Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association between household air pollution (HAP) with lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in children younger than 5 years old and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study took place in two cities in Patagonia. Using systemic random sampling, we selected households in which at least one child <5 years had lived and/or a child had been born alive or stillborn. Trained interviewers administered the questionnaire.

Results

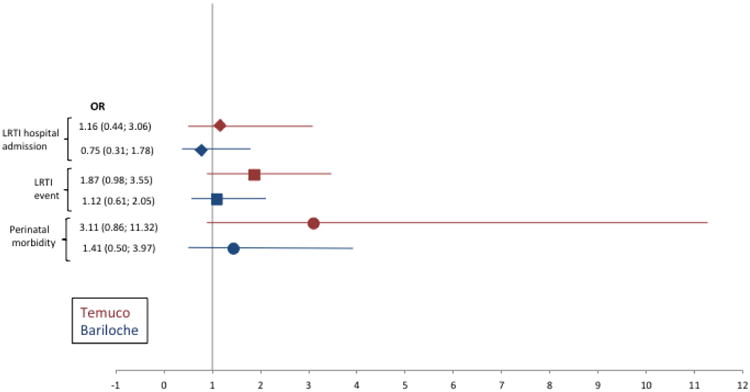

We included 926 households with 695 pregnancies and 1,074 children. Household cooking was conducted indoors in ventilated rooms and the use of wood as the principal fuel for cooking was lower in Temuco (13% vs 17%). In exposed to biomass fuel use, the adjusted OR for LRTI was 1.87 (95% CI 0.98-3.55; p = 0.056) in Temuco and 1.12 (95% CI 0.61-2.05; p = 0.716) in Bariloche. For perinatal morbidity, the OR was 3.11 (95% CI 0.86-11.32; p = 0.084) and 1.41 (95% CI 0.50-3.97; p = 0.518), respectively. However, none of the effects were statistically significant (p >0.05)

Conclusion

The use of biomass fuel to cook in traditional cookstoves in ventilated dwellings may increase the risk of perinatal morbidity and LRTI.

Keywords: Lower respiratory tract illness, household air pollution, adverse pregnancy outcomes, children, Latin America

Introduction

Globally, about 3 billion people depend on solid fuels for cooking (400 million people use coal and 2.6 billion use traditional biomass). Among this population, three percent live in Latin American countries (LAC). Households in developing countries commonly use wood as their primary cooking fuel, followed by charcoal and gas. Moreover, only five percent of the people who use biomass fuels for cooking have access to clean cookstoves (Legros et. al., 2009).

The use of biomass fuels in poorly ventilated dwellings results in high levels of household air pollution (HAP). In fact, HAP contributed to approximately 3.5 million deaths in 2010 and accounts for 4.5% of the global burden of disease (Lim et. al., 2012, Smith et. al., 2014).

There are different models of traditional cookstoves, ranging from three-stone open fires to closed models, and are made of various materials (i.e. bricks, metal, concrete). Stoves can include a chimney or a hood. Closed traditional stoves with chimneys enclose the fire and exhaust particulate matter and combustion byproducts, minimizing HAP (World Bank, 2011, Legros et. al., 2009).

Lower tract respiratory infection (LRTI) is a common cause of illnesses in children younger than five years of age and are the leading cause of global childhood mortality (Benguigui et. al., 1999, Nair et. al., 2010, Wardlaw et. al., 2006). In fact, in LAC, 12% of under-five deaths are caused by pneumonia (World Health Organization, 2010). Annually, 15 million preterm births occur worldwide and 32 million infants are born small for gestational age in low-income and middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2011, Blencowe et. al., 2012, Lee et. al., 2013). These two neonatal conditions are well known causes of increased morbidity, mortality and lifetime disability.

HAP has been linked to an increased risk of LRTIs and adverse perinatal outcomes (Bruce et. al., 2000, Burki, 2011). Systematic reviews have reported 1.8, 1.4, and 1.5 fold increases in the odds of LRTIs, low birth weight (LBW), and stillbirths respectively, all of which are associated with HAP (Pope et. al., 2010, Dherani et. al., 2008). Since 1995, the reduction of HAP related to the use of solid fuels for cooking has been identified as a potential intervention for preventing pneumonia in children (Kirkwood et. al., 1995). In Latin America, a few studies have examined the association between HAP and LRTI or adverse perinatal outcomes. Those studies were conducted in Brazil (Fonseca et. al., 1996, Victora et. al., 1994), Guatemala (Smith et. al., 2010, Smith et. al., 2011, Smith et. al., 2000, Boy et. al., 2002) and Peru (Yucra et. al., 2011). Argentina contributed to a nine-country survey regarding biomass use among pregnant women; however, this study did not explore its association with health outcomes (Kadir et. al., 2010). To our knowledge, studies exploring the impact of HAP and child or maternal health have not been conducted in Argentina or Chile or in any other upper-middle income countries with similar use of biomass fuel or sociodemographic characteristics.

Preliminary data from the PRISA study (Rubinstein et. al., 2011), which is an ongoing population-based cohort study conducted within four cities in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, showed a higher than average exposure to HAP in Bariloche (Argentina) and Temuco (Chile) with 21% and 26% of households exposed, respectively. Figure S1 (supplementary data) shows the conceptual framework and the proposed relation between exposure, outcomes and other relevant variables.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate whether exposure to HAP in Bariloche and Temuco is related to LRTI in children less than 5 years old and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study aimed to explore the effect of HAP due to solid fuels in pregnant women and children under five years of age. Our primary objective was to estimate the effect of HAP on the incidence, hospital admissions, and deaths caused by LRTI (pneumonia and bronchiolitis) in children <5 years. Our secondary aim was to evaluate whether adverse pregnancy outcomes were associated with exposure to HAP.

Population and Sampling

The study was conducted in two cities, Bariloche (Argentina) and Temuco (Chile), with 134,000 and 245,000 residents, respectively, according to the most recent census data (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, 2010, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2002). Both cities are located in cold areas of the Argentine or Chilean Patagonia.

In the 2-stage sampling strategy, census radii were first selected according to the percentage of the population with high risk of HAP from cooking with biomass fuels in poorly vented dwellings, based on data from the PRISA study (Rubinstein et. al., 2011). Next, households within the chosen census radii were selected by systematic random sampling from a randomly selected starting point using a sampling interval proportional to the size of each census radius.

Households were eligible to participate in the study if at least one child under the age of five had resided in the home in the past five years and/or a child had been born alive or stillborn in the household in the last 3 years. Households were then included in the study if a key informant was able and willing to give written consent.

Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

Data were collected between January 2013 and February 2014 using a questionnaire designed for face-to-face verbal administration. During the household visit, a trained interviewer administered the questionnaire to the mother or, if this was not possible, to a key informant. We collected information related to LRTI, children's perinatal and health history, adverse pregnancy outcomes, history of pregnancies reaching more than six months gestational age, exposure to biomass fuels for cooking and heating in the last five years, and socio-demographic characteristics. The interviewer registered all types of cookstoves (clean; traditional cookstoves with or without chimney) by direct observation. Birth weight and total number of pneumococcal vaccine doses were assessed from personal health records. Data related to deaths or hospitalizations due to respiratory causes were ascertained by examining medical records retrieved from the local health facilities.

Exposure

A standardized questionnaire was used to collect information related to the type of fuel used for cooking (wood, coal, gas, electricity, or other, such as crop waste), and the amount of time (per day, days per week, and total years) of use of each type of fuel. The number of hours of use for each type of fuel per year was then calculated. HAP exposure was subsequently defined as the use of wood or coal as the primary fuel used for cooking when the hours/year of use of wood or coal was higher than the hours/year for that of gas or electricity. We also explored the use of biomass fuel for cooking for more than 200 hours/year as the exposure variable (Perez-Padilla et. al., 1996).

Other variables related to HAP exposure were analyzed including: cookstove type; presence of ventilation (a window that can be opened in the kitchen); children or pregnant women sleeping in the same room used for cooking; and time spent by children in the kitchen while cooking was being done with biomass. Cookstove type was categorized as: clean cookstove (gas or electric); closed traditional cookstove with or without chimney, or open fire.

Outcomes

We collected information related to episodes of bronchiolitis and pneumonia diagnosed by a physician in the previous year. In addition, we asked about the number of treatments with β2 agonist medications or antibiotics. Treatment was used as a cross-reference to verify the episode of bronchiolitis or pneumonia. We also gathered information about children's lifetime history of hospitalizations due to pneumonia or bronchiolitis. LRTI was defined as at least one episode of bronchiolitis or pneumonia in the last year. An LRTI-related hospitalization was defined as at least one event during the child's lifetime. Perinatal morbidity was a composite outcome that included LBW (birth weight less than 2500 g) or pre-term birth (less than 37 weeks of gestation).

Potential Confounders

Critical overcrowding was defined as when the number of inhabitants divided by the number of rooms (excluding bathroom/s and kitchen) was higher than three. Educational attainment of the mother or the primary caregiver of the child was analyzed as a categorical variable (primary, secondary, or tertiary education). Environmental tobacco exposure (ETS) was considered present if someone had smoked inside the house at least one day in the week prior to the survey.

The use of biomass for heating purposes was analyzed as a dichotomous variable and included in the models as a potential confounder.

Women who smoked at all during pregnancy were considered as “smokers during pregnancy”, whereas women who quit smoking when they found out about their pregnancy were considered as “non-smokers during pregnancy” for the analysis. Women also reported comorbidities pre-existing or during pregnancy (i.e. high blood sugar or high blood pressure).

According to national vaccination programs (the same in both countries), pneumococcal vaccine schedule was considered complete for child's age for three doses received in children over one year of age, two doses in children between 4 and 12 months, and one dose in children between 2 and 4 months. Complete vaccination for age was assessed by key informant report. Asthma in children <5 years is difficult to diagnose and can be categorized in different ways (i.e. wheezing children). For this reason, we also asked about the use of preventive treatment with inhaled corticosteroids and/or long acting β2 agonists, which was included as a confounder in our analysis. Children's overall health status was assessed by means of proxy, using the SF-36 question.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated a sample size of 450 households per site, based on a statistically significant alpha level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 80% while assuming a LRTI incidence between 50/1,000 and 60/1,000 (Nair et. al., 2010), and an increased risk of LRTI in exposed children (OR) between 1.45 and 2.10 (Dherani et. al., 2008).

We described the frequency and distribution of population variables in each location. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) models to examine the association between household exposure to biomass fuels (HAP) and development of LRTI, LRTI mortality, and adverse pregnancy outcomes, while accounting for potential correlation within households. Relevant variables considered to be potential confounders were added to the models. Additionally, we tested first-order interaction terms involving the exposure variable and other covariates of interest (educational attainment, overcrowding, and location). Because of the presence of a statistically significant interaction between location (Bariloche or Temuco) and exposure in LRTI models, they were analyzed separately. The statistical significance of these terms was evaluated using the log likelihood test at a 0.05 significance level. We assessed the overall goodness-of-fit of the final model through the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2000) and performed model diagnostics, including deviance residuals and delta-beta statistics. Separate analyses were performed using children and pregnancies as the unit of analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software version 11.0. (StataCorp., 2009).

Results

Population Characteristics

The study included 926 households (450 in Bariloche and 476 in Temuco), with information on 695 pregnancies (356 in Bariloche and 339 in Temuco) and 1,074 children (537 in each site); data on pregnancy outcomes were missing for one pregnancy. Information was obtained from a household key informant, though the mother always gave information specific to pregnancy. The primary caregiver was the person who was primarily responsible for the care of the child, whether they were a family member or not,. The refusal rate was lower than 10%.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of households, pregnancies, and children. Compared to Temuco, households in Bariloche were of lower socioeconomic status, had primary caregivers who were less educated, were more overcrowded (26.7% vs 1.7%), and had children with a higher exposure to ETS (31.3% vs 9.1%).

Table 1. Main Characteristics of Households, pregnancies and children in Bariloche (Argentina) and Temuco (Chile).

| Number of households (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample n=926 | Bariloche n=450 | Temuco n=476 | |

| Household Characteristics | |||

| Critical Overcrowding* | 128 (13.8) | 120 (26.7) | 8 (1.7) |

| TB exposure | 34 (3.7) | 17 (3.8) | 17 (3.6) |

| ETS# exposure | 184 (19.9) | 141 (31.3) | 43 (9.1) |

| Educational attainment of the primary caregiver/mother: | |||

| Primary education | 238 (25.8) | 185 (41.2) | 53 (11.2) |

| Secondary education | 466 (50.4) | 242 (53.9) | 224 (47.2) |

| Tertiary education | 220 (23.8) | 22 (4.9) | 198 (41.7) |

| Number of pregnancies (%) | |||

| Overall sample n=695 | Bariloche n=356 | Temuco n=339 | |

| Maternal and Pregnancy Characteristics | |||

| Maternal age | |||

| ≤19 | 141 (20.5) | 79 (22.3) | 62 (18.6) |

| 20-34 | 478 (69.5) | 250 (70.4) | 228 (68.5) |

| >35 | 69 (10.0) | 26 (7.3) | 43 (12.9) |

| Self-report of high blood sugar or diabetes | 50 (7.2) | 10 (2.8) | 40 (11.9) |

| Self-report of high blood pressure or hypertension | 76 (11) | 43 (12.1) | 33 (9.8) |

| Self-report of other chronic conditions (pre-existence)¥ | 73 (10.5) | 30 (8.4) | 43 (12.7) |

| 4 or more antenatal care visits | 650 (94.1) | 337 (95.7) | 313 (92.3) |

| Self-report of high blood sugar or diabetes during pregnancy | 51 (7.3) | 19 (5.3) | 32 (9.4) |

| Self-report of hypertension during pregnancy | 66 (9.6) | 46 (13) | 20 (6) |

| Self-report of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | 12 (1.9) | 5 (1.6) | 7 (2.2) |

| Smoke during pregnancy | 122 (17.6) | 76 (21.4) | 46 (13.6) |

| Cesarean delivery | 255 (36.9) | 107 (30.1) | 148 (44.1) |

| Birth weight, grams, (SD) | 3.320 (0.520) | 3.253 (0.557) | 3.393 (0.466) |

| Number of children (%) | |||

| Overallsample n=1074 | Bariloche n=537 | Temuco n=537 | |

| Children Characteristics | |||

| Girls, n, (SD) | 529 (49.3) | 263 (49) | 266 (49.5) |

| Mean Age, years (SD) | 2.52 (1.47) | 2.53 (1.42) | 2.51 (1.52) |

| Birth weight, grams (SD) | 3.314 (0.537) | 3.246 (0.542) | 3.386 (0.523) |

| Preterm birth | 82 (7.7) | 47 (8.8) | 35 (6.5) |

| Low birth weight | 59 (5.6) | 42 (7.8) | 17 (3.3) |

| Never breastfed | 61 (5.7) | 23 (4.2) | 38 (7.1) |

| Complete immunization (referred) | 986 (96.3) | 484 (97.2) | 502 (95.4) |

| Any dose of pneumococcal vaccine (by observation of records) | 420 (39.1) | 317 (59.0) | 103 (19.2) |

| Regular or bad health reported by proxy | 168 (15.7) | 63 (11.8) | 105 (19.6) |

| Illnesses (referred) | |||

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Heart condition | 15 (1.4) | 9 (1.7) | 6 (1.1) |

| Asthma | 85 (7.9) | 22 (4.1) | 63 (11.7) |

| Preventive asthma treatment | 160 (15.2) | 75 (14.9) | 85 (16.1) |

Number of inhabitants/number of rooms (excluding bathroom and kitchen)>3

Environmental tobacco smoke

Anemia, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Asthma, Depression/Psychiatric Illness, Epilepsy, Scleroderma, Gastritis/Ulcer, Hypothyroidism/Hyperthyroidism, Insulin resistance, Lupus, Purple, Antiphospholipid syndrome and other hematologic disorders, Sinusitis, Cancer

The characteristics of the women and their pregnancies were different between the two locations. Bariloche had a slightly higher rate of adolescent pregnancies (22.3% vs 18.6%), more women who smoked during pregnancy (21.4% vs 13.6%), less cesarean delivery (30.1% vs 44.1%), and a lower mean birth weight by 140 grams. Women in Temuco reported higher rates of high blood sugar or diabetes (11.9% vs 2.8%) and lower rates of hypertension during pregnancy (6% vs 13%). In both places, more than 90% of pregnancies had four or more prenatal care visits.

The characteristics of children were similar between the two locations, with the exception of lower rates of LBW (3.3% vs 7.8%) and preterm birth (6.5% vs 8.8%) in Temuco, and a higher proportion of breastfed children in Bariloche. In both sites, 15% of children were receiving preventive asthma treatment and more than 95% had their immunization schedule complete. No child included in the study had a history of tuberculosis.

The different types of cooking fuels and cookstoves used are described in Table 2. In both cities, closed traditional cookstoves were used for cooking with biomass fuels (see Figure S2 in the supplementary data). In Temuco, 15.8% of traditional cookstoves did not have chimneys and the use of wood or charcoal as the primary fuel source for cooking was slightly lower than in Bariloche (13% vs 17%). The percentage of households using biomass for more than 200 hours/year was similar in both study sites (27.6% in Bariloche and 26.3% in Temuco). Also in both cities, more than 93% of households used gas or electricity for cooking and most households reported cooking indoors in ventilated rooms. Irrespective of the fuel used for cooking, most households in both sites used wood or coal to heat their homes.

Table 2. Characteristics of Exposure to biomass fuels at Households, pregnancies and children.

| Number of households (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample n=926 | Bariloche n=450 | Temuco n=476 | |

| Exposure at household level | |||

| Use of wood or charcoal as principal cooking fuel | 138 (14.9) | 76 (16.9) | 62 (13) |

| Type of cookstove°: | |||

| -Clean (only)∞ | 675 (73) | 333 (74.2) | 342 (71.9) |

| -Traditional cookstove with ventilation | 174 (18.8) | 115 (25.6) | 59 (12.4) |

| -Traditional cookstove without ventilation | 76 (8.2) | 1 (0.2) | 75 (15.8) |

| Kitchen without window that can be opened | 196 (21.6) | 152 (34.0) | 44 (9.6) |

| Exclusive use of wood or charcoal for cooking | 29 (4.1) | 17 (4.9) | 12 (3.4) |

| Cooking fuel used (more than one fuel per household) | |||

| -Gas or electricity | 900 (97.4) | 436 (97.3) | 464 (97.5) |

| -Wood or charcoal | 312 (34.1) | 164 (37.3) | 148 (31.1) |

| -Kerosene | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.6) |

| -Other | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Heating fuel used (more than one fuel per household) | |||

| -Gas or electricity | 448 (49) | 307 (69.9) | 141 (29.6) |

| -Wood or charcoal | 661 (72.3) | 241 (55) | 420 (88.2) |

| -Kerosene | 59 (6.7) | 0 | 59 (12.4) |

| -Other | 1 (0,1) | 0 | 1 (0,2) |

| Number of pregnancies (%) | |||

| Whole sample n=695 | Bariloche n=356 | Temuco n=339 | |

| Exposure at individual level (pregnancies) | |||

| Use of wood or charcoal as principal cooking fuel | 107 (15.4) | 63 (17.7) | 44 (13) |

| Exposure to biomass while sleeping during pregnancy | 37 (5.4) | 36 (10.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of children (%) | |||

| Whole sample n=1074 | Bariloche n=537 | Temuco n=537 | |

| Exposure at individual level (children) | |||

| Use of wood or charcoal as principal cooking fuel | 166 (15.5) | 93 (17.3) | 73 (13.6) |

| Average of biomass exposure during the day, hours (SD) | 2.33 (2.94) | 2.15 (1.65) | 2.73 (4.76) |

| Exposure to biomass while sleeping | 117 (10.9) | 110 (20.6) | 7 (1.3) |

Direct observation, more than one cookstove per household

The only coookstove in the house is clean (gas or electricity)

LRTI and Exposure to HAP

The association between LRTI and exposure to HAP as well as to other factors, by location, is shown in Table 3. In Bariloche, 29.1% of children had at least one event of LRTI in the previous year. The unadjusted OR for LRTI in those exposed to HAP was 1.35 (95% CI 0.84-2.18; p = 0.215). After adjusting for the use of wood or charcoal as a heating fuel, kitchen without ventilation (a window that can be opened), overcrowding, educational attainment of the primary caregiver, TB exposure, ETS, prematurity, LBW, breastfeeding, age, any dose of pneumococcal vaccine, health status as reported by proxy, and asthma preventive treatment, the adjusted OR for LRTI remained non-significant at 1.12 (95% CI 0.61-2.05; p=0.716).

Table 3.

Exposure to IAP and other factors, and its association with LRTI events (bivariate analysis).

| Bariloche | Temuco | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | LRTI (%) | OR (95%CI) | p | n (%) | LRTI (%) | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| All infants | 537 (100) | 156 (29.1) | - | - | 537 (100) | 315 (58.7) | - | - |

| Exposure to IAP | ||||||||

| Use of wood or charcoal as principal cooking fuel | ||||||||

| Yes | 93 (17.3) | 32 (34.4) | 1.35 (0.84-2.18) | 0.215 | 73 (13.6) | 49 (67.1) | 1.50 (0.88-2.56) | 0.136 |

| No | 444 (82.7) | 124 (27.9) | - | - | 464 (86.4) | 266 (57.3) | - | - |

| Traditional cookstove without ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (0.2) | 1 (100) | 1 | - | 86 (16.0) | 53 (61.6) | 1.16 (0.72-1.89) | 0.537 |

| No | 535 (99.8) | 155 (29.0) | - | - | 451 (84.0) | 262 (58.1) | - | - |

| Kitchen without ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 193 (36.2)) | 76 (39.4) | 2.13 (1.45-3.14) | 0.000 | 48 (9.3) | 26 (54.2) | 0.81 (0.44-1.48) | 0.496 |

| No | 340 (63.8 | 80 (23.5) | - | - | 471 (90.8) | 277 (58.8) | - | - |

| Wood or charcoal as a heating fuel | ||||||||

| Yes | 294 (56.1) | 96 (32.7) | 1.51 (1.03-2.25) | 0.036 | 477 (88.8) | 275 (57.7) | 0.68 (0.39-1.21) | 0.193 |

| No | 230 (43.9) | 56 (24.4) | - | - | 60 (11.2) | 40 (66.7) | - | - |

| Average hours of biomass exposure during the day (SD) | 2.15 (1.65) | 2.58 (1.90) | 1.24 (0.98-1.58) | 0.076 | 2.73 74.76) | 3.26 (5.66) | 1.41 (0.70-2.83) | 0.335 |

| Exposure to biomass while sleeping | ||||||||

| Yes | 110 (20.6) | 32 (29.1) | 1.00 (0.63-1.60) | 0.984 | 7 32/(1.3) | 5 (71.4) | 1.75 (0.34-9.11) | 0.506 |

| No | 424 (79.4) | 123 (29.0) | - | - | 529 (98.7) | 310 (58.6) | - | - |

| Critical Overcrowding * | ||||||||

| Yes | 159 (29.6) | 49 (30.8) | 1.13 (0.75-1.70) | 0.554 | 13 (2.42) | 7 (53.9) | 0.78 (0.24-2.54) | 0.683 |

| No | 378 (70.4) | 107 (28.3) | - | - | 524 (97.6) | 308 (58.8) | - | - |

| TB exposure | ||||||||

| Yes | 23 (4.3) | 10 (43.5) | 1.97 (0.84-4.63) | 0.120 | 17 (3.2) | 8 (47.1) | 0.61 (0.23-1.61) | 0.319 |

| No | 514 (95.7) | 146 (28.4) | - | - | 520 (96.8) | 307 (59.0) | - | - |

| ETS# exposure | ||||||||

| Yes | 169 (31.5) | 58 (34.3) | 1.44 (0.97-2.13) | 0.069 | 49 (9.2) | 28 (57.1) | 0.92 (0.50-1.69) | 0.791 |

| No | 368 (68.5) | 98 (26.6) | - | - | 486 (90.8) | 286 (58.9) | - | - |

| Educational attainment of the primary caregiver: | ||||||||

| Primary education | 223 (41.6) | 62 (27.8) | 1.30 (0.50-3.42) | 0.594 | 59 (11.0) | 35 (59.3) | 0.98 (0.54-1.77) | 0.938 |

| Secondary education | 287 (53.5) | 88 (30.7) | 1.49 (0.58-3..88) | 0.410 | 258 (48.1) | 149 (57.8) | 0.90 (0.62-1.31) | 0.595 |

| Tertiary education | 26 (4.9) | 6 (23.1) | ref | - | 219 (40.9) | 131 (59.8) | ref | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 2.53 (1.42) | 2.49 (1.29) | 0.97 (0.85-1.10) | 0.627 | 2.51 (1.52) | 2.82 (1.36) | 1.38 (1.23-1.56) | 0.000 |

| Preterm birth | ||||||||

| Yes | 47 (8.8) | 13 (27.7) | 0.93 (0.48-1.81) | 0.829 | 35 (6.5) | 21 (60.0) | 1.14 (0.56-2.33) | 0.715 |

| No | 490 (91.3) | 143 (29.2) | - | - | 501 (93.5) | 294 (58.7) | - | - |

| Low birth weight | ||||||||

| Yes | 42 (7.8) | 15 (35.7) | 1.40 (0.72-2.70) | 0.324 | 17 (3.3) | 7 (41.2) | 0.48 (0.17-1.30) | 0.150 |

| No | 495 (92.2) | 141 (28.5) | - | - | 492 (96.7) | 293 (59.5) | - | |

| Never breastfed | 23 (4.3) | 6 (26.1) | 0.86 (0.33-2.23) | 0.761 | 38 (7.1) | 24 (63.2) | 1.20 (0.61-2.37) | 0.595 |

| Ever breastfed | 513 (95.7) | 149 (29.0) | - | - | 496 (92.9) | 289 (58.3) | - | - |

| Any dose of pneumococcal vaccine (records) | 317 (59.0) | 95 (30.0) | 1.12 (0.76-1.64) | 0.564 | 103 (19.2) | 62 (60.2) | 1.08 (0.69-1.67) | 0.738 |

| No pneumococcal vaccine | 220 (41.0) | 61 (27.7) | - | - | 434 (80.8) | 253 (58.3) | - | - |

| Regular or bad health reported by proxy | 63 (11.8) | 42 (66.7) | 6.31 (3.58-11.11) | 0.000 | 105 (19.6) | 93 (88.6) | 8.22 (4.23-15.99) | 0.000 |

| Good, very good or excellent health by proxy | 469 (88.2) | 113 (24.1) | - | - | 431 (80.4) | 222 (51.5) | - | - |

| Reference of asthma | ||||||||

| Yes | 22 (4.1) | 19 (86.4) | 17.45 (5.08-59.87) | 0.000 | 63 (11.7) | 60 (95.2) | 19.31 (5.57-66.99) | 0.000 |

| No | 514 (95.9) | 137 (26.7) | - | - | 474 (88.3) | 255 (53.8) | ||

| Preventive asthma treatment | ||||||||

| Yes | 75 (14.3) | 62 (82.7) | 18.54 (9.82-35.00) | 0.000 | 85 (16.1) | 76 (89.4) | 7.72 (3.74-15.92) | 0.000 |

| No | 451 (85.7) | 93 (20.6) | - | - | 444 (83.9) | 234 (52.7) | - | - |

Number of inhabitants/number of rooms (excluding bathroom and kitchen)>3

Environmental tobacco smoke

Statistically significant results are shown in italic

In Temuco, 58.7% of children had at least one LRTI event. The unadjusted OR for LRTI in those exposed to HAP was 1.50 (95% CI 0.88-2.56; p = 0.136). The adjusted OR of LRTI in exposed children (adjusted for the use of wood or charcoal as a heating fuel, overcrowding, educational attainment of the primary caregiver, TB exposure, ETS, prematurity, LBW, breastfeeding, age, any dose of pneumococcal vaccine, health status as reported by proxy, and asthma preventive treatment) was 1.87 (95% CI 0.98-3.55; p = 0.056).

Table 4 shows the association between hospital admissions due to LRTI with HAP and other factors. In Bariloche, 11.2% of children were hospitalized at any point during their lifetime due to a LRTI. The unadjusted and adjusted ORs for hospital admissions in exposed children were 1.01 (95% CI 0.49-2.10; p = 0.977) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.31-1.78; p = 0.514), respectively.

Table 4.

Exposure to IAP and other factors, and its association with LRTI hospital admissions (bivariate analysis).

| Bariloche | Temuco | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | LRTI Admissions (%) | OR (95%CI) | p | n (%) | LRTI Admissions (%) | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| All | 537 (100) | 60 (11.2) | 537 (100) | 33 (6.2) | ||||

| Exposure to IAP | ||||||||

| Use of wood or charcoal as principal cooking fuel | ||||||||

| Yes | 93 (17.3) | 10 (10.8) | 1.01 (0.49-2.10) | 0.977 | 73 (13.6) | 7 (9.6) | 1.74 (0.73-4.14) | 0.210 |

| No | 444 (82.7) | 50 (11.3) | - | - | 464 (86.4) | 26 (5.6) | - | - |

| Traditional cookstove without ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 | - | 86 (16.0) | 6 (7.0) | 1.16 (0.47-2.87) | 0.752 |

| No | 535 (99.8) | 60 (11.2) | - | - | 451 (84.0) | 27 (6.0) | - | - |

| Kitchen without ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 193 (36.2) | 26 (13.5) | 1.45 (0.83-2.55) | 0.197 | 48 (9.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0.31 (0.40-2.29) | 0.248 |

| No | 340 (63.8) | 34 (10.0) | - | - | 471 (90.8) | 30 (6.4) | - | - |

| Wood or charcoal as a heating fuel | ||||||||

| Yes | 294 (56.1) | 38 (12.9) | 1.66 (0.91-3.00) | 0.096 | 477 (88.8) | 30 (6.3) | 1.25 (0.38-4.16) | 0.713 |

| No | 230 (43.9) | 20 (8.7) | - | - | 60 (11.2) | 3 (5.0) | - | - |

| Average hours of biomass exposure during the day (SD) | 2.15 (1.65) | 3.00 (2.45) | 1.35 (1.03-1.77) | 0.029 | 2.73 74.76) | 1.33 (0.58) | 0.55 (0.09-3.25) | 0.512 |

| Exposure to biomass while sleeping | ||||||||

| Yes | 110 (20.6) | 16 (14.6) | 1.58 (0.84-2.99) | 0.160 | 7 32/(1.3) | 0 | 1 | - |

| No | 424 (79.4) | 42 (9.9) | - | - | 529 (98.7) | 32 (6.1) | - | - |

| Critical Overcrowding * | ||||||||

| Yes | 159 (29.6) | 17 (10.7) | 0.93 (0.50-1.73) | 0.831 | 13 (2.42) | 2 (15.4) | 2.96 (0.67-13.07) | 0.152 |

| No | 378 (70.4) | 43 (11.4) | - | - | 524 (97.6) | 31 (5.9) | - | - |

| TB exposure | ||||||||

| Yes | 23 (4.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0.85 (0.19-3.77) | 0.833 | 17 (3.2) | 1 (5.9) | 0.95 (0.12-7.37) | 0.960 |

| No | 514 (95.7) | 58 (11.3) | - | - | 520 (96.8) | 32 (6.2) | - | - |

| ETS# exposure | ||||||||

| Yes | 169 (31.5) | 23 (13.61) | 1.39 (0.79-2.46) | 0.257 | 49 (9.2) | 5 (10.2) | 1.84 (0.68-4.95) | 0.228 |

| No | 368 (68.5) | 37 (10.1) | - | - | 486 (90.8) | 28 (5.76) | ||

| Educational attainment of the primary caregiver: | ||||||||

| Primary education | 223 (41.6) | 20 (9.0) | 1 | - | 59 (11.0) | 3 (5.1) | 1.57 (0.40-6.25) | 0.518 |

| Secondary education | 287 (53.5) | 40 (13.9) | 1.64 (0.93-2.9) | 0.086 | 258 (48.1) | 23 (8.9) | 2.95 (1.26-6.93) | 0.013 |

| Tertiary education | 26 (4.9) | 0 | - | - | 219 (40.9) | 7 (3.2) | ref | - |

| Mean Age (SD) | 2.53 (1.42) | 2.59 (1.22) | 1.03 (0.85-1.24) | 0.774 | 2.51 (1.52) | 2.55 (1.53) | 1.02 (0.81-1.28) | 0.886 |

| Preterm birth | ||||||||

| Yes | 47 (8.8) | 8 (17.0) | 1.77 (0.79-3.97) | 0.164 | 35 (6.5) | 3 (8.6) | 1.43 (0.41-4.94) | 0.574 |

| No | 490 (91.3) | 52 (10.6) | - | - | 501 (93.5) | 30 (6.0) | - | - |

| Low birth weight | ||||||||

| Yes | 42 (7.8) | 7 (16.7) | 1.65 (0.69-3.93) | 0.258 | 17 (3.3) | 2 (11.8) | 1.86 (0.41-8.53) | 0.422 |

| No | 495 (92.2) | 53 (10.7) | - | - | 492 (96.7) | 31 (6.3) | - | - |

| Never breastfed | 23 (4.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0.70 (0.16-3-16) | 0.645 | 38 (7.1) | 3 (7.9) | 1.36 (0.40-4.62) | 0.623 |

| Ever breastfed | 513 (95.7) | 58 (11.3) | - | - | 496 (92.9) | 30 (6.1) | - | - |

| Any dose of pneumococcal vaccine (records) | 317 (59.0) | 36 (11.4) | 1.04 (0.61-1.80) | 0.875 | 103 (19.2) | 2 (1.9) | 0.26 (0.06-1.08) | 0.064 |

| No pneumococcal vaccine | 220 (41.0) | 24 (10.9) | - | - | 434 (80.8) | 31 (7.1) | - | - |

| Regular or bad health reported by proxy | 63 (11.8) | 17 (27.0) | 4.19 (2.18-8.03) | 0.000 | 105 (19.6) | 17 (16.2) | 5.33 (2.59-11.00) | 0.000 |

| Good, very good or excellent health by proxy | 469 (88.2) | 39 (8.3) | - | - | 431 (80.4) | 15 (3.5) | - | - |

| Reference of asthma | ||||||||

| Yes | 22 (4.1) | 12 (54.6) | 11.87 (4.85-29.04) | 0.000 | 63 (11.7) | 14 (22.2) | 6.74 (3.19-14.21) | 0.000 |

| No | 514 (95.9) | 47 (9.14) | - | - | 474 (88.3) | 19 (4.0) | - | - |

| Preventive asthma treatment | ||||||||

| Yes | 75 (14.3) | 25 (33.3) | 6.08 (3.34-11.04) | 0.000 | 85 (16.1) | 13 (15.3) | 3.81 (1.82-7.96) | 0.000 |

| No | 451 (85.7) | 34 (7.5) | 444 (83.9) | 20 (4.5) | ||||

Number of inhabitants/number of rooms (excluding bathroom and kitchen)>3

Environmental tobacco smoke

Statistically significant results are shown in italic

The prevalence of hospital admissions in Temuco was 6.2%. The unadjusted and adjusted ORs for hospital admission in children exposed to HAP were 1.74 (95% CI 0.73-4.14; p = 0.210) and 1.16 (95% CI 0.44-3.06; p = 0.757), respectively.

Only one death was reported in the study. Specifically, in Bariloche, a five-month baby, born prematurely, with respiratory problems a few days before death (maternal report).

Perinatal Morbidity and Exposure to HAP

For each location, the association between perinatal morbidity and exposure to HAP as well as to other factors is shown in Table 5. The prevalence of perinatal morbidity in Bariloche was 12.4%. The unadjusted OR in pregnancies exposed to HAP was 1.59 (95% CI 0.72-3.50). After adjusting for the use of wood or charcoal as heating fuel, overcrowding, ETS exposure, pre-existing high blood pressure or hypertension, history of preeclampsia/eclampsia, smoking during pregnancy, high blood sugar or diabetes during the pregnancy, educational attainment, and maternal age, the adjusted OR was 1.41 (95% CI 0.50-3.97; p = 0.518).

Table 5.

Exposure to IAP and other factors, and its association with perinatal morbidity (bivariate analysis).

| Bariloche | Temuco | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Perinatal-morbidity (%) | OR (95%CI) | p | n (%) | Perinatal-morbidity (%) | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| All pregnancies | 356 | 44 (12.4) | 339 | 21 (6.5) | ||||

| Exposure to IAP | ||||||||

| Use of wood or charcoal as principal cooking fuel | ||||||||

| Yes | 63 (17.7) | 11 (17.5) | 1.59 (0.72-3.50) | 0.248 | 44 (13) | 6 (13.6) | 2.94 (1.07-8.03) | 0.036 |

| No | 293 (82.3) | 33 (11.3) | - | - | 295 (87.0) | 15 (5.1) | - | - |

| Traditional cookstove without ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 | - | 57 (16.8) | 5 (8.8) | 1.59 (0.56-4.54) | 0.384 |

| No | 355 (99.7) | 44 (12.4) | - | - | 382 (83.2) | 16 (5.7) | - | - |

| Kitchen without ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 139 (39.2) | 14 (10.1) | 0.72 (0.36-1.44) | 0.348 | 30 (9.2) | 1 (3.3) | 0.47 (0.06-3.65) | 0.472 |

| No | 216 (60.9) | 30 (13.89) | - | - | 295 (90.8) | 20 (6.8) | - | - |

| Wood or charcoal as a heating fuel | ||||||||

| Yes | 197 (56.9) | 24 (12.2) | 0.91 (0.46-1.78) | 0.782 | 306 (90.3) | 19 (6.23) | 1.03 (0.23-4.63) | 0.970 |

| No | 149 (43.1) | 19 (12.8) | - | - | 33 (9.73) | 2 (6.1) | - | - |

| Exposure to biomass while sleeping | ||||||||

| Yes | 36 (10.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0.59 (0.15-2.27) | 0.440 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (100) | 1 | - |

| No | 312 (89.7) | 39 (12.5) | - | - | 336 (99.7) | 20 (6.0) | - | - |

| Critical Overcrowding * | ||||||||

| Yes | 103 (28.9) | 11 (10.7) | 0.89 (0.42-1.87) | 0.750 | 7 (2.1) | 2 (28.6) | 6.57 (1.20-36.10) | 0.030 |

| No | 253 (71.1) | 33 (13.0) | - | - | 332 (97.9) | 19 (5.7) | - | - |

| ETS# exposure | ||||||||

| Yes | 106 (29.8) | 13 (12.3) | 1.09 (0.53-2.22) | 0.821 | 23 (6.8) | 1 (4.4) | 0.67 (0.09-5.20) | 0.698 |

| No | 250 (70.2) | 31 (12.4) | - | - | 314 (93.2) | 20 (6.4) | - | - |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| Primary education | 129 (36.3) | 15 (11.6) | 2.05 (0.32-19.96) | 0.375 | 39 (11.5) | 4 (10.3) | 2.02 (0.56-7.31) | 0.282 |

| Secondary education | 208 (58.6) | 28 (13.5) | 2.54 (0.25-16.71) | 0.503 | 168 (49.7) | 9 (5.4) | 1.01 (0.37-2..79) | 0.986 |

| Tertiary education | 19 (5.1) | 1 (5.6) | ref | - | 131 (39.8) | 7 (5.3) | - | - |

| Maternal age | 24.02 (6.10) | 26.12 (7.04) | ||||||

| >19 | 79 (22.3) | 12 (15.2) | 1.23 (0.57-2.62) | 0.601 | 62 (18.6) | 5 (8.2) | 1.48 (0.51-4.32) | 0.476 |

| >35 | 26 (7.3) | 2 (7.7) | 0.61 (0.14-2.72) | 0.518 | 43 (12.9) | 3 (7.0) | 1.24 (0.34-4.55) | 0.745 |

| 20-34 | 250 (70.4) | 30 (12.0) | ref | - | 228 (68.5) | 13 (5.7) | ref | - |

| Self-report of high blood sugar or diabetes | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 (2.8) | 1 (10.0) | 0.85 (0.10-6.95) | 0.881 | 40 (11.9) | 6 (15.0) | 3.31 (1.20-9.09) | 0.021 |

| No | 345 (97.2) | 43 (12.5) | 297 (88.1) | 15 (5.1) | ||||

| Self-report of high blood pressure or hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 43 (12.1) | 9 (20.9) | 2.28 (1-5.22) | 0.051 | 33 (9.8) | 7 (21.2) | 5.99 (2.20-16.31) | 0.000 |

| No | 313 (87.9) | 35 (11.2) | - | - | 303 (90.2) | 13 (4.3) | ||

| Self-report of other chronic conditions (pre-existence)¥ | ||||||||

| Yes | 30 (8.4) | 6 (20.0) | 1.94 (0.71-5.31) | 0.199 | 43 (12.7) | 4 (9.3) | 1.68 (0.54-5.24) | 0.374 |

| No | 326 (91.6) | 38 (11.7) | - | - | 296 (87.3) | 17 (5.8) | - | - |

| Self-report of high blood sugar or diabetes during pregnancy | ||||||||

| Yes | 19 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) | 1.40 (0.40-4.98) | 0.599 | 32 (9.4) | 4 (12.5) | 2.43 (0.76-7.72) | 0.133 |

| No | 337 (94.7) | 41 (12.2) | - | - | 307 (90.6) | 17 (5.6) | - | - |

| Self-report of hypertension during pregnancy | ||||||||

| Yes | 46 (13) | 9 (19.6) | 1.88 (0.82-4.31) | 0.134 | 20 (6) | 4 (20.0) | 5.32 (1.57-18.02) | 0.007 |

| No | 307 (87.0) | 34 (11.1) | - | - | 313 (94.0) | 14 (4.5) | - | - |

| Self-report of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | ||||||||

| Yes | 5 (1.6) | 1 (20.0) | 2.04 (0.22-18.87) | 0.528 | 7 (2.2) | 3 (42.9) | 15.96 (3.26-78.29) | 0.001 |

| No | 307 (98.4) | 34 (11.1) | - | - | 313 (97.8) | 14 (4.5) | ||

| Smoke during pregnancy | ||||||||

| Yes | 76 (21.4) | 12 (15.8) | 1.33 (0.63-2.82) | 0.452 | 46 (13.6) | 3 (6.5) | 1.06 (0.30-3.76) | 0.926 |

| No | 279 (78.6) | 32 (11.5) | - | - | 292 (86.4) | 18 (6.2) | - | - |

Number of inhabitants/number of rooms (excluding bathroom and kitchen)>3

Environmental tobacco smoke

Anemia, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Asthma, Depression/Psychiatric Illness, Epilepsy, Scleroderma, Gastritis/Ulcer, Hypothyroidism/Hyperthyroidism, Insulin resistance, Lupus, Purple, Antiphospholipid syndrome and other hematologic disorders, Sinusitis, Cancer

Statistically significant results are shown in italic

Temuco had a lower prevalence of perinatal morbidity (6.5%), but showed a significant association between pregnancies exposed to HAP and perinatal morbidity (unadjusted OR 2.94; 95% CI 1.07-8.03; p = 0.036). The adjusted OR for perinatal morbidity in pregnancies exposed to HAP was 3.11 (95% CI 0.86-11.32; p = 0.084) after adjusting for the use of wood or charcoal as heating fuel, ETS exposure, pre-existing high blood pressure or hypertension, pre-existing high blood sugar or diabetes, history of preeclampsia/eclampsia, smoking during pregnancy, high blood sugar or diabetes during the pregnancy, educational attainment, and maternal age.

As interaction between location and HAP was only found in the models in which LRTI was the outcome, we analyzed both sites jointly when perinatal morbidity was examined as the outcome of interest. We did not find a significant association between perinatal morbidity and HAP exposure (adjusted OR 2.10; 95% CI 0.93-4.74; p = 0.076).

In Temuco, one stillbirth was reported (sixth month of pregnancy; weight 420 grams); additional data related to this pregnancy were not available

Figure 1 shows all adjusted ORs for the associations between exposure to biomass fuels in the households with LRTI and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Figure 1.

Adjusted OR (95%CI) for LRTI events, LRTI hospital admissions and perinatal morbidity per country. Temuco (Chile) in red and Bariloche (Argentina) in blue.

Additional Analysis

We explored the variable of more than 200 hours/year of exposure to biomass fuel for cooking in the multivariate analysis, but did not find statistically significant results. The OR for LRTI was 1.25 (95% CI 0.70-2.22) for Bariloche and 1.20 (95% CI 0.75-1.93) for Temuco. For perinatal morbidity, the OR for Bariloche was 0.86 (95% CI 0.31-2.33) and for Temuco was 2.28 (95% CI 0.67-7.73).

Because Temuco had a prevalence of traditional cookstoves without chimney of 15.8%, we analyzed this variable as exposure, yielding an OR for LRTI of 1.29 (95% CI 0.70-2.40) and an OR of 1.05 (95% CI 0.21-5.21) for perinatal morbidity.

Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing the most exposed (use of wood or charcoal as the primary fuel) and the non-exposed (exclusive use of gas). These results reinforce the directionality of the results shown above, as demonstrated through smaller changes in the ORs and narrower confidence intervals.

Discussion

The present study explored the relation between LRTI and adverse pregnancy outcomes with HAP in Bariloche and Temuco. The results of this study found no significant association between the exposure and the two outcomes. Even though the association between LRTI and HAP in Temuco was higher compared to Bariloche, it was not significant (OR 1.87; 95% CI 0.98-3.55; p = 0.056).

While the association between perinatal morbidity and exposure to HAP was not significant, the association in Temuco was stronger and at the margin of statistical significance, with OR 3.11 (95% CI 0.86-11.32; p = 0.084).

Our results in Chile were consistent with several observational studies conducted in low and middle-income countries with higher prevalence of biomass fuel use. However, previously published studies have found an association between the exposure to solid fuel smoke and the occurrence of LRTI in children younger than five years of age and adverse pregnancy outcomes (Tielsch et. al., 2009, Ramesh Bhat et. al., 2012, Mahalanabis et. al., 2002, Lakshmi et. al., 2013, Amegah et. al., 2012).

One of the possible factors contributing to the different results in Bariloche and Temuco is the higher use of traditional cookstoves without chimney in Temuco. This may explain the stronger association between the use of biomass fuels for cooking and LRTI and perinatal morbidity. The protective effect of chimneys in traditional cookstoves has been explored in other studies (Boy et. al., 2002, Thompson et. al., 2011). Another possible factor is the varying levels of ambient air pollution (Sanhueza H et. al., 2006).

The little or no effect of cooking with biomass fuels in Bariloche and Temuco may be related to the lower levels of exposure compared to other studies, given by the absence of open fire cooking in the households included in the present study, and the high prevalence of cooking in ventilated rooms. For example, two case-control studies conducted in Brazil (Victora et. al., 1994, Fonseca et. al., 1996) studied populations with low exposure to HAP and also did not find a significant association with LRTI. In addition, Murray et al. (2012) have shown an ameliorating effect of room ventilation on HAP exposure.

To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the association between HAP and maternal and child health in the Southern Cone of Latin America. Our investigation reflects the actual use of biomass fuel in two cities from upper-middle income countries, which is very different from the patterns observed in poorer countries. These two Patagonian cities have a generalized use of biomass fuel for heating in fireplaces, high access to gas and a significant amount of households relying in biomass fuels for cooking. Interestingly, the characteristics of our population in terms of biomass fuel use and cookstove characteristics (vented combustion, the use of closed traditional cookstoves with chimneys, ventilated rooms) resemble the improvement interventions proposed by previous studies conducted in low-middle income countries (Smith et. al., 2010).

Some limitations of this study need to be discussed. First, given that the characteristics of the exposure and outcomes were obtained through interviews, participants are subject to recall bias. For instance, the exposure variable represents the average use of biomass fuel in the last five years and we cannot specify the temporal relationship between the exposure and the outcome. Also, in this regard the differences observed between study sites regarding LRTI events could be related to under-reporting of mild events in Bariloche, associated with the lower educational level of the caregivers. Previous studies have demonstrated that parents with lower educational level tend to provide less accurate reports, but become more reliable as the severity of the event increases (D'Souza-Vazirani et. al., 2005). Recall bias in our study could be also due to the seasonality of LRTI, particularly for Temuco as this data was collected throughout the winter season.

On the other hand, the interviews complemented with the direct observation of household kitchens in relation to the type of cookstove (traditional vs. clean) and ventilation (with and without chimney) which are known to be factors related to adverse health outcomes. Secondly, our exposure variable has not been used previously. In previous published studies (Regalado et. al., 2006, Ramirez-Venegas et. al., 2014, Ramirez-Venegas et. al., 2006), more than 200 hours per year of biomass fuel was used to define the threshold of exposure (Perez-Padilla et. al., 1996). Because we observed that households using more than 200 hours per year were also using gas as the primary fuel (for more hours than biomass), we decided to create a more conservative variable defining as principal fuel for cooking, the one with more hours per year of use. We believe this definition accurately reflects the reality in Temuco and Bariloche since the majority of households in these cities have access to clean fuels. Also, the results were similar and not significant with the two variables. Finally, both cities, particularly in Temuco, the general use of biomass for heating cannot be separated with one effect from the other, even though it was considered in the multivariate analysis.

In conclusion, our findings may support that cooking with biomass fuels in improved traditional cookstoves with ventilation appeared to have less adverse health outcomes than open fire, and provided support to expand the use of clean cookstoves in low resource settings. While the use of clean fuels is widespread in Bariloche and Temuco, families continue to rely on the use of biomass fuel for cooking. The use of biomass fuel for cooking, even in ventilated dwellings, may increase the risk of perinatal morbidity and LRTI. These findings have important implications in the future interventions aimed at reducing HAP in countries in which the use of gas and electricity have not yet completely replaced the use of biomass fuels in household cooking.

Supplementary Material

Practical Implications.

Despite the widespread availability of clean fuels in middle-income settings, many families still rely on the use of biomass fuel for cooking. The use of biomass fuel, even in ventilated dwellings, might increase the risk of perinatal morbidity and LRTI. These findings have important implications for the design of future interventions aimed at reducing HAP in countries, in which the use of gas and electricity have not fully replaced biomass fuels.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole with Federal funds from the United States National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. 268200900029C.

Special thanks to Luz Gibbons and Laura Gutiérrez for their help with the statistical analysis and data management, to Rebecca Kanter, Melissa Amyx and Diana Pham for the grammatical review and to Graciela Hanek and Jenny Ruedlinger Standen for their great field work and commitment.

References

- Amegah AK, Jaakkola JJ, Quansah R, Norgbe GK, Dzodzomenyo M. Cooking fuel choices and garbage burning practices as determinants of birth weight: a cross-sectional study in Accra, Ghana. Environmental health : a global access science source. 2012;11:78. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benguigui Y, López Antuñano FJ, Schmunis G, Yunes J. Respiratory Infections in Children. Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy E, Bruce N, Delgado H. Birth weight and exposure to kitchen wood smoke during pregnancy in rural Guatemala. Environmental health perspectives. 2002;110:109–114. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1078–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki TK. Burning issues: tackling indoor air pollution. Lancet. 2011;377:1559–1560. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'souza-Vazirani D, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM. Validity of maternal report of acute health care use for children younger than 3 years. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2005;159:167–172. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dherani M, Pope D, Mascarenhas M, Smith KR, Weber M, et al. Indoor air pollution from unprocessed solid fuel use and pneumonia risk in children aged under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:390–398. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca W, Kirkwood BR, Victora CG, Fuchs SR, Flores JA, et al. Risk factors for childhood pneumonia among the urban poor in Fortaleza, Brazil: a case--control study. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:199–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000. Assessing the Fit of the Model; pp. 143–202. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional De Estadística Y Censos. Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas. Vol. 2014. Buenos Aires: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional De Estadísticas. Censo de Población y Vivienda. Vol. 2014. Santiago de Chile: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kadir MM, Mcclure EM, Goudar SS, Garces AL, Moore J, et al. Exposure of pregnant women to indoor air pollution: a study from nine low and middle income countries. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2010;89:540–548. doi: 10.3109/00016340903473566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood BR, Gove S, Rogers S, Lob-Levyt J, Arthur P, et al. Potential interventions for the prevention of childhood pneumonia in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:793–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi PV, Virdi NK, Sharma A, Tripathy JP, Smith KR, et al. Household air pollution and stillbirths in India: analysis of the DLHS-II National Survey. Environ Res. 2013;121:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ACC, Katz J, Blencowe H, Cousens S, Kozuki N, et al. National and regional estimates of term and preterm babies born small for gestational age in 138 low-income and middle-income countries in 2010. The Lancet Global Health. 2013;1:e26–e36. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legros G, Havet I, Bruce N, Bonjour S. The energy access situation in developing countries. New York, NY: United Nations Development Progamme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EL, Brondi L, Kleinbaum D, Mcgowan JE, Van Mels C, et al. Cooking fuel type, household ventilation, and the risk of acute lower respiratory illness in urban Bangladeshi children: a longitudinal study. Indoor air. 2012;22:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2011.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanabis D, Gupta S, Paul D, Gupta A, Lahiri M, et al. Risk factors for pneumonia in infants and young children and the role of solid fuel for cooking: a case-control study. Epidemiology and infection. 2002;129:65–71. doi: 10.1017/s0950268802006817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Padilla R, Regalado J, Vedal S, Pare P, Chapela R, et al. Exposure to biomass smoke and chronic airway disease in Mexican women. A case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:701–706. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope DP, Mishra V, Thompson L, Siddiqui AR, Rehfuess EA, et al. Risk of low birth weight and stillbirth associated with indoor air pollution from solid fuel use in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:70–81. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh Bhat Y, Manjunath N, Sanjay D, Dhanya Y. Association of indoor air pollution with acute lower respiratory tract infections in children under 5 years of age. Paediatrics and international child health. 2012;32:132–135. doi: 10.1179/2046905512Y.0000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, Perez-Padilla R, Regalado J, Velazquez A, et al. Survival of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to biomass smoke and tobacco. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:393–397. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-568OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, Quintana-Carrillo RH, Velazquez-Uncal M, Hernandez-Zenteno RJ, et al. FEV1 decline in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with biomass exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:996–1002. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0720OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado J, Perez-Padilla R, Sansores R, Paramo Ramirez JI, Brauer M, et al. The effect of biomass burning on respiratory symptoms and lung function in rural Mexican women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:901–905. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-479OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein AL, Irazola VE, Bazzano LA, Sobrino E, Calandrelli M, et al. Detection and follow-up of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and risk factors in the Southern Cone of Latin America: the pulmonary risk in South America (PRISA) study. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza HP, Vargas RC, Mellado GP. Impacto de la contaminación del aire por PM10 sobre la mortalidad diaria en Temuco. Revista médica de Chile. 2006;134:754–761. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872006000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Bruce N, Balakrishnan K, Adair-Rohani H, Balmes J, et al. Millions dead: how do we know and what does it mean? Methods used in the comparative risk assessment of household air pollution. Annual review of public health. 2014;35:185–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Mccracken JP, Thompson L, Edwards R, Shields KN, et al. Personal child and mother carbon monoxide exposures and kitchen levels: methods and results from a randomized trial of woodfired chimney cookstoves in Guatemala (RESPIRE) Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology. 2010;20:406–416. doi: 10.1038/jes.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Mccracken JP, Weber MW, Hubbard A, Jenny A, et al. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1717–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Samet JM, Romieu I, Bruce N. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax. 2000;55:518–532. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.6.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LM, Bruce N, Eskenazi B, Diaz A, Pope D, et al. Impact of reduced maternal exposures to wood smoke from an introduced chimney stove on newborn birth weight in rural Guatemala. Environmental health perspectives. 2011;119:1489–1494. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielsch JM, Katz J, Thulasiraj RD, Coles CL, Sheeladevi S, et al. Exposure to indoor biomass fuel and tobacco smoke and risk of adverse reproductive outcomes, mortality, respiratory morbidity and growth among newborn infants in south India. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1351–1363. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, Fuchs SC, Flores JA, Fonseca W, Kirkwood B. Risk factors for pneumonia among children in a Brazilian metropolitan area. Pediatrics. 1994;93:977–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw T, White Johansson E, Hodge M. Pneumonia: The forgotten killer of children. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)/World Health Organization (WHO); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. A new look al an old problem. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2011. Household Cookstoves, Environment, Health, and Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics. Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Optimal feeding of low birthweight infants in low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucra S, Tapia V, Steenland K, Naeher LP, Gonzales GF. Association between biofuel exposure and adverse birth outcomes at high altitudes in Peru: a matched case-control study. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2011;17:307–313. doi: 10.1179/107735211799041869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.