Abstract

Sigmoid volvulus is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition that is usually seen in adults, however, when diagnosed in children, it is often associated with Hirschsprung's disease (HD). We report a case of an 11-year-old boy who presented with a history of constipation since 1.5 months of age, with acute onset of severe abdominal pain and marked distention of the abdomen. Sigmoid volvulus was suspected, detected and successfully managed with resection of the sigmoid colon and primary Scott Boley's pull-through. This report underscores the importance of suspecting sigmoid volvulus in the pertinent clinical setting; also, a primary definitive procedure can be performed in select cases.

Background

Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) is a relatively common cause of intestinal obstruction in the newborn.1 While HD is usually diagnosed during the neonatal period in developed countries, the diagnosis is often delayed in developing countries such as ours.2 Thus many children who present to us have an acutely dilated sigmoid colon that may twist if the base of the mesentery is narrow. Sigmoid volvulus (SV) is a rare, life-threatening complication of HD and has been reported in all age groups.3 Urgent intervention is always required to prevent life-threatening consequences. We report a case of a boy presenting with SV who, on evaluation, was found to have HD and offered primary single-stage definitive treatment.

Case presentation

An 11-year-old boy presented to us with a history of constipation associated with recurrent abdominal distension since 1.5 months of age. The patient had been managed on intermittent rectal enemas prior to presenting to us. His parents were unable to provide a history regarding passage of meconium. On examination, the child had stable vitals. Per abdominal examination revealed distension of the abdomen. The anus was normally located and of normal calibre. The rectum was collapsed on examination with a gush of gas and stools on withdrawing the finger. As the initial investigations (anorectal manometry and barium enema) were suggestive of HD, the child was started on rectal washouts and a rectal biopsy was planned.

The patient presented to us again after 2 weeks, with progressive abdominal distension that did not decompress even after rectal wash-outs and non-bilious vomiting. On examination, the child was dehydrated and had tachycardia. The abdomen was grossly distended with a palpable dilated bowel loop. The abdomen was tense but guarding and rigidity were absent. Per rectal examination revealed an empty rectum with passage of neither gas nor faeces on withdrawing the finger.

Investigations

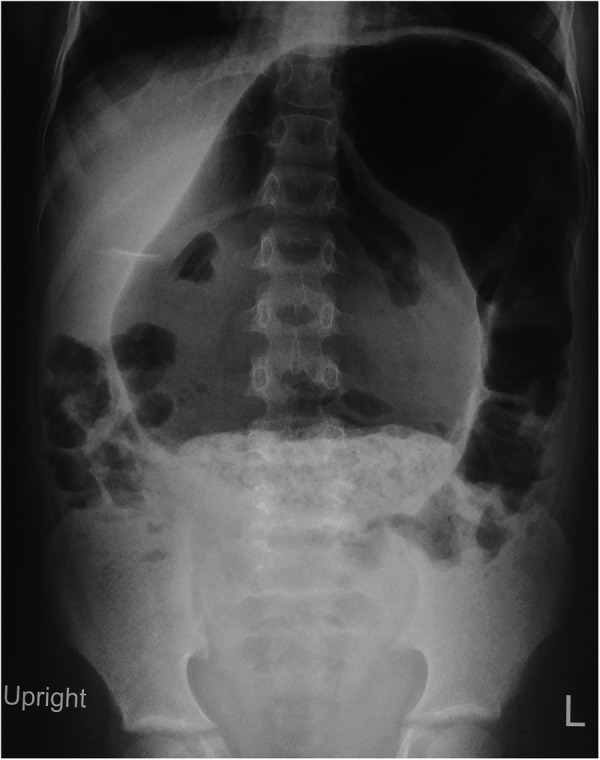

Anorectal manometry and barium enema were performed at the time of initial presentation. The anorectal manometry showed absence of anorectal reflex. The barium enema revealed a dilated sigmoid colon with transition zone at the rectosigmoid junction (figure 1). A plain abdominal radiograph (figure 2), performed when the child presented to us with acute symptoms, was suggestive of a hugely dilated loop of colon with a coffee bean appearance and absent rectal gas.

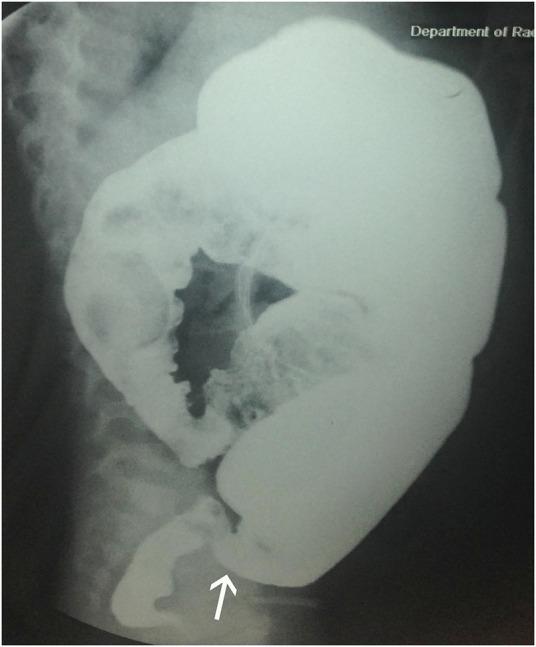

Figure 1.

Lateral view of the barium enema shows collapsed rectum and dilated sigmoid colon with inversion of the rectosigmoid ratio. Transition zone is seen at the rectosigmoid junction (white arrow).

Figure 2.

Plain erect radiograph of the abdomen showing a large inverted U-shaped dilated bowel loop arising from the pelvis.

Treatment

The child was stabilised with fluid resuscitation and gastric decompression. Preoperative electrolytes were normal. He underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed presence of a viable redundant loop of sigmoid that had rotated on its mesentery (figure 3). Derotation of the SV was carried out with 1½ clockwise turns. The transition zone was present at the rectosigmoid junction and confirmed on frozen section. Resection of the dilated sigmoid colon and primary Soave pull through (Scott Boley's modification) were performed without a covering stoma.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photograph showing large dilated redundant sigmoid colon that is twisted around its base (black arrow).

Outcome and follow-up

The postoperative period was uneventful and the boy remained asymptomatic on follow-up.

Discussion

SV is a rare complication of HD, with a reported prevalence of 0.66%.4 Conversely, among children presenting with SV, 18% also have HD.4 Unrecognised SV can be life-threatening, so its possibility should be considered in children presenting with acute or recurrent abdominal pain, distension, constipation, nausea and vomiting.5 Early diagnosis of volvulus has been found to decrease morbidity and increase survival.6

SV occurs due to rotation of a redundant sigmoid loop around a narrow, elongated mesentery. HD with its transition zone at the rectosigmoid junction results in dilation and elongation of the sigmoid, which may predispose the child to develop volvulus of the sigmoid colon. The volvulus subsequently results in venous and arterial occlusion leading to haemorrhagic infarction, perforation, septic shock and death.7

The diagnosis of SV can often be determined from a good clinical examination and careful interpretation of plain abdominal radiographs. Radiographs show a markedly distended inverted U-shaped bowel loop with both the limbs directed towards the pelvis (coffee-bean sign).

The approach to SV in children remains controversial. Initial management of children with SV includes fluid resuscitation and antibiotics. Zeng et al8 reviewed the literature describing colonic volvulus secondary to HD in children and concluded that non-operative reduction of volvulus with contrast enema, or sigmoidoscopy or rectal tube placement is a viable option for clinically stable patients. If bowel gangrene or peritonitis is suspected, then the child should be operated on immediately after initial resuscitation. Successful non-operative reduction of the SV is feasible in 30–70% cases and the remaining cases with persistent volvulus warrant immediate surgery. Non-operative reduction alone carries a high recurrence rate (35%),6 therefore it is not the definitive treatment, but does allow stabilisation of the patient and preparation of the colon for surgery. Definitive treatment involves resection of the redundant sigmoid colon and anastomosis. HD is frequently associated with SV in children, so a rectal biopsy is recommended in all cases. If histopathological examination of the biopsy is suggestive of HD, then pull-through should be carried out after resection of the redundant sigmoid colon.

In the index case, the bowel was healthy and the descending colon was not overly dilated, therefore a single-stage procedure (Scott Boley's modification of endorectal pull-through) was performed after confirmation of transition zone and resection of the redundant sigmoid colon. In the past, these patients were managed in a staged manner after initial diversion with a colostomy.

In conclusion, SV is a rare complication of HD especially in children with a history of chronic constipation and delayed HD diagnosis. Owing to this condition is both uncommon, and challenging to diagnose and manage in children, a possibility of SV should be considered in these children. A high suspicion of SV in HD should be considered in clinical settings of recent onset gross abdominal distension and failure to decompress despite rectal washes.

Learning points.

Sigmoid volvulus is a rare condition in children and is often associated with Hirschsprung's disease.

Sigmoid volvulus needs urgent intervention to prevent bowel necrosis.

Primary definitive surgery can be performed if the bowel is healthy and expertise available.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Dasgupta R, Langer JC. Hirschsprung disease. Curr Probl Surg 2004;41:942–88. 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma S, Gupta DK. Hirschsprung's disease presenting beyond infancy: surgical options and postoperative outcome. Pediatr Surg Int 2012;28:5–8. 10.1007/s00383-011-3002-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erdener A, Ulman I, Ozcan C et al. A case of sigmoid volvulus secondary to Hirschsprung's disease. Pediatr Surg Int 1995;10:409–10. 10.1007/BF00182242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarioğlu A, Tanyel FC, Büyükpamukçu N et al. Colonic volvulus: a rare presentation of Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:117–18. 10.1016/S0022-3468(97)90113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seger DL, Middleton D. Childhood sigmoid volvulus. Ann Emerg Med 1984;13:133–5. 10.1016/S0196-0644(84)80578-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SD, Golladay ES, Wagner C et al. Sigmoid volvulus in childhood. South Med J 1990;83:778–81. 10.1097/00007611-199007000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilk PJ, Ross M, Leonidas J. Sigmoid volvulus in an 11-year-old girl Case report and literature review. Am J Dis Child 1974;127:400–2. 10.1001/archpedi.1974.02110220098014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng M, Amodio J, Schwarz S et al. Hirschsprung disease presenting as sigmoid volvulus: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:243–6. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]