al., 2013).

Relatively little is known about how new parents perceive the changes experienced in relation to CM. Prior work demonstrates that adolescents and young adults with CM histories experience PTCs in their general views of the self, others, and world as well and that these changes are related to psychosocial adjustment (Simon et al., 2015). The current study adds to this work by examining PTC that are specific to parenting. How mothers view themselves as parents or their parenting has implications for parenting behavior and the quality of parent–child relationships. Mothers with CM histories may lack confidence in their abilities to regulate their emotions within their relationship with their child (Cole, Woolger, Power, & Smith, 1992), be a good parent, or experience the parent–child relationship positively (Milan, Lewis, Ethier, Kershaw, & Ickovics, 2005). On the other hand, some mothers perceive prior CM experiences as lessons for positive parenting, even in the face of negative changes in general core views (Wright, Crawford, & Sebastian, 2007). By articulating the nature of new mothers’ general and parenting-specific PTC, we sought to identify the types of PTC most salient to postpartum mothers with CM histories. Such information can provide important insights about how mothers process CM experiences and potential intervention targets for this vulnerable population.

1.1. The development of posttraumatic changes (PTC)

Posttraumatic changes are alterations in views of the self, relationships, or world that result from efforts to make meaning of CM experiences (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Joseph & Linley, 2005; Park, 2010; Simon et al., 2015). Such changes may be either positive or negative. Examples of positive changes include perceptions of improved personal strength, coping, and ability to protect oneself from danger (changes in views of self); of increased intimacy, empathy, and support (changes in relationship views), or of greater appreciation for life, increased spirituality, and enhanced sense of purpose (changes in world views; Easton, Coohey, Rhodes, & Moorthy, 2013; McMillen, Zuravin, & Rideout, 1995; Shakespeare-Finch & de Dassel, 2009; Wright et al., 2007). However, CM may also challenge core beliefs in ways that lead to perceptions of negative change in the self (e.g., being unworthy of love), relationships (e.g., others are untrustworthy), or the world (e.g., the world is unjust; Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Joseph & Linley, 2005).

To date, research on PTC has focused on positive change (e.g., posttraumatic growth) with little attention to perceptions of negative change or the co-occurrence of positive and negative changes. A handful of studies suggest that many youth and adults report both growth and costs from CM experiences (McMillen et al., 1995; Simon et al., 2015). For instance, one might experience increased personal strength but also negative changes in trust of relationship partners. In a study of youth with sexual abuse histories, participants reported more negative than positive PTCs, but approximately half reported both positive and negative changes (Simon et al., 2015). Further, youths’ perceptions of positive and negative PTC showed unique relations with psychosocial adjustment. The current study extends prior work focused on sexual abuse to articulate the co-occurring positive and negative changes experienced by women during the transition to motherhood.

1.2. The transition to motherhood and meanings made of childhood experiences

Reflecting upon one’s own childhood and experiences of being parented is common during the transition to motherhood (Cohen and Slade, 1999; Stern, 1995). For women with CM histories, revisiting these experiences might prompt renewed consideration of the meanings of these experiences for general as well as parenting specific views of the self, relationships, and world. Such contemplation might provide an opportunity to restore meaning in life, or renew hopefulness but might also raise concerns about oneself as a competent parent, the parent–child relationship, or more general views about parenting (Banyard, 1997; Seltmann & Wright, 2013; Seng et al., 2013; Wright, Fopma-Loy, & Oberle, 2012). In this way, CM may shape both general and parenting-specific models of the self, others, and the world (Park, 2010). Yet, we know very little about parenting-specific PTC among new mothers with histories of CM, including the extent to which parenting PTC mirror more general changes in the self, relationships, or world views.

In one of few studies to examine mothers’ meaning-making of CM, roughly half of the mothers surveyed reported some perceived benefit from their abuse experience (Wright et al., 2007). The most frequently reported gains were in coping skills (43%), relationships (37%), and parenting skills (30%). However, when asked to specify meanings made from the abuse, 29% of mothers were unable to give any response or identify any meaning, suggesting that such direct queries in a survey format may be difficult. Of those who responded, 19% reported a mix of positive and negative meanings. No mothers reported negative meanings related to parenting; however, about 32% reported negative changes in views of the self, relationships, or the world.

The current study adds to this literature by examining general and parenting-specific perceptions of positive and negative changes among new mothers with histories of various forms of CM (i.e., physical, sexual, emotional abuse or neglect). Consistent with prior work, we assessed perceptions of PTC using a semi-structured interview that inquires about maltreatment experiences, reactions, and effects over time. Narratives are uniquely suited for studying how individuals make meaning of traumatic experiences because they provide a window into speakers’ internalized life stories (McAdams and McClean, 2013). When freely relating their CM experiences, individuals reveal the heart of meaning making - the constructive process by which they evaluate past CM experiences in light of current conditions (Riessman, 1993; Singer, 2004). For the current study, the narratives were used to assess the strength and valence of both general and parenting PTCs. Although general PTCs appear to be present as early as adolescence (Simon et al., 2015), parenting PTC may not be known or internalized before motherhood, at which time mothers more seriously contemplate the meanings of CM experiences for emergent views of themselves as parents. Thus, one aim of the current study was to articulate the frequency and valence of new mothers’ general and parenting PTC.

1.3. Maltreatment characteristics and demographic factors in relation to mothers’ PTC

A second study aim was to examine whether maltreatment characteristics or concurrent demographic risk was related to PTC. Regarding maltreatment characteristics, research by Finkelhor and colleagues suggest that the number of maltreatment types experienced is a significant predictor of poor adaptation, with only sexual abuse conferring unique risk among the various types of CM (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). Similarly, work by Newcomb and Locke (2001) suggests that sexual abuse exerts unique effects on parenting above and beyond other forms of victimization. Accordingly, we expected that experiencing more types of CM and a history of sexual abuse would each be associated with stronger negative general and parenting PTC. Further, maltreatment perpetrated by caregivers is believed to be especially insidious to the development of healthy working models of self and relationships, because the person the child relied on for care also became a source of fear or pain (Kobak, Cassidy, Lyons-Ruth, & Zir, 2006). Thus, we anticipated that CM perpetrated by a parent figure might be especially meaningful to new mothers and related to stronger negative parenting PTC.

Demographic characteristics, including older age, higher educational attainment, higher income and being married have been associated with stronger perceptions of posttraumatic growth or positive PTC (Shakespeare-Finch & de Dassel, 2009). However, individuals with CM histories are more likely to experience demographic risks (e.g., single parenthood, poverty) that are associated with parenting difficulties (Lipman et al., 2001). Accordingly, we expected that fewer indicators of current demographic risk would be associated with stronger positive and weaker negative PTCs in both general and parent-specific domains. Considering the intersection of past and present risks, we anticipated that a history of more severe CM might amplify the associations between demographic risk and negative posttraumatic change.

1.4. Current study

The goal of the current study was to describe postpartum women’s perceptions of PTC in connection with their CM experiences. We were interested in the co-occurrence of positive and negative PTC as well as whether general changes in views of the self, relationship, and world mirrored parenting-specific PTC. In addition, we wanted to know whether maltreatment characteristics or concurrent demographic risk were related to these changes. Extant work suggests that PTC is complex in valence and specificity. Articulating the dimensions of PTC during the transition to motherhood may shed light on dimensions of trauma processing that could shape maternal and child well-being.

Our primary hypotheses related to general PTC were: 1) most mothers would report some form of general PTC; 2) mothers would be more likely to report co-occurring positive and negative PTCs than either positive-only or negative-only PTC; 3) lower demographic risk and fewer CM experiences would each be related to stronger positive PTC, and; 4) higher levels of current demographic risk, maltreatment by a parent figure, more CM experiences, and a history of sexual abuse would each be related to reports of more negative PTC. Secondarily, we hypothesized that demographic risk would moderate the relation between CM characteristics and general PTC, such that negative general PTC would be strongest among mothers with more severe CM (parent-perpetrated, more events) and higher levels of postpartum demographic risk.

Although studies of parenting PTC are few, our prior work and the broader literature on CM and parenting suggested that: 1) almost all mothers would report some form of parenting PTC; 2) reports of positive or mixed valence parenting PTC would be more common than negative-only PTC; 3) older age, lower demographic risk, and fewer CM experiences would each be related to stronger positive PTC, and; 4) higher levels of current demographic risk, maltreatment by a parent figure, more CM experiences, and a history of sexual abuse would each be related to reports of more negative PTC. As with general PTC, we believed demographic risk would moderate the relation between CM characteristics and parenting PTC, such that negative PTC would be strongest among mothers with more severe CM (parent-perpetrated, more events) and higher levels of postpartum demographic risk.

2. Method

2.1. Sample selection and characteristics

Participants for the current study were part of a larger, longitudinal study (N = 268) examining the effects of maternal childhood maltreatment on mothers’ and infants’ adjustment and parenting outcomes. Participants were recruited in one of two ways: as 4-month postpartum follow-up to a parent study on the prenatal effects of childhood maltreatment on childbearing (Seng, Kane Low, Sperlich, Ronis, & Liberzon, 2009), or through community advertisements in obstetric clinics, childbirth classes, and newspapers. All participants were English-speaking, non-psychiatrically referred women, aged 18 years and older, who were mothers of singleton births (i.e., they only gave birth to one child in this pregnancy). Exclusion criteria included diagnoses of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, active substance use problems within the last three months, and mothers of infants with severe health/developmental problems or more than six weeks premature. Data collection for the longitudinal study spanned from 4 to 18 months postpartum.

The study oversampled for women with CM histories, with over half the sample endorsing CM experiences (n = 170) on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ, Bernstein & Fink, 1998) that was administered at recruitment. The sample for the current study (n = 100) is restricted to women who reported a history of childhood maltreatment on the CTQ, completed the 4-months postpartum assessment, and completed an in-person trauma interview at 6-months postpartum. This interview was added after the larger study was initiated, therefore the number of women who completed the interview is lower than the full sample. The majority of the sample was married (67%), and 23% were not partnered. Sixty-five percent of mothers identified as White, 21% as African American, 6% as Asian or Pacific Islander, 3% as Latina, and 4% as biracial or other ethnicity. With respect to education, 64% had completed a college or technical degree, 25% reported some college, 6% completed high school/GED, and 5% did not complete high school/GED. Twenty-three percent of mothers reported a family income of less than $20,000, 28% between $20,000 and $50,000, and 49% at $50,000 or greater. Demographic characteristics of this subsample of 100 women did not differ from those of the larger study sample. Most mothers in the current study reported multiple occurrences of maltreatment (M = 4.63, SD = 3.20; range = 1–15). When asked to identify their most difficult or challenging maltreatment experience, 40% endorsed emotional abuse/neglect, 31% sexual abuse, 21% physical abuse, and 8% physical neglect. When considering mothers’ collective maltreatment experiences, 69% reported maltreatment by a parent figure.

2.2. Procedure

The Institutional Review Boards of the sponsoring academic institutions approved all procedures. At 4 months postpartum, participants completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) by phone and agreed to complete two home-based assessments when their baby was 6 months old. During the first home visit mothers provided written consent for themselves and their infants to complete a series of infant-focused interactive tasks, interviews, and questionnaires. The current study focuses on data from the second home assessment, conducted 1–2 weeks later, which included two interviews about their CM experiences, the Trauma Meaning Making Interview (TMMI) and the Trauma History Table. Women were compensated $10 for the 4 months entry phone interview and a maximum of $130 for their participation in the overall longitudinal research.

2.3. Measures

Demographic risk

At 4-months postpartum, women provided their age, income, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education. Following prior work, we created a summary cumulative risk index (CRI; Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, & Baldwin, 1993). A point was assigned for each of the following dichotomized socio-demographic risk variables and then summed to create the CRI (possible and observed scores range from 0 to 5): non-White ethnic minority status, single parent status (i.e., unmarried or unpartnered), low education (i.e., less than a high school diploma or GED), low family income (i.e., less than $20,000 per year, which fell at or below the federal poverty line for most families in this sample), and young maternal age (i.e., less than 22 years old; α = .67).

Maltreatment characteristics

Detailed information about CM characteristics were assessed at 6 months postpartum using a Trauma History Table interview developed for this study. The Trauma Table included information about the type, frequency, duration, and perpetrator identity for any CM experienced prior to age 16 years. Information from this table was used to create three variables for the current analyses: 1) a cumulative count of lifetime maltreatment experiences; 2) a binary indicator of whether a participant experienced sexual abuse; and 3) a binary indicator of whether any maltreatment experiences had been perpetrated by a parent figure. The cumulative count of lifetime maltreatment experiences was derived by summing the number of discrete CM episodes perpetrated by the same or different individuals regardless of maltreatment type. For example, a participant who was sexually abused by two separate perpetrators at distinct times would receive a score of two as would a participant who was physically abused and neglected by the same perpetrator. The mean cumulative count for the current sample was 4.6 (SD = 3.2; range = 1–5) maltreatment episodes.

Posttraumatic change (PTC)

PTC was assessed from the semi-structured Trauma-Meaning Making Interview (TMMI; Simon, Feiring, & McElroy, 2010), which asks participants to describe their maltreatment; express their thoughts and feelings about the maltreatment and its discovery at the time it happened as well as over time; and to explain the perceived effects of their maltreatment experiences. For the current study, questions were added about the perceived impact of their CM experiences on becoming a parent and the parent–child relationship. Questions were open-ended and neutrally worded to allow participants to freely discuss either or both positive and negative aspects of CM experiences and their effects over time. An important quality of the narratives is that themes of PTC are not only queried directly (e.g., “How do you think these experiences have affected you?”; “Have your thoughts and feelings about the abuse changed over time?”) but also allowed to unfold naturally from participants’ accounts. Throughout the interview, participants were given time to consider their answers with verbal reassurance (e.g., “Take your time.”), provided re-wordings of questions, and followed up with “Anything else?” to ensure completeness of responses without prompting for specific material. Mothers who had reported more than one episode of child maltreatment on the CTQ or Trauma History Table, were asked to select and discuss the maltreatment experience they viewed as being most significant or impacting their lives the most. Interviews were audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy by a second person prior to coding.

Coding of PTCs

Trained coders reviewed each transcript for positive and negative PTCs. Positive and negative changes were coded separately for general and parenting views. General PTCs encompassed four domains: views of self (e.g., strength, competency), views of relationships (e.g., relationship seeking, intimacy), worldviews (e.g., safety, trust, fairness), and sexuality (e.g., sexual self-concept, sexual functioning). Parenting PTCs included three domains that mirrored their respective general domain: view of self as parent (self-view), parent–child relationship (views of relationships), and global views of parenting (world view). Coders noted the presence or absence of each type of positive and negative PTC across domains. Strength of change scores were assigned to PTCs on a 4-point scale (0–3), with higher scores indicating stronger changes. Scores of 1 were assigned to mentions of vague or weak change without indication of significant life impact. Scores of 2 were assigned to definitive statements of change illustrating a moderate life impact. Scores of 3, the highest rating possible, were assigned to definitive statements of change accompanied by evidence of strong life impact. Table 1 provides narrative examples of positive and negative general and parenting PTC at various strengths. Since questions were open-ended, not all participants responded about every domain; and those domains not mentioned were scored as zero. Coders were three research assistants trained to 80% reliability by the second author (who developed the interview) using transcripts from a different study. Reliability coding was completed by a second rater on 27% of the transcripts. Interclass correlations (ICCs) for general negative and positive PTC strength scores were α= .90 and α= 83. The ICCs for negative and positive parenting PTC strength scores were α= .71 and α= 86. Coding discrepancies of more than one point were resolved by consensus.

Table 1.

Narrative examples of PTC.

| Positive PTC | |

| General | “I guess that now I use it more as a tool to allow me to relate to other people. So that they can feel more comfortable with me and um possibly open up more about those situations, to help them feel supported.” (3) “I’m very open with myself and I’m very open with, um, sexuality, so like, I’m not homophobic that doesn’t bother me and I can comment on another girl’s saying that she’s gorgeous, she’s got a nice body.” (1) |

| Parenting- specific | “I can approach him differently than more [sic] parents would. You know, most parents would yell, scream. . .but since I’ve been there, that’s the last thing you want to do.” (3) “I think it’s taught me how to have an open relationship and want an open relationship with my child.” (3). |

| Negative PTC | |

| General | “I get, I am so angry now. Like I don’t know what it’s like I just I guess I have like a major anger issue or something.” (3) “Like our relationship between me and him, it’s affected because I don’t really, tell him everything.” (2) |

| Parenting- specific | “Umm getting angry and frustrated with my son, and not really having - I don’t really have my own coping mechanism so it’s really hard to teach him, um, self-control or self-soothing and things like that because I just have never really learned it myself.” (3) “Just being protective over her. . . I don’t know. Maybe when she gets older I might be too overprotective.” (1) |

Note. Strength of change is measured on a 4-point scale (0–3), with higher scores indicating stronger changes.

Data analytic strategy

Descriptive analyses were performed first to examine the frequency and strength of general and parenting PTCs and their bivariate relations with other study variables. Next, we conducted chi-square analyses to test for differences in the frequency of single valence versus co-occurring positive and negative PTC. Finally, associations between CM and demographic characteristics with PTC were examined in a series of regression models using the SAS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). The four dependent variables were positive and negative general and parenting PTC. Predictors in each regression included: whether or not a parent ever perpetrated any form of abuse, history of sexual abuse, number of CM experiences, and demographic risk. We tested both main and interaction effects of CM characteristics and demographic risk scores to assess whether greater current demographic risk moderated the associations between indicators of more severe CM and PTC. For models where the interactions were not significant, we present the results of reduced standardized models without the interaction terms. Significant interactions were probed using the Johnson-Newman (J-N) technique within the SAS PROCESS macro, which allows researchers to make inferences about the regions of significance of the effect of X on Y. The regions of significance indicate the point or points along the continuum of a quantitative moderator where the effect of the focal predictor transitions between statistical significance and non-significance. These points specify the range of values of the moderator where the effect of the focal predictor on the outcome is statistically significant and not significant. Unlike traditional “pick-point-approaches” (see Bauer & Curran, 2005) that require the researcher to select arbitrary values of the moderator at which the test the effect of the predictor (e.g., M ± 1SD), the J-N technique estimates the conditional effect of the independent variable across the observed distribution of the moderator.

Missing data

Analyses indicated that data was missing at random. Therefore, data were imputed using Expectation Maximization in IBM SPSS 21, which is of comparable accuracy to other imputation methods for data missing at random (Lin, 2010; Mu & Zhou, 2011). Reported results utilize the fully imputed dataset.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive information on PTC

All mothers (100%) endorsed some kind of general PTC, and they were more likely to report a mix of positive and negative PTC (75%), than negative-only (8%; χ2 (1) = 26.1, p < .001) or positive-only (17%; χ2 (1) = 61.4, p < .001) PTC. The majority of mothers reported some kind of parenting PTC (83%), with more reporting positive-only parenting PTCs (62%) than either a mix of positive and negative parenting PTC (19%) or negative-only parenting PTCs (2%; χ2 (1) = 26.1, p < .001).

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the various PTC strength scores, abuse characteristics, and demographic risk scores. The strength of positive and negative PTC were unrelated in both the general and parenting domains, supporting our view that positive and negative PTC are distinct. Further, of the four correlations between the general and parenting PTC scores, the only significant association was between negative general and negative parenting changes. Maltreatment by a parent figure was associated with stronger positive parenting PTC; and a history of sexual abuse was associated with weaker positive general PTC. A history of sexual abuse was also associated with more demographic risk.

Table 2.

Descriptive and bivariate correlations for main study variables.

| Main study variables | Mean | SD | Correlations

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 1. Demographic risk | 0.88 | 1.20 | – | |||||||

| 2. Number CM experiences | 4.60 | 3.20 | −.02 | – | ||||||

| 3. History of sexual abuse | 1.22 | 0.46 | .29** | .12 | – | |||||

| 4. Maltreatment by parent | 0.69 | 0.42 | .11 | −.23** | .36*** | – | ||||

| 5. Positive general PTC | 1.90 | 0.94 | −.21* | −.09 | −.23** | −.07 | – | |||

| 6. Negative general PTC | 1.90 | 1.10 | −.08 | .17 | .04 | −.08 | .10 | – | ||

| 7. Positive parenting PTC | 1.70 | 1.10 | −.15 | .07 | −.19† | −.25** | .13 | −.07 | – | |

| 8. Negative parenting PTC | 0.39 | 0.84 | −.05 | .23* | .03 | .01 | −.16 | .34*** | −.09 | – |

Note. Maltreatment by parent figure (0 = parent; 1 = non-parent). Sexual abuse (1 = no; 2 = yes).

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .07.

3.2. Associations of maltreatment and demographic characteristics with PTC

General PTC models

Table 3 presents the results from the two regressions predicting strength of general PTC (positive and negative) from CM characteristics and concurrent demographic risk. Contrary to expectations, neither CM characteristics nor demographic risk were directly related to general PTC; and demographic risk did not moderate associations between CM characteristics and PTC.

Table 3.

Results of standardized regression models predicting strength of negative and positive general PTCa.

| β Coefficient | SE | t | F (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative general PTC | ||||

| Intercept | −0.07 | .19 | −0.38 | |

| Maltreatment by parent | −0.16 | .27 | −0.59 | |

| History of sexual abuse | 0.15 | .25 | 0.62 | |

| Number of CM experiences | 0.14 | .11 | 1.32 | |

| Demographic risk | −0.09 | .11 | −0.85 | |

| Reduced Model | 0.95 (4, 95) | |||

| Positive general PTC | ||||

| Intercept | 0.27 | .18 | 1.45 | |

| Maltreatment by parent | −0.03 | .26 | −0.10 | |

| History of sexual abuse | −0.38 | .24 | −1.56 | |

| Number of CM experiences | −0.08 | .10 | −0.76 | |

| Demographic risk | −.16 | .10 | −1.52 | |

| Reduced Model | 2.11 (4, 95) | |||

Note:

Results are final models that include maltreatment by parent figure (0 = yes; 1 = no), lifetime experience of sexual abuse (experienced sexual abuse; 1 = no; 2 = yes), number CM experiences, and current demographic risk as covariates. If interaction terms were not significant, reduced models are presented excluding interactions.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Parenting PTC models

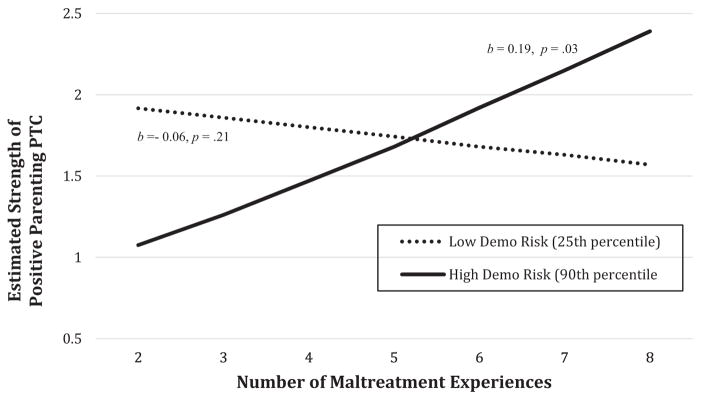

Table 4 presents the results from regressions predicting strength of parenting PTC (positive and negative) from CM characteristics and concurrent demographic risk. Number of CM experiences was the only significant predictor of negative parenting PTC, with more maltreatment experiences predicting stronger negative parenting PTC (β = .25, F [4,95] = 2.38, p < .05). The model predicting positive parenting PTC revealed a main effect for perpetrator identity, with parent-perpetrated CM being associated with stronger positive parenting PTC. The interaction between demographic risk and number of CM experiences was also significant (R2 = .13, F [5,94] = 2.84, p = .02). Fig. 1 illustrates the association between cumulative CM experiences and the strength of positive parenting PTC for participants at low (25th percentile) and high (90th percentile) levels of demographic risk. J-N analyses indicated that the conditional effect of number of CM experiences on the strength of positive parenting PTC became significant for mothers with demographic risk scores at and above 2.20 (89th percentile). For these mothers, more CM experiences were associated with stronger positive parenting PTC, [θ(X → Y)| M = 1.32 = .12, t(94) = 1.99, p = .05]. For mothers with demographic risk scores below 2.20, the number of CM experiences was unrelated to the strength of positive parenting PTC.

Table 4.

Results of standardized regression model predicting strength of negative and positive parenting PTCa.

| β Coefficient | SE | t | F (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative parenting PTC | ||||

| Intercept | −0.02 | .18 | −0.12 | |

| Maltreatment by parent | 0.20 | .27 | 0.74 | |

| History of sexual abuse | −0.03 | .24 | −0.13 | |

| Number of CM experiences | 0.25 | .11 | 2.38* | |

| Demographic risk | −0.05 | .10 | −0.52 | |

| Reduced Model | 1.54 (4, 95) | |||

| Positive parenting PTCb | ||||

| Intercept | 1.90 | .20 | 9.74*** | |

| Maltreatment by parent | −0.57 | .28 | −2.01* | |

| History of sexual abuse | −0.11 | .26 | −0.41 | |

| Number of CM experiences | 0.01 | .03 | 0.39 | |

| Demographic risk | −0.07 | .09 | −0.72 | |

| Number CM experiences X Demographic risk | 0.08 | .04 | 2.22* | |

| Full Model | R2 = .13 | 2.84 (5, 94)* | ||

Note:

Results are final models that include maltreatment by parent figure (0 = yes; 1 = no), lifetime experience of sexual abuse (experienced sexual abuse; 1 = no; 2 = yes), number CM experiences, and current demographic risk as covariates. If interaction terms were not significant, reduced models are presented excluding interactions.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Fig. 1.

Demographic risk moderates the relationship between number of maltreatment experiences and strength of positive parenting PTC. Regions of significance analyses.

Note: J-N analyses indicated that the relation between number of maltreatment experiences and strength of positive parenting PTC transitioned from non-significant to significant at the 89th percentile of the distribution of demographic risk, b = 0.12, SE = 0.06, t(94) = 1.98, p = .05. Estimates for strength of positive parenting PTC are derived using the sample mean for each of the covariates.

4. Discussion

Findings from the current study highlight the importance of examining positive and negative PTC in both general and domain specific views for understanding meanings made of CM experiences (Park, 2010; Simon et al., 2015). All mothers in this study changes in general views of themselves, others, and the world related to their CM experiences, with the vast majority reporting a mix of positive and negative changes. This finding is consistent with prior work showing that over half of youth with confirmed cases of sexual abuse report a mix of positive and negative PTC (Simon et al., 2015). A different picture emerged for parenting PTC, with the majority reporting only positive parenting changes (62% of the sample; 75% of those reporting parenting PTC). This proportion is higher than the 30% of mothers with sexual abuse histories who reported positive parenting changes in a study by Wright et al. (2007). The discrepant rates in positive parenting PTC could be due to methodological differences. Wright and colleagues invited women to share meanings made via written responses to an open-ended survey question. A sizeable number (22%) of mothers did not respond to the question, and 42% of those who did respond reported positive parenting changes. The higher frequency of positive parenting PTC in the current study may reflect greater ease or willingness to articulate PTC in the context of narrating experiences and their effects over time. Sample differences between this study of postpartum women and Wright’s study of mothers with children at varying ages may also contribute to the discrepant findings. Higher rates of positive PTC among postpartum women could suggest that perceptions of positive parenting PTC diminish as the challenges of parenting are more fully realized.

Maltreatment and individual characteristics were related to mothers’ parenting but not general PTC. Contrary to studies reporting that sexual abuse uniquely predicts poor adjustment (e.g., Finkelhor et al., 2007), we did not find significant relations between a history of sexual abuse and perceptions of PTC. Instead, the number not type of CM experiences was related to stronger negative parenting PTC, and demographic risk did not moderate this association.

When predicting positive parenting changes, indicators of more severe CM (i.e., perpetration by parent figure, more CM experiences) and demographic risk were associated with stronger changes. Moreover, demographic risk moderated the association between the number of CM experiences and positive parenting PTC. Among those with roughly two or more demographic risk factors, more maltreatment experiences predicted stronger positive parenting changes. Although this represented only 11% of the current sample of mothers, the relative level of demographic risk for the transition point is relatively low given that the potential range of scores was 0 to 5. Further work is clearly warranted with samples demonstrating more diversity in demographic risk than the current sample. Nonetheless, the moderated effect points to the salience of contextual factors for the ways postpartum women view the effects of their CM on parenting. Although some might consider mothers with extensive maltreatment histories and current demographic risk to be at greatest risk for poor adaptation, women themselves may view motherhood as a hopeful turning point to be a different kind of parent to their own children (Sawyer and Ayers, 2009; Wright et al., 2012). As one of our participating mothers stated, she wanted to “be a good parent” and did not want her child “to see me act the way my mother did toward me. And I don’t wanna treat him like that. . . Um, just try not to follow in my mother’s footsteps basically.” Another mother stated, “I don’t stand for abuse anymore. . .Yes, just how to be more patient and don’t use physical violence, you know as your method of um punishment.”

The distinct findings for general and parenting PTC may also speak to assimilation and accommodation processes in meaning making during the postpartum period. Whereas assimilation involves situational appraisals that are consistent with existing global meanings, accommodation entails changing global beliefs in light of new experiences or meanings (Park, 2010). When viewed from this lens, the associations between negative general and parenting PTC might reflect assimilation processes in the construction of parenting meanings that are consistent with general views. However, the lack of association between positive general and parenting PTC along with the different patterns of regression results for positive parenting PTC suggest a relative absence of assimilation or accommodation. Instead, many postpartum mothers appear to derive positive parenting (situational) meanings about their CM experiences in ways that may be shaped more by characteristics of their maltreatment experiences and concurrent demographic context than by general PTC or core views. Longitudinal developmentally-informed studies are needed to determine whether and under what conditions positive meanings about parenting may prompt accommodations in general views or whether and when assimilation of parenting meanings occur as a function of general core views.

The goals of this study were to document the presence of general and parenting PTC, and examine their relations with maltreatment and demographic characteristics. Additional work is needed to examine connections between PTC and women’s mental health, parenting behavior and child outcomes. If embedded in a prospective developmental framework, such work could improve our understanding of what motherhood means to women with histories of CM, how they integrate this new role into the rest of their lives and identity, and relations with parenting practices. The dynamics of motherhood are intricately entwined with memories of childhood along with the unfolding development of the child. According to Wright and colleagues (2012), women report having to mother “through the pain” (p. 542) of their own childhood experiences which were re-opened and re-lived through motherhood. As children age, new developmental milestones, such as autonomy granting and healthy separation, may be difficult for mothers with histories of CM (Wright et al., 2012).

4.1. Clinical implications

For service providers, our findings underscore the rich and varied meanings women with CM histories bring to bear on their emerging roles as mothers. During the transition to motherhood, women actively construct new meanings about the implications of past CM experiences for themselves as parents, and these meanings may be distinct from more general views of the self, relationships, or world. For example, women may exhibit positive perceptions of themselves and abilities related to being a parent that may differ from how they view themselves more generally. Similarly, other researchers have reported that while some mothers with CM histories function well overall, others struggle within certain areas (Wright, Fopma-Loy, & Fisher, 2005).

The current findings are also relevant to psychotherapeutic efforts to promote adaptive meaning making, a key component of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Cohen et al., 2006), Cognitive Processing Therapy (Resick & Schnicke, 1992), and Narrative Exposure Therapy (Schauer, Neuner, & Elbert, 2011). Each of these evidence-based trauma-focused treatments facilitate trauma processing through the creation of coherent accounts of traumatic experiences that allow for a developmentally adaptive understandings. Our findings suggest that attempts to mitigate negative meanings made about parenting may be especially important for women with a history of multiple maltreatment experiences. Additionally, postpartum women may be especially receptive to constructing CM narratives infused with realistic positive meanings about parenting, given their expressed desire to become good parents. This may be especially true for women who were maltreated by parent figures or who experienced multiple maltreatment experiences and are exposed to contextual risk factors. Given the lack of relation between positive and negative parenting changes, efforts to build upon positive meanings should accompany rather than take the place of encouraging acceptance or re-appraisal of negative PTC.

Efforts to mitigate negative meanings and build realistic positive views might also be a useful component of parenting programs. While our findings cannot speak to parenting behavior, the many reports of positive parenting changes shared by the women in this study suggest postpartum mothers may be particularly motivated for the hard work of therapy or parenting interventions. Paradoxically, the high number of exclusively positive parenting changes might also signal low perceived need for intervention during the early postpartum period. Given evidence linking maternal CM to less competent parenting, bridging the gap between perceived need and the potential value of early intervention may be critical for engaging women with CM histories (e.g., Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2003). Rather than appeal to women’s potential vulnerability, programs that tap into perceptions of positive change to support well-being and promote competence in ways that are guided by the unique needs, characteristics, and meanings made of mothers with this kind of past may be particularly effective (Muzik et al., 2015; Park, 2010). Over time, realistic and positive parenting views might become catalysts for accommodations in negative global views with the potential to benefit broader psychosocial adaptation (Fischer & Pruyne, 2003; Park, 2010; Simon et al., 2015; Simon, Feiring, & Cleland, 2016).

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants to Maria Muzik from the National Institutes of Health (RR017607; MH080147) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (UL1TR000433) as well as grants to Valerie Simon from the National Institutes of Health (HD61230 and MH074997).

References

- Banyard VL. The impact of childhood sexual abuse and family functioning on four dimensions of women’s later parenting. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(11):1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8(4):334–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LJ, Slade A. The Psychology and Psychopathology of Pregnancy. In: Zeanah CH, editor. The Handbook of Infant Mental Health. 2. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Woolger C, Power TG, Smith KD. Parenting difficulties among adult survivors of father-daughter incest. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(2):239–249. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90031-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AW, Laursen B. Changing relationships, changing youth interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(1):55–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431603260882. [Google Scholar]

- Easton SD, Coohey C, Rhodes AM, Moorthy MV. Posttraumatic growth among men with histories of child sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2013;18(4):211–220. doi: 10.1177/1077559513503037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer KW, Pruyne E. Reflective thinking in adulthood: Emergence, development, and variation. In: Demick J, Andreoletti C, editors. Handbook of adult development. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(1):149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MR, Mishler EG, Koenen K, Harney PA. In the aftermath of sexual abuse: Making and remaking meaning in narratives of trauma and recovery. Narrative Inquiry. 2000;10:291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York, NY: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Victims of violence. In: Everly G, Lating J, editors. Psychotraumatology: Key papers and core concepts in post-traumatic stress. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Linley P. Positive adjustment to threatening events: An organismic valuing theory of growth through adversity. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:262–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Cassidy J, Lyons-Ruth K, Zir Y. Attachment, stress and psychopathology: A developmental pathways model. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. Cambridge: University Press; 2006. pp. 333–369. [Google Scholar]

- Lin TH. A comparison of multiple imputation with EM algorithm and MCMC method for quality of life missing data. Quality & Quantity. 2010;44(2):277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman EL, McMillan HL, Boyle MH. Childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders among single and married mothers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:73–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, McClean KC. Narrative Identity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(3):233–238. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen C, Zuravin S, Rideout G. Perceived benefit from child sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:1037–1043. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Lewis J, Ethier K, Kershaw T, Ickovics J. Relationship violence among adolescent mothers: Frequency, dyadic nature, and implications for mental health. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;12:302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mu SK, Zhou W. Handling missing data: Expectation maximization algorithm and Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm. Advances in Psychological Science. 2011;19:1083–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Muzik M, Rosenblum KL, Alfafara EA, Schuster MM, Miller NM, Waddell RM, Kohler ES. Mom Power: Preliminary outcomes of a group intervention to improve mental health and parenting among high-risk mothers. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2015;18(3):507–521. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Locke TF. Intergenerational cycle of maltreatment: A popular concept obscured by methodological limitations. Child Abuse & Neglect: An International Journal. 2001;25:1219–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136 doi: 10.1037/a0018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riessman CK. Narrative Analysis (Qualitative Research Methods) 1. Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64(1):80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Ayers S. Post-traumatic growth in women after childbirth. Psychol Health. 2009;24(4):457–471. doi: 10.1080/08870440701864520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440701864520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy: A short term treatment for traumatic stress disorders. 2. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seltmann LA, Wright M. Perceived parenting competencies following childhood sexual abuse: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 2013;28:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Kane Low LM, Sperlich MI, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Prevalence, trauma history and risk for PTSD among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;114(4):839–847. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Sperlich M, Kane Low L, Ronis DL, Muzik M, Liberzon I. Child abuse history, posttraumatic stress disorder, postpartum mental health, and bonding: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2013;58:57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch J, de Dassel T. Exploring posttraumatic outcomes as a function of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2009;18:623–640. doi: 10.1080/10538710903317224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon VA, Feiring C, McElroy S. Making meaning of traumatic events: Youths’ strategies for processing childhood sexual abuse are associated with psychosocial adjustment. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:229–241. doi: 10.1177/1077559510370365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559510370365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon VA, Feiring C, Cleland CM. Early stigmatization, PTSD, and perceived negative reactions of others predict subsequent strategies for processing child sexual abuse. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6(1):112–123. doi: 10.1037/a0038264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon VA, Smith E, Fava N, Feiring C. Positive and negative posttraumatic change following childhood sexual abuse are associated with youths’ adjustment. Child Maltreatment. 2015;20:278–290. doi: 10.1177/1077559515590872. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559515590872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JA. Narrative identity and meaning making across the adult lifespan: An introduction. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:437–460. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DN. The Motherhood Constellation: A Unified View of Parent-infant Psychotherapy. Karnac Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(5):748–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M, Fopma-Loy J, Fisher S. Multidimensional assessment of resilience in mothers who are child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1173–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M, Crawford E, Sebastian K. Positive resolution of childhood sexual abuse experiences: The role of coping, benefit-finding and meaning-making. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Wright MO, Fopma-Loy J, Oberle K. In their own words: The experience of mothering as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. Development & Psychopathology. 2012;24:537–552. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]