Abstract

Background/Aims. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). In addition, there may be an association between leukemia and lymphoma and IBD. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the IBD literature to estimate the incidence of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in adult IBD patients. Methods. Studies were identified by a literature search of PubMed, Cochrane Library, Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Pooled incidence rates (per 100,000 person-years [py]) were calculated through use of a random effects model, unless substantial heterogeneity prevented pooling of estimates. Several stratified analyses and metaregression were performed to explore potential study heterogeneity and bias. Results. Thirty-six articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. For CRC, the pooled incidence rate in CD was 53.3/100,000 py (95% CI 46.3–60.3/100,000). The incidence of leukemia was 1.5/100,000 py (95% CI −0.06–3.0/100,000) in IBD, 0.3/100,000 py (95% CI −1.0–1.6/100,000) in CD, and 13.0/100,000 py (95% CI 5.8–20.3/100,000) in UC. For lymphoma, the pooled incidence rate in CD was 0.8/100,000 py (95% CI −0.4–2.1/100,000). Substantial heterogeneity prevented the pooling of other incidence estimates. Conclusion. The incidence of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in IBD is low.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence is higher in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients than in the general population, and CRC accounts for an estimated 10–15% of deaths in patients with IBD [1]. The risk conferred by IBD may be due to chronic inflammation combined with genetic factors [1–3]. Patients with extensive inflammation, a younger age at diagnosis, long disease duration, comorbid primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and pseudopolyposis are at the highest risk [4–14].

IBD patients receiving immunomodulators may or may not also be at higher risk of lymphoproliferative disorders such as lymphoma and leukemia [15–19]. The risk of lymphoma in IBD patients is low but appears to be higher than in the general population [6, 8, 14, 20–22]. The risk of leukemia in IBD is less clear [6, 8, 14, 23, 24].

Understanding the risk of development of these malignancies inherent to IBD is crucial for cancer surveillance strategies. In addition, determination of the absolute increase in risk of these malignancies from IBD pharmacotherapy is a crucial consideration for providers and patients. The aims of this study are to estimate the incidence of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in adult IBD patients through a systematic review and meta-analysis. Unique to this study, we attempt to evaluate the underlying risk of these cancers in IBD overall and separately Crohn's Disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) and exclude the effects of IBD pharmacotherapy (specifically immunomodulators and biologics), given the evidence that these medications may increase cancer risk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

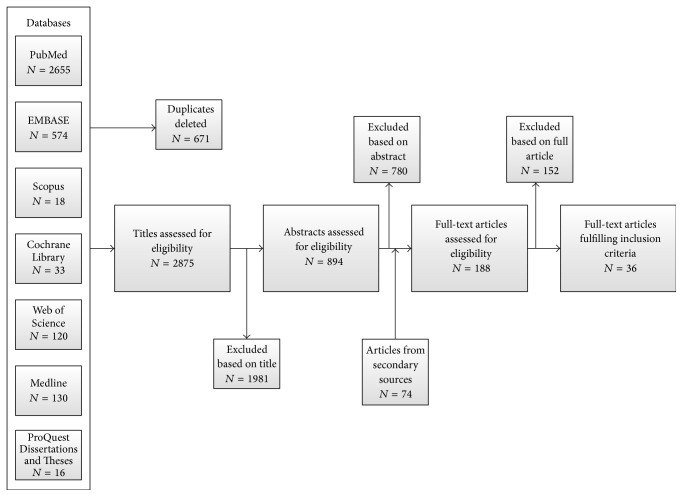

A detailed literature search was conducted to identify all published and unpublished studies examining the incidence of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in adult IBD patients. We searched the PubMed, Cochrane Library, Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses databases. Reference lists of published articles were hand searched for secondary sources and experts in the field contacted for unpublished data. Furthermore, https://clinicaltrials.gov/, the WHO International Clinical Trial Registry, and scientific information packets of approved IBD pharmacotherapies were scrutinized for additional information sources. No restrictions on language, country of origin, or publication date were used. Figure 1 outlines the literature search and Supplementary Table 1 (in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/1632439) details the search strategy employed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting the identification of studies, inclusion, and exclusion assessment.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All studies that reported incidence or provided information sufficient to accurately calculate incidence for the three cancers of interest in adult IBD patients were included. Studies focusing on pediatric populations, not reporting person-years of follow-up, of duration less than one year, and not written in English and unable to be translated to English were excluded. If publications reported duplicate data on a population, only the publication with the longest follow-up period was included.

2.3. Data Collection and Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers (CW and KCS) examined each article for inclusion according to the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus. Thirty-six articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Twenty-five articles reported incidence estimates for CRC [7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24–39], ten for leukemia [8, 14, 18, 19, 21–24, 33, 39], and twenty-one for lymphoma [8, 10, 14, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 26, 33, 34, 39–48] (some articles reported incidence estimates for multiple cancers). Figure 1 outlines the search flowchart.

We retrieved demographic (where possible) and outcome data for each included article using standardized forms. Individual studies were assigned a bias risk rating using the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias Assessment Tool: for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI) [49]. The strength of evidence for each cancer was assessed utilizing the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [50].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Individual study unadjusted incidence rates (per 100,000 person-years [py]) were calculated from the reported number of cancer cases and person-years of follow-up for each outcome separately. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated assuming a Poisson distribution [51]. In situations with zero observed cases, the value of 3.7 was used to calculate incidence rates and the confidence interval upper limit [51].

As our interest is in quantifying the incidence rate of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in IBD patients not treated with immunomodulators or biologic agents (and treatment information is often unreported), two stratification variables were created using study publication year as an estimate of when each medication class became widely used. 1995 was used as the dividing year for widespread immunomodulator use and 2000 for biologic use. Pooled incidence rates with 95% CIs were then calculated for (1) each cancer overall, (2) each cancer in CD and UC separately, (3) each cancer stratified by year of publication, and (4) each cancer stratified by country of origin (to determine if incidence varied by geographic region). A random effects model was used to account for potential between-study variations. The I 2 statistic was used to quantify the percentage of heterogeneity for all pooled estimates from between-study variation, with ≥75% indicating substantial heterogeneity [52]. Publication bias and the presence of other small study effects were measured through visual assessment of funnel plot symmetry and Egger's test [52]. Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Metaregression was used to further test the effects of study- and subject-level covariates on cancer risk, as well as the degree of between-study heterogeneity explained by the covariates through calculation of the adjusted R 2. The adjusted R 2 measures the relative reduction in the between-study variance explained by the covariates in the model and is presented as a percentage [52]. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX). p values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

3.1.1. Colorectal Cancer

Reported incidence rates of CRC in IBD ranged from 41.5/100,000 py (95% CI 24.5–58.5/100,000) to 543.5/100,000 py (95% CI 316.4–770.6/100,000) (Table 1). Substantial heterogeneity prevented pooling of estimates using a random effects model (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 174.65; p < 0.001; I 2 = 86.3%). Therefore, we present unpooled incidence estimates. Separate sensitivity analyses excluding the studies with the highest individual incidence estimate [31] and the study with the greatest weight on the pooled estimate [7] did not significantly change the degree of heterogeneity present.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies of CRC in IBD.

(a).

| Author | Journal | Publication year | Study design | Study population | Region of origin | Number of sites | Study duration (yrs) | Person-years | Number of patients | Diagnosis | Mean age (yrs) | Female (%) | Mean disease duration (yrs) | Surgery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askling et al. [25] | Gastroenterology | 2001 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 54 | 169,332 91,833 77,499 |

19,459 8,810 10,649 |

IBD CD UC |

48.6 53.0 45.0 |

|||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Bernstein et al. [24] | Cancer | 2001 | Case-control | Administrative claims | Canada | Regionwide | 14 | 41,005 21,340 19,665 |

5,529 2,857 2,672 |

IBD CD UC |

39.0 36.3 41.7 |

54.5 59.0 50.0 |

||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Farrell et al. [26] | Gut | 2000 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | 1 | 9 | 6,256 | 782 | IBD∗ | 44.1 | 52.0 | 10.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Fraser et al. [18] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2002 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | Countywide | 35 | 55,388 20,494 34,894 |

1,578 584 994 |

IBD CD UC |

35.0 | 53.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Gillen et al. [27] | Gut | 1994 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 30 | 12,324 2,320 10,004 |

611 125 486 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Herrinton et al. [28] | Gastroenterology | 2012 | Cohort | Administrative claims | United States | Countywide | 12 | 61,793 28,469 33,324 |

14,875 5,053 9,822 |

IBD CD UC |

61.8 62.4 61.1 |

|||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Hou et al. [29] | Inflamm Bowel Dis | 2012 | Cohort | National registry | United States | Countrywide | 11 | 112,243 | 20,949 | UC | 61.6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [7] | Gastroenterology | 2012 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countywide | 29 | 385,608 130,391 255,217 |

47,374 14,463 32,911 |

IBD CD UC |

40.3 35.7 44.9 |

55.0 57.0 53.0 |

||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [39] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2004 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 35 | 6,569 | 374 | CD | 58.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jussila et al. [10] | Scand J Gastroenterol | 2013 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 23 | 232,536 51,876 180,660 |

20,970 4,983 15,987 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lakatos et al. [38] | Inflamm Bowel Dis | 2006 | Cohort | Provincial registry | Europe (Eastern) | 7 | 11 | 8,564 | 723 | UC | 49.0 | 47.0 | 10.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lakatos et al. [30] | J Crohn's Colitis | 2011 | Cohort | Provincial registry | Europe (Eastern) | 7 | 31 | 5,758 | 506 | CD | 31.5 | 50.4 | 31.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lennard-Jones et al. [31] | Gut | 1990 | Cohort | Surveillance | Europe (Western) | 1 | 21 | 4,048 | 401 | UC | 42.6 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lovasz et al. [32] | J Gastroenterol Liver Dis | 2013 | Cohort | Provincial registry | Europe (Eastern) | Regionwide | 34 | 7,759 | 640 | CD | 28.0 | 49.8 | 11.0 | 38.4 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Manninen et al. [11] | J Crohn's Colitis | 2013 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | 1 | 21 | 22,900 7,265 15,635 |

1,804 551 1,253 |

IBD CD UC |

33.0 30.0 34.0 |

47.0 51.0 45.0 |

13.5 13.0 13.1 |

46.0 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mellemkjær et al. [33] | Cancer Causes Control | 2000 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 16 | 22,875 | 2,645 | CD | 50.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mizushima et al. [21] | Digestion | 2010 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 20 | 4,248 | 294 | CD | 39.0 | 30.6 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Palli et al. [22] | Gastroenterology | 2000 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | 1 | 19 | 10,592 2,716 7,877 |

920 231 689 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Pasternak et al. [34] | Am J Epidemiology | 2013 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 11 | 304,992 | 38,772 | IBD∗ | 47.0 | 55.0 | 4.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Selinger et al. [13] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2014 | Cohort | Referral center | Australia/New Zealand | 2 | 15 | 13,423 5,417 8,006 |

881 377 504 |

IBD CD UC |

31.5 29.0 34.0 |

53.1 59.1 47.1 |

||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| van Schaik et al. [35] | Gut | 2012 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 8 | 4,864 | 835 | IBD∗ | 43.0 | 57.0 | 2.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Venkataraman et al. [36] | Australian J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2005 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 25 | 4,901 | 532 | UC | 36.8 | 6.0 | 8.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Wandall et al. [37] | Scand J Gastroenterol | 2000 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 25 | 8,101 | 801 | UC | 41.0 | 44.8 | 10.1 | 15.9 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Winther et al. [19] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2004 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 35 | 22,290 | 1,160 | UC | 53.4 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yano et al. [14] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2013 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 25 | 10,552 | 770 | CD | 25.1 | 31.3 | 13.1 | |

∗Did not report separate incidence estimates for CD and UC.

(b).

| Author | Journal | Publication year | PSC (%) | Pancolitis (%) | Immunomodulator use (%) | Biologic use (%) | Observed number of CRCs | Incidence rate (per 100,000 persons) | Standard error | 95% CI lower bound | 95% CI upper bound | Bias rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askling et al. [25] | Gastroenterology | 2001 | 10.3 17.0 4.8 |

143 40 103 |

84.4 43.6 132.9 |

7.1 6.9 13.1 |

70.6 30.1 107.2 |

98.2 57.1 158.6 |

Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bernstein et al. [24] | Cancer | 2001 | 0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

60 24 36 |

146.3 112.5 183.1 |

18.9 23.0 30.5 |

109.3 67.5 123.3 |

183.3 157.5 242.9 |

Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Farrell et al. [26] | Gut | 2000 | 26.0 | 30.0 | 3 | 48.0 | 27.7 | −6.3 | 102.3 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fraser et al. [18] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2002 | 30.0 | 0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

23 4 19 |

41.5 19.5 54.5 |

8.7 9.8 12.5 |

24.5 0.4 30.0 |

58.5 38.6 79.0 |

Moderate | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Gillen et al. [27] | Gut | 1994 | 37 8 29 |

300.2 344.9 289.9 |

49.4 121.9 53.8 |

203.5 105.9 184.4 |

396.9 583.9 395.4 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Herrinton et al. [28] | Gastroenterology | 2012 | 82 29 53 |

132.7 101.9 159.0 |

14.7 18.9 21.8 |

104.0 64.8 116.2 |

161.4 139.0 201.8 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hou et al. [29] | Inflamm Bowel Dis | 2012 | 183 | 163.0 | 12.0 | 139.4 | 186.6 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [7] | Gastroenterology | 2012 | 338 70 268 |

87.7 53.7 105.0 |

4.8 6.4 6.4 |

78.4 41.1 92.4 |

97.0 66.3 117.6 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [39] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2004 | 4 | 60.9 | 30.4 | 1.2 | 120.6 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jussila et al. [10] | Scand J Gastroenterol | 2013 | 189 32 157 |

81.3 61.7 86.9 |

5.9 10.9 6.9 |

69.7 40.3 73.3 |

92.9 83.1 100.5 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lakatos et al. [38] | Inflamm Bowel Dis | 2006 | 2.9 | 25.8 | 13 | 151.8 | 42.1 | 69.3 | 234.3 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lakatos et al. [30] | J Crohn's Colitis | 2011 | 1.8 | 5 | 86.8 | 38.8 | 10.7 | 162.9 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lennard-Jones et al. [31] | Gut | 1990 | 22 | 543.5 | 115.9 | 316.4 | 770.6 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lovasz et al. [32] | J Gastroenterol Liver Dis | 2013 | 0.9 | 34.5 | 47.2 | 7.7 | 6 | 77.3 | 31.6 | 15.4 | 139.2 | Moderate |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Manninen et al. [11] | J Crohn's Colitis | 2013 | 2.5 1.1 3.2 |

43.2 37.7 49.4 |

21 5 16 |

91.7 68.8 102.3 |

20.0 30.8 25.6 |

52.5 8.5 52.2 |

130.9 129.1 152.4 |

Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mellemkjær et al. [33] | Cancer Causes Control | 2000 | 15 | 65.6 | 16.9 | 32.4 | 98.8 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mizushima et al. [21] | Digestion | 2010 | 12.4 | 6 | 141.2 | 57.6 | 28.2 | 254.2 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Palli et al. [22] | Gastroenterology | 2000 | 12 2 10 |

113.0 73.6 127.0 |

32.6 52.0 40.2 |

49.1 −28.4 48.3 |

176.9 175.6 205.7 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pasternak et al. [34] | Am J Epidemiology | 2013 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 380 | 124.6 | 6.4 | 112.1 | 137.1 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Selinger et al. [13] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2014 | 38.4 37.4 39.1 |

29 5 24 |

216.0 92.3 299.8 |

40.1 41.3 61.2 |

137.4 11.4 179.9 |

294.6 173.2 419.7 |

Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| van Schaik et al. [35] | Gut | 2012 | 29.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 | 185.0 | 61.7 | 64.1 | 305.9 | Moderate | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Venkataraman et al. [36] | Australian J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2005 | 44.0 | 5 | 102.0 | 45.6 | 12.6 | 191.4 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wandall et al. [37] | Scand J Gastroenterol | 2000 | 18.0 | 6 | 74.1 | 30.3 | 14.8 | 133.4 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Winther et al. [19] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2004 | 54.0 | 13 | 58.3 | 16.2 | 26.6 | 90.0 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Yano et al. [14] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2013 | 14.7 | 9 | 85.3 | 28.4 | 29.6 | 141.0 | Moderate | |||

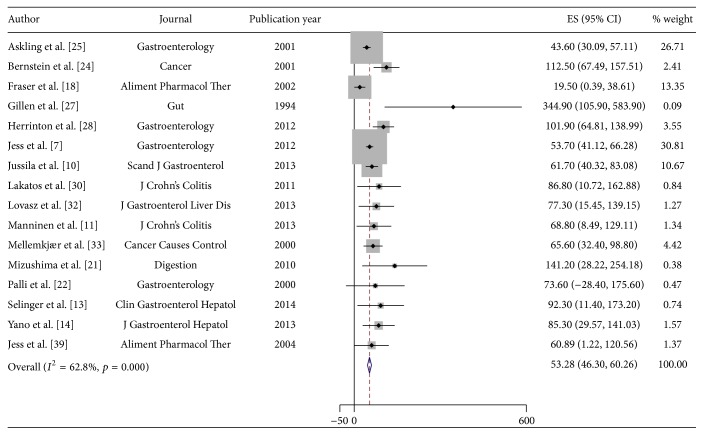

Reported CRC incidence rates in CD ranged from 19.5/100,000 py (95% CI 0.4–38.6/100,000) to 344.9/100,000 py (95% CI 105.9–583.9/100,000) (Table 1). Using a random effects model, an estimated incidence of CRC in CD of 53.3/100,000 py (95% CI 46.3–60.3/100,000) was obtained. Figure 2 displays the Forest plot for the pooled estimates. In UC, the reported incidence rates ranged from 54.5/100,000 py (95% CI 30.0–79.0/100,000) to 543.5/100,000 py (95% CI 316.4–770.6/100,000). Substantial heterogeneity was again present when pooling using a random effects model (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 110.7; p < 0.001; I 2 = 86.4%), and thus the results in UC were not pooled.

Figure 2.

Incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with Crohn's Disease (CD). Each incidence estimate is presented followed by the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Each square in the plot indicates the point estimate of the incidence. The diamond represents the summary incidence from the pooled studies. Error bars depict the 95% CIs.

Analyses stratified by publication year and region of origin did not reveal any significant differences in results. We also conducted metaregression analyses to evaluate the potential impact of age, gender, race, Montreal Classification, disease duration, surgical history, smoking status, comorbid primary sclerosing cholangitis, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, and concomitant treatment with immunosuppressants and/or biologics on the CRC incidence in IBD. Due to the limited sample size and incomplete reporting of demographic characteristics in many studies, these analyses were underpowered. Together, age, gender, and disease duration explained a significant proportion of the between-study variability (adjusted R 2 = 65.67%); however we could not make any further conclusions regarding the impact of these covariates on CRC incidence in IBD. Evaluation of funnel plots and Egger's test showed evidence of small study effects and/or publication bias for IBD overall (p = 0.149) and weak evidence of small study effects in CD and UC (p = 0.005 CD; p = 0.05 UC). However, the power of these tests may be compromised due to small sample sizes and significant heterogeneity between studies. Given the observational nature of the included studies and the probability of bias from small study effects, the overall quality of the CRC body of evidence per the GRADE approach is low.

3.1.2. Leukemia

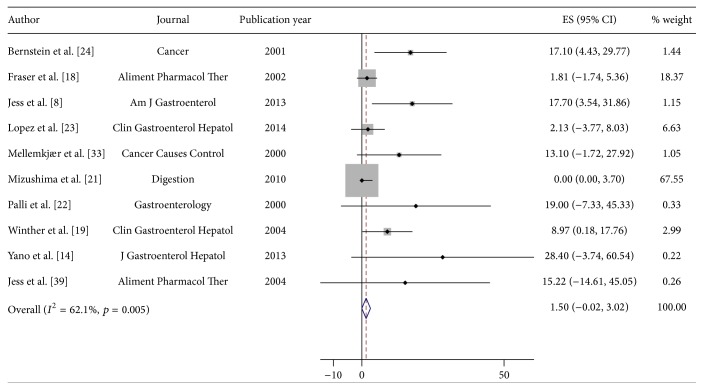

Reported incidence rates of leukemia in IBD ranged from 0.0/100,000 py (95% CI 0.0–3.7/100,000) to 28.4/100,000 py (95% CI −3.7–60.5/100,000) (Table 2). Using a random effects model, the pooled estimated incidence of leukemia in IBD of 1.5/100,000 py was obtained (95% CI −0.02–3.0/100,000). Figure 3 illustrates the Forest plot for the pooled estimates. Moderate between-study heterogeneity was seen (heterogeneity test chi2 = 23.8, p = 0.005; I 2 = 62.1%); however this is likely influenced by the small number of available studies. In CD, the range of reported incidence rates was identical to that of IBD (Table 2). In UC, reported incidence rates ranged from 8.97/100,000 py (95% CI 0.2–17.8/100,000) to 25.4/100,000 py (95% CI −9.8–60.6/100,000) (Table 2). The pooled incidence estimate was 0.3/100,000 py for CD (95% CI −1.0–1.6/100,000) and 13.0/100,000 py for UC (95% CI 5.8–20.3/100,000). The I 2 statistics are 44.3% (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 10.8, p = 0.096) and 0.0% (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 2.65, p = 0.449), respectively, indicating low levels of heterogeneity; however the power of this analysis is severely limited due to the small number of included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies of leukemia in IBD.

(a).

| Author | Journal | Publication year | Study design | Study population | Region of origin | Number of sites | Study duration (yrs) | Person-years | Number of patients | Diagnosis | Mean age (yrs) | Female (%) | Mean disease duration (yrs) | Surgery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernstein et al. [24] | Cancer | 2001 | Case-control | Administrative claims | Canada | Regionwide | 14 | 41,005 21,340 19,665 |

5,529 2,857 2,672 |

IBD CD UC |

39.0 36.3 41.7 |

54.5 59.0 50.0 |

||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Fraser et al. [18] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2002 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 35 | 55,388 | 1,578 | IBD∗ | 35.0 | 53.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [8] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2013 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | 1 | 32 | 33,843 11,261 22,582 |

2,211 774 1,437 |

IBD CD UC |

53.0 57.0 49.0 |

|||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [39] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2004 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 35 | 6,569 | 374 | CD | 58.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lopez et al. [23] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2014 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 3 | 23,457 | 10,810 | IBD∗ | 40.0 | 53.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mellemkjær et al. [33] | Cancer Causes Control | 2000 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 16 | 22,875 | 2,645 | CD | 50.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mizushima et al. [21] | Digestion | 2010 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 20 | 4,248 | 294 | CD | 39.0 | 30.6 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Palli et al. [22] | Gastroenterology | 2000 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | 1 | 19 | 10,592 2,716 7,877 |

920 231 689 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Winther et al. [19] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2004 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 35 | 22,290 | 1,160 | UC | 53.4 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yano et al. [14] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2013 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 25 | 10,552 | 770 | CD | 25.1 | 31.3 | 13.1 | |

(b).

| Author | Journal | Publication year | PSC (%) | Pancolitis (%) | Immunomodulator use (%) | Biologic use (%) | Observed number of leukemia cases | Incidence rate (per 100,000 persons) | Standard error | 95% CI lower bound | 95% CI upper bound | Bias rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernstein et al. [24] | Cancer | 2001 | 0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

7 3 4 |

17.1 14.1 20.3 |

6.5 8.1 10.2 |

4.4 −1.9 0.4 |

29.8 30.1 40.2 |

Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fraser et al. [18] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2002 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.81 | 1.8 | −1.7 | 5.4 | Moderate | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [8] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2013 | 26.7 41.0 19.0 |

27.2 45.0 18.0 |

6 1 5 |

17.7 8.9 22.1 |

7.2 8.9 9.9 |

3.5 −8.5 2.7 |

31.9 26.3 41.5 |

Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [39] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2004 | 1 | 15.2 | 15.2 | −14.6 | 45.1 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lopez et al. [23] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2014 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.13 | 3.0 | −3.8 | 8.0 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mellemkjær et al. [33] | Cancer Causes Control | 2000 | 3 | 13.1 | 7.6 | −1.7 | 27.9 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mizushima et al. [21] | Digestion | 2010 | 12.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.7 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Palli et al. [22] | Gastroenterology | 2000 | 2 0 2 |

19.0 0.0 25.4 |

13.4 18.0 |

−7.3 0.0 −9.8 |

45.3 3.7 60.6 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Winther et al. [19] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2004 | 54.0 | 4 | 8.97 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 17.8 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Yano et al. [14] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2013 | 14.7 | 3 | 28.4 | 16.4 | −3.7 | 60.5 | Moderate | |||

∗Did not report separate incidence measures for CD and UC.

Figure 3.

Incidence of leukemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Each incidence estimate is presented followed by the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Each square in the plot indicates the point estimate of the incidence. The diamond represents the summary incidence from the pooled studies. Error bars depict the 95% CIs.

Stratification by publication year and region did not impact the incidence estimates for IBD or for CD and UC separately. Furthermore, no significant effects of any study- or subject-level covariates on incidence estimates were discovered in metaregression analyses; however the small sample size again restricted the power of these tests.

As less than 10 studies were included, the interpretation of funnel plot symmetry and Egger's test to assess the presence of small study effects and/or publication bias are not recommended [52]. The overall quality of the leukemia body of evidence, per the GRADE approach, is low due to study designs and small sample size.

3.1.3. Lymphoma

Reported incidence rates for lymphoma in IBD ranged from 0.0/100,000 py (95% CI 0.0–3.7/100,000) to 81.7/100,000 py (95% CI 21.2–142.2/100,000) (Table 3). Substantial heterogeneity between studies prevented pooling of estimates (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 591.1; p < 0.001; I 2 = 96.6%). Thus, the included studies are presented as unpooled estimates. A sensitivity analysis excluding the two studies with the lowest individual incidence estimates and highest weights on the pooled estimates was conducted, with no significant corresponding decrease in heterogeneity [14, 21].

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies of lymphoma in IBD.

(a).

| Author | Journal | Publication year | Study design | Study population | Region of origin | Number of sites | Study duration (yrs) | Person-years | Number of patients | Diagnosis | Mean age (yrs) | Female (%) | Mean disease duration (yrs) | Surgery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbas et al. [40] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2012 | Cohort | National registry | United States | Countrywide | 11.0 | 352,429 | 32,039 | UC | 60.0 | 7.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Beaugerie et al. [41] | Lancet | 2009 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 3.0 | 22,706 10,899 11,807 |

10,810 5,153 5,657 |

IBD CD UC |

53.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Bernstein et al. [24] | Cancer | 2001 | Case-control | Administrative claims | Canada | Regionwide | 14.0 | 41,005 21,340 19,665 |

5,529 2,857 2,672 |

IBD CD UC |

39.0 36.3 41.7 |

54.5 59.0 50.0 |

||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Chiorean et al. [42] | Dig Dis Sci | 2011 | Case-control | Referral center | United States | 1 | 8.4 | 30,121 19,127 10,994 |

3,585 2,277 1,308 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Farrell et al. [26] | Gut | 2000 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | 1 | 9.0 | 6,256 | 782 | IBD∗ | 44.1 | 52.0 | 10.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Fraser et al. [18] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2002 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 35.0 | 55,388 20,494 34,894 |

1,578 584 994 |

IBD CD UC |

35.0 | 53.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Herrinton et al. [43] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2011 | Cohort | Administrative claims | United States | Regionwide | 13.0 | 67,867 | 16,023 | IBD∗ | 53.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [8] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2013 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | 1 | 32.0 | 33,843 11,261 22,582 |

2,211 774 1,437 |

IBD CD UC |

53.0 57.0 49.0 |

|||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [39] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2004 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 35.0 | 6,569 | 374 | CD | 58.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Jussila et al. [10] | Scand J Gastroenterol | 2013 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 23.0 | 232,536 51,876 180,660 |

20,970 4,983 15,987 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Khan et al. [44] | Gastroenterology | 2013 | Cohort | National registry | United States | Countrywide | 10.0 | 199,046 | 36,891 | UC | 60.0 | 7.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lakatos et al. [45] | J Crohn's Colitis | 2012 | Cohort | Provincial registry | Europe (Eastern) | 7 | 31.0 | 19,293 7,093 12,830 |

1,420 506 914 |

IBD CD UC |

32.5 28.5 36.5 |

48.8 50.0 47.6 |

22.8 41.3 4.2 |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Lewis et al. [46] | Gastroenterology | 2001 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 9.0 | 64,239 24,221 40,018 |

16,996 6,605 10,391 |

IBD CD UC |

47.3 44.3 50.3 |

54.0 58.0 50.0 |

||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Loftus Jr. et al. [47] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2000 | Cohort | Regional registry | United States | 2 | 53.0 | 6,662 3,150 3,512 |

454 216 238 |

IBD CD UC |

24.0 | 14.9 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mellemkjær et al. [33] | Cancer Causes Control | 2000 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 16.0 | 22,875 | 2,645 | CD | 50.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mizushima et al. [21] | Digestion | 2010 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 20.0 | 4,248 | 294 | CD | 39.0 | 30.6 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Palli et al. [22] | Gastroenterology | 2000 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | 1 | 19.0 | 10,592 2,716 7,877 |

920 231 689 |

IBD CD UC |

||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Pasternak et al. [34] | Am J Epidemiology | 2013 | Cohort | National registry | Europe (Western) | Countrywide | 11.0 | 304,992 | 38,772 | IBD∗ | 47.0 | 55.0 | 4.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Van Domselaar et al. [48] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2010 | Cohort | Referral center | Europe (Western) | 1 | 8,563 | 911 | IBD∗ | 53.0 | 28.6 | 4.8 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Winther et al. [19] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2004 | Cohort | Regional registry | Europe (Western) | Regionwide | 35.0 | 22,290 | 1,160 | UC | 53.4 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yano et al. [14] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2013 | Cohort | Referral center | Asia | 1 | 25.0 | 10,552 | 770 | CD | 25.1 | 31.3 | 13.1 | |

(b).

| Author | Journal | Publication year | PSC (%) | Pancolitis (%) | Immunomodulator use (%) | Biologic use (%) | Observed number of lymphomas | Incidence rate (per 100,000 persons) | Standard error | 95% CI lower bound | 95% CI upper bound | Bias rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbas et al. [40] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2012 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 282 | 80.0 | 4.8 | 70.7 | 89.3 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Beaugerie et al. [41] | Lancet | 2009 | 29.6 13.0 16.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

6 3 3 |

26.4 27.5 25.4 |

10.8 15.9 14.7 |

5.3 −3.6 −3.3 |

47.5 58.6 54.1 |

Moderate | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bernstein et al. [24] | Cancer | 2001 | 0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

16 9 7 |

39.0 42.2 35.6 |

9.8 14.1 13.5 |

19.9 14.6 9.2 |

58.1 69.8 62.0 |

Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Chiorean et al. [42] | Dig Dis Sci | 2011 | 8 5 3 |

26.6 26.1 27.3 |

9.4 11.7 15.8 |

8.2 3.2 −3.6 |

45.0 49.0 58.2 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Farrell et al. [26] | Gut | 2000 | 26.0 | 30.0 | 4 | 64.0 | 32.0 | 1.3 | 126.7 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fraser et al. [18] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2002 | 30.0 | 0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

5 1 4 |

9.0 4.87 11.5 |

4.0 4.9 5.8 |

1.1 −4.7 0.2 |

16.9 14.4 22.8 |

Moderate | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Herrinton et al. [43] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2011 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33 | 48.6 | 8.5 | 32.0 | 65.2 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [8] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2013 | 26.7 41.0 19.0 |

27.2 45.0 18.0 |

15 7 8 |

44.3 62.2 35.4 |

11.4 23.5 12.5 |

21.9 16.1 10.9 |

66.7 108.3 59.9 |

Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jess et al. [39] | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 2004 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.7 | Moderate | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Jussila et al. [10] | Scand J Gastroenterol | 2013 | 72 14 58 |

31.0 27.0 32.1 |

3.7 7.2 4.2 |

23.8 12.9 23.8 |

38.2 41.1 40.4 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Khan et al. [44] | Gastroenterology | 2013 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 119 | 60.0 | 5.5 | 49.2 | 70.8 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lakatos et al. [45] | J Crohn's Colitis | 2012 | 2.3 1.8 2.7 |

30.2 35.9 24.4 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 |

3 1 2 |

15.5 14.1 15.6 |

8.9 14.1 11.0 |

−2.0 −13.5 −6.0 |

33.0 41.7 37.2 |

Moderate |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lewis et al. [46] | Gastroenterology | 2001 | 9.5 13.0 6.0 |

18 7 11 |

28.0 28.9 27.5 |

6.6 10.9 8.3 |

15.1 7.5 11.2 |

40.9 50.3 43.8 |

Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Loftus Jr. et al. [47] | Am J Gastroenterol | 2000 | 1 1 0 |

15.0 32.0 0.0 |

15.0 32.0 |

−14.4 −30.7 0.0 |

44.4 94.7 3.7 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mellemkjær et al. [33] | Cancer Causes Control | 2000 | 4 | 17.5 | 8.8 | 0.4 | 34.7 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mizushima et al. [21] | Digestion | 2010 | 12.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.7 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Palli et al. [22] | Gastroenterology | 2000 | 7 1 6 |

66.0 36.8 76.2 |

24.9 36.8 31.1 |

17.1 −35.3 15.2 |

114.9 108.9 137.2 |

Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pasternak et al. [34] | Am J Epidemiology | 2013 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46 | 15.1 | 2.2 | 10.7 | 19.5 | Moderate | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Van Domselaar et al. [48] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2010 | 7 | 81.7 | 30.9 | 21.2 | 142.2 | Moderate | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Winther et al. [19] | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2004 | 54.0 | 2 | 17.9 | 12.7 | −6.9 | 42.8 | Moderate | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Yano et al. [14] | J Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2013 | 14.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.7 | Moderate | ||||

∗Did not report separate incidence estimates for CD and UC.

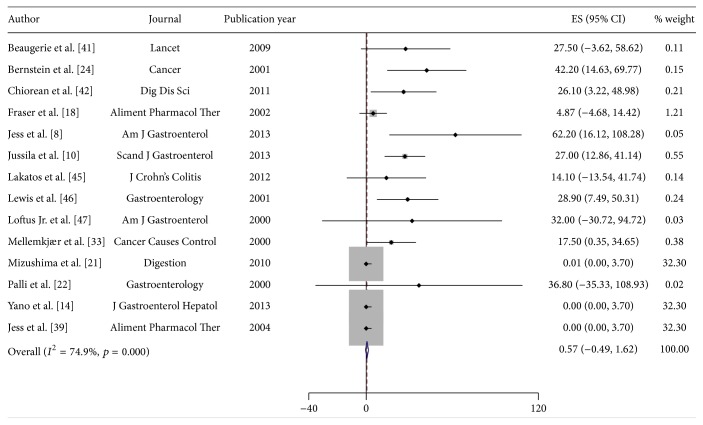

Reported incidence rates of lymphoma in CD ranged from 0.0/100,000 py (95% CI 0.0–3.7/100,000) to 62.2/100,000 py (95% CI 16.1–108.3/100,000) (Table 3). For UC, the incidence rates ranged from 0.0/100,000 py (95% CI 0.0–3.7/100,000) to 76.2/100,000 py (95% CI 15.2–137.2/100,000) (Table 3). A pooled incidence rate of 0.6/100,000 py (95% CI −0.5–1.6/100,000) for CD was obtained. Substantial heterogeneity prevented pooling of estimates for UC (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 199.5; p < 0.001; I 2 = 94.5%). A sensitivity analysis excluding the study with the largest impact on the pooled estimate in UC [47] decreased the heterogeneity (heterogeneity test, chi2 = 44.79; p < 0.001; I 2 = 77.7%). However, substantial heterogeneity remained, and results for UC are presented as unpooled estimates (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Incidence of lymphoma in patients with Crohn's Disease (CD). Each incidence estimate is presented followed by the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Each square in the plot indicates the point estimate of the incidence. The diamond represents the summary incidence from the pooled studies. Error bars depict the 95% CIs.

Incidence estimates stratified by publication year and region did not differ. Metaregression analysis revealed a statistically significant effect of age on lymphoma incidence in IBD. For each mean year increase in age, the incidence of lymphoma increased by approximately 2.1/100,000 py (95% CI 0.74–3.4/100,000), explaining approximately 65.8% of the between-study heterogeneity (adjusted R 2 = 65.8%). No other covariate effects were found in metaregression analyses.

There was weak evidence of publication bias and/or small study effects in the IBD analysis (p = 0.213) and in the UC analysis (p = 0.824). The number of included studies for CD is less than 10; thus analyses of funnel plots and Egger's test are not recommended [52]. The overall quality of the lymphoma body of evidence, per the GRADE approach, is low due to the observational designs of available studies.

3.2. Discussion

This meta-analysis was performed in order to produce updated and reliable incidence rates for CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in IBD patients and in CD and UC separately. We aimed to quantify cancer incidence associated with underlying IBD, without the effects of immunomodulator and biologic pharmacotherapy, but this was difficult without reliable reporting of treatment information in the available studies. Although we could not pool estimates of the incidence of CRC in IBD and UC specifically, a pooled incidence rate of 53.3/100,000 py (95% CI 46.3–60.3/100,000) in CD was obtained. The estimated worldwide CRC incidence rate is 19.3/100,000 py [53]. In more developed regions of the world, which compares to the regions of origin of the included studies, the incidence rate is higher at 59.2/100,000 py [53]. As such, CRC incidence in CD does not appear to be higher than that of the general population in similar areas of origin. Of note, these incidence estimates are crude (not age-adjusted) and therefore may not reflect differences in the age of the underlying populations.

For leukemia, pooled incidence rates of 1.5/100,000 py (95% CI −0.06–3.0/100,000), 0.3/100,000 py (95% CI −1.0–1.6/100,000), and 13.0/100,000 py (95% CI 5.8–20.3/100,000) were obtained for IBD, CD, and UC, respectively. The estimated worldwide leukemia incidence is 5.0/100,000 py and 11.3/100,000 py in developed regions [53]. Thus, the incidence of leukemia in IBD and CD is lower than that of the general population in developed regions but is slightly higher in UC. For lymphoma, substantial heterogeneity prevented the pooling of estimates for IBD and UC; however a pooled incidence rate of 0.6/100,000 py (95% CI −0.4–2.1/100,000) in CD was obtained. Estimated worldwide lymphoma incidence is 6.4/100,000 py and 17.6/100,000 py in more developed areas [53]. Thus, the incidence of lymphoma in CD is lower than estimated both worldwide and in developed regions.

Due to incomplete reporting of use of immunomodulators and biologics in the published literature, we could not calculate incidence rates of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma specifically in persons not treated with these medications; however incidence estimates stratified by publication year before and after widespread use of these medications were not significantly different. This suggests that the impact of immunomodulators and biologics on the incidence of these cancers may be negligible. Metaregression did not reveal any significant subject- or study-level covariate effects in the majority of analyses, with the exception of the effect of mean age on the incidence of lymphoma in IBD. The power of these tests was limited by incomplete reporting of these variables and the small number of included studies.

The strength of the present study is the comprehensiveness of the literature search and evaluation of data for inclusion. Despite the exhaustiveness of the search, we could include only a small number of studies, limiting the power of the pooled analyses and ultimate confidence in incidence estimates. In addition, substantial heterogeneity prevented pooling of estimates in some cases. The heterogeneity of the included studies may reflect differences in follow-up time, cohort size, geographic differences in patient care, or other factors that we were unable to assess due to incomplete reporting in the published literature. Although these limitations may lead to bias in our incidence estimates, the direction of which is indeterminable, our estimates are based on the best available evidence.

4. Conclusions

This meta-analysis presents updated estimates of the incidence of CRC, leukemia, and lymphoma in adults with IBD. Overall, the incidence of these malignancies does not appear to be higher than in the general population. Further research is needed to explore patient characteristics that may modify the risk of malignancy. Specifically, we need large population based cohort studies in IBD patients that report complete demographic and outcome data. Detailed information on immunomodulator and biologic use is limited in the published literature, and if we are to be able to truly understand the potential increased risk of malignancy associated with IBD pharmacotherapy, this information is required.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 details the search algorithms used for the systematic review. The search algorithm specific to each source are listed along with the number of results returned.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

Colorectal cancer

- IBD:

Inflammatory bowel disease

- PSC:

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- LD:

Lymphoproliferative disorders

- CD:

Crohn's Disease

- UC:

Ulcerative colitis

- CI:

Confidence interval

- py:

Person-years.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dyson J. K., Rutter M. D. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: what is the real magnitude of the risk? World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;18(29):3839–3848. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i29.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim E. R., Chang D. K. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the risk, pathogenesis, prevention and diagnosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(29):9872–9881. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triantafillidis J. K., Nasioulas G., Kosmidis P. A. Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies. Anticancer Research. 2009;29(7):2727–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baars J. E., Kuipers E. J., van Haastert M., Nicolaï J. J., Poen A. C., van der Woude C. J. Age at diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease influences early development of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a nationwide, long-term survey. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;47(12):1308–1322. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0603-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron V., Vienne A., Sokol H., et al. Risk factors for neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease patients with pancolitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(11):2405–2411. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos F. G., Teixeira M. G., Scanavini A., Almeida M. G. D., Nahas S. C., Cecconello I. Intestinal and extraintestinal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a tertiary care hospital. Arquivos de Gastroenterologia. 2013;50(2):123–129. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032013000200021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jess T., Simonsen J., Jorgensen K. T., Pedersen B. V., Nielsen N. M., Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):375–381. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jess T., Horváth-Puhó E., Fallingborg J., Rasmussen H. H., Jacobsen B. A. Cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease according to patient phenotype and treatment: a danish population-based cohort study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(12):1869–1876. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson C. M., Wei C., Ensor J. E., et al. Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Causes and Control. 2013;24(6):1207–1222. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0201-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jussila A., Virta L. J., Pukkala E., Färkkilä M. A. Malignancies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide register study in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;48(12):1405–1413. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.846402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manninen P., Karvonen A.-L., Huhtala H., et al. The risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in Finland: a follow-up of 20 years. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2013;7(11):e551–e557. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imam M. H., Thackeray E. W., Lindor K. D. Colonic neoplasia in young patients with inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Colorectal Disease. 2013;15(2):198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selinger C. P., Andrews J. M., Titman A., et al. Long-term follow-up reveals low incidence of colorectal cancer, but frequent need for resection, among Australian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(4):644–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano Y., Matsui T., Hirai F., et al. Cancer risk in Japanese Crohn's disease patients: investigation of the standardized incidence ratio. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;28(8):1300–1305. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magro F., Peyrin-Biroulet L., Sokol H., et al. Extra-intestinal malignancies in inflammatory bowel disease: results of the 3rd ECCO Pathogenesis Scientific Workshop (III) Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2014;8(1):31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason M., Siegel C. A. Do inflammatory bowel disease therapies cause cancer? Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2013;19(6):1306–1321. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182807618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sokol H., Beaugerie L. Inflammatory bowel disease and lymphoproliferative disorders: the dust is starting to settle. Gut. 2009;58(10):1427–1436. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.181982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser A. G., Orchard T. R., Robinson E. M., Jewell D. P. Long-term risk of malignancy after treatment of inflammatory bowel disease with azathioprine. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2002;16(7):1225–1232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winther K. V., Jess T., Langholz E., Munkholm P., Binder V. Long-term risk of cancer in ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study from Copenhagen County. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;2(12):1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen N., Duricova D., Elkjaer M., Gamborg M., Munkholm P., Jess T. Risk of extra-intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(7):1480–1487. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizushima T., Ohno Y., Nakajima K., et al. Malignancy in Crohn's disease: incidence and clinical characteristics in Japan. Digestion. 2010;81(4):265–270. doi: 10.1159/000273784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palli D., Trallori G., Bagnoli S., et al. Hodgkin's disease risk is increased in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):647–653. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez A., Mounier M., Bouvier A.-M., et al. Increased risk of acute myeloid leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes in patients who received thiopurine treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(8):1324–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein C. N., Blanchard J. F., Kliewer E., Wajda A. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91(4):854–862. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:4<854::aid-cncr1073>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Askling J., Dickman P. W., Karlén P., et al. Family history as a risk factor for colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(6):1356–1362. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrell R. J., Ang Y., Kileen P., et al. Increased incidence of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in inflammatory bowel disease patients on immunosuppressive therapy but overall risk is low. Gut. 2000;47(4):514–519. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillen C. D., Walmsley R. S., Prior P., Andrews H. A., Allan R. N. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: a comparison of the colorectal cancer risk in extensive colitis. Gut. 1994;35(11):1590–1592. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrinton L. J., Liu L., Levin T. R., Allison J. E., Lewis J. D., Velayos F. Incidence and mortality of colorectal adenocarcinoma in persons with inflammatory bowel disease from 1998 to 2010. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):382–389. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou J. K., Kramer J. R., Richardson P., Mei M., El-Serag H. B. Risk of colorectal cancer among Caucasian and African American veterans with ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18(6):1011–1017. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakatos P. L., David G., Pandur T., et al. Risk of colorectal cancer and small bowel adenocarcinoma in Crohn's disease: a population-based study from western Hungary 1977–2008. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2011;5(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lennard-Jones J. E., Melville D. M., Morson B. C., Ritchie J. K., Williams C. B. Precancer and cancer in extensive ulcerative colitis: findings among 401 patients over 22 years. Gut. 1990;31(7):800–806. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.7.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovasz B. D., Lakatos L., Golovics P. A., et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in Crohn's disease patients with colonic involvement and stenosing disease in a population-based cohort from Hungary. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2013;22(3):265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellemkjær L., Johansen C., Gridley G., Linet M. S., Kjær S. K., Olsen J. H. Crohn's disease and cancer risk (Denmark) Cancer Causes and Control. 2000;11(2):145–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1008988215904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasternak B., Svanström H., Schmiegelow K., Jess T., Hviid A. Use of azathioprine and the risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;177(11):1296–1305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Schaik F. D. M., van Oijen M. G. H., Smeets H. M., van der Heijden G. J. M. G., Siersema P. D., Oldenburg B. Thiopurines prevent advanced colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2012;61(2):235–240. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.237412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkataraman S., Mohan V., Ramakrishna B. S., et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis in India. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia) 2005;20(5):705–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wandall E. P., Damkier P., Møller Pedersen F., Wilson B., Schaffalitzky De Muckadell O. B. Survival and incidence of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis in funen county diagnosed between 1973 and 1993. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;35(3):312–317. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lakatos L., Mester G., Erdelyi Z., et al. Risk factors for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in a Hungarian cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis: results of a population-based study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2006;12(3):205–211. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000217770.21261.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jess T., Winther K. V., Munkholm P., Langholz E., Binder V. Intestinal and extra-intestinal cancer in Crohn's disease: follow-up of a population-based cohort in Copenhagen County, Denmark. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2004;19(3):287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbas A., Koleva Y., Khan N. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for ulcerative colitis: a nationwide 10-year retrospective cohort from the veterans affairs healthcare system. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107, article S693 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beaugerie L., Brousse N., Bouvier A. M., et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2009;374(9701):1617–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiorean M. V., Pokhrel B., Adabala J., Helper D. J., Johnson C. S., Juliar B. Incidence and risk factors for lymphoma in a single-center inflammatory bowel disease population. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2011;56(5):1489–1495. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1430-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herrinton L. J., Liu L., Weng X., Lewis J. D., Hutfless S., Allison J. E. Role of thiopurine and anti-TNF therapy in lymphoma in inflammatory bowel disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106(12):2146–2153. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan N., Abbas A. M., Lichtenstein G. R., Loftus E. V., Jr., Bazzano L. A. Risk of lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with thiopurines: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(5):1007.e3–1015.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lakatos L., Golovics P. A., Lovasz B. D., et al. Sa1247 Low risk of lymphoma in inflammatory bowel diseases in Western Hungary. Results from a population-based incident cohort. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5, supplement 1):p. S-253. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(12)60954-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis J. D., Bilker W. B., Brensinger C., Deren J. J., Vaughn D. J., Strom B. L. Inflammatory bowel disease is not associated with an increased risk of lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(5):1080–1087. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loftus E. V., Jr., Tremaine W. J., Habermann T. M., Harmsen W. S., Zinsmeister A. R., Sandborn W. J. Risk of lymphoma in inflammatory bowel disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95(9):2308–2312. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(00)01108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Domselaar M., López San Román A., Bastos Oreiro M., Garrido Gómez E. Lymphoproliferative disorders in an inflammatory bowel disease unit. Gastroenterologia y Hepatologia. 2010;33(1):12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sterne J., Higgins J., Reeves B. A Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool: For Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI) Version 1.0.0 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higgins J. P. T., Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins J., Deeks J., Altman D. Special Topics in Statistics. chapter 16. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. (The Cochrane Book). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer T. M., Sterne J. A. C., editors. Meta-Analysis in Stata: An Updated Collection from the Stata Journal. Station, Tex, USA: Stata Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Ervik M., et al. IARC Cancer Base. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 details the search algorithms used for the systematic review. The search algorithm specific to each source are listed along with the number of results returned.