Abstract

Background

Recently, long-acting injection (LAI) of second-generation antipsychotics has become a valuable strategy for the treatment of schizophrenia. However, few studies have compared the effects of different LAI antipsychotics on cognitive functions so far. The present study aimed to compare the influence of risperidone LAIs (RLAI) and paliperidone palmitate LAIs (PP) on cognitive function in outpatients with schizophrenia.

Methods

In this 6-month, open-label, randomized, and controlled study, 30 patients with schizophrenia who were treated with RLAIs were randomly allocated to the RLAI-continued group or the PP group. At baseline and 6 months, the patients were evaluated using the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) that was the primary outcome of the study. The Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptic drug treatment-Short form (SWNS), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the Drug-Induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale (DIEPSS) scores were secondary outcome variables and they were tested at the same time points.

Results

The two groups did not differ in terms of PANSS, DIEPSS, or SWNS total score changes. However, the BACS score for the attention and processing speed item showed higher improvement in the PP group than the RLAI group (p = 0.039).

Conclusions

The results of this preliminary study suggest that PPs may improve attention and processing speed more than RLAIs. Anyway, a replication in a larger and double-blind study is needed.

Trial registration

UMIN000014470. Registered 10 July 2014

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0883-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Risperidone long-acting injection, Paliperidone palmitate, Cognitive function, Efficacy, Subjective well-being

Background

Schizophrenia is a devastating disease that has a chronic or intermittent course with numerous relapses over time [1]. Relapses of schizophrenia are known to adversely affect many biological functions [2] and antipsychotic treatment is pivotal for preventing relapses [3]. Anyway, in clinical setting patients’ compliance to oral antipsychotics is often poor and difficult to maintain over time [4], resulting in a heavy impact on the risk of relapse [5].

Previous studies reported that several factors are related to the adherence to antipsychotic drugs, many of them are patient-related factors (e.g. symptom severity, illness insight, attitude to medication or subjective well-being), but there are also medication-related factors (e.g. side effects), and environment-related factors (e.g. therapeutic alliance) [6–9]. One possible approach to manage patient non-adherence is the use of long-acting injections (LAI) [10]. Many studies have reported remarkable improvements in psychiatric symptoms and/or a higher efficacy in preventing recurrence/relapse when patients with schizophrenia are treated with LAIs [11].

Among the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), the present study examined risperidone (RIS) LAIs (RLAI) and paliperidone (PAL) palmitate LAIs (PP) that was recently marketed in many countries. PP is an active metabolite of RIS, and they resemble each other in many aspects. However, they differ in some of their pharmacological features [12]. Indeed, previous clinical studies compared Oral-RIS and Oral-PAL and they reported some differences pertaining the effects on cognitive functions [13, 14]. The treatment of neurocognitive deficits is another key target of treatment [15], since deficits in neurocognitive functions are among the core symptoms of schizophrenia [16]. Although some trials investigating cognitive functions in patients treated with RLAI were performed, PP was never investigated in relation to that issue [17, 18]. No study directly comparing RLAI and PP was performed so far, neither comparing their effects on cognitive functions.

Accordingly, the present paper aims to compare the influence of RLAIs and PPs on cognitive functions using the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) score as the primary outcome. As secondary outcomes, we investigated the differences between the drugs on measures of psychiatric symptoms, extrapyramidal symptoms, and subjective well-being, which are relevant issues in regard to long-term LAI use and adherence to antipsychotics.

Methods

Study design and setting

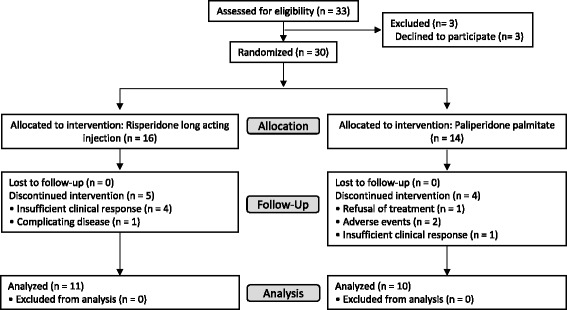

This was a 24-week pilot study using an open-label, parallel, randomized controlled design. It was conducted at Kansai Medical University Takii Hospital in Osaka from July 2014 to February 2015, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Kansai Medical University. After a full description of the study, all participants provided written informed consent prior to entering the study. We described this clinical trial according to the CONSORT 2010 guidelines. Enrollment, allocation, and follow-up of the study patients are depicted in the CONSORT diagram (Fig. 1). A supporting CONSORT 2010 checklist is available as supplementary information (see Additional file 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow of participants through the trial

Patients

All patients were at least 20 years old and had been diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria. The inclusion criteria were: 1) being during a non-acute phase of disease; 2) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of 120 or less; and 3) having received RLAI for 2 months or longer. The exclusion criteria were; 1) comorbid serious physical disorder; 2) active suicidal ideation; 3) history of attempted suicide; 4) history of drug or alcohol abuse; 5) mental retardation; 6) pregnancy; 7) current treatment with Oral-RIS, Oral-PAL; or 8) current treatment with multiple oral antipsychotics. Intelligence quotient was assessed using the Japanese Adult Reading Test (JART) [19]. For the duration of the study, subjects were allowed to take anticholinergic agents for new extrapyramidal symptoms, drugs for concomitant medical conditions if they started taking them before the enrollment in the study, low-dose sleep-inducing medications as needed, and other drugs considered to have no effect on the outcomes of interest. Additional administration of new antipsychotics, except for RLAI and PP, was not allowed during the study.

Procedures

Patients satisfying the inclusion criteria were randomized 1:1 to either the RLAI-continued group (hereafter, the RLAI group) or the PP group using the random number generation program of the SPSS software, version 21 (IBM SPSS, Tokyo, Japan). Patients in the RLAI group continued their treatment with the same dose of RLAI, and then underwent intramuscular injection into the gluteal muscles every 2 weeks. The dose was determined depending on each patient’s clinical status, with an upper limit of 50 mg/2 weeks. Patients in the PP group started the treatment by intramuscular injection into the deltoid or gluteal muscles. Their starting dose was equivalent to twice the dose of RLAI [20]. In the present study, a 4-week PP preparation was used. The dose was determined depending on each patient’s clinical status, with an upper limit of 150 mg/4 weeks.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the baseline-6 month change in BACS score between the RLAI group and the PP group. The secondary outcomes were the baseline-6 month changes in subjective well-being, psychiatric symptoms, and extrapyramidal symptoms between the two groups. Finally, the correlation between the changes in cognitive function and the changes in subjective well-being were evaluated.

The following assessments were performed at baseline and after 24 weeks: the BACS, Japanese version for cognitive function [16]; the Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptic drug treatment Short form (SWNS) [21, 22], Japanese version for subjective well-being; PANSS for clinical psychopathology [23]; and the Drug-Induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale (DIEPSS) for extrapyramidal symptoms [24].

The BACS is a tool for measuring cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia that consists of six items: verbal memory, working memory, motor speed, verbal fluency, attention, processing speed, and executive function [25]. Sufficient reliability and validity have been established for the BACS Japanese version [16]. In accordance with several previous studies using the BACS, the primary outcome measures were standardized into z-scores (the mean of healthy controls was set to zero, and the standard deviation was set to one) [25–27]. In the present study, the data for healthy controls were obtained from a previous study [28]. The BACS score was adjusted for age using age-matched controls to calculate the BACS-J z-scores for each schizophrenia patient in the present study.

The SWNS is a tool for measuring subjective well-being in patients with schizophrenia undergoing antipsychotic treatment. It consists of 20 questions covering five categories: mental function, self-control, emotional regulation, physical functioning, and social integration. Sufficient reliability and validity have been established for the SWNS Japanese version [29]. Each question is answered using a 6-point scale, with higher scores indicating higher subjective well-being.

Due to the open-label design of the study, neither patients nor raters were blind to patients’ group assignment.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed only for patients who completed all the 24 weeks of the study. The raw data collected at baseline and endpoint were used for the analysis. To ensure group comparability, baseline clinical characteristics were tested by t-tests or Pearson’s chi-square tests as appropriate. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess the change of BACS z-scores, SWNS scores, PANSS scores, DIEPSS, and antipsychotic dose in each treatment group using the baseline score as covariate. Only in the analysis of BACS z-score change the antipsychotic dose was used as covariate in addition to the baseline score because a significant correlation was observed between the BACS z-score and the antipsychotic dose. An exploratory Pearson’s correlational analysis was used to determine potential associations between changes in cognitive and subjective well-being scores. Analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 21.0 J (SPSS, Tokyo, Japan). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Thirty patients were allocated into the two groups (RLAI group, n = 16; PP group, n = 14) at the start of the study. During the study, 5 patients from the RLAI group and 4 from the PP group dropped out of the study (Fig. 1). Thus, the final analysis included the 21 patients who completed the study (11 in the RLAI group and 10 in the PP group). The clinical-demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. At baseline, the two groups did not differ significantly in age, onset, sex, diagnosis, PANSS total score, DIEPSS total score (sum of scores for items 1 to 8), total antipsychotics dose (chlorpromazine equivalent), or concomitant medications. Concomitant medications that a patient have started before the inclusion in the study were allowed to continue until the end of the study. During the 24-week study period, two patients from the PP group were also treated with low-dose ultrashort-acting hypnotics for new insomnia, and one patient from the same group was treated with an anti-hyperlipidemia drug for new hyperlipidemia. The patients were not treated with other drugs, including psychotropics.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients

| RLAI group | PP group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.4 ± 10.4 | 43.5 ± 11.8 | NS |

| Onset (years) | 29.5 ± 11.9 | 32.9 ± 11.7 | NS |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 7/4 | 4/6 | NS |

| Diagnosis (schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder) | 11/0 | 9/1 | NS |

| PANSS total score | 83.0 ± 19.9 | 78.1 ± 21.0 | NS |

| DIEPSS total score | 3.1 ± 3.1 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | NS |

| Total antipsychotics dosea | 432 ± 112.6 | 342 ± 94.7 | NS |

| Residence status (solitude/not solitude) | 4/7 | 3/7 | NS |

| Concomitant medication, n (%) | |||

| Anticholinergic drugs | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | NS |

NS no significant difference, RLAI risperidone long-acting injection, PP paliperidone palmitate, PANSS the positive and negative syndrome scale, DIEPSS the drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms scale

aChlorpromazine-equivalent dose

Cognitive function

At baseline, the RLAI and PP groups did not differ in any of the BACS z-scores. In the analysis of the changes in the BACS z-scores from baseline to the study endpoint, the attention and processing speed score showed higher improvement in the PP group compared to the RLAI group (p = .039; partial eta-squared = .228; 95%CI = −.79 to -.02; Table 2). There were no significant intergroup differences in the changes in the other scores, including the total score of each scale.

Table 2.

Change of primary outcome measures in risperidone long acting injection and paliperidone palmitate groups

| RLAI group | PP group | Difference in change between groups | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | p | Partial eta-squared | 95%CI | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| BACS | |||||||||||

| Verbal learning | 6 | 1.04 | .23 | 1.59 | −1.34 | .94 | .06 | 1.22 | .597 | .017 | −1.88 to 1.10 |

| Working memory | −2.12 | 1.15 | .12 | .77 | −1.10 | .91 | .26 | .62 | .412 | .040 | −1.09 to .470 |

| Motor function | −2.65 | .75 | .28 | .99 | −2.74 | 1.09 | .80 | 1.31 | .374 | .047 | −1.80 to .71 |

| Verbal fluency | −1.60 | .83 | .12 | .50 | −1.35 | .97 | .48 | .60 | .174 | .106 | −.93 to .18 |

| Attention and processing speed | −2.65 | 1.37 | .32 | .36 | −1.69 | 1.33 | .62 | .36 | .039* | .228 | −.79 to -.02 |

| Executive function | −2.03 | 2.80 | .63 | 2.69 | −.44 | 1.09 | −.13 | .99 | .171 | .107 | −1.76 to .34 |

| Composite score | −2.22 | .95 | .29 | .49 | −1.44 | .58 | .35 | .52 | .290 | .066 | −.80 to .25 |

*p < .05

Subjective well-being

No statistically significant differences were found for the all of baseline SWNS items score between the two groups. In the analysis of the changes in the SWNS scores from baseline to the endpoint, the emotional regulation score showed higher improvement in the PP group compared to the RLAI group (p = .034; partial eta-squared = .238; 95%CI = −5.90 to -.26; Table 3). There were no significant intergroup differences in the total score or in the changes in any of the other scores.

Table 3.

Change of secondary outcome measures in risperidone long acting injection and paliperidone palmitate groups

| RLAI group | PP group | Difference in change between groups | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | p | Partial eta-squared | 95%CI | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| SWNS | |||||||||||

| Total score | 79.09 | 19.93 | −.09 | 19.58 | 67.00 | 19.25 | 3.20 | 7.36 | .655 | .012 | −9.07 to 14.06 |

| Mental function | 16.00 | 4.52 | −.18 | 4.58 | 12.60 | 3.92 | .70 | 3.02 | .990 | < .001 | −3.74 to 3.69 |

| Self-control | 15.45 | 4.44 | 1.46 | 5.18 | 14.20 | 3.49 | .40 | 3.13 | .267 | .072 | −1.91 to 6.48 |

| Emotional regulation | 16.55 | 4.06 | −1.91 | 3.73 | 13.20 | 3.77 | 1.80 | 1.93 | .034* | .238 | −5.90 to -.26 |

| Physical functioning | 15.64 | 5.32 | −1.27 | 5.95 | 13.80 | 4.54 | .30 | 2.50 | .825 | .003 | −4.89 to 3.951 |

| Social integration | 15.36 | 5.63 | −.36 | 4.37 | 13.40 | 4.86 | .00 | 2.16 | .492 | .028 | −1.69 to 3.38 |

| PANSS | |||||||||||

| Total | 83.00 | 19.88 | −5.09 | 8.18 | 78.10 | 21.02 | −1.70 | 5.08 | .349 | .049 | −8.90 to 3.31 |

| Positive | 18.64 | 5.32 | −2.00 | 2.65 | 16.30 | 4.72 | −.30 | 2.00 | .222 | .082 | −3.39 to .84 |

| Negative | 21.73 | 5.14 | −.73 | 1.10 | 20.10 | 6.06 | .20 | 1.62 | .136 | .119 | −2.27 to .34 |

| General psychopathology | 42.64 | 10.88 | −2.36 | 5.45 | 41.70 | 11.05 | −1.60 | 2.50 | .732 | .007 | −4.39 to 3.14 |

| DIEPSS total | 2.55 | 2.60 | −.09 | .30 | 0.90 | 1.28 | .30 | 1.06 | .220 | .082 | −1.23 to .30 |

| Total antipsychotic dosea | 432 | 112.6 | −12.6 | 18.6 | 342 | 94.7 | −26.8 | 52.0 | .651 | .012 | −30.41 to 47.43 |

aChlorpromazine-equivalent dose, *p < .05

Changes in PANSS scores, DIEPSS total scores and dose of antipsychotic drugs

There were no significant differences in PANSS score, DIEPSS total score, or antipsychotic doses at baseline between the two groups. In addition, the changes in these scores from the baseline to endpoint did not differ between the two groups (Table 3).

Associations between changes in BACS scores and changes in SWNS scores

The changes in the SWNS total score did not correlate with the changes in any of the BACS z-scores. However, a correlation was found between improvements in the BACS score of attention and processing speed and the SWNS subscale of emotional regulation (r = .46, p = .037; Table 4). There were no significant correlations between any of the other BACS scores and any of the other subscales of the SWNS.

Table 4.

Correlations between changes in BACS scores and changes in SWNS scores

| BACS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VL | WM | MoF | VF | AP | EF | COM | ||

| SWNS | TS | −.03 | −.05 | .03 | −.24 | .29 | .17 | .08 |

| MeF | −.07 | .13 | .05 | −.19 | .24 | .33 | .21 | |

| SC | −.28 | .01 | .02 | −.27 | .06 | .16 | −.08 | |

| ER | .11 | −.15 | .23 | .09 | .46* | −.03 | .20 | |

| PF | −.13 | .03 | .14 | −.20 | .09 | .26 | .14 | |

| SI | .08 | −.05 | .03 | -.13 | .23 | .33 | .24 | |

BACS brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia, SWNS subjective well-being under neuroleptic drug treatment short form, VL verbal learning, WM working memory, MF motor function, VF verbal fluency, AP attention and processing speed, EF executive function, COM composite score, TS total score, MF mental function, SC self-control, ER emotional regulation, PF physical functioning, SI social integration

*p < .05

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present randomized study is the first attempt to evaluate changes in cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia during RLAI or PP treatment. The most clinically relevant finding obtained by this preliminary study is that patients who switch from RLAI to PP might have higher improvement in attention and processing speed than those who continue treatment with RLAL. Although the differences in effects on cognitive function observed between the two groups were very small, our results might have some implications for the treatment of schizophrenia.

To date, a number of studies have investigated the influence of pharmacological therapy on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. Many reports have demonstrated a slightly to moderately favorable influence of antipsychotic treatment on the cognitive function of patients with schizophrenia [30]. However, some studies have reported that cognitive function is negatively affected by standard- and high-dose antipsychotic treatment [31–34], antipsychotic polypharmacy [27], concomitant use of anti-Parkinson’s disease drugs [35], or concomitant use of benzodiazepines [36]. Thus, particular attention to drug doses and combinations is the first measure to avoid cognitive dysfunction. As a further step, the effects of different antipsychotics on cognitive function have been examined by several studies. Differences between the impact of SGAs and first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) on cognition have frequently been reported [37]. However, studies focused on the possible different effects of different SGAs found both negative [38, 39] and positive results [13, 40, 41]. Given that individual SGAs show different pharmacological profiles and that cognitive function consists of diverse domains, it seems likely that the effects on cognitive function may differ (even if slightly) among drugs [42].

Regarding the present study, the different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties between RLAIs and PPs should be considered. The greatest pharmacokinetic difference between the two compounds pertains to the PAL/RIS drug level ratio in the blood. PP works exactly as PAL, while the PAL/RIS blood ratio during RLAI treatment (both 25, 37.5, and 50 mg/14 days) was reported to be 2.4–3.0 [43] and much higher during Oral-RIS treatment (2 mg/day: 13.3, 4 mg/day: 11.5, 6 mg/day: 13.3). One possible reason for such a low PAL/RIS for RLAI is the lack of a first pass effect in the liver. This suggests that RLAI is a drug that more strongly reflects the influence of RIS compared to PP and Oral-RIS.

Under the pharmacodynamic point of view, PAL and RIS show many similarities in their affinities for receptors. However, their affinities for the alpha 2-adrenergic receptor are different, since PAL has a higher affinity than RIS for this receptor [12]. Animal studies have shown that the blockage of alpha 2-adrenergic receptors greatly affects the release of dopamine and noradrenaline from the medial prefrontal cortex [44]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that treatment with antidepressants with strong alpha 2-adrenergic receptor antagonistic activity (e.g. mirtazapine [45] or mianserin [46]) may improve cognitive function. Furthermore, many studies in humans, monkeys, and rodents have demonstrated that the noradrenergic nervous system, particularly through the alpha 2-adrenergic receptor, contributes to the regulation of attention [47]. Given that attention is a markedly disturbed cognitive domain in schizophrenia, the results of the present study deserve to be investigated by future studies. The results of a previous study [13] that compared Oral-RIS and Oral-PAL are poorly comparable with the present ones, since the reported pharmacokinetic differences among RLAIs, PPs, Oral-RIS, and Oral-PAL. In addition to these differences, the following issues should be considered: (1) the range of fluctuations in blood levels of Oral-RIS and Oral-PAL differ substantially (peak-to-trough fluctuation: 1.47 for Oral-PAL, 3.30 for Oral-RIS) [48]; (2) the frequency of sedation is higher with Oral-RIS than with Oral-PAL [49]; and (3) Oral-RIS may adversely affect working memory, a cognitive functional domain related to short-term memory [50].

In the present study, there were no differences between the two groups in the change in the total scores of the PANSS and DIEPSS. These results suggest similar efficacy and tolerability of RLAI and PP, consistently with previous studies [51–53].

The total score of the SWNS did not differ between the two groups, and there were no correlations between the changes in the total SWNS score and the BACS items. Thus, the subjective well-being of patients with schizophrenia did not differ between RLAI and PP, despite the higher improvement in some cognitive domains observed in the PP group. However, a correlation between emotional regulation (a SWNS subscale) and attention/processing speed improvement during treatment was found. Gross et al. assumed a model of emotion regulation that includes five phases and hypothesized that attention plays an important role in this process [54]. The event-related potentials measured by an electroencephalographic study and a functional magnetic resonance imaging study demonstrated a relationship between attention and emotional regulation [55, 56]. In addition, numerous reports have examined the dysfunctional interactions between attention and unpleasant stimuli, which are particularly interesting in regard to schizophrenia [57]. However, the current evidence appears still insufficient to state that improvements in attention during the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia can result in improvements of emotional regulation [57]. In addition, the SWNS subscales may be greatly affected by the total score and they may have low reliability [58]. Thus, further studies focused on this issue are needed.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size increases the risk of false negative findings. The lack of multiple-testing correction (e.g. Bonferroni correction) may also result in type I errors, but given the pilot nature of the present study, the results should be considered preliminary. Therefore, replication studies are needed, possibly with larger samples and through a randomized, double blind design. Second, the open-label design might have affected the results, since the expectations of patients or raters might have affected the assessments. However, the similar effects of the two drugs on symptomatology scores do not support this bias and the randomized design represents a point of strength. Third, we did not consider the drug blood level at the time of the cognitive assessment or of the other assessments. The drug blood level may have affected these evaluations [31], despite drug level fluctuations for LAIs are considerably smaller than for oral antipsychotics [59]. Finally, we did not strictly limit the use of anticholinergic agents, which may have an impact on cognitive function. However, only one patient in the RLAI group used anticholinergic agents, with probably no impact on the present results. Future studies should fix the timing of cognitive assessments and strictly control the use of concomitant medications.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the influence of RLAI and PP on cognitive functional domains and well-being. Compared to continue treatment with RLAI, switching from RLAL to PP therapy may have more favorable effects on attention and processing speed (as assessed using the BACS scale), which are important elements in cognitive function, although there were neither differences in symptom improvement according to the PANSS, nor in the frequency of extrapyramidal side effects. The higher improvement in attention and processing speed found in the PP group was associated with higher improvement in emotional regulation (accordingly to the SWNS). However, these results are preliminary and independent replication in larger samples is required before any definitive statement.

Abbreviations

BACS, brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia; DIEPSS, drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms scale; FGAs, first-generation antipsychotics; JART, japanese adult reading test; LAI, long-acting injection; PAL, paliperidone; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; PP, paliperidone palmitate; RIS, risperidone; RLAI, risperidone long-acting injection; SGAs, second-generation antipsychotics; SWNS, subjective well-being under neuroleptic drug treatment short form

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families who participated in this study. They also thank Drs. Katsunori Takase, Yukiko Saito, Hiroshi Mii, Satomi Matsuda and Nobuatsu Aoki, for data collection. We had no outside funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

YT and YK designed the study. YT, SS, NS, KN, MY, MK and TK collected clinical data and supervised the study. YK and AO carried out clinical and cognitive assessments and reviewed the manuscript. YT, CF, MK and AS interpreted the data and drafted the report. All of the authors contributed to and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing interests

We had no outside funding for this study. Dr. Takekita has received grant funding from Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (KAKEN 25861034) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and speaker’s honoraria from Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo Company and Ono Pharmaceutical within the past 3 years. Dr. Sunada has received speaker’s honoraria from Mochida Pharmaceutical and Eisai within the past 3 years. Dr. Nishida has received grant funding from Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (KAKEN 26860950) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and speaker’s honoraria from Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical and Shionogi within the past 3 years. Dr. Yoshimura has received grant funding from Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (KAKEN 22591305) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and speaker’s honoraria from Asahi Kasei Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo Company, Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Meiji-Seika Pharma, MSD K.K., Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company within the past 3 years. Dr. Kato has received grant funding from Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (KAKEN 23591684) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and speaker’s honoraria from Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Eli Lilly, MSD K.K., GlaxoSmithkline, Pfizer, Shionogi and Ono Pharmaceutical within the past 3 years. Dr. Kinoshita has received grant/research support or honoraria from, and been on the speakers of Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Otsuka, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo company, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, MSD K.K. Shionogi, Astellas Pharma, Eisai, GlaxoSmithkline and Ono Pharmaceutical. Dr. Serretti is or has been consultant/speaker for: Abbott, Abbvie, Angelini, Astra Zeneca, Clinical Data, Boheringer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Innovapharma, Italfarmaco, Janssen, Lundbeck, Naurex, Pfizer, Polipharma, Sanofi, Servier. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for this study has been approved by the institutional review board at Kansai Medical University (registration number kanirin-dai-hi 1305). The study is being conducted in Compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed signed consent to participate in the study will be obtained from all participants.

Additional file

CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial. (PDF 136 kb)

References

- 1.Lieberman JA. Atypical antipsychotic drugs as a first-line treatment of schizophrenia: a rationale and hypothesis. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 11):68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen NC, Liu D, Ziebell S, Vora A, Ho BC. Relapse duration, treatment intensity, and brain tissue loss in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal MRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):609–615. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12050674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W, Salanti G, Davis JM. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9831):2063–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mojtabai R, Lavelle J, Gibson PJ, Sohler NL, Craig TJ, Carlson GA, Bromet EJ. Gaps in use of antipsychotics after discharge by first-admission patients with schizophrenia, 1989 to 1996. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(3):337–339. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, Locklear J. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baloush-Kleinman V, Levine SZ, Roe D, Shnitt D, Weizman A, Poyurovsky M. Adherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a 6-month naturalistic follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1–3):176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karow A, Czekalla J, Dittmann RW, Schacht A, Wagner T, Lambert M, Schimmelmann BG, Naber D. Association of subjective well-being, symptoms, and side effects with compliance after 12 months of treatment in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatr. 2007;68(1):75–80. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCabe R, Bullenkamp J, Hansson L, Lauber C, Martinez-Leal R, Rossler W, Salize HJ, Svensson B, Torres-Gonzalez F, van den Brink R, et al. The therapeutic relationship and adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moritz S, Hunsche A, Lincoln TM. Nonadherence to antipsychotics: the role of positive attitudes towards positive symptoms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(11):1745–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhanji NH, Chouinard G, Margolese HC. A review of compliance, depot intramuscular antipsychotics and the new long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic risperidone in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(03)00109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray JA, Roth BL. The pipeline and future of drug development in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(10):904–922. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SW, Chung YC, Lee YH, Lee JH, Kim SY, Bae KY, Kim JM, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Paliperidone ER versus risperidone for neurocognitive function in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(5):267–274. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328356acad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki H, Gen K, Inoue Y, Hibino H, Mikami A, Matsumoto H, Mikami K. The influence of switching from risperidone to paliperidone on the extrapyramidal symptoms and cognitive function in elderly patients with schizophrenia: a preliminary open-label trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18(1):58–62. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2013.845218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green MF, Barnes TR, Danion JM, Gallhofer B, Meltzer HY, Pantelis C. The FOCIS international survey on psychiatrists’ opinions on cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;74(2–3):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneda Y, Sumiyoshi T, Keefe R, Ishimoto Y, Numata S, Ohmori T. Brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: validation of the Japanese version. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(6):602–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki H, Gen K. The influence of switching from oral risperidone to risperidone long-acting injection on the clinical symptoms and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2012;2(1):23–29. doi: 10.1177/2045125311430536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki H, Gen K. The influence of switching from haloperidol decanoate depot to risperidone long-acting injection on the clinical symptoms and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(5):470–475. doi: 10.1002/hup.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hori H, Noguchi H, Hashimoto R, Okabe S, Saitoh O, Kunugi H. IQ decline and memory impairment in Japanese patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(2):251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drug information of paliperidone palmitate. Interview form of XEPLION® Aqueous Suspension for IM Injection 7th edition [http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/interview/1/800155_1179409G1025_1_0http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/pack05_1F]. Accessed 3 Apr 2016.

- 21.Naber D. A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(Suppl 3):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naber D, Moritz S, Lambert M, Pajonk FG, Holzbach R, Mass R, Andresen B. Improvement of schizophrenic patients’ subjective well-being under atypical antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Res. 2001;50(1–2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inada T. Evaluation and Diagnosis of Drug-induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms: Commentary on the DIEPSS and Guide to its Usage. Tokyo: Seiwa Shoten; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2–3):283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hori H, Yoshimura R, Katsuki A, Hayashi K, Ikenouchi-Sugita A, Umene-Nakano W, Nakamura J. The cognitive profile of aripiprazole differs from that of other atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(6):757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori H, Yoshimura R, Katsuki A, Sugita AI, Atake K, Nakamura J. Switching to antipsychotic monotherapy can improve attention and processing speed, and social activity in chronic schizophrenia patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(12):1843–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaneda Y, Sumiyoshi T, Nakagome K, Numata S, Tanaka T, Ueoka Y, Omori T, Keefe R. The brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia Japanese version (BACS-J) Seishinigaku. 2008;50(9):913–917. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe M, Matsumura H. Reliability and validity of Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptic drug treatment Short form, Japanese version (SWNS-J) Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;6(7):905–912. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishara AL, Goldberg TE. A meta-analysis and critical review of the effects of conventional neuroleptic treatment on cognition in schizophrenia: opening a closed book. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(10):1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurai H, Bies RR, Stroup ST, Keefe RS, Rajji TK, Suzuki T, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and cognition in schizophrenia: analysis of the CATIE data. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(3):564–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Uchida H, Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, Kapur S, Pollock BG, Graff-Guerrero A, Menon M, Mamo DC. D2 receptor blockade by risperidone correlates with attention deficits in late-life schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(6):571–575. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181bf4ea3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodward ND, Purdon SE, Meltzer HY, Zald DH. A meta-analysis of cognitive change with haloperidol in clinical trials of atypical antipsychotics: dose effects and comparison to practice effects. Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1–3):211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeuchi H, Suzuki T, Remington G, Bies RR, Abe T, Graff-Guerrero A, Watanabe K, Mimura M, Uchida H. Effects of risperidone and olanzapine dose reduction on cognitive function in stable patients with schizophrenia: an open-label, randomized, controlled, pilot study. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):993–998. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogino S, Miyamoto S, Tenjin T, Kitajima R, Ojima K, Miyake N, Funamoto Y, Arai J, Tsukahara S, Ito Y, et al. Effects of discontinuation of long-term biperiden use on cognitive function and quality of life in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitajima R, Miyamoto S, Tenjin T, Ojima K, Ogino S, Miyake N, Fujiwara K, Funamoto Y, Arai J, Tsukahara S, et al. Effects of tapering of long-term benzodiazepines on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia receiving a second-generation antipsychotic. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;36(2):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodward ND, Purdon SE, Meltzer HY, Zald DH. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological change to clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(3):457–472. doi: 10.1017/S146114570500516X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keefe RS, Sweeney JA, Gu H, Hamer RM, Perkins DO, McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA. Effects of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone on neurocognitive function in early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1061–1071. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson M, Galderisi S, Weiser M, Werbeloff N, Fleischhacker WW, Keefe RS, Boter H, Keet IP, Prelipceanu D, Rybakowski JK, et al. Cognitive effects of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: a randomized, open-label clinical trial (EUFEST) Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(6):675–682. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08060806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purdon SE, Jones BD, Stip E, Labelle A, Addington D, David SR, Breier A, Tollefson GD. Neuropsychological change in early phase schizophrenia during 12 months of treatment with olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. The Canadian Collaborative Group for research in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(3):249–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bervoets C, Morrens M, Vansteelandt K, Kok F, de Patoul A, Halkin V, Pitsi D, Constant E, Peuskens J, Sabbe B. Effect of aripiprazole on verbal memory and fluency in schizophrenic patients : results from the ESCAPE study. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(11):975–982. doi: 10.1007/s40263-012-0003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desamericq G, Schurhoff F, Meary A, Szoke A, Macquin-Mavier I, Bachoud-Levi AC, Maison P. Long-term neurocognitive effects of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(2):127–134. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nesvag R, Hendset M, Refsum H, Tanum L. Serum concentrations of risperidone and 9-OH risperidone following intramuscular injection of long-acting risperidone compared with oral risperidone medication. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(1):21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franberg O, Marcus MM, Svensson TH. Involvement of 5-HT2A receptor and alpha2-adrenoceptor blockade in the asenapine-induced elevation of prefrontal cortical monoamine outflow. Synapse. 2012;66(7):650–660. doi: 10.1002/syn.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stenberg JH, Terevnikov V, Joffe M, Tiihonen J, Tchoukhine E, Burkin M, Joffe G. Effects of add-on mirtazapine on neurocognition in schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(4):433–441. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poyurovsky M, Koren D, Gonopolsky I, Schneidman M, Fuchs C, Weizman A, A, Weizman R. Effect of the 5-HT2 antagonist mianserin on cognitive dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia patients: an add-on, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13(2):123–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Sara SJ. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;10(3):211–223. doi: 10.1038/nrn2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheehan JJ, Reilly KR, Fu DJ, Alphs L. Comparison of the peak-to-trough fluctuation in plasma concentration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and their oral equivalents. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(7–8):17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, Samara M, Barbui C, Engel RR, Geddes JR, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reilly JL, Harris MS, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Adverse effects of risperidone on spatial working memory in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(11):1189–1197. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandina G, Lane R, Gopal S, Gassmann-Mayer C, Hough D, Remmerie B, Simpson G. A double-blind study of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in adults with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleischhacker WW, Gopal S, Lane R, Gassmann-Mayer C, Lim P, Hough D, Remmerie B, Eerdekens M. A randomized trial of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(1):107–118. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu DJ, Bossie CA, Sliwa JK, Ma YW, Alphs L. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral risperidone and risperidone long-acting injection in patients with recently diagnosed schizophrenia: a tolerability and efficacy comparison. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(1):45–55. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gross JJ. Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001;10(6):214–219. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferri J, Schmidt J, Hajcak G, Canli T. Neural correlates of attentional deployment within unpleasant pictures. Neuroimage. 2013;70:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hajcak G, MacNamara A, Foti D, Ferri J, Keil A. The dynamic allocation of attention to emotion: simultaneous and independent evidence from the late positive potential and steady state visual evoked potentials. Biol Psychol. 2013;92(3):447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strauss GP, Kappenman ES, Culbreth AJ, Catalano LT, Ossenfort KL, Lee BG, Gold JM. Emotion Regulation Abnormalities in Schizophrenia: Directed Attention Strategies Fail to Decrease the Neurophysiological Response to Unpleasant Stimuli. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;124(2):288–301. doi: 10.1037/abn0000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pazvantoglu O, Simsek OF, Aydemir O, Sarisoy G, Boke O, Ucok A. Factor structure of the Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptic treatment Scale-short form in schizophrenic outpatients: five factors or only one? Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68(4):259–265. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.807875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mannaert E, Vermeulen A, Remmerie B, Bouhours P, Levron JC. Pharmacokinetic profile of long-acting injectable risperidone at steady-state: comparison with oral administration. Encéphale. 2005;31(5 Pt 1):609–615. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(05)82420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.