Abstract

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic granulomatous infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by specific group of dematiaceous fungi. The infection results from traumatic injury and is seen more commonly on feet and lower legs. It is rarely seen in children and metastatic spread to other systems is exceptionally rare. We report a 12-year-old immunocompetent male child diagnosed with chromoblastomycosis on the lower leg, who in a span of few months developed osteomyelitis and left hemiparesis. Fungal culture showed growth of Exophiala spinifera. Child showed good improvement with voriconazole and itraconazole after 1 year of treatment. Skin lesions healed with minimal scarring and his power improved.

Keywords: Chromoblastomycosis, Exophiala spinifera, fungal granuloma, fungal osteomyelitis, voriconazole

What was known?

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic granulomatous infection caused by dematiaceous fungi. Systemic involvement is rarely manifested and reported in literature.

Introduction

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic subcutaneous infection caused by several pigmented fungi such as Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, and other species. Among them, the most common etiological agent is Fonsecaea pedrosoi.[1] Other rarely reported agents include Exophiala spinifera and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa.[2] E. spinifera belongs to family Herpotrichiellaceae in the fungal order Chaetothyriales. It is a well-recognized etiological agent of phaeohyphomycosis and has been described as causing chromoblastomycosis in few cases.[2,3] We describe the first case of chromoblastomycosis in a child with metastatic spread to bone and central nervous system caused by E. spinifera in an Indian scenario.

Case Report

A 12-year-old school going male child, son of an agriculturist was referred from Pediatric Neurology Department for evaluation of slowly progressive, asymptomatic skin lesions on the dorsum of the left foot since 1 year and progressive weakness of left upper and lower limbs since 6 months. There was no history of discharge from the lesions or trauma preceding the onset of skin lesions. He was diagnosed with deep fungal infection before presenting to us and started on oral terbinafine. The child had taken treatment for 1 month but stopped abruptly. After 6 months of onset of skin lesions, the child developed painful swelling of the left elbow joint and weakness of left upper and lower limbs. Personal and family history was nonsignificant.

General physical examination showed wasting of left upper and lower limbs. His gait was altered with difficulty in walking. Vitals were normal. Cutaneous examination showed well to ill-defined hyperkeratotic, verrucous plaque measuring 6 cm × 4 cm surrounded by hyperpigmented area on the dorsum of left foot [Figure 1a]. Ill-defined swelling measuring 3 cm × 4 cm with an overlying scaly plaque was present on the left elbow joint extending to proximal part of left forearm [Figure 1b]. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Neurological examination revealed left upper and lower limb power 3/5 (Medical Research Council [MRC] Grade). On investigations, hemoglobin was 12.8 g% with normal total and differential leukocyte count. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (70 mm/h). Blood biochemistry, urine examination, blood sugar, and chest X-ray were normal. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) levels (IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE) were within normal limits. Serology for syphilis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human immunodeficiency virus were negative. CD3/CD4/CD8 absolute counts by flow cytometry done were normal. Nitro blue tetrazolium test for phagocyte dysfunction was also normal. Portion of skin tissue taken, crushed, and mounted in 10% KOH showed pigmented sclerotic bodies [Figure 2a]. Skin biopsy from the verrucous plaque on the left foot revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; dense infiltrate of plasma cells, macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and giant cells in the dermis. There were numerous pigmented round bodies called sclerotic bodies (copper penny bodies) within the giant cells [Figure 2b]. Histopathological examination of curettage of the lytic lesion from upper third radius showed sheets of histiocytic cells, giant cells, sclerotic bodies, and septate elongated fungi within the giant cells indicative of fungal osteomyelitis [Figure 3a and b]. X-ray of left elbow joint showed expansile osteolytic lesion on the proximal end of left radius [Figure 4]. Mantoux test was negative. Skin biopsy culture in Sabouraud's dextrose agar grew yeast like, moist, pigmented colonies after 5–7 days of incubation at 28–30°C [Figure 5a]. The isolate was referred to National Culture Collection of Pathogenic Fungi, Department of Microbiology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Centre, Chandigarh for further identification (fungal isolate deposit identification IL-K491). The isolate was identified and confirmed as E. spinifera [Figure 5b]. Molecular identification was performed by sequencing internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region or rDNA. NCBI BLAST results showed 99% identity with the E. spinifera strain CNRMA9.192 isolate ISHAM-ITS_IDMITS1660. MRI of the brain showed rim enhancing lesions in bilateral frontal lobes with peripheral sunburst pattern surrounded by rim of hypointensity producing a “double ring sign” suggestive of fungal granuloma [Figure 6]. Based on the above findings, a diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis with bone and central nervous involvement was considered.

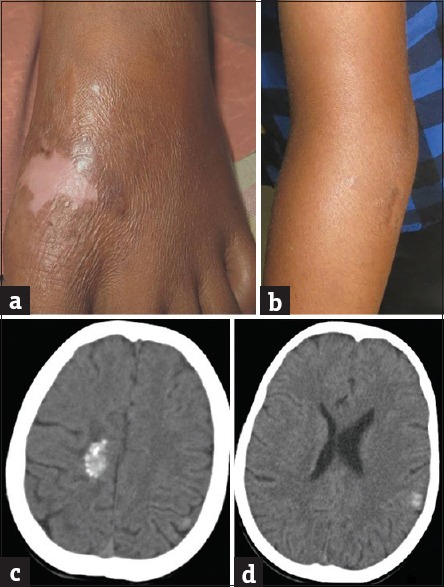

Figure 1.

(a) Well to ill-defined hyperkeratotic, verrucous plaque surrounded by hyperpigmentation on the dorsum of the left foot. (b) Ill-defined swelling with overlying scaly plaque on the proximal part of left forearm

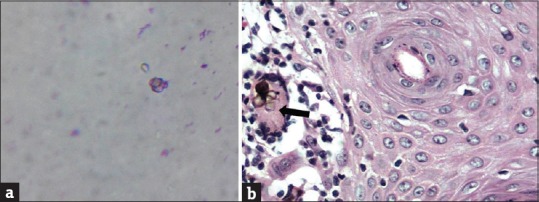

Figure 2.

(a) KOH smear showing pale brown sclerotic bodies. (b) Brownish pigmented sclerotic bodies in giant cell (H and E, ×40)

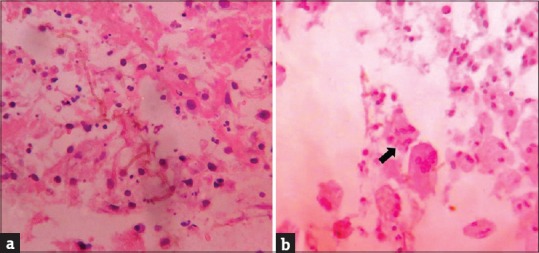

Figure 3.

(a) Septate elongated fungi in the necrotic tissue in bone tissue. (b) Fragmented fungi present in giant cell in bone tissue (H and E, ×40)

Figure 4.

X-ray of left elbow and forearm bones (anterior-posterior view) showing multiple destructive lytic lesions with periosteal reaction and soft tissue swelling at the proximal end of the radius

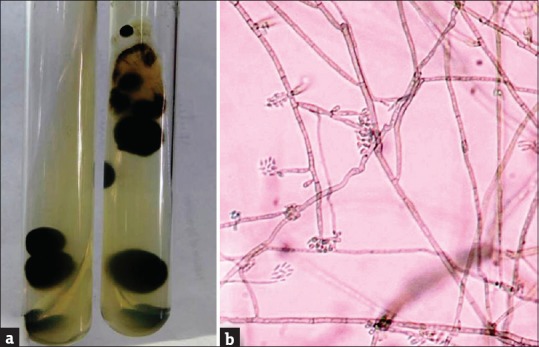

Figure 5.

(a) Macroscopic appearance of culture showing yeast like, moist, pigmented colonies. (b) Slide culture showing stout, spine like conidiophores with snout like tips and one cell conidia indicative of Exophiala spinifera (Lactophenol cotton blue × 40)

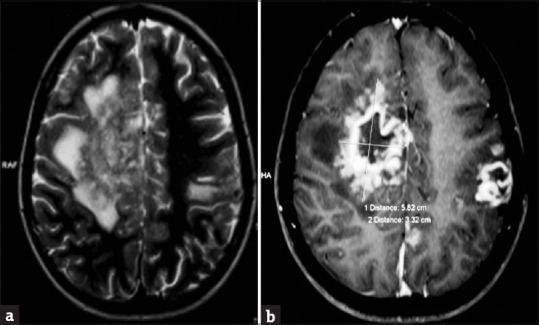

Figure 6.

(a) Axial T2 and flair image demonstrating an iso- to hypointense mass lesion in the right frontal lobe with a peripheral sun burst pattern and perilesional edema. Left frontparietal hyperintensity is also noted. (b) Axial T1-weighted image revealing rim enhancing lesions in bilateral frontal lobes with sunburst/gyral pattern in the periphery surrounded by a rim of hypointensity producing a “double ring sign”

The child was started on intravenous voriconazole 6 mg/kg body weight twice/day on day1 and maintained on 4 mg/kg body weight twice/day for 10 days. After 10 days, the child was started on oral voriconazole 100 mg twice/day and itraconazole 100 mg twice/day for 3 months. Due to the cost constraint, voriconazole could not be continued. Child was further continued on itraconazole for 6 months along with physiotherapy with good clinical improvement. Itraconazole was continued for 1 year. Skin lesions resolved with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation [Figure 7a]. Skin lesion along with swelling of the left elbow joint reduced [Figure 7b]. There was a reduction in the size of the soft tissue swelling and lytic lesions. His power improved to 4/5 (MRC Grade). Repeat computed tomography scan of the brain after 8 months showed complete resolution of lesion with calcification [Figure 7c and d]. Child was under follow-up with us regularly for 1 year.

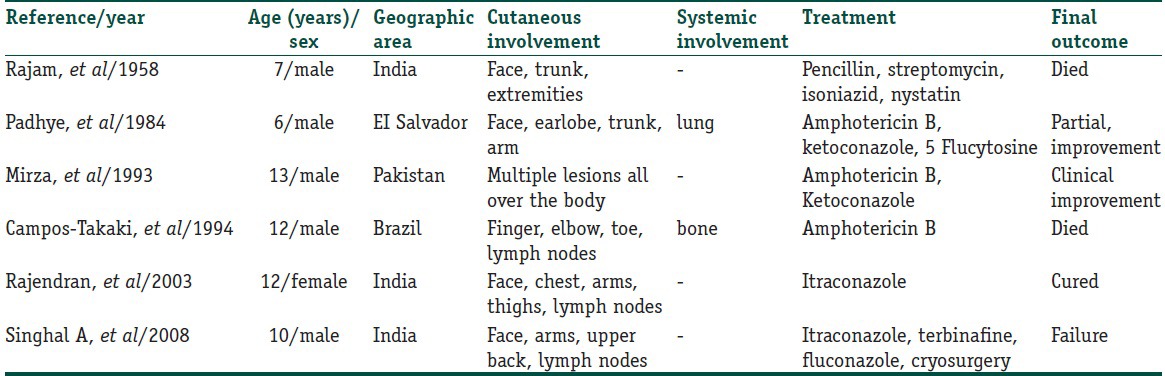

Figure 7.

(a) Skin lesion on dorsum of feet resolved with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. (b) Scaly plaque along with swelling of the left elbow joint reduced. (c and d) Repeat computed tomography scan of brain showing calcification in right parasagital and left parietal lobe with complete resolution of perilesional edema

Discussion

Chromoblastomycosis occurs throughout the world but is more common in tropical and subtropical regions with Madagascar and Brazil having largest reported cases.[1,4] It affects rural workers, especially those coming from endemic region. Many cases have been published in literature from different parts of India that includes Assam, sub-Himalayan belt, western and eastern coasts, Bihar, Jammu and Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Puducherry.[1] Chromoblastomycosis has a predilection for men between the age group of 30 and 50 years. It is rarely seen in children.[1,5] Pérez-Blanco et al. described 22 cases of chromoblastomycosis in children and adolescents in an endemic area of the Falcon State, Venezuela. Among the 22 cases, the youngest age seen was 2 years and was seen more in male children.[6] The higher incidence of chromoblastomycosis in males in their study was probably attributed to the result of their early work as goat herders and to their outdoor recreational activities that would bring them in contact with the natural vegetative reservoir of the etiologic agent in the endemic area.[6] 54.55% children had close relatives who had chromoblastomycosis suggesting a familial predisposition.

Literature review has shown that there is 47–65% risk of inheritable susceptibility to chromoblastomycosis, supporting that genetic factor may play an important role in the development of the disease.[6,7] Studies have shown that the susceptibility to chromoblastomycosis may be influenced by a gene located on chromosome 6, in the region of major histocompatibility complex suggesting that individuals carrying human leukocyte antigen-A 29 have a 10-fold increased risk of developing the disease than those lacking the antigen.[6] More research must be done in this aspect.

Clinically, the lesions present in five different types: Nodular, tumoral lesions, verrucous, plaque and cicatricial. It begins slowly over months to years starting initially as a warty papule to hyperkeratotic, verrucous plaque which may be localized or multiple lesions can be present associated with satellite lesions. It can also present as ulcerative or sporotrichoid form. It heals with central atrophy and scarring. Most common sites involved are trauma-prone areas and rarely trunk and face.[8] Spread to contiguous sites may occur through lymphatic extension and hematogenous route. Metastatic spread to other organs like lung and bone have been reported but clearly represents a minority of cases.[9]

Diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis is based on KOH examination of skin tissue, aspirated material for the presence of septate hyphae and sclerotic bodies. The hallmark of the disease is the presence of dark brown, thick-walled spherical bodies, 5–15μm in diameter, with thick, planate septal walls called sclerotic bodies (copper pennies, medlar bodies).[5,6] E. spinifera has been reported to cause both pheohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. The clinical spectrum ranges from cutaneous/subcutaneous lesions to life-threatening disseminated infections.

Pheohyphomycosis caused by E. spinifera is rare, and only 6 cases have been reported in pediatric age group in English literature. Among the 6 cases reported, 4 cases had disseminated cutaneous involvement, and 2 cases had disseminated cutaneous with systemic involvement [Table 1].[10,11,12,13] E. spinifera causing central nervous involvement has not been reported in this age group. Chromoblastomycosis has to be differentiated clinically from other infectious disorders such as cutaneous tuberculosis, leprosy, tertiary syphilis, nocardiosis, sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and leishmaniasis. Histopathological differential diagnosis includes all granulomatous conditions mentioned above along with sarcoidosis.

Table 1.

There are no definitive guidelines about the choice or duration of treatment of antifungals. Oral terbinafine and itraconazole for prolonged periods (6–12 months) have shown good results. In vitro studies have shown E. spinifera to be highly susceptible to itraconazole, voriconazole and posaconazole. Many studies have shown fluconazole and amophotericin B to be ineffective. Potassium iodide is also effective in chromoblastomycosis. Voriconazole has been reported to alter the natural rapid progression of the disease in pediatric patients.[14]

The present case represents the first case of pediatric chromoblastomycosis caused by E. spinifera. The unique feature noted in our case was that, in spite of the child being immunocompetent, he developed osteomyelitis and cerebral involvement. This could be explained due to the osteotropic and neurotropic nature of the fungus.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Chromoblastomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera with bone and central nervous involvement in a child is a rare occurrence seen in our patient.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Nailini Janakiraman, Professor and Head of Department of Microbiology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bangalore, Dr. Shivaprakash, Additional Professor, Mycology Division and Sunitha Gupta, Senior Medical Technologist, Centre of Advance Research in Medical mycology and WHO collaborating centre, Department of Medical Microbiology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Centre, Chandigarh for identification of the culture isolate. Dr. Lakshmi D.V, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Chandran V, Sadanandan SM, Sobhanakumari K. Chromoblastomycosis in Kerala, India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:728–33. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.102366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomson N, Abdullah A, Maheshwari MB. Chromomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:239–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padhye AA, Hampton AA, Hampton MT, Hutton NW, Prevost-Smith E, Davis MS. Chromoblastomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:331–5. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pires CA, Xavier MB, Quaresma JA, Macedo GM, Sousa BR, Brito AC. Clinical, epidemiological and mycological report on 65 patients from the Eastern Amazon region with chromoblastomycosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:555–60. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma GK, Verma S, Singh G, Shanker V, Tegta GR, Minhas S, et al. A case of extensive chromoblastomycosis from North India. Braz J Microbiol. 2014;45:275–7. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822014005000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-Blanco M, Hernández Valles R, García-Humbría L, Yegres F. Chromoblastomycosis in children and adolescents in the endemic area of the Falcón State, Venezuela. Med Mycol. 2006;44:467–71. doi: 10.1080/13693780500543238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naranjo F, Vilera L, Arrese-Igor N, Richard Yegres N, Yegres F, Chrino H, et al. Chromomycosis for Cladophialophora carrionii genetic component study in Venezuela endemic zone. Bol Soc Venez Microbiol. 1998;18:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panicker NK, Chandanwale SS, Sharma YK, Chaudhari US, Mehta GV. Chromoblastomycosis: Report of two cases on face from urban industrial area. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:371–3. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.120652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Guzman L, Perlman DC, Hubbard CE. Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis due to the chromoblastomycosis agent Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012;41:328–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris JE, Sutton DA, Rubin A, Wickes B, De Hoog GS, Kovarik C. Exophiala spinifera as a cause of cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis: Case study and review of the literature. Med Mycol. 2009;47:87–93. doi: 10.1080/13693780802412611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padhye AA, Ajello L, Chandler FW, Banos JE, Hernandez-Perez E, Llerena J, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis in El Salvador caused by Exophiala spinifera. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:799–803. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajendran C, Khaitan BK, Mittal R, Ramam M, Bhardwaj M, Datta KK. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera in India. Med Mycol. 2003;41:437–41. doi: 10.1080/1369378031000153820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singal A, Pandhi D, Bhattacharya SN, Das S, Aggarwal S, Mishra K. Pheohyphomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera: A rare occurrence. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:44–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trinh JV, Steinbach WJ, Schell WA, Kurtzberg J, Giles SS, Perfect JR. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis in an immunodeficient child treated medically with combination antifungal therapy. Med Mycol. 2003;41:339–45. doi: 10.1080/369378031000137369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]