Abstract

Background. Interventions are needed to alleviate memory difficulty in cancer survivors. We previously showed in a phase III randomized clinical trial that YOCAS©® yoga—a program that consists of breathing exercises, postures, and meditation—significantly improved sleep quality in cancer survivors. This study assessed the effects of YOCAS©® on memory and identified relationships between memory and sleep. Study design and methods. Survivors were randomized to standard care (SC) or SC with YOCAS©® . 328 participants who provided data on the memory difficulty item of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory are included. Sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. General linear modeling (GLM) determined the group effect of YOCAS©® on memory difficulty compared with SC. GLM also determined moderation of baseline memory difficulty on postintervention sleep and vice versa. Path modeling assessed the mediating effects of changes in memory difficulty on YOCAS©® changes in sleep and vice versa. Results. YOCAS©® significantly reduced memory difficulty at postintervention compared with SC (mean change: yoga=−0.60; SC=−0.16; P<.05). Baseline memory difficulty did not moderate the effects of postintervention sleep quality in YOCAS©® compared with SC. Baseline sleep quality did moderate the effects of postintervention memory difficulty in YOCAS©® compared with SC (P<.05). Changes in sleep quality was a significant mediator of reduced memory difficulty in YOCAS©® compared with SC (P<.05); however, changes in memory difficulty did not significantly mediate improved sleep quality in YOCAS©® compared with SC. Conclusions. In this large nationwide trial, YOCAS©® yoga significantly reduced patient-reported memory difficulty in cancer survivors.

Keywords: memory difficulty, cancer-related cognitive impairment, yoga, “chemobrain”, quality of life, cancer survivor

Introduction

Up to 75% of cancer patients experience some form of cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) during cancer treatments (eg, chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, hormone therapy), and this impairment persists for months or up to 20 years in 20% to 35% of survivors.1 CRCI commonly includes impairments in memory, executive function, attention, and concentration. Cancer survivors show altered brain structure and function consistent with impairments in CRCI domains.2-6 CRCI is associated with fatigue and other symptoms and has an overall negative impact on quality of life.7-9 It also leads to increased difficulty at work10,11 and reductions in social engagements and interferes with compliance with cancer treatments.12-14 Although intervention research for CRCI is emerging,15 there are currently no effective management approaches for CRCI used in standard clinical practice. The widespread prevalence of CRCI constitutes a significant clinical problem for which practical and innovative interventions need to be investigated. Research is also needed to assess whether improving memory might also help moderate and/or mediate improvements in sleep and other symptoms.

Research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of exercise, including yoga, on cognitive functioning and its association with fewer cognitive problems later in life among healthy adults, those at risk for neurodegenerative disease, and those with chronic conditions.16-21 Although yoga is a promising intervention, the effect of yoga on cognitive function has not been extensively evaluated in cancer patients and survivors. Galantino et al22 have evaluated yoga for cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in a case series, showing improved cognitive performance on objective tests of attention, executive function and memory, and perceived cognitive benefits. Other studies have showed improvements in other cancer-related symptoms, including fatigue, quality of life, affect, sleep, and psychological distress.23-30

Some forms of exercise (or physical activity) are safe and beneficial for cancer survivors, and yoga—a mode of exercise—has become increasingly popular in this population.31-35 Hatha yoga—the most widely used form of yoga—includes a sequence of meditative, breathing, and physical alignment exercises that require musculoskeletal engagement. Restorative yoga is characterized by a combination of meditative, breathing, and physical alignment exercises requiring the passive support of the body through the use of props and is designed to promote deep relaxation. We recently completed a phase III randomized clinical trial (RCT) through the University of Rochester Cancer Center (URCC) and Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) to investigate the effects of a combined Hatha and Restorative yoga program, Yoga for Cancer Survivors (YOCAS©® ), on sleep quality and efficiency in cancer survivors posttreatment. We previously reported greater improvements in global and subjective sleep quality, daytime dysfunction, wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, and medication use at postintervention compared with controls. Additionally, improvements in sleep latency, sleep duration, and daytime dysfunction were specific to controls, and medication use was reduced by 21% in yoga participants compared with 5% in controls. Therefore, we concluded that the improvements in global sleep quality in yoga participants may be related to reductions in daytime dysfunction in terms of less napping, less fatigue, and better sleep continuity, whereas any improvement in controls may be related to continued sleep medication.30,36 Here, we report a secondary data analysis investigating the effects of YOCAS©® on memory difficulty. We have included important covariates associated with memory function, including age, education, race, and ethnicity and also explored other covariates hypothesized to influence memory function in cancer survivors, including previous surgery, previous chemotherapy, previous radiation therapy, previous hormone therapy, and current hormone therapy. We also explored moderating effects of memory difficulty on postintervention sleep quality and vice versa and possible mediating effects of changes in memory on changes in sleep quality and vice versa.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a secondary analysis of a previously completed trial, of which the primary study results have been published previously.30 This study was registered with clinical trials.gov (NCT00397930). The URCC CCOP Research Base and 9 CCOPs conducted a nationwide, multicenter, RCT examining the efficacy of yoga for improving sleep quality in adult cancer survivors. Survivors were recruited in cohorts (n = 20-30), stratified by gender and baseline level of sleep disturbance (2 levels: ≤5 or >5 on an 11-point clinical symptom inventory scale anchored by 0 = no sleep disturbance and 10 = worst possible sleep disturbance), and randomly assigned to either a yoga or standard care (SC) control group at each CCOP. Group assignment was determined by a computer-generated random number table in blocks of 2 and 1:1 allocation ratio. The allocation was concealed from the coordinator until after the participant was registered by using a Web site that generated an e-mail to the research base and individual CCOP site. The study primary investigator and biostatistician were blinded to allocation. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the URCC CCOP Research Base and all participating CCOP recruitment sites, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Cancer survivors were recruited in 12 different US cities by 9 CCOPs from November 2006 to July 2009. Participants were enrolled between 2 and 24 months after completing surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy. For the current analyses, the eligibility criteria were not modified. Eligible survivors must (1) have a confirmed diagnosis of any type of cancer; (2) have undergone standard treatment for their cancer; (3) have completed all forms of standard treatment for their cancer between 2 and 24 months prior to consenting for the study and initiation of baseline assessments (continued treatment with hormones or monoclonal antibodies was allowed); (4) have persistent sleep disturbance (indicated by a response of 3 or greater on a clinical symptom inventory using an 11-point scale anchored by 0 = no sleep disturbance and 10 = worst possible sleep disturbance); (5) be able to read English; (6) be 21 years of age or older; (7) be able to give written informed consent; (8) not have maintained a regular personal practice of yoga within the 3 months prior to enrolling in the study or be actively planning to start yoga on their own; (9) not have a confirmed diagnosis of sleep apnea; (10) not be receiving any form of treatment for cancer, with the exception of hormonal or monoclonal antibody therapy; and (11) not have metastatic cancer.

Yoga Intervention

Yoga for Cancer Survivors, YOCAS©®, designed by researchers at the University of Rochester, is a combined Hatha and Restorative yoga program, which includes movement, breath, and awareness. A full description of the program is described in a previous publication,30 and key information is provided herein. Postures include seated, standing, transitional, and supine poses, with an emphasis on restorative poses, and the program was taught with modifications to address multiple levels of experience. The breathing exercises focused on regulation of breathing, and the awareness component included meditation instruction, visualization, and affirmation. The intervention was delivered in an instructor-taught group format over 8 sessions. Each session was 75 minutes, and sessions occurred twice a week during the late afternoon or evening at community-based sites, including yoga studios, community centers, and community oncology practices. Sessions were standardized across CCOP sites and included physical alignment postures, breathing, and mindfulness exercises. Instructors were Registered Yoga Alliance Instructors and each had to complete a standardized training session and was provided with a detailed YOCAS©® instructor manual and DVD. In addition, a coordinator at each CCOP completes the standardized training session and randomly observes YOCAS©® sessions to ensure proper content is taught.

Adherence to the intervention was good, with yoga participants attending an average of 6.5 of the 8 sessions. Yoga participants were also told that they could practice yoga that they learned from class outside class. Exercise contamination in the control group was minimal.

Measures

Memory Difficulty

Perceived memory difficulty was assessed using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI). The MDASI is a patient-reported clinical assessment tool used widely in cancer centers across the country. This measure, developed by Cleeland and colleagues, assesses multiple symptom outcomes for clinical and research use and applies to many different cancer types. It is sensitive to the symptoms that cancer patients experience and is sensitive to change in disease outcomes, quality of life, and performance status. A total of 13 core items are present in this measure, and each is assessed on a 11-point scale with 0 being not present to 10, as bad as you can imagine. This tool is designed to be used to assess a total symptom burden as well as individual systems related to cancer and cancer treatments. Impairment can be classified as none (score of 0), mild (score of 1-3), moderate (score of 4-6), and severe (score of 7-10) or used as a continuous outcome. The MDASI has been psychometrically validated with excellent test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity.37 In the current study, we focus on the perceived cognitive function item “difficulty remembering things” to assess perceived memory difficulty.

Sleep

Sleep quality was measured utilizing the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a psychometrically validated, patient-reported, 19-item instrument.33 We utilized the global sleep quality score for the moderation and mediation analyses involving sleep variables because this was the primary outcome measure in our previously published study.

Statistical Analyses

Main Analyses

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 and MPlus version 9.2. General linear modeling (GLM), controlling for age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, baseline memory, and baseline sleep score (PSQI) as covariates, was used to determine the group effect of YOCAS©® on memory difficulty as compared with controls. We included baseline PSQI as a covariate because sleep disturbance was an entry criteria for the main trial.

Age, memory difficulty, and sleep scores were treated as continuous variables, with gender, race, ethnicity, and education as categorical variables. In a second model, we added covariates of previous surgery, previous chemotherapy, previous radiation therapy, previous hormone therapy, and current hormone therapy as binary (ie, yes/no) covariates. In all cases, P < .05 was treated as significant.

Moderation Analyses

A moderator is a variable that influences the strength of the relationship between 2 other variables. Here, we assessed the influence of baseline sleep on postintervention memory by intervention condition and vice versa. To assess moderation of memory difficulty on sleep, we included age, mean-centered baseline memory difficulty score, mean-centered baseline PSQI, and mean-centered baseline memory difficulty score by intervention condition arm (YOCAS©® vs SC) interaction in our GLM model to evaluate moderation significance on PSQI score at postintervention.38

To assess moderation of sleep on memory, we included age, mean-centered baseline sleep, mean-centered baseline memory, and mean-centered baseline sleep score by intervention condition arm interaction in our GLM model to evaluate moderation significance on memory difficulty score at postintervention. IBM SPSS version 22 was used for these calculations.

Mediation Analyses

A mediator is a variable that explains partially or in its entirety a relationship between 2 other variables. Here, we assessed the effect of changes in memory on the efficacy of the intervention on sleep quality and vice versa. To determine the potential mediation effects of changes in reduced memory difficulty from preintervention to postintervention through YOCAS©® on improved sleep and vice versa, we performed path modeling on change scores for memory and sleep, to derive path coefficients including age as a covariate. We first conducted χ2 goodness-of-fit tests to determine model fit of memory mediating changes in sleep and vice versa. The memory mediation model included a direct path between intervention condition arm (YOCAS©® vs SC) and sleep, a path between intervention condition arm and memory, and a path between memory and sleep. Age was also included as a covariate. The sleep mediation model followed the same design, with a direct path between intervention condition arm and memory, a path between arm and sleep, and a path between sleep and memory. Age was also included as a covariate. Statistical significance of mediation was assessed through 95% confidence intervals (obtained from 10 000 bootstrap samples) for the indirect path coefficient from intervention condition to memory on sleep and vice versa.39 Mplus version 9.2 was used for the calculations. In all cases, P < .05 determined statistical significance.

Results

Participant Characteristics

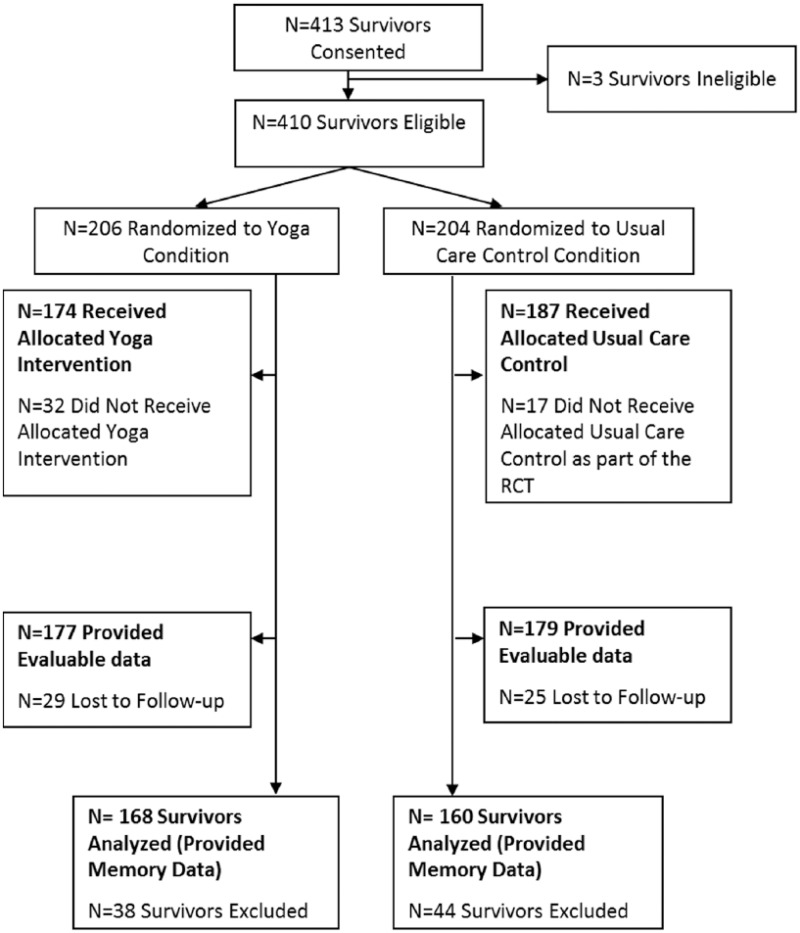

In the current study, 328 participants provided evaluable memory difficulty data at baseline and postintervention (Figure 1). Participants were predominantly female (96%) and 54 years of age, on average, ranging from 26 to 72 years old. Most of the participants had a diagnosis of breast cancer (77%; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram for secondary analysis.

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.a

| Characteristic | YOCAS©® Yoga (n = 168) | Standard Care Control (n = 160) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.24 (10.94) | 53.97 (8.72) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 160 (95.0%) | 154 (96.0%) |

| Male | 8 (5.0%) | 6 (4.0%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 161 (96%) | 147 (92%) |

| Black | 6 (3.5%) | 12 (7.5%) |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (3.0%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 149 (88.7%) | 152 (95.0%) |

| Unknown | 14 (8.3%) | 7 (4.4%) |

| Education | ||

| Partial high school | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| High school graduate | 26 (15.5%) | 31 (19.4%) |

| Partial college | 63 (37.5%) | 53 (33.1%) |

| College graduate (4 years) | 53 (31.5%) | 49 (30.6%) |

| Graduate degree | 25 (14.9%) | 26 (16.3%) |

| Menopausal status | ||

| Premenopausal | 24 (14.3%) | 24 (15.0%) |

| Perimenopausal | 15 (8.9%) | 16 (10.0%) |

| Postmenopausal | 119 (70.8%) | 111 (69.4%) |

| Not applicable or unknown | 10 (6.0%) | 9 (5.6%) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Breast | 124 (73.8%) | 127 (79.4%) |

| Hematological | 13 (7.7%) | 11 (6.9%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (2.4%) | 9 (5.6%) |

| Gynecological | 10 (6.0%) | 4 (2.4%) |

| Head and neck | 6 (3.6%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Lung | 5 (3.0%) | 4 (2.4%) |

| Genitourinary | 5 (3.0%) | 3 (2%) |

| Melanoma | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Previous surgery | ||

| Yes | 151 (89.9%) | 146 (91.3%) |

| No | 17 (10.1%) | 14 (8.8%) |

| Previous chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 123 (73.2%) | 109 (68.1%) |

| No | 45 (26.8%) | 51 (31.9%) |

| Previous radiation | ||

| Yes | 112 (66.7%) | 107 (66.9%) |

| No | 56 (33.3%) | 53 (33.1%) |

| Previous hormone therapy | ||

| Yes | 10 (6.0%) | 10 (6.3%) |

| No | 158 (94.0%) | 150 (93.8%) |

| Current hormone therapy | ||

| Yes | 80 (47.6%) | 93 (58.1%) |

| No | 88 (52.4%) | 67 (41.9%) |

| PSQI | 9.20 (3.30) | 8.98 (3.42) |

Abbreviations: PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Values are n (%) or mean (standard deviation).

Impact of Yoga on Memory Difficulty

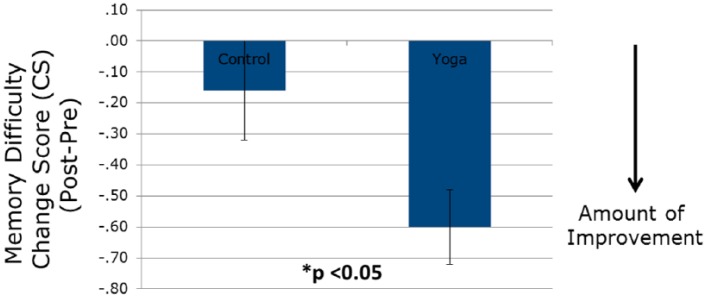

The average score on the MDASI memory item in the entire cohort was 3.03 at study baseline, indicating a mild level of difficulty in the overall population: 14% had no difficulty (score of 0), 51% had mild difficulty (score of 1-3), 22% had moderate difficulty (score of 4-6), and 13% had severe difficulty (score of 7-10; Table 2). Postintervention, those in the YOCAS©® group had a raw score decrease in memory difficulty of 0.60 units, whereas controls had a raw score decrease of 0.16 units (Table 3 and Figure 2). This represents a 19.2% improvement in the YOCAS©® group compared with a 5.4% improvement in controls; this postintervention group difference was statistically significant per the GLM model, controlling for relevant covariates, including age, race, gender, ethnicity, education, baseline memory, and baseline sleep score (PSQI) (P < .05). Additionally, the only covariate that was significantly and independently associated with postintervention memory score was baseline memory score. We also explored whether previous surgery, previous chemotherapy, previous radiation therapy, previous hormone therapy, and current hormone therapy were significant covariates in the GLM models. None of these was significant; however, previous chemotherapy showed a trend toward significance (P = .06), with chemotherapy exposure associated with increased reported memory difficulty. Overall, the Cohen’s D effect size of the impact of yoga over control was −0.24, indicating significantly more improvement in the YOCAS©® group compared with controls (P < .05).

Table 2.

Baseline Frequency and Severity of Perceived Memory Difficulty.

| Memory SI Score | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 47 (14.3%) |

| 1-3 | 168 (51.2%) |

| 4-6 | 72 (22.0%) |

| 7-10 | 41 (12.5%) |

Table 3.

Memory in YOCAS©® and Standard Care Control Groups Preintervention and Postintervention.a

| Memory SI | YOCAS©® Yoga | Standard Care Control |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3.11 (2.54) | 2.94 (2.65) |

| Postintervention | 2.51 (2.39) | 2.78 (2.55) |

| Change scoreb | −0.60 (1.55) | −0.16 (2.05) |

Values are mean (standard deviation).

P < .05.

Figure 2.

Change scores of YOCAS©® and standard care groups on perceived memory.

Moderation and Mediation Pathways: Testing Memory as the Moderator and Mediator on Sleep

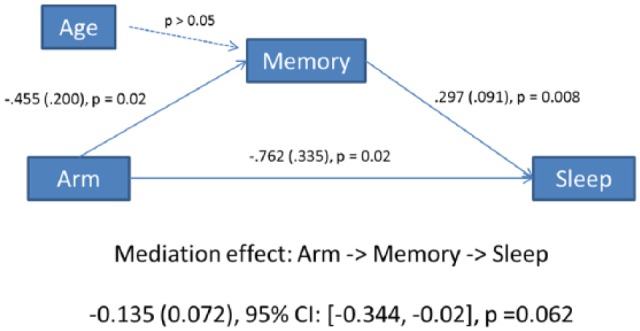

We decided to keep age as a covariate in the moderation and mediation pathway analyses because age is well known for association with cognitive difficulties, including memory difficulty, and the age range of participants in our study spanned 47 years. We did not find a significant moderating effect of baseline memory on postintervention PSQI (P > .05). For mediation, we assessed changes in memory mediating changes in sleep. In this model, the direct effect of the intervention on sleep (using the PSQI total change score) was −0.762 (P < .05; Figure 3), meaning that the YOCAS©® intervention improved sleep quality by 0.762 points compared with the SC control group. The direct effect of the intervention on memory was −0.455 points (P < .05), meaning that the intervention reduced memory difficulty by 0.45 points. The path estimate for the mediating effects of YOCAS©® on sleep via memory was −0.135points (P = .06); however, this was not significant.

Figure 3.

Path mediation model of memory mediation of YOCAS©® effects on sleep.

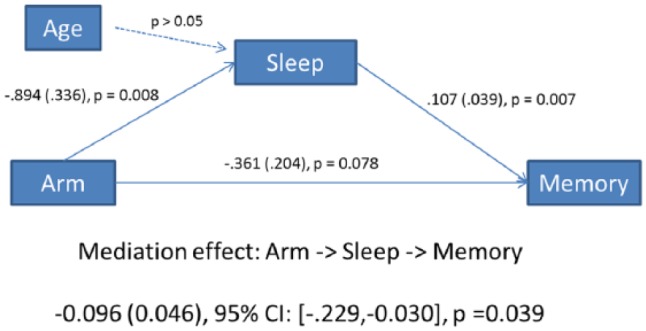

Moderation and Mediation Pathways: Testing Sleep as the Moderator and Mediator on Memory

We found a significant moderating effect of baseline sleep on postintervention memory difficulty (P < .05). For mediation, we assessed changes in sleep mediating changes in memory. In this model, the direct effect of the intervention on memory (using the memory difficulty change score) was −0.361 (P = .078; Figure 4), meaning that the YOCAS©® intervention improved memory by 0.361 points compared with the SC control group. The direct effect of the intervention on sleep was −0.894 points (P < .05), meaning that the intervention improved sleep by 0.894 points. The path estimate for the mediating effects of YOCAS©® on memory via sleep was −0.096 points (P = .039), suggesting that 26% of the improvement in memory was mediated through improving sleep.

Figure 4.

Path mediation model of sleep mediation of YOCAS©® effects on memory.

Discussion

This is the first study from a large RCT to show that YOCAS©® yoga—an intervention previously shown to improve global sleep quality—also significantly reduced perceived memory difficulty in cancer survivors. Whereas 85% of survivors reported some degree of memory difficulty, the most common rating was mild (51%), which is consistent with descriptions of complaints in survivors as often subtle. Baseline memory scores were significant independent predictors of postintervention memory difficulty. No other predictors that we assessed were significant; however, previous chemotherapy exposure showed a trend that is consistent with this type of treatment, as often reported as the most strongly associated with cognitive complaints. When we assessed moderation of memory on sleep, we did not find a significant relationship; however, baseline sleep did moderate the effects of reduced memory difficulty postintervention. Additionally, memory mediation did not significantly play a role in improving sleep; however, mediation by sleep did play a significant role in improving memory.

Overall, these results support the hypothesis that yoga has a positive effect on memory function in cancer survivors and reduces memory difficulty. Limited research has been conducted in this area. Sprod et al40 demonstrated that older cancer survivors who reported exercise during treatment had improved perceived memory function during and after treatment compared with survivors who did not exercise. One recent, noncontrolled feasibility study showed a positive effect of Tai Chi Chuan on multiple domains of cognitive function in cancer survivors, including memory, concentration, and attention.41 No large randomized controlled clinical trials assessing physical activity interventions for CRCI have been conducted, making the results of the current study novel.

The current study has a number of strengths. First, it consists of a large nationwide sample of cancer survivors, making the results generalizable to the US population. Moreover, assessment of the impact of yoga on memory was conducted using a rigorous, randomized controlled clinical trial design. Finally, perceived memory function was assessed, making the results relevant to the patients’ experience. Although these results need to be confirmed in future research, this is the first large study that suggests that yoga can improve perceived memory function in cancer survivors. This finding is supported by animal literature showing that physical activity can increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the brain—a region that is responsible for memory—and that chemotherapy damages by reducing neurogenesis. Numerous studies have shown that various forms of exercise in rodents improve memory, and most recently, exercise in mice was shown to improve chemotherapy-induced spatial memory impairments in animal models.42

The concept that improved sleep can help improve memory function is important, particularly if interventions that target sleep also improve memory and other cognitive functions. Previous studies have shown that improvements in cognitive function also improve other symptoms. For example, cognitive training of memory in cancer survivors also improved depression.43 Another cognitive training study showed improvements in anxiety and depression following similar cognitive training exercises.44 Our hypotheses need further testing. In an ongoing phase III trial, we are currently testing mediation hypotheses to further investigate the impact of yoga on sleep and memory difficulties and other co-occurring symptoms. In that study, we will investigate mediation and moderation effects of yoga on global sleep quality as well as sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep disturbance, daytime dysfunction, medication use, and subjective sleep quality. Improving memory and sleep could enhance overall quality of life and could have broad implications for improving activities of daily living, work-life balance, and social engagements.10,12,45

Although these results are encouraging, the study is not without limitations. First, while the results are based on a large nationwide RCT, the trial was not designed specifically to assess changes in cognition. Therefore, the assessment of cognition was limited to memory impairment and used a single-item self-report measure from the MDASI. A more sophisticated cognitive battery, with both objective and subjective assessments, is needed in future studies to determine if the impact of yoga is restricted to memory improvements or whether other domains of cognition may also be improved. Objective assessments of memory will also help support our findings. In the current analysis, we did not have data on the time since the last treatment, which is an important covariate to consider in future studies. Additionally, future studies need to incorporate more detailed treatment agent, dosage, frequency, and duration information to tease apart the impact of therapy on cognitive function and whether or not interventions for memory difficulty may work better in certain treatment settings. Our population included primarily breast cancer survivors, and the impact of yoga on memory, sleep, and other symptoms needs to be more thoroughly examined in those with other diagnoses. Finally, the mediation analyses need to be interpreted with caution because such analyses should use intermediate time points. In our analysis, we conducted the path analyses with change scores, and we lack the requisite temporal order of mediation, where the mediator is measured at a time between the intervention and postintervention assessment. However, overall, our results do indicate that for patients with sleep problems, yoga improved memory, at least partially via improved sleep.

The effects of YOCAS©® Yoga compared with SC on reducing memory difficulty were significant, positive, and conducted with a rigorous study design. More elaborate RCTs designed to specifically assess cognitive function outcomes in cancer survivors are needed to confirm these results. Moreover, further research is needed to better understand which components of yoga (ie, physical movements, meditation, and relaxation) are most important for improving memory function in cancer survivors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: K07CA168886, UCA037420, UCA037420 Supplement, and UG1CA189961.

References

- 1. Janelsins MC, Kesler SR, Ahles TA, Morrow GR. Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26:102-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kohli S, Griggs JJ, Roscoe JA, et al. Self-reported cognitive impairment in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:54-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Castellon SA, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Petersen L, Abraham L, Greendale GA. Neurocognitive performance in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy and tamoxifen. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:955-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schagen SB, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, Mellenbergh GJ, van Dam FS. Change in cognitive function after chemotherapy: a prospective longitudinal study in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1742-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kesler S, Janelsins M, Koovakkattu D, et al. Reduced hippocampal volume and verbal memory performance associated with interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in chemotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S109-S116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kesler SR, Kent JS, O’Hara R. Prefrontal cortex and executive function impairments in primary breast cancer. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1447-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hurria A, Zuckerman E, Panageas KS, et al. A prospective, longitudinal study of the functional status and quality of life of older patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1119-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hermelink K, Untch M, Lux MP, et al. Cognitive function during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: results of a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal study. Cancer. 2007;109:1905-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanford SD, Beaumont JL, Butt Z, Sweet JJ, Cella D, Wagner LI. Prospective longitudinal evaluation of a symptom cluster in breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:721-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, Davis RN, Meyers CA. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2292-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Bednarek HL, Schenk M. Short-term effects of breast cancer on labor market attachment: results from a longitudinal study. J Health Econ. 2005;24:137-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reid-Arndt SA, Yee A, Perry MC, Hsieh C. Cognitive and psychological factors associated with early posttreatment functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:415-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boykoff N, Moieni M, Subramanian SK. Confronting chemobrain: an in-depth look at survivors’ reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:223-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stilley CS, Bender CM, Dunbar-Jacob J, Sereika S, Ryan CM. The impact of cognitive function on medication management: three studies. Health Psychol. 2010;29:50-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fardell JE, Vardy J, Johnston IN, Winocur G. Chemotherapy and cognitive impairment: treatment options. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:366-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Subramanya P, Telles S. Effect of two yoga-based relaxation techniques on memory scores and state anxiety. Biopsychosoc Med. 2009;3:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarang SP, Telles S. Immediate effect of two yoga-based relaxation techniques on performance in a letter-cancellation task. Percept Mot Skills. 2007;105:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rocha KK, Ribeiro AM, Rocha KC, et al. Improvement in physiological and psychological parameters after 6 months of yoga practice. Conscious Cogn. 2012;21:843-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gothe N, Pontifex MB, Hillman C, McAuley E. The acute effects of yoga on executive function. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:488-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Uffelen JG, Chin APMJ, Hopman-Rock M, van Mechelen W. The effects of exercise on cognition in older adults with and without cognitive decline: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:486-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gothe NP, Kramer AF, McAuley E. The effects of an 8-week Hatha yoga intervention on executive function in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1109-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Galantino ML, Greene L, Daniels L, Dooley B, Muscatello L, O’Donnell L. Longitudinal impact of yoga on chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment and quality of life in women with early stage breast cancer: a case series. Explore. 2012;8:127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vadiraja HS, Rao MR, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of yoga program on quality of life and affect in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17:274-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vadiraja SH, Rao MR, Nagendra RH, et al. Effects of yoga on symptom management in breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga. 2009;2:73-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vadiraja HS, Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118:3766-3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galantino ML, Desai K, Greene L, Demichele A, Stricker CT, Mao JJ. Impact of yoga on functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:313-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sprod LK, Fernandez ID, Janelsins MC, et al. Effects of yoga on cancer-related fatigue and global side-effect burden in older cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mustian KM. Yoga as treatment for insomnia among cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review. Eur Med J Oncol. 2013;1:106-115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3233-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shneerson C, Taskila T, Gale N, Greenfield S, Chen YF. The effect of complementary and alternative medicine on the quality of life of cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:417-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chandwani KD, Ryan JL, Peppone LJ, et al. Cancer-related stress and complementary and alternative medicine: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:979213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beck SL, Schwartz AL, Towsley G, Dudley W, Barsevick A. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:140-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Janelsins MC, Mustian KM, Peppone LJ, et al. Interventions to alleviate symptoms related to breast cancer treatments and areas of needed research. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2011;(suppl 2):S2-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mustian K, Palesh O, Sprod L, et al. Effect of YOCAS©® yoga on sleep, fatigue, and quality of life: a URCC CCOP randomized, controlled clinical trial among 410 cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:9013. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. MacKinnon D. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sprod LK, Mohile SG, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Exercise and cancer treatment symptoms in 408 newly diagnosed older cancer patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:90-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reid-Arndt S, Matsuda S, Cox CR. Tai Chi effects neuropsychological, emotional, and physical functioning following cancer treatment: a pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fardell JE, Vardy J, Shah JD, Johnston IN. Cognitive impairments caused by oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy are ameliorated by physical activity. Psychopharmacology. 2012;220:183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kesler S, Hadi Hosseini SM, Heckler C, et al. Cognitive training for improving executive function in chemotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13:299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Von Ah D, Carpenter JS, Saykin A, et al. Advanced cognitive training for breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:799-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reid-Arndt SA, Hsieh C, Perry MC. Neuropsychological functioning and quality of life during the first year after completing chemotherapy for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:535-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]