Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an intriguing clinical entity. Its clinical connotations are varied, the updates of which are required to be done periodically. An attempt to bring its various facets have been made highlighting its clinical features keeping in view the major and the minor criteria to facilitate the diagnosis, differential diagnosis, complications, and associated dermatoses. The benefit of the current dissertation may percolate to the trainees in dermatology, in addition to revelations that atopic undertones in genetic susceptibility and metabolic disorder may provide substantive insight for the future in the understanding of thus far enigmatic etiopathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, clinical connotation, genetic susceptibility, metabolic disorder

What was known?

Atopic dermatitis, a well-conceived age related entity pre-eminently identified through infantile, childhood and adult phases. Senile atopic dermatitis characterized by marked xerosis and conspicuous absence of lichenification.

Introduction

Symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD) usually start in infancy. Intense pruritus and cutaneous reactivity are its presenting features. It can present with three clinical patterns. Acute atopic eczema presents with a weeping, crusting papulovesicular eruption. Subacute AD presents with dry and scaly erythematous papules and plaques.[1] Features of lichenification and fibrotic papules may be apparent in chronic cases.[2,3,4,5,6] it is, therefore, interesting to dwell on concomitant atopic undertones in predisposed genetic and metabolic disorders, the salient glimpses of which are succinctly depicted. It may be enlightening for comprehending the etiopathogenesis[7,8] of AD in perspective.

Clinical Connotation

Age-related clinical features are fairly representative and assist in the diagnosis of AD, the outline of which is defined below:

Infantile phase

This phase refers to the disease in the first 2 years of life. Its onset is within the first 6 months. The lesions usually begin on the face and scalp [Figures 1–3]. They are symmetric and gradually spread to other parts, especially extensors of limbs as infants start to crawl. However, the distribution characteristics may vary. In an Indian study, 79% in the infantile AD group had facial involvement, 52.3% had extensor involvement, 42% had flexors affected, and 5.7% had both flexors and extensors affected.[9]

Figure 1.

Atopic dermatitis: erythematous-squamous plaques over posterior aspect of thighs in a 3-year-old boy

Figure 3.

Atopic dermatitis: Erythematous, scaly and partially crusted papules and plaques in a 7-month-old infant

Figure 2.

Atopic dermatitis: depicting erythemato-squamous plaque affecting the cheeks and forehead in a 1-year-old boy

Acute, oozing eczematous, crusting and impetiginization are also seen. It may run a chronic relapsing course.

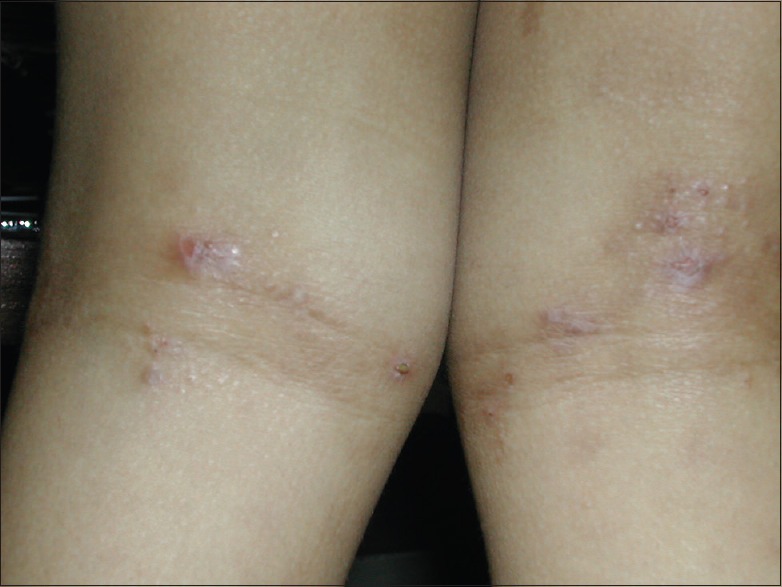

Childhood phase

This phase starts from 2 to 12 years of age. Frequently, involved sites are flexures of the elbow/knee and wrist. Ankle and neck may also be affected [Figure 4]. Subacute to chronic lichenified dermatitis is frequent.[6]

Figure 4.

Atopic dermatitis: Erythematous and scaly plaques over forehead and cheeks in a 2-year-old boy

In the study quoted above, in the childhood group, 74.5% of children had facial involvement, 35.5% had flexures affected, 56.32% had extensor involvement, and 8.24% had both flexors and extensors affected.[8]

Adolescent phase

The disease course between 12 and 18 years is characterized by lichenified eczematous lesions, primarily affecting the flexures [Figures 5 and 6]. Classic eczematous and typical lichenoid may be seen in this age group.[10]

Figure 5.

Atopic dermatitis: Scaly and lichenified plaques over thighs with extension to the popliteal fossae in a 4-year-old child

Figure 6.

Atopic dermatitis: Excoriated papules with lichenification in the popliteal fossa

Adult type

After 18 years of age, lichenified lesions are more common, and can be seen especially on flexures and hands. Localized, isolated lesions can also be seen.[5]

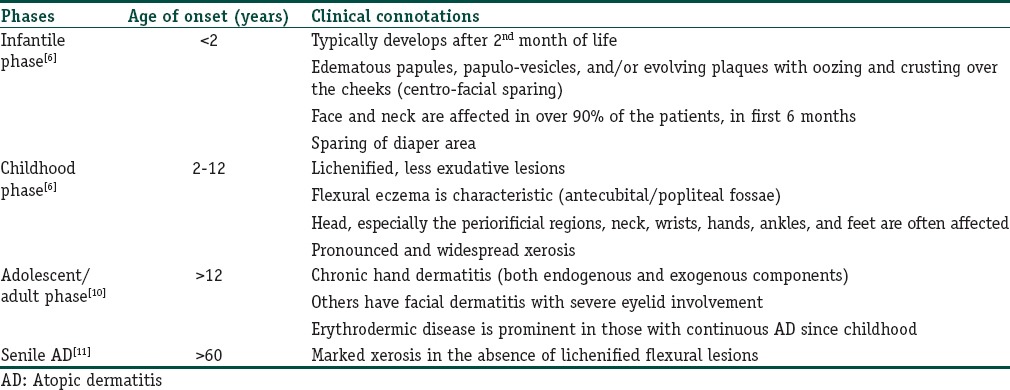

Aforementioned phases of AD are succinctly displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Atopic dermatitis: Displaying age-related clinical connotations

Localized variations, namely nipple eczema, eyelid eczema, cheiltis, vulval eczema, infra-auricular, and infra-nasal fissuring may also be seen in adults and adolescents. Morphological variants like follicular, pityriasis alba-like, papular – lichenoid, nummular/discoid, prurigo-like, dyshidrotic, and erythrodermic forms may be recognized in isolated cases.[4,5] Hyper-linearity of palms and soles, Dennie–Morgan infraorbital fold, white dermographism, facial pallor, low hairline, and keratosis pilaris are a few other associations. Dermatitis of hands and feet is also commonly seen. In more severe cases, thick lichenified plaques are seen on the dorsal hands, feet, and knees. Children with darker skin typically have perifollicular hyperpigmented or hypopigmented rough 1–2-mm papules that can coalesce into broad, near-diffuse plaques, most prominent on the extensor surfaces.

Xerosis or icthyosis of the surrounding skin is common. Postinflammatory pigmentary changes (hyper/hypo) are also commonly seen at sites of previously healed lesions. Excoriations and erosions are nearly universal and are often the result of scratching or an indication of bacterial colonization.

Aggravation of dermatitis may occur with a variety of factors such as climate, sweating, intercurrent infections, irritants, food allergy, and psychosomatic undertones. Aero-allergens such as animal dander may also provoke an attack.[4,5,12,13,14]

While majority of the patients in one study had aggravation of their eczema in the winters (62%) as a result of decreased moisture in the climate, 17% had aggravation in the summers probably due to hyperhidrosis, itching and secondary skin infections[15] Similar was the findings of Dhar and Kanwar: 67.14% of infants had aggravation during winters, and 23.36% had aggravation during summers.[9] The corresponding figures in the childhood AD patients were 58% and 32.9%, respectively.[9] On the contrary, in the study by Dhar and Kanwar in different climatic conditions in Eastern India, 40% patients had aggravation during summers, and only 15% had winter exacerbation.[16]

Complications

Respiratory allergy

Several studies have evaluated the association between AD and respiratory allergy, Kulig et al.[17] have shown that, at the age of 5 years, 50% of children with AD have developed allergic respiratory diseases. van der Hulst et al.[18] in their systematic review have confirmed that young children with AD had a high risk of developing asthma in later childhood. According to a recent study by Spergel,[19] more than 50% of children with AD may develop asthma and approximately 75% allergic rhinitis during the first 6 years of life.

Retarded growth

Even before the advent of effective corticosteroid therapy, a retarded growth was reported,[20] which may, in present times, be exacerbated by treatment with oral and/or topical steroids.

A longitudinal study[21] to look for the effect of AD on growth was carried out. The growth patterns of 62 children aged 3–5 years, suffering from AD were studied in terms of body weight, height, and head circumference. Sixty-eight normal healthy children matched for age, sex, and socioeconomic status were taken as controls. The growth velocities were lower in patients with AD than in controls. The mean values for height and head circumference were found to be significantly lower in girls than in the girls of the control group whereas, in boys, these values for the patients remained comparable or higher than in the boys of the control group at some of the ages. Growth retardation was observed among children with a more severe form of the disease. Height of the affected children was mostly compromised.

Bacterial infections

Secondary bacterial infections by Streptococcus or Staphylococcus have often been encountered in the patients, especially those on topical and/or oral corticosteroids.[20] Secondarily infected AD presents with pustules and crusting. It should be suspected when lesions do not respond to conventional treatment or if fever and malaise are present alongside.[1]

Viral infections

Both in active and quiescent stages, these patients can develop acute generalized herpes simplex (eczema herpeticum), and vaccinia (eczema vaccinatum). Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome may aggravate the condition.[20]

Ocular abnormalities

Apart from Dennie–Morgan fold, eyes reveal conjunctival inflammation and keratoconjunctivitis. Keratoconus may be an infrequent accompaniment. Cataract may occur in up to 10% of severe adolescent/adult cases.[20]

A recent study[22] has investigated ocular abnormalities in 100 Indian patients, in the age group of 1–14 years, and reported ocular changes in the form of lid and conjunctival involvement in 43%. The conjunctival changes were mostly “cobblestone” appearance of the papillae, with papillary reaction, and papillary hypertrophy whereas the lid showed isolated blepharitis, and loss of the eyelashes, and eczema of the eyelids. These changes had a male preponderance, and family history of atopy was seen to be a significant indicator for ocular changes.

Psychosocial aspects

The quality of life of the patient as well as of the family is often profoundly disturbed, which may lead to various grades of behavioral difficulties.[20]

Erythroderma/Generalised Exfoliative Dermatitis

Although erythroderma [Figure 7] rare, it may occur due to superinfection, and occasionally due to the withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids.[20]

Figure 7.

Atopic dermatitis: Erythoderma depicted dry red and scaly skin

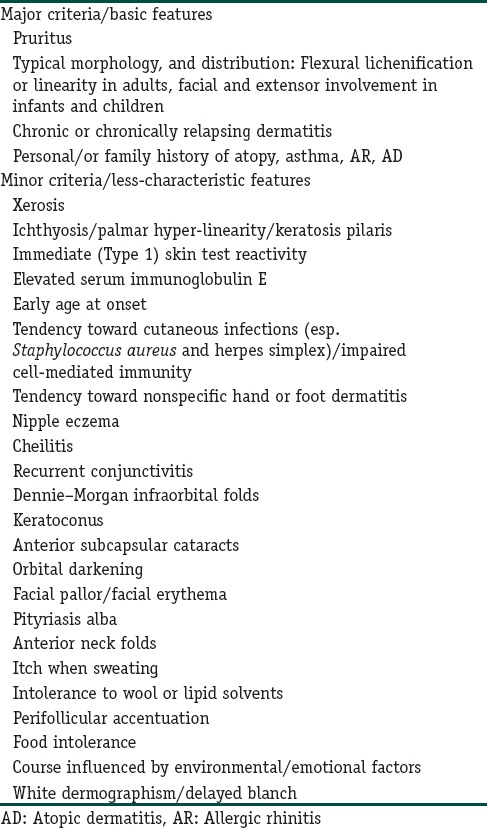

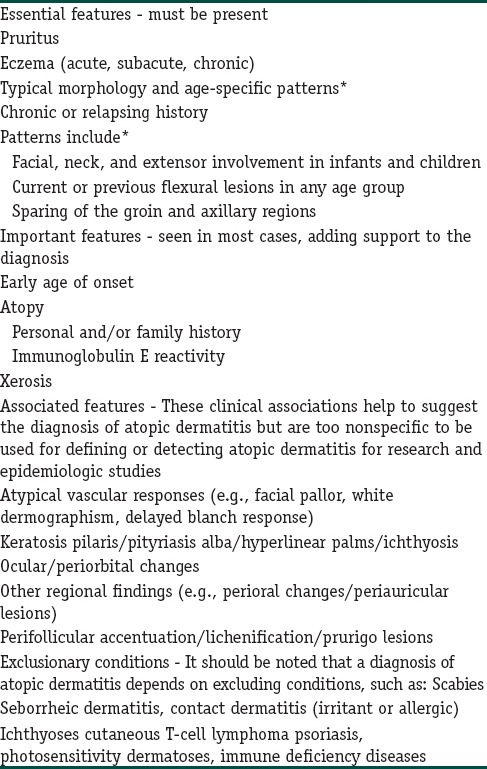

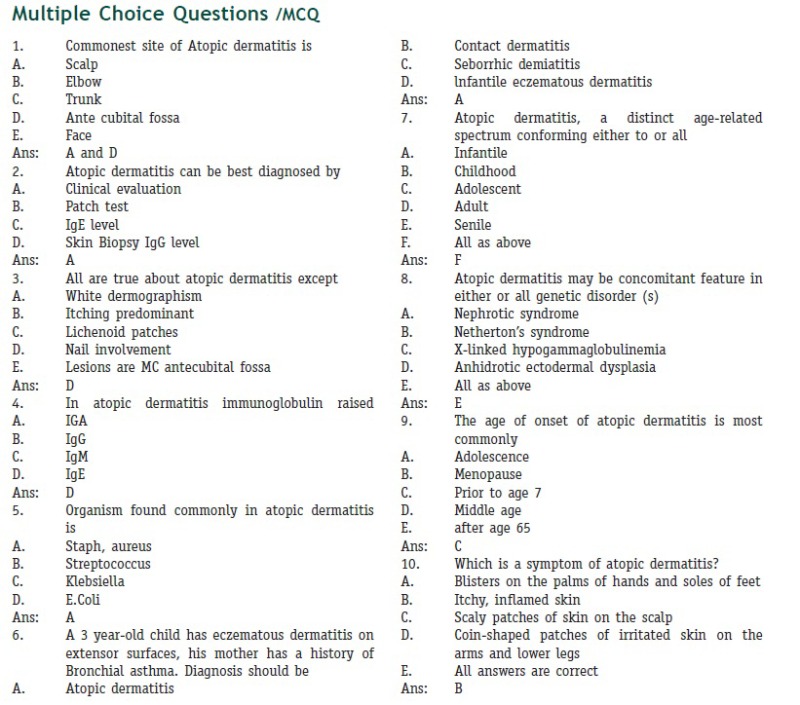

Diagnosis: Changing Scenario

Hanifin and Rajka[4] pioneered a systematic approach towards the standardization of the diagnosis of AD and proposed four major and 23 minor criteria, of which presence of three major and three minor criteria could be diagnostic [Table 2]. Despite a certain reservation, these criteria have remained a gold standard in research and academic teaching. The UK Working Party[23] criteria [Table 3] provides a validated instrument for epidemiologic studies. De et al. found statistical advantage in favor of Hanifin and Rajka's criteria (sensitivity, 96.4%; specificity, 93.75%) compared with the UK Working Party's diagnostic criteria (sensitivity, 86.14%; specificity 95.83%).[23]

Table 2.

Atopic dermatitis: Hanifin and Rajka[3] criteria

Table 3.

Atopic dermatitis: UK Working Party criteria[23]

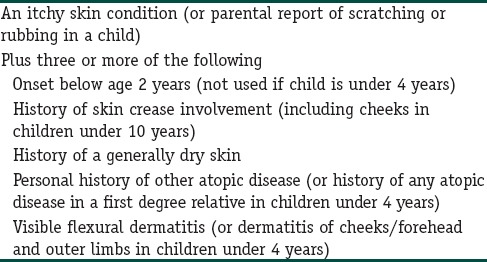

Williams et al.[14] coordinated a UK Working Party to attempt to refine the criteria of Hanifin and Rajka into a repeatable and validated set of diagnostic criteria for AD which is shown in Table 3.

A consensus conference on pediatric AD spearheaded by the American Academy of Dermatology[24] had suggested a revised Hanifin and Rajka[4] criteria [Table 4] that are more streamlined and additionally applicable to the full range of ages affected. While this set has not been assessed in validation studies, it is felt by the current work group that an adaptation of this pragmatic approach for diagnosing AD in infants, children, and adults is well suited for use in the clinical setting.

Table 4.

Atopic dermatitis: consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis spearheaded by the American Academy of Dermatology[24]

Laboratory studies[25] are rarely required to confirm the diagnosis of AD, which is primarily based on clinical features. Estimation of serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), prick tests, radioallergosorbent test (RASTS) may be undertaken which paradoxically can be negative in up to one fourth of atopics and may be positive in 15% of normal individuals.

Histopathology

In early phases, there is mild spongiosis, exocytosis of lymphocytes, and parakeratosis. Lymphocytes and scattered histiocytes are present around the superficial vascular plexus.

In long-standing lesions, the rete ridges are regularly elongated, with less prominent spongiosis and cellular infiltrate. Hyperkeratosis and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with areas of parakeratosis develop. There appear to be an increased number of small vessels with thickened walls. Eosinophils are less conspicuous than in allergic contact or nummular dermatitis.[25,26]

Differential Diagnosis

Several other conditions may stimulate AD. In an infant seborrheic dermatitis is the most common of these. Occasionally, it may be difficult to differentiate between these two, because of some overlapping features shared by them. Pruritus, age at onset and a family history of atopy cannot reliably discriminate between these two entities. Lesions over the forearms and shins and specific serum IgE to egg white and milk favor the diagnosis of AD. In the case of infantile seborrheic dermatitis, the lesions are often found in the seborrheic sites on the face, neck folds, axillae and/or the groin folds.[27]

Scabies in babies often undergoes eczematization, particularly over the face, quite closely simulating AD. A history of acute itching among the family contacts, the presence of burrows and inflammed papules and nodules over the genital and axillary areas support a diagnosis of scabies with eczematization.[28]

Other conditions which need to be considered are contact dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, impetigo, lichen simplex chronicus, nummular eczema, and psoriasis.[29]

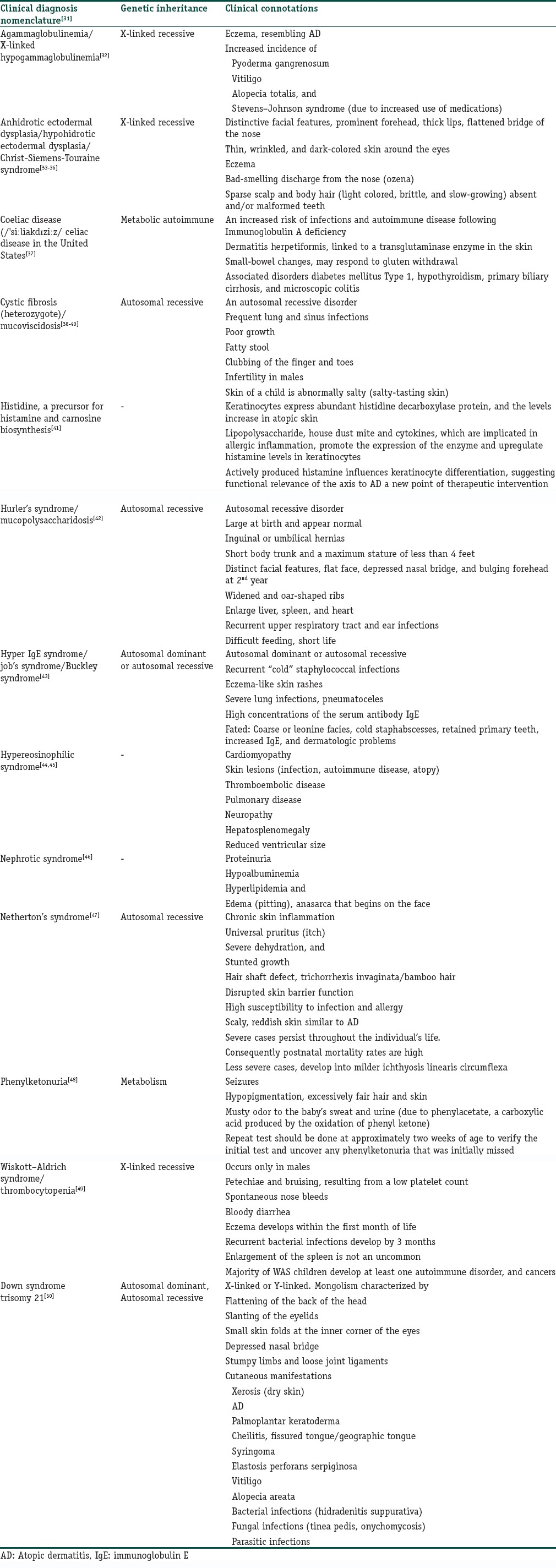

There are a number of genetic and metabolic disorders [Table 5][25] wherein an eruption resembling AD may develop (with or without other atopic disorders) or which are associated with a raised IgE level. Many such conditions are immuno-compromised states.[30] Thus, these conditions are to be suspected when a patient is having eczema-like AD, but is not responding to conventional treatment. It may also be a plausible facet to define its etiopathogenesis.[7]

Table 5.

Concomitant atopic undertones in genetic susceptibility and metabolic disorders

Associated dermatoses

A variety of dermatoses is associated, and may lead to increased severity of AD through exacerbations and stress. Infections, such as bacterial, fungal, and viral, are frequent and often become recurrent and chronic. Others such as alopecia areata, drug reactions, and pigmentary disorders[26] are often encountered.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

In addition to changing scenario of atopic dermatitis, a focus on concomitant atopic undertones in Immuno-compromised/susceptible genetic and metabolic disorders is formed to enlighten the audience in furthering their role in comprehension of its etio-pathogenesis.

References

- 1.Berke R, Singh A, Guralnick M. Atopic dermatitis: An overview. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunj B, Reng J. Clinical features and diagnostic criteria of atopic dermatitis. In: Herper J, Orasje A, Prose N, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology. 1st ed. London, England: Blackwell Science; 2000. pp. 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanifin JM. Atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudzki E, Samochocki Z, Rebandel P, Saciuk E, Galecki W, Raczka A, et al. Frequency and significance of the major and minor features of Hanifin and Rajka among patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1994;189:41–6. doi: 10.1159/000246781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eller E, Kjaer HF, Høst A, Andersen KE, Bindslev-Jensen C. Development of atopic dermatitis in the DARC birth cohort. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(2 Pt 1):307–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehgal VN, Khurana A, Mendiratta V, Saxena D, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK. Atopic dermatitis; etio-pathogenesis, an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:327–31. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.160474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, Saxena D, Chatterjee K, Khurana A. Atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional (Descriptive) study of 100 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:519. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.164412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of atopic dermatitis in a North Indian pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:347–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, editors. Dermatology. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanei R. Atopic dermatitis in the elderly. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;8:398–404. doi: 10.2174/1871528110908050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Dogra S. Atopic dermatitis: Current options and treatment plan. Skinmed. 2010;8:335–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mevorah B, Frenk E, Wietlisbach V, Carrel CF. Minor clinical features of atopic dermatitis. Evaluation of their diagnostic significance. Dermatologica. 1988;177:360–4. doi: 10.1159/000248607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. The U.K. Working Party's diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:406–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar R, Kanwar AJ. Clinico-epidemiological profile and factors affecting severity of atopic dermatitis in North Indian children. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhar S, Mandal B, Ghosh A. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of atopic dermatitis in 100 children seen in city hospital. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:202–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulig M, Bergmann R, Klettke U, Wahn V, Tacke U, Wahn U. Natural course of sensitization to food and inhalant allergens during the first 6 years of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:1173–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Hulst AE, Klip H, Brand PL. Risk of developing asthma in young children with atopic eczema: A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:565–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spergel JM. From atopic dermatitis to asthma: The atopic march. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung DY, Eichenfield LF, Boguniewicz M. Atopic dermatitis (atopic eczema) In: Freeberg IM, Eausten KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2003. pp. 1180–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palit A, Handa S, Bhalla AK, Kumar B. A mixed longitudinal study of physical growth in children with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:171–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.32740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaujalgi R, Handa S, Jain A, Kanwar AJ. Ocular abnormalities in atopic dermatitis in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:148–51. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.48659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De D, Kanwar AJ, Handa S. Comparative efficacy of Hanifin and Rajka's criteria and the UK Working Party's diagnostic criteria in diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in a hospital setting in North India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:853–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eichenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Luger TA, Stevens SR, Pride HB. Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1088–95. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung DY, Nicklas RA, Li JT, Bernstein IL, Blessing-Moore J, Boguniewicz M, et al. Disease management of atopic dermatitis: An updated practice parameter. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(3 Suppl 2):S1–21. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu H, Heather AB, Terence JH. Non vesiculobullous and vesiculopustular diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnsin BL, Murphy GF, Xu X, editors. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 240–1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhar S, Banerjee R. Atopic dermatitis in infants and children in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:504–13. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.69066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung DY, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:151–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James WD, Berger TG, Elston . University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, Romano C. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in patients with Down syndrome: A clinical survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 Pt 1):1019–21. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung DY, Eichenfield LF, Boguniewicz M. Atopic dermatitis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrst BA, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. Kansas: McGraw Hill; 2012. pp. 165–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lankisch P, Laws HJ, Weiss M, Borkhardt A. Agammaglobulinemia and lack of immunization protection in exudative atopic dermatitis. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:117–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James W, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koguchi-Yoshioka H, Wataya-Kaneda M, Yutani M, Murota H, Nakano H, Sawamura D, et al. Atopic diathesis in hypohidrotic/anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:476–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sehgal VN, Sehgal N, Sehgal R, Bajaj P, Kumar S, Kapur R. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: Evaluation through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) J Dermatol. 2002;29:606–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matos J, Ornellas L, Carvalho B. 544 clinical features of patients with ataxia-telangiectasia at reference center in Sao Paulo, Brazil. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5(Suppl 2):S189–90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ress K, Annus T, Putnik U, Luts K, Uibo R, Uibo O. Celiac disease in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:483–8. doi: 10.1111/pde.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson LA, Callerame ML, Schwartz RH. Aspergillosis and atopy in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:863–73. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinton PM. Cystic fibrosis: Lessons from the sweat gland. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:212–25. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckingham L. Molecular Diagnostics Fundamentals, Methods, and Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co; 2012. p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutowska-Owsiak D, Greenwald L, Watson C, Selvakumar TA, Wang X, Ogg GS. The histamine-synthesizing enzyme histidine decarboxylase is upregulated by keratinocytes in atopic skin. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:771–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banikazemi M. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I at eMedicine. Updated. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohameje NU, Loveless JW, Saini SS. Atopic dermatitis or hyper-IgE syndrome? Allergy Asthma Proc. 2006;27:289–91. doi: 10.2500/aap.2006.27.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Longmore M, Wilkinson I, Turmezei T, Cheung CK. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford: Oxford; 2007. p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leonardi S, Filippelli M, Costanzo V, Rotolo N, La Rosa M. Atopic dermatitis, short stature, skeletal malformations, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, hypereosinophilia and recurrent infections: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:253. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei CC, Tsai JD, Lin CL, Shen TC, Li TC, Chung CJ. Increased risk of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:2157–63. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hannula-Jouppi K, Laasanen SL, Heikkilä H, Tuomiranta M, Tuomi ML, Hilvo S, et al. IgE allergen component-based profiling and atopic manifestations in patients with Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:985–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vickers CF. Eczema and phenylketonuria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1964;50:56–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan KE, Mullen CA, Blaese RM, Winkelstein JA. A multiinstitutional survey of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J Pediatr. 1994;125(6 Pt 1):876–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, Romano C. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in patients with Down syndrome: A clinical survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 Pt 1):1019–21. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]