Abstract

Rotenone, a neurotoxic pesticide, induces loss of dopaminergic neurons related to Parkinson's disease. Previous studies have shown that rotenone induces neuronal apoptosis partly by triggering hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-dependent suppression of mTOR pathway. However, the underlying mechanism is not fully understood. Here, we show that rotenone elevates intracellular free calcium ion ([Ca2+]i) level, and activates CaMKII, resulting in inhibition of mTOR signaling and induction of neuronal apoptosis. Chelating [Ca2+]i with BAPTA/AM, preventing extracellular Ca2+ influx using EGTA, inhibiting CaMKII with KN93, or silencing CaMKII significantly attenuated rotenone-induced H2O2 production, mTOR inhibition, and cell death. Interestingly, using TTFA, antimycin A, catalase or Mito-TEMPO, we found that rotenone-induced mitochondrial H2O2 also in turn elevated [Ca2+]i level, thereby stimulating CaMKII, leading to inhibition of mTOR pathway and induction of neuronal apoptosis. Expression of wild type mTOR or constitutively active S6K1, or silencing 4E-BP1 strengthened the inhibitory effects of catalase, Mito-TEMPO, BAPTA/AM or EGTA on rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation, CaMKII phosphorylation and neuronal apoptosis. Together, the results indicate that the crosstalk between Ca2+ signaling and mitochondrial H2O2 is required for rotenone inhibition of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways. Our findings suggest that how to control over-elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and overproduction of mitochondrial H2O2 may be a new approach to deal with the neurotoxicity of rotenone.

Keywords: rotenone, apoptosis, calcium ion, CaMKII, H2O2, mTOR, Pathology

INTRODUCTION

Rotenone, a well-known neurotoxic pesticide, is highly lipophilic and easily traverses the blood-brain barrier and cellular membranes without depending upon dopamine transporters for access to the cytoplasm of neurons [1, 2]. Once inside cells, rotenone impedes mitochondrial function leading to intracellular oxidative stress [3, 4]. Rotenone induces apoptosis by increasing generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) in HL-60 and other cells [5]. Mitochondrial enzyme deficiency in rat brain is correlated with the generation of free radicals post administration of rotenone [6]. Mounting studies have demonstrated that rotenone contributes to decreased ATP synthesis, mitochondrial depolarization, and ROS generation via inhibiting mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I [3, 4]. Excessive ROS in turn will further inhibit complex I [7]. The vicious cycle eventually causes apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons, leading to Parkinson's disease (PD) [7-14]. Thus, rotenone is a possible etiological factor in PD. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the neurotoxicity of rotenone is still not fully understood.

Calcium ion (Ca2+) is important for many cellular events, such as proliferation/growth, differentiation, development and cell death [15]. When properly controlled, Ca2+ fluxes across the plasma membrane and between intracellular compartments play critical roles in fundamental functions of neurons, including the regulation of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis, synaptic transmission and plasticity, and cell survival [16]. However, disturbances in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis cause synaptic dysfunction, impaired plasticity and neuronal degeneration [16-19]. Especially, abnormally high levels of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) induces overproduction of free radicals such as ROS, which can activate stress cascades, resulting in apoptosis [20, 21]. In turn, excessive or sustained ROS can also exacerbate Ca2+ overload and sensitize the bioactivity of Ca2+ [20, 22, 23]. The interconnection between Ca2+ and ROS alters the structures and functions of cellular proteins, and also activates or inhibits related signaling pathways, leading to neuronal apoptosis [20, 24-27].

Mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) protein kinase, regulates differentiation, development and survival in neurons [28-30]. Thus, mTOR exerts a crucial role in synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, and food uptake in adult brain [28-30]. Increasing evidence reveals that mTOR could be activated or inhibited depending on the pathologic status of the nervous system, e.g. brain tumors, tuberous sclerosis, cortical dysplasia and neurodegenerative diseases such as PD, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and Huntington's disease (HD) [28, 30]. Our group has observed that cadmium, a heavy metal polluted in the environment, induces neuronal cell death by [Ca2+]i- and/or ROS-dependent activation of mTOR signaling [31-34], whereas hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a major radical of ROS, elicits neuronal cell death via suppression of mTOR pathway [35]. Recently, we have also found that rotenone evokes neuronal apoptosis via H2O2-dependent inhibition of mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of ribosomal p70 S6 kinase (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) [14, 36]. Intracellular Ca2+ elevation is a major factor for rotenone-induced apoptosis in neuronal cells [37]. Hence, in this study, we investigated whether rotenone induces apoptosis by Ca2+/ROS-dependent inhibition of mTOR pathway.

RESULTS

Rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with its induction of [Ca2+]i elevation

Increased [Ca2+]i levels have been documented in many experimental models of apoptosis [37-39]. To understand how Ca2+ signaling participates in rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis, first of all, we investigated the relationship between the [Ca2+]i level and the apoptosis in our neuronal cell models treated with rotenone. After PC12 cells and mouse primary neurons were treated with 0-1 μM rotenone for 24 h, [Ca2+]i was measured by using an intracellular Ca2+ indicator dye, Fluo-3/AM. We found that rotenone elicited strong [Ca2+]i fluorescence (in green) (Figure S1A), and the intensity of the fluorescence was rotenone concentration-dependent (Figure 1A). Concurrently, rotenone decreased cell viability (Figure 1B), and increased nuclear fragmentation and condensation (arrows), a hallmark of apoptosis [40], as well as TUNEL-positive cells (in green) in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Figure S1B, Figure 1C and 1D), respectively. Besides, treatment with rotenone for 24 h induced robust cleavages of caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in the cells (data not shown). Collectively, these data imply that rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with the induction of [Ca2+]i elevation.

Figure 1. Rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation is associated with cell viability reduction and apoptosis in neuronal cells.

PC12 cells and primary neurons were treated with rotenone (0-1 μM) for 24 h. [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensity was imaged and quantified using an intracellular Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-3/AM (A). Cell viability was determined by the MTS assay (B) and cell apoptosis was assayed using DAPI and TUNEL staining (C, D). A.-D. Rotenone concentration-dependently elicited [Ca2+]i elevation (A), and induced viability reduction (B) and apoptosis (C, D) in PC12 cells and primary neurons. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, difference with control group.

Rotenone elicits neuronal apoptosis via Ca2+-mediated inhibition of mTOR pathway

Our recent studies have shown that rotenone induces neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting mTOR pathway [36]. Having observed that rotenone-elevated [Ca2+]i is involved in neuronal apoptosis (Figure 1), next we asked whether the elevation of [Ca2+]i is responsible for rotenone-induced inhibition of mTOR signaling and apoptosis of neuronal cells. To this end, PC12 cells and primary neurons were treated with/without rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without 1,2-bis (2-amino-phenoxy)ethane-N,N,N,N-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA/AM, 30 μM), an intracellular Ca2+ chelator, for 1 h. We found that BAPTA/AM significantly attenuated rotenone-triggered [Ca2+]i elevation (Figure 2A) and substantially prevented rotenone from inhibiting the phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Figure 2B). Rotenone-induced cleavage of caspase-3 was also remarkably inhibited by BAPTA/AM (Figure 2B). In line with this, BAPTA/AM markedly prevented rotenone-induced cell viability reduction (Figure S2A), nuclear fragmentation and condensation (Figure 2C) in PC12 cells and primary neurons as well. The results suggest that rotenone-elevated [Ca2+]i contributes to inhibition of mTOR pathway and induction of neuronal apoptosis.

Figure 2. Rotenone elicits neuronal apoptosis via Ca2+-mediated inhibition of mTOR pathway.

PC12 cells and primary neurons were pretreated with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM) or EGTA (100 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h. [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensity was imaged and quantified using an intracellular Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-3/AM (A, D), Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies (B, E). The blots were probed for β-tubulin as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Cell apoptosis was assayed using DAPI staining (C, F). A.-F. Pretreatment with BAPTA/AM or EGTA significantly attenuated elevation of [Ca2+]i level (A, D) and inhibition of phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (B, E) in PC12 cells and primary neurons induced by rotenone, and obviously recused the cells from rotenone-induced cleaved-caspase-3 (B, E) and apoptosis (C, F). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). aP < 0.05, difference with control group; bP < 0.05, difference with 0.5 μM rotenone group; cP < 0.05, difference with 1 μM rotenone group.

To further define the role of rotenone-elevated [Ca2+]i in suppressing mTOR pathway, we extended our studies using ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid (EGTA, 100 μM), an extracellular Ca2+ chelator. The results showed that inhibition of extracellular Ca2+ influx by EGTA profoundly prevented rotenone-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i (Figure 2D) and inhibition of phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Figure 2E) in PC12 cells and primary neurons. Furthermore, EGTA also partially blocked rotenone-induced cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 2E), viability reduction (Figure S2B) and apoptosis (Figure 2F) in the cells. The results indicate that rotenone-induced extracellular Ca2+ influx is involved in inhibition of mTOR pathway leading to neuronal apoptosis. Our findings strongly support the notion that rotenone elicits neuronal apoptosis via Ca2+-mediated inhibition of mTOR pathway.

Rotenone elicits Ca2+-dependent CaMKII phosphorylation leading to inhibition of mTOR pathway and neuronal apoptosis

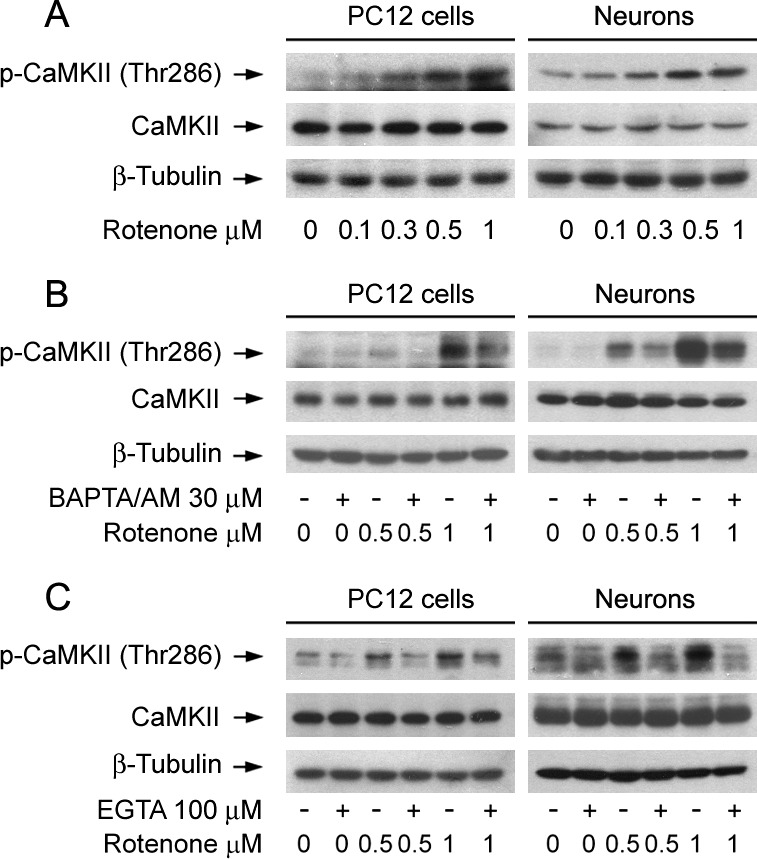

CaMKII is a general integrator of Ca2+ signaling, which is activated by Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM) complex [41, 42]. To determine the role of CaMKII activity in rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis, PC12 cells and primary neurons were exposed to 0-1 μM rotenone for 24 h. We found that rotenone induced phosphorylation of CaMKII in a concentration-dependent manner in the cells (Figure 3A). This was in agreement with decreased cell viability (Figure 1B) or increased apoptosis (Figure S1B, Figure 1C and 1D) in PC12 cells and primary neurons induced by rotenone exposure, suggesting that rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis might involve induction of CaMKII phosphorylation.

Figure 3. Rotenone triggers Ca2+-dependent CaMKII phosphorylation in neuronal cells.

PC12 cells and primary neurons were treated with rotenone (0-1 μM) for 24 h, or pretreated with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM) or EGTA (100 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies (A-C). The blots were probed for β-tubulin as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. A. Rotenone resulted in phospho-CaMKII increase in a concentration-dependent manner in the cells. B., C. Pretreatment with BAPTA/AM and EGTA obviously inhibited rotenone-induced CaMKII phosphorylation in the cells, respectively.

Next, we studied whether rotenone induces phosphorylation of CaMKII is dependent on the level of [Ca2+]i. For this, PC12 cells and primary neurons were pre-incubated with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM) or EGTA (100 μM) for 1 h, and then treated with/without rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h, respectively. As predicted, chelating [Ca2+]i with BAPTA/AM or preventing [Ca2+]i elevation using EGTA obviously inhibited rotenone-induced CaMKII phosphorylation in the cells (Figure 3B and 3C), indicating that rotenone-elevated [Ca2+]i contributes to CaMKII phosphorylation.

To determine whether rotenone-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII contributes to inhibiting mTOR pathway and inducing apoptosis in neuronal cells, PC12 cells and primary neurons were pre-treated with CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (10 μM) for 1 h, and then exposed to rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h. We observed that rotenone-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII was obviously attenuated by KN93 in the cells (Figure 4A). Of importance, rotenone-inhibited phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K and 4E-BP1, as well as rotenone-activated caspase-3 were markedly prevented by KN93 (Figure 4A). Furthermore, KN93 also partially protected cell viability (Figure S3A), and significantly suppressed rotenone-induced nuclear fragmentation and condensation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Pharmacological inhibition of CaMKII or downregulation of CaMKII partially prevents rotenone-induced inhibition of mTOR signaling and apoptosis in neuronal cells.

PC12 cells and primary neurons, or PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII or GFP (as control), were treated with rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h, or pretreated with/without KN93 (10 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies (A, C, D) The blots were probed for β-tubulin as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Cell apoptosis was assayed using DAPI staining (B, E). A., B. Inhibition of CaMKII by KN93 partially prevented inhibition of mTOR, S6K and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, cleavage of-caspase-3 (A) and apoptosis (B) in the cells induced by rotenone. C.-E. Lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII, but not to GFP, down-regulated CaMKII expression by ∼90% in PC12 cells (C), which obviously attenuated retonone-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII, and conferred partial resistance to rotenone-induced inhibition of mTOR signaling and activation of caspase-3 (D), as well as apoptosis (E) in the cells. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). aP < 0.05, difference with control group; bP < 0.05, difference with 0.5 μM rotenone group; cP < 0.05, difference with 1 μM rotenone group; dP < 0.05, CaMKII shRNA group versus GFP shRNA group.

To verify the role of CaMKII in rotenone suppression of mTOR pathway and neuronal apoptosis, the expression of CaMKIIα was silenced by RNA interference. As shown in Figure 4C, lentiviral shRNA to CaMKIIα, but not to GFP, downregulated CaMKII expression by ∼90% in PC12 cells. Silencing CaMKII obviously attenuated rotenone-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII (Figure 4D), and conferred partial resistance to rotenone-induced inhibition of phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Figure 4D). Consistently, downregulation of CaMKII also attenuated rotenone-induced cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 4D), as well as cell viability reduction (Figure S3B) and apoptosis (Figure 4E). The results clearly indicate that rotenone inhibits mTOR signaling pathway and neuronal apoptosis by elevating Ca2+-dependent CaMKII phosphorylation.

Rotenone evokes Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent induction of H2O2 overproduction in neuronal cells

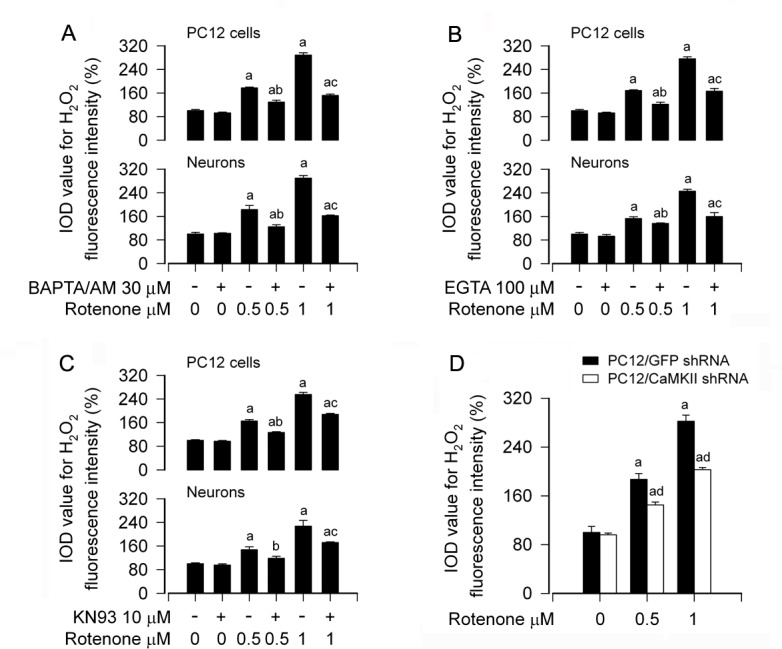

Recently we have demonstrated that rotenone elicits H2O2 generation contributing to neuronal apoptosis [14]. In this study, we have noticed that rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation results in apoptosis of PC12 cells and primary neurons (Figures 1 and 2). Therefore, next we sought to test whether rotenone-elevated [Ca2+]i contributes to H2O2 production and consequential apoptosis. To this end, PC12 cells and primary neurons were pretreated with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM) or EGTA (100 μM) for 1 h, and then exposed to 0.5 and 1 μM rotenone for 24 h, followed by imaging H2O2 fluorescence using 2′7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), a peroxide-selective probe [43]. The results showed that rotenone induced a robust level of H2O2 (in green) in the cells (Figure S4), in consistence with our recent findings [14]. Interestingly, rotenone-induced H2O2 overproduction was profoundly attenuated by BAPTA/AM (Figure S4) or EGTA (data not shown) in the cells. Quantitative analyses of the fluorescence intensities of H2O2 generation inhibited by BAPTA/AM or EGTA are shown in Figure 5A and 5B. Similarly, pretreatment with CaMKII inhibitor KN93 also markedly diminished rotenone induction of H2O2 in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Figure 5C), implying that CaMKII is involved in rotenone-induced H2O2 generation in neuronal cells. This was further confirmed by the observation that silencing CaMKII obviously reduced rotenone-triggered H2O2 overproduction in PC12 cells (Figure 5D). These data strongly suggest that rotenone evokes Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent induction of H2O2 overproduction, leading to apoptosis in neuronal cells.

Figure 5. Rotenone evokes Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent induction of H2O2 overproduction in neuronal cells.

PC12 cells and primary neurons, or PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII or GFP (as control), were treated with rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h, or pretreated with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM), EGTA (100 μM) or KN93 (10 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to rotenone (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h, followed by intracellular H2O2 imaging using a peroxide-selective probe H2DCFDA. A.-D. H2O2 imaging was quantified, showing that BAPTA/AM (A), EGTA (B), KN93 (C) or downregulation of CaMKII (D) dramatically attenuated rotenone-induced H2O2 generation in the cells, respectively. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). aP < 0.05, difference with control group; bP < 0.05, difference with 0.5 μM rotenone group; cP < 0.05, difference with 1 μM rotenone group; dP < 0.05, CaMKII shRNA group versus GFP shRNA group.

Rotenone also induces mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation activating CaMKII, leading to inhibition of mTOR pathway and neuronal apoptosis

Mitochondria are crucially involved in cellular Ca2+ and redox homeostasis and apoptosis induction [20, 44]. Because rotenone neurotoxicity is related to overproduction of mitochondrial ROS/H2O2 and disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis [14, 45], we next examined the association of rotenone-induced mitochondrial H2O2 generation with [Ca2+]i elevation in neuronal cells. In line with our recent findings [14], when PC12 cells and primary neurons were treated with rotenone (1 μM) in the presence or absence of thenoyltrifluoroacetone (TTFA, 10 μM), a mitochondrial complex II ubiquinone site inhibitor, which blocks electron supply to ubiquinol and consequential limiting the formation of ubisemiquinone [46], for 24 h, we observed an obvious decline in H2O2 fluorescence during co-treatment with rotenone and TTFA in the cells (Figure 6A). In contrast, when cells were exposed to rotenone in the presence of antimycin A (50 μM), a mitochondrial complex III inhibitor, which increases the lifetime of ubisemiquinone [47], for 24 h, we noticed a further increase in H2O2 level in the cells (Figure 6A). Of note, treatment with TTFA also elicited a significant reduction of [Ca2+]i, yet antimycin A resulted in an enhancement of [Ca2+]i triggered by rotenone (Figure 6B), implying that there exists mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation in neuronal cells in response to rotenone.

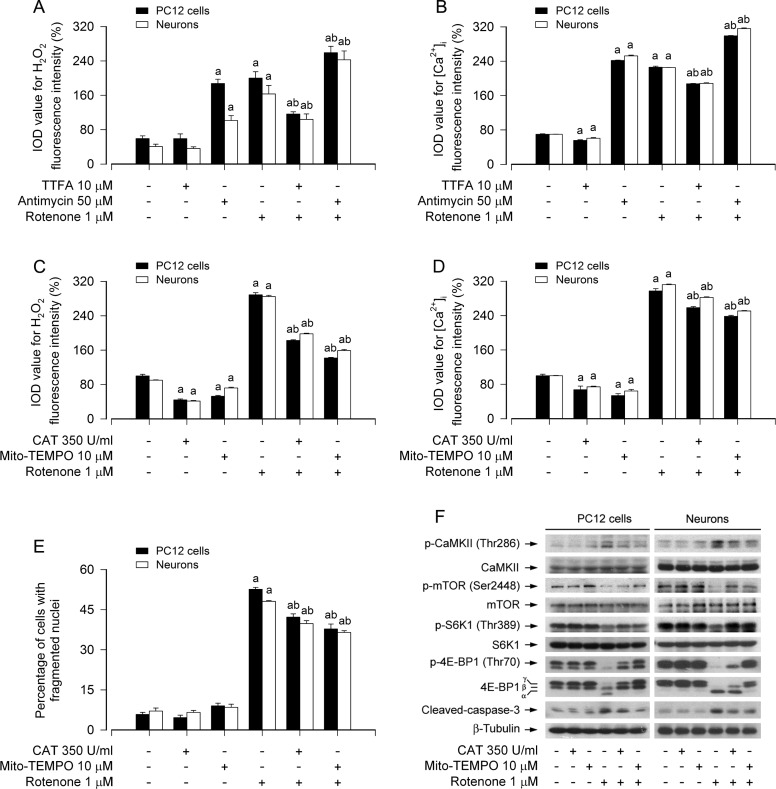

Figure 6. Rotenone induces mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation activating CaMKII, leading to inhibition of mTOR pathway and neuronal apoptosis.

PC12 cells and primary neurons were treated with rotenone (1 μM) in the presence or absence of TTFA (10 μM) or antimycin A (50 μM) for 24 h, or pretreated with/without CAT (350 U/ml) or Mito-TEMPO (10 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to rotenone (1 μM) for 24 h. Fluorescence intensity for cell H2O2 (A, C). and [Ca2+]i (B, D) was imaged and quantified using a peroxide-selective probe H2DCFDA and an intracellular Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-3/AM, respectively. Cell apoptosis was assayed using DAPI staining (E). Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies (F). The blots were probed for β-tubulin as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. A. There existed an obvious decline in H2O2 fluorescence during co-treatment with rotenone and TTFA in the cells, whereas a further increase in H2O2 level in the cells exposed to rotenone in the presence of antimycin A. B. Administration of TTFA elicited a significant reduction of [Ca2+]i, yet antimycin A resulted in an enhancement of [Ca2+]i triggered by rotenone. C.-E. Pretreatment with CAT or Mito-TEMPO significantly reduced intracellular H2O2 and [Ca2+]i levels (C, D) and prevented apoptosis in the cells induced by rotenone (E). F. Pretreatment with CAT or Mito-TEMPO substantially attenuated rotenone-induced activation of CaMKII phosphorylation, inhibition of mTOR, S6K1/4E-BP1 phosphorylation, and cleaved-caspase-3 in the cells. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). aP < 0.05, difference with control group; bP < 0.05, difference with 0.5 μM rotenone group; cP < 0.05, difference with 1 μM rotenone group.

To gain more insights into the event that rotenone induces mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation leading to neuronal apoptosis, we extended our studies using catalase (CAT), a H2O2-scavenging enzyme, and Mito-TEMPO, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant [48]. Pretreatment with CAT (350 U/ml) or Mito-TEMPO (10 μM) significantly reduced rotenone-induced H2O2 and [Ca2+]i (Figure 6C and 6D), and prevented rotenone-induced apoptosis (Figure 6E) in PC12 cells and primary neurons. Consistently, CAT or Mito-TEMPO also diminished rotenone-induced cleavage of caspase-3 in the cells (Figure 6F). Furthermore, we found that pretreatment with CAT or Mito-TEMPO substantially attenuated rotenone-induced activation of CaMKII phosphorylation and inhibition of mTOR, S6K1/4E-BP1 phosphorylation in the cells (Figure 6F). Collectively, our findings demonstrate that rotenone induces mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation, which activates CaMKII, leading to inhibition of mTOR pathway and consequential neuronal apoptosis.

Ectopic expression of wild-type mTOR or constitutively active S6K1, or downregulation of 4E-BP1 partially prevents rotenone elevation of [Ca2+]i-mediated CaMKII phosphorylation and neuronal apoptosis

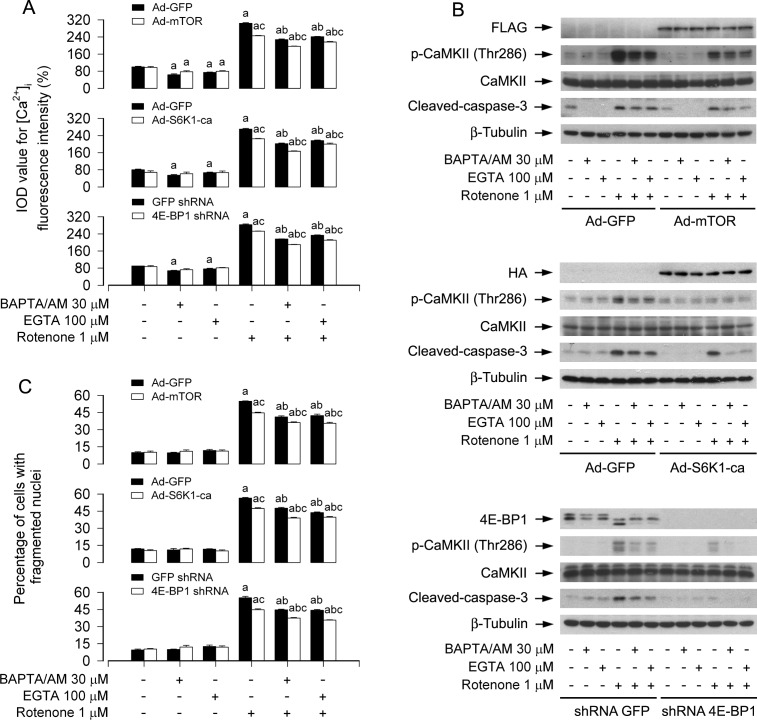

Recently we have found that ectopic expression of wild-type mTOR (mTOR-wt) or constitutively active S6K1 (S6K1-ca), or downregulation of 4E-BP1 partially prevented rotenone-induced H2O2 and apoptosis in neuronal cells [14]. This prompted us to postulate that expression of mTOR-wt, S6K1-ca, or silencing 4E-BP1 may prevent rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting mitochondrial H2O2 and blocking Ca2+ signaling. To test this concept, PC12 cells were infected with Ad-mTOR, Ad-S6K1-ca or Ad-GFP (as control), or with lentiviral shRNA to 4E-BP1 or GFP, and then exposed to rotenone (1 μM) for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without CAT (350 U/ml), Mito-TEMPO (10 μM), BAPTA/AM (30 μM) or EGTA (100 μM) for 1 h, respectively. As expected, expression of mTOR-wt or S6K1-ca, or silencing 4E-BP1 substantially blocked rotenone-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i (Figure 7A and Figure S5A), phosphorylation of CaMKII (Figure 7B and Figure S5B), respectively. Consistently, rotenone-induced cleavage of caspase-3 was apparently attenuated by expression of mTOR-wt or S6K1-ca, or silencing 4E-BP1 (Figure 7B and Figure S5B). Furthermore, expression of mTOR-wt or S6K1-ca, or silencing 4E-BP1 also partially rescued PC12 cells from apoptosis induced by rotenone (Figure 7C and Figure S5C). Of importance, addition of CAT, Mito-TEMPO, BAPTA/AM or EGTA exhibited more inhibitory effects on rotenone-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII, inhibition of mTOR pathway, and induction of apoptosis in the cells infected with Ad-mTOR, Ad-S6K1-ca, or 4E-BP1 lentiviral shRNA than in Ad-GFP or GFP shRNA control group (Figure 7A-7C and Figure S5A-C). Collectively, our findings suggest that rotenone elevation of mitochondrial H2O2- and [Ca2+]i-mediated CaMKII phosphorylation inhibits mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways, leading to neuronal apoptosis; activation of mTOR pathway, in turn, can partially prevent rotenone from increasing mitochondrial H2O2 and [Ca2+]i, thereby attenuating rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis.

Figure 7. Ectopic expression of wild-type mTOR or constitutively active S6K1, or downregulation of 4E-BP1 reinforces BAPTA/AM's or EGTA's prevention of rotenone elevation of [Ca2+]i-mediated CaMKII phosphorylation and neuronal apoptosis.

PC12 cells infected with Ad-mTOR, Ad-S6K1-ca or Ad-GFP, or PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to 4E-BP1 or GFP, respectively, were pretreated with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM) or EGTA (100 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to rotenone (1 μM) for 24 h. [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensity was imaged and quantified using an intracellular Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-3/AM (A). Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies (B). The blots were probed for β-tubulin as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Cell apoptosis was assayed using DAPI staining (C). A.-C. Ectopic expression of wild-type mTOR or constitutively active S6K1, or silencing 4E-BP1 enhanced BAPTA/AM's or EGTA's prevention of rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation (A), CaMKII phosphorylation and cleaved-caspase-3 (B), as well as neuronal apoptosis (C). Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). aP < 0.05, difference vs control group; bP < 0.05, difference with 1 μM rotenone group; cP < 0.05, Ad-mTOR group or Ad-S6K1-ca group versus Ad-GFP group, or 4E-BP1 shRNA group versus GFP shRNA group.

DISCUSSION

Ca2+ signaling is an important component of signal transduction pathways, which regulates a variety of physiological responses of neurons to neurotransmitters and neurotrophic factors, including cell survival responses [16, 49]. Several previous studies have shown that disturbances in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis trigger synaptic dysfunction, impaired plasticity, and neuronal degeneration such as PD, AD and HD [16-19]. Especially, prolonged change in Ca2+ distribution in cells elicits a set of biochemical cascades that lead to apoptosis [20, 21]. Rotenone, a broad-spectrum pesticide, has been reported to disrupt [Ca2+]i homeostasis or induce [Ca2+]i elevation, leading to apoptosis in neuronal cells, such as nigral dopaminergic neurons [45] and Neuro-2a cells [37]. Our group has recently demonstrated that rotenone inhibits mTOR-mediated S6K and 4E-BP1 pathways leading to neuronal apoptosis [14, 36]. However, it is not clear whether rotenone inhibits mTOR signaling in Ca2+ dependent manner. Here, we provide evidence that pretreatment with BAPTA/AM (an intracellular Ca2+ chelator) or EGTA (an extracellular Ca2+ chelator) significantly attenuated rotenone-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i level, inhibition of mTOR pathway, and induction of apoptosis in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Figure 2A-2F). The findings indicate that rotenone inhibition of mTOR pathway, leading to neuronal apoptosis, is attributed to [Ca2+]i elevation, which, at least, involves extracellular Ca2+ influx, in neuronal cells in response to rotenone.

CaMKII, a ubiquitously expressed multifunctional Ser/Thr kinase, regulates the survival of neuronal cells [33, 50-52]. It is activated upon binding of Ca2+/CaM complex [41, 42]. As CaMKII is a general integrator of Ca2+ signaling, we speculated that rotenone might inhibit mTOR pathway and induce neuronal apoptosis by elevating Ca2+-dependent CaMKII phosphorylation. In this study, we found that 24-h exposure to rotenone increased CaMKII phosphorylation concentration-dependently in PC12 cells and primary neurons. Chelating intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA/AM obviously inhibited rotenone-induced CaMKII phosphorylation in the cells, suggesting a [Ca2+]i-dependent mechanism. To unveil whether CaMKII activity is essential for rotenone-induced inhibition of mTOR signaling contributing to neuronal apoptosis, KN93, a specific inhibitor of CaMKII [53], was used. We found that KN93 significantly blocked rotenone-induced CaMKII phosphorylation, and effectively prevented rotenone from inhibiting mTOR pathway and inducing apoptosis in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Figure 4A and 4B). Similar results were observed in the cells treated with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII (Figure 4C-4E). These findings strongly support that CaMKII plays a bridging role between rotenone-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i and inhibition of mTOR pathway, leading to neuronal apoptosis.

Mitochondria play a crucial role in cellular Ca2+ and redox homeostasis and apoptosis induction [20, 44]. In the mitochondria, the respiratory chain complexes I and III are the primary mitochondrial sources of univalent reduction of O2 into superoxide (O2-•) [20, 54]. Both SOD1 and SOD2 can catalyze the dismutation of O2-• into O2 and H2O2 [55]. Of note, H2O2 takes place mainly at the most vulnerable mitochondrial complex I [43]. For example, H2O2 in mitochondria in situ in isolated nerve terminals is sufficiently enhanced when mitochondrial complex I is inhibited at a small degree [9]. Rotenone elicits mitochondrial ROS/H2O2-dependent neuronal apoptosis via inhibiting mitochondrial complex I [3, 4, 14]. In the present study, we identified that rotenone evokes Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent induction of H2O2 overproduction in the mitochondria of neuronal cells. This is supported by the findings that pretreatment with BAPTA/AM, EGTA or KN93, or silencing CaMKII markedly reduced H2O2 overproduction of neuronal cells in response to rotenone (Figure S4 and Figure 5). Furthermore, TTFA (a mitochondria complex II inhibitor) or Mito-TEMPO (a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant) blocked rotenone-induced mitochondrial H2O2 production, preventing [Ca2+]i elevation/CaMKII phosphorylation, mTOR inhibition and neuronal apoptosis (Figure 6). Collectively, the above findings suggest that rotenone induces mitochondrial H2O2, resulting in elevation of [Ca2+]i, and rotenone, in turn, evokes Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent overproduction of H2O2 in neuronal cells, inhibiting mTOR signaling and inducing neuronal apoptosis. Thus, there exists a crosstalk between Ca2+ signaling and mitochondrial H2O2, which is required for rotenone inhibition of mTOR signaling and induction of neuronal cell death.

In this study, we also noticed that expression of mTOR-wt or S6K1-ca, or silencing 4E-BP1 attenuated rotenone-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i, phosphorylation of CaMKII, and neuronal apoptosis (Figure 7 and Figure S5). The results suggest that on one hand, rotenone induces [Ca2+]i and mitochondrial H2O2, resulting in elevation of inhibition of mTOR, and induction of neuronal apoptosis; on the other hand, activation of mTOR pathway can, in turn, partially prevent rotenone from increasing [Ca2+]i and mitochondrial H2O2 and thus attenuating rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis. Currently we have no clue regarding how mTOR regulates [Ca2+]i and mitochondrial H2O2 in the cells in response to rotenone.

It has been known that many cell death stimuli alter the level of Ca2+ in the cytosol and the storage of Ca2+ in the intracellular organelles [33, 56]. [Ca2+]i increase is usually triggered by Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores and/or Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space [15]. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is one of the major Ca2+ storage units in cells, and blockers of ER calcium channel, such as IP3 receptors, can effectively prevent Ca2+ release induced by various stimuli [15, 20]. The mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM), a structure for association of the mitochondria with the ER membrane, can integrate signal transduction pathways to regulate the communication and functional interactions between the ER and mitochondrion, especially in Ca2+ exchanges [20, 57]. Under pathological conditions, Ca2+ exchange between mitochondria and ER mediated by MAM is an important apoptotic control point [20]. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether rotenone disrupts Ca2+ homeostasis in the neuronal cells by increasing [Ca2+]i elevation and/or decreasing [Ca2+]i clearance. Understanding the underlying mechanisms may be helpful to uncover why overexpression of mTOR-wt or S6K1-ca or downregulation of 4E-BP1 suppresses rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation.

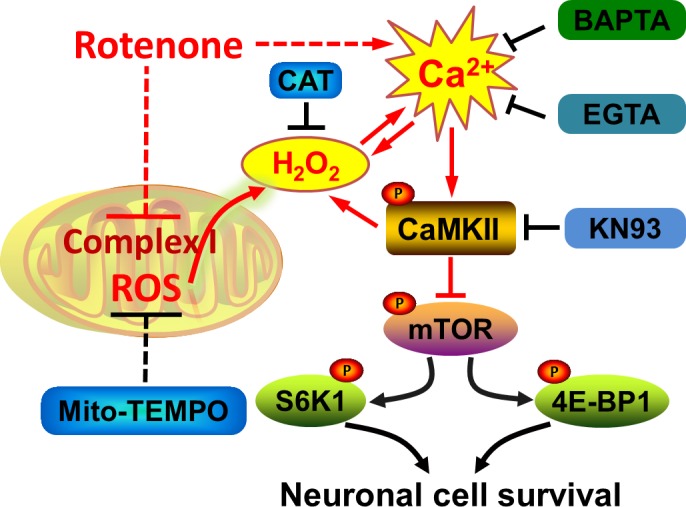

In summary, we have identified that rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation inhibits mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways contributing to neuronal apoptosis, through stimulating phosphorylation of CaMKII. Rotenone-induced extracellular Ca2+ influx at least plays an important role in contributing to neuronal apoptosis. Rotenone elicits Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent H2O2 overproduction, and reversely rotenone also induces mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation activating CaMKII, thereby inhibiting mTOR signaling and reducing neuronal cell survival (i.e. inducing apoptosis) (Figure 8). Our findings highlight that the crosstalk between Ca2+ signaling and mitochondrial H2O2 is required for rotenone inhibition of mTOR pathway leading to neuronal apoptosis. The findings suggest that how to control over-elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and overproduction of mitochondrial H2O2 may be a new strategy to fight against the neurotoxicity of rotenone.

Figure 8. A schematic diagram showing how rotenone induces apoptosis by Ca2+/H2O2-dependent inhibition of mTOR pathway.

Rotenone-induced [Ca2+]i elevation activates CaMKII, resulting in inhibition of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways, which are crucial for cell survival. Rotenone elicits Ca2+-CaMKII-dependent H2O2 overproduction, and reversely rotenone also induces mitochondrial H2O2-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation activating CaMKII, thereby inhibiting mTOR signaling and inducing neuronal apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Rotenone, CAT, poly-D-lysine (PDL), H2DCFDA, 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF), protease inhibitor cocktail, TTFA, antimycin A, and DAPI, and EGTA were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA, NEUROBASALTM Media, and B27 Supplement were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). Horse serum and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were supplied by Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence solution was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit was from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). BAPTA/AM was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Mito-TEMPO and KN93 were acquired from ALEXIS Biochemicals Corporation (San Diego, CA, USA). The following antibodies were used: phospho-CaMKII (Thr286), phospho-S6K1 (Thr389), phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr70), 4E-BP1, cleaved-caspase-3, PARP (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); S6K1, CaMKII (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); β-tubulin, phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR, HA, FLAG (Sigma); Goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, and rabbit anti-goat IgG-HRP (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Other chemicals were purchased from local commercial sources and were of analytical grade.

Cell lines, primary neurons and cultures

Rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) was maintained in antibiotic-free DMEM supplemented with 10% horse serum and 5% FBS at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. Primary cortical neurons were isolated from fetal mice at 16-18 days of gestation and cultured as described previously [35].

Recombinant adenoviral constructs and infection of cells

The recombinant adenoviruses encoding N-terminal FLAG-tagged wild-type mTOR (Ad-mTOR-wt), HA-tagged constitutively active S6K1 (Ad-S6K1-ca), and the control virus encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Ad-GFP) were generated as described previously [35, 58]. The viruses were amplified, titrated and used as described [59].

Lentiviral shRNA cloning, production, and infection

Lentiviral shRNAs to 4E-BP1, CaMKII and GFP (as control) were generated and used as described [33, 35]. For use, monolayer PC12 cells, when grown to about 70% confluence, were infected with above lentivirus-containing supernatant in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene and exposed to 2 μg/ml puromycin after 24 h of infection. In 5 days, cells were used for experiments.

Analysis for cell viability

PC12 cells and primary neurons, seeded in a 96-well plate (1 × 104 cells/well) pre-coated with PDL (0.2 μg/ml for PC12 cells; 10 μg/ml for primary neurons), were treated with 0-1 μM rotenone for 24 h, or with/without 0.5 and 1 μM rotenone for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM), EGTA (100 μM), or KN93 (10 μM) for 1 h, with 5 replicates of each treatment. In some cases, PC12 cells, infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII or GFP, respectively, were seeded in a 96-well plate (1 × 104 cells/well). Next day, cells were exposed to 0.5 and 1 μM rotenone for 24 h. Subsequently, cell viability, after incubation with MTS reagent (one solution reagent) (20 μl/well) for 3 h, was evaluated by measuring the optical density (OD) at 490 nm using a SynergyTM 2 Multi-function Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc. Winooski, Vermont, USA).

DAPI and TUNEL staining

PC12 cells and primary neurons, PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII, 4E-BP1 or GFP, or PC12 cells infected with Ad-mTOR, Ad-S6K1-ca or Ad-GFP, respectively, were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/well in a 6-well plate containing a PDL-coated glass coverslip per well, Next day, cells were treated with 0-1 μM rotenone for 24 h, or with/without 0.5 and/or 1 μM rotenone for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM), EGTA (100 μM), KN93 (10 μM), CAT (350 U/ml) or Mito-TEMPO (10 μM) for 1 h, with 5 replicates of each treatment. Subsequently, the cells with fragmented and condensed nuclei were stained by adding DAPI (4 μg/ml in deionized water) as described [60]. Photographs for cell apoptosis were taken under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon 80i, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera. In addition, for PC12 cells and primary neurons treated with 0-1 μM rotenone for 24 h, after DAPI staining, the following staining was performed by adding TUNEL reaction mixture (TdT enzyme solution and labeling solution) according to the manufacture's instructions of In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit® (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Finally, photographs were taken under a fluorescence microscope with a digital camera. For quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity using TUNEL staining, the integral optical density (IOD) was measured by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., Newburyport, MA, USA).

Analysis for [Ca2+]i imaging

PC12 cells and primary neurons, PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to 4E-BP1 or GFP, or PC12 cells infected with Ad-mTOR, Ad-S6K1-ca or Ad-GFP, respectively, were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/well in a 6-well plate containing a PDL-coated glass coverslip per well. Next day, cells were treated with 0-1 M rotenone for 24 h, with/without 1 μM rotenone in the presence or absence of TTFA (10 μM) or antimycin A (50 μM) for 24 h, or with/without 0.5 and/or 1 μM rotenone for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM), EGTA (100 μM), CAT (350 U/ml) or Mito-TEMPO (10 μM) for 1 h. The cells were then loaded with 5 μM Fluo-3/AM for 40 min. Finally, all stained coverslips were rinsed twice with PBS, followed by imaging under a fluorescence microscope. IOD for quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity was analyzed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software as described above.

Cell H2O2 imaging

Imaging intracellular H2O2 was recorded by using a nonfluorescent probe, H2DCFDA. This peroxide-selective dye can penetrate into the intracellular matrix of cells, where it is cleaved by intracellular esterases and oxidized by H2O2 to form fluorescent DCF [43]. In brief, PC12 and primary neurons, or PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII or GFP, were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well plate containing a glass coverslip per well. Next day, cells were treated with 0, 0.5, 1 μM rotenone for 24 h, or with/without 1 μM rotenone in the presence or absence of TTFA (10 μM) or antimycin A (50 μM) for 24 h, or with/without 0.5 and/or 1 μM rotenone for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM), EGTA (100 μM), KN93 (10 μM), CAT (350 U/ml) or Mito-TEMPO (10 μM) for 1 h. The cells were then loaded with H2DCFDA (20 μM) for 1 h. Lastly, all stained coverslips were rinsed three times with PBS, followed by imaging under a fluorescence microscope. For quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity, IOD was measured by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software as described above.

Western blot analysis

PC12 cells and primary neurons, or PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII, 4E-BP1 or GFP, or PC12 cells infected with Ad-mTOR, Ad-S6K1-ca or Ad-GFP, respectively, were treated with 0-1 μM rotenone for 24 h, or with/without 0.5 and/or 1 μM rotenone for 24 h following pre-incubation with/without BAPTA/AM (30 μM), EGTA (100 μM), KN93 (10 μM), CAT (350 U/ml) or Mito-TEMPO (10 μM) for 1 h. Afterwards, Western blotting was performed as described [35].

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard error (mean ± SE). Student's t-test for non-paired replicates was used to identify statistically significant differences between treatment means. Group variability and interaction were compared using either one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-tests to compare replicate means. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL FIGURES

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271416; L.C.), Project for the Priority Academic Program Development and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (10KJA180027; L.C.), NIH (CA115414; S.H.), American Cancer Society (RSG-08-135-01-CNE; S.H.), Louisiana Board of Regents (NSF-2009-PFUND-144; S.H.), and Innovative Research Program of Jiangsu College Graduate of China (KYLX15_0733; C.L.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blesa J, Phani S, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S. Classic and new animal models of Parkinson's disease. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:845618. doi: 10.1155/2012/845618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drechsel DA, Patel M. Role of reactive oxygen species in the neurotoxicity of environmental agents implicated in Parkinson's disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1873–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taetzsch T, Block ML. Pesticides, microglial NOX2, and Parkinson's disease. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2013;27:137–149. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li N, Ragheb K, Lawler G, Sturgis J, Rajwa B, Melendez JA, Robinson JP. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone induces apoptosis through enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8516–8525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swarnkar S, Singh S, Mathur R, Patro IK, Nath C. A study to correlate rotenone induced biochemical changes and cerebral damage in brain areas with neuromuscular coordination in rats. Toxicology. 2010;272:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tretter L, Sipos I, Adam-Vizi V. Initiation of neuronal damage by complex I deficiency and oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:569–577. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000014827.94562.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamilselvam K, Braidy N, Manivasagam T, Essa MM, Prasad NR, Karthikeyan S, Thenmozhi AJ, Selvaraju S, Guillemin GJ. Neuroprotective effects of hesperidin, a plant flavanone, on rotenone-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in a cellular model for Parkinson's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:102741. doi: 10.1155/2013/102741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adam-Vizi V. Production of reactive oxygen species in brain mitochondria: contribution by electron transport chain and non-electron transport chain sources. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1140–1149. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Rocha H, Garcia-Garcia A, Pickett C, Li S, Jones J, Chen H, Webb B, Choi J, Zhou Y, Zimmerman MC, Franco R. Compartmentalized oxidative stress in dopaminergic cell death induced by pesticides and complex I inhibitors: Distinct roles of superoxide anion and superoxide dismutases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;61:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong N, Long X, Xiong J, Jia M, Chen C, Huang J, Ghoorah D, Kong X, Lin Z, Wang T. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone-induced toxicity and its potential mechanisms in Parkinson's disease models. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2012;42:613–632. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.680431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannon JR, Tapias V, Na HM, Honick AS, Drolet RE, Greenamyre JT. A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao HM, Hong JS, Zhang W, Liu B. Synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity of the pesticide rotenone and inflammogen lipopolysaccharide: relevance to the etiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1228–1236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Q, Liu C, Liu W, Zhang H, Zhang R, Liu J, Zhang J, Xu C, Liu L, Huang S, Chen L. Rotenone induction of hydrogen peroxide inhibits mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1/eIF4E pathways, leading to neuronal apoptosis. Toxicol Sci. 2015;143:81–96. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattson MP. Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell. 2007;6:337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons SJ, Brorson JR, Bleakman D, Chard PS, Miller RJ. Calcium influx and neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;679:22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toescu EC, Verkhratsky A. Role of calcium in normal aging and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell. 2007;6:265. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marambaud P, Dreses-Werringloer U, Vingtdeux V. Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng G, Kong RH, Zhang LM, Zhang JN. Mitochondria in traumatic brain injury and mitochondrial-targeted multipotential therapeutic strategies. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:699–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajnoczky G, Davies E, Madesh M. Calcium signaling and apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunter TE, Sheu SS. Characteristics and possible functions of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:1291–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS, Jin Y, Lemasters JJ. Reactive oxygen species, but not Ca2+ overloading, trigger pH- and mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent death of adult rat myocytes after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:2024–2034. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00683.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franklin JL. Redox regulation of the intrinsic pathway in neuronal apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1437–1448. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niizuma K, Yoshioka H, Chen H, Kim GS, Jung JE, Katsu M, Okami N, Chan PH. Mitochondrial and apoptotic neuronal death signaling pathways in cerebral ischemia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller RL, James-Kracke M, Sun GY, Sun AY. Oxidative and inflammatory pathways in Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9656-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Circu ML, Aw TY. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swiech L, Perycz M, Malik A, Jaworski J. Role of mTOR in physiology and pathology of the nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaworski J, Sheng M. The growing role of mTOR in neuronal development and plasticity. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;34:205–219. doi: 10.1385/MN:34:3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu B, Chen S, Luo Y, Chen Z, Liu L, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Chen L, Huang S. Calcium signaling is involved in cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis via induction of reactive oxygen species and activation of MAPK/mTOR network. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen S, Ren Q, Zhang J, Ye Y, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Guo M, Ji H, Xu C, Gu C, Gao W, Huang S, Chen L. N-acetyl-L-cysteine protects against cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting ROS-dependent activation of Akt/mTOR pathway in mouse brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40:759–777. doi: 10.1111/nan.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S, Xu Y, Xu B, Guo M, Zhang Z, Liu L, Ma H, Chen Z, Luo Y, Huang S, Chen L. CaMKII is involved in cadmium activation of MAPK and mTOR pathways leading to neuronal cell death. J Neurochem. 2011;119:1108–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Kontos CD, Huang S. Cadmium induction of reactive oxygen species activates the mTOR pathway, leading to neuronal cell death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Yin J, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Huang S. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits mTOR signaling by activation of AMPKalpha leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells. Lab Invest. 2010;90:762–773. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, Liu C, Chen S, Ye Y, Guo M, Ren Q, Liu L, Zhang H, Xu C, Zhou Q, Huang S, Chen L. Activation of AMPK and inactivation of Akt result in suppression of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways leading to neuronal cell death in in vitro models of Parkinson's disease. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1680–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swarnkar S, Goswami P, Kamat PK, Gupta S, Patro IK, Singh S, Nath C. Rotenone-induced apoptosis and role of calcium: a study on Neuro-2a cells. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86:1387–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0853-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XJ, Xu JX. Possible involvement of Ca2+ signaling in rotenone-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett. 2005;376:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicotera P, Orrenius S. The role of calcium in apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hao B, Cheng S, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. Caspofungin kills Candida albicans by causing both cellular apoptosis and necrosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:326–332. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01366-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colbran RJ, Brown AM. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schworer CM, Colbran RJ, Soderling TR. Reversible generation of a Ca2+-independent form of Ca2+(calmodulin)-dependent protein kinase II by an autophosphorylation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8581–8584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bao L, Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. Partial mitochondrial inhibition causes striatal dopamine release suppression and medium spiny neuron depolarization via H2O2 elevation, not ATP depletion. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10029–10040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2652-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koopman WJ, Nijtmans LG, Dieteren CE, Roestenberg P, Valsecchi F, Smeitink JA, Willems PH. Mammalian mitochondrial complex I: biogenesis, regulation, and reactive oxygen species generation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1431–1470. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freestone PS, Chung KK, Guatteo E, Mercuri NB, Nicholson LF, Lipski J. Acute action of rotenone on nigral dopaminergic neurons--involvement of reactive oxygen species and disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1849–1859. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno-Sanchez R, Hernandez-Esquivel L, Rivero-Segura NA, Marin-Hernandez A, Neuzil J, Ralph SJ, Rodriguez-Enriquez S. Reactive oxygen species are generated by the respiratory complex II--evidence for lack of contribution of the reverse electron flow in complex I. FEBS J. 2013;280:927–938. doi: 10.1111/febs.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lanju X, Jing X, Shichang L, Zhuo Y. Induction of apoptosis by antimycin A in differentiated PC12 cell line. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;34:651–657. doi: 10.1002/jat.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeh YT, Yeh H, Su SH, Lin JS, Lee KJ, Shyu HW, Chen ZF, Huang SY, Su SJ. Phenethyl isothiocyanate induces DNA damage-associated G2/M arrest and subsequent apoptosis in oral cancer cells with varying p53 mutations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;74:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng A, Wang S, Yang D, Xiao R, Mattson MP. Calmodulin mediates brain-derived neurotrophic factor cell survival signaling upstream of Akt kinase in embryonic neocortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7591–7599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song B, Lai B, Zheng Z, Zhang Y, Luo J, Wang C, Chen Y, Woodgett JR, Li M. Inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3 by CaMKII couples depolarization to neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41122–41134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.130351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim BW, Choi M, Kim YS, Park H, Lee HR, Yun CO, Kim EJ, Choi JS, Kim S, Rhim H, Kaang BK, Son H. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling regulates hippocampal neurons by elevation of intracellular calcium and activation of calcium/calmodulin protein kinase II and mammalian target of rapamycin. Cell Signal. 2008;20:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamanaka A, Hiragami Y, Maeda N, Toku S, Kawahara M, Naito Y, Yamamoto H. Involvement of CaM kinase II in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced activation of MAP kinase in cultured hypothalamic neurons. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;466:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi SS, Seo YJ, Shim EJ, Kwon MS, Lee JY, Ham YO, Suh HW. Involvement of phosphorylated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein in the mouse formalin pain model. Brain Res. 2006;1108:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mustafa AG, Singh IN, Wang J, Carrico KM, Hall ED. Mitochondrial protection after traumatic brain injury by scavenging lipid peroxyl radicals. J Neurochem. 2010;114:271–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez M, Negro S, Slowing K, Fernandez-Carballido A, Barcia E. An effective novel delivery strategy of rasagiline for Parkinson's disease. Int J Pharm. 2011;419:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bian X, Hughes FM, Jr, Huang Y, Cidlowski JA, Putney JW., Jr Roles of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and intracellular Ca2+ stores in induction and suppression of apoptosis in S49 cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:1241–1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pizzo P, Pozzan T. Mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum choreography: structure and signaling dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu L, Li F, Cardelli JA, Martin KA, Blenis J, Huang S. Rapamycin inhibits cell motility by suppression of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways. Oncogene. 2006;25:7029–7040. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu L, Chen L, Chung J, Huang S. Rapamycin inhibits F-actin reorganization and phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins. Oncogene. 2008;27:4998–5010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen L, Liu L, Luo Y, Huang S. MAPK and mTOR pathways are involved in cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2008;105:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.