Summary

Centrioles are fundamental and evolutionarily conserved microtubule-based organelles whose assembly is characterized by microtubule growth rates that are orders of magnitude slower than those of cytoplasmic microtubules. Several centriolar proteins can interact with tubulin or microtubules, but how they ensure the exceptionally slow growth of centriolar microtubules has remained mysterious. Here, we bring together crystallographic, biophysical, and reconstitution assays to demonstrate that the human centriolar protein CPAP (SAS-4 in worms and flies) binds and “caps” microtubule plus ends by associating with a site of β-tubulin engaged in longitudinal tubulin-tubulin interactions. Strikingly, we uncover that CPAP activity dampens microtubule growth and stabilizes microtubules by inhibiting catastrophes and promoting rescues. We further establish that the capping function of CPAP is important to limit growth of centriolar microtubules in cells. Our results suggest that CPAP acts as a molecular lid that ensures slow assembly of centriolar microtubules and, thereby, contributes to organelle length control.

Keywords: Centrioles, microtubules, CPAP/SAS-4, in vitro reconstitutions, human cells, X-ray crystallography

Highlights

-

•

CPAP's PN2-3 domain binds to an exposed site on β-tubulin at microtubule plus ends

-

•

CPAP tracks and caps microtubule plus ends in vitro

-

•

CPAP dampens microtubule growth in vitro

-

•

The capping function of CPAP limits centriolar microtubule growth in human cells

The mechanisms ensuring the extremely slow growth of centriolar microtubules remain elusive. Sharma, Aher, Dynes et al. demonstrate that human CPAP acts as a molecular lid that caps microtubule plus ends and dampens their elongation, thus contributing to centriole length control by ensuring slow processive assembly of centriolar microtubules.

Introduction

Centrioles are evolutionarily conserved organelles that are pivotal for the formation of cilia, flagella, and centrosomes, and are thus critical for fundamental cellular processes such as signaling, polarity, motility, and division (reviewed in Azimzadeh and Marshall, 2010, Bornens, 2012, Jana et al., 2014, Gönczy, 2012). Owing to their central role in such diverse cellular processes, centriole aberrations contribute to a range of severe human diseases, including ciliopathies, primary microcephaly, and cancer (reviewed in Nigg and Raff, 2009, Gönczy, 2015). Microtubules are the major constituent of centrioles and are arranged in a radial nine-fold symmetrical array, typically of triplet microtubules, which forms a barrel-shaped centriolar wall (reviewed in Azimzadeh and Marshall, 2010, Bornens, 2012, Jana et al., 2014, Gönczy, 2012). Centriolar microtubules are unique in exhibiting exceptionally slow growth rates of a few tens of nanometers per hour on average, and in being very stable after their formation (Kuriyama and Borisy, 1981, Chretien et al., 1997). Such properties likely contribute to setting centriole length, which is well conserved across evolution. The behavior of centriolar microtubules is in stark contrast to that of their cytoplasmic counterparts, which assemble up to four orders of magnitude faster and are highly dynamic (Kinoshita et al., 2001). The molecular mechanisms that impart the exceptional slow growth rate and stability of centriolar microtubules are not known.

Several centriolar proteins that can directly interact with tubulin and/or microtubules have been identified, including CEP120, CEP135, Centrobin, and CPAP (Gudi et al., 2011, Lin et al., 2013a, Lin et al., 2013b, Hsu et al., 2008). CPAP (SAS-4 in worms and flies) is of particular interest, since it is the only component among the ones listed above that is present and essential for centriole formation from worm to man (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009, Kirkham et al., 2003, Leidel and Gönczy, 2003). The importance of CPAP is further substantiated by the fact that homozygous mutations in the corresponding gene lead to autosomal recessive primary microcephaly, a devastating human disease with drastically reduced neuron numbers and, thus, brain size (Bond et al., 2005). Interestingly, CPAP overexpression induces overly long centrioles in human cells (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009), thus interfering with cell division (Kohlmaier et al., 2009). Together, these observations suggest that CPAP somehow regulates centriolar microtubule growth to produce proper centrioles. How this role is exerted at a mechanistic level remains elusive.

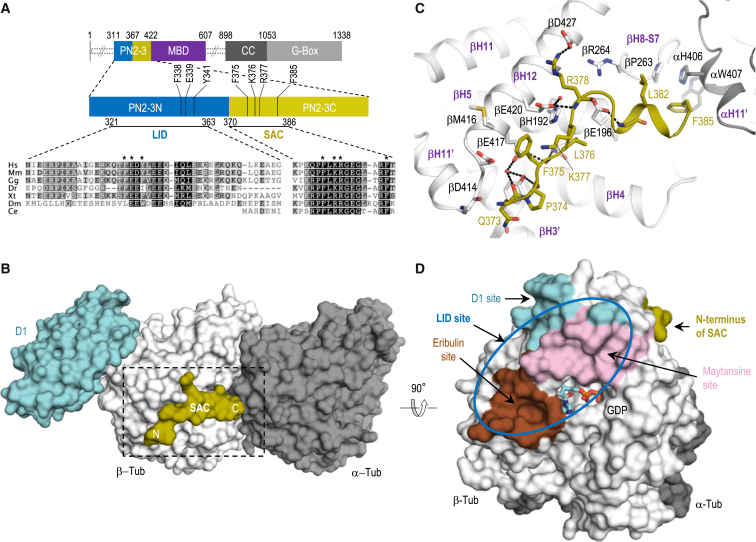

CPAP comprises a tubulin-binding domain (PN2-3), a positively charged microtubule-binding domain (MBD), a coiled-coil dimerization domain, and a C-terminal G box (Figure 1A). The PN2-3 domain is of prime interest as this region is highly conserved across evolution and found exclusively in CPAP/SAS-4 proteins. PN2-3 sequesters tubulin dimers and has been shown to destabilize microtubules both in vitro and in cells (Hsu et al., 2008, Cormier et al., 2009, Hung et al., 2004). How this observation can be reconciled with the presence of overly long centrioles upon CPAP overexpression, which is suggestive of the protein-enhancing centriolar microtubule elongation, has remained puzzling. Here, to elucidate the fundamental mechanism of action of CPAP/SAS-4 proteins, we set out to decipher how CPAP affects microtubules using structural, biophysical, and cell biological approaches. We first report a high-resolution structure of αβ-tubulin in complex with the PN2-3 domain of CPAP. This structural information guided the design of experiments aimed at understanding the key role of CPAP in regulating centriolar microtubule behavior. Using reconstitution experiments, we demonstrate that CPAP autonomously recognizes and tracks growing microtubule plus ends. There, CPAP suppresses microtubule polymerization and increases microtubule stability by inhibiting catastrophes and promoting rescues. We further establish that the PN2-3 domain of CPAP is critical in the cellular context to restrict the extent of centriolar microtubule elongation by acting as a molecular “cap.”

Figure 1.

Structure of the Tubulin-PN2-3 Complex

(A) Domain organization of human CPAP, with indication of amino acid numbers at domain boundaries. The PN2-3 region is shown magnified below, with residue conservation among CPAP/SAS-4 proteins in Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Gallus gallus, Danio rerio, Xenopus tropicalis, Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans. Black and gray shadings indicate different degrees of residue conservation. Blue and olive bars highlight the LID and SAC domains, respectively. Asterisks indicate residues that have been mutated in this study. MBD, microtubule-binding domain; CC, coiled coil.

(B) Overall view of the complex formed between PN2-3 (SAC residues in olive), αβ-tubulin (gray), and D1 (cyan). The N and C termini of SAC are indicated. The dashed box depicts the area shown in (C).

(C) Close-up view of the interaction between SAC (olive sticks) and tubulin (gray). Selected secondary structural elements of tubulin are labeled in bold purple letters. Residues at the tubulin-SAC interface are labeled in black and olive (SAC).

(D) Location of the D1 (cyan), eribulin (brown), and maytansine sites (pink) on β-tubulin. Note that eribulin binds to the vinca site on β-tubulin. The N terminus of SAC (olive) is shown. The blue oval represents the expected binding region of LID.

Results

Crystal Structure of the SAC Domain of CPAP in a Complex with Tubulin

To gain insight into the molecular mechanism of tubulin binding by CPAP/SAS-4 proteins, we sought to crystallize the PN2-3 domain of human CPAP in complex with tubulin (see Table S1 for all constructs generated in the course of this study). Extensive crystallization trials with complexes of tubulin and PN2-3 variants were not met with success. However, adding the β-tubulin-binding darpin (D1; Pecqueur et al., 2012) allowed us to solve the ternary complex formed between PN2-3, αβ-tubulin, and D1 (denoted the D1-tubulin-PN2-3 complex) to 2.2 Å resolution by X-ray crystallography (Figures 1A–1C and Table S2). As reported previously for other structures, the D1 molecule was bound at the tip of β-tubulin in the D1-tubulin-PN2-3 complex structure, a location involved in longitudinal tubulin-tubulin contacts within microtubules (Pecqueur et al., 2012). In addition, we found electron densities for residues 373–385 of PN2-3, which correspond to the evolutionarily conserved SAC domain of CPAP (for “Similar in SAS-4 and CPAP”; Leidel and Gönczy, 2003, Hsu et al., 2008, Kitagawa et al., 2011) (Figure 1B). In the PN2-3-tubulin-D1 complex structure, we found that SAC residues are engaged with both α- and β-tubulin subunits without affecting the overall conformation of the dimer (root-mean-square deviation of tubulin in the tubulin-D1 [PDB: 4DRX] and PN2-3-tubulin-D1 complex structures: 0.49 Å over 760 Cα atoms). The SAC-binding site on tubulin is shaped by hydrophobic and polar residues of helices αH11′, βH3′, βH5, and βH12, and loops βH8-S7 and βH11′-H12 (Figure 1C).

The SAC-tubulin interaction is characterized by an extensive water and non-water-mediated hydrogen-bonding network, as well as by hydrophobic contacts established between both main-chain and side-chain atoms of SAC and tubulin residues. Prominent SAC side-chain contacts involve Phe375 (βAsp414, βMet416, βGlu417, βGlu420), Leu376 (βHis192, βQln193, βGlu196), Lys377 (βGlu420), Arg378 (βGlu420, βAsn426), and Phe385 (αH406, αTrp407, βPro263). Pull-down experiments had implicated Lys377 and Arg378 in tubulin binding (Hsu et al., 2008), and our findings reveal the structural basis for their importance in this interaction.

Atomic Model of the Interaction of Tubulin and PN2-3

Previous studies suggested that PN2-3 inhibits exchange of the nucleotide on β-tubulin and that residues situated N-terminal to SAC also interact with tubulin (Cormier et al., 2009, Hsu et al., 2008, Hung et al., 2004). The D1-PN2-3-tubulin structure revealed that the N terminus of SAC is located close to the D1-binding site at the tip of β-tubulin (Figure 1D). We therefore reasoned that the presence of D1 might hinder access of this region of CPAP to its binding site. Accordingly, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments demonstrated that whereas PN2-3 bound tubulin with an equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of 47 ± 6 nM, the affinity of PN2-3 for tubulin-D1 dropped one order of magnitude (Figure 2A). Likewise, eribulin and maytansine, two drugs that bind near the D1- and nucleotide-binding site, and which also inhibit longitudinal tubulin-tubulin contacts in microtubules (Pecqueur et al., 2012, Prota et al., 2014, Alday and Correia, 2009), significantly impaired the affinity of PN2-3 for tubulin (Figure 2A). We conclude that the N-terminal part of PN2-3 binds to a site on the tip of β-tubulin engaged in longitudinal tubulin-tubulin interactions (Cormier et al., 2009); we therefore named this putative domain “LID”. To test whether the hydrolysis state of the exchangeable nucleotide bound to β-tubulin is important for tubulin-PN2-3 complex formation, as previously suggested for PN2-3 of Drosophila DmSAS-4 (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2012), we performed additional ITC experiments. As shown in Figure S1, we found similar KD values for the interaction between human CPAP PN2-3 and guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-, guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-, or GMPCPP-tubulin (maximal difference of 1.3-fold). We conclude that the hydrolysis state of the nucleotide bound to β-tubulin has at most a minor effect on tubulin-PN2-3 complex formation.

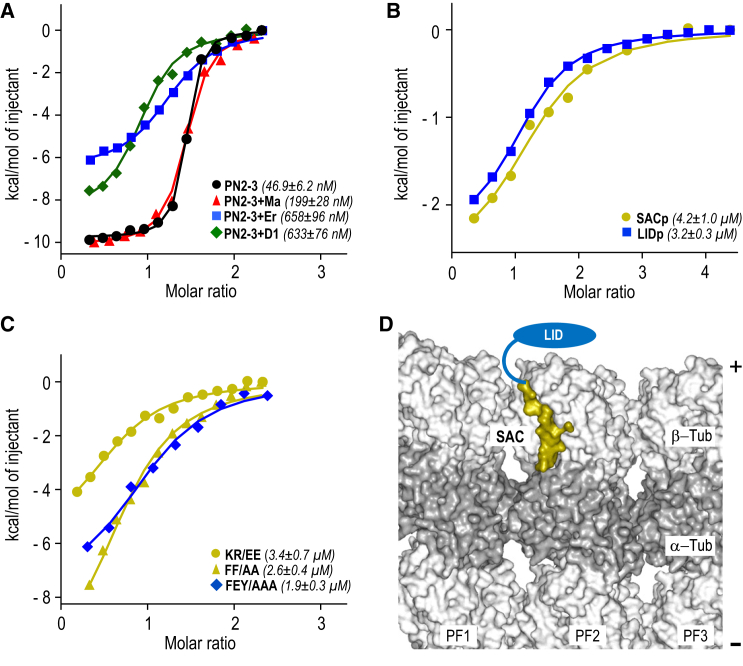

Figure 2.

Interactions of PN2-3 with Tubulin and Microtubules

(A–C) ITC analysis of interactions between indicated PN2-3 variants and tubulin. D1, DARPin; Er, eribulin; Ma, maytansine. Note that eribulin and maytansine bind to the vinca site and maytansine site on β-tubulin, respectively (Gigant et al., 2005, Prota et al., 2014, Smith et al., 2010).

(D) Binding of SAC (olive surface representation) and LID (schematically represented by a blue oval) in the context of a microtubule plus end, with three protofilaments (PF1–PF3) being represented. Light-gray surface representation, β-tubulin; dark-gray surface representation, α-tubulin. The plus (+) and minus (−) ends of the microtubule are indicated on the right.

To assess whether SAC and LID can bind tubulin independently, we generated two corresponding peptides, SACp and LIDp, and analyzed their tubulin-binding properties by ITC. KD values in the low micromolar range were obtained for the interactions between tubulin and either SACp or LIDp (Figure 2B). To investigate the importance of selected SAC and LID residues for tubulin binding, we conducted further ITC experiments with mutant variants of the PN2-3 domain. Mutation of the tubulin-interacting SAC residues Lys377 and Arg378 to glutamic acid (KR/EE), or of Phe375 and Phe385 to alanine (FF/AA), reduced the affinity of PN2-3 for tubulin by two orders of magnitude (Figure 2C; compare with wild-type PN2-3 in Figure 2A). We also tested a PN2-3 mutant in which three residues in a conserved region of LID (Phe338, Glu339, Tyr341; Figure 1A) were simultaneously mutated to alanine (FEY/AAA), and also in this case obtained a KD in the low micromolar range (Figure 2C).

These results suggest that both SAC and LID can bind independently to tubulin with low micromolar affinities, and that they cooperate to give rise to a ∼100-fold tighter interaction with tubulin when present together. To test whether SAC and LID could bind in the context of microtubules, we used an atomic model of a microtubule based on a cryoelectron microscopy reconstruction at 3.5-Å resolution (Zhang et al., 2015). Interestingly, this analysis showed that both SAC and LID binding interfaces are located on the outer surface, at the distal tip of the microtubule, which has exposed β-tubulin subunits (Figure 2D). This result indicates that CPAP could specifically target microtubule plus ends via its PN2-3 domain.

CPAP Tracks Growing Microtubule Plus Ends In Vitro

To test the idea that CPAP targets microtubule plus ends, we performed in vitro reconstitution experiments whereby dynamic microtubules were grown from GMPCPP-stabilized seeds and imaged using a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy-based assay (Bieling et al., 2007, Montenegro Gouveia et al., 2010). Since purified full-length CPAP was insoluble in our hands, we engineered a soluble chimeric protein in which the PN2-3-MBD moiety was fused to the leucine zipper domain of the yeast transcriptional activator GCN4 (O'Shea et al., 1991) to mimic the dimerization imparted by the endogenous coiled-coil domain of CPAP (Zhao et al., 2010), which is required for CPAP function in centriole duplication (Kitagawa et al., 2011), as well as to GFP (the resulting protein has been dubbed CPAPmini; Figures 3A and S2A).

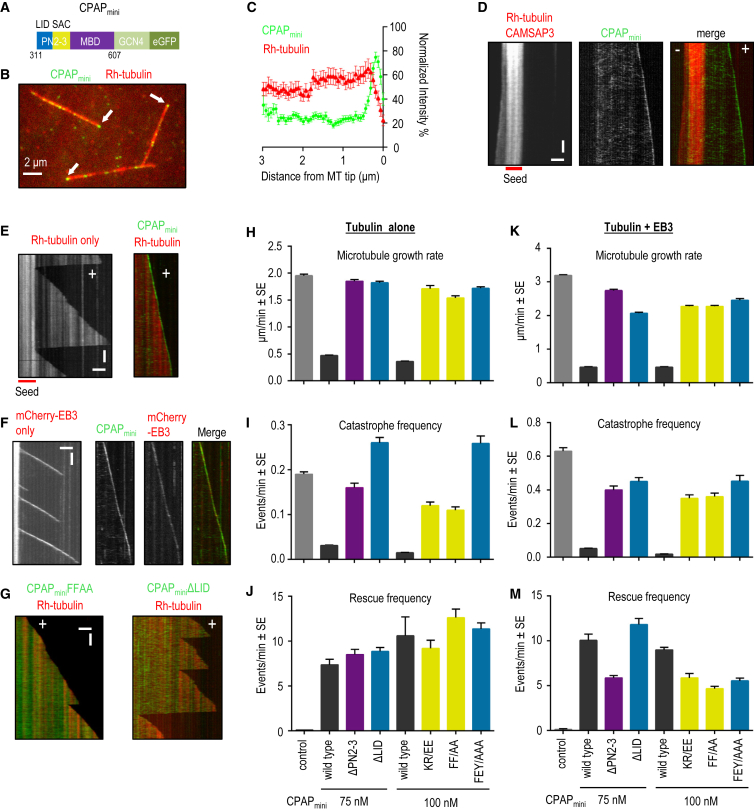

Figure 3.

Effects of CPAPmini on Dynamic Microtubules

(A) Schematic of CPAPmini construct.

(B) Single frame of a time-lapse movie of rhodamine (Rh)-labeled microtubules growing from rhodamine-GMPCPP seeds in the presence of CPAPmini. Arrows point to CPAPmini microtubule tip accumulation.

(C) Normalized mean intensity profiles for CPAPmini and rhodamine-tubulin obtained from 30 microtubules. Error bars represent SEM.

(D) Kymographs of microtubule growth at the plus (+) and minus (−) end from a rhodamine-GMPCPP seed with 50 nM mCherry-CAMSAP3 and 100 nM CPAPmini.

(E) Kymographs of microtubule plus-end dynamics with rhodamine-tubulin alone or together with 100 nM CPAPmini.

(F) Kymographs of microtubule plus-end dynamics with 20 nM mCherry-EB3 alone or together with 100 nM CPAPmini.

(G) Kymographs of microtubule plus-end dynamics with rhodamine-tubulin and 100 nM of the two indicated CPAPmini variants.

(H–M) Microtubule plus-end growth rate, catastrophe frequency, and rescue frequency in the presence of rhodamine-tubulin alone or together with 20 nM mCherry-EB3 and 100 nM of the indicated CPAPmini variants. ∼100–200 microtubule growth events from two to four independent experiments were analyzed per condition. Error bars represent SEM.

Scale bars in (D–G) represent 2 μm (horizontal) and 60 s (vertical). See also Figure S2 and Table S1.

We found that CPAPmini bound weakly to the microtubule lattice; importantly, in addition, we found that CPAPmini localized to, and tracked, one end of dynamic microtubules specifically (Figures 3B–3E). We determined that CPAPmini bound the plus end of microtubules, distinguished as such because it is negative for the minus-end targeting protein CAMSAP3 (Figure 3D) (Jiang et al., 2014). CPAPmini co-localized at growing microtubule tips with the plus-end tracking protein EB3 (Figure 3F). However, in contrast to EB3, the plus-end accumulation of which critically depends on microtubule growth (Bieling et al., 2007, Montenegro Gouveia et al., 2010), CPAPmini was enriched at one end of GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules even when soluble tubulin was present at a concentration insufficient for microtubule elongation (5 instead of 15 μM tubulin; Figure S2B). These data reveal that microtubule growth is not required for plus-end recognition by CPAPmini. In the absence of soluble tubulin, CPAPmini localized along the entire length of GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules (data not shown), indicating that the interaction of CPAPmini with soluble tubulin suppresses its binding to the microtubule lattice. Overall, we conclude that CPAPmini is an autonomous microtubule plus-end tracking protein.

CPAP Promotes Slow and Processive Microtubule Growth In Vitro

We set out to determine the impact of CPAPmini on microtubule dynamics. Strikingly, we found that CPAPmini strongly reduced the rate of microtubule growth (Figures 3E and 3H). This effect could not be explained by tubulin sequestration, because the concentration of CPAPmini in these experiments (75–100 nM) was much lower than that of tubulin (15 μM). Furthermore, CPAPmini dramatically reduced the frequency of catastrophes and promoted rescues, together leading to highly processive microtubule polymerization (Figures 3E, 3I, and 3J). This effect was also observed in the presence of EB3, despite the fact that EB3 itself causes a ∼1.5-fold increase in microtubule growth rate and a ∼3-fold increase in catastrophe frequency (Figures 3F and 3K–3M). To test whether the artificial dimerization domain of GCN4 in CPAPmini has an influence on microtubule dynamics, we purified a CPAP construct that contains the endogenous coiled coil (CPAPlong; Figures S2A and S2C). Although CPAPlong had a higher propensity for degradation and aggregation, it also bound to microtubule plus ends, very similarly to CPAPmini, and had a similar effect on microtubule dynamics: it reduced both the growth rate and the catastrophe frequency, and increased the rescue frequency (Figures S2D–S2G). These data demonstrate that GCN4 links CPAPmini polypeptide chains in a fashion similar to that of the endogenous coiled-coil domain.

Next, we tested the effect of mutations that disrupt either the tubulin-SAC (KR/EE, FF/AA) or the tubulin-LID interaction (ΔLID, FEY/AAA) on the ability of CPAPmini to regulate microtubule plus-end dynamics (Figures 1A and S2A). We found that all four mutants abrogated tip enrichment, as well as the effects on microtubule growth and catastrophes (Figures 3G–3L and S2H). In contrast, all mutants, as well as the dimeric version of MBD alone (ΔPN2-3), were still able to bind to the microtubule lattice and induce rescues to an extent similar to that of wild-type CPAPmini (Figures 3G–3M). This result suggests that the MBD has microtubule-stabilizing properties. To further assess the mechanism underlying the activity of CPAPmini, we investigated how its concentration affects microtubule dynamics. As mentioned above, at 75 nM of CPAPmini, though not at lower concentrations, both the microtubule growth rate and the catastrophe frequency were strongly reduced (Figures 3H–3L, 4A, and 4B). A 4-fold increase in concentration of CPAPmini had little additional effect on the microtubule growth rate and catastrophe frequency, indicating that the effect of CPAPmini on microtubule elongation in vitro saturates at ∼75 nM (Figures 4A and 4B).

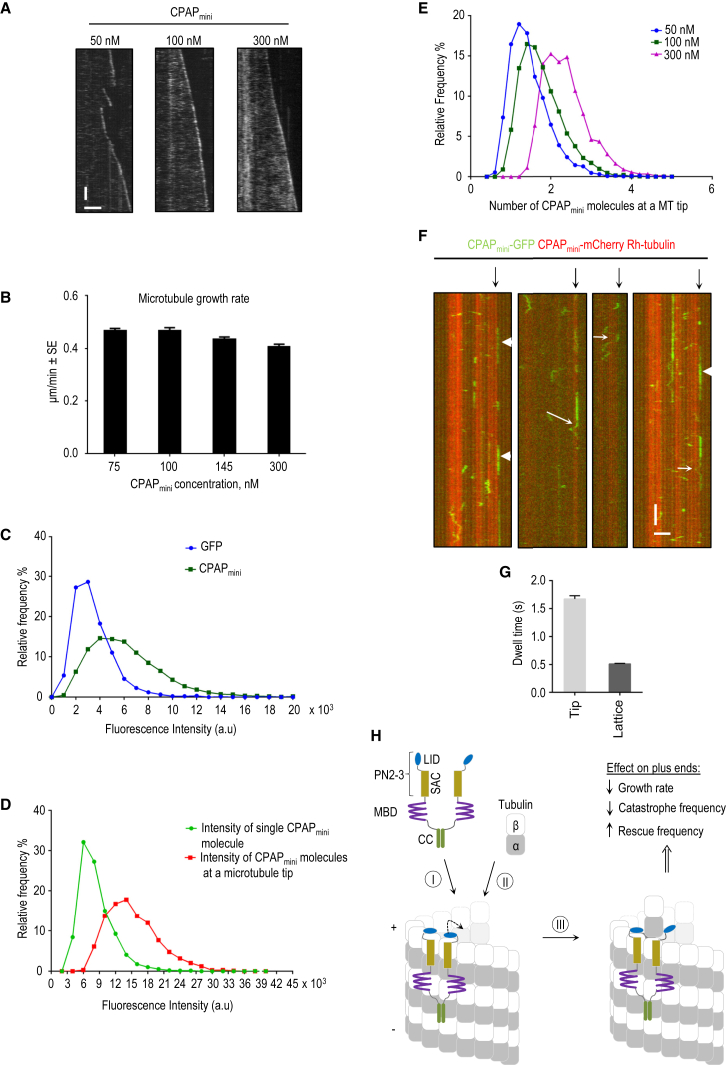

Figure 4.

Counting of CPAPmini Molecules at Microtubule Plus Ends

(A) Kymographs illustrating growth dynamics of microtubule plus ends in the presence of 20 nM mCherry-EB3 and indicated concentrations of CPAPmini. Only the CPAPmini channel is shown. Scale bars represent 2 μm (horizontal) and 60 s (vertical).

(B) Microtubule growth rates at indicated concentrations of CPAPmini in the presence of 20 nM mCherry-EB3. Error bars represent SEM.

(C) Distribution of fluorescence intensities for single molecules of GFP (blue, mean intensity value 3.4 × 103 ± 1.6 × 103) and CPAPmini (green, mean intensity value 6.2 × 103 ± 3.1 × 103). Mean intensity values are reported as means ± SD.

(D) Distribution of fluorescence intensity values for single immobilized CPAPmini molecules (green, mean intensity value = 8.3 × 103 ± 3.2 × 103) compared to CPAPmini (100 nM) molecules at microtubule tips (red, mean intensity value 15.2 × 103 ± 4.7 × 103). Mean intensity values are reported as means ± SD.

(E) Distributions of the numbers of CPAPmini molecules on microtubule plus ends at indicated protein concentrations of CPAPmini. At 100 nM, a concentration sufficient to strongly suppress microtubule growth, ∼2 CPAPmini dimers were bound to microtubule tips (green curve).

(F) Kymographs of dynamic microtubules grown in the presence of 100 nM CPAPmini-mCherry, 5 nM CPAPmini-GFP, and rhodamine-tubulin, demonstrating CPAPmini single-molecule behavior at the tip and lattice. Plus ends are indicated by black arrows. White arrows point to examples showing both lattice diffusion and tip tracking, while molecules displaying stationary behavior at the microtubule tips are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bars represent 2 μm (horizontal) and 2 s (vertical).

(G) Mean dwell times for CPAPmini on the microtubule lattice (mean time = 0.51 ± 0.01, n = 258) and tip (mean time = 1.67 ± 0.06, n = 755) obtained from the dwell-time distributions; reported means were corrected for photobleaching. Error bars represent the error of fit (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

(H) Working model of how CPAPmini ensures slow processive microtubule growth. CPAP recognizes the microtubule plus end via tandemly arranged LID, SAC, and MBD domains (I). This stabilizes the interaction of the terminal tubulin dimers, “caps” the corresponding protofilaments, and stabilizes the microtubule lattice. “Opening” of LID (dashed curved arrow), spontaneously and/or induced by an incoming tubulin dimer (II), enables processive microtubule tip elongation (III).

We next set out to determine the number of CPAPmini molecules at microtubule plus ends. Single-molecule fluorescence intensity analysis of CPAPmini in comparison with GFP confirmed that CPAPmini is a dimer (Figure 4C). To determine the number of CPAPmini molecules at one microtubule tip, we immobilized single CPAPmini molecules on the surface of one flow chamber and performed the in vitro reconstitution assay in the adjacent chamber on the same coverslip. Images of unbleached CPAPmini single molecules were acquired first, after which time-lapse imaging of the in vitro assay with CPAPmini was performed using the same illumination and imaging conditions. We found that approximately two dimers of CPAPmini were present at microtubule tips in the presence of 100 or 300 nM protein, respectively (Figures 4D and 4E). Our tubulin-PN2-3 structural model suggests that CPAPmini, which contains two PN2-3 moieties, interacts with microtubule plus ends by binding to terminal β-tubulin subunits (Figure 2D). Our reconstitution data thus indicate that CPAPmini can reach its full activity with respect to microtubule growth inhibition and catastrophe suppression by binding to approximately four protofilaments.

To acquire mechanistic insights into CPAPmini association with the microtubule tip and lattice, we mixed 5 nM CPAPmini-GFP (Figure 4F) with 100 nM CPAPmini-mCherry. This approach allowed us to observe the behavior of single CPAPmini-GFP molecules in conditions whereby the protein inhibits microtubule growth. Rapid imaging of such samples showed that in most cases CPAPmini directly associated with the microtubule plus end, where it remained stationary and then detached. Occasionally, we observed CPAPmini molecules diffusing toward or away from the microtubule tip (Figure 4F). The analysis of binding events of CPAPmini at growing microtubule plus ends yielded an exponential dwell-time distribution with a mean value of ∼1.7 s (corrected for photobleaching [Helenius et al., 2006]) (Figures 4G, S3A, and S3B). The dwell time for CPAPmini was longer than those observed previously for EB1, EB3, and CLIP-170 in similar conditions (values ranged between ∼0.05 and 0.3 s [Bieling et al., 2008, Montenegro Gouveia et al., 2010]). We also observed binding and unbinding of CPAPmini to the microtubule lattice, with an average dwell time of ∼0.5 s (Figures 4G, S3A, and S3B). On the lattice, both stationary and mobile CPAPmini molecules were detected. We noted that a single CPAPmini molecule could switch between the two types of behavior (Figure 4F). Automated single-particle tracking combined with mean squared displacement (MSD) analysis indicated that the mobile CPAPmini molecule population undergoes one-dimensional diffusion, as the increase of the MSD value over time was linear (Figures S3C–S3E) (Qian et al., 1991). The diffusion coefficient of CPAPmini bound to microtubule lattices was 0.03 ± 0.0004 μm2 s−1 (Table S3). This value is three times lower than that for EB3 and similar to the one for the kinesin-13 MCAK, obtained under similar conditions (Montenegro Gouveia et al., 2010).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that CPAPmini localizes to microtubule plus ends mostly through direct binding and remains largely immobile at the microtubule tip until detachment. This behavior, as well as the longer dwell times at the microtubule plus end compared with the lattice, can be explained by the presence of the LID domain, which can attach CPAPmini to the tip of a protofilament. Our data further show that CPAPmini can either diffuse along the lattice or bind to it in a stationary manner. We think that these two types of CPAPmini behavior might be due to the presence of the MBD and SAC domains, which can independently interact with microtubule lattices. Finally, our results demonstrate that CPAPmini suppresses microtubule growth and stabilizes microtubules by inhibiting catastrophes and promoting rescues. In combination with the structural and biophysical data, our reconstitution data suggest that CPAPmini ensures slow processive microtubule growth by capping and stabilizing the plus ends of protofilaments (Figure 4H).

Both the SAC and MBD Domains of CPAP Are Essential for Centriole Assembly

Our in vitro observations raised the possibility that CPAP could contribute to centriole formation in two ways: the MBD could promote centriolar microtubule assembly by stabilizing microtubules, while LID, together with SAC, might limit centriolar microtubule elongation by slowing growth of their plus ends. To test these predictions in the cellular context, we generated cell lines conditionally expressing YFP-tagged CPAP transgenes resistant to RNAi targeting endogenous CPAP (Kitagawa et al., 2011). We analyzed mitotic cells using the centriolar marker Centrin 2 as a readout of successful centriole assembly. Whereas >90% of control cells contained ≥4 centrioles, this was the case for fewer than 10% of cells depleted of endogenous CPAP (Figures 5A, 5B, 5I, and S4A) (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009). YFP-CPAP rescued this phenotype to a large extent, with >80% of cells having successfully duplicated their centrioles (Figures 5C, 5I, and S4A) (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009). Strikingly, we found that the removal of MBD (ΔMBD) completely abolished centriole assembly, to levels that are even lower than depletion of CPAP alone, likely due to dominant-negative effects following heterodimerization of YFP-CPAP-ΔMBD with any residual endogenous CPAP (Figures 5D, 5I, and S4A). We conclude that the microtubule-stabilizing effect of MBD observed in vitro is essential for centriole biogenesis.

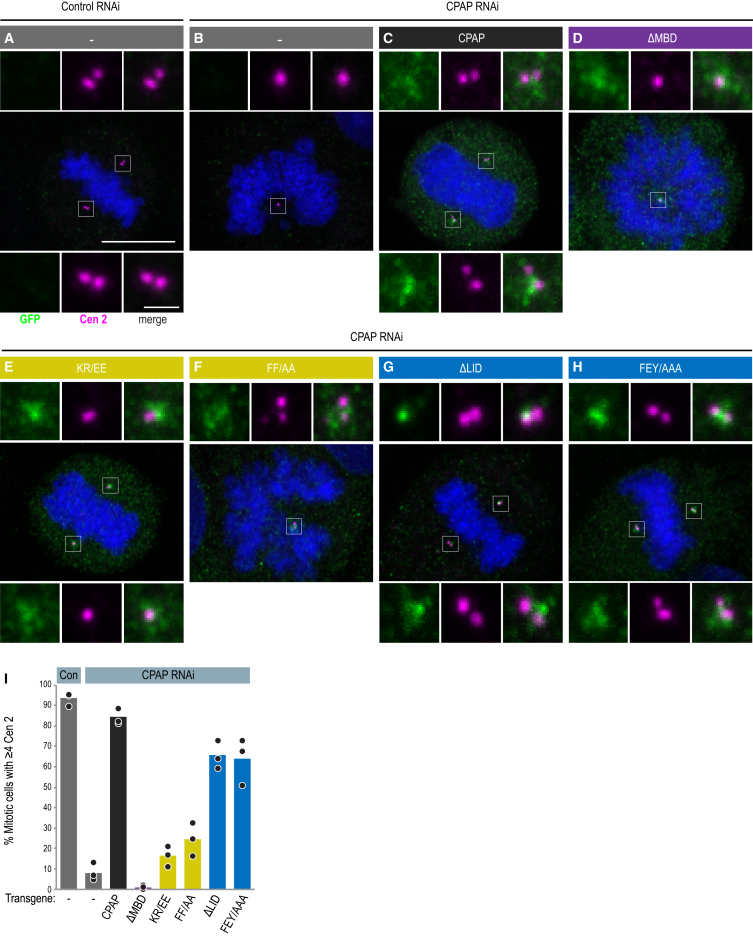

Figure 5.

Effect of PN2-3 Mutations on CPAP Cellular Function

(A–H) Mitotic U2OS FlpIn TREX cell lines without transgene (A and B) or expressing the indicated YFP-CPAP variants (C–H), treated with control siRNA (A) or siRNA targeting endogenous CPAP (B–H), stained with antibodies against Centrin 2 (magenta) and GFP (green); DNA in blue. Scale bars in (A) apply to all images and represent 10 μm in main image and 1 μm in insets.

(I) Percentage of cells showing successful centriole duplication (≥4 Centrin 2 foci). Bars show the mean of three experimental repeats; circles indicate the individual values for each experiment. n > 100 cells analyzed for each condition and per experiment. Two-tailed unequal variance t-tests were used to compare each CPAP mutant to the wild type transgene, with the p values < 0.05 for all samples except FEY/AAA (p = 0.0784). Full dataset is shown in Figure S4A.

We found also that CPAP constructs lacking the LID domain or with key residues mutated, YFP-CPAP-ΔLID and FEY/AAA, respectively, were able to sustain centriole assembly in ∼65% of cells (Figures 5G–5I), indicating that LID contributes to, but is not essential for, this process. In contrast, CPAP function was severely compromised upon mutation of SAC (KR/EE or FF/AA; Figures 5E, 5F, and 5I), in line with previous findings (Hsu et al., 2008, Kitagawa et al., 2011, Tang et al., 2009). Impaired function of all CPAP mutants likely reflects an impact on protein activity, because localization and turnover at the centrosome were unaffected (Figures 5C–5H and S4B). Overall, these results establish that MBD and SAC are critical for centriole assembly, whereas LID appears to play an accessory role in this process.

CPAP Regulates the Length of Centriolar Microtubules in Cells

We further investigated the function of SAC and LID by analyzing cells depleted of endogenous CPAP and overexpressing YFP-CPAP variants, which provided us with an assay system to address the contribution of distinct domains of CPAP to centriole biogenesis. In these conditions, wild-type YFP-CPAP leads to the formation of overly long centrioles that contain not only CPAP but also other centriolar markers such as Centrin 2 along their entire length (Figures 6A and 6D), as reported for cells overexpressing wild-type CPAP in addition to having the endogenous protein (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009). In contrast, we found no overly long centrioles upon YFP-CPAP-ΔMBD overexpression (Figures S4C and S4D), as anticipated from the fact that MBD is essential for centriole assembly. Mutation of SAC (KR/EE or FF/AA) led to a reduction in the proportion of cells with overly long centrioles while deletion of LID had no such effect, again reflecting the respective impact of these variants on the ability of CPAP to sustain regular centriole assembly (Figures 6A, 6D, S4C, and S4D).

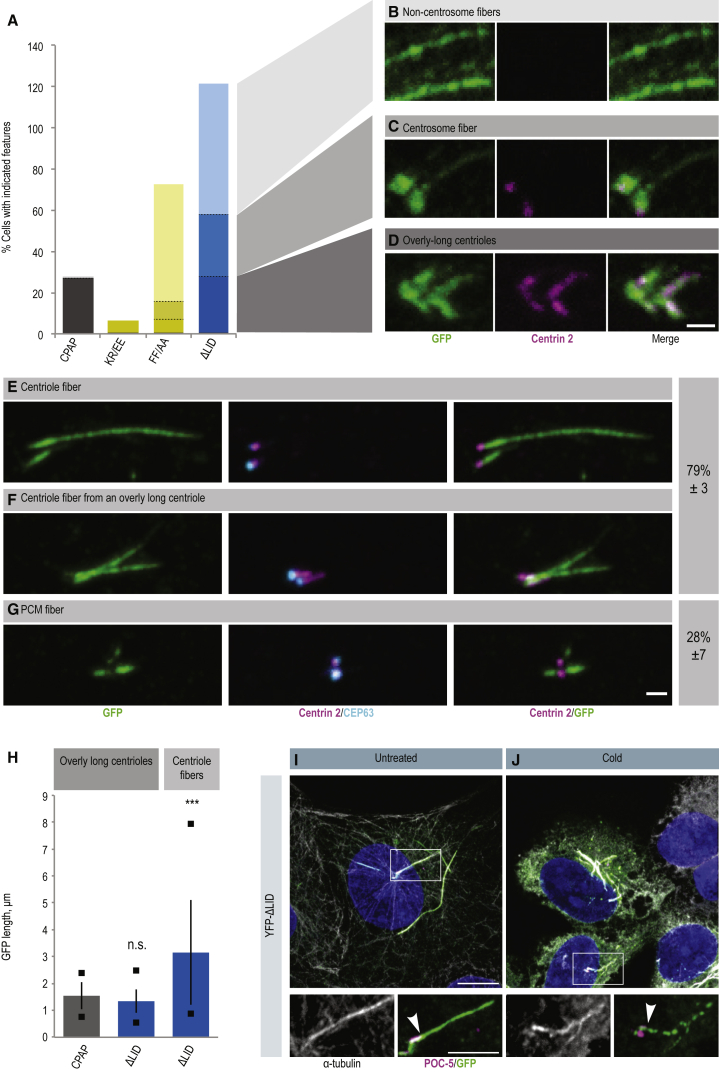

Figure 6.

Fibers Extend from Centrioles upon Expression of CPAP Lacking the LID Domain

(A–D) U2OS cells expressing indicated YFP-CPAP variants and depleted of endogenous CPAP by RNAi, stained with antibodies against Centrin 2 (magenta) and GFP (green). (A) Quantification of the YFP structures illustrated in (B–D) (n > 100 per sample). Note that the total exceeds 100% here and in (E–G) because some cells contain multiple types of structure. Scale bar, 1 μm.

(E–G) Proportion of YFP-CPAP-ΔLID expressing cells with centriole fibers (E and F) or PCM fibers (G). Percentages are the mean of three experiments ± SD; n = 9, 17, and 26 cells, respectively. Scale bar, 1 μm.

(H) Length of overly long centrioles and of centriole fibers in the indicated conditions determined using GFP immunofluorescence. n = 42, 22, and 37 cells, respectively. Bars indicate the mean, squares indicate the minimum and maximum values, and error bars indicate the SD. Student's two-sample two-tailed unequal variance t test comparing ΔLID overly long centrioles and centriole fibers with CPAP-induced overly long centrioles: ∗∗∗p < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

(I and J) YFP-CPAP-ΔLID cells without (I) or with (J) 1 hr incubation on ice stained with antibodies against α-tubulin (gray), GFP (green), and the distal centriole protein POC5 (magenta). Arrowheads indicate end of centrioles from which emanate fibers, as determined by the POC5 signal. Note that the signal of YFP-CPAP-ΔLID along the centriole fiber becomes sparser following ice-induced microtubule depolymerization. Scale bars represent 10 μm (main image) and 5 μm (inset).

Intriguingly, close examination of cells depleted of endogenous CPAP and overexpressing either YFP-CPAP-FF/AA or YFP-CPAP-ΔLID revealed the presence of extended YFP-positive fibers that stemmed from centrosomes, but which did not contain centriolar markers along their length (Figures 6A and 6C). To determine whether such centrosomal fibers originated from centrioles or from the pericentriolar matrix, we conducted immunofluorescence experiments with a marker surrounding the proximal end of parental centrioles (CEP63) and one marking the distal end of all centrioles (Centrin 2). This analysis revealed that ∼80% of centrosomal fibers appeared to be continuations of the distal end of regular centrioles or of overly long centrioles, and were thus termed centriole fibers (Figures 6E and 6F). These fibers, lacking Centrin, were often considerably longer than overly long centrioles bearing Centrin (Figure 6H) and were positive for α-tubulin (Figures 6I and 6J), raising the possibility that they correspond to abnormal extensions of centriolar microtubules.

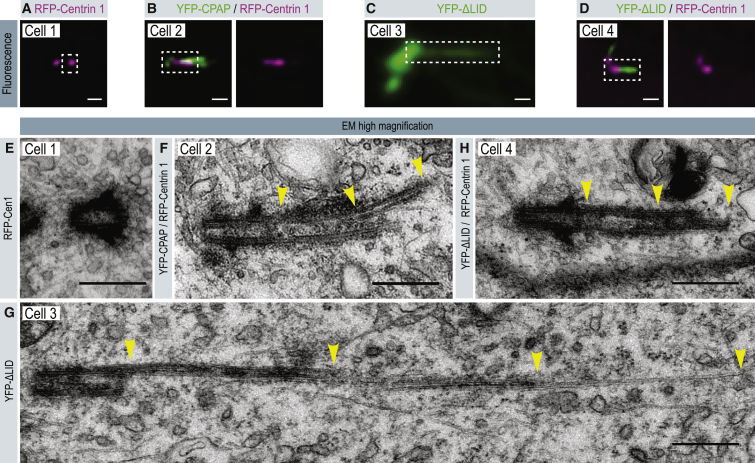

To test this hypothesis, we carried out correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM; Figures 7 and S5). In line with previous observations (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009), we found that cells overexpressing YFP-CPAP and depleted of endogenous CPAP harbored overly long centrioles, in which microtubules extended from the distal end of the centriole (Figures 7B and 7F; compare with 7A and 7E). Strikingly, cells expressing YFP-CPAP-ΔLID also exhibited microtubule extensions from the distal end of the centriole, which attained several microns in some cases (Figures 7C and 7G). To ensure that such figures represented centriole fibers (i.e., devoid of Centrin) and not overly long centrioles (i.e., bearing Centrin), we carried out further CLEM experiments using tagRFP-Centrin 1 as an additional marker. In agreement with our immunofluorescence analysis, we found that YFP-CPAP-ΔLID centriole fibers were indeed microtubules extending from the distal end of centrioles (Figures 7D and 7H). We conclude that the activities of LID and SAC can prevent aberrant overextension of centriolar microtubules.

Figure 7.

Centriole Fibers Are Centriolar Microtubule Extensions

(A–H) CLEM of cells expressing tagRFP-Centrin 1 (Cell 1; A, E), YFP-CPAP and tagRFP-Centrin 1 (Cell 2; B, F), YFP-ΔLID (Cell 3; C, G), or YFP-ΔLID plus tagRFP-Centrin-1 (Cell 4; D, H), and simultaneously depleted of endogenous CPAP using RNAi (Cells 2–4). (A–D) Fluorescence microscopy images of the region of interest in each cell. Scale bar, 1 μm. (E–H) Corresponding high-magnification electron micrographs of the boxed region in (A–D), showing one 50 nm section from a serial section series. Yellow arrowheads indicate microtubule extensions from the distal ends of centrioles. Scale bars, 500 nm. Ten cells expressing YFP-ΔLID were analyzed, which contained a total of 28 centrioles. Of these, three were centrioles with an apparent normal length and structure, two were overly long centrioles without further microtubule extensions, four exhibited PCM fibers, whereas 19 harbored microtubule extensions from their distal ends (as illustrated in G and H). Of these 19 centrioles, six came from the experiment where cells were also expressing tagRFP-Centrin 1 and could therefore be unambiguously classified as centriole fibers (i.e., without tagRFP-Centrin 1 signal) rather than overly long centrioles.

See also Figures S5 and S6.

Discussion

Our study provides fundamental insights into the mechanisms by which the evolutionarily conserved family of CPAP/SAS-4 proteins regulate the growth of centriolar microtubules, thus contributing to setting organelle size. Whereas the crystal structure of the G box of CPAP, either alone or in complex with a peptide derived from the centriolar protein STIL, has been solved (Zheng et al., 2014, Cottee et al., 2013, Hatzopoulos et al., 2013), high-resolution structural information on the evolutionarily conserved domains interacting with tubulin and microtubules was lacking, precluding full understanding of how CPAP regulates centriole biogenesis. The structural and biophysical data presented here reveal a dual binding mode between tubulin and the LID plus SAC domains of PN2-3, explaining its tubulin-sequestering and microtubule-destabilizing activities (Hsu et al., 2008, Cormier et al., 2009, Hung et al., 2004). The finding that LID binds at the tip of β-tubulin, in combination with the structural model suggesting that PN2-3 can bind the terminal β-tubulin subunits on the outside of a microtubule, strongly suggested that PN2-3 represents an autonomous microtubule plus-end targeting domain in CPAP.

To test whether this is the case, we performed dynamic microtubule reconstitution experiments and indeed found that the sequential arrangement of LID, SAC, and MBD in a dimeric configuration localizes CPAPmini to growing microtubule plus ends. The plus-end localization of CPAPmini is unlikely to depend on co-polymerization with tubulin, because tip localization is observed at CPAPmini concentrations that are several orders of magnitude lower than that of tubulin. Analysis of the behavior of single CPAPmini molecules in our in vitro reconstitution system showed that the majority of CPAPmini molecules bound to microtubule plus ends directly. CPAPmini also displayed one-dimensional diffusion along the microtubule lattice, as described previously for other microtubule-end-interacting proteins (Brouhard et al., 2008, Bieling et al., 2008, Helenius et al., 2006, Montenegro Gouveia et al., 2010); however, diffusion did not seem to be a major contributing factor responsible for the recruitment of CPAPmini to microtubule plus ends. Notably, in the context of a centriole, CPAP is expected to be organized in a precise manner along the inside of the centriole wall where it binds STIL, and is thus very likely not diffusive (Hatzopoulos et al., 2013).

Our reconstitution data revealed that depending on the conditions, microtubule-tip-localized CPAPmini slows down microtubule growth 5- to 8-fold and that only a few CPAPmini molecules suffice to induce this effect. Based on the structural and biophysical results, we propose that the LID and SAC domains of CPAPmini bind terminal β-tubulin subunits exposed at the microtubule plus ends and thereby occlude the binding sites for the incoming tubulin dimers. The ability of PN2-3 to block longitudinal tubulin-tubulin interactions is reminiscent of the tubulin-sequestering protein stathmin and the microtubule plus-end capping ligands DARPin D1, eribulin, and maytansine (Gigant et al., 2000, Pecqueur et al., 2012, Smith et al., 2010, Prota et al., 2014). However, in striking contrast to these microtubule-destabilizing and polymerization-blocking agents, CPAPmini stabilizes microtubules by potently suppressing catastrophes and promoting rescues. The latter property can be attributed to the MBD, which binds strongly to the microtubule lattice and can autonomously induce rescues. The MBD is positively charged, and its binding to negatively charged microtubules likely involves an electrostatic mechanism, similar to that of microtubule lattice-binding regions of cytoplasmic microtubule regulators such as XMAP215/ch-TOG (Brouhard et al., 2008, Widlund et al., 2011). We assume that the MBD of CPAPmini binds along, as well as between, protofilaments to stabilize microtubules.

Based on these considerations, we conclude that this particular mode of binding to microtubule plus ends, due to the combination of LID, SAC, and MBD, can “cap” and stabilize terminal tubulin dimers (Figure 4H). We postulate that in this state, a capped protofilament can only be elongated by an incoming tubulin dimer if the LID domain is released and frees the interaction site needed for establishing longitudinal tubulin-tubulin contacts. The release of LID in turn weakens the CPAPmini microtubule plus-end interaction and either promotes CPAPmini detachment or enables the liberated PN2-3 domain to cap the newly elongated protofilament or a neighboring one. Notably, slowing microtubule growth normally promotes catastrophes by reducing the size of the GTP cap (Walker et al., 1988, Janson et al., 2003). Accordingly, microtubule polymerization suppressors typically act as microtubule depolymerases. However, exceptions to this rule are known, including the kinesin-4 family members Xklp1/KIF4 and KIF21A which, similarly to CPAPmini, can suppress both microtubule growth and catastrophes (Bringmann et al., 2004, Bieling et al., 2010, Van der Vaart et al., 2013). The molecular basis of kinesin-4-mediated microtubule growth inhibition is not understood, but is very likely distinct from that of CPAPmini, because both Xklp1/KIF4 and KIF21A are molecular motors that can move along microtubules and accumulate at microtubule plus ends due to their processive motility (Bieling et al., 2010, Van der Vaart et al., 2013). In contrast, CPAP presents a unique arrangement of tubulin-binding and microtubule-lattice-binding domains, which together have the potential to recognize, cap, and stabilize microtubule plus ends, a mechanism that to our knowledge has not been previously described for any microtubule regulator.

In cells, centriolar microtubules grow very slowly and processively as judged from the analysis of specimens prepared from different stages of the cell cycle (Kuriyama and Borisy, 1981, Chretien et al., 1997). However, the mechanisms underlying such slow and regulated elongation have remained elusive. Our study reveals that CPAP plays a critical dual role in ensuring that this is the case. First, our data indicate that a pivotal function of CPAP is to stabilize centriolar microtubules via its MBD, which likely explains why this domain is essential for centriole assembly. Second, although the capacity of LID to cap microtubule plus ends is not essential for this stabilization function, and thus for centriole formation, it exerts a negative role by limiting microtubule extension from the distal end of centrioles. The SAC domain, which interacts with the lateral side of tubulin dimers, can contribute to both microtubule stabilization and capping functions, potentially explaining why mutations in SAC affect centriole formation more strongly than those in LID. These considerations can at least partially explain why centrioles overelongate when CPAP dosage is increased (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009); however, additional mechanisms likely control the activity of CPAP domains in cells. Our in vitro data revealed that approximately two CPAPmini dimers are sufficient to limit the growth rate of a single microtubule, suggesting that CPAP works at substoichiometric levels. In the context of the centriolar microtubule wall, we expect approximately two CPAP dimers to be able to access the microtubule tips of each triplet from the luminal side of the centriole (Figure S6) (Hatzopoulos et al., 2013, Sonnen et al., 2012, Tang et al., 2011).

Overall, our results reveal that CPAP is a highly specialized microtubule plus-end regulator that acts as a molecular cap to ensure slow and processive growth of centriolar microtubules. Given that endogenous CPAP is present primarily in the proximal region of mature centrioles (Kohlmaier et al., 2009, Schmidt et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2009), we propose that CPAP activity is most critical during the early stages of centriole elongation. Upon overexpression of the wild-type protein, excess CPAP molecules localize along the entire length of centrioles and could cause overelongation of centriolar microtubules due to the microtubule stabilization activity of ectopic CPAP. Furthermore, we speculate that upon overexpression of a mutant protein lacking LID-domain function, overelongation of centriolar microtubules is exacerbated due to the lack of capping function (Figure S6).

We note that microtubule growth rates obtained in vitro upon CPAPmini addition are still some three orders of magnitude faster than those estimated for centriolar microtubules in cells (Kuriyama and Borisy, 1981, Chretien et al., 1997). Regions of CPAP outside of the microtubule- and tubulin-binding domains, including the G box, that may organize CPAP molecules along the entire length of the microtubule wall in a precise manner (Hatzopoulos et al., 2013), as well as post-translational modifications, could be important to further bolster CPAP activity; these features are not recapitulated by the CPAPmini and CPAPlong constructs used in our study. In addition, other centriolar proteins have been implicated in controlling centriole length, including the CPAP-interacting proteins CEP120, CEP135, and Centrobin (Gudi et al., 2011, Lin et al., 2013a, Lin et al., 2013b). It will be of prime interest to assess on a mechanistic level how these proteins cooperate to impact on CPAP function or otherwise contribute to regulate organelle size.

Experimental Procedures

Protein/Peptide Preparation and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Standard protein production in bacteria and peptide synthesis is described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. ITC experiments were performed at 25°C using an ITC200 system (Microcal). Proteins were buffer-exchanged to BRB80 (80 mM PIPES-KOH [pH 6.8] supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM EGTA) supplemented with 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine. 0.1–0.4 mM PN2-3 variants in the syringe were injected stepwise into 10–20 μM tubulin solutions in the cell. The resulting heats were integrated and fitted in Origin (OriginLab) using the standard “one set of sites” model provided by the software package.

Structure Determination

Structure solution by X-ray crystallography is described in full in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. In brief, equimolar amounts of D1, PN2-3, and subtilisin-treated tubulin were mixed and the PN2-3-tubulin-D1 complex was concentrated to ∼20 mg/ml. PN2-3-tubulin-D1 samples were complemented with 0.2 mM GDP, 1 mM colchicine, and 5 mM DTT before setting up sitting-drop vapor diffusion crystallization trials. Crystals were obtained in a condition containing 20% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 550 monomethyl ether and 0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (pH 6.5). X-Ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K at beamline X06DA at the Swiss Light Source. The PN2-3-tubulin-D1 structure was solved by molecular replacement using the αβ-tubulin-D1 complex structure as a search model (PDB: 4DRX). Data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table S2.

In Vitro Reconstitution Assays

Protein purification for in vitro reconstitution assays is described in full in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Reconstitution of microtubule growth dynamics in vitro was performed as described previously (Montenegro Gouveia et al., 2010). In brief, flow chambers were functionalized by sequential incubation with 0.2 mg/ml PLL-PEG-biotin (Susos) and 1 mg/ml NeutrAvidin (Invitrogen) in MRB80 buffer (80 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) [pH 6.8] supplemented with 4 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM EGTA). GMPCPP-microtubule seeds were attached to coverslips through biotin-NeutrAvidin interactions. The reaction mix with or without CPAPmini proteins (MRB80 buffer supplemented with 15 μM tubulin, 0.5 μM rhodamine-tubulin, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM guanosine triphosphate, 0.2 mg/ml κ-casein, 0.1% methylcellulose, and oxygen scavenger mix [50 mM glucose, 400 μg/ml glucose oxidase, 200 μg/ml catalase, and 4 mM DTT]) was added to the flow chamber. Flow chambers were sealed and dynamic microtubules were imaged immediately at 30°C using TIRF microscopy. Intensity analysis for CPAPmini along microtubules, single-molecule fluorescence intensity analysis of CPAPmini, CPAPmini molecule counting at microtubule tips, analysis of microtubule plus-end dynamics, and statistical analysis procedures are all described in full in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Immunofluorescence, Antibodies, and Microscopy

Cells were grown on glass coverslips and fixed in methanol for 7 min at −20°C. Cold treatment was carried out by incubating cells in ice-cold PBS, on ice, for 1 hr before fixation. Cells were permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100, washed in PBS and 0.01% Triton X-100, and blocked for 1 hr in PBS, 1% BSA, and 2% fetal calf serum. All antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution and incubated for either 1 hr at room temperature or ∼12 hr at 4°C. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-α-tubulin (DM1a, Sigma), mouse “20H5” anti-centrin-2 (a gift from J. Salisbury), rabbit anti-hPOC5 (Azimzadeh et al., 2009; a gift from M. Bornens), rabbit anti-CEP63 (Millipore 06-1292), goat anti-GFP (Abcam ab6673), and rabbit anti-GFP (a gift from V. Simanis). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568, donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488, donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568, and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen). All primary antibodies were diluted 1,000-fold, except Centrin 2 (2000×) and anti-α-tubulin (5000×). All secondary antibodies were diluted 1,000-fold. Samples were washed three times between, and after, antibody incubations and incubated with 1 μg/ml Hoechst in PBS prior to mounting in PBS, 90% glycerol, and 4% N-propyl gallate.

Confocal imaging was carried out using a Zeiss LSM 700 microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63× oil-immersion objective, NA 1.40. Z sections were imaged at an interval of ∼0.2 μm. All images shown are maximum-intensity projections and were processed using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012), maintaining relative intensities within a series.

Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy

CLEM is described in full in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. In brief, endogenous CPAP was depleted by RNAi for 72 hr, simultaneous with induction of the transgene. For dual marker experiments, cells were transfected with a tagRFP-Centrin 1 expression vector 16 hr prior to fixation. Cells were fixed, then washed thoroughly with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), and imaged by light microscopy. Immediately afterward, samples were post-fixed for 40 min in 1.0% osmium tetroxide, then 30 min in 1.0% uranyl acetate in water, before being dehydrated through increasing concentrations of alcohol and then embedded in Durcupan ACM resin (Fluka). The coverslips were then placed face down on a glass slide coated with mold-releasing agent (Glorex), with approximately 1 mm of resin separating the two. These regions were mounted on blank resin blocks with acrylic glue and trimmed with glass knives to form a block ready for serial sectioning. Series of between 150 and 300 thin sections (50 nm thickness) were cut with a diamond knife mounted on an ultramicrotome (Leica UC7). These sections were contrasted with lead citrate and uranyl acetate and images taken using an FEI Spirit transmission electron microscope equipped with an Eagle CCD camera.

Author Contributions

A.S., A. Aher, N.J.D., E.A.K., M.C., R.A.K., A. Akhmanova, P.G., and M.O.S. designed the experiments. A.S., A. Aher, N.J.D., D.F., E.A.K., R.J., I.G., and M.C. conducted the experiments. A.S., A. Aher, N.J.D., A. Akhmanova, P.G., and M.O.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

Acknowledgments

X-ray data were collected at beamline X06DA of the Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland). Eribulin was a kind gift from Eisai Co. We are grateful to Graham Knott, head of the Bio-EM Facility in the School of Life Sciences at EPFL, for help in setting up CLEM, and to Christian Arquint and Erich Nigg (Basel, Switzerland) for their gift of the U2OS FlpIn TREX cell line. We thank Marileen Dogterom, Virginie Hachet, and John Vakonakis for useful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by an EMBO Long Term Fellowship (to A.S.), as well as by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030B_138659 and 31003A_166608 to M.O.S.) and the European Research Council (AdG 340227 to P.G. and Synergy grant 609822 to A.A.).

Published: May 23, 2016

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, six figures, and three tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2016.04.024.

Contributor Information

Anna Akhmanova, Email: a.akhmanova@uu.nl.

Pierre Gönczy, Email: pierre.gonczy@epfl.ch.

Michel O. Steinmetz, Email: michel.steinmetz@psi.ch.

Accession Numbers

Coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under accession number PDB: 5ITZ (D1-tubulin-PN2-3).

Supplemental Information

References

- Alday P.H., Correia J.J. Macromolecular interaction of halichondrin B analogues eribulin (E7389) and ER-076349 with tubulin by analytical ultracentrifugation. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7927–7938. doi: 10.1021/bi900776u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimzadeh J., Marshall W.F. Building the centriole. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:R816–R825. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimzadeh J., Hergert P., Delouvee A., Euteneuer U., Formstecher E., Khodjakov A., Bornens M. hPOC5 is a centrin-binding protein required for assembly of full-length centrioles. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:101–114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling P., Laan L., Schek H., Munteanu E.L., Sandblad L., Dogterom M., Brunner D., Surrey T. Reconstitution of a microtubule plus-end tracking system in vitro. Nature. 2007;450:1100–1105. doi: 10.1038/nature06386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling P., Kandels-Lewis S., Telley I.A., van D.J., Janke C., Surrey T. CLIP-170 tracks growing microtubule ends by dynamically recognizing composite EB1/tubulin-binding sites. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:1223–1233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling P., Telley I.A., Surrey T. A minimal midzone protein module controls formation and length of antiparallel microtubule overlaps. Cell. 2010;142:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J., Roberts E., Springell K., Lizarraga S.B., Scott S., Higgins J., Hampshire D.J., Morrison E.E., Leal G.F., Silva E.O. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:353–355. doi: 10.1038/ng1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornens M. The centrosome in cells and organisms. Science. 2012;335:422–426. doi: 10.1126/science.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann H., Skiniotis G., Spilker A., Kandels-Lewis S., Vernos I., Surrey T. A kinesin-like motor inhibits microtubule dynamic instability. Science. 2004;303:1519–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1094838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouhard G.J., Stear J.H., Noetzel T.L., Al-Bassam J., Kinoshita K., Harrison S.C., Howard J., Hyman A.A. XMAP215 is a processive microtubule polymerase. Cell. 2008;132:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chretien D., Buendia B., Fuller S.D., Karsenti E. Reconstruction of the centrosome cycle from cryoelectron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 1997;120:117–133. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier A., Clement M.J., Knossow M., Lachkar S., Savarin P., Toma F., Sobel A., Gigant B., Curmi P.A. The PN2-3 domain of centrosomal P4.1-associated protein implements a novel mechanism for tubulin sequestration. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6909–6917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808249200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottee M.A., Muschalik N., Wong Y.L., Johnson C.M., Johnson S., Andreeva A., Oegema K., Lea S.M., Raff J.W., van B.M. Crystal structures of the CPAP/STIL complex reveal its role in centriole assembly and human microcephaly. Elife. 2013;2:e01071. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigant B., Curmi P.A., Martin-Barbey C., Charbaut E., Lachkar S., Lebeau L., Siavoshian S., Sobel A., Knossow M. The 4 A X-ray structure of a tubulin:stathmin-like domain complex. Cell. 2000;102:809–816. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigant B., Wang C., Ravelli R.B., Roussi F., Steinmetz M.O., Curmi P.A., Sobel A., Knossow M. Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine. Nature. 2005;435:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature03566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczy P. Towards a molecular architecture of centriole assembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:425–435. doi: 10.1038/nrm3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczy P. Centrosomes and cancer: revisiting a long-standing relationship. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:639–652. doi: 10.1038/nrc3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan J., Chim Y.C., Ha A., Basiri M.L., Lerit D.A., Rusan N.M., Avidor-Reiss T. Tubulin nucleotide status controls Sas-4-dependent pericentriolar material recruitment. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:865–873. doi: 10.1038/ncb2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudi R., Zou C., Li J., Gao Q. Centrobin-tubulin interaction is required for centriole elongation and stability. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:711–725. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzopoulos G.N., Erat M.C., Cutts E., Rogala K.B., Slater L.M., Stansfeld P.J., Vakonakis I. Structural analysis of the G-box domain of the microcephaly protein CPAP suggests a role in centriole architecture. Structure. 2013;21:2069–2077. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius J., Brouhard G., Kalaidzidis Y., Diez S., Howard J. The depolymerizing kinesin MCAK uses lattice diffusion to rapidly target microtubule ends. Nature. 2006;441:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature04736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W.B., Hung L.Y., Tang C.J., Su C.L., Chang Y., Tang T.K. Functional characterization of the microtubule-binding and -destabilizing domains of CPAP and d-SAS-4. Exp. Cell Res. 2008;314:2591–2602. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung L.Y., Chen H.L., Chang C.W., Li B.R., Tang T.K. Identification of a novel microtubule-destabilizing motif in CPAP that binds to tubulin heterodimers and inhibits microtubule assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:2697–2706. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S.C., Marteil G., Bettencourt-Dias M. Mapping molecules to structure: unveiling secrets of centriole and cilia assembly with near-atomic resolution. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;26:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson M.E., de Dood M.E., Dogterom M. Dynamic instability of microtubules is regulated by force. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:1029–1034. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Hua S., Mohan R., Grigoriev I., Yau K.W., Liu Q., Katrukha E.A., Altelaar A.F., Heck A.J., Hoogenraad C.C. Microtubule minus-end stabilization by polymerization-driven CAMSAP deposition. Dev. Cell. 2014;28:295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K., Arnal I., Desai A., Drechsel D.N., Hyman A.A. Reconstitution of physiological microtubule dynamics using purified components. Science. 2001;294:1340–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1064629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham M., Muller-Reichert T., Oegema K., Grill S., Hyman A.A. SAS-4 is a C. elegans centriolar protein that controls centrosome size. Cell. 2003;112:575–587. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa D., Kohlmaier G., Keller D., Strnad P., Balestra F.R., Fluckiger I., Gönczy P. Spindle positioning in human cells relies on proper centriole formation and on the microcephaly proteins CPAP and STIL. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:3884–3893. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmaier G., Loncarek J., Meng X., McEwen B.F., Mogensen M.M., Spektor A., Dynlacht B.D., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama R., Borisy G.G. Centriole cycle in Chinese hamster ovary cells as determined by whole-mount electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 1981;91:814–821. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidel S., Gönczy P. SAS-4 is essential for centrosome duplication in C elegans and is recruited to daughter centrioles once per cell cycle. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:431–439. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.C., Chang C.W., Hsu W.B., Tang C.J., Lin Y.N., Chou E.J., Wu C.T., Tang T.K. Human microcephaly protein CEP135 binds to hSAS-6 and CPAP, and is required for centriole assembly. EMBO J. 2013;32:1141–1154. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.N., Wu C.T., Lin Y.C., Hsu W.B., Tang C.J., Chang C.W., Tang T.K. CEP120 interacts with CPAP and positively regulates centriole elongation. J. Cell Biol. 2013;202:211–219. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro Gouveia S., Leslie K., Kapitein L.C., Buey R.M., Grigoriev I., Wagenbach M., Smal I., Meijering E., Hoogenraad C.C., Wordeman L. In vitro reconstitution of the functional interplay between MCAK and EB3 at microtubule plus ends. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1717–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E.A., Raff J.W. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009;139:663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea E.K., Klemm J.D., Kim P.S., Alber T. X-ray structure of the GCN4 leucine zipper, a two-stranded, parallel coiled coil. Science. 1991;254:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1948029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecqueur L., Duellberg C., Dreier B., Jiang Q., Wang C., Pluckthun A., Surrey T., Gigant B., Knossow M. A designed ankyrin repeat protein selected to bind to tubulin caps the microtubule plus end. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204129109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prota A.E., Bargsten K., Diaz J.F., Marsh M., Cuevas C., Liniger M., Neuhaus C., Andreu J.M., Altmann K.H., Steinmetz M.O. A new tubulin-binding site and pharmacophore for microtubule-destabilizing anticancer drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:13817–13821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408124111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Sheetz M.P., Elson E.L. Single particle tracking. Analysis of diffusion and flow in two-dimensional systems. Biophys. J. 1991;60:910–921. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T.I., Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le C.M., Lavoie S.B., Stierhof Y.D., Nigg E.A. Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.A., Wilson L., Azarenko O., Zhu X., Lewis B.M., Littlefield B.A., Jordan M.A. Eribulin binds at microtubule ends to a single site on tubulin to suppress dynamic instability. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1331–1337. doi: 10.1021/bi901810u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen K.F., Schermelleh L., Leonhardt H., Nigg E.A. 3D-structured illumination microscopy provides novel insight into architecture of human centrosomes. Biol. Open. 2012;1:965–976. doi: 10.1242/bio.20122337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.J., Fu R.H., Wu K.S., Hsu W.B., Tang T.K. CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:825–831. doi: 10.1038/ncb1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.J., Lin S.Y., Hsu W.B., Lin Y.N., Wu C.T., Lin Y.C., Chang C.W., Wu K.S., Tang T.K. The human microcephaly protein STIL interacts with CPAP and is required for procentriole formation. EMBO J. 2011;30:4790–4804. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vaart B., van Riel W.E., Doodhi H., Kevenaar J.T., Katrukha E.A., Gumy L., Bouchet B.P., Grigoriev I., Spangler S.A., Yu K.L. CFEOM1-associated kinesin KIF21A is a cortical microtubule growth inhibitor. Dev. Cell. 2013;27:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R.A., O'Brien E.T., Pryer N.K., Soboeiro M.F., Voter W.A., Erickson H.P., Salmon E.D. Dynamic instability of individual microtubules analyzed by video light microscopy: rate constants and transition frequencies. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widlund P.O., Stear J.H., Pozniakovsky A., Zanic M., Reber S., Brouhard G.J., Hyman A.A., Howard J. XMAP215 polymerase activity is built by combining multiple tubulin-binding TOG domains and a basic lattice-binding region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2741–2746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016498108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Alushin G.M., Brown A., Nogales E. Mechanistic origin of microtubule dynamic instability and its modulation by EB proteins. Cell. 2015;162:849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Jin C., Chu Y., Varghese C., Hua S., Yan F., Miao Y., Liu J., Mann D., Ding X. Dimerization of CPAP orchestrates centrosome cohesion plasticity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:2488–2497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Gooi L.M., Wason A., Gabriel E., Mehrjardi N.Z., Yang Q., Zhang X., Debec A., Basiri M.L., Avidor-Reiss T. Conserved TCP domain of Sas-4/CPAP is essential for pericentriolar material tethering during centrosome biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E354–E363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317535111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.